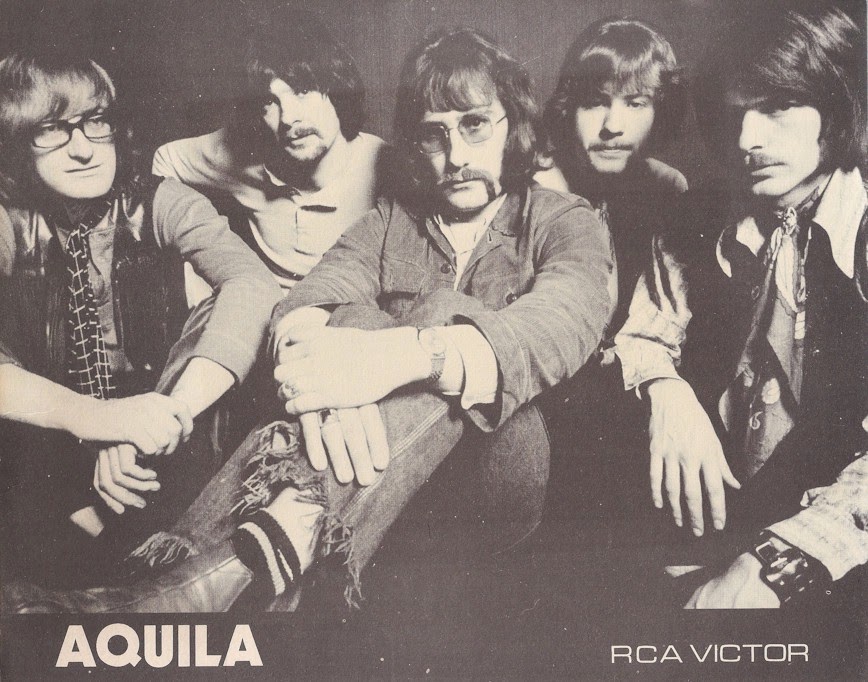

Aquila interview

Aquila were a five-piece progressive rock band from the UK who, in their time together during that wonderfully creative and burgeoning prog scene of the day, sadly left us with only one 1970-issued, self-titled release on RCA. Flute, sax, and the venerable Hammond augment the classic bass-drums-guitar bedrock, affording a jazz-inflected sound not too dissimilar to the output of the Neon, Dawn, and Transatlantic labels at that time—think Raw Material, Diabolus, Tonton Macoute, or Hannibal.

Read on as Martin Woodward (Hammond) and James Smith (drums, percussion) share all, from the band’s beginnings, vividly-recounted and humorous accounts from ‘on the road’, to Aquila’s stifled potential.

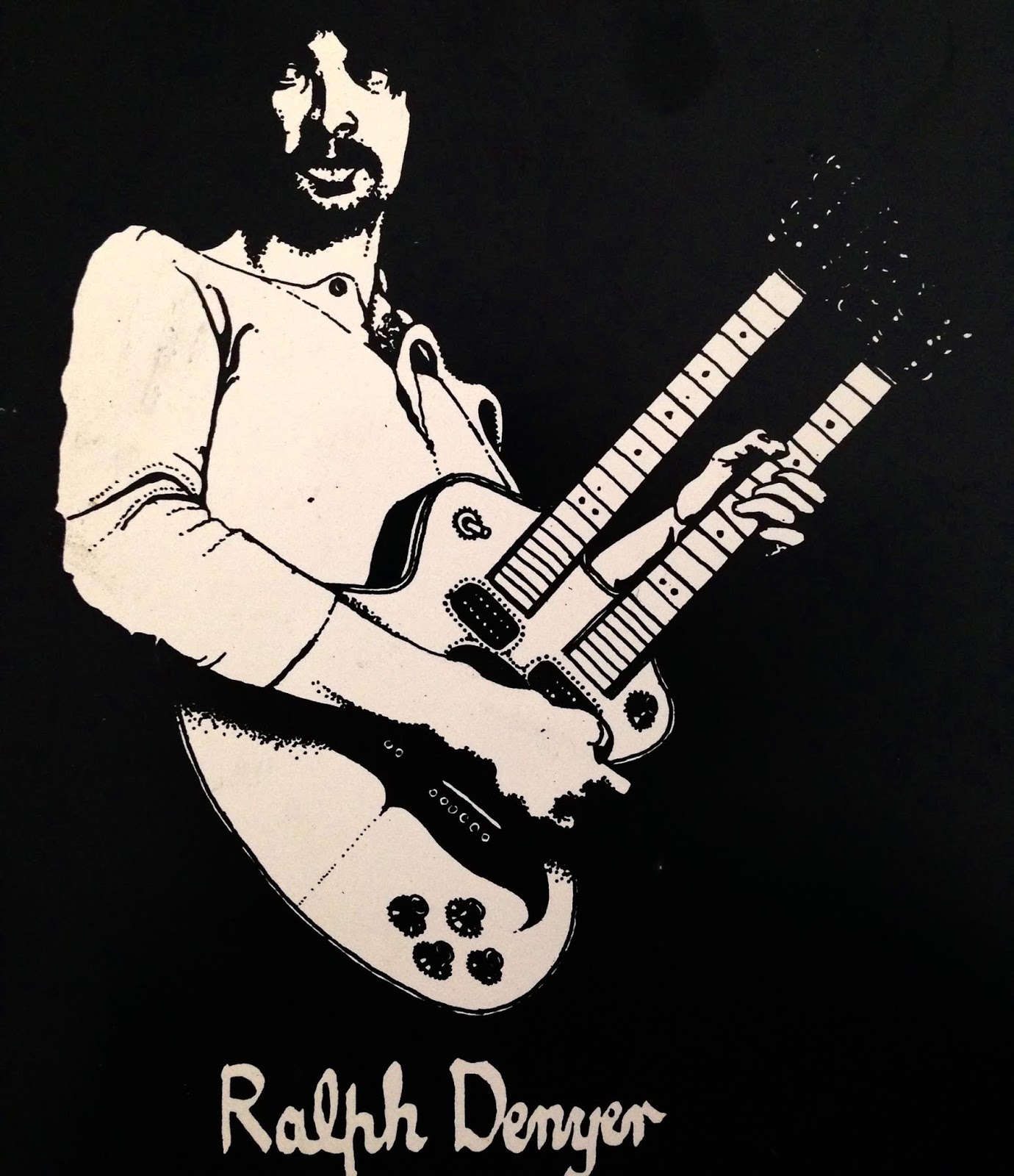

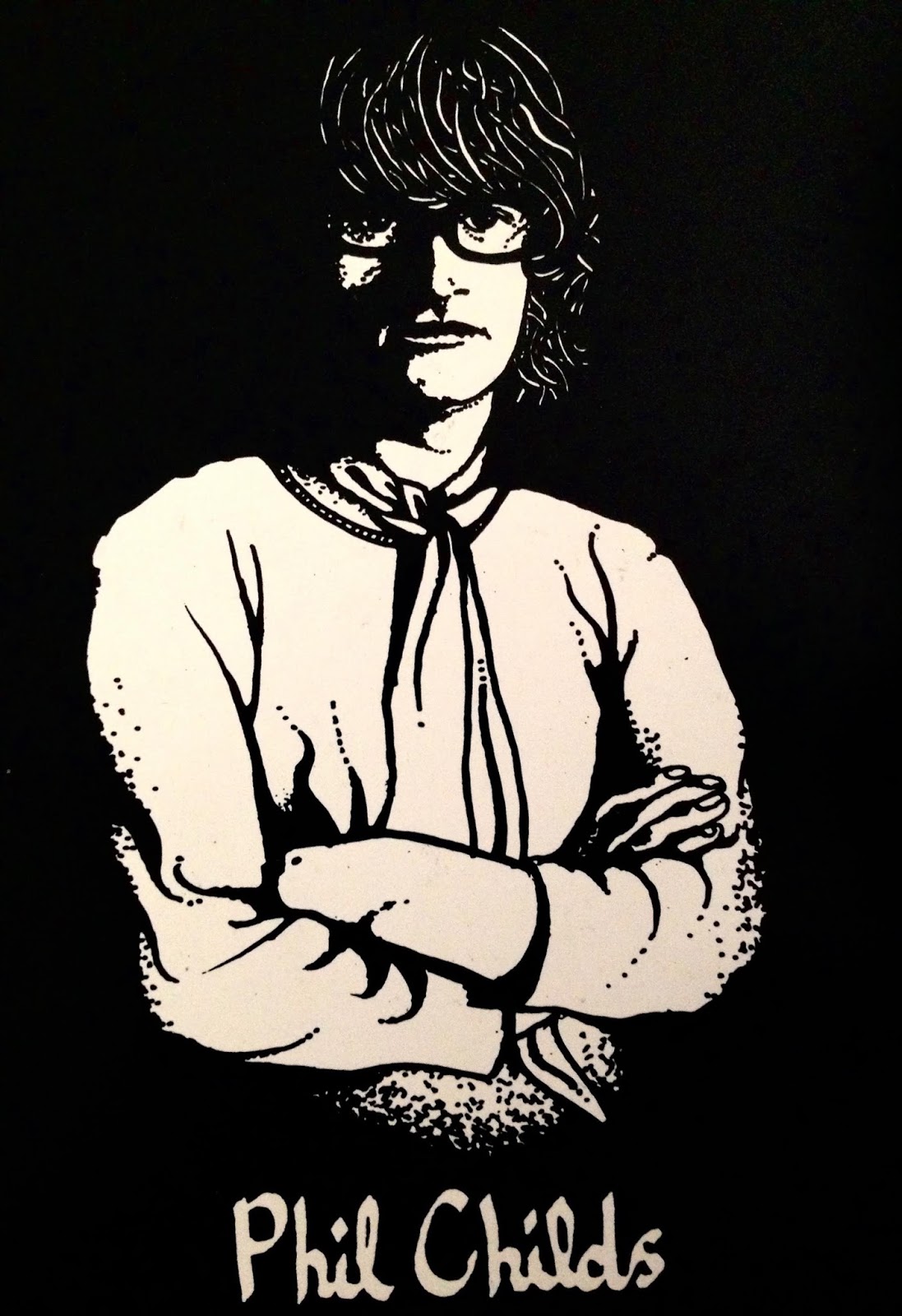

Aquila were:

Ralph Denyer—Vocals, electric & acoustic guitars

Phil Childs—Fender bass, piano

George Lee—Flute, alto, soprano, tenor & baritone saxes

Martin Woodward—Hammond organ

James Smith—Drums, timpani & various percussion

Where were you born and could you share some of your favourite bands growing up? When did you start learning piano/keys/organ and who were some of your influences? Did you play any other instruments before picking up the keys/organ?

Martin: I was born in London in 1949—although I am half-Welsh (my mother)—and also the youngest band member. Many write-ups about Aquila have suggested that we were a Welsh band, which is incorrect (and must have annoyed the pants off the others)—I am the only Welsh connection. Ralph Denyer’s previous band, Blonde on Blonde, was predominantly Welsh, which is no doubt where the error came from.

I started learning the piano aged about 6. My greatest influences were jazz organists: Brother Jack McDuff and Jimmy Smith—also Graham Bond.

My favourite bands when growing up were The Shadows, The Graham Bond Organisation, The Animals, The Zombies, The Moody Blues, The Pedlars, and The Yardbirds—plus, of course, The Beatles and The Stones. I had the very great pleasure of attending Led Zeppelin’s very first gig in the Marquee Club, London, when they were originally called The New Yardbirds. Back in those days you could have ringside seats to see great bands for peanuts!

I tried playing drums briefly as a teenager but dropped them as I was crap—and there was more demand for keyboard players.

Immediately before Aquila, I was working with James in a soul band called The Fantastics. We split to form Aquila with Phil—who had previously worked with James—and we found Ralph via an advert in the Melody Maker. George came along a little later.

Could you tell us a bit more about The Fantastics? Was that the first band you were in and were there any others pre-Aquila? Please feel free to go into as much detail as you like—band members, fond memories, etc..

Martin: After numerous semi-pro London bands, my first professional band was called Tapestry, who made a couple of singles, but didn’t do a lot. While I was with them I met Pip Williams (by chance)—who was the guitarist with The Fantastics—and he got me the gig with them (where I met Jim). The other member of The Fantastics band was Ron Thomas on bass, but I don’t know what happened to him.

Pip went on to become a top record producer for Status Quo, Barbara Dixon,…and was the brains behind many huge-hit records including “Kung Fu Fighting” (by Carl Douglas).

Getting to the formation of Aquila…You met James via The Fantastics, Phil knew James, and Ralph came on board via a Melody Maker ad (after having been in Blonde on Blonde). You mention George “Snakes” Lee—on flute and saxophones—joining a little later; could you elaborate on that (and on the “Snakes” nickname)? How were the first few practice sessions? Did it take long to settle on the type of music you wanted to play? Ralph is credited as sole composer on the back cover of the LP; did it take long for the songs on the album to take form?

Martin: Although George was the last to join Aquila, it was still very early on and only a few weeks after we started rehearsing. Initial rehearsals with Aquila went great, but it was clear from the outset that something was missing—hence George who we found via the Melody Maker. George fitted like a glove immediately. Before we even began rehearsing it was clear that we were all in the same musical ‘groove’.

Having completed the line-up, we initially got a set together using our arrangements of ‘cover material’, which to be honest was good stuff and I wish we could have kept some of it in our act (but I got voted out on that one).

Then we went to Rome for a month and worked in the Piper Club—which curiously is still there—under the name Tapestry, where we worked on our material for the album.

It’s true that Ralph wrote the material, but the arrangements were very much a group thing. Other editorials about Aquila suggest that Ralph was the ‘leader’, which was rubbish. There was no ‘leader’; everything was democratic and there were few arguments.

We later went back to the Piper Club in Rome as Aquila, doing entirely our own material.

I never knew George as “Snakes”. I’ve no idea where he is now and would love to find him. I’ve read that he joined a group called Arrival, but have seen no pictures to confirm that it was actually him or not; there was another George Lee saxophonist on the scene and they may have got confused.

You’ll probably never find George—although I hope you do—but I can tell you that he was a big John Coltrane fan and more of a jazzer than anything else. He was married to a lovely girl called Sherree—probably spelt wrong—who was half-English and half-Indian. George was really a ‘home bird’ and not really suited to life on the road, so I guess he ended up playing in local jazz bands (but I could be wrong).

James: So, just to say I would concur with Martin regarding the formation of Aquila, except he is being a little modest. Actually, the existence of Aquila is entirely due to Martin and myself. When we were with The Fantastics we formed a genuine friendship. Also, musically, we were very compatible—very much into jazz-rock. We generally roomed together on the road and often talked at length about music and original arrangements etc.; I remember us discussing creating an instrumental version of “MacArthur Park”.

Anyway, when The Fantastics went back to the US, we were out of work. Martin was crashing at my flat in Ealing, and it was almost an unspoken understanding that we should try to create something ourselves, rather than just look for another gig. I mentioned that I knew a really good bass player of a similar musical leaning, and if he was free we could get together and see what happened. Luckily, Phil (Childs) was indeed free, so we arranged a rehearsal room; within half an hour it was as if we’d been playing together for years, so we all decided to give it a go.

None of us could sing, so we advertised for a guitarist/vocalist and were lucky enough to get Ralph, who again fitted in seamlessly—as did George a little later, as Martin said. Also, me too regarding the “Snakes” nickname; I’m sure it wasn’t our George. I think that maybe he is getting confused with the Ghanaian jazz tenor player, George Lee?

Regarding the compositions on the album, I would go further and say that we, as a band, didn’t get nearly enough credit for the material—no one to blame, just the way it turned out. Ralph would come up with some lyrics and a very basic chord sequence—nowhere near what you could call a finished piece. We would then build on that as a team—each of us adding according to our skills—with the end result being very much a product of our combined ability.

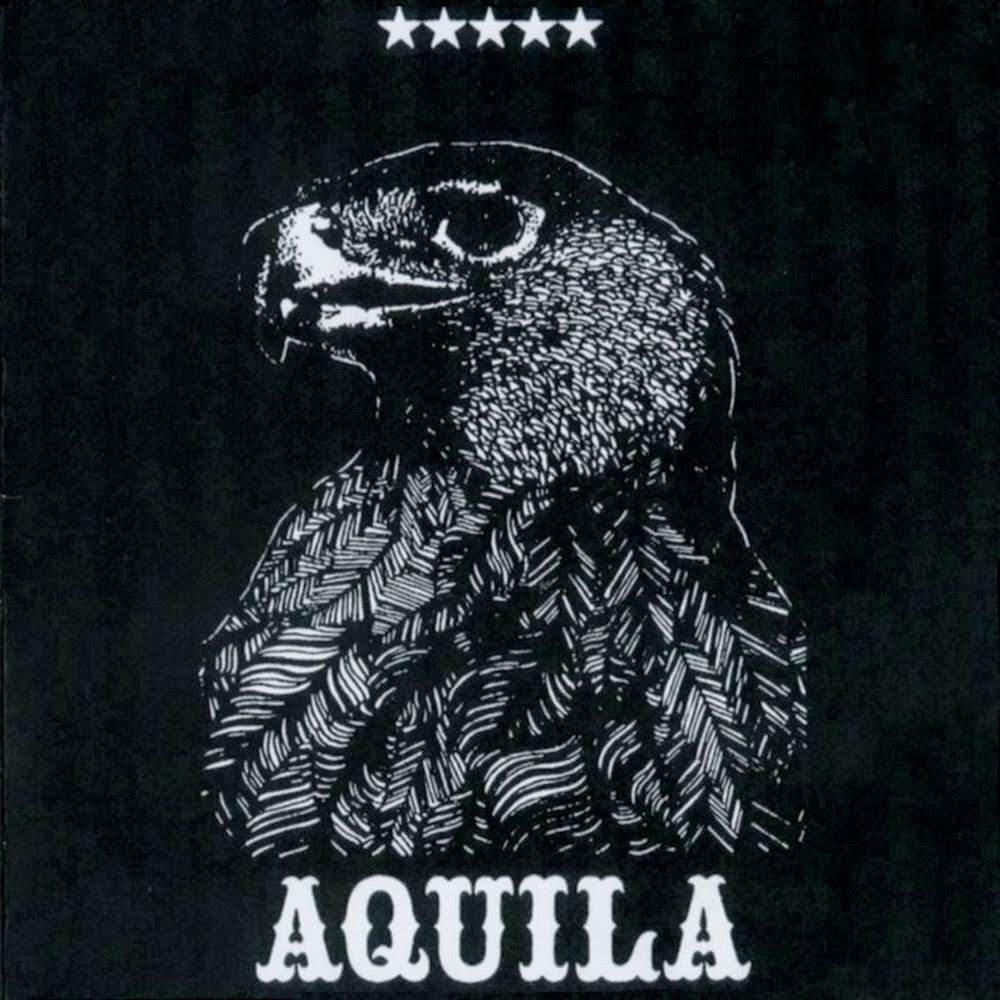

How did the band name “Aquila” come about and when and where were you spotted by RCA?

Martin: We toyed with lots of names and were almost going to be “Animal Farm”. As you probably know, “Aquila” means “Eagle”, as well as a star structure. I can’t remember who came up with the name originally—it wasn’t me—but we all liked it, and even now I think it’s a great name. I loved the album cover, which was in fact a drawing of Goldie, the golden eagle who, at that time, was in London Zoo and quite famous. Keith, who did the drawings on the album, was a friend of ours.

We did originally want an eagle’s cry at the beginning of the album, and Ralph went to London Zoo and asked the keeper if he could take some recording gear there to record Goldie. The keeper said, “You can try if you like mate, but I’ve been here 30 years and haven’t heard him make a sound yet!”, so we gave up on that one!

Can’t remember when exactly we got the deal with RCA, but we were in negotiations with a few record companies and they were the first ones to cough up some money in advance. With me being the youngest, I just went with the flow.

James: What I remember (somewhat hazy) about choosing the name: Initially, we couldn’t remotely decide on anything; we did the first gig at the Piper Club in Rome using the name of Martin’s old band, Tapestry, who I believe had ceased to exist. We subsequently had almost decided on “Animal Farm”, which we had all agreed on—but not with much enthusiasm, it has to be said. At the time, Ralph was living in a house share in Hendon. Alistair, the owner, was really good to us, and had virtually given us his large lounge to rehearse in; it became almost like a second home to all of us. I remember being there after rehearsal one evening with Ralph, Alistair, and a couple of the other housemates; I’m not sure if Phil was there or not, but I think Martin and George had left. Anyway, we were all smoking weed and generally talking rubbish, when the topic of the band’s name came up. One of the guys (can’t remember his name) who was into astrology suggested that rather than name the band after a ‘somewhat depressing’ book, why not name it after a star or constellation. Out came a book, and we came across the name “Aquila”—a constellation which was also the Latin for “eagle”. It was prominent in Roman mythology as the sacred bird that carried Jupiter’s thunderbolt. It instantly appealed to us and at rehearsal the next day we all decided to adopt it.

Moving on to the album. Firstly, why sign with RCA? In hindsight probably not the best decision, but they were the only ones that offered a cash (non-returnable) advance. On the surface that sounds a bit mercenary, but it has to be remembered in the context of the times. Like Martin rightly said, we had to earn a living, and although we were a very good band, we weren’t really earning what we deserved. We weren’t alone! At that time, musicians—the people creating and delivering ‘the product’—were right at the bottom of the ‘food chain’. The whole industry was infested with ‘middle men’ who did nothing except feed off the talent and hard work of others. Even though a venue might pay a fair amount for a good band, it would probably have gone through several promoters/agents who would all help themselves; by the time it got to us—and we had shelled out for transport and accommodation—it often didn’t amount to much to split 5 ways. Then of course supply and demand was a factor; there were so many bands around [that] promoters had the attitude, “If you don’t want to work for peanuts, we’ll soon find someone who will.”. Even hit singles weren’t a guarantee of a decent living; The Small Faces, among others, would certainly testify to that.

Could you talk about your experience recording in the studio? Was this your first time in one? Do any particular memories spring to mind? Were there any tracks you played live that you wish had made it onto the album?

Martin: We’d all recorded before, but for me it was the first album. I’m not sure about the others, but I know Ralph had done a previous album with Blonde on Blonde.

I can’t remember the name of the studio, but I know it was a new one at the time on the Old Kent Road and was one of the first to have a 16-track mixing deck.

I personally would have liked to have included a couple of ‘cover’ tracks—which we did bloody well—but as I said before, I got voted out on that one! Also, a bit more instrumental stuff, which we were good at.

Beyond that, I would have liked to have re-recorded my solos—which make me cringe—but everyone else said, “Oh, they’re alright!”. But all of our (mine and George’s) solos were always entirely improvised and never the same twice, and how good they’d turn out were entirely dependent on how the band gelled together. If Jim and Phil (the driving force) were having a good day, then my solos would sound fantastic; if they were playing crap, then so would I. Everything that Jim said was correct: No one in the band was carried; every member was the most important!

And I, with knowing what I know now, would have mixed it all differently. Right now I’m learning Sonar X2 (just got X3 but not loaded it yet), and I’m utterly amazed at how different you can make stuff sound by re-mixing and messing with the EQ etc.—and I’m only using 3 tracks (keyboard, bass, and drums).

Although I loved Ralph and what he did, he was NOT a lead guitarist, and in my opinion some of what he did (on the guitar) was too prominent on the album—but I loved the songs and his vocals!

Also, what Jim said about the rest of the band not getting enough credit was correct. Not to take anything away from Ralph, but it was very much a joint project. In fact, I remember Jim talking about how he would like to end the album before we even met the others; the timpani and tubular bells at the end—which should have been increased in volume on the mix—and general feel of the track were Jim’s idea from way back.

James: Martin’s comments regarding recording with Aquila brought back a flood of memories, and also a degree of frustration.

After signing the contract, we were assigned Patrick Campbell-Lyons (ex-Nirvana) as a producer and an American employee of RCA, Lou Reizner, as executive producer (i.e. holder of the purse strings). The studio we used was Manfred Mann’s new premises in the Old Kent Road. I don’t know how that was chosen, but it was a new 16-track setup—and probably as good as any. Patrick seemed to know what he was doing, but throughout the sessions there seemed to be a lot of pressure on him to get it done. Martin mentioned he would have liked to have re-done some of his stuff; I think there were quite a few things we would all have liked to re-do, but there was a lot of “It’s fine. It will do.” noise from the production team. As for the final mix, this was done by Patrick, Lou, and Ralph; the rest of us had no involvement whatsoever, and it has to be said the result was a little disappointing. Martin’s comment regarding Ralph’s guitar playing and prominence on some tracks is spot on. Also, I had always found his timing a little suspect at times. I never mentioned it as his other contributions were so valuable and on stage it didn’t really come across, but on the album it is noticeable.

Regarding the content, Martin is right in saying that we did some really good cover versions in our own style, and some of our instrumental stuff was of a very high standard. I could be wrong, but I seem to remember that it was part of the RCA contract that the album would be 100% original material; it was pretty much obligatory at the time.

“We also worked with David Bowie somewhere else.”

Are there any gigs or memories from touring that stick out for you? We’d love to hear any!

Martin: There were so many memorable gigs: Certainly both times we worked at the Piper Club in Rome and also the Paradiso in Amsterdam were pretty amazing, but there were so many great times and great memories which I’m truly thankful for. Although we were always skint, they were the very best of times. Other great gigs were Leeds Uni, Exeter Uni, and the Country Club West Hampstead, where we supported Elton John. We also worked with David Bowie somewhere else. The Roundhouse Chalk Farm was another great gig, and also the 1970 Plumpton (open air) Festival. Funnily enough, another really memorable, great gig was when we worked in a Chinese restaurant and there were about six people in the audience—but it was great!

George had an amazing habit of shouting out “Hey!” (hay) every time we drove passed a haystack. I adopted this habit and still annoy my wife the same way! He also collected cigarette vouchers, although he never smoked. He used to pick up all the empty cig packets at the end of every gig and collect thousands of vouchers left behind. One day I saw him throw down an empty packet in disappointment, and a guy came up to him with a cigarette and said, “Here you are mate, have one of mine!”.

Anyway, here’s the Roman story:

After having completing our line-up and initial practice sessions, we got a set together consisting of mainly covers and went to the Piper Club in Rome in late 1969, for a month, to earn a few bob—and also work on our own stuff ready for the album. Curiously, it’s still there and still called the Piper Club.

First thing, we needed a van—preferably one that cost nothing. Jim managed to acquire an old, small removal van with a Luton cab (bed over), where we put a mattress to take turns at sleeping. Now, back in those days, heaters in vehicles were an optional extra; we didn’t have one, so it was a bit nippy going over the Alps, but it got us there.

Now I don’t know whether you know about this or not, but in those days going through France with musical instruments was a no-no as you had to have a ‘carnet’—which involved paying a deposit of 50% of the value of the equipment, which all had to be checked and accounted for etc.—as it was all worth much more in France. As we never had that kind of money, our route to Italy was Belgium—Germany—Switzerland—Italy—no problem!

Anyway, we did the gig—which was great—and we had a great time in Rome, but as winter was setting in, there was no way back over the Alps except through the Mont Blanc Tunnel into France! So, we thought we’d risk it. Jim and I had previously worked in France with The Fantastics earlier in the year and got in from Germany without a carnet, so we thought maybe they wouldn’t notice that we were English—as if!

As we had to come back through France, our agent arranged us some gigs in Paris on the way back, and we had instructions to meet M. Jean Bernard in a café in Paris about 24 hours after leaving Rome.

Anyway, when we arrived at the opening of the Monte Blanc Tunnel after having left the Italian border, unsurprisingly we were stopped for the carnet. The money that we all made in Rome was nowhere near enough, so we hung around for a bit and tried negotiating, which was quite difficult as we didn’t speak French and they didn’t speak English. Also, by this time, it was freezing cold and belting it down with snow. Our next line of action was to go back into Italy to see if we could find an alternative route, like a smaller, more difficult crossing. Jim could do it; he could do anything! But at the Italian border they decided that they also wanted a carnet; normally the Italians didn’t bother about such things. So we were stuck in no man’s land between the two borders, and it was getting colder and the snow was getting deeper—and of course we had no heater. I actually didn’t think it was possible to be so cold and still alive! But we managed to refrain from huddling up to one another to share body warmth—that would have been a step too far!

Then we tried phoning the British consulate in Turin. They weren’t much use; they just told us to dump the gear on top of the mountain and go home without it. My organ cost me a bloody fortune and I hadn’t even half-paid for it, so that wasn’t an option. Even if the others had decided to do that—which they didn’t—I would have stayed there and died with my organ!

By then, night had turned back to day and it was getting even colder—if that was possible. Ralph had a sleeping bag which we shared—one at a time—to keep the blood from freezing!

The customs men had three eight-hour shifts and we tried each one in turn to see if one was more understanding of our plight—but they weren’t. Each shift was as miserable as the last! It was 1969, only 25 years after we won the bloody war; you’d think that they might have been at least a little compassionate! I remember Phil—who could speak a little French—was pleading with them on the grounds that we all had mothers worrying about us, but his French wasn’t that good; he was probably accidentally calling them a bunch of mother fuckers! He might as well have been for the good it did!

Anyway, after we’d tried all the shifts and it was night again, we thought that, as we’d been there that long, that they’d hardly notice us if we coasted into the tunnel quietly with the engine switched off. Worth a try, as it was downhill and the barrier was open! Well, we got about 25 metres and they started firing warning shots at us. At least I think they were warning shots, but we thought we’d better stop and see what happens next.

Well, we got a heavy on-the-spot fine for that and, surprisingly, they arranged us a carnet for a reduced deposit, which was still a substantial amount, and was more or less every penny we had (barring expenses) to continue.

At last we were free and we’d got into France. I’ll never forget the first village the other side of the tunnel is called Les Houches. We stopped there in the snow at a little skiing hotel which was still open at about 3:00am and we had jambon sandwiches and black coffee. I don’t even drink coffee—especially black—but I remember that tasting better than anything before or since, as I was that cold and hungry. And we got such a warm welcome there, just after I was cursing every Frenchman and swearing I’d never set foot in the place ever again.

Next stop: Paris. But we were at least 24 hours late. We thought we’d go to the cafe just in case Jean Bernard was still there. Well he was. And very disgruntled. He just got in the van and said,

“I av zee gig, you are not ere—vot can I do? Fuck zem, you know. Zis vay, zis vay.” (French accent and lots of Gaelic shrugs; you can probably do it much better than me!).

We said,

“Have we got a gig or not?”.

“I av zee gig, you are not ere—vot can I do? Fuck zem, you know. Zis vay, zis vay.” (more gaelic shrugs).

“For you, I av zee competition. If you win, you get paid. If you don’t…(big Gaelic shrug). Fuck zem, you know. Zis way, zis way.”, continuing to give directions to goodness knows where.

“Listen”, we said. “We’re not working for nothing—we’re professionals!”

To which the reply was,

“Don’t vorry, don’t vorry. I am zee judge. Fuck zem, you know. Zis vay!”

We finally arrived at some crappy little French club which was about three floors up. So we all walked up the stairs to see if it was worth getting the gear out.

“You bloody Engleesh, you all ze same. You av all zis gear and you valk up all zees stairs and you CARRY NOTHING!”

“Listen man, give us a break. We haven’t slept for 3 days!”.

“But I av not slept for 20 years!” (big Gaelic shrug).

Apparently he was an insomniac and never slept—probably all that French black coffee!

We eventually dragged all the gear up the stairs and won the competition (unsurprisingly). But our winnings were about half of what we should have got paid anyway, and the hotel was supposed to be paid, but it wasn’t—big rip-off! And by today’s standards, health and safety would certainly have closed the hotel down ten times over!

We were assured that things were going to get better, but we just knew the guy was a crook. The next gig was in a plush château. I think it was a four-year-old kid’s birthday party, and he’d been put to bed so that everyone else could get pissed. Well the gig went fine, but again we didn’t get paid the previously-agreed amount.

At the end of the gig Phil and I noticed a red-hot storage heater in one of the back rooms, and we decided to nick it to try and warm the van up a bit. So we unplugged it, chucked a speaker cover over it, and struggled out with it unnoticed—bloody heavy, as it was full of bricks! When we got it to the van, we found that the others had been pinching loads of silver; don’t judge us, we were starving musicians who’d just been ripped off! I’m not sure who nicked what, but the stuff was everywhere; it was like Ali Baba’s cave in there!

But then Jean Bernard decided he wanted a lift back into Paris, so we hurriedly chucked all the booty onto the mattress above—the heater included—but it caught fire. Jim was driving, with Jean Bernard sat next to him saying, “Vot is zat smell?”, while the rest of us were beating the flames out!

It was a relief when Jean Bernard got out. Then we managed to get things back to normal in the back of the van. The next night we did the last less-eventful French gig, but then we realised that we had to have the van checked at the customs to get our carnet money back and we’d got all this ‘loot’. Unfortunately, we decided that it had to go, so we dumped it in someone’s dustbin after the gig, on the way back to the port. I have a vague memory of a little old lady giving us the thumbs up as we were sticking the stuff in her dustbin, but I’m not sure whether I dreamt that or not.

At the port we did fortunately get most of our carnet money back. Jim commented recently that the look on the custom guy’s face was priceless when he saw how much they had to give us, and they had to raid a cash machine to get enough money for us—I must have been asleep then.

It’s a fantastic memory which I’m so grateful to have.

It would be great if you could say a few words about each song on the album, for instance anything you can remember in terms of each song’s construction and other interesting facts (such as how James wanted to end the album with timpani and tubular bells).

Martin: I’m not going to be much help here as the memory is failing a bit, but basically most of the songs were constructed by Ralph coming up with the original idea and getting us all to play along with different rhythms. This created more ideas between all of us, and the songs evolved that way.

My favourite tracks are “How Many More Times” and “While You Were Sleeping”, which is one of the tracks where George and I did riffs in harmony—and this created the Aquila sound. I also had the Hammond running at half speed on that track, which created quite an interesting sound. I also very much like the ending, which I’ve said was entirely a joint creation.

Jim’s idea about the ending originated when we were with The Fantastics and very much into the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, which used the timpani at the beginning when the apemen were jumping around the monolith that arrived from outer space. We often had the privileged of passing Stonehenge early in the morning—just as the sun was coming up—and we used to play monkeys around the stones (before they put the fence around them). In fact, we were probably the reason that they put the fence round them!

Could you say a bit about how and why Aquila disbanded?

Martin: Aquila didn’t so much disband as fell apart. No one actually said, “Right, that’s it. We’re done.”. RCA didn’t do anything for us, and the main reason it fell apart was lack of funds, or rather lack of gigs (which amounts to the same thing). But I was always hopeful that it would all get going again.

James: I don’t know if Martin would agree with this but, from my recollection, I felt that the main reason was that we simply lost the enthusiasm. Yes, there were some contract issues regarding Ralph and RCA [but I don’t feel like they were the main reason]. We had all put a hell of a lot of effort and hard work into the material and the album itself; when it didn’t take off, it was very disappointing. The production was not as good as it could have been and RCA did virtually nothing regarding promotion. Though nothing was said directly at the time, we just seemed to lose the impetus. In hindsight—a mistake; we should have learned from the experience and stuck at it.

Martin: Jim is certainly right about the fact that RCA did nothing for us—I guess we were just tax loss! We were a good band, but just not getting the gigs that we should have had. To be honest, I’d previously earned a lot more money playing in crap semi-pro bands—such a shame. We weren’t greedy, but we did need to survive! But that’s life!

James: There was no specification regarding a promotion budget and no provision for releasing a single; a 3.5min version of “The Hunter” and “How Many More Times” for a B-side would have been a respectable offering—in my opinion, anyway. Finally, and most significant, was that it was only for one album. Had it been for two—which I pushed for at the time—I don’t think we would have lost the enthusiasm as we did, and we would have stuck together, learned from the experience, and who knows where it may have led.

In spite of that, the album was quite well received in some quarters; it got a lot of exposure on Radio Luxembourg, and later on became somewhat of a collectors’ item in the genre of ‘70s British prog rock. I’ve heard that an original vinyl in mint condition was fetching $150+ around 2000/2001.

Could you tell our readers what musical outfits you were involved in after Aquila, and are you still active musically today? If so, we’d love to hear about some of your projects!

Martin: After Aquila—and in order to eat—I got a job driving a taxi for a while, then Jim and I worked briefly with Geno Washington (which I can’t say that I enjoyed—no disrespect to Geno or the other band members). I then went on to work with The Tommy Hunt Band, where we also did TV and recording work for Emile Ford. He was trying to make a comeback; he had the first UK No.1 of the ‘60s with “What Do You Want to Make Those Eyes at Me For?”! With Tommy, we were mainly working up North, and it was mainly cabaret, which meant we were working every night (but a week in each venue—pretty easy really) and for once I was actually earning really good money. Other band members there were Tex Marsh on drums, Roger Flavell on bass, and Kevin Fogarty (sadly now passed on) on guitar—all superb musicians. Although The Tommy Hunt band were bloody good and I had a great time with them, Aquila was still haunting me.

Some of the pranks that we used to play on one another are outlined in my book, The Golden Sphere, which is both totally stupid and serious at the same time! Busby the Bear is Kevin, Tex the Bear is Tex, Wriggly the Bear is Roger, Pippo the Clown is Pip, and I’m Bonjo. Download link.

Whilst with Tommy, I met my wife in Sheffield (who I’m still with over 40 years later). Sadly I left Tommy as they were due to do a long tour down South, and I didn’t want to leave the wife. Actually, it tore me apart and was a very difficult decision. The band were literally begging me to stay with them—and they were a great band—and my wife was begging me to leave.

Anyway, I stayed in Sheffield and then worked in a small club/restaurant for a while, where I eventually ended up backing strippers (there’s a few funny stories there as well).

Then I eventually fell into driving instructing, which I did for over 30 years. Not playing music really depressed me, and I didn’t touch a keyboard or ever listen to music for over 10 years as it upset me so much.

At age 54, I sold the driving school and we retired to Cyprus, where we had a lovely villa with pool and all the trimmings. Whilst there, I played the keyboard in a really nice restaurant (on my terms) called the Almond Tree in Paphos.

But Cyprus is bloody hot and I couldn’t stand it, so we returned to the UK and toured Europe in a motorhome for a year, before finally settling in Lincolnshire, and then eventually back to Sheffield.

Right now, I only play the keyboard for my own amusement, but I am writing tunes and my music books. I’ve just put my keyboard up for sale in order to buy a keyboard workstation, which will enable me to record better and easier than I can at the moment—so watch this space!

The download link for my latest keyboard book is.

Could you sum up your feelings about your time with Aquila and the band, looking back at all of it now? Also, the last word is yours, if you wish to say anything to fans new and old, etc.—that sort of thing!

Martin: Looking back at just about anything and everything, given a second chance, we’d all do stuff better, and that’s certainly my feelings about the Aquila album. But it was 45 years ago, and technology is in another world now. But having said that, I’m sincerely very grateful and privileged to have had the experience of the music—and the friendship—with Aquila.

It was certainly one of the best times of my life—despite the fact that we were all perpetually skint—which proves that money isn’t everything, by any means.

I’d like to thank all the other band members and Alistair—who owned the house at Hendon where we rehearsed—for the fantastic memories, and everyone who ever bought our album or listened to it or came to see us. Sincerely—thanks! And thanks to you, Sébastien, for rekindling all these memories and relighting my fire!

Looking at other bands from that era who made it big, in many cases that’s when the rot sets in and things become much too business-like and friendship goes out the window. Look at Procol Harum: The original three were initially all mates together; 40-odd years on, they’re arguing about royalties! I’m glad we never had such problems; we just had the fun and became ‘rich’ in other ways!

James: One of the best things about Aquila, for me anyway, was the way that we were all so like-minded—all of us pulling in the same direction and giving 100%. There were no passengers, and I don’t remember any significant disagreements.

– Sébastien Métens

I was a friend of singer/guitarist Ralph Denyer many years later. He played me the album – as well as the debut by his earlier band, Blonde on Blonde – one of the many times I visited him in Hendon. (The same house mentioned in the article, in fact, where he lived until around 2010!) At some point in the late seventies he left his music career behind and switched to writing about guitars and music technology, authoring The Guitar Handbook, which was hugely successful and very much the "Play in a Day" of the 1980s. I actually first met him in the 1990s when my first ever job as an editor was to update that book. We stayed friends after that right up until he passed away in 2011. He was a good guy and was definitely proud of his involvement with Aquila. (I remember finding an unauthorized German CD release of it in about 2000 and buying it for him.) Just a few thoughts there. Terry Burrows, February 2018 (www.terryburrows.com)

Hello. My father George Lee passed away recently. I’ve been looking for any information about his musical past. It was a joy reading though this article. If you need to get in touch feel free.

My deepest condolences.