Siloah interview with Tiny Stricker

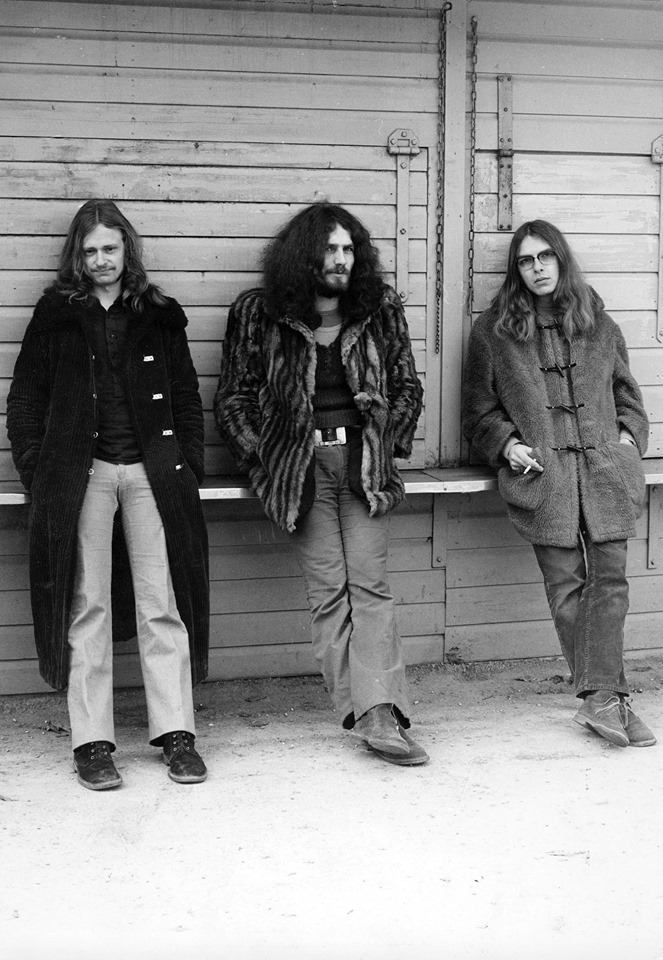

Siloah was a group of forward thinking people living a commune lifestyle and playing music. Heinrich “Tiny” Stricker is a famous German counterculture writer that was originally inspired by the beat poets. He wrote numerous of books and was member of this Munich group of people that was named after epic poem by John Milton. The band consisted of Thom Argauer, Wolfgang Görner, Manuela baroness von Perfall and Heinrich “Tiny” Stricker. The group didn’t consist of a fixed line-up but was a loose-knit crowd around a core group. Whoever was there and felt like it, simply played with them. Most of the time they were joined by Klaus Bartl and Guido “Pipo” Baumann. Special thanks to Walter of “Garden of Delights”.

You’re a very well known German writer. It’s a great pleasure to talk with you about your work. Who were your major influences at the start of your writing career?

I wouldn’t say that I’m a very well-known German writer, I think I’m still something like an underground writer, mostly associated with 1968 and the counterculture, but I have my fan groups and this is important to me. What inspired me and many others most at that time was probably the American Beat literature, writers like Jack Keouac, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. In fact, in early ’68 we staged a poetry event called “Beat&Lyrik” where three of us recited poems accompanied by a rock group, mainly bass and drums, a bit like Rap today. It all happened in a highly Catholic institution and I remember a row of nuns sitting in front of us looking rather bewildered when we shouted Slang expressions to intensify emotions. At the same time they didn’t seem to be completely uninterested.

On the German side, certainly Hermann Hesse was quite influential to us at that time. I took “Der Steppenwolf” with me when I went to Iran in ’68 as a kind of survival text. I also read books on Zen Buddhism, the cult book being “Zen in der Kunst des Bogenschießens” (“Zen in the Art of Archery”) by Eugen Herrigel. Somehow we imagined Japan to be at the end of our Eastern trip as a final destination.

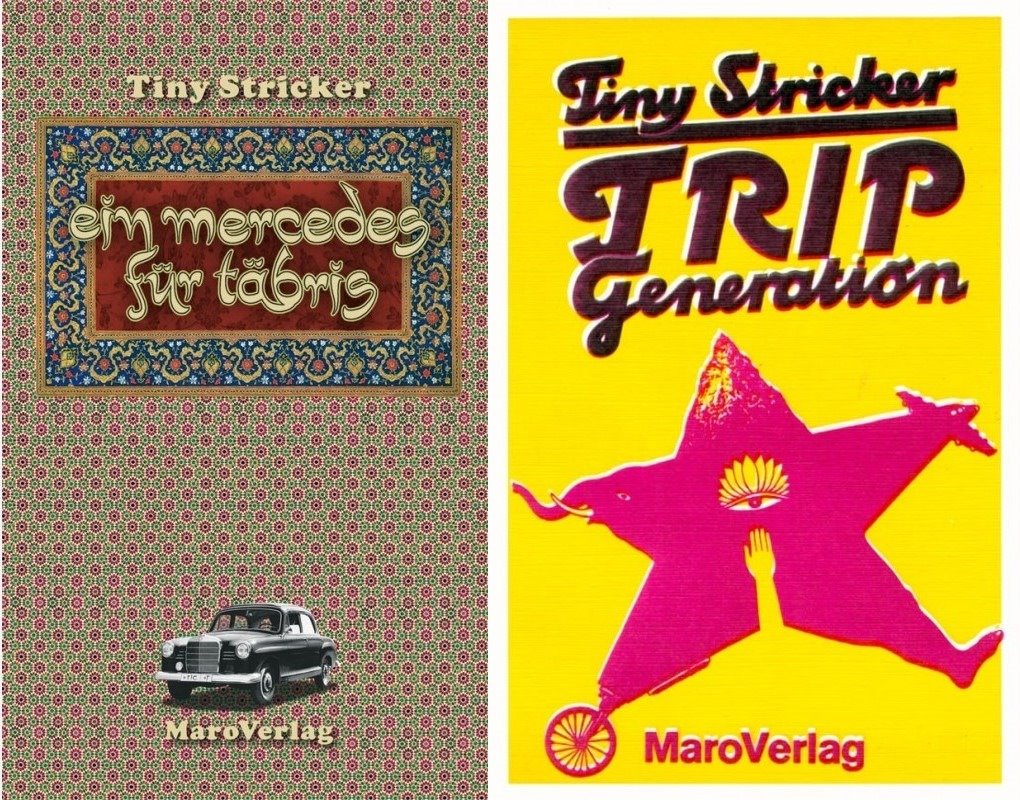

You did quite a lot of travelling in the late 1960s. You went to Iran and wrote a book “Ein Mercedes für Täbris”. It must been an exciting experience to go with an old Mercedes 190 D to the east for the very first time? What are some of your favorite memories from travelling to Iran?

I had to invent a big story about a carpet transport with a Munich carpet company for my parents to let me go. Another problem was that I couldn’t really drive this car. The trip itself then turned out to be quite rough. We traveled in a convoy, and the Iranian who was the real owner of the Mercedes was behind the steering-wheel most of the time, but he had no idea of traffic rules. He even made a U-turn on the Autobahn which almost killed us on the first day. Apart from that he was sexually unsatisfied and I had a pretty hard time. We reached Tabriz in two weeks losing half of the convoy, and then I had to stay at the Iranian’s home for several weeks waiting for my passport which had been sent to an advocate.

It was my first encounter with a purely nomadic culture, the house had no furniture, only a large carpet where we sat down for meals, and there were no plates or cutlery but instead we used scraps of flat bread. This was such a contrast to the post-war materialism that was so typical of my own environment in Germany. The house also had a beautiful oriental garden, and the Iranian had a lovely daughter who looked after this garden. Moreover, there was a tenant in the basement who spoke a bit of English and introduced me to old Persian literature, Hafiz, Nizami and Saadi, all this opened up a new world for me.

Your work “Trip Generation” reflects the time your spend in India. Are you always inspired by visiting different cultures?

I wrote a large part of “Trip Generation” in Chittagong, now Bangladesh, where I got stranded and eventually found a job in the “Seamen’s Welfare Club” in the harbor. I didn’t have much to do, just sit at a desk for hours and so I had enough time to scribble down notes on pieces of paper which I found in the office. At night myself and two other clerks slept on our desks with the fans on over us and I think I became much more easy-going in those days and acquired a much greater easiness and also confidence in life.

Later on through work I had to spend long periods abroad. It was sometimes very difficult, and for my wife who left her job in Germany even more so. But in the end we always found the different culture very rewarding, a kind of liberation or regeneration. In Greece and Bosnia-Herzegovina where we stayed, people for instance had a different sense of time, and this was a real relief from the hectic, “industrial” concept of time that we often have.

“Trip Generation is the expression of a counter spirit”

“Trip Generation” became highly influential for German counterculture public. How would you describe the alternative culture in Germany at the end of the 60s when a lot of people became more aware of the political climate around them?

1968 saw the youth rebellion in a number of countries, and certainly we had many things in common, the protest against the Vietnam war, new political ideals, our rejection of a merely materialistic capitalist system. To experience this new international spirit was fantastic. But of course, in every country the constellation was different. My parents, you see, had spent all their school days under the Nazi Regime, and they had a set of values according to that. I mean, they themselves were quite innocent, they were just victims of the system without really knowing it. But the confrontation with the parent generation in those days was quite hard. When I came home from Iran with long hair, a Parka, Greek sandals, rings and bracelets, the typical hippie outlook I was so fond of, and my mother met me at Munich main station, she said: “What do you look like, you are no longer my son.”

“Trip Generation” is the expression of a counter spirit: it’s about hitchhiking, travelling on the hippie trail, living with little money, broadening one’s consciousness, meeting many people, living a free life. Benno Käsmayr, a friend of mine and an “underground” publisher, managed to put the manuscript together, and to our surprise it was voted “alternative book of the year ” in 1970.

Your music group Siloah was born after you came from India.

When I came back from India, I stayed in Munich and ran into an old schoolmate who wanted to introduce me to a “real head”, as we said at that time, Thom Argauer. So we met him in early ’70 in a boarding school in Upper Bavaria where he definitely was the oldest pupil and the uncrowned king of the school living in a fancy room full of LPs, pictures etc. and constantly visited by girls. Thom and I became friends and together went on a trip in the summer trying to reach Essaouira, but couldn’t cross the Moroccan border because of our long hair. So we headed to Formentera instead, the island beside Ibiza. We joined a hippie community there often running away from the Guardia Civil which strengthened our relationship. On the whole trip and especially on Formentera we played music together dreaming of a new group in Munich.

Was Siloah a way to express experiences in other cultures on a different, non-literature level?

I think this is true. At that time we were fascinated by Indian music, by musicians like Ravi Shankar and the sound of sitar and tablas, but equally by a different oriental concept of music that was static, more like a meditation. I also brought some instruments back from my trip, flutes and a shenai, a kind of oboe used by snake charmers with which you could produce fantastic ecstatic melodies.

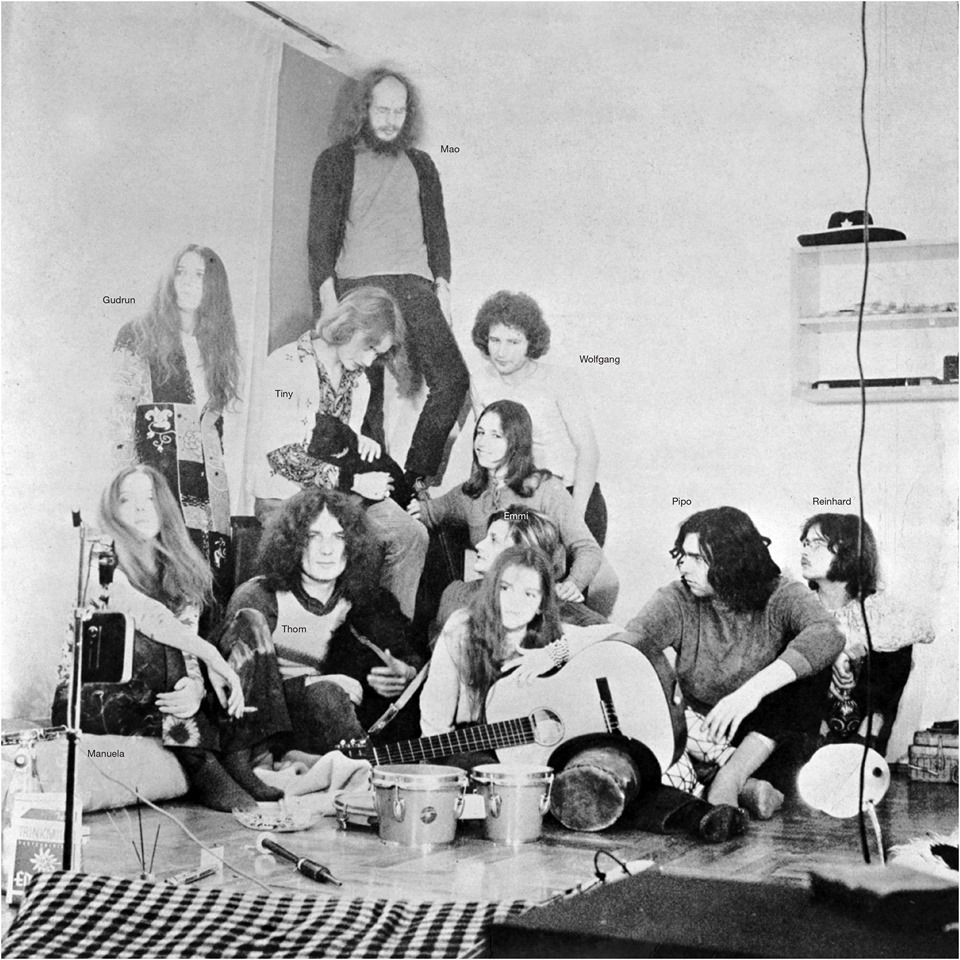

Can you elaborate the formation of Siloah? Who were members of Siloah that recorded the album in 1970?

On Formentera we had met Pipo who wanted to avoid consription in the Swiss army and he later turned up in Munich and became our drummer. Then in autumn 1970 Manuela, Thom’s girlfriend, joined us. She was actually a baroness from very old Bavarian aristocracy, but had run away from home and had no money at all. Manuela had a great talent for rhythm and played the congas. Thom and Manuela stayed in the Munich apartment of Wolfgang, the brother of another schoolmate. Wolfgang was an engineer and still went to work at seven o’clock every morning after playing and talking most of the night. He became our bass player and that was the core group.

“We installed a huge waterbed and when we sat on it and played it was like floating on a cloud.”

Did members live in a commune?

Thom had inherited an old, run down farmhouse on the outskirts of Munich from his grandmother and early in ’71 we set it up as well as we could and moved in. In many ways it was a fantasy place: in the main room we installed a huge waterbed and when we sat on it and played it was like floating on a cloud.

It was great to move together and thus establish much closer relationships. Gradually other people joined us, Klaus, for instance, who became our guitar player when Thom changed to keyboards, and his sister, and Brenda, an American girl who made clothes. Living in a commune without many personal belongings and in constant “togetherness” was a new and valuable experience for all of us, but it also had its shortcomings, and I can say a few words about that later.

How did you decide to use the name ‘Siloah’?

We made this LP and afterwards had no name for it nor a name for the group. After a while we all, especially Thom, got very desperate about the name. At that time I was still attending a seminar about “Paradise Lost” by John Milton at the English department of Munich University, mainly because I liked the title of the poem and thought it had something to do with our hippie philosophy. So I suggested “Siloah”, the name of a brook or pond in Jerusalem which appears on the first page of “Paradise Lost” as the name of the band. Thom immediately liked the melody of the name, the “pure unknown sound” as he said, because he had no idea what it meant. Others liked the slightly mysterious air about it, and so we finally kept it.

What’s the story behind your album? Where did you record it?

We recorded the LP right after Christmas 1970 in an old office block in Kempten which was about to be torn down. It was snowing outside and we had no heating, only a few radiators. The circumstances were harsh, and yet it was a memorable event, more like a clan gathering. People just kept coming and going, members of the Baumstraße commune where Thom and Pipo had stayed for a while, relatives of Thom, old school chums and so on. Some joined in, others just kept us company, and almost everybody contributed to it. Manuela brought a huge African drum which she had found in the attic of her father’s castle, Ali came along with a borrowed Fender Stratocaster guitar, Buddy, an old friend of Thom’s, unpacked his drum set, Gudrun from the Baumstraße brought a travelling flute player who looked like Mao and was called Mao etc. I think the LP, particularly the B-side, expresses this whole relaxed atmosphere of the meeting and the group spirit behind it, the music sounds more like an ancient tribal festival.

Where did you press the album and how many copies?

I don’t know where the first edition of the album was pressed, but I remember that we had 600 copies made. To our great surprise it was reviewed in “Sounds”, then the leading German music magazine. The review was not overwhelming, but it stood beside album reviews of Grateful Dead and other famous groups and all of a sudden we seemed to be well-known.

Walter from”Garden of Delights” actually rediscovered the LP in the 90s, improved the sound quality and made a CD out of it which led to a kind of revival of Siloah, which you can now also see in the Youtube contributions.

Would you share your insight on the album’s tracks?

Thom wrote all the songs on the A-side and the “leitmotif” for the B-side, which is mainly a prolonged improvisation. “Yellow puppets” is just a short and graceful intro, we imagined it to be like a gate to a magical garden and “Pink puppets” to be the exit gate when you leave that enchanted place. “Krishna’s golden dope shop” is a piece of static music, much like an Indian raga, and “Acid eagle” is similar. “Road to Laramy” was inspired by country music and became our most popular tune, even played on Bavarian Radio. The bonus tracks are interesting too: “Mit Tiny nach Tanger” is a recording of a very rough nocturnal jam session with members of Amon Düül and others on the banks of the Ammersee in ’70. And “Lady Jane – Lord X” was the music for a commercial for a hippie fashion store in Munich, which was shown in Munich cinemas.

How did you do the cover artwork?

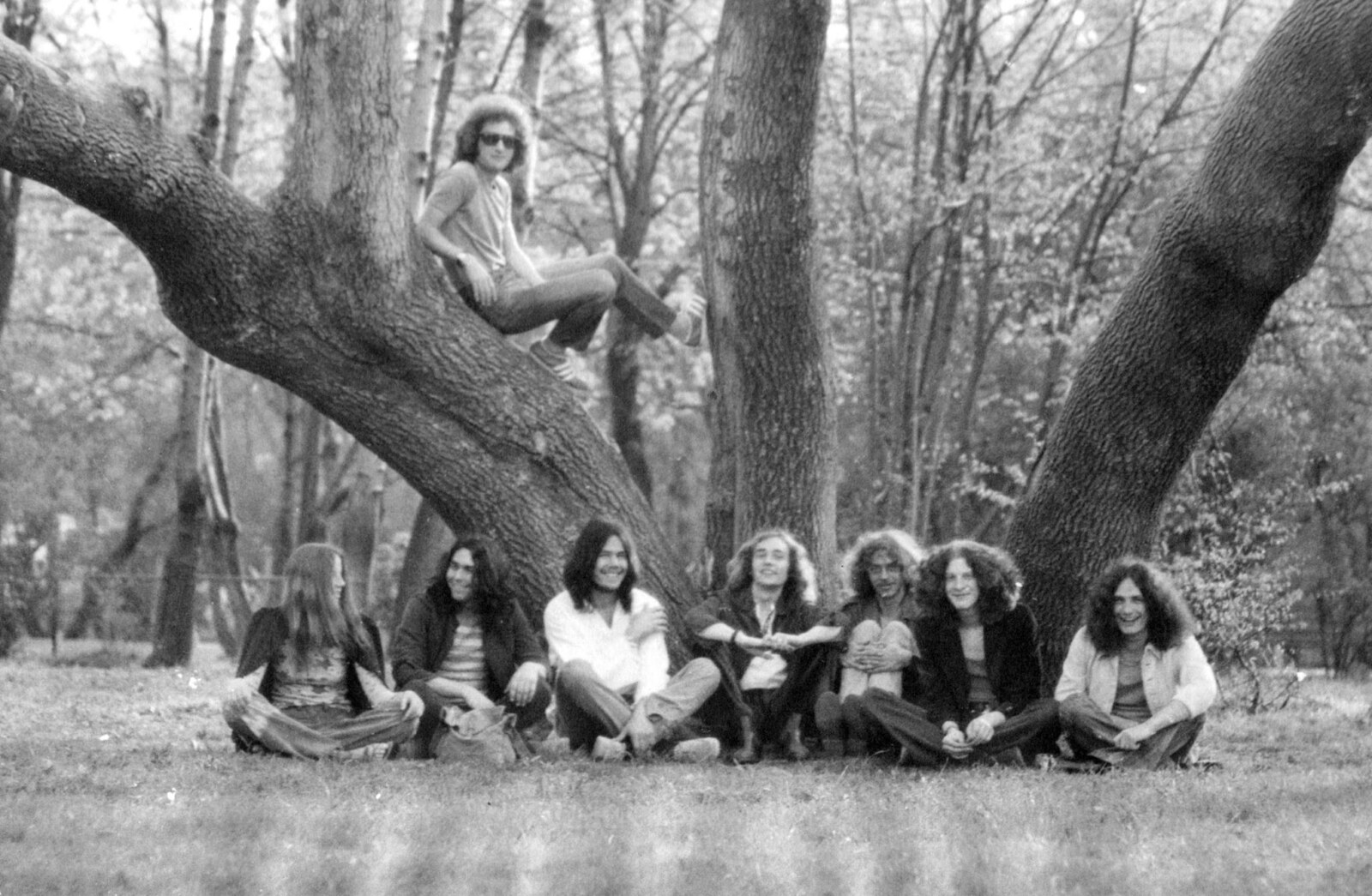

Kallert, a schoolfriend of Thom’s from Kempten, then a young photographer, took the photo of the group with some visitors right after the recording in that old office block where we stayed. We did not want to look like a normal group or “family”, more like an anti-group. So we chose the negative of the photo for the cover, which was Thom’s idea. It also reminded us of a moonlit, dreamy night.

Did you play any shows after the album was released?

We first played in a country guesthouse on the Ammersee where we were surrounded by cows and chicken. Then we played in the “Münze” in Munich which was an underground club. In early summer ’71 we appeared at two festivals, one in the Fichtelgebirge in Northern Bavaria and one on a castle in the Black Forest. Soon afterwards we started to travel and the group split.

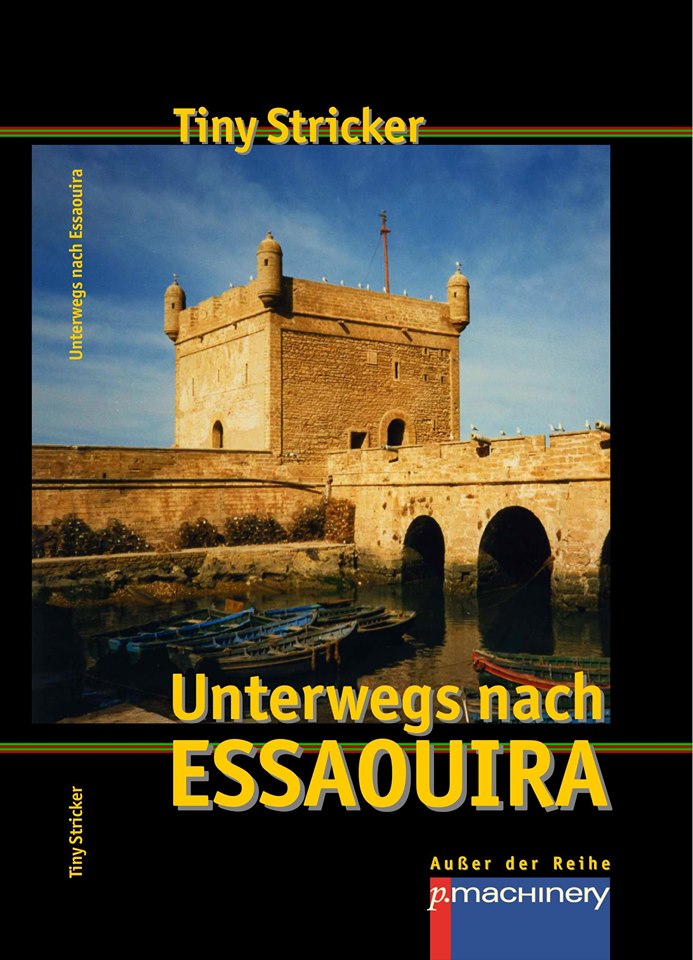

There’s a whole book about your experience with the band (“Unterwegs nach Essaouira”).

Yes, “Unterwegs nach Essaouira” is about my trip to Morocco with Thom, our stay on Formentera, the hippie island, and then our days with Siloah. Because I thought it couldn’t be 100 percent realistic anyway – as your memory always plays tricks on you after so many years -, I decided to write about it in the form of a novel. But it’s based on real events and so you could call it semi-fictional.

The book has two plots which are meant to be reflections of each other. One plot is set in Essaouira where I later stayed for a longer time and the other in Munich. Originally I wanted the Essaouira part to be utopia and the Munich part to represent reality, but it often turned out to be the opposite: Essouira showed the reality and Munich the utopia.

You were probably well connected with other people and bands interested in counterculture. Was there any particular German band that you enjoyed and find interesting?

We had loose connections with Amon Düül who at that time were a real cult band in Munich. As a matter of fact, Ulrich Leopold and Wolfgang Krischke from Amon Düül I were schoolmates from my old Gymnasium in Lauingen, and Thom had played in a school jazz group together with Chris Karrer from Amon Düül II. I liked the albums of both formations, especially “Paradieswärts”, the last album by Amon Düül I which was released in 1970 just before the Siloah LP. And only recently I saw Rüdiger Nüchtern’s film “Amon Düül Plays Phallus Dei” and I still found it magnificent.

Our favourite German band in 70/71 was probably “Can” with the bizarre Japanese singer who they found and immediately engaged on Leopoldstraße in Munich, as the story goes. But we also liked smaller groups like Popol Vuh, the whole “Krautrock” scene.

Is there any unreleased material? Siloah recorded another album (“Sukram Gurk”), but if I’m not wrong you weren’t part of it?

Unfortunately there is no such material – unless we find somebody who taped something from our sparse concerts. I mean it’s possible. Last year Wolfgang, our bass player, found some old Super 8 films again, and the material was put together so that you can now see a little film about our Black Forest concert on Youtube, an interesting document of that time.

“Sukram Gurk” was the title of the second Siloah album, but it was no longer the same formation. After the original group had dissolved in the summer of ’71, Thom founded a trio with him on the organ, Markus Krug on drums and Florian Laber on bass. For a long time I thought that “Sukram Gurk” was the name of an Indonesian dish because at hat time we frequented an Indonesian self-service restaurant. It is, however, Markus Krug spelt backwards, Florian Laber was actually found through an advertisement , which Thom had put in the newspaper, and he later played for “Sparifankal”, the Bavarian version of Captain Beefheart.

How would you summarize your time in Siloah?

The time with Siloah was great, but after a while living together in that rather secluded community in the old farmhouse and practising every day became too narrow for me and maybe the others, too. It was difficult to break out and I think gradually the commune or our version of it became a miniature version of a patriarchal society with a certain code of language and behavior. Also the big question hanging over us was whether we should become more commercial or stay “underground”. Thom wanted to go in the commercial direction and he probably was right, because we somehow had to earn a living, but myself and others wanted to remain an “anti-group”.

“Soul music gave me back my soul”

“Soultime” was another book that discusses the influence of american culture.

“Soultime” is a book about a high-school class in provincial Germany in ’67/’68, the changing social and cultural climate of that time, the liberation of individuals and the importance of American Soul music which fueled this liberation. Listening and dancing to the music of Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett and others, driving around, endless talking and going to discos were vital experiences for us in those days. We felt suppressed, didn’t want to continue with the lifestyle of our parents, rather find our own and Soul music helped us in that way. “Soul music gave me back my soul”, as it says in the book.

Have you ever started on a story and not finished it?

Oh, certainly, yes. I once started a book with talking animals and gave it up after a few pages which I sometimes regret. And for two years I wrote down impressions and observations on underground trains trying to write a sort of phenomenology of underground travel, but in the end I was not content with it and put it in a drawer. But it doesn’t mean anything. After some time you might rediscover an old, unfinished piece and perhaps suddenly like it or immediately see its flaws and improve on them.

What books are on your bedside table?

I found two volumes of Plautus’ comedies in a secondhand bookshop recently. The books were published in the 60’s in the German Democratic Republic, have a very sensible Socialist foreword and lots of annotations for any “questions of the reading worker”, as Brecht said. It’s easy to see why the East Germans liked Plautus, as in his plays the underdog, the slave, is the real hero. The comedies are indeed very funny and did a lot to revive my spirits after a heavy cold.

Which book or author do you always return to?

Walter Benjamin certainly is an all-time favourite of mine. I can re-read his essays, his descriptions of cities, his childhood memories of Berlin around 1900, everything. What I like about him? His thoughts, of course, his social and human insight, but perhaps most of all, his beautiful metaphors with which he can transform anything. As you probably know, he also wrote about his experiments with hashish in Marseille.

What currently occupies your life?

I am trying to write a kind of prequel to “Soultime”. This time it’s about the mid-sixties and the influence of pop groups of that time, groups like the Kinks and Troggs or the Beach Boys.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thank you very much, Klemen! I hope my answers didn’t get too long, but if they did it’s due to your great questions. What I personally found quite interesting, now looking back on this interview, is that there are so many similarities between then, I mean the period around ’68, and now. Youngsters today also more and more reject materialism, protest against neoliberalism and neocolonialism and fight for a better environment. I think this is a good sign.

– Klemen Breznikar

Nice interview, interesting man who seems to have lived quite the life. Good photos too. The Krautrock scene is one of the great and underrated genres and it’s good to know another group from that scene.