Van der Graaf Generator | Interview | Guy Evans

Van der Graaf Generator is an English progressive rock group formed in 1967. The band started at the University of Manchester, but settled in London where they signed with Charisma.

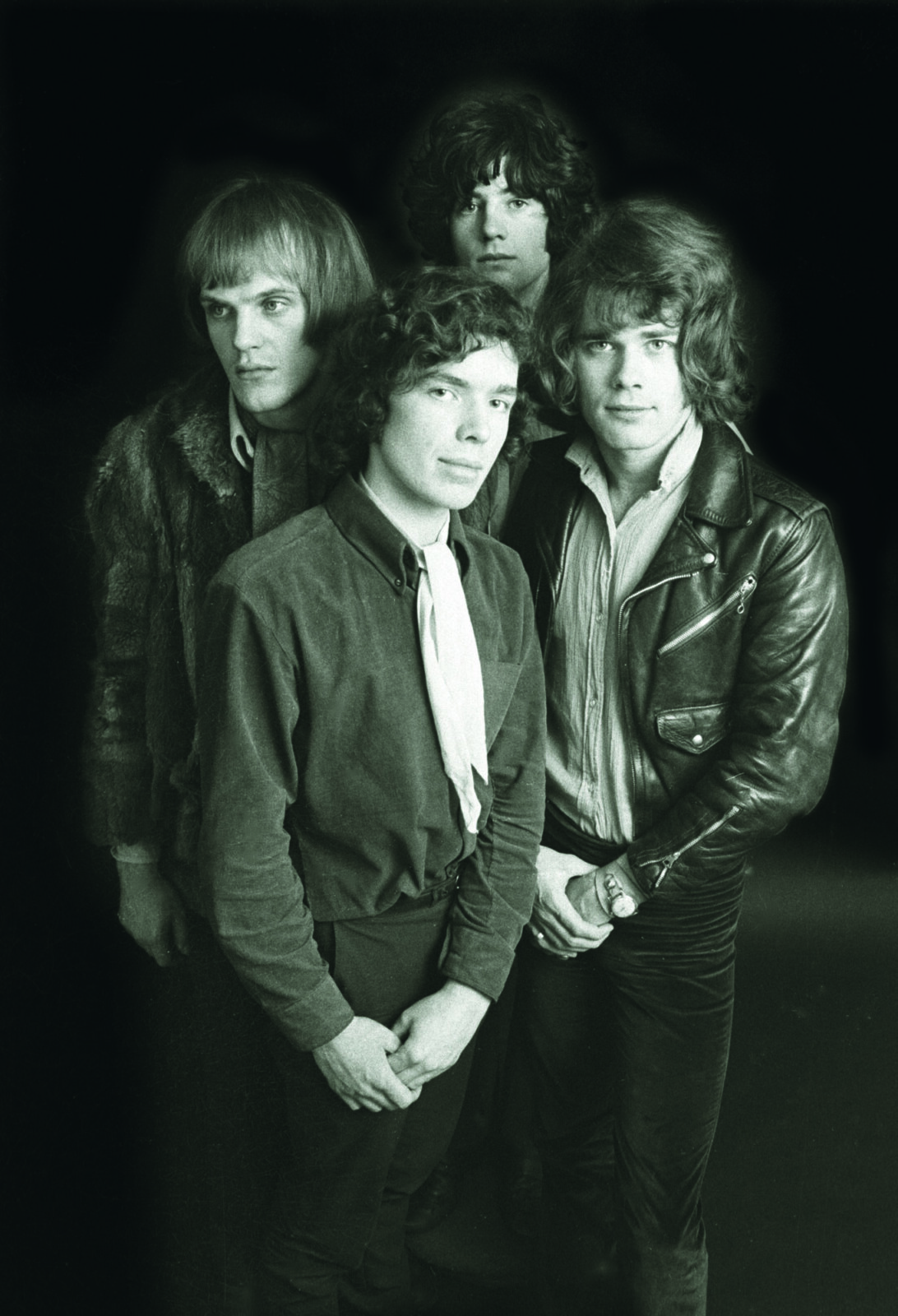

Van der Graaf Generator went through several incarnations in their early years and eventually stabilized around a line-up of Peter Hammill, Hugh Banton, Guy Evans and David Jackson. In the following interview I spoke with Guy Evans, their percussionist. Whilst at the University of Warwick (1965–68), Evans played in the university band The New Economic Model. He became a member of Van der Graaf Generator in 1968 until 1978, and since their reformation in 2005. In addition to his work in Van der Graaf Generator, Evans has collaborated with many musicians, including his work with Echo City constructing so-called “sonic playgrounds”.

“To immerse myself in fresh challenges and just play”

You mentioned that you’re slowly getting back on the road. What are some upcoming gigs for you?

Guy Evans: Van der Graaf Generator has a big European tour set for Spring 2022, starting with five UK dates. We’ll be playing old haunts like The Paradiso in Amsterdam, The Trianon in Paris, Fabrik in Hamburg, and a whole mixed bag of interesting-looking unfamiliar venues, including a few small clubs. We are also scheduled to play dates in Finland, Norway and Sweden in October/ November.

COVID-19 restrictions notwithstanding. But first, we take the plunge with a set at The Beautiful Days Festival in Devon on August 22nd. “Oh no, I must have said Yes!” Didn’t someone say that?

I’m also pleased to be back playing live with AMM All Stars (more on this follows). We’ve started doing a Friday morning improvised session at The Betsey Trotwood pub in Farringdon. This is recorded, then broadcast the following Wednesday on Ben Watson’s, Late Lunch with Out To Lunch show on Resonance FM. It’s especially challenging, because I’m limited to playing things that I can carry on a bike.

You must be pretty excited to be back on the road after so long. How are you coping with the current pandemic and what are your predictions for the future? Do you think the music industry will adapt to it?

I’m fine. I keep pretty busy. Eighteen months ago, I was invited to play with Ben’s Watson’s improvising ensemble, AMMAS, which later morphed into its lockdown xenochronic version, XAMMAS. They’ve both sources of endless creative possibility and self-inflicted workload.

AMMAS began as a regular hour of improvised music, broadcast live on Ben’s Late Lunch With Out To Lunch show on Resonance FM every Wednesday. During lockdown, Ben came up with the idea of using xenochrony, a term coined by Frank Zappa to define his technique of combining musicians’ performances recorded at different times, maybe in different locations, and frequently for different tracks, into new music that exploits the resulting rhythmic anomalies.

A bunch of people from all around the globe contribute recordings that Ben edits into new xenochronic pieces. They can be solo improvisations, field recordings, spoken word, multitracked creations, or responses to pieces that others have already submitted. The responses may or may not be used in sync with their stimulus.

In this context, I’ve been co-creating with (among others) ex-Minutemen and Stooges bassist, Mike Watt, Machine Gun co-founder Jair-Rohm Parker Wells, multi-instrumentalist/composer Graham Davis, the electric guitars of sculptor, Eleanor Crook, and Marxism and LSD history pundit, Dave Black, the anarchically mysterious Psychedelic Bolsheviks from Sheffield, Melbourne-based improviser James Wilson, and my old mate from Echo City, Paul Shearsmith, now based in Stuttgart. We are a record company’s nightmare – a band that can’t decide who’s in it, what it’s called, or what it’s musical shape is. I love it. Sometimes it feels a bit like I’ve been inducted into a cult, but so far no one’s asking me for money, or talking Operating Thetans!

As for the future, it’s anyone’s guess whether performers can invent enough smart ways of working, or if government and/or the music business itself will be smart enough to willingly change parts of the legal/financial status quo to allow musicians’ international careers to continue, (if only to protect their own revenue). Van der Graaf Generator is relatively lucky, in that we have a well-established, enthusiastic fan base that allows us to broadly predict revenue and follow a break-even-plus-a-bit plan. It’s also re-assuring for promoters who can see the sense in taking a financial risk or two in order to support us. This won’t be the case for younger bands trying to establish a career –even those with a record deal. I don’t envy anyone starting out in this environment.

Can we talk about the 2016 album by Van der Graaf Generator ‘Do Not Disturb’? That was such a fantastic record.

Making it was a great experience. We went back to how we used to do it- getting our heads around sketched out pre-existing riffs and sequences at home, coming together for a week’s studio-based development, then returning to the same studio a week later to record all the backing tracks live inside a week.

There was, dare I say, an element of tenderness about it – the awareness that it could be the last album. However, we’re now really fired up about playing together again, so who knows?

I also noticed that you played on Aline Frazão’s album, ’Insular’. Was that a session work?

Aline’s producer for that was Giles Perring. We have a long musical and family history. Giles plays percussion himself, but felt that the album would benefit from my input on the kit on one track. He also wanted me to engineer and produce his percussion on other tracks. I was slightly nervous about my own drum part, which I pre-recorded at home without hearing the bass. Simon Edwards was likewise required to record the bass part without hearing what I’d played! (Simon is the go-to session bass guy for Latin stuff in London. His feel and time are phenomenal). I was relieved to find out that our playing dovetailed perfectly. All very Giles. Anyway, I got up to Jura, which I love, and managed to fit in some great wild swimming. It would be nice to meet Aline someday.

“Simply exploring human musicality for its own sake is usually pushed aside in the pursuit of narrowly defined notions of excellence and virtuosity”

I would love to take some time to discuss the concept behind Echo City, a sound sculpture project founded in 1983 by you, Giles Leaman, and Giles Perring.

Well, we’re already in hot water with the question! I’m guessing that the source of your list of originators is Echo City’s website, which omits Dave Sawyer, following his bizarre insistence that he was never a member of Echo City! Nevertheless, for the record, and to swerve any possible accusation of failing to credit Dave’s significant input, I’d venture that Dave is a wildly talented and original musical inventor whose design vision influenced what we made long after he’d left the team.

To get back to the question, (and hoping that the lawyers can stay in their cages!), the original inspiration came via Ros Bandt, who’d built what she called a Sound Playground in Melbourne in 1982. We never saw her workup close or played it, but got the impression that it was a pretty carefully crafted art piece. This gave us the idea to build our own rather different version in London, where there were already some ready-made adventure playgrounds on what had been waste land, often in deprived parts of the city. Here children and young people were allowed to play on ad-hoc equipment crudely constructed from scrap materials, and could sometimes build makeshift structures themselves.

We thought that if we made approachable, large–scale instruments on one of these sites, and built them sturdily enough to withstand the onslaught of disaffected kids, this would invite and encourage “sonic play”.

We shared a belief that simply exploring human musicality for its own sake is usually pushed aside in the pursuit of narrowly defined notions of excellence and virtuosity. The habitual reaction to anyone “making a racket” is disapproval, and it’s normally only “proper” musicians who are thought capable of making music of any worth. (Imagine such thinking applied to, say, sport, and you’d end up with professional athletes being the only people approved to run and jump!).

In the case of music, an exclusive set of aesthetics has been progressively reinforced by centuries of rich patronage, and more recently by the powerful marketing machine of the pop industry, to produce a culturally distorted and elitist perception of “music” itself. Our idea worked. People “got” it, and we started getting a lot of attention, some from unexpected quarters like play equipment manufacturers and film makers.

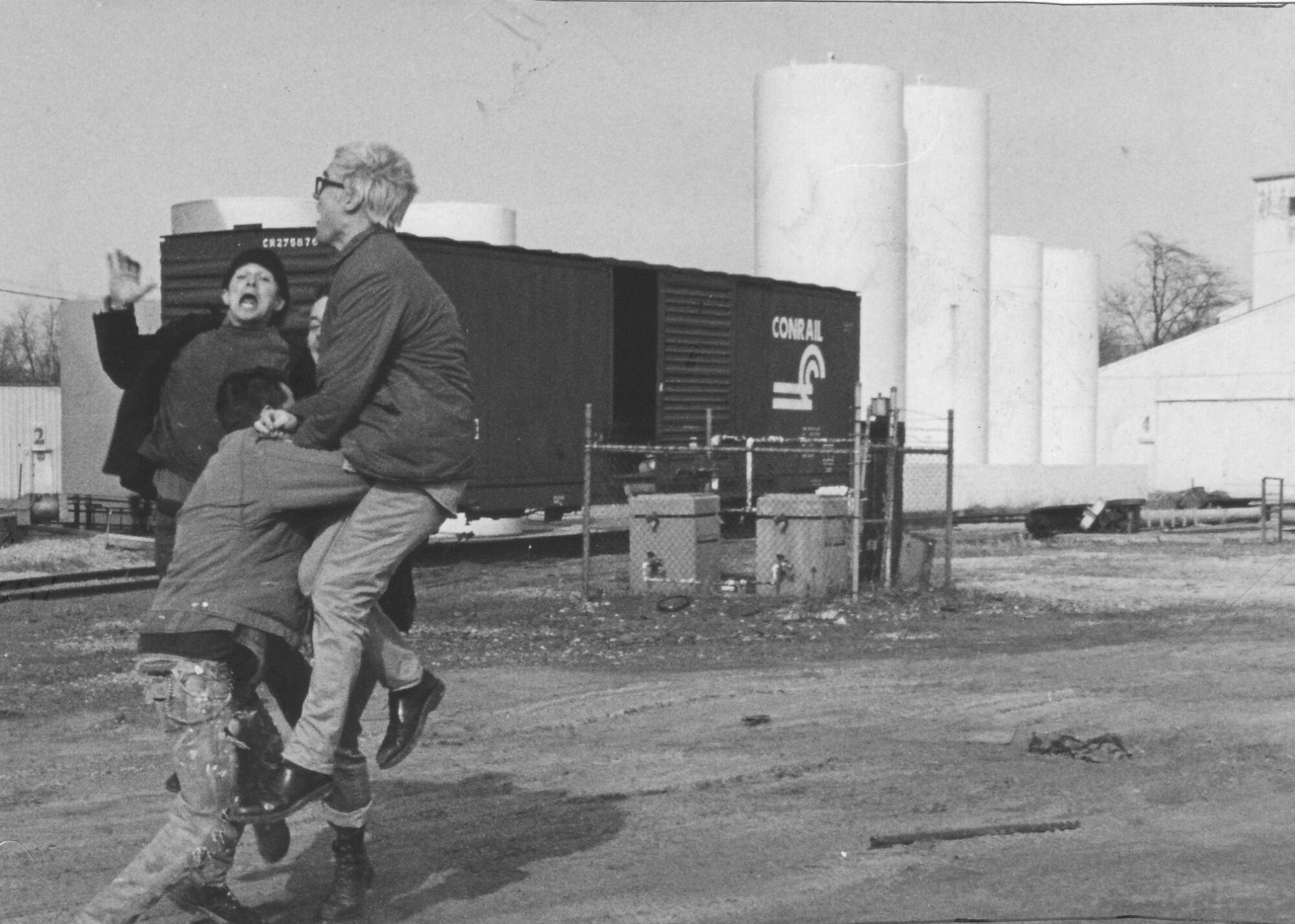

Straight after we’d finished our first playground in Bethnal Green, which we dubbed “Echo City”, our ideas were subjected to an extreme test when we were asked to build musical structures for adventure playgrounds especially designed for disabled children. To achieve this, we set up workshops on site so that we could work closely with the children and staff to develop ideas.

We simply rejected any prototype that couldn’t take the punishment, or proved unpopular, and concentrated on what worked. This involved plenty of playing and interaction. It was an intense, immersive introduction to the worlds of people whose physical operation, means of communication and in some cases, mental processes, could be very different from our own. It paved the way for all of Echo City’s future collaborations with people with physical, mental and/or learning disabilities, which continued throughout its thirty years of operation.

It wasn’t all wonderful. Sustained cacophony gets exhausting, and simply putting people in front of experimental instruments doesn’t necessarily produce results that even the most determined sonic outliers would find engaging. We soon felt the need to develop workshop routines to explore improvising techniques, and to look at musical considerations that can be overlooked by people with little experience of playing, or who consider themselves to be unmusical. These might include focused listening, varying dynamics and texture, the use of silence, and the power of a single note or sound. For this we borrowed heavily from the ideas of John Stevens, expressed in the book Search And Reflect.

Alongside all this heavy engineering and socially inclusive improvising, we adopted a rather punk approach to grabbing bits of arts and civic funding that habitually went to comfortably familiar projects. Echo City has considerable in-house talent for presentation, persuasion and outright hype, and we scored some significant successes. In the space of a few years, we were awarded prestigious performance commissions for The Covent Garden Music Festival, The Oris Jazz Festival, and one time, a Canadian Arts Council touring grant shared only with Pierre Boulez. I’d love to know what Pierre would have made of our nine hundred kilos of aluminium and fiberglass objects, plastic storage barrels, oxygen cylinders and polyethylene gas main!

Possibly our most significant coup was to convince The London Innovation Network that a mobile rig made to carry refined versions of our instruments met their definition of a socially useful prototype, and should therefore qualify for funding and technical support. This single development enabled our entire international touring career.

This resource, as well as expanding possibilities for shared sonic play, allowed us to infiltrate high-profile arts environments not normally associated with music – or play. We did installation and workshop residencies for both The Museum of Civilization and The Museum of Modern Art in Ottawa, exhibited at The Crafts Council in London, and won an installation commission for The Glasgow Garden Festival after submitting an entry for their design competition that blatantly ignored the brief. In some instances, we were able to invite our customary “outsider” clientele to share our experience.

We weren’t mere altruistic musical revolutionaries. We were also tremendous hustlers.

It originally started as a sound sculptures called “sonic playgrounds”, but Echo City has since 1985 also performed as a band. What do you recall from working on the 1987 ‘Gramophone’ album?

The very existence of that album is down to a classic bit of Echo City opportunism. After a show in Hamburg with Peter Hammill and The K Group, we all went out for an after-show meal with Uwe and Jutta Tessnow of Line Records. The conversation turned somewhat blurrily to the future of recorded music. Sometime between the schnapps and the bill, I realized that I had in my pocket a rough compilation of Echo City recordings that I’d made to listen to on the road. I handed it to Uwe, and said, “Try this”. A week later he phoned me and said, “We can’t stop playing your music. Everyone here loves it. We’d better make a record.”

We had some pre-existing elements. We’d already recorded the three batphone tracks in 1985, for Andy Metcalf’s documentary, ‘Welcome To The Spiv Economy’. We started work on the album by overdubbing conventional instruments on those existing batphone tracks at Silent Studios in Rotherhithe, where we’d made the original film soundtrack. We also transferred some of our own recent recordings of Echo City to 24 track tape, so that we could add overdubs to them.

Trying to record Echo City instruments in a conventional studio would have been a nightmare, partly because of the scale of the instruments, but also because some band members were unfamiliar with standard studio procedures. They just wouldn’t have had the patience. Fortunately, through the simple expedient of failing to leave after a gig, we’d already squatted the London Musicians’ Collective to use as a store for our mobile rig and as our studio.

The LMC had excellent acoustics. Capturing a good recording was mainly a question of setting up a structure, putting up a pair of PZM microphones, and plugging them into our trusty Fostex X15 cassette four-track recorder. (The arrival of the Realistic PZM mic in high street stores was a godsend . Reputedly the result of an administrative error by Tandy, it went on sale at a price of £22:00, but delivered dynamic handling and fidelity comparable to its rival made by Amcron, priced at £200). I’ve always been proud that ‘Gramophone’, an album largely recorded using two budget mics and the cheapest cassette four-track recorder available, earned a four-star rating in the audiophile magazine Which CD?!

We also recorded some live performances. ‘On Tarr Steps’ was Dave Sawyer’s chance to show off his magnificent Boobongs in front of an audience, providing a welcome break for me and my family from having them played all night in our flat! ‘The Engineer’, originally intended to be a completely different piece, was unexpectedly transformed by amid-performance invasion by Rip Rig & Panic’s horn section, aided and abetted by other LMC regulars.

‘In The Field’ was literally that – two sets of sonic play recordings from the original two playgrounds using handheld machines –one Sony recording Walkman and one JVC mono dictation machine with ferocious built-in compression. The tube train sounds were recorded on the Tube journey from Holloway Road station to Bethnal Green, on a trip from the second playground that we’d built to the first one.

‘The Shimmer’ is a recording of Echo City’s sonic sculpture slung across a river in Cumbria (blatantly ripping-off Cristo). We again used the trusty PZM’s, this time attached to a pair of long bamboo poles that Giles Perring and I held while standing in the freezing torrent. That was the second time that I ended up in the river thanks to ‘The Shimmer’, but that’s another story.

Peter Hammill made a brilliant contribution in the form of his studio which had a decent desk and a 24 track multitrack tape machine, which meant we could produce professional mixes. He also provided a vital production overview. Faced with a mass of unanticipated extra parts and undisciplined overdubs, I’d rather lost my grip on the project. We settled on a strategy by which I set the sounds of the instruments and the effects that we would use, and Peter ruthlessly edited the additional parts until he arrived at what he wanted to hear. The stripped down feel of ‘Spiv’ is very much down to Peter’s vision. If you went back to the original 24 track (wherever that is), you’d find it bristling with multitracked free jazz!

I really enjoyed your collaboration with Sun Ra Arkestra on ‘Eruption Day’.

That was a blast (literally!). I travelled to Jura almost straight after finishing recording ‘A Grounding In Numbers’ with VDGG in Devon. I dropped my kit at home in London, and jumped straight onto a train to Glasgow, grabbing one of the few tickets available after the eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in Iceland, which had grounded all air travel.

The back story is that Giles had bumped into Marshall Allen and Mike Ray in the street the morning after we’d seen The Arkestra play a fantastic gig at The Jazz Café. They were trying to find a shop where Mike could buy a replacement for his lost Harmon mute. Rather than send them on a complex mission to London’s West End music shops, Giles told them that his son, Alfie had a Harmon mute at home, which Mike was welcome to borrow. They all went back to Giles’ London flat, and so began the Echo City/Arkestra alliance.

It wasn’t exactly clear what Giles had in mind for the Jura venture. Not exactly a recording project, more like an extended seminar, some of which would be recorded. Whatever, I wasn’t going to miss it!

Dave Davis and Mike Ray turned out to be brilliant people to work with; inspiring, yet possessed of great humour and humility, with none of the weirdness or condescension that might go with being musicians of that calibre. Just very real and utterly in the moment when we played together. This must have been a challenge when you consider that the eruption caused them to miss days of The Arkestras’s residency at The Café Oto in London. Dave spent a lot of time communing with the seals, and I fixed Mike’s Whammy pedal. I hope it’s still working.

At one point, Mike suggested doing a promenade piece. We set up Echo City structures all around the house, and set a time sometime later to play. At the agreed hour, Dave and Mike emerged from their rooms in full Arkestral finery. We played a memorable set of great delicacy, much of which can be heard on ‘Eruption Day’.

We then had to pack up to get the earliest possible transport back to London to play our two scheduled gigs, and so that Dave and Mike could re-join The Arkestra in their residency. But first we bagged a number of samples of volcanic ash to accompany copies of the CD that we had hastily put together. I wonder, did you ever get your free bag of ash, Klemen?

Is the project currently preparing something new?

There isn’t anything new planned right now, mainly because of the difficulty of aligning everyone’s schedules. Mike Ray especially seems to be permanently on tour, either with The Arkestra or with Kool & The Gang. However, there were several pieces from the original recordings that were not not issued on ‘Eruption Day’ which Giles Perring, Julia Farrington and I recently re-visited and augmented. There are also some live recordings from The Flim Flam club in London. We plan to edit all this into a second volume shortly. It’s a slow burn, this volcano!

I hope you don’t mind if we go back at the beginning? When did you first express an interest in music and what were some of the albums you were listening to early on?

It was more a case of music being impossible to avoid! I have an early memory of sitting upright in my bed with my bedroom window open on Saturday nights, watching and hearing my parents’ big band playing in the ballroom of the hotel opposite. The whole day would have been a frenzy of phone calls, musicians and instruments arriving, arrangements being tried out, and tuxedos being pressed. But I guess my earliest musical memory must be of my mother trying out Sarah Vaughan, Peggy Lee and Ella Fitzgerald numbers all day, rehearsing for Saturday night while caring for my infant self.

The first concert I ever went to was The Count Basie Big Band. I was eight years old, and we had front row seats. It completely knocked my socks off. Basie and Ellington were always on the home turntable, slightly ruining rock’ n roll for me when that came along a couple of years later. It just felt a bit tame. At the time, I really didn’t get what all the fuss was about, especially when our flatmate , a trumpet player called Bill Harris, started bringing home white labels of Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Art Blakey et al. That was music from Mars, and I wanted to go there.

Then came cool jazz – music that played with space and sound. Miles Davis again with ‘Birth of The Cool’ (another white label), but also Gerry Mulligan, Tad Dameron and Thelonious Monk. It sounded more mysterious, less terrifyingly technical than be-bop – something I might even play myself someday. (By then I was dabbling with various instruments including soprano sax and tenor horn, and had started drumming on armchairs).

When it came to rock and pop, it was the records that had a great sound and production that finally won me over – Eddie Cochran, Buddy Holly, The Everly Brothers, Duane Eddy, and of course in the UK, The Shadows.

How did you join The Misunderstood to record two singles and what do you recall from being part of the band? [This was probably months before Van der Graaf Generator?]

Slightly wrong chronology there – one that I’ve seen reported elsewhere. I played with The Misunderstood between the four piece VDGG line-up with Keith Ellis on bass, and the five piece VDGG line-up with Nic Potter and David Jackson. The Misunderstood was where I met Nic.

Joining the band was the result of a brilliantly alert bit of networking by my then girlfriend, Sue Johnson, who worked at Mercury Records. When the VDGG four –piece folded, I was quite miserable and complained that I couldn’t think of any other bands I wanted to play with. There were only two I was excited by, Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band, and The Misunderstood, both American. I guess my depression must have been pretty unbearable, because the day after I made my my declaration, Sue came home and said, “Right, you’ve got an audition with The Misunderstood on Thursday.” I was flabbergasted, because I had no idea that they were even in the country, and I was very much aware of what was going on with bands in London at the time. I could easily have been intimidated by this audition, because The Misunderstood’s manager, Nigel Thomas, had brought in John Mayall’s tenor player, Chris Mercer, to run it. I was evidently in for proper scrutiny. When I arrived, there were two other drummers packing away their gear and looking glum, but I got a friendly vibe from an improbably young looking bass player who had survived the afternoon. We clicked the moment we started playing together. I instantly loved Nic’s sound and feel, his instinctive musicality and his disdain for showboating.

The music itself slightly threw me, because Glenn Campbell and Steve Hoard seemed to have thrown out the soaring psychedelia that had drawn me to the band in the first place, in favour of a more soul and blues-based style. Nevertheless, Steve could really sing, and drumming behind Glenn in full flight with heavily amped, distorted lap steel remains one of my most exciting musical memories.

We began a bout of gigs and recording so intense that we found it difficult to amass enough material and hone our style. But the band really had legs, and we became a great jamming outfit, having fun with whatever took our fancy in the moment. I remember that we did a great version of The Beatles’ ‘She Said’, that finally unleashed the psychedelic beast I had so missed. I don’t think it was ever recorded.

For such a short-lived band, we chalked up an impressive live track record, appearing at Plymouth’s legendary Van Dike Club, the super-hip Country Club in London, and opening for both Chuck Berry and The Who at The Pop Proms at The Albert Hall.

Eventually, negotiating the twin tight-ropes of Glen and Steve’s visa problems and Nigel Thomas’s compulsive (though admittedly entertaining) roguery wore us out. However, out of the ashes, Nic came with me into the re-formed Van Der Graaf Generator, and our old bass player, Keith Ellis formed Juicy Lucy with Glen Campbell. A fertile few months.

“The songs were a very odd cocktail of proto pop tunes”

Can you elaborate the formation of Van der Graaf Generator from your personal perspective?

The band had a few incarnations at Manchester University before I joined in 1968. I have only a vague grasp of what was involved back then. Some of it sounds quite ambitious, especially the line-up that apparently had twenty-one members. I’ve always regretted missing Chris Judge Smith’s flaming drum sticks!

I came into the picture after Keith Gordon, a journalist from International Times covered an arts festival that I was involved in at Warwick University, and saw me drumming in three different bands there. He mentioned that a friend of his in London was managing a band who were looking for a drummer, and suggested I get in touch. The friend was Tony Stratton-Smith, the manager of The Nice, and the band was Van Der Graaf Generator.

The way I tell it is that I failed my audition, and the band didn’t exactly light my fire. I was looking to join something like The Graham Bond Organisation (i.e. good musicians playing hard-edged R&B). I was a big fan of all that stuff, and had, after all, once played a gig with The Victor Brox Blues Train. I saw that there was organ and sax in VDGG so I was optimistic.

I was bewildered therefore to find that the organ wasn’t the much-anticipated funky Hammond, but a strange sounding Farfisa Compact Duo, played by a studious electronics engineer, and the sax was an ancient slide instrument, the likes of which I’d never seen before, wielded by an eccentric-looking bearded chap, along with a typewriter and a bag full of ocarinas. To cap it all, the songs were a very odd cocktail of proto pop tunes, incongruously mixed up with stuff about the occult, Nordic myths and Zeppelins, all sung in a choirboy falsetto. A bit much for a boy from Birmingham!

In truth, as a drummer, I probably fell somewhat short of the band’s expectations, given the company that they were keeping. Their favourite bar was La Chasse in Wardour Street, where all the happening musicians, managers, road crew, journalists in London drank, and where significant networking took place. Here VDGG regularly rubbed shoulders with Mitch Mitchell, Aynsley Dunbar, Brian Davison, Keith Moon, Ginger Baker et cetera. Also, their bass player, Keith Ellis had previously played with Tony O’Reilly in the rhythm section of The Koobas, a well-seasoned outfit from Liverpool, who had opened for The Beatles on their last British tour

Still, we found that we liked each other. I failed to leave, the band failed to fire me, and we began to share the sort of adventures that create bonds, like the front tyre of our van disintegrating at speed on the motorway, extreme audience reaction (i.e. half of them leaving leaving!), and opening for The Jimi Hendrix Experience at The Albert Hall.

There was also a Venn diagram of musical tastes. With Peter, I shared common ground with The Byrds, Harvey Mandel, Creedence Clearwater Revival, John Lee Hooker, Mingus, and oddly, Rodgers & Hammerstein musicals. With Hugh it was The Beatles, The Shadows and the spikier end of contemporary classical music – Webern, Stravinsky, Ligeti, Boulez et cetera. With Keith, it was The Band, Traffic and Charles Lloyd.

And I found that despite the very distinctive nature of the songs, I was allowed tremendous scope in my choice of playing styles. The more extreme I got, the more they seemed to like it. Dramatic heavy rock? Fine. Power pop ballad? Fine. Free Jazz? Excellent. Abstract weirdness? But, of course!

So I grew to identify more and more with this improbable band of misfits, though (to borrow a great Geoff Dyer joke) there was more than a touch of Stockhausen Syndrome about it!

Being in the forefront of the then upcoming “progressive rock movement”, what influenced your band the most?

I’d say Jimi Hendrix, the emergence of the recording studio as a creative tool, and each other. With the advent of prog, it had become fine, laudable even, to stretch the boundaries of rock/pop/blues and the conventions of pop lyrics, and to experiment with form. Otherwise, we were hardly influenced by other prog bands at all, certainly not with lyrics, or the type of classical influences that emerged in our music.

Our tendency towards the trickier, more atonal end of things grew out of shared interest. Strangely perhaps, for people who could have quite divergent tastes, we all liked that kind of stuff. The one other person in rock I can think of who championed anyone in that area was Frank Zappa, with his obsession with Edgard Varèse, oh – and of course, The Beatles who’d made a nod towards Stockhausen with ‘Revolution No. 9’.

How did you get signed by Mercury to record ‘The Aerosol Grey Machine’? Those were the very early days of the band where you were still searching for your signature “VDGG sound”…

This was because Peter had already signed his own punitive deal with Mercury. ‘The Aerosol Grey Machine’ came out on Mercury in a deal that released Peter from that contract, to allow the whole band to sign a better deal with Charisma. The Mercury experience wasn’t all terrible. They had a comfortable, plush office in a luxury apartment overlooking Hyde Park, which made it a great place for impoverished musicians to hang out, stay warm and get free coffee. Our label mates were Graham Bond, The Eyes Of Blue (who became Man), and David Bowie, so we were in interesting company.

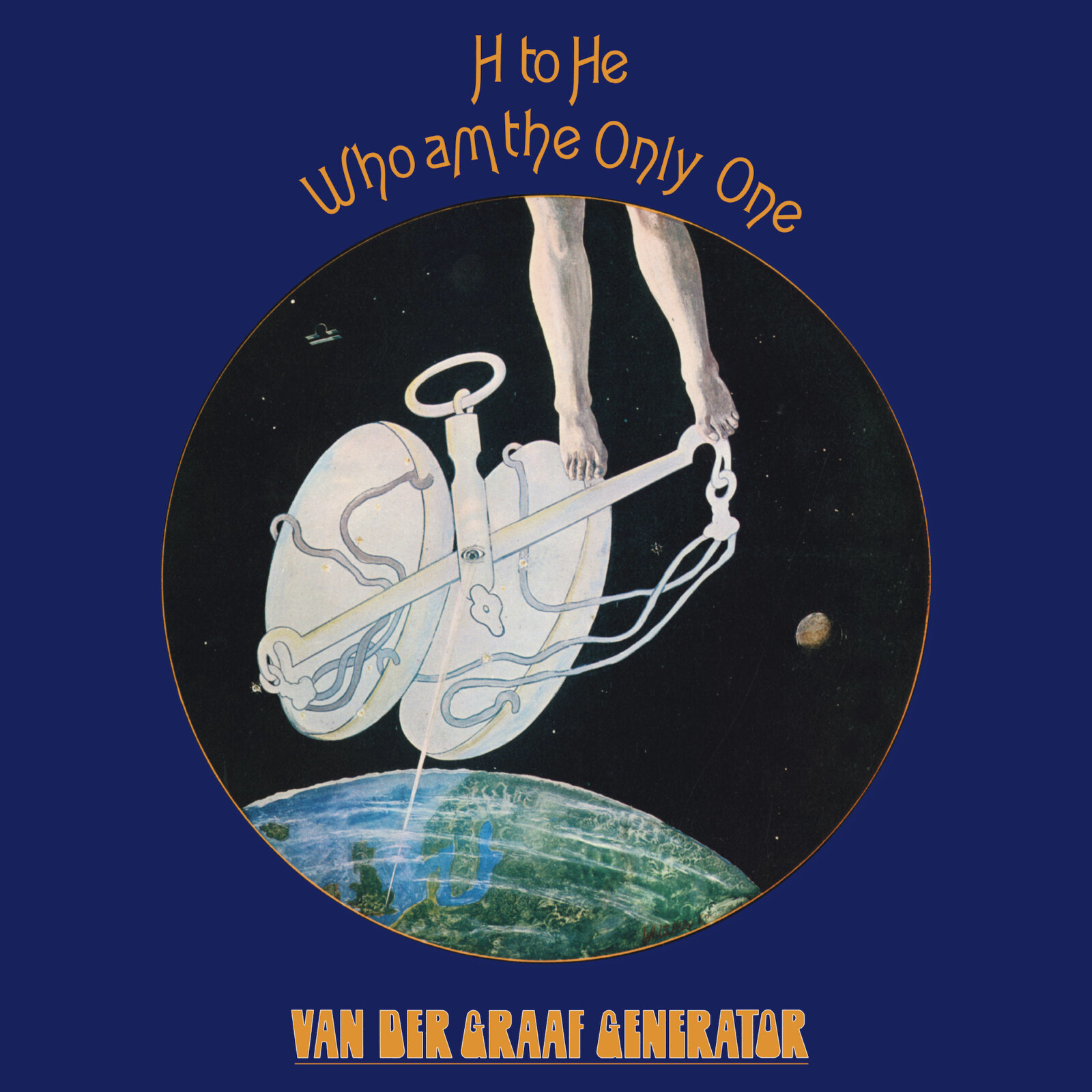

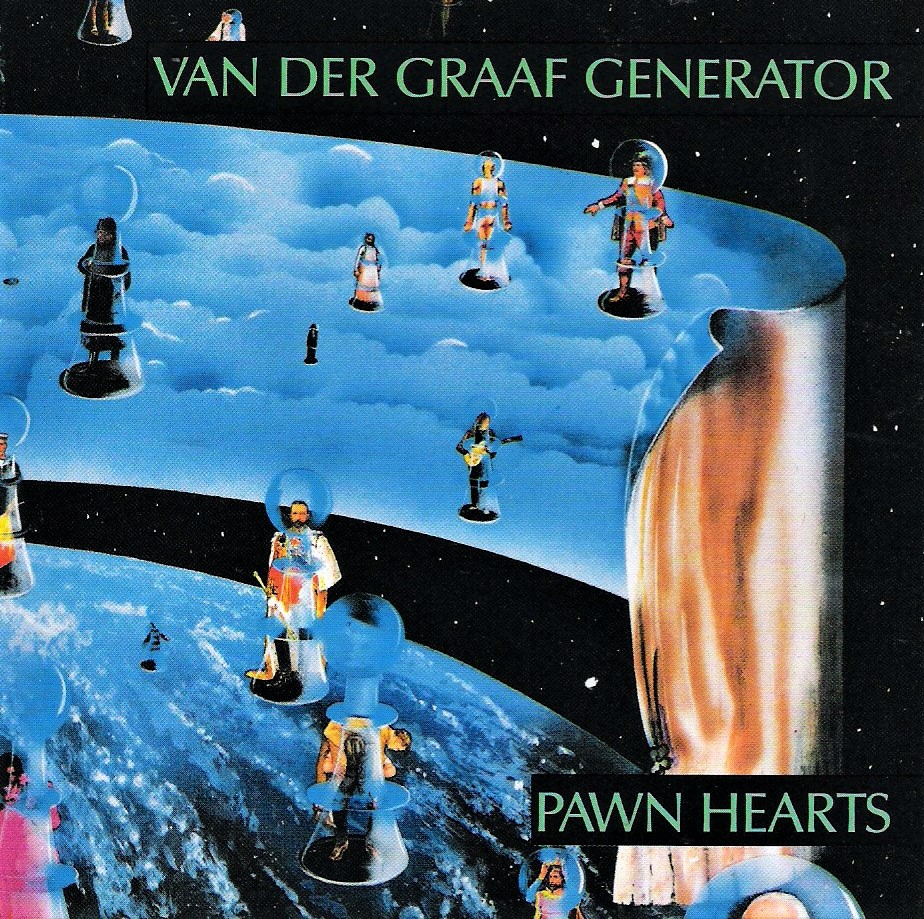

‘H To He Who Am The Only One’, ‘The Least We Can Do Is Wave to Each Other’, ‘Pawn Hearts’ are maybe among the most well known releases. It would be pretty impossible to go through the whole VDGG discography, but I would truly appreciate it if you can share some of the strongest memories from recording these three albums? Please share your recollections of the sessions.

It was a massively formative time for all of us. We were incredibly fortunate to be let loose in the most advanced, most experimental studio in London. Here we were, just kids really, super-keen to advance our craft , and bumping into people like Frank Zappa, and Mahavishnu Orchestra in the corridor.

Trident had a great attitude. If we proposed something unusual, the engineers were always up for it, viewing our outlandish ideas as challenges for their technical skills, or chances to experiment themselves. My composition ‘Angle Of Incidents’, (from the missing second half of ‘Pawn Hearts’) involved reversing the 2” 24-track tape eight times, and dropping glass neon tubes down the main stairwell, which had been rigged with very expensive microphones routed to every tape-delay in the building. It was a Saturday, and I’ve always wondered whether any prospective clients visited during this session!

The location was brilliant, right on Wardour St, just along from both The Ship (pub) and La Chasse (upstairs drinking club), where on any night, you could encounter many of London’s musician glitterati. It was also a stone’s throw from The Marquee, and a short walk to Charisma’s offices. Because Charisma was always looking to strike budget deals with Trident for it’s less famous acts, most of the music on those three albums was recorded at odd hours in discontinuous short bursts, when down-time became available. We’d come straight to the studio bleary-eyed from all-night drives down the M1 from gigs in The North. But there was always strong coffee and free sandwiches available round the corner at Charisma. There was really no need to ever go home.

Italy had a lot of great progressive rock bands. VDGG must be one of the most influential there?

We certainly gained a lot of very keen fans in Italy very quickly, and our popularity coincided with a time of extreme political upheaval that drew in many young people. I guess that combination of operatic, angular psychedelia with revolutionary fervor must have been a pretty heady brew. Strangely, I can’t recall ever seeing an Italian band that remotely resembled us, or showed any obvious VDGG influence.

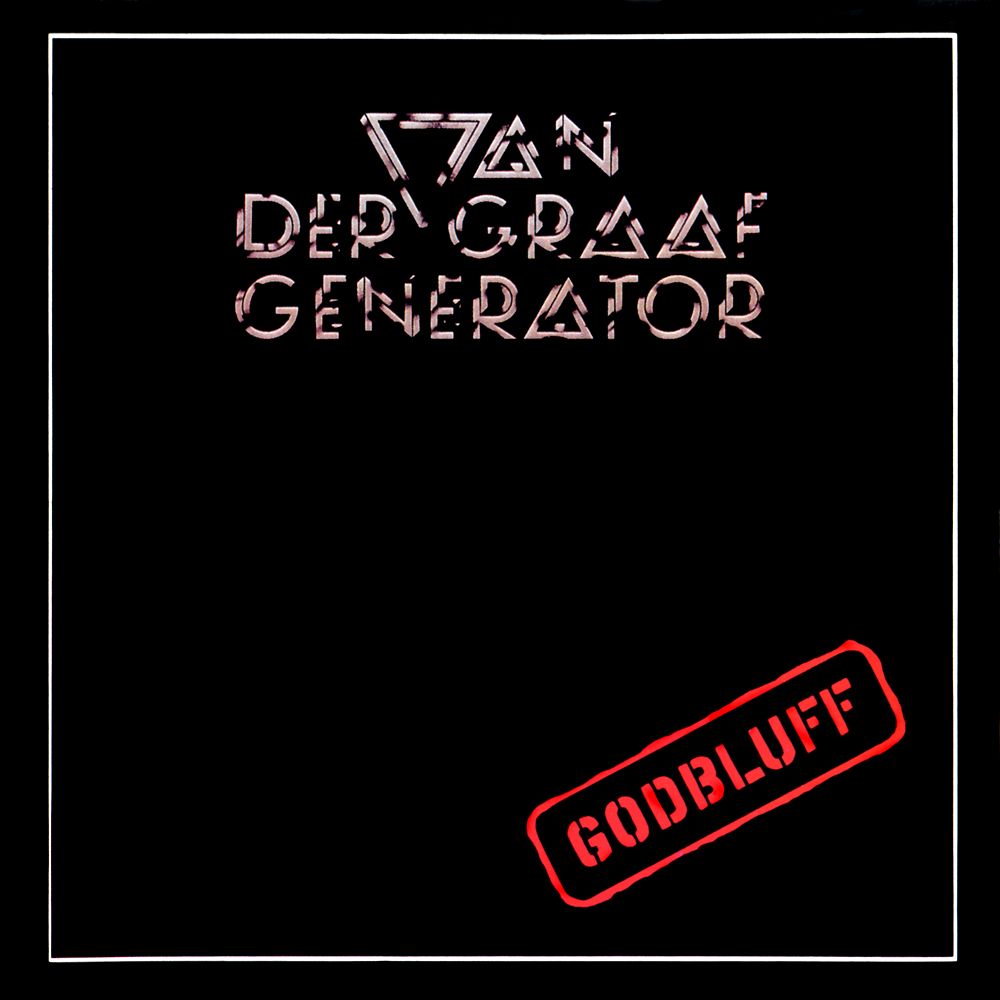

Was it difficult to get back together after disbanding for three years? ‘Goldbluff’ was a new chapter in the band. The sound changed quite a bit… your sound became more aggressive and raw. Was there a certain concept you were trying to achieve?

The only difficult part was negotiating a deal with Charisma to allow us the management independence that we sought, but which wouldn’t scare them off completely. We were young, arrogant, and thought we knew it all. Charisma believed in us but were hesitant to commit cash and effort to a future over which they would have much less control than they’d been used to. The whole thing took almost a year.

We’d all progressed a lot musically and wanted, at least for a while, to get away from elaborately produced studio creations, to concentrate on showcasing ourselves as a live unit – hence the more stripped down approach to recording ‘Godbluff’. We’d played it all live before we recorded a note.

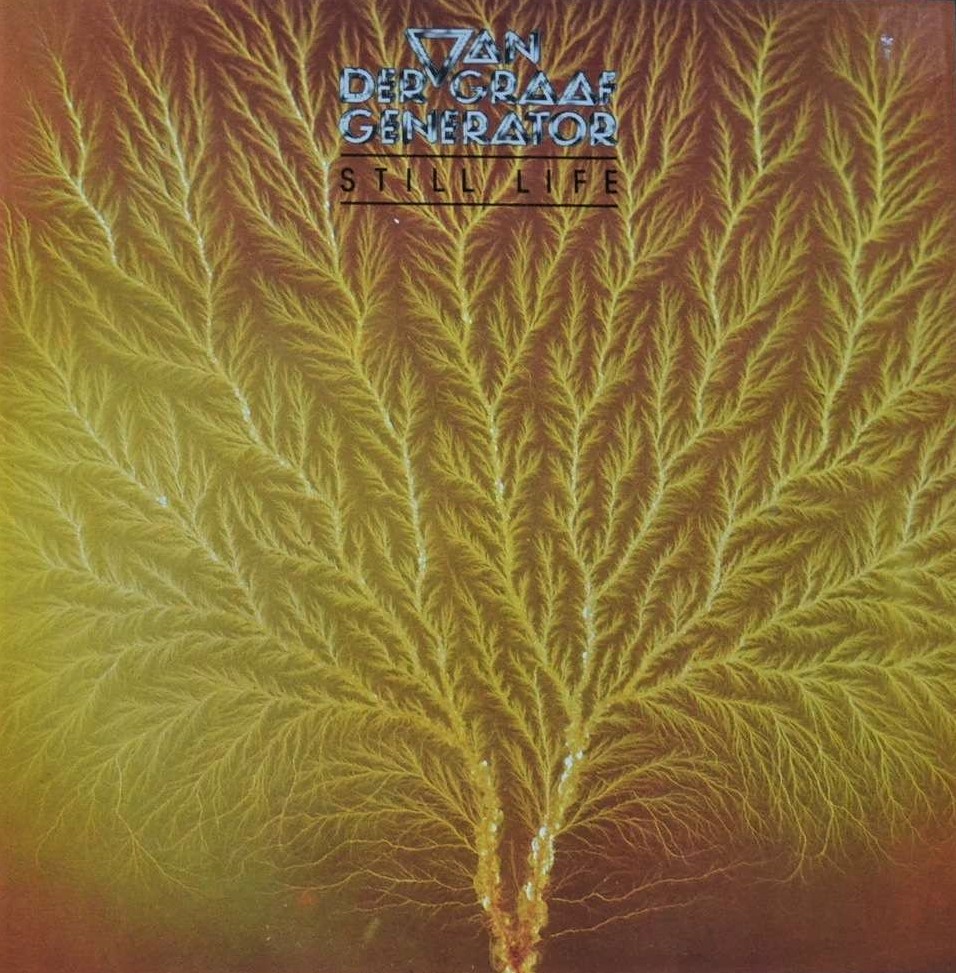

… the same approach continues on ‘Still Life’.

That’s not surprising, since both ‘Pilgrims’ and ‘La Rossa’ were recorded in the same sessions as ‘Godbluff’. There’s a noticeable drift towards more elaborate production in the later tracks (‘Still Life’ and ‘Childlike Faith In Childhood’s End’). This was partly down to the nature of the songs, and partly because we had become more familiar with the set-up at Rockfield.

What inspired you to become a drummer?

I guess it was expediency – and those armchairs, though maybe seeing Sonny Payne at close quarters when I was eight had something to do with it. Credit must also go to my prankster dad. I used to go to band rehearsals with him when I was a kid, and I’d always sneak a go on the kit before everything started. My dad would brief the trumpet section to join me onstage and play a brass stab as a section whenever I hit a particular drum. I quickly got a sense of just how much fun you can have from the drum chair.

When I formed a band with two friends (We called them ‘groups’ back then), there was no drummer, but my guitarist friend’s dad, Ted, had played drums in my parents’ big band. With a little pleading, I got Ted’s old kit and some great drumming tips. If I couldn’t figure out the part to the latest Shadows hit, Ted would show me. He was genuinely interested because he appreciated what a great drummer Tony Meehan was.

Would you like to comment on your drumming technique? Give us some insights on developing your technique.

I usually refrain from commenting too much on my technique, in case I get rumbled. I’m frequently referred to as a jazz drummer, which isn’t really the case, though I guess I must have absorbed some essence of jazz drumming through osmosis and early exposure. I do get a kick out of infiltrating the odd jazz line-up, but, in deference to the real guys, I have to say that I never did put in the hours or the study. In fact, I’m pretty bad with practice – too easily bored – usually preferring to immerse myself in fresh challenges and just play.

I’ve learned to turn this lack of discipline to my advantage, because I find significant new ways to play when I come back to the kit after a long lay off. My technique often gets really rusty. However, simply through no longer being able to execute them, I’m freed from my standard set of licks, and get a lot from experimenting and surprising myself.

However, I do panic a bit if I have a demanding stretch of work on the horizon, and try to be diligent about getting my hands and the rest of me in shape. Breathing and relaxation are important.

Aside from having a creative attitude to non-practice, I’d say my long-term maxims have always been, keep listening, keep learning, and try not to screw up.

Would it be possible for you to choose a few collaborations that still warm your heart?

I’d love a chance to play with Kazue Sawai again. Playing on her album, ‘Eye to Eye’ was a real privilege. I’ve been in Tokyo a couple of times in the last decade, but didn’t have time to look her up.

For the last forty years, I’ve been putting together a duo album with the alto sax and flute player Finn Peters. It would be nice to finally finish that, and maybe do some shows together. We first started recording in 1979 when Finn was a young child. Ernst Reisjeger, who I’d also like to play with, used to stay at the house that I shared with Finn’s parents. I did produce Ernst’s duo album with Sean Bergin, but we hardly did any playing together. Come to think of it, Finn and Ernst, now that would be some trio!

I recently found myself playing with Lou Edmonds on saz, at a mutual friend’s surprise birthday party. That one definitely had sparks, and I’d be excited to take it further.

When did you get familiar with Didier Malherbe?

My first experience of Didier was my induction, without warning or preparation, into the session band for his 1981 solo album ‘Bloom’. I’d driven to Ox’s Cross (at the time, Mother Gong’s UK base of operations) to rehearse for their headline appearance at Glastonbury. Harry Williamson had seen me playing with Life of Riley at The Festival of Fools in Barnstaple, and recruited me to play drums. He hadn’t mentioned anything about recording.

When I arrived at the house, I was straightaway hustled into the studio, without so much as a cup of coffee, because they only had around two hours of “smooth” power left (??!). I didn’t ask what that meant, because I had some fast learning to do, and the bass player turned out to be Hugh Hopper! I felt somewhat outgunned, because my physical efforts had recently gone into farm labouring, not drumming and my chops were in pretty crude shape.

Harry later explained that the studio was powered by a generator that charged some ex-army batteries. Four hours of generator delivering a wobbly, buzzy electricity supply while it ran, gave enough charge for two hours of “smooth” battery power. This turned out to be great for focusing the collective mind, and excellent for studio discipline. We recorded the whole album in two days.

Didier is, of course a fantastic musician, completely individual, always surprising, and great fun to work with. After ‘Bloom’, we worked together on two Mother Gong albums, and became friends.

You have known each other for so many years now. You also worked together on side projects, like for example your work with Peter Hammill or with David Jackson and Hugh Banton on ‘The Long Hello’. Would you describe your relationship with others in the band and what is the dynamic between songwriting and playing?

I’d describe it as brotherly affection, arising from longstanding improbable friendship. We’re all very different, and there’s always been the potential for conflict. Ben Watson has a theory that the best music involves musicians pulling in different directions, and that the much-vaunted pursuit of telepathic empathy is is over-rated, fated to produce boring results. I’m happy to report that, practiced as I may be at reading the signals of Peter Hammill’s elbows, or interpreting Hugh Banton’s merest eyebrow twitch, they are both capable of giving me plenty of panic-inducing WTF? moments that I cherish. I like to think I give as good as I get. Long may it continue like that!

The songwriting dynamic shifts around.. At one extreme, Peter presents us with sections or songs that are fully-formed, including lyrics. It’s then about learning the riffs/chords and rhythm changes. Once we have that sorted, we push and pull the song in whatever directions strike us as appropriate or interesting, then arrive at a consensus of what works. At the other extreme, we record jams, often based around half-formed riffs and sequences, then edit them into forms that work musically. Peter then goes away, devises vocal melody lines, and supplies lyrics. Apart from the odd amendment or correction, the lyrics are always Peter’s, though lately the initial idea for a song has on occasion come from an instrumentalist.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

I live in the hope that I don’t have to look backwards for that highlight! This continues to be an extraordinary adventure, but I can point to a few especially memorable shows.

There was one with the quartet in the amphitheatre in Arles in 1975, on the same bill as Archie Shepp. We somehow just had that special juju. The audience was with us from the first note. It was all quite wild, with bonfires burning at the back, and then our brilliant lighting guy, Rod, fired up a large laser that he’d found lying dormant behind the stage. It was very powerful and filled the amphitheatre with crazy lighting effects that were a complete surprise to us all. It sent the whole performance stratospheric. 2005 at WOMAD in Taormina had echoes of that one, and was also pretty fine.

2009 at The Montreal Jazz Festival is a personal favourite. We shared an evening with Ornette Coleman in The Theatre Maisonneuve (consecutive shows with different audiences). We were just getting to the end of what had thankfully been an excellent gig, when I looked over into the wings, and saw that Ornette was standing there clocking the band! It took considerable effort to maintain concentration. I had what competitive rowers call a “mind in boat” moment.

Back in the dressing room when we’d finished, I suddenly heard “that” sax sound very nearby. Ornette was warming up in the adjacent dressing room with the door open, so I walked out and stood there gawping like a sweaty stalker. Ornette stopped and said, “Can I help you?”, which is musician code for “should I call security?” I explained that I was just being a nerdy fan, at which point he poured me a glass of wine. Magic.

It’s impossible to pick out a favourite song, because our approach to them changes all the time. We rehearse diligently, paying close attention to arrangements, but when we get it right, performing always feels uniquely improvised. This makes the relative impact of any individual song unpredictable. The most tentative song in rehearsal might become the high point of the gig.

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

That’s tricky to pin down. There are those I’ve listened to and admired but whose technique I haven’t necessarily tried to assimilate, and then there are those I’ve consciously ripped off. In the latter category, I’d definitely place John Bonham and Tony Williams.

To my mind, Bonham at a stroke, elevated rock drumming into its own artform with that terrific economy, sound, power and swing. Before Bonham, if you wanted to establish your cred as a drummer, it paid to hint that proper jazz chops underpinned your rock playing. Ironically perhaps – because his jazz chops were actually pretty slick – JB made that obsolete. Suddenly it was all about absolutely nailing it rock-wise..

Tony Williams just seemed to assimilate all the most advanced rule books when he was a kid, then tear them up, leaving every other drummer in the dust. Every time I saw him, I just couldn’t work out how he could even conceive the stuff he was playing. It was really thanks to an obsession with his playing that I developed my patent technique of bluffing that I can play something with no idea of how to execute it, and just seeing what happens.

Probably the drummer most responsible for my early departure from orthodox technique was Elvin Jones. When he played with John Coltrane, drums were no longer just rhythmic foundation and structure, but became waves of energy. I still love that I can always tell it’s Elvin Jones from two seconds of ride cymbal.

I’ve also always been fascinated by drummers who retain a degree of rawness in their playing. I’m thinking Aynsley Dunbar with Frank Zappa, Jim Capaldi with Traffic and Ralph Molina with Crazy Horse (all players I stole stuff from), and in jazz, Jack DeJohnette.

It’s a crude categorization, but I divide drummers into technicians and magicians, and it’s the magicians that I really like (They can of course be both, but they quite often aren’t). In no particular order I’d mention Ed Blackwell, Ringo Starr, Ritchie Hayward, Danny Richmond, Mitch Mitchell as top spell-binders

Lately, I’m drawn towards players who are very otherworldly, and who create uniquely personal dimensions with their playing. In this category, I’d place Paul Motian and Tony Oxley.

I also really enjoy listening to younger players ( well, some are possibly under fifty!). In London, Seb Rochford, Tom Skinner, Richard Spaven and Leo Taylor, are all great in different ways.

Klemen Breznikar

Van der Graaf Generator Official Website / Facebook

Headline photo: Van der Graaf Generator ‘The Aerosol Grey Machine’ promotional photo | Credit: Cherry Red Records

All photo materials are copyrighted by their respective copyright owners, and are subject to use for INFORMATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY!

Nice to see the site feature another notable act particularly a cult legend like VDGG. Evans seems like an amiable guy who’s a pleasant raconteur in relating his experiences as an artist and the great time he was a part of.