Dominique Grimaud | Camizole | Vidéo-Aventures | Interview

Dominique Grimaud is a French multi-instrumentalist and sound experimentalist active since the early 1970s.

Dominique Grimaud started his musical activities in 1970 with an improvisation and happening group formed by Jacky Dupéty. The group performed under the name Camizole until 1978. In that year, it merged with another group called Lard Free. Later on he formed Video-Aventures with Monique Alba.

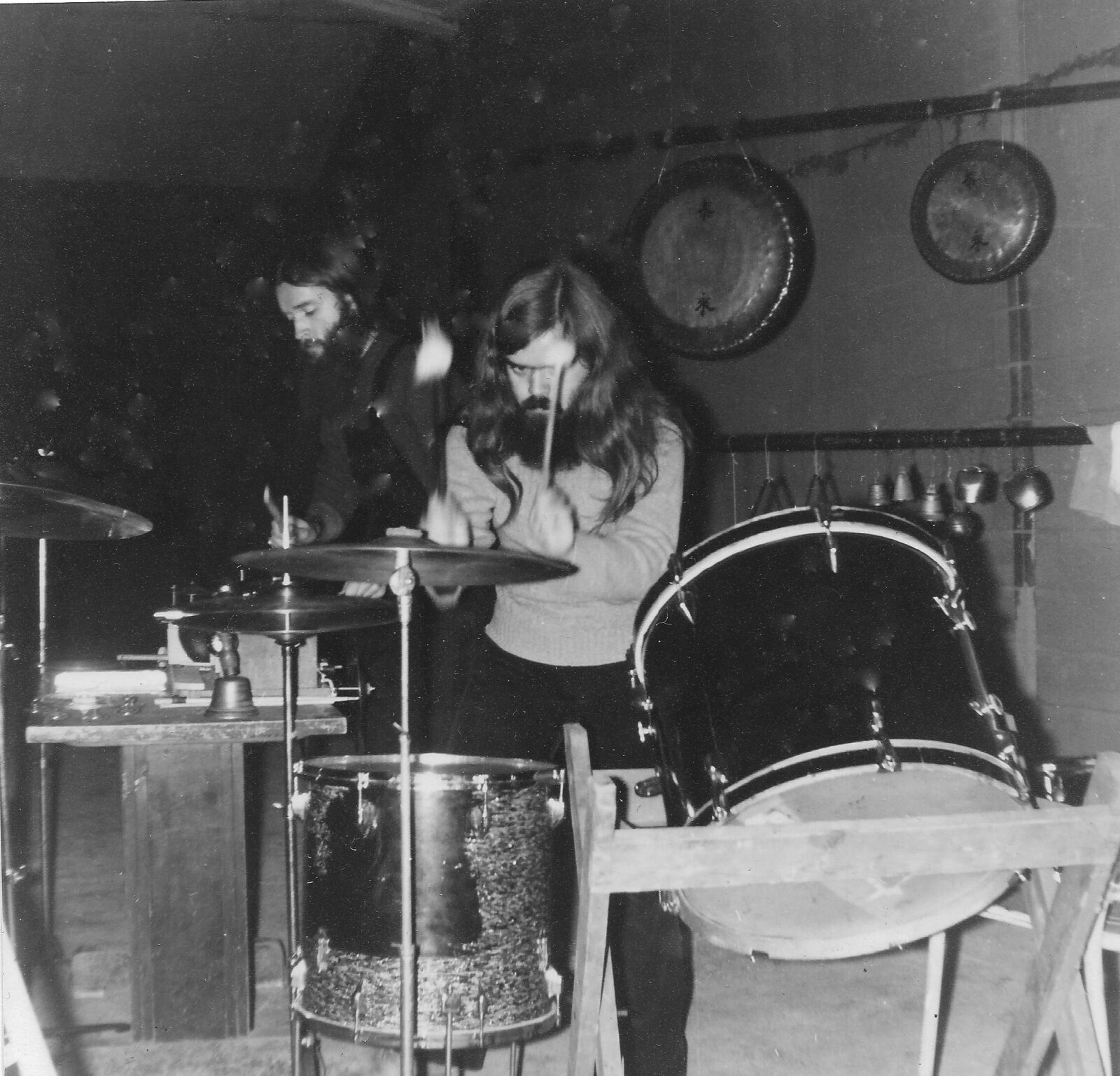

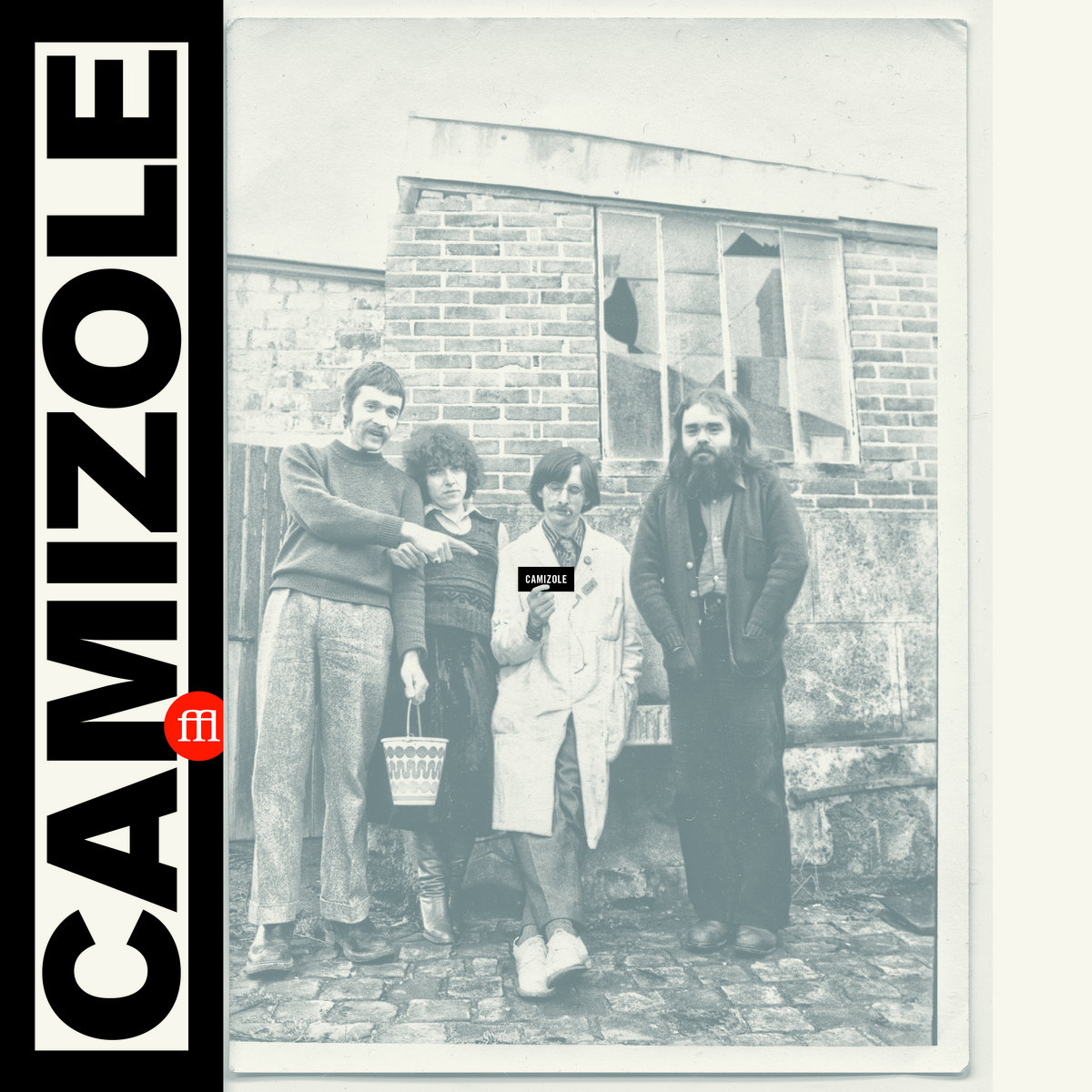

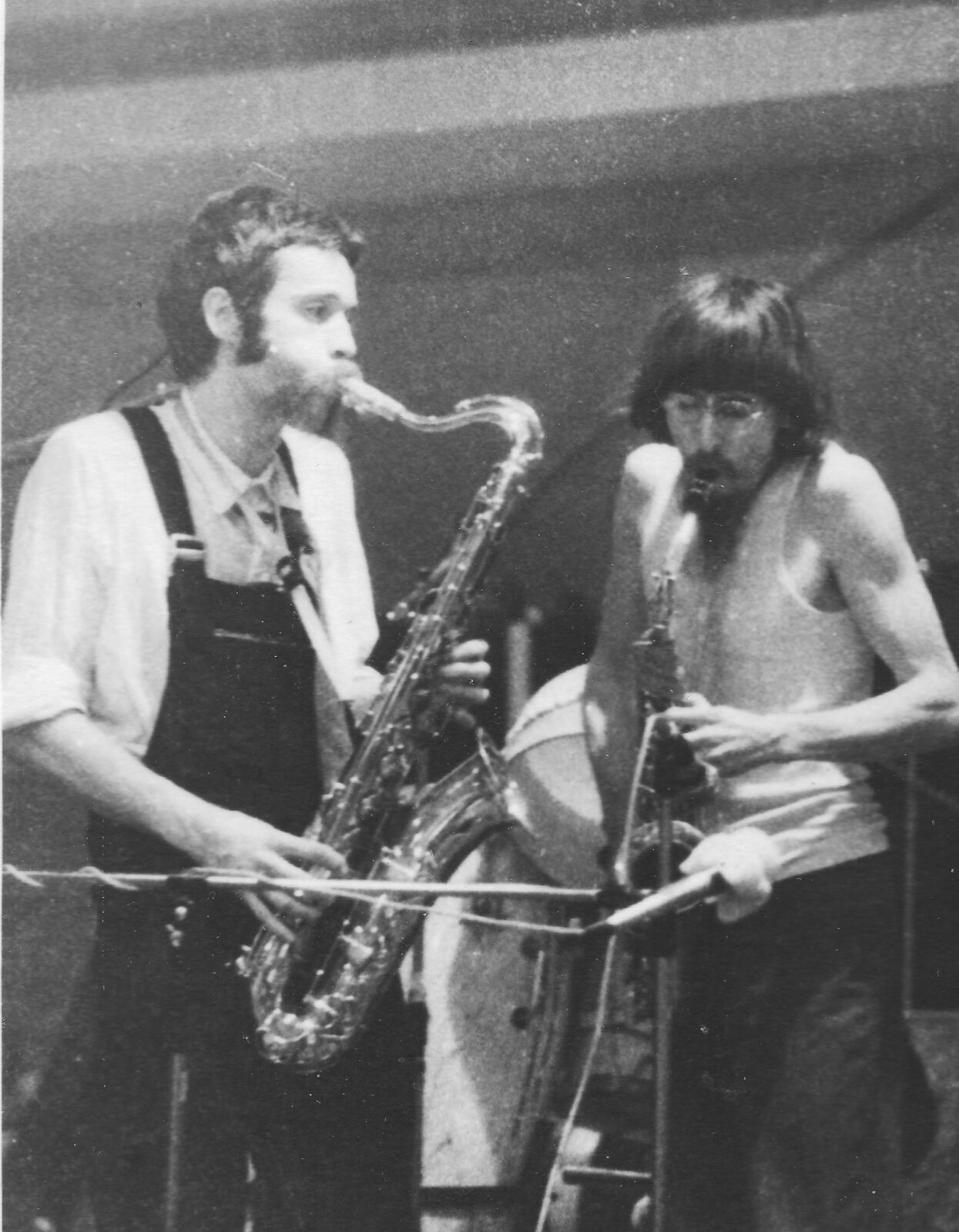

Camizole was a collective of Paris musicians established circa 1970. The band went through many changes, starting as avant-garde jazz, moving to electronic music, before ending up as a hybrid of many styles involving musicians from Etron Fou Leloublan and Lard Free. During their history some 20 musicians passed through the band with Dominique the only constant member. Eventually Camizole transformed into Vidéo-Aventures.

Would you like to talk a bit about your background? Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life?

Dominique Grimaud: I was born in 1950 in a medium-sized town 85 kilometers from Paris. My parents were workers and music was not present in my family. However, as a child I heard popular French songs on the radio and my grandmother sang songs at the end of family meals. At school we learned the national anthem, ‘La Marseillaise’, and ‘Le Chant des Partisans’ which was the song of the French Resistance during the war. I also remember the concerts of the municipal bands on the village square. On July 14 (National day), there were parades of military bands; the power of the sound of their brass impressed me a lot. There was also the regular presence of popular balls. In summary, it was a whole atmosphere experienced by people of the working class in these years after the Second World War which was still very present in the memory of the French. As a teenager, my older brother introduced me to the “pioneers of rock” (Little Richard, Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, Chuck Berry, et cetera). It was a universe, extremely different from what we had known before. But that could only be lived through the purchase of small 45 rpm records (EP 7 inches). Then the English groups, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Animals, The Who, The Yardbirds et cetera. turned everything upside down.

When did you begin playing music?

Quite late, at 19, before that, I was an avid listener to the bands I just mentioned, but I had no idea how it all fit together and what techniques were behind it all.

What sparked your interest in analog synthesizers and the first samplers?

In the early seventies, I experimented on various instruments: double bass, violin, transverse flute. I built a kind of oversized zither that looked a bit like a piano frame. All this was not entirely satisfactory. Synthesizers, echo chambers, then samplers were obvious for a sound researcher like me, who had no conventional technique.

When did you decide that you wanted to start writing and performing your own music? What brought that about for you?

From the beginning with Camizole we played our own music, without going through the phase of learning an instrument.

Was Camizole your first band or were you part of any other projects before it?

Yes, Camizole was the first formation in which I played from 1970. But, we were not at all like the other groups in our city, who all did covers of songs by well-known groups. We were totally into something else.

How did you meet Jacky Dupéty?

Jacky was the same age as me and he was also the son of workers. But thanks to a teacher who had spotted him, he was able to enter an art school in Paris. It made all the difference. Jacky had met Alan Silva, one of the many free-jazz musicians who resided in Paris. Jacky knew the counterculture, the Dadaist, the Living Theatre, Stockhausen, et cetera. He had been active during the strikes and demonstrations of May 1968, and this had led to him being expelled from his art school. Back in our small provincial town, he was equipped with knowledge and experience that for my part I was almost completely unaware of. It was he who was at the origin of our first public performances, and who motivated us to improvise in music, when we had no instrumental technique.

What was the original concept behind Camizole? Was improvisation the main ingredient or did you allow some structured orchestration to be part of the group as well?

There have been several periods during the eight years of Camizole’s existence. Somewhere the concerts were more or less organized, with more or less determined interventions.

Others where improvisation was total, where anything could happen. Some concerts were given with the support of a pre-recorded magnetic tape. Sometimes, the happening aspect was more present. It was very open in substance and in form.

Would you like to talk about the SouffleContinu 2018 compilation… Those are tapes from various occasions and places in France, throughout 1977 and offer an insight about what you were all about. What can you tell us about the recorded material and what were some of the main influences for you?

This album is a full cover of the album we recorded in 1977 for Tapioca, the label of Jean Kakaros, but which was not released at the time. It was a recording session open to the public during which the music was completely improvised. Except that we had forced ourselves to play fairly short pieces, in order to better correspond to the format of an album. Obviously, this time the happening side did not exist at all. The album was to be completed with an excerpt from a stormy concert that we had given as the opening act for a well-known hard rock band, during which part of the public had tried to expel us from the stage. We thought that was a good testament to how sometimes it was for us at festivals. For the double album released by SouffleContinu we have added excerpts from various concerts of the same year.

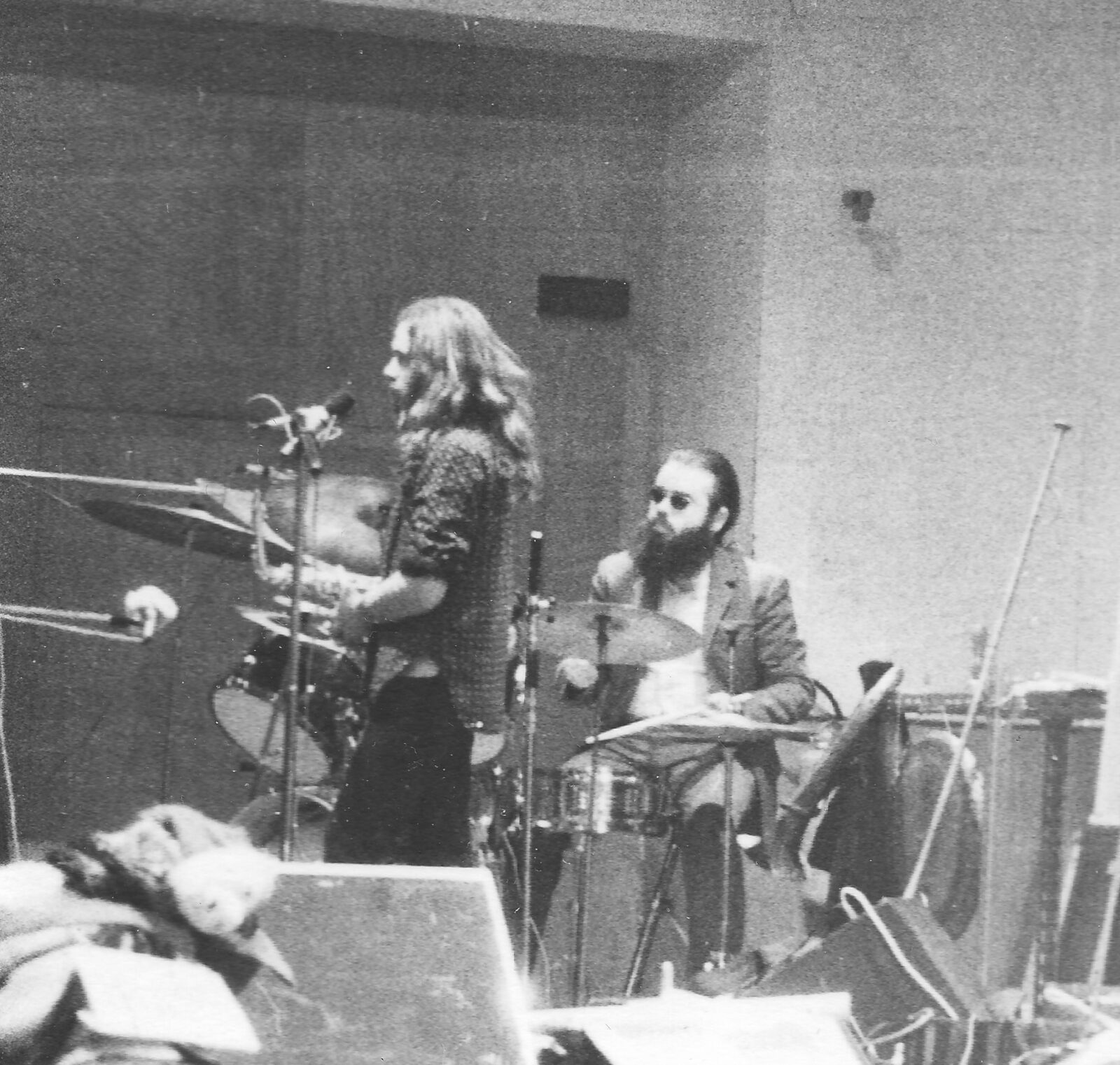

As well as our very first recording session which took place at the Maison de la Radio. It was supervised by Pierre Lattès, a well-known columnist, radio man and producer at that time. With this session, we can see what Camizole’s music was like when it was a little more organized. At that time our influences were many and diverse. We could cite American free-jazz, The Mothers of Invention, Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band, Faust, Neu!, European free jazz, Henry Cow…

“The French underground was strongly marked by the American free jazz”

French underground had a very specific sound, to what do you contribute it?

The French underground, in the years following May 1968, was strongly marked by American free jazz, because a good part of the musicians of this movement were performing in France at that time. They found a much better reception there than in the United States. Some of them have also settled permanently in France. This corresponded well to the libertarian spirit of the years which immediately followed the strikes, the demonstrations, and the barricades of May 1968. These French musicians were also influenced by innovative musicians like The Mothers of Invention or Soft Machine, who themselves were enthusiasts and connoisseurs of older French artistic movements (there was an interesting feedback effect there). The French underground also drew on great French musical figures, such as Erik Satie or Pierre Henry. Finally, many included, in a parodic way, music from popular dances and French songs.

What about ‘Camizole 1975’? Those recordings sound completely different and are much more synthesizer oriented.

At that time, I was very excited about what was coming to us from West Germany, the first albums from Kraftwerk, Neu!, Cluster, Can, Faust, et cetera. My companions from Camizole did not really share my passion. So, I left them, and after two or three solo concerts, I formed a new Camizole with Bernard Filipitti.

There was this good contact with Klaus Schulze who wanted to produce our album, but I found that the music of our duo did not stand out enough from models from across the Rhine and I decided to stop after less than a year of existence.

SouffleContinu have another fantastic recording out that depicts the post 1978 period when the group Camizole merged with Gilbert Artman’s Lard Free. How did that come about?

In 1978 Lard Free’s staff was very fluctuating around Gilbert, the only permanent member. Lard Free was mostly reduced to a duo, with the return of Philippe Bolliet, one of the founding members. Camizole and Lard Free were scheduled quite often at the same festivals. Gilbert loved Camizole’s freedom and audacity. On our side, we admired the concerts as much as the albums of Lard Free. The merger happened naturally, without us even talking about it before. We put the material of the two groups on the stage and we played together without asking any more questions.

Besides that both groups were part of thriving French underground, your sound was quite different.

The style of each of the two groups complemented each other well. It sounded louder, more beautiful, richer. We were very happy with the result, so we repeated the experiment a few times.

How did you first meet Monique Alba and what led to the formation of duo Video-Aventures?

Monique Alba was part of Camizole’s entourage. In music, it seems that I don’t like to repeat myself for a long time, I like change, I like to experiment with other things.

Beyond the experience with Lard Free in 1978, I found that Camizole was no longer evolving much. I had the desire to devote myself more to recording work. I wanted to experiment, no longer on stage, but in a more thorough and patient way in the laboratory.

In 1981 you released ‘Musiques Pour Garçons Et Filles’. The record is full of unpredictable experiments. What was the technique behind making this record possible?

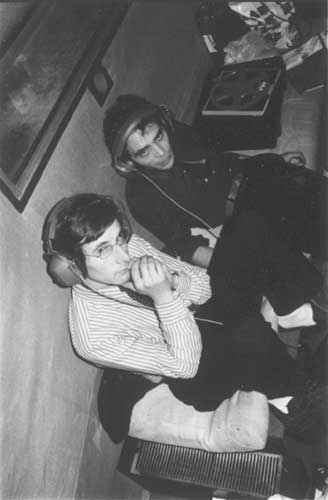

We bought a Revox A77 two-track tape recorder and for a year we worked on recording musical bases, mainly with the Synthi AKS modular synthesizer. Then we offered the best of these to musicians we had met over the previous two or three years and whom we appreciated both musically and humanly. The album was recorded in November 1979.

The lineup of musicians that were part of it is impressive. You had Gilbert Artman, Jac Berrocal, Han Buhrs, Guigou Chenevier, Cyril Lefebvre. Did you select musicians best suited to each composition?

No, everyone intervened as they wished and on the pieces they liked. Everything was done in total freedom and in complete confidence.

What’s the story behind 1984 ‘Camera (in Focus) / Camera (al Riparo)’?

Before the release of the first album ‘Musiques pour Garçons et Filles’, we had already started working on the second album, which was recorded in 1981. Jac Berrocal was the privileged guest of these sessions.

Otherwise, it was almost the same team as the first one. Except that Gilbert Artman had moved on to the role of artistic producer, because we were completely enthusiastic about the very particular work that Gilbert had done on two tracks during the mixing of this first album. The very important role of the artistic producer was unfortunately too often neglected at that time by French underground groups. I learned a lot from the very particular working methods used by Gilbert Artman, they strongly influenced my own way of working in the studio. This second album was less successful when it was released than the first. But thereafter it still benefited from three different reissues, including a very beautiful one in the United States, on Jason Willett’s label Megaphone.

Around that period of time you also worked with Guigou Chenevier on his solo albums.

My contributions to these albums were relatively limited, but they were fun to do.

What can you say about the association Dupon et ses Fantomes that you started with Etron Fou Leloublan?

This collective did not last very long, because each group had different problems. Moreover, we were geographically distant and the communication was much slower back then. Between two meetings, a few months apart, the situation of some groups had sometimes changed a lot and the projects previously set up became obsolete.

Groups like Mozaïk and others joined you. Can you name those bands? What was the main aim for this association?

Camizole, Etron Fou, Mozaïk and Grand Gouia were the groups behind this collective whose goal was to try to organize us outside the official circuits.

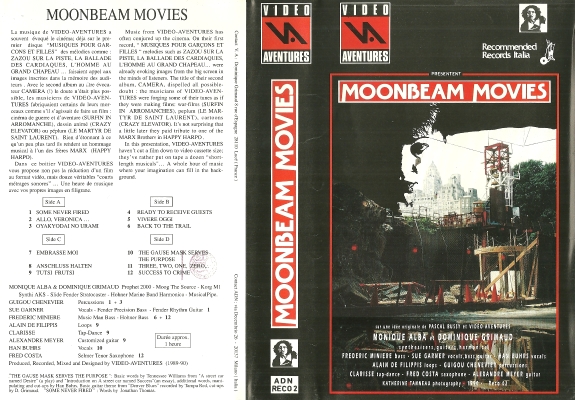

How did ‘Moonbeam Movies’ come about?

Several tracks of ‘Camera (in Focus) / Camera (al Riparo)’ were clearly developing cinematic atmospheres. So we had the idea to push this tendency more strongly. From dialogues and sounds extracted from known or unknown films, we recreated short sound films of more or less five minutes on which we created our own film music. All film genres were represented (western, detective, humor, science fiction, horror, et cetera). The two cassettes were placed in a video cassette case with a cover imitating a movie poster.

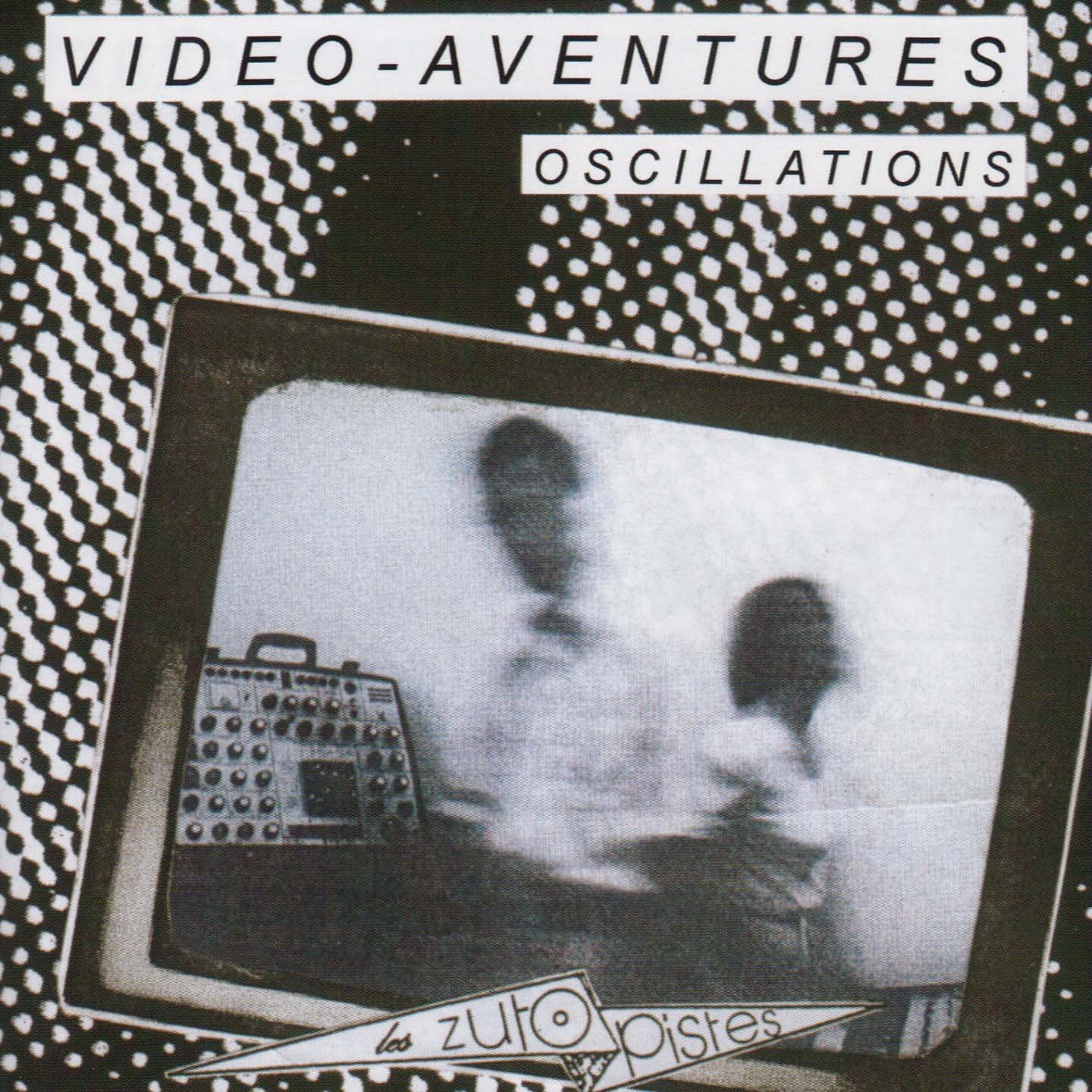

What material is on ‘Oscillations’ compilation?

It’s a compilation made in the 2000’s that highlights the electronic music side of Video-Aventures. It contains a part of the musical bases that we gave to the guests of our albums before they recorded their instrumental parts. There are also some musical bases completely unreleased because they were left unused in the studio. And others that we played only on stage. The synthesizers are the only instruments present on these tracks.

How was it to work with Gilbert Artman’s Urban Sax project?

What was interesting was to participate in a project that was both innovative and popular. It is very rare that these two words can be combined.

How did you approach your 1999 release of ‘Slide’?

It was a sound installation that also led to an album. The word ‘Slide’ refers to the technique of playing with a bottleneck on the strings of a guitar, but also to the small photograph on a transparency that is projected onto a screen. With this double theme as a starting point, I reproduced, in a totally unconscious way, one of my favorite games when I was a child: the construction of an Indian camp, in which each evening, I invited one or several musicians to share a moment of improvisation. For the album, recorded in several studio sessions, I recorded five long musical bases on which the thirteen guests improvised or placed what they had prepared.

I think one of the most overlooked projects in your discography is ‘Les quatre directions’.

It is an album also turned towards the Amerindian philosophy. A single piece of sixty minutes whose score in the shape of a circle was reproduced in an article called Partitions Excentriques, in the magazine Art Press (I was rather proud that it appeared alongside those of Xenakis, Anthony Braxton, Stockhausen, Morton Feldman, John Cage…). The piece starts at ground zero, evolves slowly into four parts, and then returns, after an hour, to its starting point. The musical instructions are audible and expressed in Sioux-Lakota language. The album was published by the Chicago label Locust.

The initial plan was to make a double vinyl album, but it was shortly before the label ceased operations and the project was limited to a compact disc version. Let’s hope that a label will have the desire to reissue it in its originally planned version.

Just when the pandemic hit, you released ’19 Feedbacks’. What kind of concept have you had in mind when working on it?

I thought that I was a bit too much locked into the role of the so- called specialist of the French underground of the 70s and 80s. I don’t like to be locked into a role, a definition, a musical style, whatever it is. ’19 Feedbacks’ is a tribute to the music of my adolescence. The ones that fascinated me and that built my musical culture in the 60’s: The Beatles, The Rolling Stone, The Animals, The Yardbirds, The Mothers of Invention, Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band and many others. I used this extremely rich sound material to create new sounds and personal compositions. I think that the music we listen to during our adolescence, marks us deeply and during our whole life.

Maybe I’m completely wrong, but it’s something in the way of Faust’s debut, where you hear fragments of The Rolling Stones’ ‘Satisfaction’ and the Beatles’ ‘All You Need Is Love’ fading in and out. Like a reintegration into modern experimental music.?

No, not at all. In ’19 Feedbacks’, it is very difficult, almost impossible to recognize the original tracks. The sound material has been completely changed and leads to something else.

What about your project called Grimo?

I had spelled my name this way at the time of ‘Slide’ in order to pay homage to, and also to make visible, the influence of Chomo on this project. His real name was Roger Chaumeau, a painter, sculptor, builder, musician too, an artist out of the ordinary and out of the commercial circuits, who lived as a hermit in a forest 50 kilometers from Paris where he had built, with recycled materials, the Village d’Art Préludien. Under this pseudonym, I also recorded the two volumes of ‘Rag-Time’, the second of which is a duet with Pierre Bastien. These are two albums in the pataphysical and humorous spirit of the In-Poly-Sons label for which they were intended.

What about Peach Cobbler with Rick Brown and Sue Garner? Where does your fascination with Delta Blues come about and how was basically the idea behind Peach Cobbler started?

As a youngster, I had listened a lot to the blues played by English and American bands, like The Rolling Stones, John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers, Canned Heat, Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band, et cetera. Two decades later, in the early 90’s, I immersed myself with passion in the original versions of these rural and delta blues that were recorded between 1926 and the end of the 30’s. I learned the bottleneck technique and open tunings. I bought an antique National steel guitar with a resonator, the instrument of choice for many of these artists. Of course, my intention was not to reproduce, more or less faithfully, these beautiful songs. They were related to a very difficult life, often dramatic with a lot of injustice, violence and crimes. These men were in turn vagabonds, prisoners, preachers, sharecroppers et cetera.

It was clearly not my experience. However, as we all know, the defining influence of this music made it universal. We recorded in New York with the sound of the city, the mechanical breakdowns of the van, our conversations during rehearsals, et cetera. Then these recordings were completed in France. In the end, these are classic blues songs in a road movie context, crossed by contemporary and abstract music.

Tell us about your collaboration with Veronique Vilhet which resulted in several albums.

Véronique Vilhet comes from the band Johnny Be Crotte, too little known from the post-1968 underground, (a double single has been re-released by In-Poly-Sons) some of whose members went on to play in Etron Fou Leloublan, Barricade and ZNR. On her side, Véronique had joined the street theater group Royal de Luxe where she played percussion and sampler. Our duo started in 2008. We have released three albums, a fourth album is in the process of being pressed and we have recorded a good part of the fifth. Since the beginning we are supported by David Fenech who polishes our sound, for example, by taking care of our pre-mastering. Our will for each new album is to experiment something radically different from the previous one. The first album ‘AAHH!!’ released by Bam Balam Records, is based on monolithic drums and vintage synthesizers. The second album, ‘Îles’, is based on a Stratocaster tuned in open tunings. The third, ‘J’Aime Tout Ce Que Fait Le Ciel À N’Importe Quel Moment’, in the words of Richard Brautigan, is exclusively devoted to Véronique’s voice, always with this will of sobriety and purity of sound. The next one explores the possibilities of the saxophone and the bass clarinet with, of course, the drums.

Is there still any unreleased material that you would like to make public?

Yes, there are several things coming out. But, the pressing times have gotten so long that I don’t like to talk about things until they’re out.

Music making is not your only passion. You chronicled the French musical underground post-68 by publishing the books Un Certain Rock and many more. Would you like to tell us what you have written so far and share some further explanation of what we can find in the books?

In 1977 I noted with regret that the place given to French musicians in the official music press was very minimal (of course, I’m talking about those who offered something other than a pale copy of the English and American models). They were almost totally ignored. I had the idea to gather the few short articles that appeared here and there, reviews, often only a few lines, biographies and unpublished interviews, photographs, pieces of record sleeves, et cetera. A kind of puzzle, a whole documentation gathered in a single work (Un Certain Rock (?) Français volumes 1 and 2, in 1978). Thirty years later, Eric Deshayes proposed to me to co-write with him a more conventional book on the same subject which was published by Le Mot et le Reste, in 2008 under the title L’Underground Musical en France. It sold well and was republished in 2012.

What is your methodology when it comes to research?

On these musicians of the post-1968 French underground… From the beginning of the 70s, I accumulated archives: albums, articles, magazines, concert and festival programs, cassettes, biographies, pictures, posters. That is until about the beginning of the 90s. I also exchanged written correspondence with musicians and met them backstage.

Chris Cutler and Recommended Records had a huge impact on the scene. He is one of the few that recognised the French and German underground. Speaking of that, how would you compare the French-German groups and its creativity?

Yes, the role of Chris Cutler was important, with Rock in Opposition and especially with Recommended Records which had given birth to several other Recommended labels in France, Italy and Switzerland which constituted a very creative network. There was also Archie Paterson in the U.S. with his Eurock magazine. The German and French bands proved each in a different way that it was possible to go beyond the English and American models. They knew how to combine these Anglo-American influences with the cultural, historical and political particularities of their respective countries. And they have thus created extremely original and relevant new music. But it is clear that German rock has been more internationally recognized than the French underground.

Is there anything else that currently occupies your life?

Music occupies a large part of my time. Apart from that I live like everyone else: I read, I listen to the radio, I walk, I cook, I ride my bike and I do some DIY to maintain my little house.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thank you very much Klemen, because I know how important interviews, articles and reviews are for musicians in my category.

Klemen Breznikar

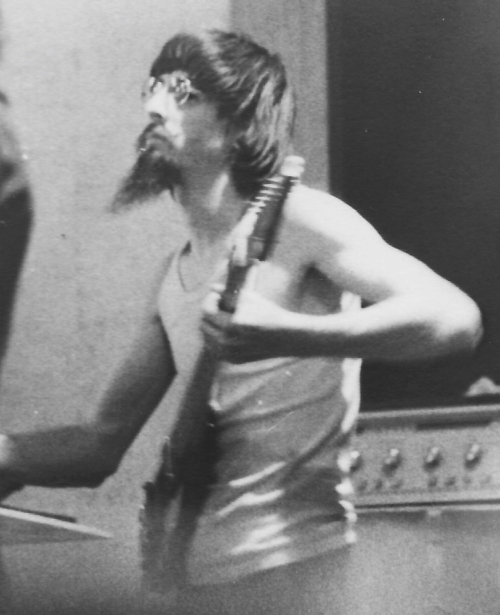

Headline photo: Camizole

Dominique Grimaud Official Website / Facebook

SouffleContinu Records Official Website / Facebook / Twitter / Bandcamp