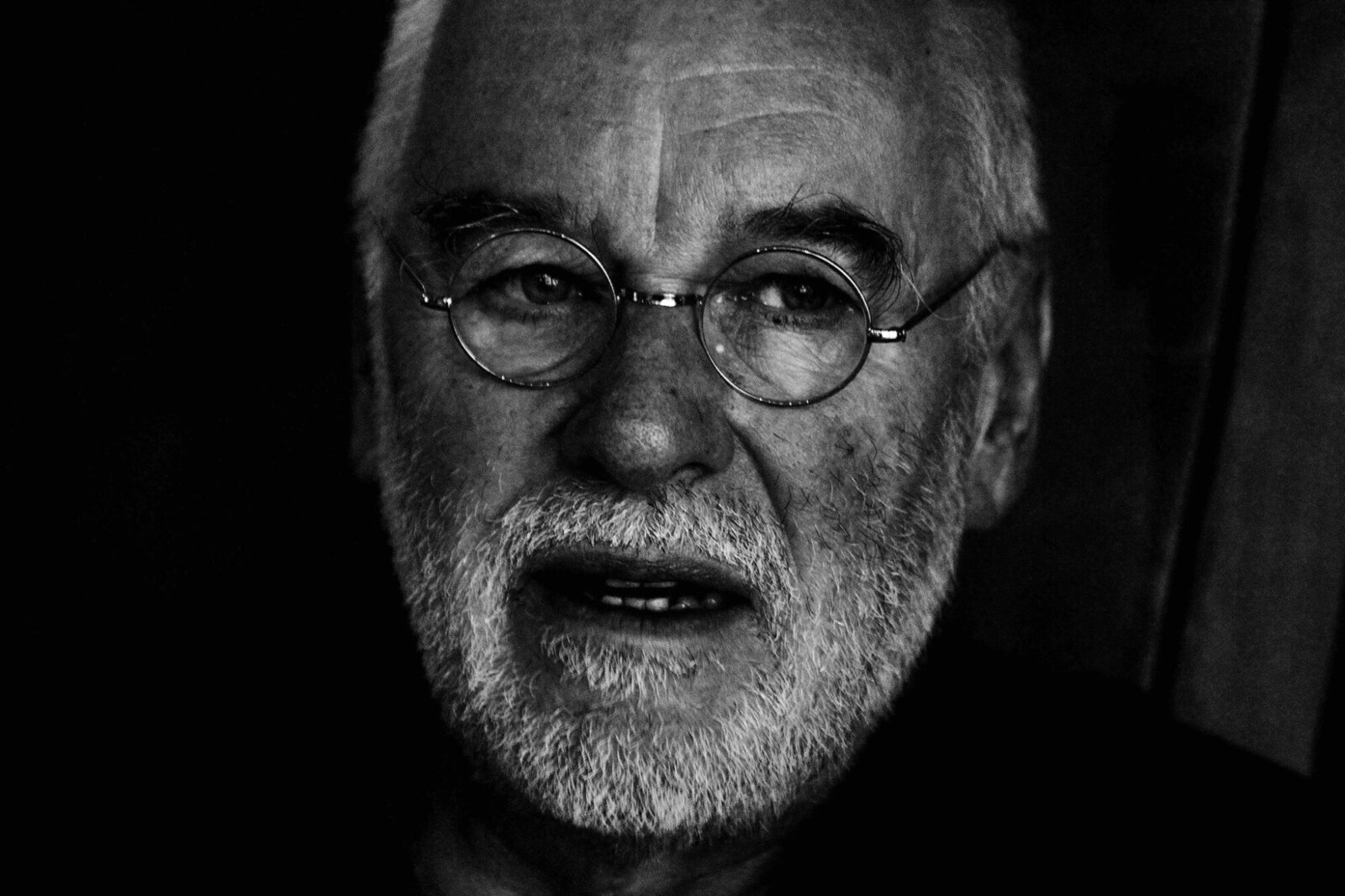

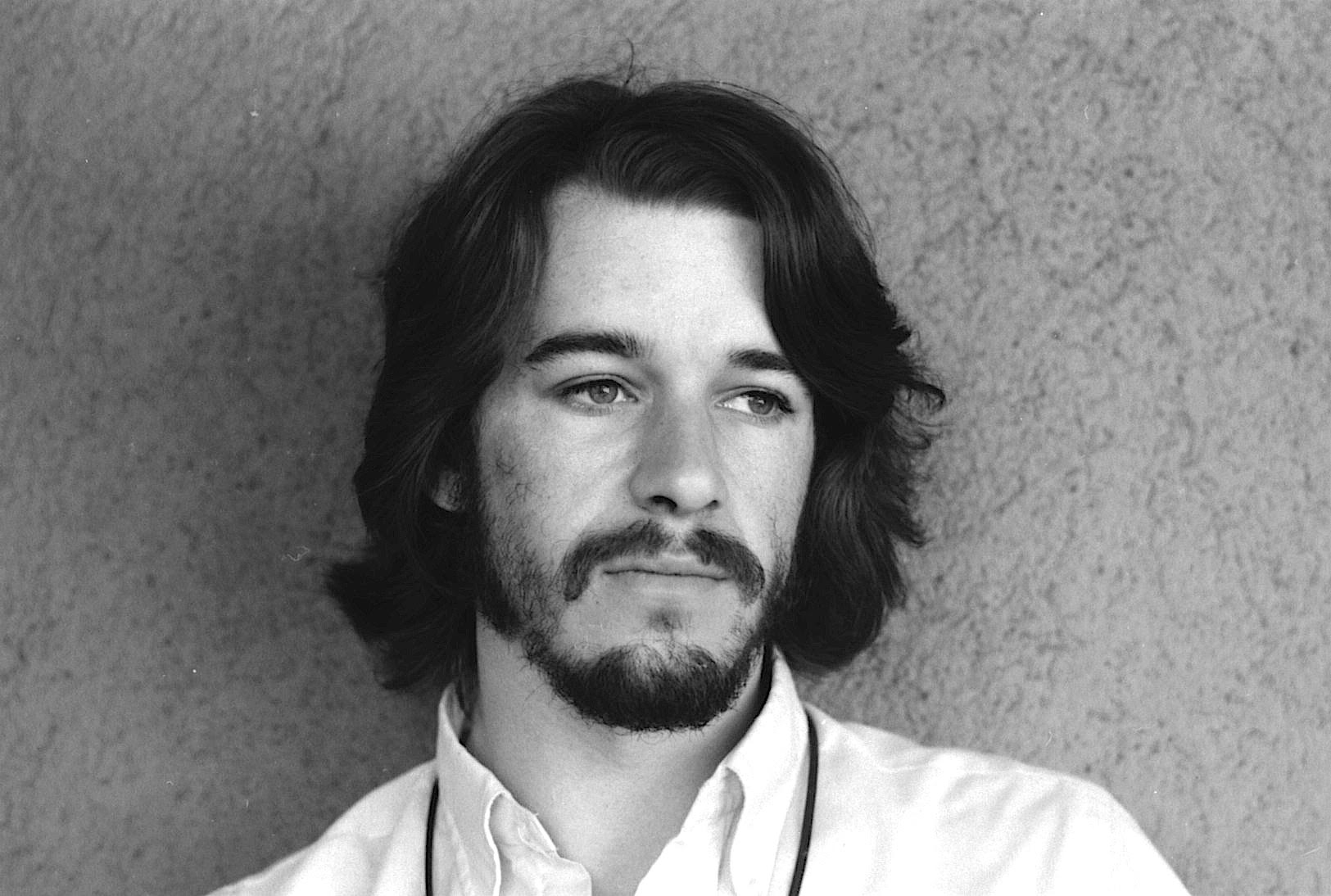

Richard Palmer-James Interview | Supertramp, King Crimson …

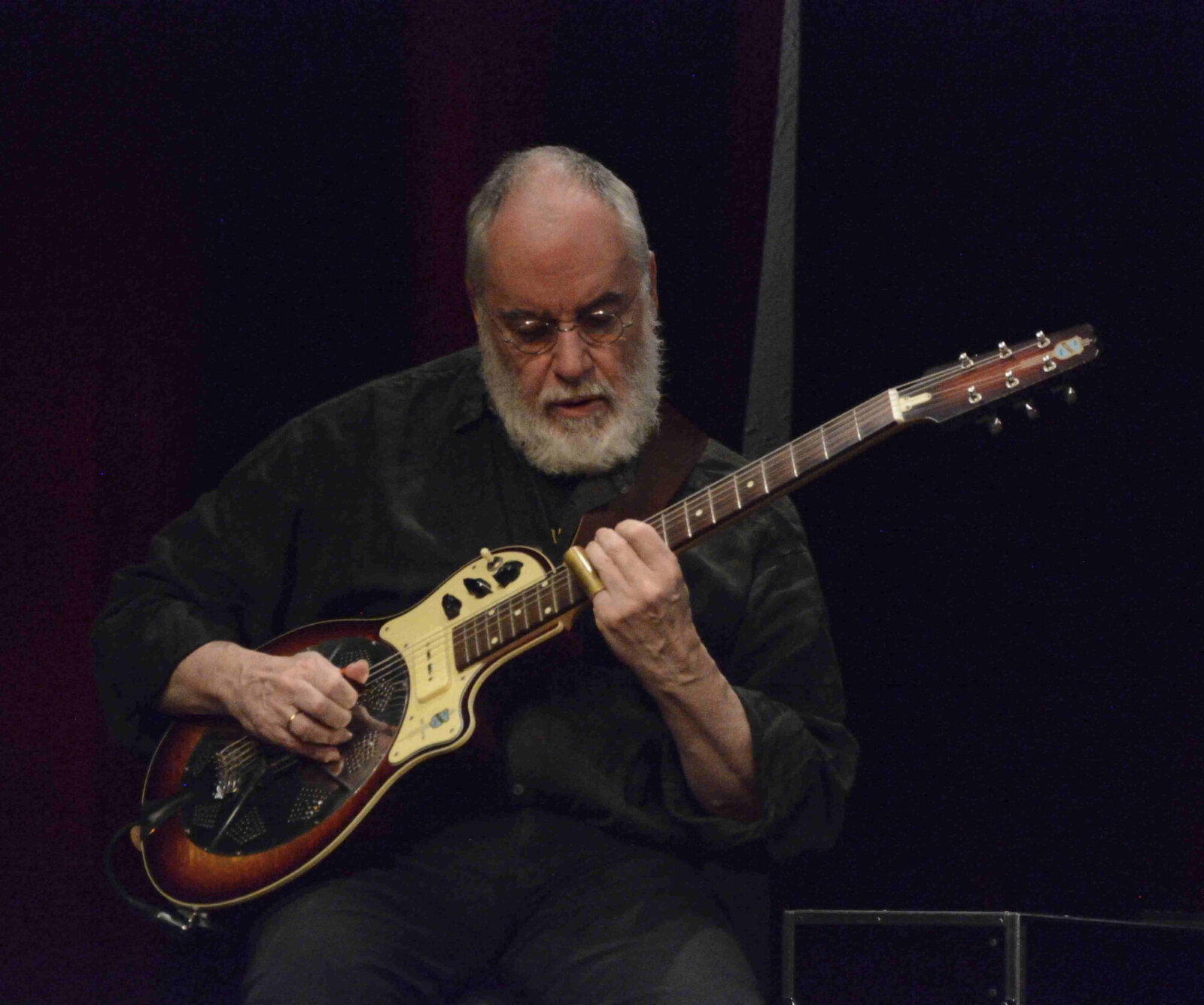

Legendary musician Richard Palmer-James is credited on more than 500 recordings. He’s best known for being one of the founder members of Supertramp and for writing lyrics for several songs by the progressive rock group King Crimson in the early 1970s. Palmer lives in Munich since the early 1970s and is still very active.

What were your first musical involvements?

Richard Palmer-James: When I was a boy in the 50s, we didn’t have a record-player or any musical instruments at home, but the radio was on all day. I enjoyed the classic pop and dance band music, learning the words if I could, sometimes imagining myself to be the artist – there was no way I could visualise Sinatra, or Bing Crosby, or Nat King Cole, but some of their songs seemed to suggest a world-weary wisdom that was intriguing. Around 1960, when I was 13, I started picking out tunes on a ukelele, and my parents bought me a guitar. Like other kids at school, I learned to play the instrumental hits by The Shadows, The Ventures, Duane Eddy, et al. This was an excellent way to learn basic guitar skills, and it undoubtedly kicked off the careers of many, many musicians in my generation. The first tune I could play all the way through was ‘Ghost Riders In The Sky’ by the Ramrods. The first tune I played in ensemble with others was ‘FBI’ by The Shadows.

I come from Bournemouth on England’s south coast. Robert Fripp, the Giles brothers, Greg Lake, Andy Summers, Gordon Haskell, Lee Kerslake, Zoot Money, Al Stewart, and of course John Wetton, all grew up in this area. (’To name but a few’.)

“The 60s was a long series of musical revelations, boundaries expanded and crossed, risks taken.”

Who were your major influences?

As the 60s continued, Britain was increasingly exposed to Black music, and I tried to emulate the great blues players without really understanding the visceral musical experience that had informed their stylings. I didn’t realise until much later that it’s the emotional background of their music, and sometimes their use of the guitar as shorthand for an entire orchestra, which makes these great artists play the way they do.

About 20 years ago I started learning mandolin, and began to concentrate on acoustic and resonator (slide) guitar. This was something of a new beginning, and I discovered a whole world of folk, bluegrass, and country songwriting which I had sadly ignored before.

“The impact of Hank Marvin’s Fiesta Red Stratocaster, possibly the first one seen in Britain, was a shock.”

How did you first get in touch with guitar? What in particular fascinated you to begin playing this instrument?

In 1959 Cliff Richard and The Shadows began to appear on BBC television. The impact of Hank Marvin’s Fiesta Red Stratocaster, possibly the first one seen in Britain, was a shock. It wasn’t even immediately clear what sort of instrument this was. The sound it made was pretty thrilling too. I was hooked (along with thousands of others, I assume). This was the start of a guitar fetish that I still haven’t quite thrown off.

Hank and his Strat was the first sensation; then came T-Bone Walker, Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, and The Beatles, playing and singing their own songs; then Clapton and Townshend and Peter Green; then Hendrix; and so on. The 60s was a long series of musical revelations, boundaries expanded and crossed, risks taken. I consider myself very lucky to have been growing up during this explosion of popular music. It was a pretty cool time to be young.

How did you originally meet John Wetton and what was he like?

John and I met at school when he was 13, and I was 15. His exceptional musicianship was apparent right away, and the instrumental group I had started a year earlier persuaded him to join. We also began to sing because he made it look so easy. His innate musicality allowed him to play a piece on piano or guitar after hearing it just once; rehearsals were sometimes fraught because the rest of us had difficulties keeping up with him.

John and I were friends for 55 years. Together we progressed through the early 60s from rockabilly to The Beatles, then from rhythm and blues to soul; by this time, the band was called The Palmer James Group and we were working most weekends at venues all along the south coast.

There were no discos or DJs in those days, so if a pub or club wanted music, there would have to be some kind of live band present. Consequently there were lots of chances to play; I recently found diaries from 1964-65 and was astonished to see that I had noted more than 100 gigs in an 18-month period. We were all still at school.

In 1968 I returned to Bournemouth after three years at university in Wales, and with JW on bass and vocals, John Hutcheson on Hammond organ, and drummer Bob Jenkins, formed Tetrad, a first attempt at a professional band. Unfortunately, we didn’t trust our talents sufficiently to write our own material; basically we wanted to play the songs our heroes played, that is, by just about anyone on Island Records, plus Cream, The Nice, and later Vanilla Fudge. We drove endless miles, earned very little, and fantasised about going to live in London. At some point we made a demo recording at Decca Records, but nobody really needed another version of ‘White Room’ or ‘Time Of The Season’ and nothing came of it. After a year we decided to give up.

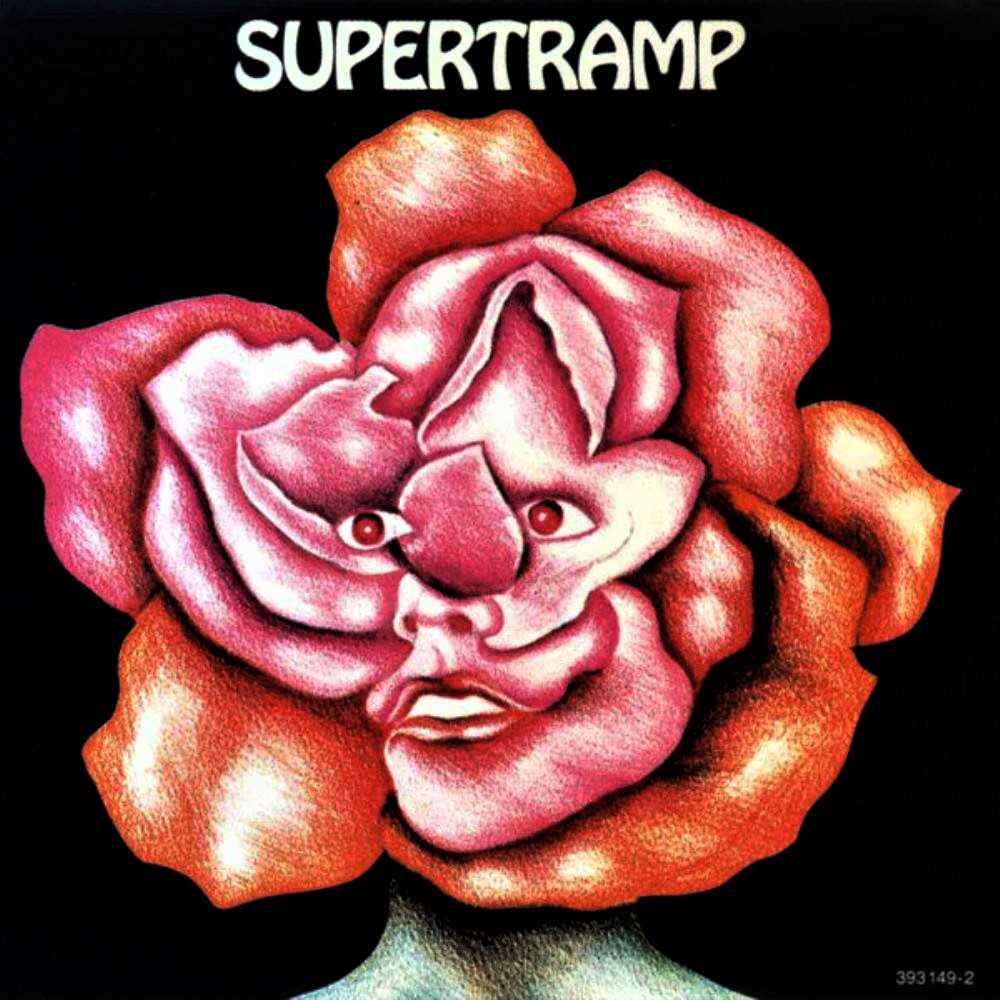

I believe one of your first more ‘serious’ involvement with music was when you formed Supertramp. Can you elaborate on the formation of Supertramp? What was the main concept behind Supertramp?

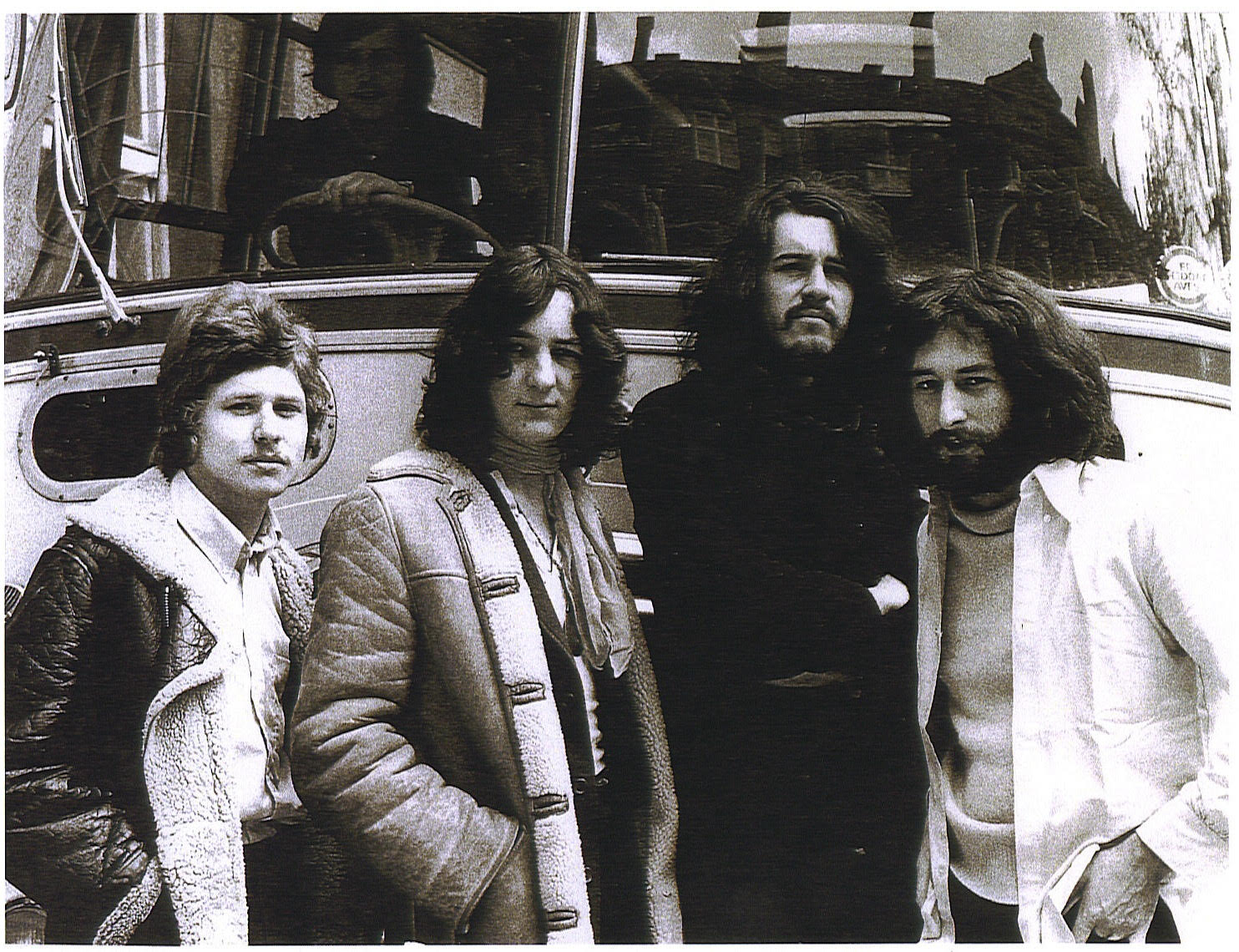

Supertramp was formed around Rick Davies, who had come into contact with a guy living in Geneva called Sam Miesegaes. Sam felt inspired by the Zeitgeist and wanted to break into music management, although he had no experience in the field. He was however wealthy enough to interest certain London music-business pros, who placed an advertisement in the ‘Musicians Wanted’ column of Melody Maker, to which I responded in August 1969.

Auditions took place in a tiny one-room rehearsal and demo studio which opened directly onto a side-street near Shepherds Bush Common. It looked like a padded cell. In 1969, London had a

population of about 8 million, and at least a quarter of these were guitarists; there was a long queue. Inside, air conditioning consisted of the occupants’ diligent in- and exhaling through the paper filters of dwarf cigarettes (Players No. 6) which were fashionable among Britain’s thrifty in this era. I arrived in the late afternoon, having auditioned somewhere in St Johns Wood earlier in the day for a band that was to become Wishbone Ash.

Rick Davies lurked behind his Wurlitzer, exhausted by the confrontation with this endless stream of young hopefuls – from which, however, he had already chosen Roger Hodgson. Roger was now helping with the auditioning process. I think I played and sang the Sonny Boy Williamson standard ‘Eyesight To The Blind’, followed by Donovan’s ‘Season Of The Witch’, a current ‘underground’ favourite which offered plenty of scope for jamming.

Rick had implied that as the guitarist’s job had gone to Roger, the only reason for my taking a shot would be to demonstrate my talents as a vocalist, which were not very impressive. So I was more than a little surprised when Rick called a couple of days later and asked me to join. The Wishbone Ash guys called too. I must have had a good day.

At first, the main attraction was the offer of a weekly retainer – six pounds, I believe – which was a most unusual enticement for a fledgling band at the time (and probably still is).

By the end of August 1969 we were all living at Botolph’s Bridge House – I remember it fondly – in Romney Marsh, Kent, an extensive and slightly mysterious stretch of land which was still under the sea when the Romans came to Britain. The house stands among fields at a windswept crossroads, isolated except for a pub on the corner opposite. It has a beautiful garden. It was a good time. I think we all enjoyed getting to know each other; I hope Rick and Roger remember it that way too. When we weren’t putting new songs together or trying out standards for inclusion in our repertoire, we could go for walks along the sea front or play darts at the pub. One day we invited a hedgehog into the living room, and as a result everybody had fleas for a week. Roger used to take a guitar along to the remains of a Roman harbour left high and dry on the hillside about 1 km behind the house, and sit there in the sunset, trying out songs . . .

In October (?) we made a first attempt at recording a single – ‘Remember’ (which became ‘Words Unspoken’) and the (rightly) forgotten ‘Saying No’ – at Trident Studios, Soho, London, produced by Gary Wright (‘Dream Weaver’). We were appalled because Gary spent the best part of half of our precious recording time (2 days) tuning the drum kit. At the time he was playing with Spooky Tooth, a band we all admired greatly (and for whom the term ‘heavy rock’ was invented, incidentally.)

What sort of venues did Supertramp play early on? Where were they located? How did you decide to use the name ‘Supertramp’?

Our baptism of fire was a 5-week residency in the PN Club on Munich’s Leopoldstrasse. Starting in November 1969, we played 5 half-hour sets every night (7 sets at weekends) except Mondays, when German rock and progressive bands took the stage. Here we developed songs for the first album, like ‘Maybe I’m A Beggar’, ‘It’s A Long Road’, ‘Nothing To Show’, and ‘Try Again’ (this last being the climax of our show all through 1970). We also played ‘Season Of The Witch’; Oscar Brown Jr’s ‘Sing Hallelujah’; Horace Silver’s ‘The Gringo’; an extraordinary instrumental called ‘Turnstile’ written by a classical composer and eccentric, David Llewellyn, who lived in Munich at that time; a bunch of Chuck Berry songs and r&b favourites . . . it was a pretty mixed bag, and an ideal situation for getting a rock group together. Sometimes our amps blew up because the electricity supply somehow depended on the performance of the club’s pinball machines. In between sets we drank watery Dinkelacker beer or climbed up out of the cellar to the freezing street for pizza-to-go at the legendary Picnic cafe a few metres further along. We slept in a four-room apartment owned by PN boss Peter Naumann on the opposite side of Leopoldstrasse.

Film-maker Haro Senft lived just round the corner from the PN, and often came to see us. His film ‘Fegefeuer’ was nearing completion, and he showed it to us on the cutting-table. He had an amount of 35mm material left over from the shoot, and on December 14th 1969, he used this in two cameras to film us doing our 10-minute version of Dylan’s ‘All Along The Watchtower’. I think it was our last night at the PN before leaving for a week playing a club in Geneva. Why didn’t we choose one of our own songs? I don’t know. It would have been a much better idea.

Before we recorded the first album, we were agonising over what to call the band, and I remember having the impression that all the best names had been used up . . . but then W. H. Davies’ book ‘Autobiography of a Supertramp’ came to mind – I had read it some years before. The choice of the name had nothing to do with the book’s content, however, which I had largely forgotten.

We returned to Munich in spring 1970 to write and record the ‘Fegefeuer’ soundtrack. Roger and I sat at the cutting table in Haro’s apartment for hours, looking for and timing sequences which seemed to call for music. Then we set up our gear in a ballet studio – it was a wooden shack in a nondescript Schwabing back-street; to reach it we had to cross a muddy yard full of monstrous and savage dogs – for a week or so and set about composing bits of music. Some ideas were new, some we had already tried out in England, and some dated from Rick’s workouts on Sam Miesegaes’ Bösendorfer grand the previous year. I wrote the guitar stuff, Rick wrote the organ stuff, and Roger did the weird noises and effects. He was a very good, McCartneyesque bassist.

The music was recorded in the caverno us Bavaria Studios, Munich, by house engineer Hans Endrulat. We synchronised the pieces to their respective film clips on the spot, Hollywood-style, playing in front of a full-size screen. Haro certainly made no compromises here.

Between 5th June and 15th December 1970 we played 70 gigs all over Britain. We had been signed on by the all-powerful Chrysalis agency, and were obliged to play any job they offered. The college circuit was important, but Chrysalis also sent us to the back rooms of pubs, strip clubs, and village halls. On the other hand, there were gigs at all the classic London venues, the Isle of Wight Festival, and the gigantic Grugahalle in Essen.

In the final weeks of the year our personal relationships were going bad, mostly because our very different personalities were bundled up together at close quarters all day, every day. The band received on average about £30 per engagement. Expenses swallowed everything. Sometimes we had to drive all night because we couldn’t afford a hotel; sometimes we could afford

a hotel but it was horrible; and often it didn’t look as if we were getting anywhere with our music. When I parted company with Supertramp, after a gruesome two-nighter at the Zoom Club in Frankfurt just before Christmas 1970, I had two pounds and ten shillings in my pocket.

Truth to tell, I just didn’t have the same degree of talent as Rick and Roger. Nor their tenacity: they soldiered on through another 3 years of broken-down vehicles, changing line-ups, miserly wages, and constant disappointments. Their international success is hard-earned and well-deserved.

What influenced the band’s sound?

That’s difficult to say. We had just come together, and all the personal influences did not really blend during the time I spent with the band. I think the first, eponymous, album was probably influenced by King Crimson’s ‘In the Court of the Crimson King’, which had just come out. (Of course I had no idea that I would be writing stuff for KC a couple of years later.)

In autumn 1969 we had tried out a Mellotron, but Rick didn’t like the lack of attack (the delays caused by the mechanism wheezily seeking the appropriate tape loop) and the infamous tuning problems.

Roger’s voice and songwriting style is unique, all his own. Rick Davies’ muscular keyboard playing is certainly informed by his love of big band jazz and his exceptional rhythmic sensibilities – he’s also an excellent drummer, one of the best I’ve been lucky enough to play with.

What’s the story behind your debut album? Where did you record it? What kind of equipment did you use? How many hours did you spend in the studio?

The album material was demo’d in a back room in Geneva using two Revox A77s. Sam Miesegaes did the rounds with these tapes, and A&M’s new London office took us on. Morgan Studios in north London, which had a certain mojo in that period as McCartney had just recorded his first solo album there, was booked for February-March 1970. I can’t remember how long we needed . . . must have been at least two weeks. Stupidly, we insisted on starting the sessions at midnight, believing that the vibes would be better. But being cool has a price, and everybody – particularly the remarkably patient and talented engineer Robin Black – was inclined to fall asleep after about 2 a.m. We produced ourselves, another mistake, because none of us was quite sure what a producer actually did.

“50 years on, I find it very gratifying that the first Supertramp album has found fans among people who were born years after it was recorded.”

We simply set up our stage gear (Hammond, Wurlitzer, 100-watt stacks for bass and guitar, drums) and banged out the backing tracks live. I’d say they were 80% pre-arranged. No click-track. Morgan had an 8-track system; we left it up to Robin to allocate and bounce tracks judiciously. Roger sang everything, admirably, in a couple of takes; we spent more time on solos, additional instruments, and percussion effects. Unfortunately there was no room for stereo drums, which would have improved the sound greatly.

50 years on, I find it very gratifying that the first Supertramp album has found fans among people who were born years after it was recorded. It bears witness to the eclecticism which rock bands could allow themselves in the late 60s and early 70s, the freedom to try out all sorts of stuff which later might have ‘alienated the target group’, as a latterday A&R person would put it.

It might be worth noting that the compositions were mostly genuine collaborations between Rick and Roger. I don’t think that happened very often afterwards.

You wrote the lyrics for the self-titled album. Would you share your insight on the albums’ tracks?

Well, Klemen, I usually like to let the gentle listeners find their own way into the songs.

In recent years I’ve often performed ‘It’s A Long Road’, because it rocks along nicely and offers opportunity for improvisation. Surprisingly to me, many have assumed it’s an old blues song.

I also do ’Shadow Song’ sometimes on solo outings, a nod to the past. It’s my favourite on the album.

“John Wetton was the intermediary between myself and King Crimson”

You also wrote lyrics for King Crimson’s albums: ‘Larks’ Tongues in Aspic’, ‘Starless and Bible Black’, and ‘Red’. How was to work with guys from King Crimson?

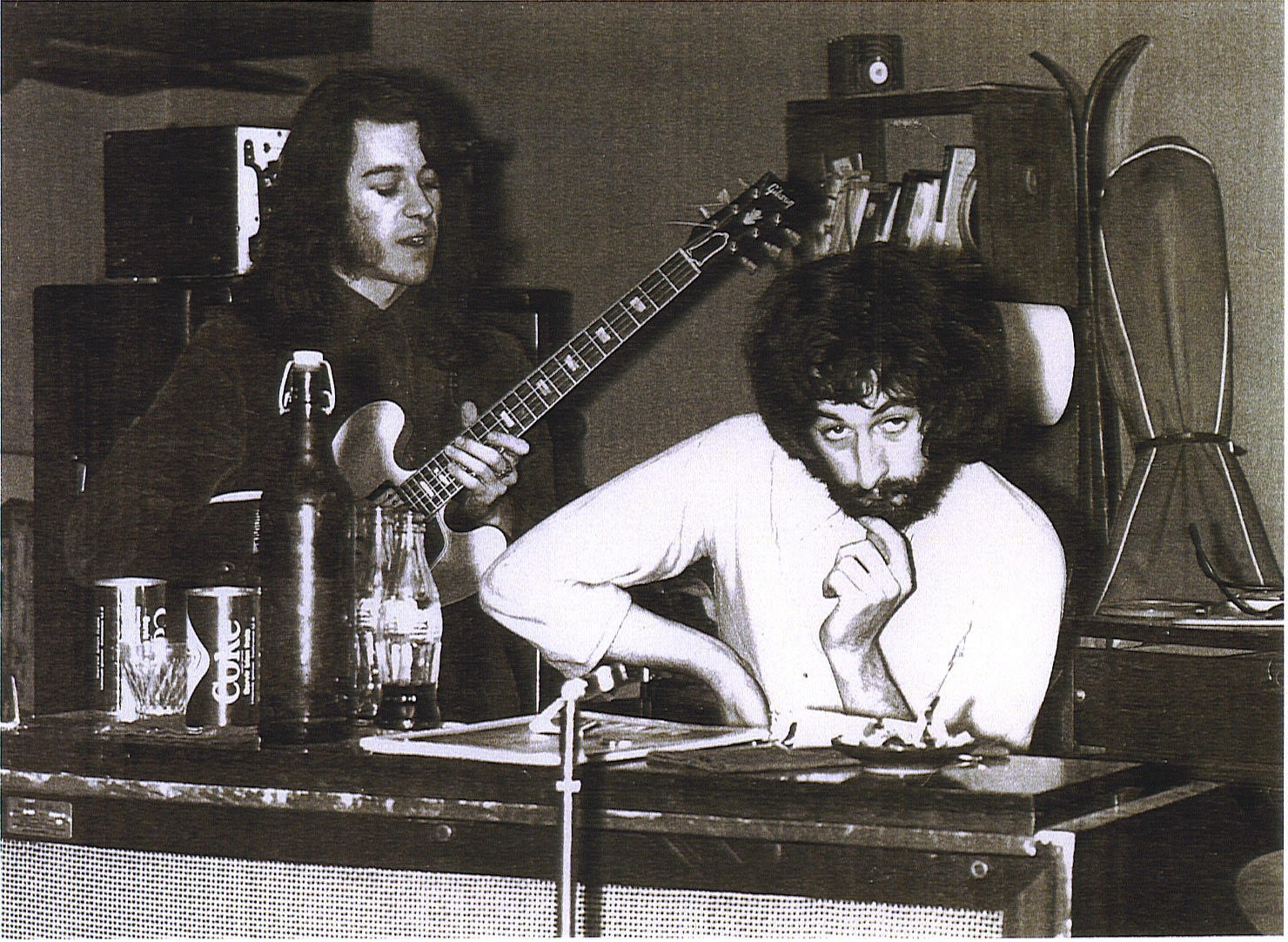

My predecessor as KC lyricist, Pete Sinfield, had of course been an integral part of the band, but my situation was quite the opposite. I had been living in Germany for a couple of years, and as I had found some work writing and recording music for films and TV, my connections to England were fading. John Wetton was the intermediary between myself and King Crimson. At no point was there a discussion of the lyrics with the entire band. I visited KC in the studios twice: once in Command Studios during the recording of ‘LTIA’ (1973), and later in Olympic during the work on ‘Red’ (1974), but these were courtesy calls. I joined them on tour in Germany for a couple of days – this version of the band was a pretty overpowering live experience – but the one or two long conversations I had with Robert Fripp did not concern the lyrics.

JW visited me often in Munich, and he brought KC demos with him, or I recorded his on-the-spot renderings on cassette: just the bare bones of the song, sketched out on piano or guitar. Sometimes I had no idea what the piece would finally sound like until the record came out. A couple of times John indicated how he thought the words might go – he was the one who had to sing them, after all. Otherwise, the guys simply let me get on with it.

How do you usually approach songwriting? Is your material set in stone by the time you record, or is it an ever-evolving process?

One of my nightmares is being obliged to spend months in a studio while songs are painstakingly glued together and multiple variations of everything are being weighed against each other. Some of my colleagues considered this to be the right way to do things in the 80s, and naturally there have been many great rock albums which have resulted from countless hours of re-recording and experimentation. But I don’t think the technical sophistication of a professionally-equipped studio is an essential requirement. The ideal for me is capturing a performance, not a hi-fi demonstration.

Thankfully most of the productions I worked on over the decades were recorded after extensive preparation outside of the studio had taken place, saving everybody’s time and money. Nowadays the material is put together in home studios anyway, and then perhaps mixed and/or mastered in a specialist environment; even in this case, I think it’s the performance that counts.

So yes, when I’m writing I like to have the song set in stone before I show it to anybody. This doesn’t rule out changes which necessarily happen when an ensemble piece is played solo, or vice versa. But the song should remain sacrosanct in all its possible forms.

You were also collaborating with a great group called Emergency.

Emergency was a six-piece jazz-rock outfit led by the late Czech multi-instrumentalist and arranger Hanus Berka, an energetic and likeable all-rounder. He was a brilliant musician who was really good at working under pressure (especially when he had caused the pressure himself), and I miss him.

I played guitar in Emergency for a year (1973), and wrote most of the lyrics for the album ‘Get Out To The Country’. We toured extensively in Germany – in fact, that’s how I got to know the place. I was basically the wrong guy for the job; I never succeeded in getting the required biting fusion sound, and was mostly occupied with covering up my technical shortcomings in the complex arrangements favoured by my jazz-orientated bandmates. Vocalist Peter Bischof, however, has remained a good friend to this day, and we’ve shared several subsequent musical adventures.

It’s absolutely impossible to cover your discography. Would it be possible for you to choose a few collaborations that still warm your heart?

After moving to Munich at the beginning of the 70s I just about scraped a living by writing and producing music for films – mostly PR shorts, experimental stuff, and documentaries. I’ve always

been interested in the mechanics of film-making; I even made an unsuccessful attempt to enrol at Munich’s prestigious film school (HFF). As the decade wore on, contacts in the German film world helped me get commissions for scoring TV plays and series, but gradually the lyric-writing activities took over, as I was being asked to supply words in English for every conceivable kind of composition.

As a British ex-pat, I had the advantage of being in demand as a native speaker; the bad news was that working on German, French, and Italian productions, the audience often didn’t understand much of what I wrote. By the end of the decade I was amazed to discover that the royalties from lyric-writing were paying the rent, and it was increasingly apparent that I was not destined to become a guitar hero (which had been the plan since about 1959).

Writing for commercial productions is a very different exercise from frolicing in the pastures of artistic freedom with early Supertramp, or King Crimson, or even Emergency; but it requires a

professional competence which I’m proud to have slowly learned. And occasionally I’ve enjoyed carte blanche: for example, in the 80s with albums by the mainstream rock group Munich (‘The Other Side Of Midnight’ and ‘You Never Know’) or, more recently, the David Cross Band (‘Closer Than Skin’ and ‘Sign Of The Crow’).

In the late 70s and early 80s I very much enjoyed working on pure dance/pop productions from Baby Records in Milan, particularly with songwriters Carmelo and Michelangelo La Bionda. Their disco tracks have a vigour which stems from the fact that the rhythm section was recorded live by studio cracks and not sequenced, as was soon to become the norm.

A collaboration that warms my heart is the ballad ‘In The End’, composed by JW and Jeff Downes for Icon; a beautiful melody with simple lyrics – although I needed a week’s work to write them.

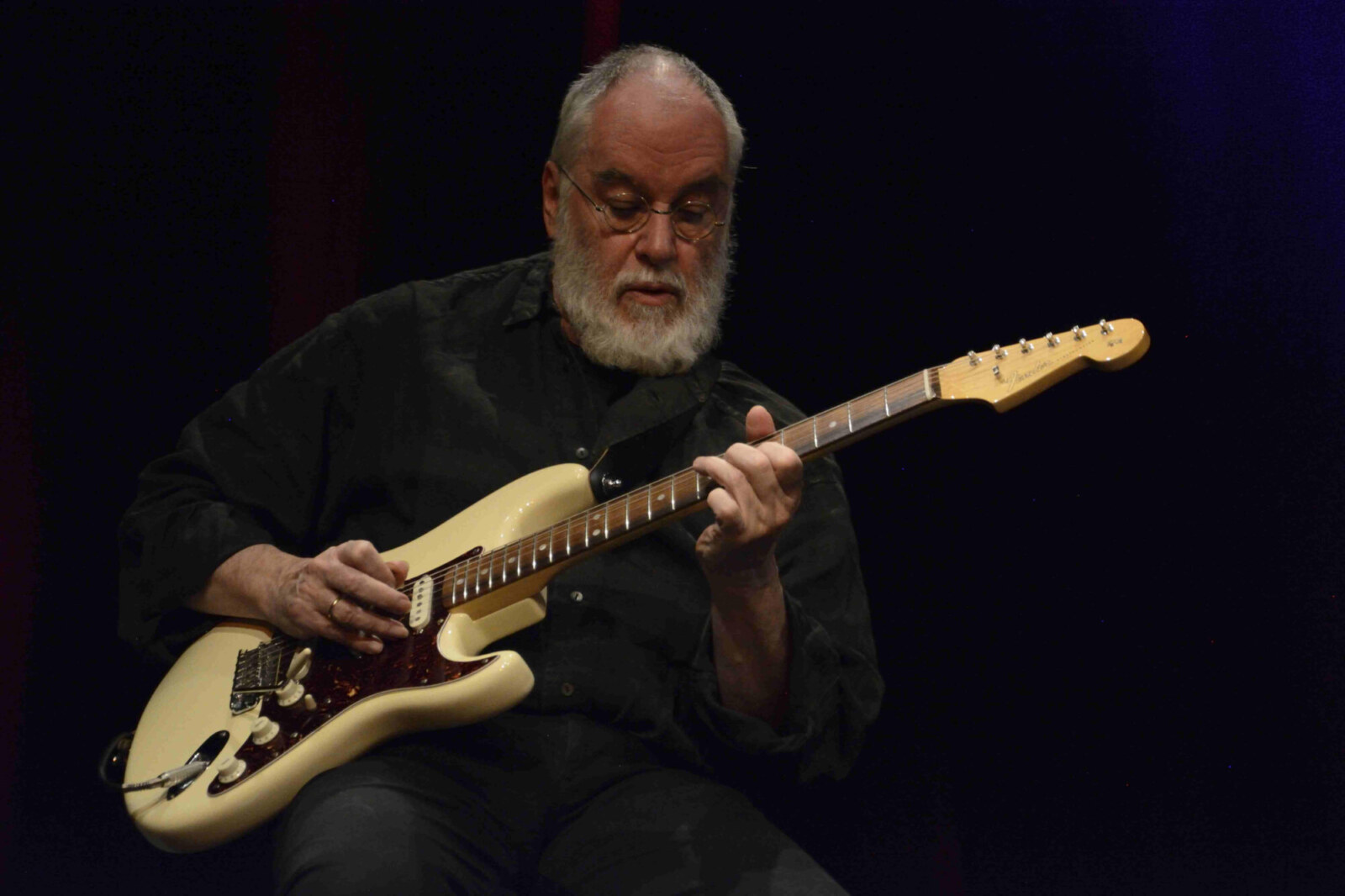

What can you tell me about your recent collaboration with Erich Schachtner? Two Heads is your project that has been active for several years now.

Erich is a classically-trained guitarist who can adapt to just about any style, including explosive rock stuff. In 2005 he strong-armed me to join him for a series of duo appearances playing pieces ‘From John Dowland to Django Reinhardt’ – completely unplugged on acoustic instruments. At first I was absolutely terrified before every gig, but thankfully we usually went down well (in culture clubs and cabaret venues), and although obliging me to rehearse more than at any time in my life, the Two Heads project has given me enough confidence to do solo singer/songwriter shows which I would never have dared to attempt 20 years ago.

Erich now lives 600km away in Berlin, so logistics are a bit of a problem, and in the face of a proliferation of guitar duos in recent years, Two Heads is currently on ice. We do still collaborate on various projects sometimes.

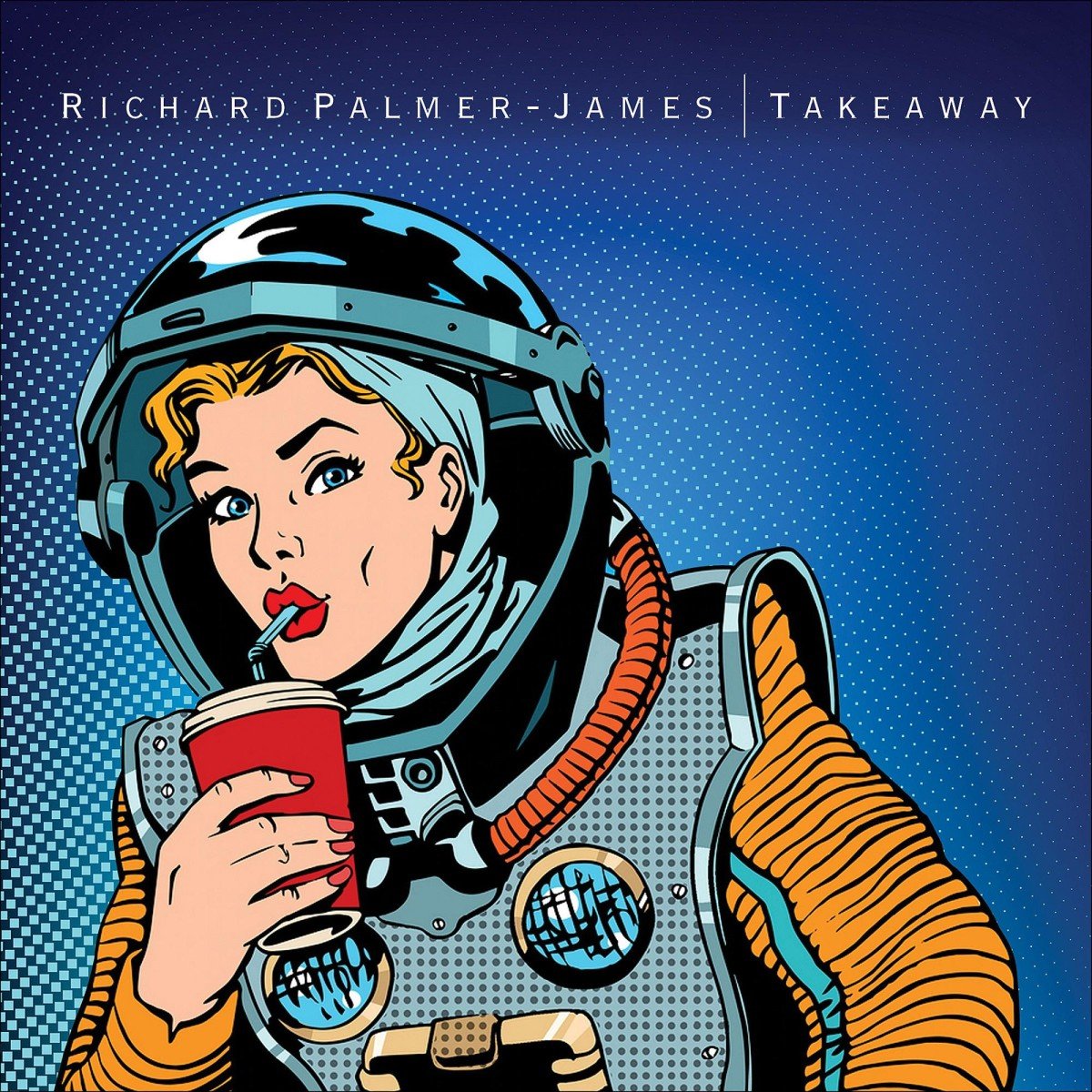

What currently occupies your life? Any other future projects we should expect?

In late 2016 I released ‘Takeaway’ (Primary Purpose 006), an album of songs I’ve written over the past two decades, partly for others, which I wanted to try performing myself. At the moment I’m working on a collection of all-new stuff, a bit more experimental, and perhaps more influenced by the ‘fuck you’ attitude which can help to make advancing age more tolerable.

Last year I did a couple of guest spots with other formations, including Alan Simon’s mammoth ‘Excalibur’ project; a few solo shows in Bavaria; and I was looking forward to more live activities this spring, but . . .

Let’s end this interview with some of your favourite albums. Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

Three 2019 albums I had to buy:

Sturgill Simpson, ‘Sound And Fury’

Sleaford Mods, ‘Eton Alive’

Cass McCombs, ‘Tip Of The Sphere’

I admire these class acts for doing exactly what they feel they have to. No compromise here.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

I’m 73. Five years ago, I at last worked out how to get a good guitar sound.

– Klemen Breznikar

I often remind myself that you were THE guitarist in Supertramp and have wondered how it would have ended up if you and Roger would have worked together up to and past “Crime Of The Century”. The influence of Traffic and especially Pink Floyd are to me, what set Supertramp apart from the 1000’s of other bands vieing for radio time, especially the addition of “Roger did the weird noises and effects” that were a part of Supertramps recordings, even after he had left the band (“Brother Where You Bound”). I’m probably in the minority of fans who don’t care if the original band (now refered to as the Mark III version) ever has a reunion because that time and age restrictions are gone. Supertramp is still one of my all-time fave bands, from first LP to last.

I joined the band in 1985 and was swept up in their English tradition and Rick’s musical vision. To this day I still consider Rick one of my greatest mentors and a continuing inspiration. For many years I’ve heard stories about those hard scrabble years of broken down vehicles and seedy hotels, but hearing Richard’s account really brings it home. Those guys really paid some dues and all the subsequent success (that I enjoyed with them) was well earned. Thanks for the heartfelt and informative interview Richard! (we met at the Royal Albert Hall in 1986, and a few times after that). Carl Verheyen

Rick

Congratulations on your great career. Long before you became famous I remember you playing at an event on an island off the coast of Istanbul you were great but my singing was not appreciated!