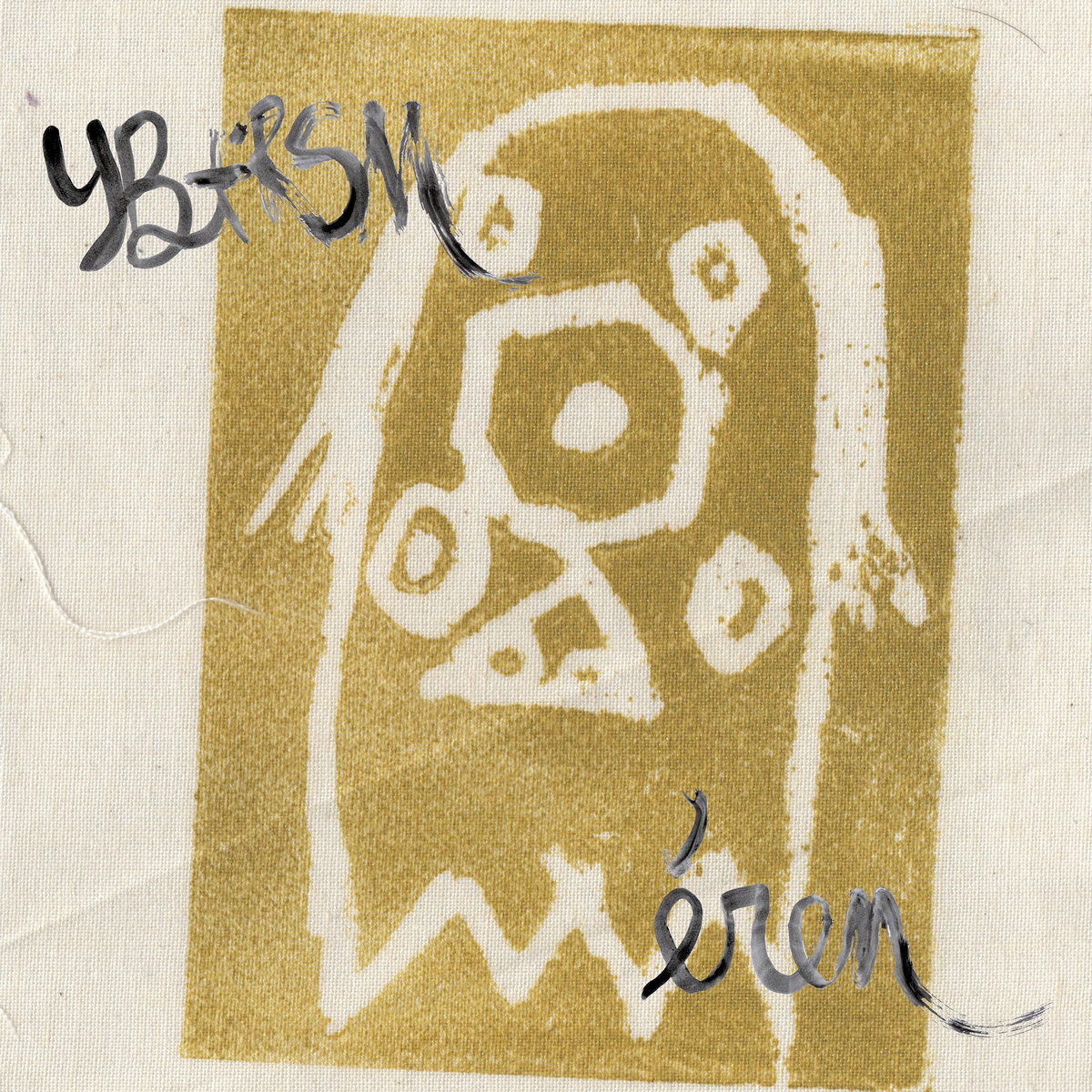

Yea Big and Ryan Scott Mattingly | Interview | New Album, ‘Iren’

Yea Big and Ryan Scott Mattingly’s new album ‘Iren’ is a work in progress, and a work about process. YB+RSM is the first album-length collaboration to be born from the FPE Records community.

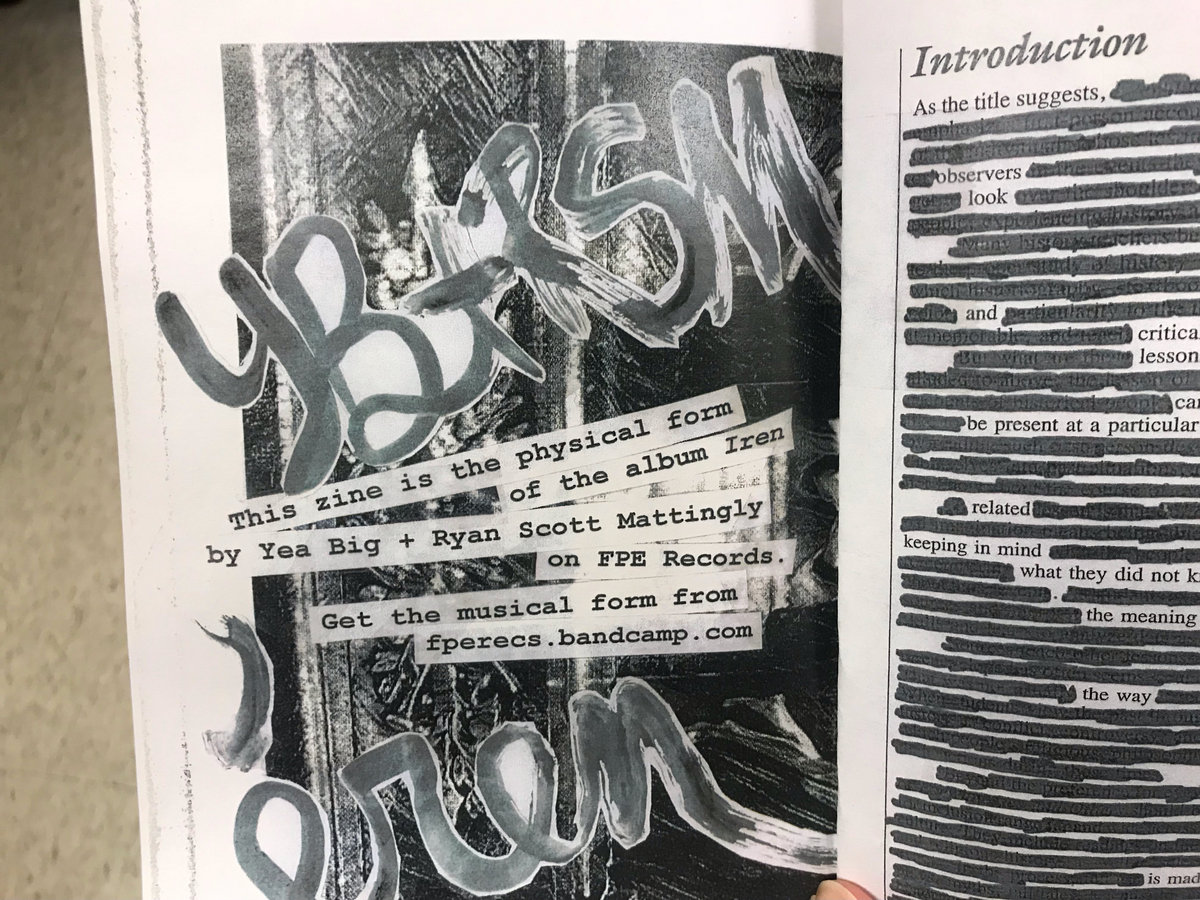

Stefen Robinson (Yea Big) got in touch with Ryan Scott Mattingly, half of the duo In Place, after hearing ‘Half Life,’ their dense, dark, claustrophobic 2020 release on FPE. A remote musical collaboration began between the Nashville, TN and Bloomington, IL-based artists, resulting in… noisy jazz. The ‘Iren’ in this sonic painting is the growth of Stefen’s and Ryan’s relationship. The unbroken motion between RSM and YB – the way their “strokes” flow back and forth – is just as important as what is physically audible in the recording. Just as a painting is both a work in itself and too the product of a choreography that occurs in time and space, so this thing is both a Pollock of pointillistic scuzz and an after-image imprinted in the digital space of hearts and minds growing together. ‘Iren’ is available digitally from FPE Records and it will also be available as a paper zine.

“One of the magical elements of making music with another person is the possibility of cultural diffusion”

What led to the project YB+RSM on FPE Records?

Stefen Robinson: I’ve been working with Matt Pakulski at FPE for a little while now. We have a somewhat long history, actually. I fell in love with Matt’s old band Fat Day many years ago while on tour with one of my main projects, Yea Big + Kid Static. We had some mutual friends who introduced us. We loosely kept in touch over the years. And then a couple of years ago when I was trying to decide how I wanted to release some of my future Yea Big projects I reached out to Matt, we talked quite a bit, we quickly realized we still had a mutual appreciation for each other’s art, an old friendship we wanted to rekindle, and very similar philosophies about art, so we began working together. I’m super grateful for Matt and his friendship.

Fast forward a bit, I picked up a cassette release from FPE by In Place, Ryan Scott Mattingly’s project with JayVe Montgomery, and I instantly fell in love with their work and their spirits. I very selfishly thought to myself, “I must make music with these guys,” so I reached out to Scott, and now here we are. Scott and I seem to be resonating on a similar plane of existence.

Ryan Scott Mattingly: I was grateful for Matt and FPE providing a home for In Place’s ‘Half Life’. Matt has legitimate bona fides in the outsider music world, so his name and label carry weight. When I listen to anything on FPE, I trust it’s going to be interesting, unique, clever and inspiring. Yea Big naturally fit that bill. After getting his letter, I jumped from record to record, clip to clip, video to video, feeling excited by the way that he moved from one idea to the next. Stefen is impossible to pin down or pigeonhole, and I admire that.

The process began with a long drum improvisation by Stefen. It had sections of capriciousness punctuating intense, focused patterns. I volleyed back some guitar, allowing myself the freedom to be silly. That juxtaposition of whimsy alongside serious jazz is something I was fascinated by when I was introduced to the Art Ensemble of Chicago. After working on a string of dirges, it felt childlike and joyful to play along. There is more smile and laughter in this album than any collaboration I’ve released.

What’s the concept behind ‘Iren’?

Stefen Robinson: “Iren” translates roughly to “continuous calligraphic motion” in the Japanese art of sumi-e painting. I was reading a book about sumi-e while Scott and I were working on this project and the way our ideas were flowing back and forth across time and space struck me as similar to the ways in which the fluid motions of a brush interact with paper. Our ideas, our sounds, our performances, the recording techniques, the mixing, et cetera are not the thing we’re sharing with each other and the world. What we’re sharing is the motion of it all.

Ryan Scott Mattingly: One of the magical elements of making music with another person is the possibility of cultural diffusion. Every individual involved brings in their affections, experiences and curiosities. Stefen’s interests were the catalyst for putting a name to what we were creating. I know very little about calligraphy or sumi-e, but every quote he sent me lined up with the approach we were taking to arranging these sounds.

Where was the album recorded and what can you tell us about the production?

Ryan Scott Mattingly: For my parts, I recorded at home using a variety of instruments. Most often, the electric guitar was my starting point. I worked in fits, taking 20 minutes here or there when it presented itself. I would record with a rotation of stompboxes and implements lying around. I expect an attentive ear could spot some of my common favorites: ebow, knitting needles, alligator clips, mallets, drumsticks, dulcimer hammers and screwdrivers. I recall synthesizer and dobro were employed liberally, and an unexpected MVP was the digital mellotron micro. I’m fond of how the instrument allows you to use a knob to blend the two mellotron sounds.

“Ideas would change and emerge fluidly”

Stefen Robinson: I recorded much of what I did at the high school I work at. I teach sociology and history, but I also help lead an “experimental” music ensemble at the school. And our school’s music department has been very generous with sharing space and resources with the ensemble and myself. Other things were recorded at home in my bedroom and laundry room. Everything we did was one take, and then the compositions would emerge more through the mixing process. Scott and I would record takes and send them back and forth. Ideas would change and emerge fluidly everytime one of us would add something.

Years ago when I interviewed Peter Brötzmann, I asked him what’s the difference between painting and making music and he replied: “[…] if you play music it’s out in the clouds and you can’t take it back and usually you do it together with at least one more person. Working in the studio (alone) on canvas or paper or whatever, you always can put the result into the garbage or stuff it into the oven and it never has existed. You start from the beginning.” What’s your thoughts on that?

Ryan Scott Mattingly: Brötzmann’s description is clearly evocative and beautiful but it’s situated on a subjective moon. His workflow reflects his time, location, and experience. Despite his music being a monolithic influence, my experience improvising, composing, performing and recording has differed greatly from his. For one, I don’t work the same way all the time. Sometimes what I play is completely improvised and stands recorded exactly as it was born. I admit that there’s something pure about that. I get why it is hailed as a gold standard among free players and jazz fans but there’s more than one path to the waterfall. ‘Bitches Brew,’ ‘In a Silent Way’ and ‘On the Corner’ would be very different if they followed that sort of blueprint. It reminds me of when I was in college and I was repeatedly told black-and-white maxims: like that a real guitarist should plug a guitar directly into an amp and be able to play anything or that a real song could be arranged to a solo acoustic guitar or piano. That’s bullshit. Whether Karlheinz Stockhausen, Glenn Branca, J Dilla, Harry Partch or Flying Lotus, there is a world of music that is authentic, thoughtful and “real” but that can’t be easily, neatly condensed in that way.

Stefen Robinson: I agree with what Scott said. I’m not I have much else to add. I will say, I love Brotzmann’s work. LOVE it. He’s been a heavy influence on my work. But I make music in many different ways. Further, making music as a performance and making music as a record are very different processes usually. I can easily stuff recordings, and often do, into the garbage just like a painting.

I would love it if you could talk a bit about your background. How did you first get interested in music?

Ryan Scott Mattingly: I grew up in a nowhere space. I should be clear that I had a great family but I was terribly alone, socially and emotionally. Without sounding too pretentious, I’ve always loved sound. It became an obsession as a little kid. My parents were divorced so I often had long cross-state drives occupying the hours with my Walkman. Once I heard ‘Smells like Teen Spirit,’ I was devoted to melancholy and the infinite feedback forevermore, wearing out cassettes by Smashing Pumpkins, Nine Inch Nails, Nirvana, and Radiohead… Each of those led to countless other loves: Nine Inch Nails introduced me to The Melvins, Badalamenti, Godspeed You! Black Emperor, Lou Reed, Bauhaus… Smashing Pumpkins led me to My Bloody Valentine, Joy Division, The Cure, David Bowie, The Jesus and Mary Chain… Nirvana begat my love for The Jesus Lizard, Sonic Youth, The Pixies, Daniel Johnston, Neil Young… Radiohead prepared me to lose my mind over Jeff Buckley, Sigur Ros, The Smiths, Steve Reich, Tom Waits… Then Tom Waits turned me to Captain Beefheart who leaned toward Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters then eventually I found myself at Alan Lomax, anthologies of folk music, field recordings, sound studies and international indigenous recordings. Those are the bones.

If I age bracketed it, I’d say childhood: Michael Jackson reigned before finding Nirvana and Metallica… adolescence: Smashing Pumpkins, Nine Inch Nails, Radiohead… late teens: Sigur Ros, Jeff Buckley, Bjork… young adulthood: Sonic Youth, Nels Cline then Marc Ribot and Tom Waits, then Naked City and Albert Ayler… I played along to CDs as a teen and learned what I could from a classical teacher at the community center. My guitar’s inability to hold tuning was likely the catalyst for me toying with what sounds it could make when I hit it with a pencil or wrapped aluminum foil around the strings. I enjoyed those experiments but I looked to college as the time I would really study hard and learn everything I could about guitar and making music. Unfortunately, I had a miserable experience trying to study guitar in college. I was left feeling much like I did when my guitar wouldn’t hold its tuning— creating music that I loved was something that I couldn’t really accomplish. I could fake it by playing what I felt and making up melodies and chord structures but it was destined to be puerile. The rejection by the musical authorities above me led me to the conclusion that I wasn’t ever going to be able to use guitar to make the art I wanted to. The sections of sound I loved in Radiohead or Miles Davis were created by geniuses and they were born with something I wasn’t. I stopped taking classes on music. I still played along to records every now and then in my dorm room, but I was resigned that it was a personal, isolated pursuit. At this low moment, I stumbled across Steve Reich’s essay on process music. This was an interesting path for me and I enjoyed creating simple repetitive structures. I never played them out on shows, but I daydreamed about finding a way to integrate the poetry I was writing with these musical patterns. That idea was in the back of my mind for many years and eventually I decided to try to study enough to have the skills to create the music I wanted to hear. Interventionist God somehow led me to stumble upon a guitar clinic with Duane Denison at just the right time. That helped some of the pieces fall into place because he has an incredible, mathematical understanding of music that he combines with this Stooges-esque swagger. Both of those sides resonated with me and set me on a hundred pathways. From there I studied a bit with Zoot Horn Rollo who kicked open doors of perception for me. He’s been learning and playing for an entire life, creating this ability to see connections between seemingly disparate concepts. Those two people really deserve great credit for helping me unearth the tools I used today.

Stefen Robinson: Music was always playing in my house as a kid. My mom was into Motown, so some of my earliest memories of falling in love with music have to do with the Temptations and Tops, Marvin Gaye, Aretha Franklin, Smokey Robinson, stuff like that. As Scott said, I too was always interested in sound, not just music. I started exploring making my own albums on a Tascam four-track recorder when I was in 8th or 9th grade. That was it. I’ve been doing the same thing, only now with a laptop, ever since. In 9th grade my musical world really exploded: I began a love affair with Fugazi, Coltrane and Dolphy, Phish, Ravi Shankar, Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman, Radiohead (that was probably 8th grade), et cetera. And then right around my senior year of high school I first heard Jim O’Rourke and his breadth of work really blew my mind. He confirmed my belief that I didn’t need to stick with any one thing. I could play mandolin in a bluegrass band, I could produce hip hop, I could make free improvised bass clarinet records, I could make sounds in any way that moved me. I’ve been seeking ways of making moving sounds most of my life.

“I want to create a vague, amorphous multiverse of sounds”

Stefen, what’s the idea behind the Yea Big project?

Stefen Robinson: “Yea Big” is a vague measurement. I’ve always resisted the notion that I needed to focus on one sort of music or another. I want to create a vague, amorphous multiverse of sounds, sometimes departing along different timelines, within which, if one is able to step back and see it in its entirety, would sonically tell a story about this fleeting existence. If people see the Yea Big moniker, they know it’s either me or me in collaboration, and they know they can expect something that is seeking. I’m always seeking. What I’m seeking is often a mystery. Haha!

Stefen, would you be willing to discuss some further words about the latest releases like ‘The Teeth Of My Thinking Machine’ and ‘An Emptiness Supreme Reimagined’?

Stefen Robinson: Well, as of this writing, I’ve released eight more projects since ‘The Teeth Of My Thinking Machine and I’m not quite sure where I’d begin. I make music somewhat obsessively, always working on multiple projects at a time. I don’t mean to be evasive, but all of my releases are somewhat different, and are best “discussed” by the sounds they produce, I think. But I’ll add, ‘The Teeth Of My Thinking Machine’ was super fun to make because I made it with a group of my students. ‘An Emptiness Supreme Reimagined’ was very special because a lot of friends recreated the original album in very exciting ways. Hopefully people will check out my other releases as well. Not everything is available everywhere, but most everything is on my Bandcamp page.

Ryan, tell us about the making of the 2020 album, ‘Orphan Work’? Would you say it’s a COVID album?

Ryan Scott Mattingly: The ‘Orphan Work’ title is a play on the musicology term but the songs are all original. They function as a cycle reflecting maligned and disinherited groups. It was heavily fueled by the preceding years of frustrating national policy, but there were inspirations more close-to-chest. I had moved away from my rural birthplace and was becoming aware of the physical and emotional distance between me and my relatives. It was a strange feeling to see my daughter cross milestones without my family around. There were some religious implications too as I came to the realization that God doesn’t intervene in our lives or reach down from heaven to stop evil and promote good. Sickness exists without a moral. I started writing the songs for my daughter when I was ill and doctors were having trouble figuring out a diagnosis. I integrated field recordings from our family life into the songs, wanting to document some of the emotions and passions that I hope she will carry on when I’m gone. It all has a happy ending as I’ve recovered and all is well. My daughter is actually hanging out beside me right now, reading a book about forest spirits. Unfortunately, ‘Orphan Work’ was released by Naviar Records a few weeks before the US declared the coronavirus a pandemic. It came into the world during February 2020, when anxiety was running high. To answer your question, ‘Orphan Work’ was not a pandemic record in the sense of addressing the pandemic, but my next record, ‘Half Life,’ was exactly that. During February and March 2020, I focused on my daughter and wife, trying to live as simply as we could. Nonetheless, I knew I had to find a healthy way to do something about the heavy, suffocating dread I felt was everywhere I turned. On April 1st, I woke before the rest of my family, went downstairs, set up one microphone and quietly recorded two improvisations. I decided I’d do that every day for April. After listening back to the first two, I sent them off to JayVe Montgomery with the idea that he might add something interesting. To my great surprise, he worked on each of these recordings with me. By May, I was sorting through hundreds of improvised takes, co-creating what became In Place with JayVe. FPE was incredibly supportive, helping us get this into people’s hands and minds in December 2020. It’s a dark record, but I think of it fondly. Those were dark days for most people and it reflects the times.

What’s next for you?

Ryan Scott Mattingly: In this weird dream life I’ve been living for the last couple years, I play in a handful of incredible bands in Nashville’s outsider music scene. In Place, my free improvisation band with JayVe Montgomery, Randy Hunt and John Westberry, is homebase for me. We have a show at the Blue Room at Third Man Records in a few weeks and I’m cooking up something fresh with a tabletop guitar with a false bridge a la Fred Frith. I’m always changing up the tools and equipment I use with that band. It keeps me from falling into the tropes or leaning on cliches. If I use a screwdriver at one gig, I’ll bring a mallet to the next and a drill to the one that follows that. If I use a bright fuzz at one show then the next one I’ll sub in a wooly distortion or a ring modulator. The guitar may be an archtop one time, Jazzmaster the next, Stratotone after that. It’s a good way to keep me focused on listening to what is happening around me instead of getting too comfortable. As for other things, this week I’m finishing tracking electric guitars for the Kyle Hamlett Cinco and going into the studio tomorrow to listen to some mixes with Altered Statesman. I have also been stealing moments here and there to add overdubs to a great record Gray Worry is making and working on a collaboration with the fantastic, fantastical sci-fi poet Dan Hoy.

Stefen Robinson: Artistically, I would love to keep collaborating with amazing people like Scott, making new sounds together. Hopefully one day Scott and I do a sequel! Personally, I’m going to keep doing my best to make this world a more loving and peaceful place. I suppose those things are actually one and the same though.

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

Ryan Scott Mattingly: I am infinitely curious, listening omnivorously, absorbing everything I can. I’m sure that osmosis means I’m pulling from the Abba ‘Greatest Hits’ playing at the deli I went to with my daughter for lunch, that Nas CD in the car, the Penderecki I had on in the kitchen yesterday. It’s all one river to me. As for standout moments, the first time I heard Marc Ribot was a spiritual awakening. It was the first time that I had heard someone playing what I wanted to play, but turning it and inverting it in ways I couldn’t imagine. I was nineteen or twenty and those first four tunes on ‘Rain Dogs’ wrecked me. I could praise each player but Ribot was the focal point since he was doing what I had given up on and cordoned off in my mind as impossible. There’s so much I love in what Ribot does: the musical deja vu he conjures when he impishly chews up melodies and spits them out in new forms that are slightly familiar yet altogether new, his awareness and embrace of how music is inherently political, the way he supports the themes of a song while using his space to deepen the discourse. Nels Cline is also great at this. He introduces sounds, notes and rhythms that fit the mood yet elevate the conversation. Not to group them together since there are infinite differences in their styles, but I’ve taken clinics with both of those guys and there’s an element of personality that comes through even when they’re warming up or playing something simple. That sense of individual voice was important to me since childhood, before I even understood how to verbalize that desire. Another thing that makes me tout their influence before Mingus, Alice Coltrane, Monk, Sun Ra, who are all huge in my world, is that Ribot and Cline both dance in many gowns. I enjoy playing with rock bands, songwriters, jazz quartets and Nashville Ambient Ensemble. If it’s good and my parts can add to the message of that music, I don’t care what labels it gets. Let other people call it avant garde or mainstream; I just want to be in service of the sound, listening and thoughtfully offering up what I can.

Stefen Robinson: I suppose I’m most influenced by peoples’ spirits, not their “playing,” per se. My biggest musical influences are probably Coltrane, Milford Graves, Radiohead, Fugazi, Jim O’Rourke, the others I mentioned above. The records that changed my life include, In A Silent Way, O’Rourke’s Eureka and Bad Timing, A Love Supreme, Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots by The Flaming Lips, I could go on and on.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Stefen Robinson: Thanks for this! It really means a lot to have someone like you interested in our work and be willing to help us share it with the world. You are appreciated, my friend!

Klemen Breznikar

Yea Big Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp

Ryan Scott Mattingly Facebook / Instagram / SoundCloud / YouTube

FPE Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube