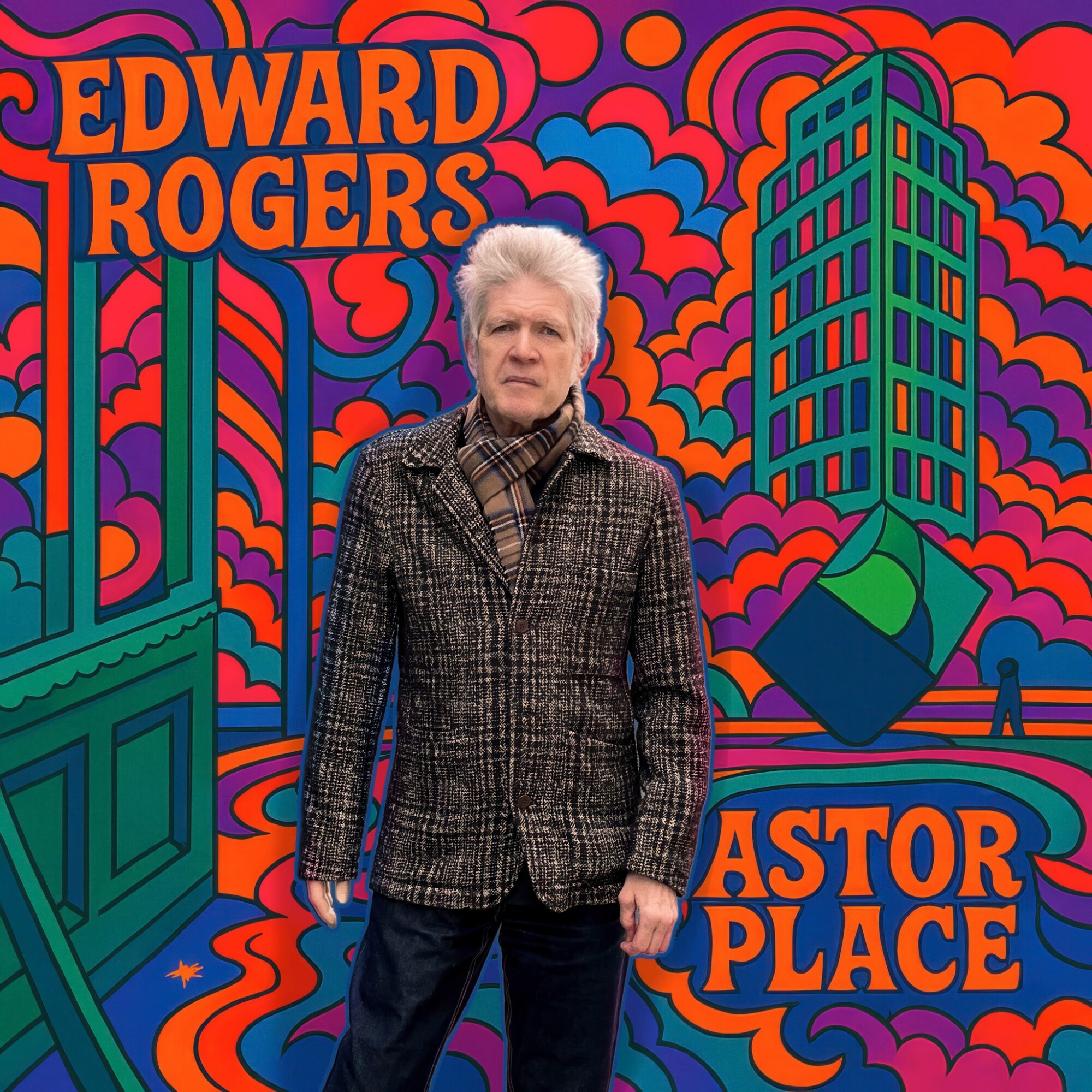

Inside ‘Astor Place’: An Interview with Edward Rogers on Life, Music, and Transatlantic Journeys

Edward Rogers’ new album ‘Astor Place’ is a journey across continents and memory.

Born in Birmingham, England, Rogers moved to New York at the age of twelve, but the streets of his childhood have never left him. His music has always balanced the precision of an English lyricist with the restless energy of a New Yorker, and this collection captures that balance with extraordinary clarity.

‘Astor Place’ was written over five years in the heart of Manhattan’s East Village, literally steps from the famous train stop that gives the album its name. At their core, the compositions are a paradoxical delight: keenly autobiographical, yet possessing that rare quality of universal applicability; all delivered through a precise, narrative lyricism and the sheer verve of live instrumentation. Rogers assembled an impressive lineup including Steve Shelley, Tony Shanahan, Matt Sweeney and Don Fleming. The decision to record live at Hobo Sound allowed the chemistry between the musicians to shape the sound organically.

Tracks like ‘The Olde Church’ reveal the English side of Rogers’ sensibility, while others showcase his ability to reflect on modern life through a New York lens. Guest musician Steve Bernstein adds haunting textures that sustain the atmosphere of the piece well past its conclusion. For Rogers, the album is a diary, a celebration of persistence, and a reminder that good music still thrives. ‘Astor Place’ is both a map and a story of a life lived across two worlds.

The album, released on Think Like A Key, is available in two special editions. The “Analog Autobiography” Vinyl Edition is pressed on 140g black vinyl and strictly limited to 100 copies. The “Birmingham to Manhattan” CD Edition comes in a six-panel digipak complete with an obi strip.

“The most universal songs spring from the most personal places.”

You’ve described ‘Astor Place’ as a journey from Eldon Road, Birmingham, to the East Village, Manhattan. A physical map, perhaps, but also a cultural one. Your music has always embodied this “transatlantic tug-of-war.” Do you now find yourself creating from a single, unified cultural perspective — a “Mid-Atlantic” identity — or do you feel you still consciously switch between the English lyricist’s precision and the American?

Edward Rogers: Since I was born in Birmingham, England, and lived there till I was 12 years old, those were very formative years where a lot was learned and stayed with me. Even after I moved to New York, I traveled back to England quite a bit, so the cultural ties remained with me. I’ve always considered myself to be an observational writer, so of course New York — and especially downtown and the East Village — influence my writing. But I often think about where I grew up and how it affected me. I still travel back to England twice a year and see the changes, especially in London, and that often shows up in a song.

Where on this album did the “Brit” in you truly battle the “New Yorker”?

I’m not sure I would say there is a battle anywhere on ‘Astor Place’. ‘The Olde Church’ was inspired by a wedding I attended in northern England, which I wrote on the three-hour train ride back to London. I guess you could say that this song, about a very English wedding complete with a brass band walking up the hill from a very old church that included the town’s cemetery, was written through a New Yorker’s eyes.

The album title, ‘Astor Place,’ anchors this collection in a specific locale. While “Birmingham to Manhattan” suggests a grand narrative arc, a single place often contains multitudes of emotion. What quality of ‘Astor Place’ — its history, its energy — made it the perfect conceptual umbrella for five years of intensely personal memories, rather than, say, a broader title like East Village Sessions?

I live in the East Village, literally steps away from ‘Astor Place’ — the train stop, the famous cube in the square, The Public Theatre. During the five years of writing the songs, I walked around my neighborhood every day. When coming up with a title for the album, ‘Astor Place’ seemed most appropriate since that’s where I wrote the songs. I don’t think this album necessarily has a theme, but it’s rather a collection of songs written during a specific period and under the umbrella of my home near Astor Place.

The recording lineup — Steve Shelley, Tony Shanahan, Matt Sweeney, Don Fleming — is amazing, particularly that rhythm section. You chose to capture this essentially live at Hobo Sound. What made you want to let the chemistry and little imperfections of the live moment shape the feel of the album?

Agree, these (and all the other musicians) are pretty great. I was lucky to work with them. This was mainly an idea that producer Don Fleming and I came up with when planning this album. There were a lot more ideas shared by the musicians in real time, and the results were immediate. That sense of freshness and live band feel was captured during those days at Hobo Sound. There’s just a palpable energy that can only be captured in a live studio setting.

Steve Bernstein’s slide trumpet and alto horn add a specific, almost sepia-toned melancholy to several tracks. It’s a striking choice against the backdrop of guitar rock. What was the conceptual or emotional brief you gave him? Was the intent to evoke a specific jazz or European cinematic feel, or was it simply to inject a different kind of lonesome voice into the arrangements?

I wish I could take credit for bringing in Steve Bernstein, but it was all Don Fleming’s idea. Once we had the basic live takes from the band, Steve provided some darker elements. We just let Steve listen to the takes a few times and record what he felt. The musicians were given a lot of freedom of musical input on Astor Place, and I think the results are in the grooves.

You state, “The most universal songs spring from the most personal places.” Take a song like “Diamonds Hidden in the Pearls.” The title itself suggests a search for value beneath an outer layer of beauty or difficulty. When you’re writing a really personal song, how do you balance keeping some things private while still giving listeners something they can connect with?

When writing a song, I’m always writing for myself first. Once it’s completed as a demo, I’ll determine whether it’s something I want to share or is a track I’d rather leave on my computer, unassigned. I think we all share a lot more than not, in general. So my personal struggles don’t have to be spelled out but can be hidden in the pearls, so to speak.

Your work with Stephen Butler is highly regarded and has a very defined aesthetic, notably utilizing the legendary space of Abbey Road. How do you mentally and creatively switch gears when approaching a solo project like Astor Place? Is the key a different melodic sensibility, a more diaristic lyric approach, or simply the freedom to explore tones that might not fit the R&B?

Primarily, when working with Steve, I provide the lyrics and he provides the music. We’ve written this way for many years. Once a basic song is conceived, he shares it with me for my musical ideas, and Steve also has the freedom to suggest lyrical changes.

I’ve always been a prolific songwriter in that I work on new music and song ideas almost every day — not necessarily for a specific project. Some songs just seem more Rogers & Butler, and some feel more in line with my solo work. Also, when working on songs for myself, I provide both the lyric and the music via the Logic program. But I do think there are songs I’ve written for myself and others Steve has written for Smash Palace that could work for Rogers & Butler.

You’re known for digging into music history on Atlantic Tunnel and Totally Wired Radio. Does constantly curating and analyzing other artists’ work change how you write your own songs? Do you get more critical, or does it just make you more aware of your musical roots?

The main reason I do Atlantic Tunnel is to try and turn listeners on to old music I love and grew up with, as well as new music that I think they might not hear if it wasn’t for the show. I also have a personal record collection — vinyl, CDs, and 7-inch singles — in excess of 10,000, so digging in every week is fun! Also, getting to hear so much new music keeps me current with ideas from all genres. I’m sure it affects my writing and shows up in my solo work.

The mention of ‘Magical Drum’ suggests a track that leans away from the autobiographical and toward the abstract or mythical. Can you share the genesis of this song? Is the story purely made up, or is it tapping into the almost magical, grounding power of drumming in modern life?

Actually, the song is totally inspired by a real-life experience. A high school friend was dating one of my best mates back then and asked me to help her find a gift that would impress him. I was searching around the East Village (yes, even back then) and came upon a store that sold Indian instruments. I thought the tabla drum was cool and suggested it to her. Decades later, I reconnected with her only to find out my mate had passed away. She still kept that drum, and as a memento of our friendship, she sent it to me as a gift. I still think it’s cool and am looking at the drum right now.

“I was surrounded by bohemian culture, but never really considered myself as that; it never really pulled me in.”

Your journey leads you to the East Village, historically a nexus of bohemian and countercultural art. To be bohemian now, in the 2020s, is a very different proposition than it was for The Velvet Underground or Patti Smith. What does bohemian mean to Edward Rogers today?

Interesting question. The Edward Rogers of today considers himself to be a bit of a Mod — think Paul Weller as well as Steve Marriott — taking the influences from the best of what I like. It’s funny, growing up in the city and frequenting the East and West Village, I was surrounded by bohemian culture but never really considered myself that; it never really pulled me in.

Of course, to this day, I still love The Velvet Underground and Patti Smith, who I saw back in the day.

Your accent remains a distinctive part of your vocal identity. In rock history, the use of an authentic, regional British accent has always been a political, emotional, or subversive choice — from The Kinks’ kitchen-sink drama to The Clash’s polemics. What significance does your accent carry in your singing? Is it a conscious anchor, an emotional register, or simply the honest sound of your voice?

After spending my primary years in England, my accent seems to be more pronounced when I’m singing. I just talk and sing like I talk and sing, so I think for the most part it’s the honest sound of my voice. As far as Ray Davies, he has been a major influence on my singing style and lyrics.

After decades of writing, recording, and performing, what is the single most important lesson you’ve learned about sustaining a creative life?

No matter how dark it gets, tomorrow is another day, and it only takes one spark to light up a dark room. I guess in a way my songs are my diary, so there’s always something to add. So, basically, don’t give up.

When the listener finishes the final track of ‘Astor Place,’ having traveled from Birmingham to Manhattan through your most intimate statements, what specific emotional residue or singular final thought do you hope they take away from the experience?

After they listen, I would like to think that they would say there is still good new music being made and play ‘Astor Place’ again! If they relate to something, even better.

Klemen Breznikar

Edward Rogers Facebook

Think Like A Key Music Official Website / Facebook / X / Instagram / Bandcamp / YouTube