Dave Atkinson | Interview

Dave Atkinson began writing in the late 1960’s, inspired, as were many others, by Bob Dylan who proved that you did not need to be a great singer, great guitarist or have an electric band to write a great song. Since then, he have come up with more than 400 songs.

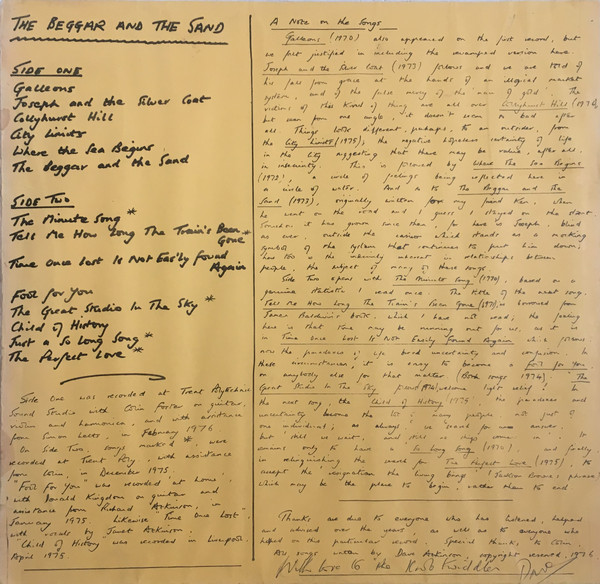

In the 1970’s new influences made their mark – English traditional song, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and Kris Kristofferson. The early imitative Americana was replaced by something that became more distinctively an ‘Atkinsong’ and many of those 1970’s songs have endured to become staples of his repertoire today. Dave Atkinson produced two limited run vinyl albums, ‘Atkinsongs’ (1973) and ‘The Beggar and The Sand’ (1976).

“There is nothing like that first burst of inspiration”

Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life? When did you begin playing music?

Dave Atkinson: There was always music in our house, from Mum, and after her my sister Janet. Both had lovely singing voices and played the piano beautifully. Mum’s father, Edgar Newbury, had been a singer and a thespian, a performer in Gilbert and Sullivan Operas. Perhaps I got it from them, whether by example and encouragement or genetics or a bit of both, I do not know. No doubt the musicals Mum and Dad loved, and the richness of 1960’s pop, fed into my sub-consciousness. Hearing Bob Dylan for the first time persuaded me that making up and singing a song was something that even I could do. Of one of my early tunes, I remember Mum saying: “that’s the sort of tune the milkman sings.” It was the first line of one of the great stories of my life, telling me that I had song to sing.

Who were your major influences?

Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne, Kris Kristofferson. More recently, Steve Knightley of English Folk Band, Show of Hands.

Did the local music scene influence you or inspire you to play music?

Not particularly. I “worked” in isolation a lot of the time, not beginning to “perform” much until the early 1970’s and then mainly informal sing-round type things with “mountain” friends which relied on a few staples of my own songs and lots of covers. This is still my main “audience” today.

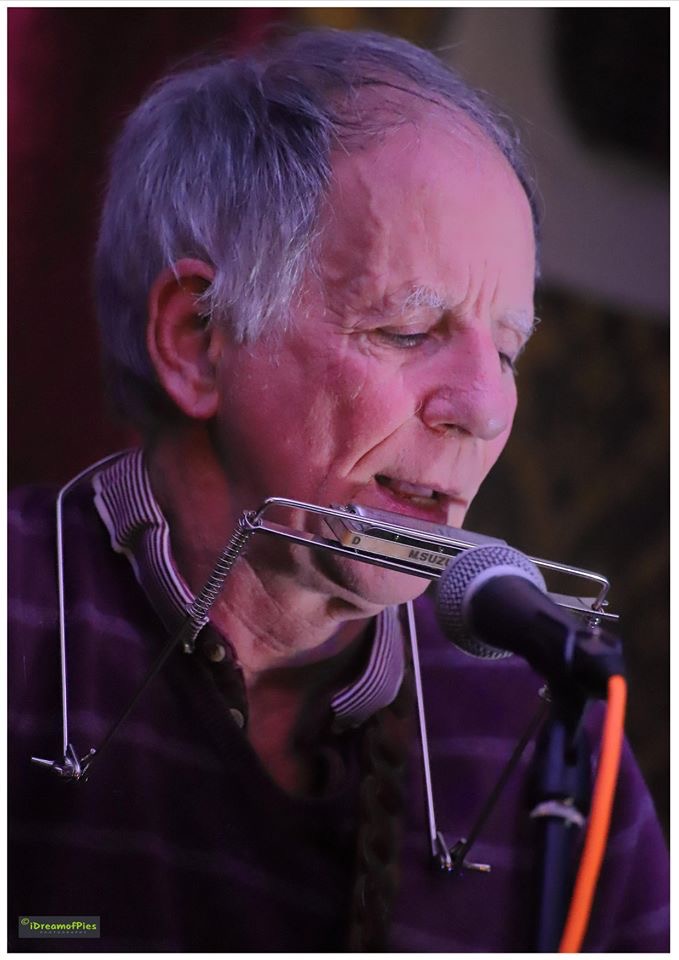

‘The Last House in Erskine Street’ which was on ‘Atkinsongs’, has been a significant song for me. It has been “covered” half a dozen times – though always by my mate Ken! Not long after the song came along, I performed it at a folk club run by the Spinners folk group at the Gregson’s Well pub on Low Hill in Liverpool, just up the hill from the Street. Mick Groves, who I saw as the “leader” of the group, asked me for a tape of the song. I thought my “moment” had come, but nothing came of it, though I think the song might have suited them well. In a gesture of great kindness, Spinner Cliff Hall gave me a D major harmonica which I treasure to this day. Forty-five years later, in 2018, I sang the song at a meeting of Chester U3A, to an audience of over 70 people. Many people had seen the David Olusoga TV documentary “A House in Time” and were able to relate to the story of the song. Several came up and shared their own memories of Liverpool in the 1960’s and 1970’s. ‘The Last House in Erskine Street’ is that kind of song.

In the last 9 years or so I have given up the isolation and been a member of Chester Songwriters Group and have performed at assorted open mic and folk festival sing-rounds. I enjoy all of these, learning how to judge the crowd and pick the songs to suit. All my years at the informal sing-rounds have given me a good stock of “covers”. I hear lots of things I love, and also plenty that tells me how not to do it, that’s important too. I am 70 now, but the guitar playing is still good enough, the singing voice in great shape, hopefully when the current COVID thing has passed I have more of this fun to look forward to.

Were you part of any bands?

I was briefly a part of band in Liverpool, in the 1970’s. We were called the Silver Dufflecoats. Never really been able to, or wanted to, make the kind of personal commitments needed for a band.

What was the first song you ever composed?

Number 1 in my songbook is a thing called ‘Cathy Come Home’, it was based on the BBC Play for Today of that name credited with leading to the founding of Homeless Charity Shelter. I have never “performed” it, but there it is. It was 20 or so songs in, when I was 18, before I came up with the songs that still sound good today. A selection from the first 130 or so went on to 2 one-off vinyl albums. Forty years later the best of these were “rescued” and ended up on a well-received new vinyl, ‘First Take’. The earliest of ‘The Beggar and the Sand’ songs was opener ‘Galleons’ at number 140.

What are some of your strongest memories from recording ‘Atkinsongs’ back in 1973? The songs were already a couple of years old at the time.

I had an Akai reel-to-reel tape recorder with twin microphones. There are some copies of the LP dated 1973 so probably the recordings were done that year. It was all done “at home”, home being my parents’ home in Hampshire. My sister Janet, 14 years younger than me, features on a couple of songs – vocal and recorder; she was just 8 or 9 years old then. Her friend Sarah is on one of those too. The thing for me is that all the songs on that album have proved to be “keepers”, one I might need half an hour or so to work up, but the rest I could do straight away, remember all the words too. I guess that’s because I’ve carried on performing them ever since, and have some fancy digital recordings of some from more recent times.

Was it privately released? How many copies were made?

Yes, released privately, I just got a 100 copies done. Sold most to friends, family, et cetera for £2 each. I sent the tape off to an outfit called Menlo in Dublin. Much later I learned that the actual pressing was done by Deroy, based in Cumbria. All their pressings have a catalogue # and some are very valuable.

How about ‘The Beggar and the Sand’? What’s the story behind it?

In a way it was the realisation of something that began with ‘Atkinsongs’, the realisation being the addition a really accomplished, musicians (Colin Foster on guitar, violin, harmonica) and the opportunity to use a proper Recording Studio. All the tracks came from the same early 1970’s pool that the ‘Atkinsongs’ material came from, and only 6 of 14 were written after that album was recorded. One song, ‘Galleons’ was also on ‘Atkinsongs’, that I now regret, should have kept it for ‘The Beggar and the Sand’. Spent many years since catching up with dozens of songs any one of which might have been just right for that slot on ‘Atkinsongs’.

What is the song-writing process like?

I think for the first 30 years or so the process was largely instinctive. Now, despite being more “knowing” about it, having more “experience”, I do not believe what I have come up with since is any “better”. There is something about being in your twenties, and all the stuff that goes in a life then – growing up, finding love, settling down, and so on – and the raw experience of it all, that just does not happen later in life. Thinking of my “go to” songwriters – Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne, Kris Kristofferson – and I think the stuff they all did in their 20’s was at least as good as anything later. To a degree I suppose when I first heard their songs I was in my late teens/twenties and you just experience stuff more intensely when you are at that age.

Despite all that I now have a way of articulating how it works for me. Probably that took shape during the 1990’s when I had a songless decade. I got used to it, life was full enough with young children and with 300 songs in the bag I did not really need more. As well as enabling me to come up with half-decent answers to questions like this one, I derived a few “lessons” which work for me:

– Don’t go looking for the song, let it come to you, it will do that when you, when it, are both ready.

– If you find yourself struggling with a song, leave it, it might come back in another form that works first time.

– You should be getting the basic thing in place within an hour or so, then keep singing it, tweaking it, testing it, over 2 or 3 weeks until you really know it inside out, have cut the baggage, exploited it for all its potential.

– If you are short of song, go to the physical, mental, emotional place where they can “find” you:

Poetry and hums aren’t things that you get, they are things that get you. All you can do is go where they can find you. (Winnie-the-Pooh) I found myself in the “place” recently recuperating after surgery in hospital. Happily able to go for many months with nothing I got “assaulted” (it felt like) by 4 songs in 5 days. Still dusting myself off after that, and in the shake-down I suspect there are a couple of keepers.

“Making up a song is a simple thing.”

All the above means that I am rubbish at writing to a theme, competition topic, et cetera, either I’ve got something to fit the brief or I haven’t.

But now, for what it may or may not be worth, here are my thoughts about how the process works for me:

Making up a song is a simple thing. Everyone must have a song in them. But for some people that simple thing becomes a pastime, even a passion, and for a few, of which I am not one, a money-earner. It is not like, say, visual art, where real skill in handling and using materials is essential if the artist is to realise his or her vision on a one-dimensional canvas. The song-maker simply has to find a bunch of words and a selection of notes, and there it is, done. But, after losing 50 years of skin in the game, I am conscious of having some skills, having a craft. When you sing your own songs, the basics are words you remember, a tune you can sing, and accompaniment you can play. Avoid “completism”, leave gaps so listeners can find their own way into, make their own sense of, your song, plus chorus and hook sign-posts so they don’t get lost. Provoke, stir, beware bland, avoid the “clashing consonant” trap where the first t goes shy as in can’t tell or can’t take. Alliteration can be good, perhaps propelled by an internal rhyme as in “don’t bury all the mem’ry in the mourning” which has added joy in “mourning” which could also be “morning“. Rhyme and structure are good but can cage a song, sometimes be ready to let it fly free. A verse-end line can do extra work for you, such as “put your hands together for me“: it’s applause, coming together, and prayer. Simple is often best. You need lyric phrase to match melody one, words that sound right for the “tone” of a song. If you must write a “love” song, remember it’s not just about needy, heartbroken, awesome you. Give the other party active agency not just objective passivity. Remember that a song is more for your listeners than for you: entertain, engage, don’t just show off. What wows one audience will bomb with another.

I refer to this conscious element of the song-making me as “the Editor”. He has to be constantly vigilant in relation to the other member of “the team”, the “Mischievous Muse” who comes up with the ideas, the inspiration. Muse is a distant relative of the Greek muses who are Goddesses of the various arts such as music, dance and poetry. Not only had they fine talents, but also, apparently, beauty, grace and allure, inspiring musicians and writers to ever greater artistic and creative heights. Sadly, my own Muse, a scurrilous individual determined to present my festering faults to unsuspecting listeners, has no redeeming features, Allure not required. He has none.

For me the clue is in the word “inspire”, sharing as it does a common root with “spiritual”. Writing about religion, Ninian Smart finds the human instinct for faith analogous to, and as universal as, the instinct for music. Perhaps they are not two things, but one thing expressed in different ways. A Christian Priest said of her faith: “I‘ve found something life-giving and good, it just wells up inside me and I want to share it with other people.” That just nails for me the experience of a new song taking shape. Beth Nilsson Chapman takes the flow a little further: “There is nothing like that first burst of inspiration, starting a new song, diving into the current of the creative flow before I even know what I’m writing about. I just follow the song because it always knows where it is going.” Perhaps Muse, not knowing, Editorial, me, knows best after all.

Was there a certain concept behind ‘The Beggar and the Sand’?

As I remember it, I deliberately “bookended” it with “love” songs, giving contrasting perspectives on “love”. The opener ‘Galleons’ from 1970, is the big heartbreak anthem, of its type never excelled or imitated anywhere in my 440-song canon. Underlying it I suppose is the idea that there is such thing as a perfect love, which is debunked in the closing track. Otherwise I do not think I stuck to the concept. There was a bit of “clever clogs” stuff, Track 4 is a sort of counterpoint to ‘Galleons’, “sampling” its chord progression, ‘Galleons’ ends with ships in port sheltering from a storm, T4 ‘Where The Sea Begins’ ends with “my sails are set and I wait for the wind“. Answer continues below…

Would you share your insight on the albums’ tracks?

The original vinyl listed 14 separate tracks. Indicates 2 songs joined to make a continuous musical track.

‘Galleons’

This came along after being dumped by first girlfriend. It was a big deal at the time but the “Let’s not say we lost” chorus lifted me out of the sadness. I have 3 recorded versions, there is a terrific cover by Yvet van der Tuin but this one, with Colin’s violin and a spot-on performance by me is the definitive recording.

‘Joseph and the Silver Coat’

Another spot-on performance, Colin’s guitar, my vocal. The song is an allegory of the “get rich quick” fallacy, complete with nod to the Biblical namesake. The “is it rolling Bob?” was heard on Dylan’s ‘Nashville Skyline’, the Bob being producer Bob Johnston. Clearly it was or it would not be in my song! It is now the title of “Dylan Reggae Tribute” album.

‘Collyhurst Hill’/’City Limits’

Perhaps the stand-out track, it combines 2 songs with a Northern City theme, juxtaposing the uncertainty experienced by the spurned “I” in ‘City Limits’ with the desolate certainty of another character in the same song and pretty much everyone in prospect-less ‘Collyhurst Hill’. This one juxtaposes all that with a jaunty tune and a feisty fightback. It is from after I went back to Manchester in 1975, everything else apart from ‘Galleons’ is from when I lived in Liverpool, so it sort of does not belong here. It turned up late one night and was boxed off in 20 minutes, complete with key change bridge and use of the sub-tonic C in place of the dominant A, borrowed from Dylan’s ‘Blood on the Tracks’. ‘City Limits’ is almost a “nothing” song but here it shines all the way to a cold “nobody stops to ask why” of the final verse. Recorded in one or maybe two takes, the change from the bouncy Common time of ‘Collyhurst Hill’ to the elegant waltz of ‘City Limits’ is perfectly executed. Colin and I got through to the last few bars before there was a hiccup, that’s on the original vinyl, fixed on the CD and the vinyl re-issue. The playing throughout is fine, Colin’s violin is as good as ‘Galleons’ gives us reason to expect and good-enough flat-picked guitar from me.

‘Where the Sea Begins’

This was Colin’s favourite and his lovely guitar playing enhances it beautifully. What I now know as the D11, C, G Chord succession was shown to me when I was living in Kirkby, by a young lady who was fellow-volunteer at the youth club I worked at 1971-2. The water-cycle is used a metaphor for the grief and recovery process.

‘The Beggar and the Sand’

The closing track of Side One of the original vinyl. It goes back to 1972 when my mate Ken went “on the road”, unsettling for more cautious conventional me in all sorts of ways. I was starting work in Social Services, and the Beggar stands for the “less fortunate”; he was a real person who haunted the queue for the bingo hall every evening. The Sand is the instability of relationships when you take up roots and go roaming. It is quite demanding for the listener so it is saved for special occasions such as Ken’s 65th birthday party when it was just awesome.

‘The Minute Song’/’Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone’

‘The Minute Song’ is, as the name suggests, brief, and it leads straight into ‘Tell Me How Long the Train’s Begun’, title borrowed from James Baldwin’s novel. Ken was very aware of the environmental disaster awaiting the planet and in his early 20’s might have been surprised to get to his 70’s and the planet still being saveable, that the train has not yet gone. Of all the songs on the album, it is perhaps the stand-out one, and the one thing from ‘BATS’ [‘The Beggar and the Sand’] that shows up on the internet as a single song.

‘Time Once Lost is not Easily Found Again’

This one would be dull fare without my sister Janet’s lovely backing vocal and the final verse twist that has everything losing its bearings and leaves nothing resolved. A home recording.

‘Fool for You’

Jaunty pop with a sweet chord sequence and great guitar from my brother’s mate Donald Kingdom who used a cardboard plectrum for the exit arpeggio. You can sense him nailing it better as the song goes on. Brother Rich was on the controls. Home recording. There is digital re-take of this on Spotify, equally fine, even perhaps the edge.

‘The Great Studio in the Sky’

Witty crowd-pleaser playing games with art and reality and then collapsing when confronted with abstract art. Probably “unmixed” studio recording which does not really need the sung intro.

‘Child of History’

Awesome sweep of a song that encapsulates British history in 4 verses. It is a particular take on history, a broadly “left” one, and some mighty imagery in the first verse and then again in the last, where the unfulfilled promises of the ships that don’t come in are as true today as ever. The digital re-take on the ‘BATS’ CD re-issue is better.

‘Just a So long Song’/’The Perfect Love’

Just a ‘So long Song’ is a bit of surplus baggage, followed by ‘The Perfect Love’ which debunks the idea that there can be any such thing. I had 30 years or so feeling a bit embarrassed about it, sorry that I put it on the album. Now I think it as fine as any “love” song. What it has is just enough of that acknowledging that the outcome, the feeling, owes at least something to the other party. In this case, “Of all the things I have lost, somehow you don’t remind me/You just make me glad to have what I’ve got“. Another example is Dylan’s ‘Make Me Feel My Love’ which would a pretty terrible song (for me) but for “I know you haven’t made your mind up yet“.

What influenced your sound?

The biggest factor was having access to a “proper” recording studio, at the then Nottingham Polytechnic, thanks to my friend Colin, who acted as the Producer, assisted by our friend Simon who did “knob twiddling” as required (e.g. when Colin was playing). We had 2 sessions (late 1975, early 1976) in one of which the bit known as the “mixing desk” did not work, meaning that the character of the sound is uneven, made more so by the 3 songs recorded on the Akai reel-to-reel “at home”. Also, the pressing was not great, Colin who had a proper musician’s ear, complained that everything sounded slightly “flat”. Sadly Menlo (the provider) did not return the original tape to me and the copy I had at home disappeared in a burglary.

In 2011, 35 years after the album was recorded, I began to receive unsolicited enquiries from various parts of the world about ‘The Beggar and the Sand’ and ‘Atkinsongs’. Sadly, I was not smart enough to think that something like this does not come from nothing. I let half a dozen go to a lady in South Korea before getting an enquiry from a chap in Florida, USA. He asked if I had a good original copy of ‘BATS’, sadly I did not, “well I have”, he said, and in an act of great kindness sent me the audio. I was able to use this to issue a “40th anniversary CD”, funded by the cash raised by the sales to the South Korean lady. With the kit and skills I now have, I was able to clean up the audio and re-sample it to fix the “sounding slightly flat” issue.

When a “collector” from Italy contacted me, all I had left was a not-so-good copy of ‘Atkinsongs’. I decided to try the approach I should have used with the South Korean lady: make me an offer. I was amazed when the offer was £150! It was only then that I realised that ‘BATS’ and ‘AS’ had value as “rare vinyl”. Since then, friends have returned copies to me, those have gone to the collector and it has generated over £2000 – £1500 of it passed on to various “good causes” with some used for “overheads” (website, et cetera) and to underwrite the cost of 5 new vinyl LP’s based on old reel-to-reel tapes recovered from the loft at home. These tapes include some “out-takes” from the original studio recordings, some of them excellent. I do not know if my Collector’s investment was profitable, I hope so, he made a huge difference to me, also encouraging me to take that trip up to the loft, assuring me of his backing when it came to buying the resultant LP’s which with a short-run pressing work out at £40- £50 each. I have seen ‘BATS’ change hands for £400 plus and I still have 2 each of ‘AS’ and ‘BATS’, which I will give to my daughters. Both are currently listed on Amazon at 650USD. It seems that whatever it all was has passed now, no recent enquiries, but I still ship the occasional CD.

One final delight of what has been a wonderful adventure was that I was motivated to get in touch with Colin again, now working as a sculptor in Hungary – a very successful one too, he has international standing.

What, if anything, would you like to have been different from the finished product?

On the original LP there were a couple of bits I would drop – the penultimate short (lasted less than one minute) song added nothing and one track had a “sung intro” which added nothing. Otherwise, all the songs and recordings are “keepers”.

Did you do any gigs?

Very occasionally. Once a year at best. Maybe I do not graft at it enough, or just not good enough at “performing”. Besides the songs, the performing itself is a real “art” one I am still learning – from “open mic” sessions locally, sing-rounds at folk festivals, night around the stove in my Climbing Club Hut in Snowdonia – most important, it’s different strokes for different folks, you are there for the people who are good enough to listen to you, want sing your choruses, so entertain, engage, don’t try to show what a genius you are.

Which songs are you most proud of?

Where to begin? Let’s start by saying I’m proud of the “body of work”. Pretty much whatever the Chester Songwriters Theme, I’ll have a song or 2 for it. When approached by Spellbound of Greek Internet Radio Station Lost in Tyme, and given 2 hours to myself in November 2019,I picked 7 themes, divided them among 28 songs, and did the same again in November 2020, 7 new themes, 28 different songs. I have enough “in the can” to do the same again in November 2021. It is not just the songs, but also curating recordings made over the last 50 years, very few of them studio recordings, many not heard for 40 years or more, and developing the skills to make the best of them.

I am proud of my mountain songs which have brought more joy to others than anything else in my canon. I am pleased that I have figured out that these don’t work with the typical open mic crowd, but now I have a bunch of “go to” songs for that too. Among these are songs about song writing and performing, the one the begins “I play without technique or application and includes Meanwhile my instrument collection grows by the day/While I spend the kids’ inheritance on things I cannot play” does what an average performer like me has to do: meet the audience on their terms.

Finally, I have a collection of half dozen or so songs from the 1970’s about childhood ending and “growing up”. These are near to unique, and not for everyone, every time. Among them is ‘The Cradle’, which was on the ‘Atkinsongs’ album. A later recording is on my website with a slide show I put together for my 70th birthday. ‘The Cradle’ is something I could not “write” if I tried to now. It is based on a simple repeated G/Em/C/D chord progression and the melody/verse is draped loosely onto it like a tent canvas draped over a frame so that bits of the frame still show through the canvas. Things like verses, rhymes are there but not obvious. When my time is up, this should be the song, it won’t be the first time it’s been used in that setting. Some songwriters might want to erect that tent properly, now, “knowing” me might want to do that, in doing so the song would be destroyed as surely as ripping a head from a flower.

Is there any unreleased material?

Tricky one for me, this. I have over 200 songs recorded, about around 160 of those “issued” on 18 albums in vinyl and/or CD format. So, all those are “released” and available, some “from stock”, the rest “on request”. I probably have a couple of more albums in me, not yet recorded, one “old” material, the other more recent things. CD issues are usually runs of 10 or 20, sold to cover cost at £5 each.

What currently occupies your life?

My main project is a book. The basis of this is that I use around 20 of the songs to launch into topics that interest me, covering a range of things including art, war, history, faith and geology. It is called Golden Threads, being a series of stand-alone essays linked together by the Threads. I have included my own line drawings. One of the reason for the for the “full” response in this interview is that some bits from the book have been used here and content some developed here will be used in the book.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thank you for giving me a chance to talk about ‘Atkinsongs’ and ‘The Beggar and the Sand’. I know I have talked up ‘BATS’ a lot but I think its story as much as the result justify that. I am very grateful to all the people who have supported my music over the years, including yourself, now Klemen. “A song without a listener” is indeed “a sail without a wind“. Dave Atkinson

Klemen Breznikar

Dave Atkinson Official Website