Auralgraphic Entertainment: Dreamies | Interview | Bill Holt

The 1973 home recording project by Bill Holt, The Dreamies, demands re-evaluation within the historiography of electronic music.

Its lo-fi aesthetic and pioneering sonic architecture position the album as a critical, accidental precursor to formalized electronic genres, challenging the established chronological dominance of institutionalized artists. Holt’s significance is rooted in his temporal precedence and do-it-yourself (DIY) praxis. He accomplished sophisticated avant-garde moves years before figures like Brian Eno and Kraftwerk using rudimentary domestic equipment. This reliance on technological limitation, prioritizing conceptual execution over professional fidelity, firmly situates his work within the overlooked lineage of outsider electronic music.

The album functions as a powerful cultural artifact, its unsettling, fragmented electronic soundscapes embodying the dystopian undercurrent and Cold War anxieties of the era. This early application of domestic electronic techniques and socio-political contextualization secures the project’s essential inclusion in 1970s experimental music discourse.

“Album was inspired by my love for music and world affairs”

Thanks for taking the time, Bill, to talk about your project from the 70s. Tell me about the beginning of this project. Who was behind it, and what was your intention, or should I say, your concept? I read that you had intended to redefine people’s notions of “pop music.”

Bill Holt: Thanks for your interest in my 1974 Dreamies album. It is so great that we now receive some royalties from iTunes and other purchase sites. It is not much, but it sure helps. I can tell you we appreciate each and every person who buys my music.

That first album was inspired by my love for music and world affairs, especially politics. Between 1960 and 1974, both music and politics radically changed. We went from innocent doo-wop rock and roll to dark psychedelic music. In politics, America went from straight-laced traditions to the Age of Aquarius, from quarts of beer to pot smoking.

It might all seem old now, but at the time it truly was a great American cultural revolution. I felt compelled to somehow tell the story and capture what was happening. The concept, my intention with ‘Dreamies Program Ten and Program Eleven,’ was to record for posterity a sense of those times. It was certainly not a documentary, but more a way to convey the feeling of that era — political propaganda and a time capsule all rolled into one.

What did you do before this project?

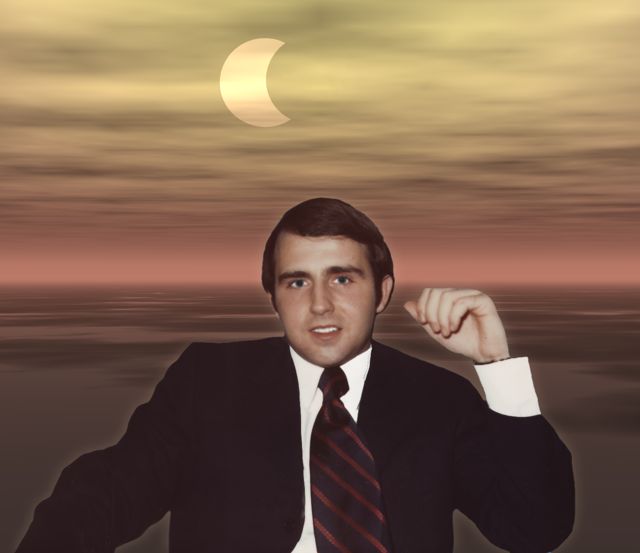

I worked for 3M Company in Philadelphia as a sales and marketing junior executive, wearing a three-piece suit. That was in the 1960s. If you know the TV show Mad Men, that was me.

“My instinct was to be original.”

How did you come up with the idea to start a musical collage, and what would you say had the greatest impact on you in terms of influences?

My instinct was to be original. I was a big fan of original art, from Picasso to Bob Dylan to the Beatles. I wanted to do with sound recording what René Magritte did on canvas. A lot of what influenced me I read about but never actually listened to.

I read about avant-garde composer John Cage. I read about concepts like musique concrète. ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ had music playing backwards, and I was amazed by the no-holds-barred Revolution 9. The track name Dreamies Program Ten is an homage to Revolution 9.

I felt that was where my talent lay. I was not a virtuoso musician or a great singer, but I felt very confident about originality. I trusted my love for composition and producing would carry me through, even though I had little experience as a musician and no experience with a keyboard.

The whole album reflects the dreams of a young man caught in the middle of the Cold War. Would you like to tell us more about the story you had in mind?

The Dustin Hoffman movie The Graduate pretty much sums up my life in the early 1960s, except for the Mrs. Robinson part. I was a young man raised in a seemingly one-dimensional world. Catholic school, with a life pretty much pre-packaged: follow the rules, play ball, get a job, make a car payment, get a mortgage, and that was that. A life very much like a frozen dinner, all prepared for you by others. Then, out of the blue, that orderly world was shattered.

The shattering began with the assassination of President Kennedy. It was a shock to the nation, even greater than 9/11. Totally surreal and unimaginable. The innocent world of Bill Haley and the Comets started to unravel very quickly after JFK was killed.

Then came the Vietnam War. I received news that my friend from high school had ended up 10,000 miles from our picture-perfect suburban hometown, carrying a machine gun in some godforsaken jungle, where he was stabbed to death by a bayonet. Meanwhile, I was back home learning how to sell office equipment for 3M, wondering why I was safe and he was dead in the jungle.

Music changed just as radically. One day I was listening to the Beatles singing I Want to Hold Your Hand, and the next day it was Buffalo Springfield with that eerie message: “Something’s happening here, what it is ain’t exactly clear.” Sgt. Pepper, Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds — a lot different from Little Anthony singing Why Do Fools Fall in Love.

It wasn’t just music that was changing. People were changing. I felt compelled to tell the story, or at least try to capture the essence of what was happening.

One thing that amazes me is that you used so many random pieces, yet they seem somehow connected. How did you choose these pieces, and where did they come from?

The centerpiece of ‘Program Ten’ is the excerpt from President Kennedy’s January 1961 inaugural address: “We are the heirs of a great revolution. The rights of man come not from the generosity of the state but from the hand of God.”

Back then, before communism collapsed, it was a real, actual threat. The Soviet Union and the USA each had tons of hydrogen bombs, confronting each other. The battle between our ancestors’ dream and Marxism was very real to me and still unresolved. It was stirring and deeply emotional.

Those sound bites — the Beatles, JFK, Walter Cronkite — are all the voices of the times. Today, I laugh when I hear people throwing around words like Marxism or communism, accusing President Obama of being a Marxist. It sounds so ridiculous. That war was fought and won last century.

When you heard, “We interrupt this program to bring you a special news bulletin,” that was happening for real, all the time. We were on edge constantly.

“We interrupt to tell you the President was shot to death.”

“We interrupt to tell you Martin Luther King was shot to death.”

“We interrupt to tell you the Soviet Union has atomic missiles in Cuba aimed at Washington, DC, and the world might be coming to an end soon.”

All those sound bites I put into Dreamies were carefully chosen. There’s material most listeners probably don’t even recognize:

The jury verdict for Jack Ruby, the man who shot Lee Harvey Oswald.

Combat sounds from Vietnam.

President Lyndon Johnson asking for God’s help after Kennedy was assassinated.

I recorded many of them myself by meticulously taping long stretches of TV news over the years. I even recorded environmental sounds: crickets at night, breaking glass, and popcorn popping on the stove while I stood by with a microphone.

It might sound bizarre now, but at the time, I absolutely felt like I knew exactly what I was doing. I was completely driven. I wanted even someone getting stoned while listening to Dreamies to subconsciously absorb the message: “We are the heirs of a great revolution.”

Remember, back then, communism was real. The USSR was bellicose, openly saying they would bury us. Today it’s more of an intellectual concept, but back then, it was terrifyingly real.

Mainly, though, making Dreamies was great fun. Choosing sound bites, deciding where to place them, and figuring out how much to reveal was incredibly exciting for me as a new composer.

The boxing match you hear at the beginning of ‘Program Ten’ progresses throughout the track, and at the very end, there’s a knockout. It was all carefully constructed. Looking back, I often wonder, “How did I do that?”

Where did you record this album and what gear did you use?

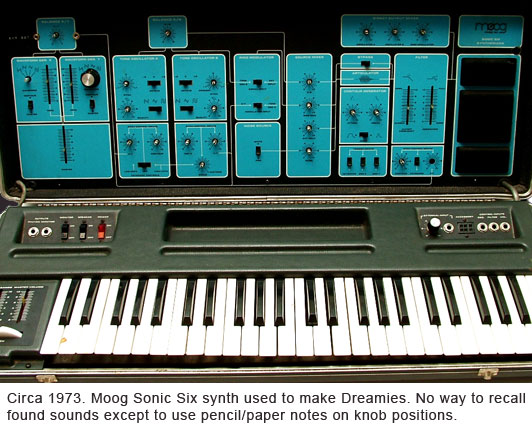

I recorded ‘Dreamies Program Ten’ and ‘Program Eleven’ in the basement of my home in Claymont, Delaware. I used an Ovation acoustic guitar — I saw Glen Campbell playing one on TV — and a brand-new instrument at the time, a Moog Sonic Six synthesizer.

In 1974, nobody even knew how to pronounce the word “synthesizer.” When I went to buy my Sonic Six, I started talking to the guy at the music store and got tongue-tied. I realized I had never actually said the word out loud. I learned to love that Sonic Six, twisting those knobs to make new sounds.

I had two good tape recorders: a TEAC 3440 four-track and a Revox two-track. I heard the Beatles used a four-track for Sgt. Pepper, so I figured I was set. I had an array of mixers, a first-generation drum machine I rigged up myself, and splicing gear to cut and edit tape the old-fashioned way: slicing and gluing pieces together.

It was a labor of love, but still a lot of labor.

Was it recorded entirely at home or partly in a studio?

At home.

Who backed you up for this project?

Hmmm, I better not forget anyone, but I believe the answer is nobody. This was a one-man project from start to finish. My loving wife Carole supported me completely, even though Dreamies slowly caused us to slip from being an upwardly mobile middle-class corporate couple to starving artists with past-due bills and no job.

You accomplished something really unique. Artists like Brian Eno and Kraftwerk made similar moves three years later. How did you manage to produce these sounds using just amateur recording equipment?

I was using consumer or maybe semi-pro gear. The biggest hurdle to overcome was noise. I am not sure if people today even relate to that problem in the digital age.

With tape, if you filled up four tracks, then recorded them onto a two-track, and then put that mix back onto two of the four tracks, the sound quickly degraded with hiss and white noise.

Professional studios had expensive Dolby noise reduction to solve that problem, but I could not afford it. I was always nerdy, so figuring out the mechanics of the gear and engineering my way around problems was fun for me.

Even today, when I hear Dreamies, I sometimes wonder how I managed to do it. Mostly it was like so many other things: lots of time, attention to detail, a love for what you are doing, and tons of hard work. Before you know it, you’ve made something good. Looking back, it feels like a small miracle.

You released the album on your own private label called Stone Theatre. Tell me about this label and where and how many copies you had pressed.

I do not recall searching for a label. I was so determined to do this on my own.

I learned good business skills from ten years at 3M in Philadelphia. I learned a lot about how different businesses work — from meat packing on Callowhill Street near the river to Discmakers, an old-school vinyl record pressing factory down in the industrial section with big vats of hot plastic turned into records.

I created the original 1974 label Stone Theatre. That is now Wilmington Studios. Stone Theatre was a typical hippie name for the times. It seems a bit overt now.

The initial pressing was 2,000 copies. At Discmakers, I had the good fortune of meeting the very savvy Ballen brothers, Morris and Larry. They were about my age and were taking the business over from their father.

Discmakers was big back then and is even bigger today. They pressed the Philadelphia sound back in the day. Morris and Larry took me under their wing, made sure I had a distributor, got me interviews, and helped me get play on local progressive stations. They were totally connected, and that helped a lot.

How about distribution? I heard some were sold through Rolling Stone magazine.

Dreamies was distributed to record stores in the Philadelphia region, plus I ran little mail-order ads in Rolling Stone. I would get orders at my P.O. Box and mail them out.

It was exciting. It was all things wrapped into one. Mainly, it was a wonderful fulfillment as a newly minted artist on a mission, while at the same time satisfying my business side.

I wanted to make a living for my family by selling my records. I did not need much — maybe sell 500 or so a month and make enough to pay the bills.

Morris and Larry were very encouraging. They liked Dreamies and even offered to buy full-page ads on the back of Rolling Stone in return for half the profit. I was too self-contained and too stubborn to say yes. I should have.

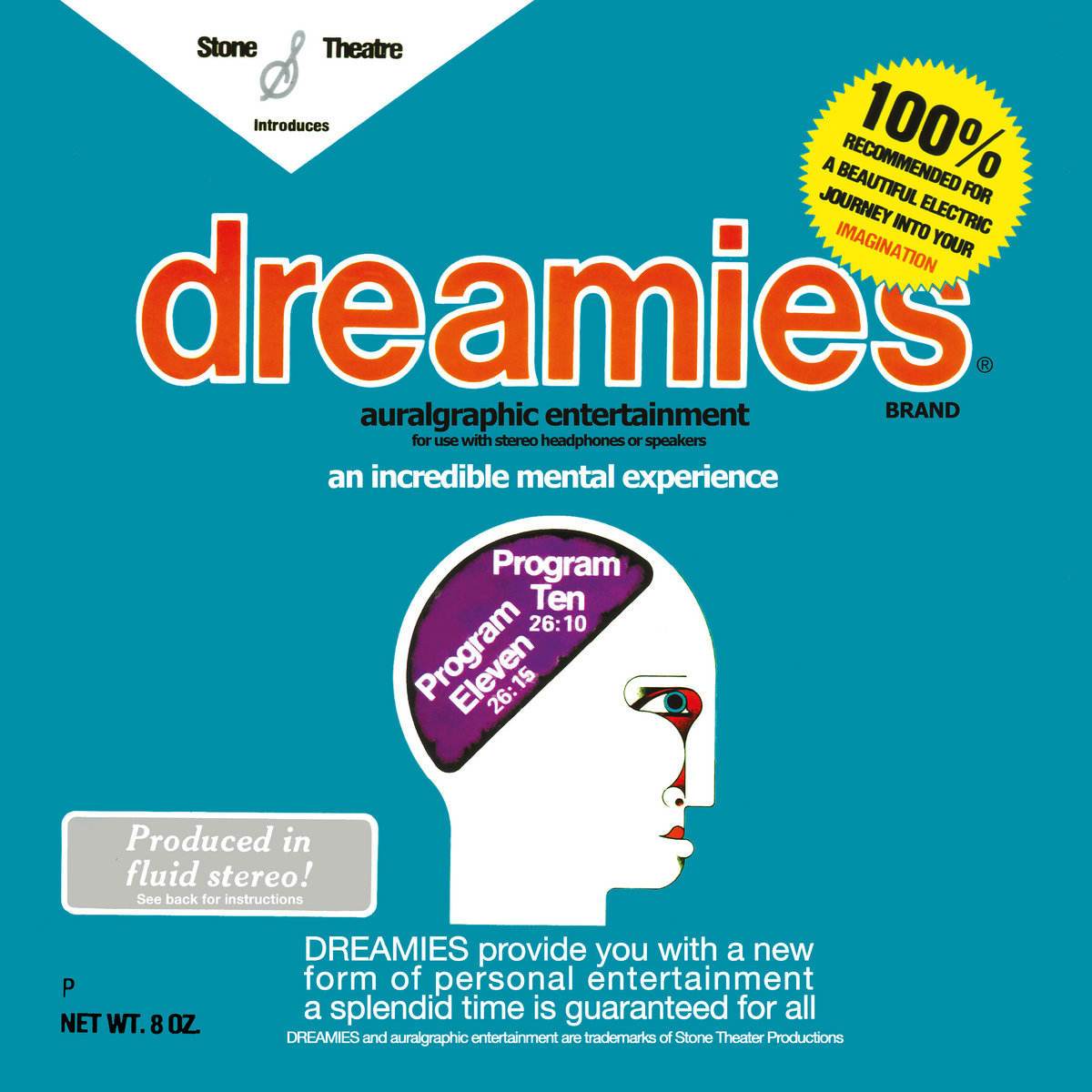

What can you tell me about the cover artwork? What does it represent?

I commissioned a Philadelphia ad agency that did work for 3M to design the cover. I told them I wanted it to look like a far-out box of General Mills Total cereal — my parody of commercial music at the time.

Funny how people love or hate that cover. I guess you could say the same for Dreamies. Sometimes I look back and think I should have used more conventional cover art. Maybe me brooding in candlelight over my Sonic Six, something more human. But it is what it is. At the time, I thought the cover was absolutely perfect.

Did you get any response from the people who bought the record or from critics back in the day?

Critics were very kind. All I heard were good things, as I recall. Someone even wrote “endless hours of enjoyment.”

I would get letters from all over, including Europe and Japan. It was pretty amazing. Not a huge barrel full of letters, but a steady stream of people sending notes thanking me and saying what a great listening experience they had.

Nothing makes a person happier than being appreciated. I was very happy with what I heard.

Auralgraphic Entertainment and Dreamies — how did you come up with these names?

Auralgraphic Entertainment was a word grouping meant to express “sound visions.”

I got the name Dreamies from an old science fiction short story by Isaac Asimov. Asimov wrote Dreaming Is a Private Thing, a story in the mid-1950s about Jesse Weill, a man who made a living selling manufactured dreams.

Asimov called those dreams for sale “dreamies.”

At the time I titled my album, I did not know that. When I later discovered the Asimov connection, I was floored because that is exactly what I was trying to do — manufacture dreams to share with others.

The album has two long songs, ‘Program Ten’ and ‘Program Eleven,’ both over 25 minutes. Would you like to go in depth about how you crafted and created them?

Just before I left my other life as a junior executive at 3M, I wrote Sunday Morning Song, which turned out to be the centerpiece of Program Ten.

The song came to me in full in about a half-hour. I love that song. It gave me the confidence to go ahead with the project. It is a seven-chord song, mainly in a minor key. Great to strum, starting with A minor.

The album was not storyboarded or planned. It was more of a stream-of-consciousness project. I worked almost every day and night, totally absorbed.

‘Nighttime’ was mainly the creative part — late at night, all night long. I was around 30 years old and had just been introduced to marijuana for the first time.

Up until then, I was a clear-eyed Catholic school corporate guy. But I knew that all the great artists had a little creative help from their friends.

So late at night, I would have a nice buzz on, full of energy, down in my studio, with all my new gear, lights low, guitar on my lap, all inspired.

The next morning, wide-eyed and sober, I would set about the hard labor of editing tape, mixing, listening, and making notes.

Then late at night, I would return to the creative flow. That cycle went on for about a year. Finally, something told me Dreamies was done.

One of the most difficult parts was listening to my own voice. I never got used to it and never really liked it.

Some of the synth buzzing and sound bites are layered over my vocals as a way to cover them up. A lot of the clicks and clacks are timed at exact intervals. There might be a sound from my homemade drum machine inserted at exact two-minute intervals using a stopwatch. The ticking of that stopwatch is heard throughout the recording.

Even though much of Dreamies may sound chaotic, a lot of thought went into perfecting techniques to give continuity and structure without being too repetitive.

Mostly, I loved what I was doing — loved expressing myself and telling the story I wanted to tell, even though it is rather opaque.

Dreamies is a story, which is why there are touches of children’s nursery rhymes woven into it.

What happened after the release of the album? What were you doing in the late 70s, 80s, and beyond?

After going from upwardly mobile to downwardly mobile, when I realized my plan to make a living selling “dreamies” like the man in Isaac Asimov’s story was not going to work, I had to regroup.

I saved enough money to last about two years and took some odd jobs, but by 1978 I was behind on my mortgage. A bill collector from Sears even came knocking at my door. That was humiliating for a former pampered 3M “mad man.”

So I made a total departure from the hippie musician lifestyle and went back to the clear-eyed, hardworking world I knew most of my life. Thankfully, I was able to get back on my feet in about five years.

Part of making Dreamies involved wiring together my studio. I have always loved electronics — figuring things out and wiring them up.

In 1978, I started my own company installing something brand-new at the time: home alarm systems. Wiring up houses and figuring out how to rig switches and circuits.

Eventually, my son worked with me, and we ended up with a successful business installing high-end home sound systems, alarms, and home theaters.

Along the way, I was fortunate enough to invent and patent several very successful alarm switches. I ended up running a successful manufacturing company.

God bless America. I am very thankful.

I was so naïve in the late 60s and early 70s. I actually thought being a poor artist with total personal freedom would be a happy, honest alternative life.

I have earned good money, and I have been dirt poor. I am convinced earning good money is better.

I now mix video art with politics on my website: www.dreamies.com

You released another album called’ Program Twelve (The End Is Near)’. What can you tell me about this one?

‘Program Twelve’ is a time capsule story about the September 11, 2001 attacks and the paranoia that followed.

In the mid-1990s, I pretty much repeated what I had done in the mid-70s. I built a home studio and purchased state-of-the-art recording equipment. I wanted to revisit the Dreamies concept with all the modern digital gear, which is so much better than analog tape.

I started ‘Program Twelve’ as an abstract piece, like a collage of memories, then September 11 happened. That changed everything.

The whole nation changed after September 11. Our innocence was stripped away overnight, similar to what happened to my generation after JFK was assassinated.

After 9/11, everything became dark, surreal, and scary. I knew then I had to tell that story, too.

The entire album is built around that event and ends with the haunting, surreal message: “The End Is Near.”

Do you have anything new planned for the future?

My dream has always been to present a live Dreamies performance, complete with video art. I have been experimenting with mixing live musicians with a multi-screen video backdrop, like Pink Floyd meets Andy Warhol.

I am not sure if that dream will ever be fulfilled, but I would love to make it happen.

Klemen Breznikar

A short while ago I discovered "Dreamies" through that wonderful cornucopia youtube and purchased a re-issue. Just run it on my turntable and boy … it's so gorgeous and awesome! Rarely heard another record that hit so perfectly the state of my younger, psychedelized self! Ready to escape to outer space worlds on the one hand, saddened and worried about the (already then) alarming state of the REAL world contrariwise. It's been a long time since I listened to a whole album concentrated in one piece and without any distraction. This album managed to get me into that rare situation again! Thanx, Bill Holt, for taking the risk!

It's great you featured Bill Holt Klemen, he's one of the most fascinating experimental artists.