OSR Tapes

OSR Tapes is a not-for-profit music label that started in 2007, operating for years in Brattleboro, Vermont and later moving to Brooklyn, New York in 2013.

This DIY label released a variety of obscure music that either would be left forgotten, or stay covered with dust.

What is the concept behind the OSR label?

Self-representation / the loving representation of other musicians’ work, that’s all. The acronym originally stood for nothing, but later I favored the backronym open session rock. Having since shed the “rock” component, I’ve been happy to proceed without any overweening conceit, just a little Robert Desnos quote on the return address sticker. But in the interest of having it both ways, I’d cite Wittgenstein: “This is how we do it.”, or Mark Beer: “The small get by.” In any case I’d likely have done none of this without the loving precedent of my friend Jamie Kanzler, who started his own Cats Records Records in 2007.

What are some of the highlights when it comes to OSR Tapes?

That it’s given geographically scattered musicians access to a nice palette of different models of devoted music practice to which to aspire. I’m least proud of my tangled combo of worldly ambition & juvenile acrimony as it has manifested itself in my demagoguery over the years but I can’t fully regret anything that has animated the work: the sanitization of the “negative” is unappealing at best.

You’re planning to close the label?

The label would like to enjoy its peaceful death, unencumbered by ponderous soliloquies or statutory explanations — it’s been dogged enough by its ineluctable relation to its semiocapital nemeses. But with respect to my own work: let’s say a given painter paints paintings and eventually is offered a gallery show. She presents her work at the show and is offered another show. Flash forward ten years and she’s now habitually painting gallery shows, not paintings. That’s my situation … I’ll continue to make paintings and assist others in theirs but I’d like to more carefully avoid painting shows.

How do you see the current alternative scene?

Do you mean the invisible, diffuse one, always vital despite its algorithmic vanishing ? Or the liminal ones like OSR, the poaching grounds for the next darlings of industry, the natural habitat of cake-&-eat-it freedom peddlers like me? Or do you mean the contrived one vaunted by the glossies? My preference is for the invisible, diffuse one, closest to the work itself by virtue of its lack of meditative representation — the rest is suspect.

What are you listening to lately?

Tyler Maxin’s WNYU interview (here) with our friend “Blue” Gene Tyranny … Burnier e Cartier, the new Porest record, Inc. No World, Roxy Gordon, the new Big French & Blanche Blanche Blanche records in the works, The Jepeto Solutions 7” we just finished for Nicey Music in Los Angeles, and the myriad final OSR releases by Tori Kudo, Chris Weisman, Ben Lawless, Flaming Dragons of Middle Earth, Christina Schneider, Marlon Cherry, Frank Kogan, Mark Beer, Ruth Garbus, Black Bananas, Hartley C. White, Gape Room, Al Marantz, William Austin Clay, Matthew Thurber’s Popular Pig, R. Hundro, Jo Miller-Gamble, Jake Tobin, Brave Radar, Salt People, Listening Woman …

Do you collaborate with other labels?

Feeding Tube Records is a solid role model: facilitating and releasing interesting work with hardly any “publicity” angle. But aside from those run by my friends, I don’t really have enthusiasm for the label game. The work itself is what interests me, documented or not, and the idea that the “right art” is important to preserve its way to “society”. There are meanwhile entire languages that are dying out, and whole communities of people, and species of animals, ways of life, natural environments, and actual practices. So it would seem that there are more exigent conservation issues in life than art documentation, one notable one even being the preservation and encouragement of one’s best qualities through the self-work offered by personal practice. Working for a state of affairs where everyone can use art practice for their survival, growth, and communion with each other (rather than in divisive competitions in the Red-Bull-sponsored wrestling rings of semiocapital or as anesthetic diversion from the ritual sacrifices of upward mobility) is something that I don’t think record labels of any size can do as well as other less capitalistic enterprises or even as a benevolent person in their daily life.

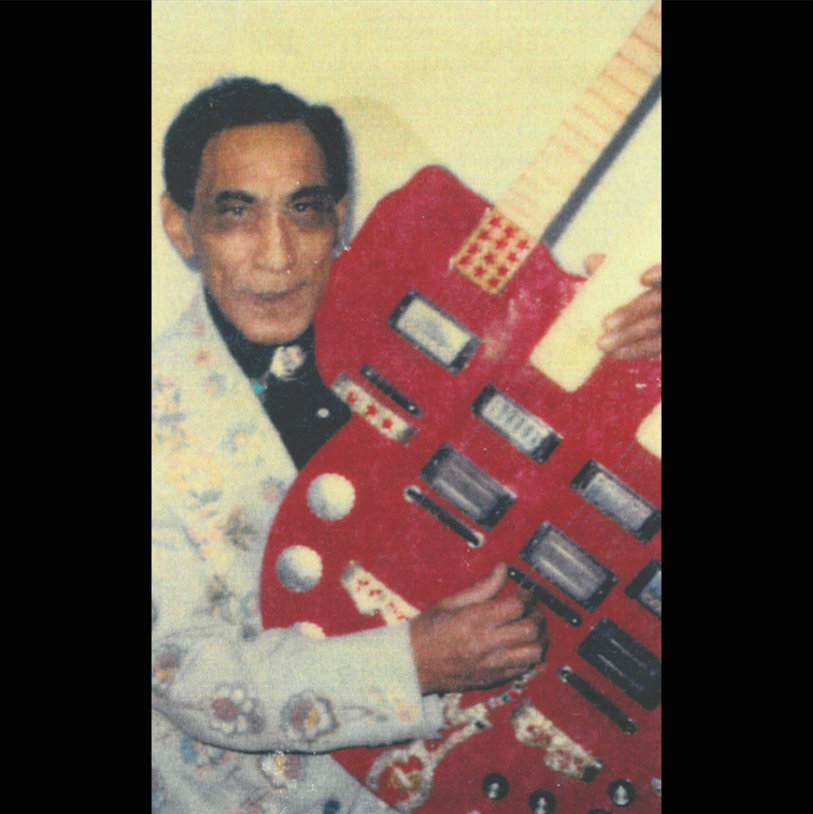

What’s the story behind Jimmie Packard’s release?

Jon Appleton and I were sorting through his old cassettes and I was struck by this strange beautiful man holding an obviously homemade monstrosity of a four-necked guitar: one of Jimmie Packard’s self-released cassettes Jon had picked up at a barn dance in ‘70s Vermont. After contacting his son, I visited the family’s house in Wilder, Vermont — I grew up just a few miles from there — there’s a barn in back where Jimmie would multitrack and cut his own records, teach lessons (he had a lesson-appointment book the size of Weegee’s photo journal), build instruments and rehearse bands. This was a man who gave his whole life to music, and I do hope that more of his mind-bogglingly extensive work is preserved. Anyone with the time, skills, and interest necessary to give Jimmie Packard’s work proper documentation should contact me and I would be happy to put you in touch with his family. But as much as the music lover in me hears the work screaming for preservation, it makes sense that in the laconic, bucolic, unpretentious tradition of rural Vermont, these nutrients might cycle back into the soil sooner than later.

Your very first release is ‘Rebuking The Despoiler’ by Sord. What triggered the idea to release it as your very first album on your label?

Sord was with Sarah Smith — later we called ourselves Blanche Blanche Blanche. I still hear the sweet music in there, the space, the worship of life in the collage of street sounds from Ecuador. In those days “noise” or “collage” were for me shock tactics, ways of trying to get the ears working, listening to life: “wake up!” In New York, the music you hear on subway platforms on the way to a show is typically much more vital than what’s about to happen at the club — even a “bad” busker plays much better, and-for-better, than your average indie. ditto the birds & insects of the hinterlands, the woodland pattering, water on the move. Sound is life, not something to turn “on” & “off” to gild financial transits and schizoid compulsions of identity maintenance.

How do you feel about the vinyl and cassette revival?

In its red-herring-ish emphasis of the physicality of these media, it would seem the ‘revival’ is a sign of the repressed need many people feel for a less mechanistic relation to sound: it’s understandable that the way digital life is always ‘on’ (there’s no ‘end’ to the iPod) makes people want an ‘off’ switch, an end to the tape or the record. But of course this consumer trend is hardly sufficient medicine for what ails its adherents, myself included. Wilhelm Reich: “One can decorate a trap to make life more comfortable in it” … but “the nature of the trap has no interest whatsoever beyond this one crucial point: WHERE IS THE EXIT?”

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Hartley C. White session, 2016.

OSR Tapes Official Website / Facebook / Bandcamp / YouTube