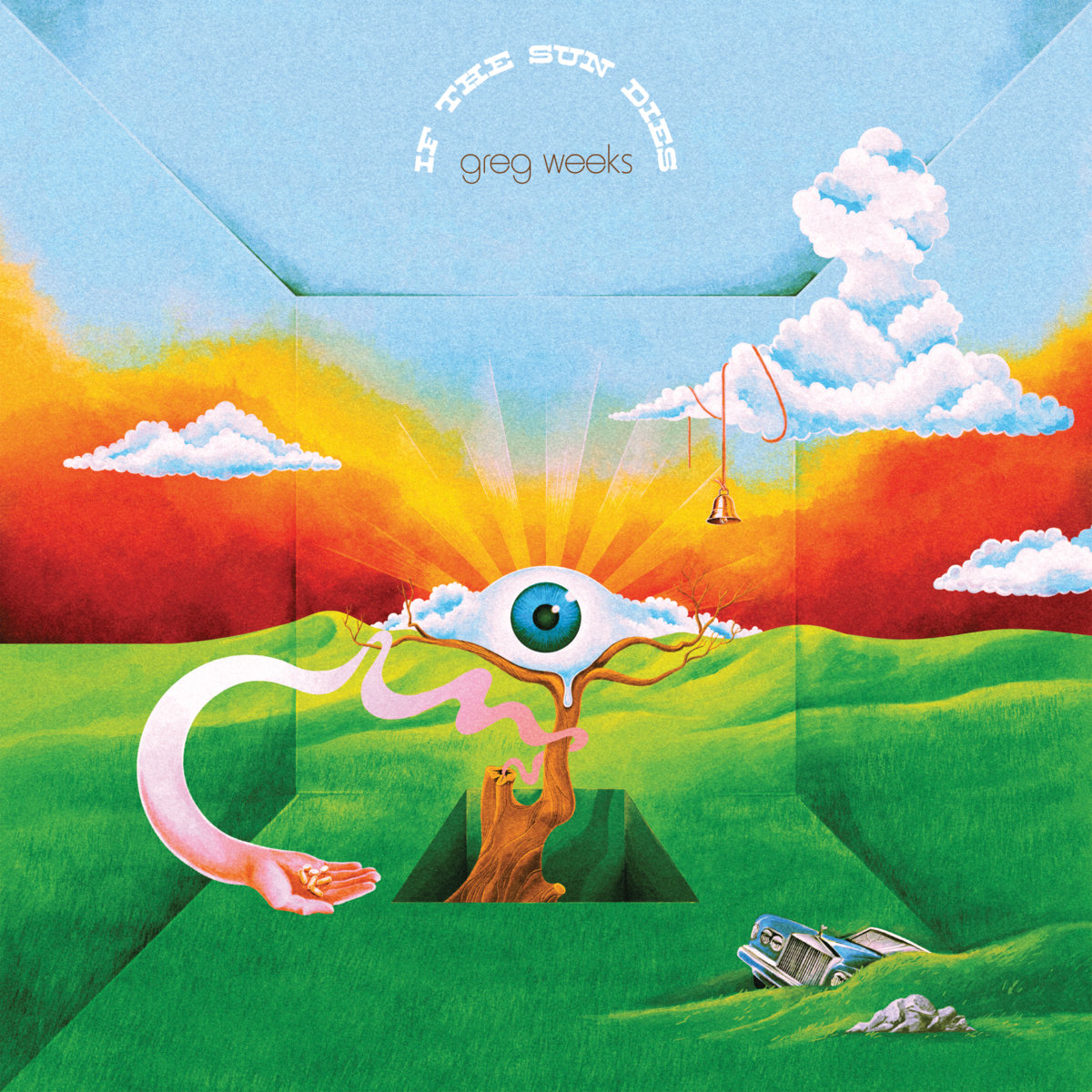

‘If the Sun Dies’: Espers’ Greg Weeks on Tape, Tradition, and the Human Trace

After nearly two decades away from solo work, Greg Weeks returns with ‘If the Sun Dies,’ an album that announces the arrival of a musician refined by years of experience.

Known as a founding member of Espers and a central figure in the New Weird America movement, Weeks has always approached recording as a ritual. That philosophy runs through every second of the new record, from its analog textures to its patient, deliberately human pacing.

Weeks has long resisted the uniformity of digital production. “Analog recording for me is equal parts textural and philosophical,” he says, describing his preference for tape as a conscious aesthetic decision. Tape hiss, slight distortion, and the occasional performance imperfection are not flaws to be corrected. They are signs of presence. “Perfectionism is the enemy to my process. I welcome the mistakes,” he explains, noting that those small irregularities allow listeners to “hear the actual person on the other end of the process.”

The album’s lead single, ‘The Heathen Heart,’ captures that ethos clearly. Built with a minimal arrangement and recorded with an emphasis on immediacy, the track drifts between melancholy and quiet resolve, reflecting Weeks’ belief that limitation often sharpens expression. Working with fewer options, he says, “keeps you nimble,” pushing songs toward instinct rather than endless revision.

The title ‘If the Sun Dies,’ borrowed from an Oriana Fallaci book that happened to sit in his daily line of sight, carries a note of dark humor as well as cosmic reflection. Yet the album’s emotional core remains very much intimate. Written after a long period devoted to family life, teaching, and other creative pursuits, these songs feel grounded and quietly determined to reconnect with the ritual of making music. With it, Weeks offers something slower. A record shaped by hands, tape, and most importantly, human trace.

“Perfectionism is the enemy to my process”

We can view this body of work as a stand against the uniformity of modern music, embracing tape hiss and distortion as evidence of human life. Could you talk a little about how these sonic imperfections connect to the spiritual truths you want to express? Is it mainly about capturing an analog sound, or is it more about a wabi-sabi approach, finding beauty in the fleeting and the incomplete?

Greg Weeks: I’d like to think that my songs are mostly complete. It is easy to see the limitations of analog recording as imposing an incompleteness on the work, but there are plenty of time-honored workarounds to track limits (though I haven’t needed them). That said, I support forced limitations in art. I think it is healthy to have to problem solve and self-edit. Maybe that comes from my English background—constant refinement of text until a kind of minimalist perfection is achieved.

Analog recording for me is equal parts textural and philosophical. Tape doesn’t provide a faithful reproduction of sound. Digital is far better suited for that. I grew up loving the sound that tape imparted to the records of the time, even as it got cleaner and more true to the source instruments. It’s kind of like deciding whether you want to reproduce an image with an unfiltered, unmodified photograph or via a watercolor painting. I choose the watercolor. It’s just a preference. I have no problem with people recording digitally. If that’s the sound someone wants, then go for it. It’s the endless tracks, the penchant for fixing each and every mistake, and the lure to endlessly labor over a project that turns me off. And more than that, it has proven to be a dangerous avenue for the culture at large. That uniformity you speak of, that’s the rub.

You stepped away from music entirely after the 2008 financial crisis and didn’t return for seventeen years. Since you see music-making as a ritual, how did that time away shape your perspective? Was the silence a kind of necessary fallow period, and what specific moment, or maybe the long stretch of writing books during lockdown, made it feel essential to come back to the tape machine?

Creatively, I was kind of ruined musically after the last Espers record slumped, ‘Language of Stone’ collapsed, and my album ‘The Hive’ vanished into the aether (it never was released in the States). On the one hand, making music felt like shouting into the void. Nobody out there seemed much to care, which, after twelve years of trying, was quite dispiriting. But the general atmosphere was one of total collapse. Nothing seemed to be working. Album sales were declining due to file sharing, labels were tightening their belts (thus Drag City severed the cord with ‘Language of Stone’), touring was becoming harder with people avoiding shows to save money, and booking agents likewise tightened their already tightened belts. The final straw was the collapse of Hexham Head, my recording studio. I had purchased a recording console that turned out to be a lemon. With no funds to get it working right, and no techs around to attempt those repairs, I had to throw in the towel. On top of all of this, my wife and I decided to start a family. Priorities shifted. Music as a living was no longer an option.

I think, at the time, I lost track of how important music-making was to my life and identity. More so, not making it was too painful, so I shut the door, locked it, and threw away the key. I attempted to write something every so often, but I had no inspiration, nothing flowed through me. So, no, the period wasn’t necessary, but it did, seemingly, allow for something to build in me, for, eventually, material burst forth like freshly tapped oil through a rig.

I honestly don’t recall the moment where everything shifted, but it started with Espers. One day I sat down and wrote a song that was decidedly Espery, and that was it. Songs just poured out of me. I wrote nearly twenty possible Espers songs. Then I turned my focus inward.

The album title, ‘If the Sun Dies,’ comes from an Oriana Fallaci novel. Her work often explores the tension between human ambition and cosmic insignificance, especially against the backdrop of the Apollo space program. How does that tension, the grandeur of space exploration and its ultimate futility, influence the inner world of your songs? Is the idea of the sun dying a metaphor for something personal?

I like to think of myself as a pretty good interviewer. I’m especially proud of the multiple interviews I did with Chan Marshall back in the 90s. Fallaci’s Interview with History is the text that really blew my mind. It provided a template for interviews that I modeled, either purposely or involuntarily. It led me to explore her other titles, which in turn led me to ‘If the Sun Dies.’ That book isn’t especially influential in terms of my subject matter, philosophically speaking, but seeing it daily on the bookcase lodged the concept in my mind. Now, having kids is all-consuming at times. As such, my wife and I often find it challenging to carve out alone time. So, the joke is a bit of dark humor indicating that when the sun dies we will finally have some time to ourselves.

Bringing back the Language of Stone label as a response to the dehumanization of modern music feels like a kind of manifesto.

Exactly. I half jokingly suggested forming a musical movement akin to Lars Von Trier’s Dogma movement, called Dogma 2025. Von Trier’s rules scratched away at much of the artifice of Hollywood filmmaking. Dogma 2025 would be a set of rules that would attempt to preserve the humanity in music-making, to scratch away at the artifice that stains so much music these days. Language of Stone sits nicely in that world, given that the label is only interested in releasing works that align to such standards.

“Folk existed before post-modernism and, I think, transcends it.”

Beyond your own work, what qualities or values make an artist a good fit for the Language of Stone? Do you see the label as creating a new canon, or more as a refuge for those committed to the analog approach?

Post-modernism got it right. Everything that can be done has been done. Everything nowadays is pastiche. So, I don’t see anything that I’ve done or will do as being unique. If anything, I champion the idea of folk. The passing down of tradition. New Weird America was, in my mind, all about that. We were all obsessed with the 60s and 70s folk, psychedelic folk and experimental music bands (and filmmakers), just as the 60s artists were all about preserving and interpreting the blues and folk styles that preceded them. In that way, we are outside of the post-modern perspective, for folk existed before post-modernism and, I think, transcends it.

I think any artist who approaches their art as an extension of the past, and whose sound appeals to our (the label’s) ears, are well-suited to release on Language of Stone. Whether we can afford to release such records is another story. Things have gotten pricey. Selling even a minimum of five hundred copies is very challenging.

You’ve talked about the endless choice baked into modern life, which you push back against by embracing the limits of analog tools like tape and faders. On this record you worked very minimally. Could you explain the difference between self-imposed limitations and the freedom those limitations unlock? On a track like ‘The Heathen Heart,’ how did the lack of choice push you to be more nimble and creative?

I know it would sound very intellectual and romantic for me to wax philosophical about how limitation drove me to create the songs on this record, but space wasn’t really an issue. I never ran out of tracks. I put all of the instruments that I wanted into each of the songs. I was never left wanting. However, that may speak more to my process, which is very fast with as few takes as possible. I purposely choose not to labor over takes. Perfectionism is the enemy to my process. I welcome the mistakes, unless they are distracting. That’s the freedom that gets unlocked. That’s what allows me to be more nimble. Plus, it has the benefit of allowing the listener to hear the actual person on the other end of the process. On the Grass record, there is an amazing moment during the last song. Meara is singing, and you can hear the floor creaking beneath her feet. That, to me, adds such dimensionality to the music. People who love music love that stuff. It’s a weird form of Easter egg. But it also screams humanity, which in this day and age is of the utmost importance.

As a founding member of Espers and a key figure in the New Weird America movement, you have a unique perspective. Do you see a modern equivalent to that movement today?

Maybe it’s just that I wasn’t out there looking, but it seems to me that all the old standard bearers are doing their thing again. The time is certainly ripe for a unified musical movement that champions tradition, pushes boundaries, and rejects the crappier aspects of modern music and music-making. I think there are new musicians out there doing this work. I’m not so sure that they are a unified force. I think we need that. There needs to be a zeitgeist moment that captures mainstream media’s attention. Something that can cut through the dross that overwhelms our social media feeds, our news feeds.

In a world full of folk forms, lo-fi sounds, and a general cultural desire for slowness, what makes the weird aspect of your music different now compared to the early 2000s?

Artists today have a lot of pressure on them to take advantage of the lack of limits. The urge to conform in order to be heard and taken seriously is huge. Back in the 90s and 2000s there weren’t many options as far as how to get your stuff recorded and out there. That was the beauty of the 4-track. That was why lo-fi was a thing. Folk Implosion and the like. Today, there is no real discernible line between the big recording studios and the savvy artist with a Pro-Tools setup. Back then, however, you had to be scrappy, record quickly, and deal with the limitations of the small studio setup that some intrepid engineer had cobbled together. A lot of musicians today feel the urge to be this glossy, perfectly packaged icon. To me, that packaged pop star is the furthest thing from palatable. But I wonder, is there a general cultural desire for slowness? I’d like to think so, but I wonder…

Has the sense of psychic dislocation your music addresses just changed its appearance?

Hmmm. I don’t really feel that my songs suggest displacement, spiritually or otherwise. There is a lot of yearning in them, for sure. One thing is for sure, my lyrics haven’t changed much from the early days.

The instruments you use, like the Hammond Organ, Mellotron, and Mini-Moog, almost feel like characters with their own history.

They absolutely are! Especially the Mellotron.

When you bring in a sound from a Mellotron, for instance, are you choosing it just for its timbre, or are you also invoking the weight of its history?

Hah! Wow. I guess it is a bit of both. Like, one of my songs off the new album features a tubular bells Mellotron setting. I chose it because the song at that point needed an instrument that could cut through the other instruments in a particular way. But, in the back of my head, I’m thinking Mike Oldfield. When I use the Mellotron flute and string combination to create chords that wash, I’m thinking Ossana’s ‘Palepoli.’ In fact, when I approach distorted guitar, my north star is always Biglietto Per L’Inferno’s guitar tones on their self-titled album. So, yes, I carry the weight of history in many ways.

Your lyrics are often called cryptic and poetic… What do you value about ambiguity and non-linear storytelling in music? Do you see oblique lyrics as a way to invite listeners to co-create the meaning, filling in the emotional and narrative gaps with their own experiences?

Not that I would ever compare myself to Leonard Cohen (though I definitely use him as the standard by which to judge the quality of my lyrics), but his oblique moments are some of the purest emotional statements on record. There is something about the juxtapositioning of images and ideas that kindles the imagination, provides a type of magnetic transcendence. Don’t get me wrong, I adore storytellers like Elliott Smith, but that’s just not my style, in general. ‘Ridley Street’ was my stab at it for this record, but it is still pretty shadowy for a linear story.

Can you share what ‘Ridley Street’ means to you, and how a seemingly ordinary place can become a symbolic space within the larger, melancholic themes of your album?

There is a track on ‘Blood is Trouble’ called ‘Skelp Level Road’ which is an actual road in Pennsylvania. Ridley Street is purely fictional. It simply popped into my head as the appropriate location for the song’s story to play out. The song is about a predator. Maybe it is a sublimation of my fears for the safety of my two daughters. Or maybe it is a form of generalized anxiety about the state of the world, which is growing more predatory in so many ways. As for symbolic spaces, I’m a creature of habit. I keep returning to the same bucolic locations under glowing moons and shady trees. But, and maybe this is the folk-horror aspect creeping in, there is always something sinister lurking in these locations. Now that I think about it, there is a lot of travelling in my songs, physical or psychic. Hmmmm.

Is talking about the music just a necessary extra, or is it part of the analog concept, a way to extend the album’s conceptual texture into words?

I love talking about music, my own or others’, hence my love of interviewing. I think connecting with others is as analog as it gets, especially when it is in person. It’s a bummer that people don’t do as many phone or face-to-face interviews anymore. The back and forth between interviewer and interviewee is such an interesting dynamic. Magical things so often happen during those moments.

Picture this: your car breaks down on the road, and somehow you end up in my little town. I invite you over for a night surrounded by stacks of records (yes, I’m truly an obsessed record freak). What albums would we end up spinning? Anything goes…hidden gems, or the kind of songs that make you stop and say, “I haven’t heard this in years.” The stranger and more unexpected, the better.

What a premise! I hope there is wine involved. The entire Catherine Ribeiro and Alpes repertoire goes without saying. She is my patron saint. Roy Harper’s ‘Stormcock,’ especially ‘Me and My Woman.’ Oldfield’s ‘Hergest Ridge,’ especially side two. Mellow Candle, Comus, Bröselmaschine, and Saint Just are favorites in the folk-rock/psych side of things. The McDonald and Giles record is insanely good. I love Krautrock, especially Paternoster and Out of Focus’ ‘Wake Up’! Italian Prog from the 70s also reigns supreme: De De Lind, Quella Veccia Locando, and the aforementioned Osanna and Biglieto Per L’Enferno. I’ve been listening to the ‘Happy Rhodes’ compilation from Numero Group a lot lately. It’s so good. Judee Sill…this could go on forever.

What’s next for you?

Well, I have enough material written for a double album. I’m working on a project with Alison O’Donnell of Mellow Candle. Magus, the band I have with Jess Weeks, is coming out in a few months. Grass just came out. And, I have a project called Wyrd Way, a folk-horror novella about a folk-rock band on tour in Europe. Each time I reference a song in the book, I’ve written and recorded the song. It’s nearly done. I’m waiting on vocals from folks like Marissa Nadler and Jason Merritt from Timesbold.

Klemen Breznikar

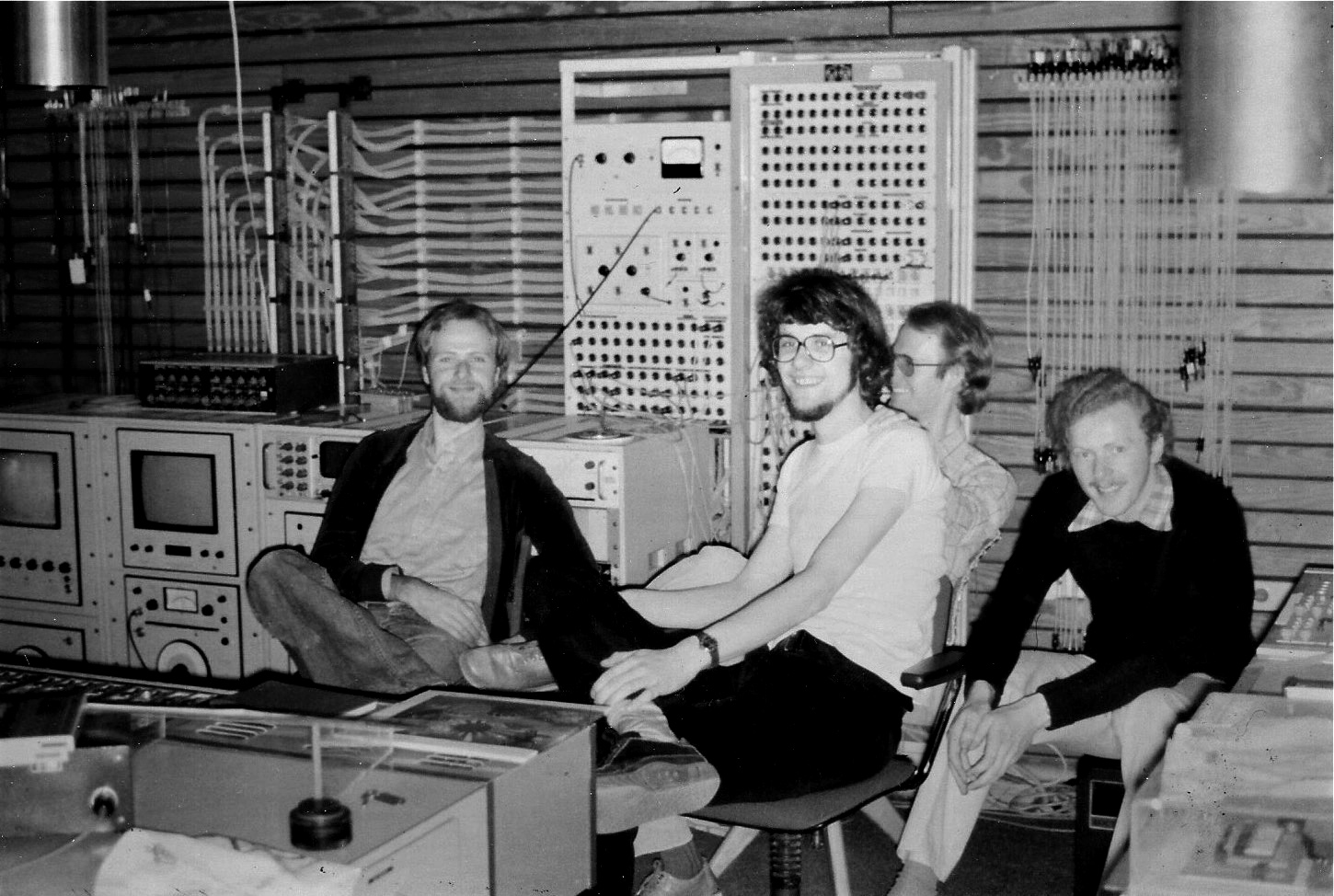

Headline photo: Greg Weeks

Greg Weeks Instagram / Bandcamp