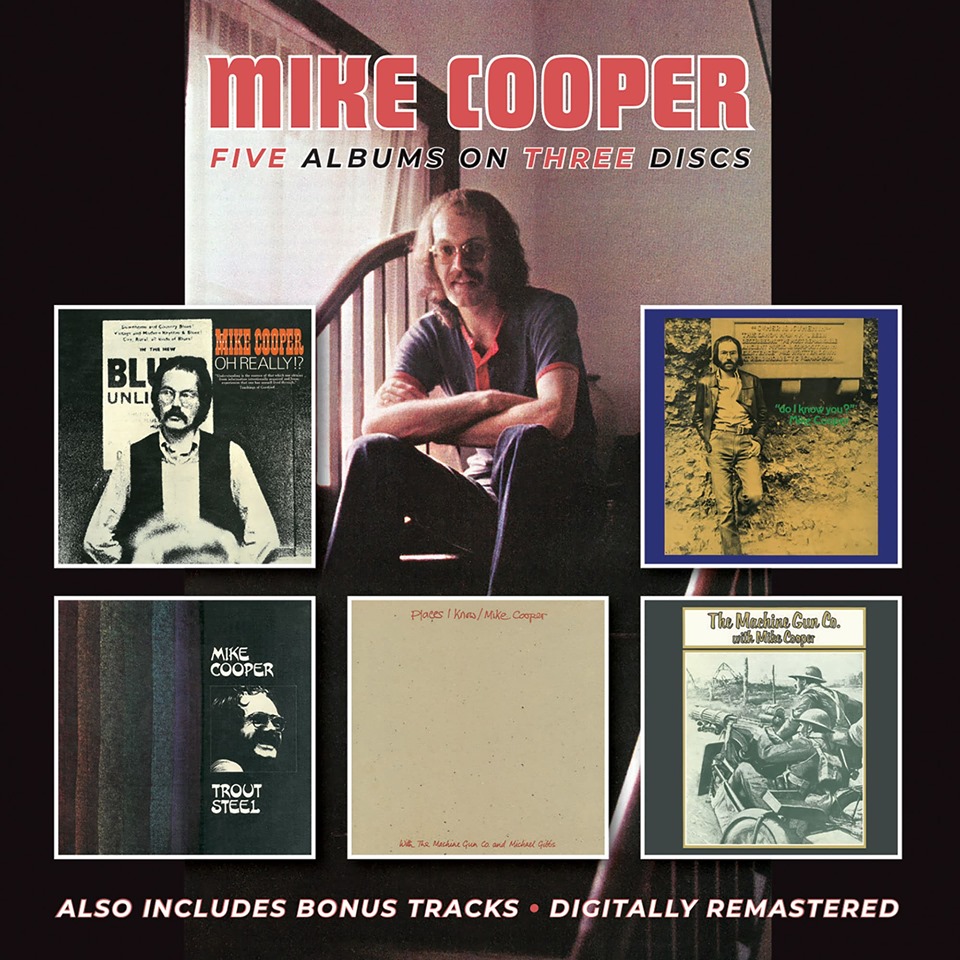

Mike Cooper: ‘Five Albums On Three Discs’

This important release showcases a musician influential in the blues boom of the 1960s who, by the 1970s, was adapting that form to other styles. From the next decade and still today, the self-taught Mike Cooper has been in the avant-garde of world fusion music allied to the electronic revolution while never ignoring formative roots. Not easy to categorise (like this untitled box-set!) because always applying his vision to a known or less known format, simply-put Cooper is an improvising outsider always in the swim. Quite a legacy, and quite a voyage!

Born in 1942 but briefly emigrating with his family to Australia in 1953, his teens were later spent in the fertile music area of Reading England. At 16, inspired by jazz in the days of pre-TV radio, he began playing guitar when with his drummer father they built their own one. An early notice was Slim Whitman’s ‘Rose Marie’, a UK #1 in 1954, which influenced some fresh-faced Beatles too. First performing in local skiffle groups, like many in the jazz and folk booms he rode the blues wave in the early 1960s after a concert by Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee at the Town Hall, then analyzing the works of such as Mississippi Fred McDowell and Blind Boy Fuller.

Adding harmonica to his repertoire (and a 1932 National resophonic metal guitar, like Taj Mahal and Son House, suitably percussive), in 1961 he co-founded The Blues Committee as singer only because the quartet already had two guitarists (Paul Manning and Dick Reeves). Noting that “melody has contours”, he created vocals his own way for a group that performed classic blues and R&B, as did their inspiration Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated. A live Marquee recording still exists, and in ’64 their repertoire expanded to include jazz and other modern styles. Co-releasing with guitarist Derek Hall a four-track EP of standards such as Terry & McGhee’s ‘Living With The Blues’ and a co-write with Paul Lucas, Out Of The Shades (1965) was named after an important Reading club for folk and touring bluesmen. Issued by the Kennet label of Newbury, it was financed by the club owner who also set up a weekly residency, Cooper having lost his job and marrying the same week! Appearing as a guitar-playing extra in the film That Kind Of Girl which didn’t pay the bills, he toured Holland including festivals with Jerry Kingett as well as Norway with Jo-Ann Kelly in 1967 while developing his own distinctive style.

That year he issued EPs with folk luminary Ian A. Anderson on Saydisc such as Up The Country (1968), and an LP The Inverted World (a side each and one track together) that was unreleased until 1970 when both had already signed to major labels. Anderson founded Village Thing Records in Bristol (Steve Tilston, Pigsty Hill Light Orchestra etc. featured on BBC radio) and is still well-known as the editor of Folk Roots. Adding slide and lapsteel, Cooper is also on a compilation Blues Like Showers Of Rain (Matchbox 1968) with Anderson, Dave and Jo-Ann Kelly, met like other friends in the forefront (John Martyn, Michael Chapman, Ralph McTell, Roy Harper, Stefan Grossman) gigging at prestigious London clubs such as Les Cousins, Half Moon and Bunjies. He appeared on BBC broadcasts by Mike Raven and John Peel (a debut in August ’68 from the first LP here resulting in 8 sessions until ’75, all repeated) as well as Holland’s Radio Veronica.

Peter Eden, who first recorded Donovan and Mick Softley, phoned to offer a Pye contract in 1968. Producer Eden took him to Pye Studios in Marble Arch on 30th December for just over a week resulting in Oh Really!?, augmented on two songs by Derek Hall, for the first of the five Pye/Dawn LPs on this lavish box with informative (though date-weak) booklet. Opening with one of the most emotive blues classics ever, Son House’s ‘Death Letter’, the eerie bottle-neck chimes and reverberating vocal by one clearly enjoying himself, could be the ‘40s: if covers can be authentic, this heart-felt rendition is it. It’s as if more than one song is encapsulated in each track though only one breaks three minutes thirty.

The finger-picking Delta-style delight with shimmering almost Gospel vocal of ‘Bad Luck Blues’ is part-based on Blind Boy Fuller (both are seminal influences, Cooper learning every note Fuller recorded), reuniting with Derek Hall for ‘Leadhearted Blues’ and Bessie Smith’s regretless ‘(Send Me To The) Electric Chair’. ‘Maggie Campbell’ (with middle space for Lightnin’ Hopkins’ ‘CC Rider’) revisits one of the genre’s oldest topics as does the Robert Johnson-like ‘Poor Little Annie’ with frenzied slide and ‘Crow Jane’. ‘Tadpole Blues’ is fine stomping: if had foot percussion it could be Joe Hill Louis reincarnated. Three instrumentals (‘Four Ways’; ‘Pepper Rag’; and the haunting ‘Divinity Blues’ as if by one left on the riverbank after everyone had gone home) round off this guitar masterclass.

Seen as one of the UK scene’s best acoustic blues LPs—the melodiousness with bite recalls the 12-string stories of Lead Belly, the intense but controlled vocal of Son House allied to Fred McDowell’s driving single chord or bottleneck style—the cover shot shows him at the 1st National Blues Convention where he also played in the month before recording. Son House, incidentally, didn’t tour the UK as headliner until 1970 (plus a BBC session) but by then Cooper saw new horizons. As did Pye, who formed Dawn Records for a more progressive roster perfectly suited to Cooper’s vision of favourite genres at a time when acoustic blues was becoming less commented-upon and mostly put on in folk clubs on set nights rather than in their own venues, or moved to smaller rooms in the developing college scene. (He has questioned the notion of a blues boom, believing it was just more noticed in the preceding years.)

Buying a big Gibson SJN Jumbo from Mike Chapman—whose ‘Rainmaker’ has often been compared to Cooper’s second album—the 27-year-old moved to the more intimate Sound Performance Studio in Denmark Street in London’s Soho. Alongside jazz influences rather than instruments, the songwriter augmented tracks with ambient field recordings (birdsong, church bells, the sea) as an artistic statement. Issued on Dawn in March 1970 (not ’69 as the booklet says; Janus in Canada/USA, Polydor in Japan), Do I Know You? features eleven songs in a gate-fold photographed at Reading Abbey, where a plaque claims the oldest piece of English music was written down in circa 1240. He is seen talking to G.T. Moore, another Reading and Dawn musician who was later in Heron and pub-rockers G.T. Moore & The Reggae Guitars (Cooper later appeared briefly in his The Outsiders in the 1980s).

Recorded in a couple of days with a streaming cold affecting his vocals and Eden again at the desk, openers ‘The Link’ and Martyn-like ‘Journey To The East’ are modal open tunings with drone effects creating breezy, driving fluency. More (but barely) folk-based, like ‘Thinks She Knows Me Now’ with lilting double-tracked vocal and female harmony, they create variant atmospheres when on the same CD as the debut here, though percussive, scintillating glissando and bell-like slide still permeate. The driving lament ‘First Song’ and ‘Wish She Was With Me’ is in keeping with the melancholic ‘Too Late Now’, a theme more poignant today. The title track delivers a weighty fugue, a bit like another pure English troubadour-traveller Mick Softley, as is ‘Start Of A Journey’ about just being yourself. The first CD closes with the philosophical ‘Looking Back’, a banjo-like folk song with soul-feeling, double bass suiting its tone by the South African jazz-man Harry Miller who’d worked with Manfred Mann, Mike Westbrook and Keith Tippet’s Centipede. Its style clearly prefigures his next albums.

Ney-sayers criticize his thinnish voice but the style is distinctly expressive in an ethos of less can be more; indeed, after a decade perfecting guitar he concentrated consciously on vocals to not sound as a copyist as do many white blues musicians. His approach was always technical indeed intellectual by design, he told an interviewer, whereas the old bluesmen were more emotion-focused when forging their own styles. Adapting what he heard at festivals and all-nighters (from Chapman, Martyn and Roy Harper to Americans like Stefan Grossman, Jackson C. Frank and Dave Van Ronk) for his own style of country (rural) blues, it is quite English in viewpoint: countryside blues perhaps?!

Sales were good enough to encourage Pye to up the budget for the next LP, such as more sessioneers, while a sojourn in Spain fuelled songs for his next LPs and two maxi-singles. Trout Steel (1970) features Stefan Grossman (while on his way to Rome), Nick Pickett on violin (John Dummer Blues Band and the solo classic Silversleeves), Mike Osborne (alto sax, clarinet), Geoff Hawkins (flute), John Taylor (piano), Alan Jackson (drums) among others in Mike Westbrook’s band. The upbeat, sax-bled love song ‘That’s How’ sets the scene for a new wider palette. ‘Sitting Here Watching’ and the eleven-minute epic ‘I’ve Got Mine’ show superb remastering of strident confidence with a Tom Waits-like band going for it. ‘Pharaoh’s March’, a seven-minute homage to Pharaoh Sanders, doesn’t jar with country stories (‘Trout Steel’; ‘Goodtimes’), the amusing advice of ‘Don’t Talk Too Fast’, or instrumental dedicated to the tragic American writer Richard Brautigan, who did a spoken voice for Harvest at the time that was first in Apple’s catalogue. ‘Hope you See’ is a honky tonk piano/violin hoedown with a twist-ending, a softer interlude for ‘In The Mourning’ (“Didn’t ask any questions / I didn’t want no lies / I could tell there was something / By the look in your eyes”). Poignant closer ‘Weeping Rose’ embellishes the guitar mid-trope of ‘March’ about a vanquished lover (“Go ahead, I’ll meet you further down the road”). A BBC live in concert in May, between these LPS, confirmed his standing.

One or two critics saw Trout Steel as country blues adapted to a melodic accompaniment, it certainly has the biggest nod to American styles: they see it as his best album, which depends on what you’re reacting to and looking for. Some call it a travelogue or soundtrack without a film, maybe, perhaps stream of consciousness with his own lyric content melded to structured jamming? What’s never disputed is that all his work is an exhilarating adventure each time.

Places I Know (1971) was planned as a double of different styles per side but, due to “the men in suits with cigars and bad taste in ties”, was issued as a single album followed by the ‘other half’ as The Machine Gun Co. With Mike Cooper eighteen months later, though both were recorded during two all-night sessions in June ’71. With some arrangements by Mike Gibbs, full-band backing (more than two dozen in all) and vocals by the Dawn Chorus (Norma Winstone, Jean Oddie Gerald T. Moore), Places I Know received notable air-play for some of his best-known songs. The same year Dawn issued a maxi-single with a track from the last two LPs plus the non-album ‘Ballad Of Fulton Allen’, alas not included, but two other picture-sleeve singles are: ‘Your Lovely Ways (Part 1 & 2) with Chris Spedding on 12-string guitar in 1970, ‘Time In Hand’ / Schaabisch Hall (1972). The upbeat first, with Roger Chapman-like vocals and violin, fades to show the A and (instrumental) B side break; the country-tinged folk-rock of ‘Time In Hand’ is backed with a dreamy, past-time instrumental of piano, cello and violin.

The LP highlights breadth of styles while tightly focused: from the countryish (‘Country Water’ and title track’s lyrics, unusually the shortest song) to the sax-blast stomp of ‘Night Journey’, the joyous love celebration ‘Now I Know’ with fizzing fuzz solo, and emotional ‘Paper And Smoke’ with echoes of Dylan’s ‘It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry’, while ‘Goodbye Blues Goodbye’ is tongue-in-cheek jazz (as when the poet John Betjeman was set to music; tuba, French horn etc.) as a reflection on Randy Newman’s lyric style. In fact the whole album was an exercise in making songs in the styles of various writers. ‘Broken Bridges’, a piano-led strong beat for what is nostalgic with the haunting refrain “All these things are mine and much more” leads to the punchy band-beat of ‘Three-Forty Eight (Blues For Or Against Andalusia)’, which should have been issued to world-acclaim as a hit (I at least remember it fifty years later): timeless still with shiver-effect like the truly beautiful ‘Time To Time,’ classical piano and strummed guitar floated by ethereal female harmonies (“It’s only when she’s gone / She comes to me in a song”). You may like the famous only (I don’t) but this magnum opus smokes the essence of that fecund decade’s first half and deserves much wider notice.

Disc three’s The Machine Gun Co… (1972) reflects more discoveries in longer songs (five, written in Spain) though backing is shorn to four top-notch musicians: Geoff Hawkins on brass from The Blues Committee and Cooper’s previous two albums, pianist Alan Cook (ex-Trader Horne), Les Calvert (bass) who worked with touring Americans and Mungo Jerry later, and Tim Richardson (percussion). With Eden in the same cozy studio enhancing the vibe, these local musicians worked with Cooper before (though had split before the delayed release), rehearsing these songs during the early summer of ’71. Opener ‘Song For Abigail’ is an extended style-feast that’s been called “avant-country-reggae” i.e. country-like lapsteel and lyrics building to a piano-pinned, percussive guitar romp with shades of Tim Buckley’s Lorca. Pastoral lyrics adorn folk-rock ‘The Singing Tree’ splattered with delicate free saxophone, the fast pace continued in ‘Midnight Words’ about going home. Pedal work phrases the atmospherically joyful fifteen-minute ‘So Glad (That I Found You)’, pointing to his next albums while “listening to the breeze searching for the song”. It’s rare for a love lament about its promises to close an album in such a beguiling way (‘Lady Anne’).

Rawer than usual, it highlights his origins from even before Pye with friends that knew his previous styles. Looser but paradoxically more structured with each knowing where the other could or might go, boundaries become more elastic and blurred; if jamming, it is so tight it could almost be a virtuoso octopus. Often seen as his magnum opus, the culmination of years of craftmanship to achieve originality among diverse traditions, this can be felt, but needs to be heard with Places I Know because the pair form a spell-binding achievement.

Seeing out the last two years of his Pye contract without recording, led to Life And Death In Paradise (1974) on the DJ Tony Hall’s Fresh Air imprint as “one of the most memorable [albums] to create” in a continuing career of experiment. They’d met in Spain when the host suggested his own album with Mike Osborne, South African and Reading musicians that was recorded practically live; it “closed a bracket” (with some very bitter lyrics) for the songwriter, marking not only a return to jazz roots with diverse musicians but also self-production for a short-lived label that had kindred spirits like Lyn Dobson. This year and the next saw his last Peel radio sessions, with no Dawn material. He told M-Magazine in 2015 that by then he’d “left behind the safe shores of melody and conventional harmony to head out into the sea of timbre”, exploring the globe for inspiration (and homes) as an “icon of post-everything music”, as a later label-owner put it. Mike Cooper’s subsequent work is so extraordinarily wide that we can only touch on it, briefly glimpsed by this reviewer when he saw him recently on the same Warsaw bill as Mike Chapman in a tiny Jewish bar-club that’s now a car-park.

A compilation (Grossman, Jo-Ann Kelly, Son House etc.), Country Blues Guitar Festival in 1977, was his last recording of the decade. ‘Ave They Started Yet? (1981, Matchless) was a live recording (over four hours!) involving dance theatre reflecting Cooper’s now-wider scope. Soundscapes via guitar/electronics resulted in sound installations, videograph documentaries, music for silent films etc. while working with such free spirits as Lol Coxhill, Dave Holland, David Toop, Ian Anderson again (re-interpreting Inverted World), G.T.Moore, Cyril Lefebvre and many others. Just as his “aural perspective” had once been influenced by a local Caribbean music club, and lapsteel resulted from an American stranger in a Reading café applying a glass from the table, he augmented his sound with guitar pedals as they came on the market. Self-taught, he modestly doesn’t see himself as a guitarist but as an aid to accompany expression. Microtonality is the essence, and just as Ornette Coleman’s harmelodic approach was an early but enduring influence, he found that the Hawaiian guitar style was in new Indian music and even Vietnam (the blind street musician Kim Sinh is mentioned). The “broken and elastic rhythms” that non-Europeans use were first collected on music cassettes he bought from a shop in Ealing Broadway.

Fascination with techniques led to a lasting exploration of Polynesian music (first visiting in 1994, he notes that its recordings predate the blues), Balkan, Iberian, Chinese and Arabic via strings and techno-sophistication’s loops and layers exploring ambience. Since the ‘90s it’s on Room40, Discrepant and his own Hipshot resulting in work as an artist-in-residence as far apart as Italy and Hawaii as a hands-on pioneer of world fusion music. Prolific in chosen styles, since Radio Paradise in 2011 he’s released White Shadows In The South Seas (2013), New Globe Notes (2014) with booklet by David Toop, Cantos de Lisboa (2014), Light On A Wall live in Beirut (2015), Fratello Mare (2015), Kiribati (2016), Reluctant Swimmer/Virtual Surfer (2017) etc. Raft hymns solo sea-travellers that year, a vinyl self-release Blues Guitar (vocals/guitar collaged together) was re-issued by Idea Records with graphics by Tom Rechion, who worked with the Beach Boys. Uncut (June 2019) reviewed three of these albums at 8/10 each and this BGO box-set as 9/10, which grew from the American label Paradise of Bachelors reissuing three of them and his first recording Out Of The Shades on vinyl to wide acclaim, achieving Best New Releases from Rolling Stone and Pitchfork in 2014.

Today the steel guitar is wired into a table of electronica (he’s cited the patterns of Silver Apples here as an influence) to create raga-like deconstructions of living multi-cultural music underpinned periodically by archeological blues (as in Mali and elsewhere). Lyrics are picked up or discarded on the floor around his performance in a riveting stream of consciousness shaping sound to fit mood in what’s been called a hypnotic travelogue. Richly evocative, full of ideas, he might intersperse a Van Dyke Parks’ cinematic-like song for good measure while finding his own eclectic place among the tendrils like a glow worm spinning silk webs. As a self-professed anti-art-snob, he’s glad he never went to art school “where they brainwash with established ideas and forms” teaching people to be curators and business managers not artists”. Even during the jazz/blues/folk booms his compass spans the world-dial seeking tones, moods, textures and atmospheres. Mike kindly took time out from his busy schedule to share some thoughts:

You played in skiffle groups at the outset of your career. Why do you think its heyday was short-lived and was it seen that way at the time?

It didn’t seem short-lived then I think because we were all much younger and time goes slower when you are young. Five years to a five-year old is its complete lifetime reference. Maybe the musicians gained sufficient confidence to move on to something else. Alexis Korner for instance went straight from skiffle to a jazz-based R&B band, which I loved. The record business and television probably wanted something less raw so they slowly homogenized it to the extent that it would eventually die out in its original form and the musicians move on, either into commercial success or related music and the blues boom was born maybe?

Do you retain the tapes of Blues Committee at the Marquee and did you consciously avoid releasing on Village Thing?

I think I have something from that session, there might be a track on my website. I was never asked to release anything on Village Thing and had my contract with Pye by the time that I recorded for Saydisc, which was the parent company. I recorded one side of The Inverted World with Ian A. Anderson and we may have put a false recording date on it to avoid any problem with Pye. The label was more folk based than I cared to be anyway. By the time I recorded Oh Really I was ready to move musically somewhere else anyway, having played the material on that record for at least seven years, and agreed to do it as a means of accessing the Pye studio with a view to doing different things. I had a very good relationship with John Peel and did many sessions for him as well as some ‘Jazz In Britain’ sessions with the Mike Gibbs Orchestra for instance.

Was it enjoyable working with Peter Eden? Donovan and Mick Softley for example weren’t so pleased in the preceding years.

My relationship with Peter Eden was, and still is in fact, always with mutual respect. I would never have had access to the musicians that I recorded with without him as my producer. He was well-connected, known and respected on the jazz scene, never less than supportive to my musical ideas and musical eccentricities all the way…I owe Peter Eden big time.

Most internet sites list you as the author of the debut’s songs excluding the Son House opener. Are they trad-arranged or self-writes?

‘Leadhearted Blues’ is my version of the Bertha Henderson singing with Blind Blake playing guitar record. I can’t say they are arrangements as such but more like mistakes arrived at by me trying to figure out what both of them were doing [but] getting it wrong in fact! That is true of almost all of that record and any other attempt of mine at playing blues.

Guessing you were disappointed by Pye’s splitting of ‘Place’ and ‘Machine Gun’, do you feel there was a lack of support by the label?

They let me record it, to be fair, but the lack of any other support was probably more of a problem eventually. We had no management or agent so work wasn’t forthcoming, we weren’t able to sell the records for them either. John Peel, bless him, was very supportive but we did very few gigs and in the end Pye didn’t want to do anything else with me. I was gigging solo but not enjoying it very much, doing the same material with just acoustic guitar, sometimes like the Hollywood Festival (UK) with a couple of other musicians (Geoff Hawkins on tenor sax and Les Calvert on electric bass). Richard Williams gave us a rave review, he was supportive as well. Pye just weren’t convinced that a double album would sell so they split it and held Machine Gun Company back in more ways than one.

Their decision partly contributed to the band split, and no US tour either. A maxi-single was issued of previous material for example.

Well as I said no one organized a tour for us, we were left to our own devices and eventually mutated into something completely different. I have tapes and there were Peel sessions of what it turned into: a bit of a rock band in fact and I started to lose focus to eventually walk away from it all for a few years. There are some interesting pieces in the archive there that haven’t been re-issued. ‘Goodtimes’ with Dudu Pakwana, Mike Osborne and Mongezi Faza is one of my favourites, ‘Too Late Now’ from the maxi-single with Mike Gibbs’ arrangement is very nice.

The timeless ‘Three-Forty Eight’, ‘Time to Time’, ‘Country Water’ would seem to be great choices as singles?

Thank you. There maybe you have hit part of the problem I had. That kind of decision would be taken up by a manager and I didn’t have one. I was a self-organizing, self-employed jobbing musician (as a lot of us were) still hacking round the folk clubs slowly losing touch, in my case, with the audience.

Did you ever meet or know the work of other quintessentially English folk individualists such as Mick Softley, Marc Brierley or Nick Pickett?

I have no memory of Mick Softley to be honest, Nick Pickett played violin on Trout Steel but didn’t know his solo album. I was very friendly with Mike Chapman and Ralph McTell, the Les Cousins crowd such as John Martyn, Roy Harper, Jo-Ann Kelly and her brother Dave. I played on a few Kicking Mule recording sessions for Stefan Grossman when I needed money, as we all do from time to time. I lost interest in the singer-songwriter/acoustic guitar thing quite early. In fact I never considered myself much of a guitarist, I still don’t. I was listening to pretty extreme free jazz by the time of Trout Steel and my guitar hero by then was Sonny Shamrock, I bought everything I could find with him on, including a lot of pretty bad Herbie Mann records who employed him. Sonny’s debut solo ‘Black Woman’ (1969) is an astonishing record and I got it when it came out; also Pharaoh Sanders’ ‘Tauhid’ of 1967 because Sonny was on it. This was in my head when I went and talked about my next record for Dawn with Peter Eden. That’s how I got all those wonderful musicians on it and what formed that music.

In the legendary clubs of that era was there a sense of camaraderie or rivalry?

Mike Chapman, Ralph and I sometimes did duo and trio tours together. Ralph’s brother became his manager but I think Mike like me never had one. I didn’t drive, and still don’t, but Mike loved to so that was quite convenient really. I spent many years travelling by train through the UK and Europe, even hated flying back then.

Would America have benefitted your career?

Probably but I would have needed someone to drive me. Actually, I have always had a love/hate relationship with the US. I’ve done short tours there (2000; 2002) and was actually flying to New York on the morning of September 11th 2001 but never got there, ending up in Amsterdam with about half a million others trying to find our baggage and spending the night in a reopened refugee camp before being shunted back to Rome. It then became impossible to go there as a musician without work visas and I really couldn’t be bothered with all that. Earlier, Stefan came to the UK for instance, so how much was there for us ‘white boys’? I know Jo-Ann Kelly went and had a horrible time, leaving mid-tour.

Have you considered revisiting your early work?

I wouldn’t want to do that really and probably can’t anyway, at least not the acoustic blues thing; my technique’s completely different now. I considered trying to do some Pye/Dawn songs with a band a couple of years ago but it would have been local with Roman musicians for a one-off. Maybe one day just for fun.

Would a multi-national label today benefit your exposure to world music?

I really have no desire to work with them because they work for themselves. I’ve had enough trouble with smaller labels that were reliant on multi-nationals in the past. Some of my post-Pye music is lingering in vaults unavailable to me or anyone else; getting paid is another problem with them so solved this for ten years by issuing 30 of my own CDs in various styles on my Hipshot label, from acoustic folk blues to avant improvised and a lot in between including silent film soundtracks. I made it a point to record live gigs as much as possible. In recent years small independent labels have approached me to issue vinyl which includes the Hipshot catalogue and new recordings. Laurence English’s ROOM40 in Australia, Discrepant in the UK, Ruptured in Beirut, and Sacred Summits are all self-funding, self-organizing labels more preferable to me that I’m happier to work with rather than multi-nationals. They sell everything they make and I keep my rights. Some in the past should be available and are not. ‘Uptown Hawaiians’, ‘Island Songs’, ‘Life and Death in Paradise’—the last of what I consider to be my singer songwriter albums—are all rotting in a vault waiting for me to die probably. The latter promptly disappeared into the cut-out bins until 2000 when someone visited me to re-release it, which I agreed and gave them the test pressings (the masters couldn’t be found). That person still has it and 20 years later has never released it. I made the mistake of signing a contract unfortunately and it remains out of my reach. The other records? Who knows?!

Interested only in creative freedom rather than the banal that the business too often prefers, Mike Cooper still shows a love of traditions (plural) while a maverick enamored by eccentricity or, better said, originality. Rules depend on what alphabet or notation is embraced. Improvisation was always from the beginning integral, indeed organic, to his approach initially explored decades ago on this superb box-set that first set-sail charting a fascinating voyage.

– Brian R. Banks

Mike Cooper – ‘Five Albums On Three Discs’ (BGO Records, 2019)