Hayvanlar Alemi interview with Işık Sarıhan and Özüm İtez

Hayvanlar Alemi’s sound is so varied that it’s difficult to even really start getting into it. Over the years they’ve carved out a niche for themselves, mostly amongst fellow instrumental psych and rock enthusiasts and they’re based around a strong and proud tradition of improvisation as well, which lends a certain air of psychedelia and experimentation to their music that’s pretty well prevalent throughout their entire catalog.

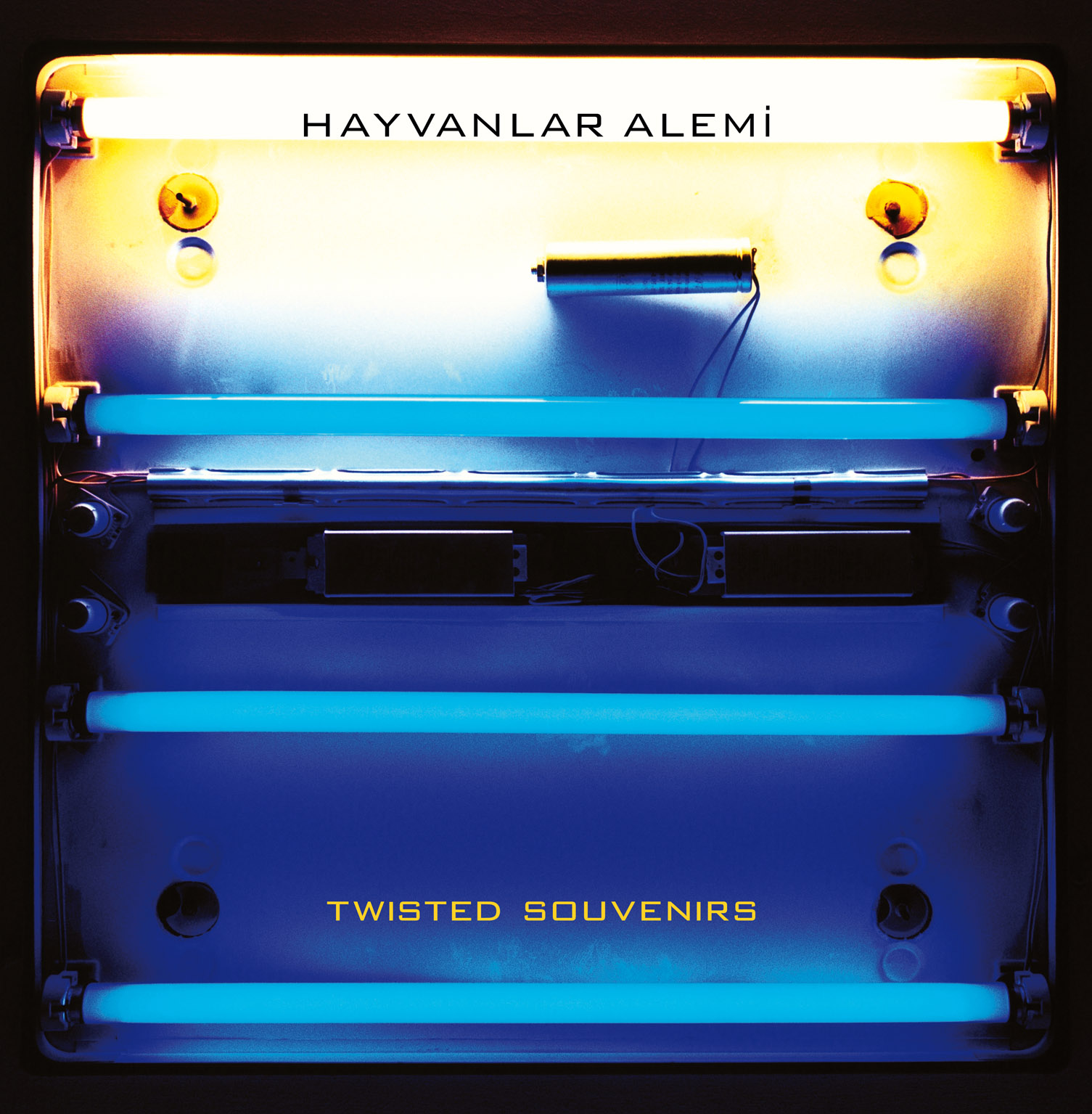

There’s something different about Hayvanlar Alemi that I couldn’t quite put my finger on though, it wasn’t the slight tinges of hardcore instrumental surf or the wide array of psychedelic influences that caught my ear, it was something else entirely, something I couldn’t quite put my finger on. Turns out they’re extremely interested in traditional music from all over the world and incorporate the different sounds, scales and ideas they come across into their music to varying degrees throughout their back catalog, producing an extremely interesting, varied and unique sound that’s difficult to match or compare. I only recently discovered their music and have been particular captivated by their latest offering, 2014’s Twisted Souvenirs 12-inch for the Unrock Records label. The songs on Twisted Souvenir seem like they’re a little bit darker and heavier than their earlier offerings. There’s a fuzzy reverberated edge to everything on Twisted Souvenirs and absolutely no pretense of attempting to cling to any certain genre or sound, not that they’ve ever fallen pray to that before, they’re just doing their thing and letting the tape role while they do. Outside of certain psych connoisseurs like Permanent Records here stateside I haven’t heard a lot of people talk about Hayvanlar Alemi and that kind of surprises me to be honest. They have just the right combination of traditional classic psychedelic rock and brazen bold new compositions, shattering preconceived conceptions of how a song should be structured or what it should sound like, bringing sounds from all over the globe into play with ease; a sort of conundrum wrapped in an enigma stuffed in a box of mystery. Fortunately I got the opportunity to talk shop with two of the founding members Işık Sarıhan and Özüm İtez about all things Hayvanlar Alemi and what follows is one of the coolest pieces I’ve had a chance to work on since I started writing for Psychedelic Baby. I suggest you brew up a cup of coffee or crack a beer, kick back and just let this one digest. There’s gonna be something in this for everyone, even veteran fans are going to find out something new here I feel. I suppose it doesn’t matter either way, as long as the word gets spread the world hears the good word of Hayvanlar Alemi!

I know you all have been around for a long while at this point. Is this your original lineup or have you all gone through any changes since you started?

Işık: It’s almost the original lineup. Özüm, Hazar and I have been playing since we formed the band. We had a different bass player for a couple of years in the beginning, İnanç, but then his family moved to another city and he moved with them. We’re talking about the high school days here. Our current bass player Hazar, was the vocalist then, and was also playing an electrified violin. He took up the bass later, so we had a period for a few years without a bass guitar after İnanç left. Also, in the very beginning there was a second guitar player, Alper. He also did some vocals and he also moved to another city with his family, and sometime later Gökçe took his place. This was around fourteen years ago.

Are any of you in any other active bands at this point or do you have any side projects going on? Have you released anything with any other bands in the past? If so, can you tell us a little bit about that?

Işık: We haven’t released anything with anyone else, nor are we in any other bands currently, though we sometimes casually play with other people. We do have some plans for side projects. Özüm started recording solo guitar stuff and I’m acting kind of like a producer, or facilitator for that, and the first fruits of that will be available here in a few months, I hope. I have some vocal songs that I wrote many years ago for Hayvanlar Alemi, which we for some reason couldn’t record, some my own simple compositions and some stuff where I write lyrics for melodies I take from traditional, usually Asian, songs. So, I want to record those with a little help from friends, either under my own name or under the band’s name if the other guys like the stuff. Özüm and I also want to have an experimental two-guitar project, where he’ll improvise on simple backgrounds and I’ll provide my extremely rudimentary guitar skills.

How old are you and where are you originally from?

Işık: We were all born in 1985 and grew up in Ankara, Turkey.

What was the local music scene like where you grew up? Were you very involved in that scene? Did you see a lot of shows growing up or anything? Did that scene play an important role in shaping your musical tastes or in the way that you all perform at this point?

Işık: Classic hard rock and heavy metal was the big thing in Ankara when we were growing up. That was the first stepping stone for many kids who started a musical career in those days. We saw ourselves as rockers/metalheads in our early teenage years, though because we were too young to be allowed into bars and all that, we didn’t see that many shows, even though there was a big scene. In the later teenage years, we were very interested in the new underground scene in Istanbul. There were quite a few bands, ZeN, Baba Zula, Replikas, Nekropsi and others, playing a music that was a mixture of experimental rock, Anatolian folk, Krautrock, psychedelia, electronics, etcetera. We saw them live whenever possible and that had a big impact on our musical development. But as that was happening in Istanbul, we were not a part of that scene. When we started playing in cafes and bars in Ankara in 2003, there wasn’t much of an experimental scene there to speak of. In the years that followed we came across only a handful of bands who we could somehow relate to and share a stage with.

What about your home when you were a kid? Were either of your parents or any of your close relatives musicians or extremely interested or involved in music?

Işık: My parents liked music, but weren’t extremely involved in it. There wasn’t a cassette or record player at home when I was very small. That changed when they bought a car, and I was exposed to music they and my brother were listening on the road. This would either be folk music or some other folk-based left wing political music, like the folk-rock of Cem Karaca, protest music, or some socialist ensembles from Turkey, kind of modeled on the Chilean band Inti Illimani. I also remember one evening there was a broadcast of a Joan Baez concert on TV and my parents recorded it to VHS. When I was fifteen my father took to me to North Korea to a children’s camp, via China, and there I had my first proper exposure to East Asian music. So, that’s my parents’ impact on my musical life. I started professionally consuming western popular music when someone gave my mom a CD as a present for the kids when she was on a visit to Germany, it was a Jive Bunny & the Mastermixers CD, with cheesy mixes of old rock’n’roll songs that sounded very impressive to me at that age. I was around eight or nine, I guess. Around that time, my brother, who’s six years older than me, bought Queen’s Greatest Hits on cassette, which lured me more into rock music.

Özüm: I also remember mostly listening to the music in my parents’ car on the road. They were into Turkish folk-pop and pop music of the early 90s. Some I loved, but some I hated, and still hate due to listening one tape over and over again during long car trips. Later on, before I met these guys, my older cousins had a huge impact on my musical taste and what I was exposed to. I had a Walkman in the fifth grade of elementary school and as far as I remember the first cassette I ever bought was Manowar’s Kings of Metal album because my cousin had just bought one and I had to get one too!

What do you consider your first real exposure to music to be?

Işık: Well, that would be hard to remember, no? Music is all around when your brain is developing as an infant, you get it from the radio, television, weddings, the national anthem, the call to prayer, etcetera. I guess my earliest experience that I can recollect where I was consciously attentive to music involves my aunt. My mother was working, so I would spend the morning at my grandparents’ place, where my aunt was also living. She would sometimes put me on her shoulders and sing me some songs as we walked around the house; children’s songs in Turkish and French. I think she also sang “Speedy Gonzales”. She called them “Shoulder Songs”. My grandparents would also sing sometimes when they were joyful, folk songs usually. Though my grandfather would also sing in French, a language he knew when he was young, but then forgot. He was also almost totally deaf, so there was a lot of shouting in the house to make ourselves heard to him. Maybe that’s how I became tolerant of very loud music. And we were living very close to the biggest mosque in Ankara, and there would often be funerals of important people and soldiers, and the army band would play Chopin’s Funeral March. I liked that a lot.

Özüm: I’m not sure… I guess if you skip the voices you hear during maternity and lullabies after that it has to be related to TRT, the national, and only, television channel in Turkey when I was a child. They used to show classical music concerts and old Western movies on Sundays.

If you were to pick a moment that seemed to change everything and opened your eyes up to the infinite possibilities that music presents, what would it be?

Işık: Discovering Frank Zappa. That was more like a process than a moment though. From age fifteen on, for a few years I was living daily with his music. That removed all the barriers for me. The second process was opening up to international music and coming across scales, sounds and structures I hadn’t imagined before. For instance I still remember listening to the Burmese “Princess Nicotine” compilation on Sublime Frequencies for the first time. That thing, for example, sounds like nothing else you would hear from the American or Turkish musical world. Or, I remember how I listened to Ethiopian 70s music for the first time and had to stay up the entire night to listen to it again and again.

Özüm: I don’t remember one band or person opening up my mind, but listening to an impossible variety of music enabled by illegal mp3 downloading had a huge impact. That was during the period where we, especially Işık, hoarded music from remote and weird times and places in the world, and that was also when we discovered Sublime Frequencies. And I have to say that this period of our lives wasn’t just about opening up our eyes to infinite possibilities that music presents, but to all aspects of life.

When did you decide to start writing and performing your own music and what brought that decision about you?

Işık: So, in the very beginning we only did covers, hard rock covers. But Hazar was also playing violin, so we wanted to find a song that had violin in it. This was shortly after I got into Zappa, and he had this song called “Willy the Pimp”, on the Hot Rats album, sung by Captain Beefheart, and Jean Luc-Ponty plays violin on it. So, I said, “Why don’t we do this one”? Our second guitar player at that time was a huge Megadeth fan and he was singing with this coarse Mustaine-like voice, so he took the role of Beefheart and did a good job. Anyway, this song had a very long guitar solo in it. As we weren’t able to play the solo as it is, we decided to improvise. That was the first time we deliberately improvised in the studio, but by the end of it we liked improvisation so much that we turned into a free-improv band. We just jammed and played almost nothing else. That was a quite long period, up until 2005. Our first CD-R, recorded in 2003, is fully improvised. Later, we started to add some pre-established structure to the improvs and started writing songs.

What was your first instrument? When and how did you get that?

Işık: All of our first instruments were recorders I think, that we had to play in the music classes in the primary school. I guess many of us also had toy keyboards. Those things aside, I took up the guitar in the secondary school, but I was too lazy to practice, so it didn’t go anywhere. Then I decided to be a drummer after we formed the band, and my mom bought me a drum kit when I was around fifteen. I guess, a bit before that I bought myself some traditional hand percussion, a darbuka and a bendir. It was quite common for rock kids of my generation to open up to traditional music and get their hands on these kinds of instruments.

Özüm: The first instrument I ever played wasn’t a recorder, but a digital keyboard that my father had in the house. I took some classes and I recall only hatred and boredom towards the instrument. I used to play with it at the house and listen to my father practice Concerto De Aranjuez’s Adagio section by Rodrigo. Later on, I started taking classical guitar lessons from my music teacher at school. So, my parents decided to buy me a classical guitar when I was twelve. That was my first real instrument and I still play it.

How and when did the members of Hayvanlar Alemi originally meet?

Işık: It was the first year of the secondary school in Ankara. We were twelve or thirteen years old, the teacher was the arbiter of who sits where in the classroom, and Özüm and I were told to sit together. We didn’t talk for a few days, then during one class Özüm turned to me and said, “Do you know how to make games”? ‘Making a game’ means drawing something on paper that resembles a computer platform game, one kid moving through the platforms with his pencil and the “maker” of the game telling what challenges and monsters the other one encounters. So, we became friends and soon we were exchanging cassettes. I was giving him Queen and he was giving me Pink Floyd. Hazar was in the same class and involved in the cassette exchange thing. We met Gökçe later in high school. He was more of a punk/metal guy compared to us, and at first I wasn’t very happy with the idea that he joined the band, because I didn’t want the band to go in a harder direction. But within a year Gökçe’s playing completely changed, sometimes even playing just keyboard-ish ambient/atmospheric lines.

What led to the formation of Hayvanlar Alemi and when would that have been? I read somewhere that you all started off as a cover-band of sorts and evolved to performing and recording your own material. Is there any truth to that, and if so, can you talk a little bit about that transition and what brought that about?

Işık: I think this question is answered in the questions above, but to summarize: Rocker-wannabe classmates form a band as young teenagers and do covers of Black Sabbath, Dream Theatre, Queen, Pink Floyd, and Rainbow, but then accidentally get into improvisation and turn into an all-improvisational psychedelic band, and move on from there to different horizons that will appear in the answers to various questions below.

Is there any sort of creed, code, ideal or mantra that the band shares or lives by?

Işık: Not really. Or maybe there is, implicitly, but we’ve never talked about this among ourselves. We’re just trying to create music based on our collective and individual experiences, without trying limit ourselves by anything that is external to us. However, the fact that we’re trying to consciously not put any ideal into the music doesn’t mean that it doesn’t embody an ideal. By which I mean, one can look at the music we’re making and draw some morals from it. We try to have as broad a range of influences as possible and try to reflect that fact in our music, without committing ourselves to a style, tradition, scene or market. There’s an ocean of music in the world to be inspired by, but most people, even when they’re very open minded about many elements of music, still geographically feed on a diet of their local music plus whatever comes from where we can roughly call “the West”. The dependence on the West is so huge that even when people go beyond western music or their local music, let’s say when they discover Tuvan throat singing or something, that discovery depends on western musicologists or labels documenting that stuff. But no, you don’t have to necessarily depend on that. You can pick a random country, say Kazakhstan, and find a radio station on the internet and listen to what’s getting played there. If you happen to travel to Portugal you can pick up local recordings or go and hear what people play there. If you come across the archives of the state TV of Paraguay on YouTube you can dive into it and search for treasures. Music would be so much more colorful if everyone were explorers. And it doesn’t require professionalism, but unfortunately most bands stick to a very limited diet of scales and structures. I don’t mean this in any negative way, it’s just something that should be given some reasonable consideration.

Who came up with the name Hayvanlar Alemi and how did you all go about choosing it? I know roughly translated from Turkish it means Animals Livestock. What does it mean in the context of your band name? Are there any close seconds you can remember you almost went with?

Işık: It doesn’t mean Animals Livestock. It means The World of Animals, literally, or Animal Kingdom if we translate it in biological terms. We were first called Stargazer, for a short while, after the song by the hard rock band Rainbow. “Stargazer” was also a song we used to play, actually we played it on our first show in high school along with Black Sabbath’s “Computer God”, but by then we were called Hayvanlar Alemi already. I think we took up Stargazer as a temporary name and we were looking for a new one, and during classes I would think of names, and during the breaks I would tell them to the others and they would reject everything I would come up with. Then one day, I said, “Let’s make it something like Hayvanlar Alemi” and for some reason everyone immediately agreed. With that kind of teenage mentality I was looking for a name that sounded odd or offensive, to express that we’re, you know, a different kind of band. ‘Hayvan’ (Animal) is an insult word in Turkish, referring to a rude person usually. So, that’s how it was supposed to be an aggressive name. I guess it worked, as once one of our teachers in school didn’t approve of our concert posters because of the name. So, anyway, it doesn’t mean much in the context of our band, it’s just a name we’re stuck with. It has its beauty in a way, and a lot of connotations, but at the end of the day, it’s a silly name and makes it hard for people to find us on search engines.

Where’s the band located at this point?

Işık: Özüm moved to İstanbul from Ankara around a year ago. Hazar has been living in Stockholm for years, with a year or two in Greece sandwiched in between. Gökçe has been living in the East Coast of the US for a long time now, first Connecticut, then Long Island, and now he’s moved to Washington D.C. I’ve been living in Budapest for a few years and then spent a few months in Boston. Very soon I’m moving to Switzerland for a year and then back to Budapest. So, we’re not really based anywhere. All this mobility is due to studies and work.

How would you describe the local music scene where you’re at?

Işık: In Ankara there’s almost nothing interesting going on as far as my taste are concerned. There’re tons of bar bands doing covers, some of them good though, and a lot of melancholic mainstream rock bands. Then, there are various urban incarnations of folk music, and a growing club scene. It’s sort of similar to Istanbul in certain ways, but Istanbul has a much more lucrative music scene including tons of experimental and underground musicians. However, the particular brand of experimentalism we’re interested in has been vanishing and giving way to other things in recent years. Most young people nowadays play singer-songwriter kind of stuff, or indie rock sounding things, and seem to be totally uninterested in the folk-psych-avant-rock thing that our generation was interested in. There are some pretty good DJs in Istanbul, though.

Do you feel very involved in the local scene at all? Do you book or attend a lot of shows or anything?

Işık: In the past, when we all used to live in Ankara, we felt like we were really involved in the local scene. It was a very small experimental rock scene and our band was one of the building blocks. More often than not we were invited to play in Istanbul, but we still weren’t able to make our name heard in Istanbul outside of a circle of musicians and a group of other people, and without that it’s not really possible to make yourself known on the national level. Then, a bunch of us moved abroad and lost touch with the everyday music business here in Turkey. Almost all of the bands in Ankara we used to play with broke up, the places which used to invite us to play in Istanbul closed down, and the new generation wasn’t very interested in the kind of stuff we and some of our contemporaries were doing. So, over the past few years we’ve been playing in Turkey maybe twice a year, and the number of people attending the shows keeps getting smaller and smaller. I hear similar things from other bands that represent the late 90s and early 2000s musical scene around here as well.

Has the local scene played an integral role in the sound, formation or history of Hayvanlar Alemi, or do you all feel like you all would be doing what you’re doing and sound like you do regardless of where you were at or what you were surrounded by?

Işık: I guess the predominance of rock and metal in Ankara was essential to our formation and its effects continue in our music, albeit in a somewhat transformed way. But other than that, no, as we said above, the experimental rock scene was very dull in Ankara and most of our musical influences came from what we discovered on the shelves of music stores and on the internet. Maybe being surrounded by this dull musical environment made us more eager to look elsewhere for inspiration, and Ankara’s feel as a grey administrative city and its harsh winters may have had some effect on our interest in exotic places and musics in an escapist or utopist fashion. Looking at our very early work, I can hear the depressive effect of Ankara on the music, and then an escape from that in later works by adding more exotic influences. However, if by the local music scene you mean Turkey in general and not Ankara specifically though it’s easier to say that we wouldn’t sound the same if we weren’t from Turkey. Local Turkish traditional music is one of our big influences, and we were influenced by a lot of Istanbul bands which we probably wouldn’t know about if we weren’t from here.

Are you involved in recording or releasing any music at all? If so, can you tell us about that briefly here?

Işık: We self-released all of our early CD-Rs, but I’m talking about unofficial releases here. We haven’t recorded or released anyone else’s music, which is what I’m guessing you’re asking about. Here in a few months I am hoping to establish a digital label though, to release our own stuff at first, and then some obscure and forgotten stuff from Turkey as well as a few other things. I’m planning on calling it Inverted Spectrum Records.

Whenever I so these interviews I always end up having to describe how a band sounds to a bunch of people that have never heard them before. On top of that, I have to do it for bands that I like! It’s become a kind of neurosis for me, seriously. It keeps me up late at night sometimes worrying that I’ve put too much of my own perceptions and thoughts about something in there. Rather than feeding to the growing ulcer in my stomach how would you describe Hayvanlar Alemi’s sound to our readers who might not have heard you all before?

Işık: That’s not a very easy thing to do. We’ve sounded very different during different periods. Some of it has had more improvisation in it, some of it was more DIY or lo-fi, some of it sounded like post-rock, some had a dub-reggae skeleton, and a bunch of songs even had vocals. If you want an overall description, imagine an instrumental brand of guitar-heavy neo-psychedelia, with some influences of surf and a few other things flavored with scales, melodies and rhythms from all over, The Middle East, Bolivia, Peru, Thailand, India, Russia, Cambodia, Indonesia, Spain, Ethiopia, Mali… Some people find some of our stuff similar to a certain period of the Sun City Girls, particularly their Torch of the Mystics era, and I think we do have things in common. We discovered Sun City Girls when a music journalist, Jay Dobis, told us that we should check them out because there were a lot of parallels between our stuff. That was in early 2005, when we had only released one thing, our first CD-R Bir. For a description of our more recent sound see question thirty-one.

While we’re talking so much about the history and sound of the band I’m really curious who you all would cite as your major musical influences? What about influences on the band as a whole rather than just individually?

Işık: Talking about the band as a whole, when we were teenagers we were all heavily influenced by classic rock and some metal, as well as some progressive and psychedelic rock, like Pink Floyd, King Crimson and Yes. We were also listening to some 90s music, both alternative and pop, as well as some post-rock, trip-hop, and stuff like that. At least Özüm and I, if not the others, were pretty moved by Zappa and Beefheart. Then came a period where we were under the influence of an experimental-psychedelic scene happening in Istanbul, we listened to bands like ZeN, Baba Zula, Replikas, Nekropsi, Fairuz Derin Bulut and Saska. That period also heightened our interest in local folk music and other folk-inspired music, like the band Moğollar who’s been around forever. The scope of this interest then spread to local musical styles from around the world, especially the parts of the world mentioned in the previous question. Some of us also got into Can and Velvet Underground, and around that time I spent a year in Russia and picked up some stuff from there and the other guys in the band liked some of what I brought back. There was some alternative Russian rock from the early 2000s, but there was also some more classic and ethnic music, both Russian and from other peoples of the federation, that was when I discovered Tuvan throat singing. Surf music’s another thing that had a big impact on us, I think we particularly liked The Astronauts, and then there’s this horror-surf band called Deadbolt. Yawning Man and the first album from The Swords of Fatima were big influences as well, even though they’re not a hundred percent surf. And there was one period where we were heavily under the influence of dub-reggae; Scientist, Horace Andy, African Head Charge, etc… American Primitivism, like the music of Robbie Basho and John Fahey should also be mentioned. At some point we were digging into a lot drone music, New Weird America bands, and Gang Gang Dance. More recently we’ve gotten into some stoner rock kind of stuff. We’ve also been listening to some bands which share our interest in taking global sounds seriously, Sun City Girls and their side projects, Neung Phak, and Dengue Fever all of which I count as influences. Besides what I mentioned above, as for more personal stuff, I can count Swans, Earth, and Grinderman as more recent influences. I’ve been a fan of the Russian bands Auktsion, Leningrad and Kino, and songwriters like Jonathan Richman, Lee Hazelwood, Tom Waits, Sixto Rodriguez, Serge Gainsbourg, Marc Almond and Chinawoman too, though, I don’t how much these influences are reflected in our music. I’ve been into a lot of 60s and 70s cinematic library music recently, particularly the Italians like Bruno Nicolai, 60s French ye-ye, 70’s rock from old the Soviet states, South American Cumbia, Indian and Pakistani pop and traditional music, Cambodian rock, and Mulatu Astatke. I had an intense rockabilly-psychobilly period a few years ago and got heavily into The Cramps, but that’s mostly over now. There are way too many things to mention here, but they all feel essential to me. It should be said however that a lot of our influences are probably sort of anonymous. I mean, the sound not only comes from the bands and musicians you love, but things you hear here and there and maybe don’t even remember the name of the artist; some obscure track on a surf compilation, something from an Indonesian field recording, a one-shot UK 60’s psych band that found its way onto YouTube years after its release, something you hear from a truck passing by, an electronic beat you pick up in club, a song which was popular when you were four years old, etcetera.

What’s the songwriting process like for Hayvanlar Alemi? Is there someone who usually comes in to the rest of the band with a riff or more finished idea for a song to work out with the rest of you collectively as a band? Or, do you all just get together and kind of kick ideas back and forth and jam stuff out until you’ve worked out something you’re interested in refining?

Işık: It’s very rare, though not non-existent, that someone comes in to the band with a riff or a pre-written song, but this might change in the future as we’re physically separated most of the time and can’t easily write songs in the collective method we used to. If someone comes in with something it’s more of an idea, or a particular way to play a song. We usually just get together and play and something comes up, and we say “Hey let’s play this again.” This can happen during concerts too, for example “Geneva Incident” and “Perils of Haarlem” from the latest album were born from concert improvisations. Sometimes we discover some improv we recorded a long time ago in our vaults and decide to work on it and sometimes we just jam, record it and then release it, though there or no tracks like this on the last two albums. Sometimes an improv section of a song played in concerts turns into a song of its’ own over time. “Horsepaper” from our most recent album and “Welcome to Sunny Australia” from the previous one both used to be improvisational extensions to the song “Mega Lambada”.

What about recording? I’m a musician myself and I think that most of us can appreciate the end result of all the time and effort that goes into making an album once you’re holding that finished product in your hands. But getting to that point, getting stuff recorded and sounding the way that you want it to especially as a band, can be extremely hard on a band to say the least. What’s it like recording for Hayvanlar Alemi?

Işık: Yeah, sometimes I wish I was a poet or something, so that there would be very a short distance between what’s in my head and the final product. On record we rarely sound the way we want to partly because of our geographical separation and also partly due to financial reasons. We can spend very little time in the studio, so it’s like we have two hours to record a song, and we mix and master it for months getting it to sound approximately like we want it to, and it’s still never perfect.

Do you all like to take a more DIY approach to recording where you handle stuff mostly on your own so that you don’t have to work with anyone else or compromise on the sound with a second party? Or do you all like to head into the studio and let someone else handle the technical aspects of things so that you can just kind of concentrate on the music and getting the best performances possible out of yourselves?

Işık: We recorded some of our very early stuff with a portable recording device. Otherwise, our stuff was recorded by whoever was available in the studios we rented. Hazar and Özüm are the most technical guys in the band and they wanted us to have our own studio at one point, but it never happened.

Özüm: Well, except for a guy who records the session, we don’t work with anybody else. Unfortunately, this isn’t by choice, it’s just that we’ve never had the money for mixing, mastering and all that other production stuff. Hazar and I are a bit geeky about instruments and music production, and over the years we’ve had to learn by trial and error. Still, I think we’re making barely-decent mixes. I couldn’t even think about leaving the sound and mix completely to someone else at this point, but I would love to do it with a sound engineer who knows what they’re doing. For the time being though, I’m content with recording in a studio which has a good recording equipment and acoustics.

Is there a lot of time that goes into getting a song to sound just the way that you want it to before you go in to record? Where you have ever single part of a song figured out and planned din advance? Or, do you get a good skeletal idea of what a song’s going to sound like and allow for a little bit of breathing room, evolution and change during the recording process?

Işık: It’s only rarely that our songs are written from beginning to end. There’s usually breathing room, sometimes a little bit, sometimes more; and occasionally there’s nothing else other than the breathing room, its formless oxygen all around. For most songs, we have skeletal ideas and play it over and over during shows and rehearsals and things start to fall into place, and the song is still taking shape when we press the record button, and continues to evolve well after that. Compare for example, “Med Cezir 2013” from our latest album and the version on Demolar 2008-2009 which we recorded years ago.

Özüm: Usually the songs we record are ones that we’ve already played and/or improvised during concerts or rehearsals. For those songs we certainly have a sound in our minds, mostly influenced by the way we sound on stage. This is quite unfortunate, because you never play the same way or sound the same in the recording studio. Unlike breathing room, it’s a suffocating box, everything works against the sound you have in your mind. There’s just not enough time, you’re paying by the hour, and usually, you don’t really enjoy the experience.

Do psychoactive or hallucinogenic drugs play a large role in the songwriting, recording or performance processes for Hayvanlar Alemi? People have been tapping into the altered mind states that mind altering substances produce for thousands of years and I’m always curious about it.

Işık: Without being too explicit about the answer to this socially and legally sensitive question, let’s say this: When we’re recording we’re almost always sober, and on stage occasionally tipsy or drunk. I think most artists today who are inspired by hallucinogens don’t record when they’re actually tripping; the hallucinogenic experience is something that they internalize and then finds expression in their work. Our first experience with hallucinogens was in the summer of 2004 when four of us travelled to Amsterdam back when magic mushrooms were still legal there. I see that as a very meaningful and inspiring collective experience for the band, something that defines the common memory and ‘folklore’ of the band reflected in the work that came after it. I should also note here that I think alcohol’s a very underrated substance in terms of the “altered mind” discourse. It’s so common and mundane that we don’t give it as much artistic significance as other substances these days and merely see it as entertainment material, even though a mundane alcohol-induced high can be very spiritual and inspiring if you want to look at it that way.

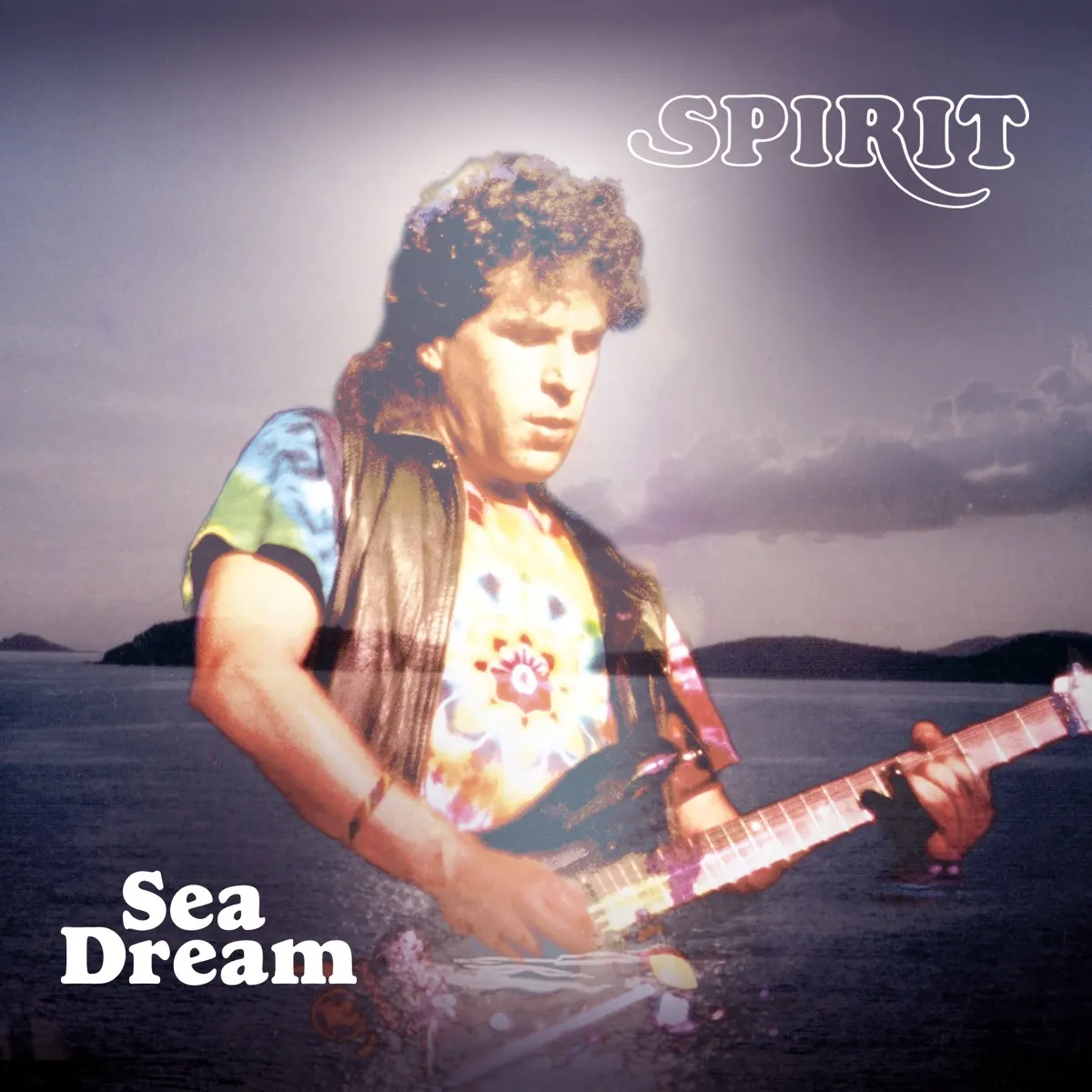

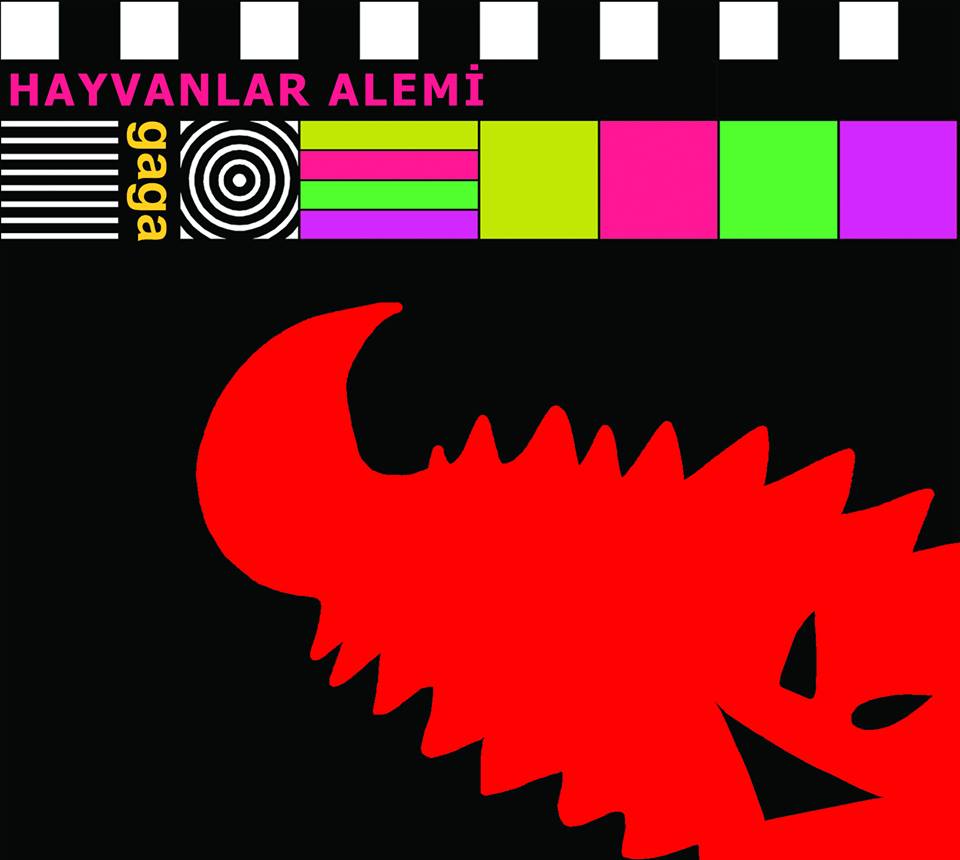

Let’s talk a little bit about your back catalog. In 2007 you all released the Gaga CD for 003 Records. What was the recording of the material for Gaga like? Was that a fun, pleasurable experience for you all? When and where was that material located? What kind of equipment was used? Who recorded it?

Işık: That’s a very long and complicated story. Recording that album was a process full of misfortune, so much so, that after it was all over we thought for a long time we would never try to release an official album ever again (But then things changed, see question number twenty-eight). Gaga was recorded in Ankara at the studio of a guy who was the husband of a girl who was working in the office of Özüm’s parents. The guy was a death metal vocalist/guitarist, but open-minded about other styles. He had a new record label, and had been following us for some time to offer us a record deal, waiting to see that our music was ready. And so one day there came a point when he offered us a deal after a show. Our music wasn’t really mature enough, but Hazar and Gökçe were going abroad to study in a few months and we thought we might not ever have the chance to record together again. We were also younger and ultra-excited. So, we wrote a couple of loose compositions based on our on-stage improvisations, and there were a couple of cover songs, one Indonesian and one Nepalese, a spoken word thing, a couple of songs with vocals… We recorded those, had a couple of improv sessions in the studio, and then pulled a few songs from those sessions. To this day, it’s the only time in our career when a studio was allocated to us for a few days. We recorded for four or five days, but then there was a fire in the studio and it was unusable for a few weeks, but when it was available again we finished up the recording in a couple more days. After it was all done, it turned out that there was problem with the guitar recordings that lowered their sound quality, but it was too late. The release of the album was delayed because of the fire and the complicated mixing process due to the problem with the guitar recording, and we had to play the already booked album launch concert without there being an album, despite the fact we had paid some of the expenses for the album to get it released earlier. On the concert night, we had some problems with the record label people. Apparently we didn’t play well, partly due to some of us drinking too much. Also, I borrowed some cymbals from one of the guys from the label, and we had two dancer girls, and at some point one of the girls was hitting one of the borrowed cymbals with a knife which could potentially damage the cymbal, and the owner of the cymbal got extremely pissed off about this. The next day they told us that they had decided not to release the album. This pissed us off really bad as we were very young and excited people. The summer of 2006 was a very stressful summer. I also had some other personal problems on top of all that, and I remember I was drinking day and night. Anyway, we told them that we wanted to release the album unofficially on the Internet and wanted the money we contributed back, but then for some reason they decided to release it again, so it was released basically without a label who wanted to seriously promote it. We sold around 370 copies out of 1000 and to this day we can’t find out what happened to the rest.

You released two CDR albums titled Demolar, the first Demolar 2007-2008 in 2008 and then Demolar 2008-2009 in 2009. Can you talk a little bit about the recording of the material for the Demolar collections? Who recorded that? Where was that at and what kind of equipment was used? Were those demo collections as the title would imply or were they part of actual recording sessions but weren’t previously used for one reason or another?

Işık: They were songs recorded with the intention of being unofficially released on CD-Rs and on the internet. They were first released as six separate CD-Rs and then compiled into these two collections. After the stressful experience with Gaga, we decided not to try to release an official album again and just did these unofficial recordings. It was a period when Hazar and Gökçe were abroad most of the time and Özüm and I were living very close, so it was very easy for the two of us to get together and create a lot of material in his room or my basement, and then just rent this relatively cheap studio for a few hours and record it. Most of the songs were recorded in a studio called ‘Raven’ in Ankara, again run by a metalhead, except for a few which were recorded on-stage and elsewhere. The metalhead sound engineer has since gotten out of the recording business and is running a meyhane (pub-restaurant) just opposite where his studio used to be.

Then, in 2010 you all released the Guarana Superpower 12” for Sublime Frequencies. Was the recording of the material very different than the previous sessions for Gaga and the Demolar albums? When and where was the material for Guarana Superpower recorded? Who recorded it? What kind of equipment was used? I know that 12” was supposed to be a limited edition but I couldn’t track down any numbers. Do you know how many copies the Guarana Superpower 12” was limited to?

Işık: I think it was 750 or 1000 copies, and then there was the CD version too. The recording session wasn’t different at all. Indeed, most of the material comes from the Demolar collections, except for three songs which we recorded exclusively for the album. It’s a compilation. When we recorded Gaga we approached Alan Bishop over the internet and asked if he would be interested in releasing it on his Abduction label. He declined, saying that the label wasn’t active anymore, but he kept following our music on the internet as we released the aforementioned demos, and then approached us with the idea of doing a compilation. He had some other label ideas in the beginning, but the album finally ended up on his Sublime Frequencies.

You also self-released the Visions Of A Psychedelic Ankara CDR in 2010. Can you tell us about Visions Of A Psychedelic Ankara. When and where was the Ankara material recorded? Who recorded it?

Işık: We were listening to a lot of dub and reggae during the days leading up to this album. We even ended up playing in a reggae festival at some point; we were invited for some reason, maybe because we had some reggae rhythms on a bunch of songs on the previous demos. Anyway, we had this fantasy of creating a dub record, but in our own psych-rock fashion which led to Visions of a Psychedelic Ankara. The title is a reference to the African Head Charge album Vision of a Psychedelic Africa. It was recorded in the same place. During this process, the metalhead guy who ran the studio confessed to us, in an emotional moment, that his favorite music was actually reggae. This was only four years ago, but the music we were playing then seems so far away now. Anyway, the album is going to be re-issued on vinyl in the not-so-distant future with bonus tracks. Follow us for details.

In 2012 Sublime Frequencies Records released the Yekermo Sew 7” from you all which had two new songs from you all. Were those songs written or recorded specifically for that single or had they been around for a while looking for a place to call home? If they were recorded specifically for that single can you tell us a little a bit about that?

Işık: Yeah, the idea was to do a single, I’m not sure how we came to that point though. We had this song, but I guess not enough others to fill up an album or EP. At that stage I had already moved abroad and we weren’t really able to meet with Özüm often to create new material. Plus, we were going to go on tour and needed something new to support the tour. I guess that’s the primary reason we did the single, but it also sounded like an interesting idea to have a 7-inch single in our catalog. You know, to show the grandchildren. It was recorded in Istanbul in a studio called Deneyevi. The track on the b-side comes from an improv session in Ankara; it’s filler.

Earlier this year you released the Twisted Souvenirs album for Unrock Records. Did you try anything radically new or different when it came to the songwriting or recording process of Twisted Souvenirs? What can our readers expect from the new album? When and where was it recorded? Who recorded it? What kind of equipment was used?

Işık: I wouldn’t say we tried anything radically new, but the album still ended up sounding different than our previous stuff I think. I guess we just happened to write harder, darker songs. We say it’s more ‘rock’ compared to our previous records, it reflects better how we sounded on-stage in the past four years or so. Actually, maybe it’s harder because it mostly evolved on-stage rather than at home or in the studio, as we tend to play heavier on stage. People who have heard our stuff on-stage recently have been giving it names like heavy psychedelia, light stoner or oriental stoner. A reviewer from the Wire compared the aggressiveness of the music to Kyuss, I’m not sure how good that comparison is but it should give an idea. The international influences are still there; there’s a dark surf piece in flamenco scales, some vague far eastern motifs on a song, which someone once suggested be filed under “surfcore”, a loud psych cover of a Turkish pop song, and a heavy funk cover of Mulatu Astatke’s “Yekermo Sew” is also included. I feel like the international influences are somewhat less pronounced, compared to the Guarana Superpower album where almost every track made a reference to some global style though. The occasional cheerful or comical side of Hayvanlar Alemi, both in the music itself and in presentation, is also largely absent from this record. It feels like a more serious record to me. People also say it’s more mature. When it comes to the recording, most of the material was recorded on the road two years ago as we didn’t have any other time to meet each other. Some were recorded in Stockholm after we met Hazar there to play in a festival in Estonia, some were recorded in Amsterdam, as early as nine in the morning, when we had a day off on a European tour, and a couple of tracks come from 2011, recorded in Ankara and Istanbul.

Özüm: I should add that this recording spree was full of quality recording studios. At least for me, it was the first time I got to record with some boutique amps and effects that were present in the studios. However, due to a lack of time there are no interesting experimentations with recording and sound.

With the release of Twisted Souvenirs not super long ago, are there any other releases in the works or on the horizon at this point from Hayvanlar Alemi?

Işık: There are the side projects I mentioned before; I hope some of them will materialize in the next few months at the most. We do have some material for a new album or an EP at least, songs that we’ve been playing for a couple of years but didn’t end up on this new album because they weren’t mature enough and because they have a comparatively lighter mood. So we have to get together at some point to polish that stuff and record it. There are some recordings from improv sessions that we’ve wanted to release for a few years now, I think in the following year they’ll finally be released as the fourth installment in our unofficially Hayvanthropological Field Recordings series. Our first demo, Bir from 2004, is coming out on cassette, limited to a hundred copies too, and there’s also the vinyl re-issue of Visions of a Psychedelic Ankara I mentioned before.

Where’s the best place for our US readers to pick up copies of your stuff? With the insane international postage rate increases over the last few years I try and provide our readers with as many possible options for picking up imports as I can!

Işık: Forced Exposure is the distributor for the US, so it can be ordered from there, or I guess people can find out via Forced Exposure which stores our records end up in. I saw our previous stuff in Criminal Records in Atlanta and Weirdo Records in Cambridge Massachusetts, so I guess they might end up there or Permanent Records in Chicago, where you heard the new one. For other states or cities, I don’t know.

What about our international and overseas readers?

Işık: Norman Records is the distributor in the UK, and international readers can easily order it from the German label, Unrock.

And where’s the best place for our interested readers to keep up with the latest news like upcoming shows and album releases from Hayvanlar Alemi at?

Işık: Our website and our Facebook page.

Are there any major goals or plans that Hayvanlar Alemi’s looking to accomplish in the rest of 2014 or 2015?

Işık: Well yeah there are the release and recording projects we mentioned above. Because we have been living in different countries for the past years our productivity suffered quite a bit and for the rest of 2014 and 2015 we want to change that, we want to try to get together more often and do a lot of stuff. We also want to collaborate with a musician who we like a lot and who we had the chance to befriend, but we haven’t approached him about this yet so let’s keep the name as a secret for now. Also Özüm and Hazar is establishing a pedal company, which they can tell you about.

Özüm: Yes, we’re planning on getting into the effects business, like there are not enough manufacturers already! But Hazar and I have been brewing ideas, exchanging sketches and building prototypes for almost a year now. Hopefully we’ll release one of them will before 2015. Those who are interested can follow us out at www.facebook.com/soundbrut.

What, if anything, do you all have planned as far as touring goes for the rest of the year?

Işık: In 2015 we hope to tour more, maybe do something after the Visions of a Psychedelic Africa re-issue. We also want to tour Eastern Europe, possibly collaborating with the very interesting Serbian band BICIKL.

Do you spend a lot of time out on the road? Do you enjoy touring? What’s life like on the road for Hayvanlar Alemi?

Işık: We play maybe two shows in Turkey each year, which used to be more in the past when we were all living there. We have a short tour in Europe once a year usually, and sometimes have one-off shows at festivals, so we don’t spend that much time on the road as all of us have other jobs or studies. It’s usually enjoyable when it happens, but it depends a lot on the venue and the audience. We usually get along with each other on the road even though we have different expectations when it comes to the side-adventures of touring and occasionally get on each other’s nerves. I think we’ve only had a fight once. We had to stay one night on the road on a free day, and we ended up in a slightly more expensive hotel due to my insistence on going to Frankfurt rather than some small town, and Hazar burst at me in anger and I burst back, but we were drinking together again in forty-five minutes. Touring is a dizzying experience overall, one night you play in a state-sponsored concert hall and another night in a smoky barely-legal club, you sleep in a proper hotel one night and on a couch in a squat on the other, and the language and currency changes all the time.

Do you remember what the first original song that Hayvanlar Alemi ever played live was? When and where would that have been at?

Işık: It was in high school, at a new year’s party in December 2001 I guess. We were very noisy and chaotic, everybody ran away. We were just playing improvisational music at that time, so I’m not sure if we played any “songs” per se, but I remember our bass player playing some motifs he had came up with in the studio before. We probably played “Yerçekimsiz Ortam” based on one of his bass-lines, if we didn’t play it on at concert we definitely played it at some other concerts in the high school. Indeed, for a very long time that was the only “song” we played along with the jamming, all the way up to 2005. We still play that one, when we run out of songs during an encore and there’s nothing else we’re well prepared, we just pull that one out.

Who are some of your personal favorite bands that you’ve had a chance to play with over the past few years?

Işık: We had the chance to play with Sir Richard Bishop a couple of times, and also at the same festival with The Brothers Unconnected, All Tomorrow’s Parties, we had the honor of going to the festival in their tour van. We even had the chance to play with Replikas, a Turkish experimental rock band which we like from way back. It also happens sometimes that we’re coincidentally matched on a show with a band we don’t know and they turn out to be quite impressive. A Canadian band called Basketball and Chicha Libre are two such names I can recall right now.

In your dreams, who are you on tour with?

Işık: An all-female international acid folk orchestra from 1967 called “The Open Gates”.

Do you have any funny or interesting stories from live shows or performances that you’d like to share here with our readers?

Işık: Can’t think of anything right now, except for an occasion where we played in a reggae festival called “Unite In Paradise” in a seaside location in Turkey. The festival was just a total failure. The company that rented-out the sound system came in the middle of the day to take back the equipment, but after hours of negotiations, with our bass player Hazar playing a main role, the festival continued, and instead of playing at four in the afternoon we played at midnight to a stoned and drunk reggae crowd who had been waiting for live music since morning. Our shows used to be more eventful and funny in the past. We used to dress up in colorful ways, bring a lot of cheap decoration and items on the stage, tell stories, make the audience eat and drink stuff, play games with them, etcetera. At one point one of our “assistants” would go into the audience and force them to smell melons. Funny or interesting things would happen more at those kinds of interactive shows. We don’t do those things anymore though.

Do you give a lot of thought to the visual aspects that represent the band, stuff like flyers, posters, shirt designs, covers and that kind of thing? Is there any kind of meaning or message that you’re trying to convey with your artwork? Do you have anyone that you usually turn to in your times of need when it comes to that kind of thing? If so, who is that and how did you originally get hooked up with them?

Işık: We cared about that a bit more in the past. In order to give a weird and confusing psychedelic feel to what we are doing we would dress up in bizarre ways on the stage. We had a lot of things printed out on cardboard, some on-stage and some which our “assistants” would parade among the crowd and show to the audience, with flyers, images and stickers put on tables, etcetera. We don’t do that these days. We focus more on the music. For visual stuff like covers we look for something that would complement the music, like most bands do I think. I don’t know if we’ve been trying to convey a certain message, but it probably reflects something nevertheless. If you look at our discography you’ll see that the covers have changed over time. In the very beginning you have this black-and-white, somewhat depressed cover, and then suddenly it becomes colorful in an exaggerated way, with a psyched-out cheap exotic, sometimes even comical feel, with ironic album titles like Summer Hits 2007, BEST BALLADS and Visions of a Psychedelic Ankara, then for the Yekermo Sew single and Twisted Souvenirs it starts to become darker and more serious again. For a long time we designed our own covers, but for Yekermo Sew we turned to someone else for the first time, an illustrator and colorist called Marissa Louise, from Portland. A few years ago she sent us an alternative cover she designed for one of our CD-Rs. So sometime later when we needed a cover for Yekermo Sew we checked her website again, liked her paper-cut art and ended up using one for the cover. For Twisted Souvenirs we also wanted to take a chance having someone else do it, both because we were busy and because we wanted to see what kind of imagery other people associate with our music. Michael from the Unrock label handed the duties to German photographer Philip Lethen and the results were very pleasing.

With all of the various methods of release that are available to musicians today I’m always curious why they choose and prefer the various methods that they do. Do you have a preferred medium of release for your own music? What about when you’re listening to or purchasing music? If you do have a preference, can you talk a little bit about what and why that is?

Işık: My preferred format to release our music is whatever format’s available at any given time that would allow the music to reach more people who would be interested in it. Nowadays it seems to be the vinyl and digital formats. As for what I prefer to listen to, vinyl has a nice sound but I don’t have a record player. Cassettes are becoming popular again in some circles, but I don’t like the sound. I’ve never been much nostalgic about them. Every time I bought a cassette as a kid I wished I had a bit more pocket money so that I could buy the CD version. As a person who doesn’t want to own a lot of material possessions and who moves a lot, my preferred format for listening to music is digitally.

Özüm: I love the way vinyl artwork looks and for that reason only it would have been my first choice for a release. However, I totally agree with Işık, if it isn’t accessible to people, the medium is useless. The digital format is great to spread your music and I’m totally okay with the sound quality you can get from it. Listening to vinyl is a fairly new experience for me, let alone releasing music on it, and frankly I have mixed feelings about it. I can’t really say that I prefer to exclusively hear music on vinyl. Recently, I somehow inherited a 90’s style Stereo Deck from a friend that’s the size of a small fridge. It has a record player too. But vinyl is hardly the reason why I enjoy the sound. If you can hear the music via a nice stereo system or quality headphones it doesn’t matter much whether the source is 192kbps mp3 or vinyl. I mean, surely it matters somehow, but you get my point! I listen to music mostly when I commute or do work on my computer, so my choice for listening is definitely the digital format.

Do you have a music collection at all? If so, can you tell us just a bit about it?

Işık: Currently my music collection consists of countless mp3s. I stopped buying CDs a long time ago, except for at concerts to directly support the bands and as a souvenir, and new albums by a few select bands that are very dear to me. What remains from the CD and cassette collection I have, which almost completely stopped growing around ten years ago, is mostly classic and progressive rock that I used to listen to a lot as a teenager; near-full discographies of Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart, Tom Waits, King Crimson, Iron Maiden and Queen and milestones of recent Turkish experimental music.

I grew up around my dad’s enormous collection of killer psych and blues music, plus just about anything else under the sun that rocks pre-1980. More importantly than that though, he would take me out and let me pick up random stuff from the local music stores that I was interested in. I would rush home, kick back with a set of headphones, read the liner notes, stare at the cover art and let the music carry me off on this whole other trip. Having something to physically hold and experience along with the musical always made for a much more complete listening experience for me. Do you have any such connection with physically released music?

Işık: Of course, like everyone else I suppose. They’re also good material to personalize your room and give it a feel or aesthetic, but I’ve been losing my habit of physically connecting to the music, for a host of reasons; see my answer to the question above. And who knows, maybe the album covers and booklets are restraining our imagination which would flow alongside the music. Nowadays, as I listen to most stuff digitally, sometimes I’m not aware of the cover for a long time, and when I find out what the cover’s like, sometimes I get disappointed, a bit temporarily alienated from the album. I feel as if what I was getting from the songs wasn’t what the artist is trying to give me. And speaking of physical connections, what about the album covers and visuals online? Sometimes I find myself just staring at the still image on a YouTube upload while listening to a song. Maybe that’s an online analogue of the physical connection you were talking about. And what about the music folders on the computer? I take care of them just as neatly as I used to with my tangible collection.

Like it or not, digital music is here in a big way. In my opinion though, that’s just the tip of the iceberg. When you combine digital music with the internet, that’s when you really have something revolutionary on your hands. Together, they’ve exposed people to the literal world of music that they’re surrounded by and allowed for an unparalleled level of communication while eradicating geographic boundaries that would have crippled bands in years past. On the other hand though, people’s interaction and relationship with music are constantly changing and I don’t think that the internet or digital music have done anyone any favors in that regards. While people maybe exposed to more music than ever, they’re not necessarily interested in paying for it and illegal downloading has become a way of life for a lot of people as far as their consumption of music. As an artist during the reign of the digital era, what’s your opinion on digital music and distribution?

Işık: With so much music to listen to and pay for, I can’t blame anyone for illegally downloading our music. A lot of people would be deprived of a lot of music that would change their life if they had to pay for it. Unless you’re a super famous band, you can’t make a living off selling albums anyway. What we earn from two concerts, or even one well-paying concert, can be equal to what we earn from selling a thousand-copy limited album through a label. For the US musicians reading this, I should note that you get paid a bit better for shows in Europe than compared to the US, so it doesn’t make a big financial difference for bands of our scale whether people buy the records or illegally download them. If more people hear it there will be more people coming to your shows and buying stuff from the merch table anyways, so I’m fine with people illegally downloading music and then clearing their conscience by supporting bands in other ways. What’s way more important is spreading the music and making sure it reaches the people who’ll enjoy it. The only reason I would opt for releasing a record on a label is that it helps the record get promoted and heard, and it helps keep things rolling in the long run in certain ways. For any album there will always be five hundred or a thousand vinyl enthusiasts and archivists who will make sure the record sells out and the record label survives, and the rest of the people can download it illegally. There’s also this psychological effect though, where if something costs some money, rather than being free, it feels like a more serious and valuable thing, and in that way sometimes paying for something can make people enjoy it more, but it doesn’t feel right to play such psychological tricks on one’s audience.

I try to keep up with as many good bands as I possibly can and listen to as much as I can, but I swear there’s just not enough time in the day to keep up with a percentage of the amazing stuff out there right now. Is there anyone from your local scene or area that I should be listening to I might not have heard of before?

Işık: Well that would be a lengthy list, so we should narrow it down to what I take to be your main interest, contemporary psychedelic rock. As far as bands from Turkey are concerned you should check out, Replikas and Nekropsi, two bands that began in the 90s and have kept it up to this day, as well as ZeN who’s from the same period which disbanded a long time ago.

What about nationally and internationally?

Işık: Well that’s a question with a very broad scope. We’ve mentioned a lot of bands throughout this interview. Other than those, at this moment I can remember and name The Invisible Hands, Dead Skeletons, Rangda, Om, Malaikat Dan Signa, The Cyclist Conspiracy, Cloud Becomes Your Hand, Debo Band, Guerilla Toss, Flower-Corsano Duo, La Femme, Tara King T.H., The Budos Band, and Secret Chiefs III. Most of these are American acts, so I’d guess you’re probably aware of many of them. South American psychedelic-electronic music based on local styles is another very productive scene we should keep an eye on these days I think, like The Meridian Brothers. And we should probably delve more into China. There’s a huge music market there and we have next to no idea what’s going on in that part of the musical world. A friend who lived there for a while told me there’s a huge noise rock scene in Shanghai and I’ve spotted a few contemporary psych rock bands on the Internet recently. There’s just so much music happening in the world…

Thank you so much for taking the time to do this interview. I know it wasn’t short, but it was awesome learning so much about Hayvanlar Alemi and hopefully you all had at least a little fun reminiscing over times past. Before we go though, I’d like to open the floor up to you all for a moment. Is there anything I could have possibly missed or that perhaps you’d just like to take this opportunity to talk to me or the readers about at this point?

Işık: Well I don’t know if anything is missing above other than some obscure dark corners of our musical autobiography! Thanks a lot for your interest in Hayvanlar Alemi and letting us express ourselves through this interview.

– Roman Rathert

DISCOGRAPHY

(2007) Hayvanlar Alemi – Gaga – CD – 003 Records (Limited to 1000 copies)

(2008) Hayvanlar Alemi – Demolar 2007-2008 – CDR – Self-Released

(2009) Hayvanlar Alemi – Demolar 2008-2009 – CDR – Self-Released

(2010) Hayvanlar Alemi – Guarana Superpower – CD, 12” – Sublime Frequencies Records (12” limited to 1000 copies)

(2010) Hayvanlar Alemi – Visions Of A Psychedelic Ankara – CDR – Self-Released

(2012) Hayvanlar Alemi – Yekermo Sew – 7” – Sublime Frequencies Records

(2014) Hayvanlar Alemi – Twisted Souvenirs – 12” – Unrock Records (Limited to 400 Black Wax Vinyl copies and 100 Clear Wax Vinyl copies)