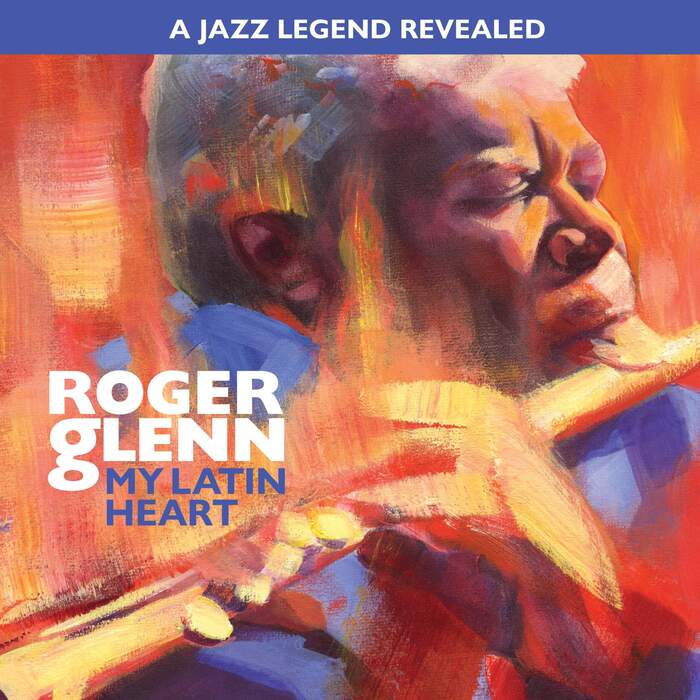

Roger Glenn Talks ‘My Latin Heart,’ Cal Tjader, and the Legends Who Shaped His Sound

Roger Glenn, a virtuoso multi-instrumentalist whose career spans more than six decades, emerges into the spotlight with ‘My Latin Heart,’ his first album as a leader in nearly fifty years.

Celebrating his 80th birthday, Glenn channels a lifetime of musical exploration into a work that is both personal and culturally expansive. The album reflects his profound engagement with Afro-Caribbean and Latin American rhythms, a passion rooted in his formative years in New York City, where he absorbed a diverse spectrum of musical traditions. A master of flute, vibraphone, marimba, and saxophone, Glenn seamlessly fuses jazz improvisation with the rhythmic vitality of Cuba, Brazil, and beyond. Backed by an elite cadre of Bay Area musicians, ‘My Latin Heart’ pays homage to mentors like Cal Tjader while advancing the lineage of Latin jazz into new terrain.

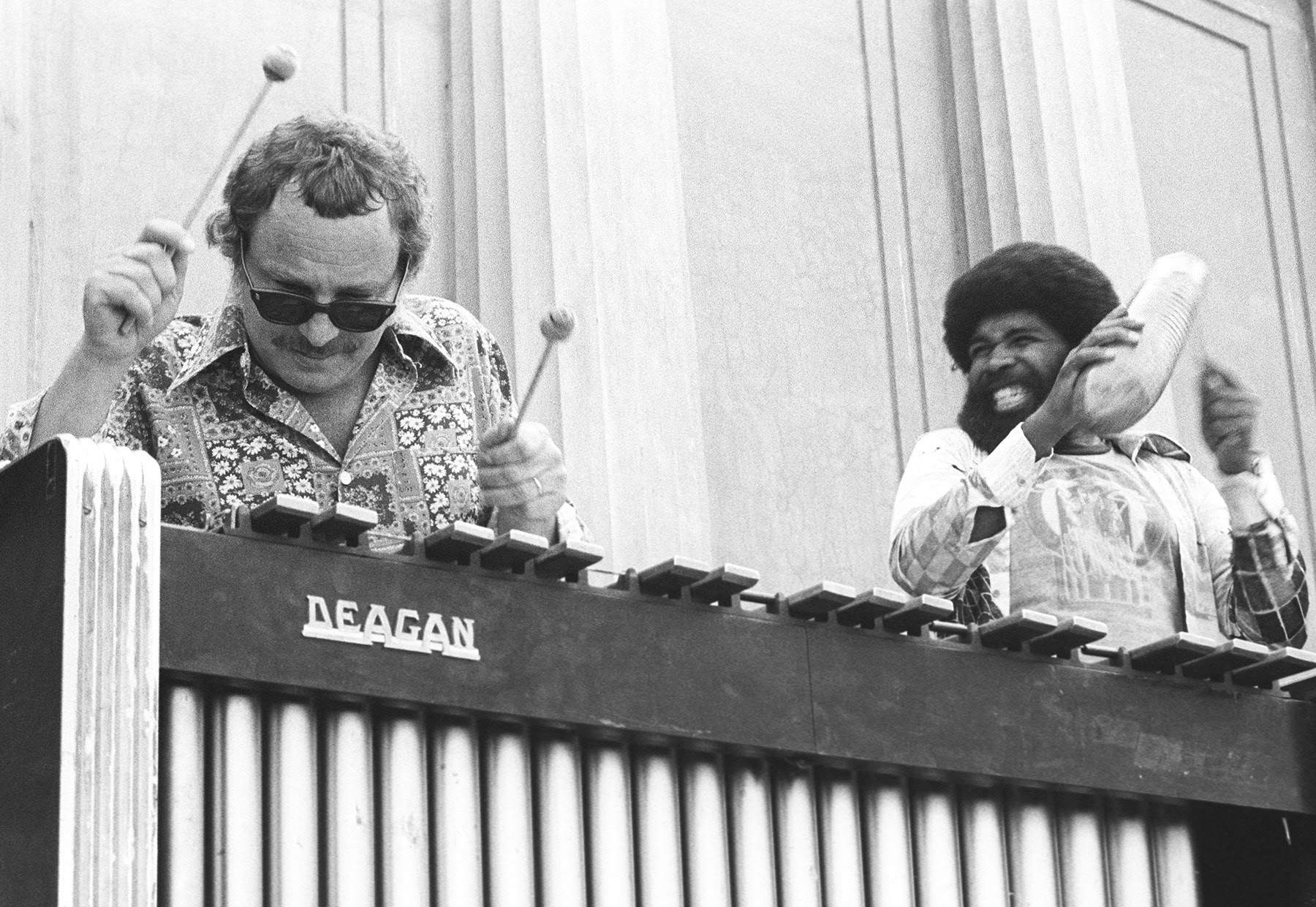

Reflecting on the Tjader centennial, Glenn says: “Getting to work with Cal was a great experience. When I first met him, he was playing at the Apollo, and I met him backstage. One day I was walking down Market Street in San Francisco and noticed that Cal was playing, so I dropped by to see him. We had played, when I was down in Monterey with Dizzy, and did some stuff at the Greek Theatre in Berkeley. So I went to see Cal and sat in on the last number of the last set. And he said, ‘That sounds great. We’re going into the studio tomorrow. Would you like to join us?’ I said, ‘Yeah, OK.’ And it was like magic. We did this album, ‘La Onda Va Bien,’ and it won a Grammy. It was a great moment.”

“I’ve always seen myself as a musician rather than a flutist or vibraphonist or saxophonist.”

‘My Latin Heart’ is your first album as a leader in a half century, and it arrives alongside your 80th birthday. Could you elaborate on the factors that converged to inspire you to step into the spotlight as a leader once again at this particular moment in your life?

Roger Glenn: As a leader, I’ve been performing locally for decades. I’ve done numerous recordings over the years for other people. Regarding my own recordings, this is the first in a very long time between the ‘Reachin” 1976 album and ‘My Latin Heart,’ 2025. I’ve had bands in various configurations for many years playing locally in the SF Bay Area. Now that ‘My Latin Heart’ is being released, people can hear it all around the world. My desire is that the music touches and reaches many people and will take us around the world. I love performing live for people, so they have the first-hand experience.

Tell us about your lifelong passion for Afro-Caribbean rhythms. This album certainly seems to be a profound expression of that connection. What specific experiences or influences throughout your career truly solidified this deep passion for Latin American music within you?

Being born in New York City and living in the NYC area, in Englewood, New Jersey, right across the George Washington Bridge, you are exposed to many cultures. I was able to hear the music of all the cultures that live and breathe there.

Let alone the fact that I grew up with my father, who was a trombonist and vibraphonist named Tyree Glenn, who worked with Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, and Louis Armstrong. So my jazz roots were initially there. Growing up, my mother Gloria loved Latin music, and that seemed to stick with me also.

New York is a multicultural area, so you get a chance to listen to and play all kinds of music. In this case, Latin music and Latin jazz, and I loved all the energy. Some of the people who influenced me were Mongo Santamaria, Cal Tjader, and Herbie Mann.

On the Cuban side, there was Cachao, a very famous bass player who had an album out that I have always loved, called ‘Cuban Jam Session in Miniature Descargas’. I found this record in the gutter, and the titles and all had washed away. I took it home and played it, and it was Cachao with his little Descargas, which was very influential.

I was in junior high school at the time, and I put together a band based on those songs we heard. Little did I know, later in life, I would be playing with him on a recording we did with Mongo Santamaria’s 1971 album, ‘Mongo’s Way’.

It was growing up in an area where you have this diversity of different sounds and music, hearing jazz from my father and other great jazz giants, as well as the Latin side. So it was the perfect storm, as they would say.

‘Cal’s Guajira’ is a beautiful tribute to Cal Tjader on the album, and you play vibes on this track. Considering your extensive history with Tjader, including your contributions to his Grammy-winning album ‘La Onda Va Bien,’ what emotions or memories did you draw upon when composing and performing this particular piece?

I guess it’s that I envisioned Cal, like we’re on the bandstand together, and he just had a way of playing on songs like that, which inspired me to write ‘Cal’s Guajira’. It’s a nice groove, for lack of another way of saying it, and it’s typical of Cal. He had that touch to make things move that way. So he was the inspiration for me to compose that song.

You are celebrated for your mastery across a wide array of instruments, including flute, vibes, alto sax, and marimba, all of which are featured on ‘My Latin Heart’. When approaching a new composition or a particular piece of music, how do you decide which instrument will best convey the feeling or message you intend to express?

I get a melody in my head, and I think about that, and I feel like, yeah, this feels like a vibe thing, or it feels like a flute thing. I don’t say, “I’m going to write a vibe song.” It’s more like the melody comes in, and I say, “This sounds like I would like to play this on vibes,” or “I’d like to play this on flute,” or “I’d like to play this on saxophone.”

And even with the saxophones, it could be an alto, a tenor, or a soprano. It’s how the melody moves me that moves it toward the instrument that I want to play on it.

Your original composition ‘Roger’s Samba’ appeared on Cal Tjader’s 1980 album ‘Gozame! Pero Ya’. How do you feel your compositional approach, particularly concerning Latin rhythms, has evolved or matured between that earlier work and the new compositions featured on ‘My Latin Heart’?

Well, I love Brazilian music. I wrote ‘Rio on my Reachin” album before I got a chance to go down to Brazil with Dizzy and have experiences there.

I was down there around New Year’s, and it’s the start of Carnaval. It goes from New Year’s to Lent during that three-month period. I really got to experience the street scene of the music and how it’s played. The streets are crowded with drums and people, and the cars are parked and can’t move because everybody’s into the rhythms of the thing.

That memory is what inspired me the second time, writing Roger’s Samba. It was about being down there and being exposed to that. I envisioned the dancers and all that. ‘Samba de Carnaval’ on ‘My Latin Heart’ has the Brazilian rhythm vibe those experiences evoked.

‘Cal’s Guajira’ is based on a Cuban guajira. I’ve been fortunate to travel to Cuba several times and even played at the Jazz Plaza there in 2019. The music and the people are phenomenal.

My composing for ‘My Latin Heart’ has all been inspired by my travels to various countries. People don’t realize the depth of diversity of the music in Latin American countries that share their own individual styles.

Each song has its roots in different Latin countries, and each song is different: playing a samba is different than playing a guajira, which is different than playing a jazz feel or a bolero. They represent different styles in different countries. I’m fortunate to be familiar with a lot of different cultural inputs.

The album features an impressive cast of Bay Area musicians, and collaborative chemistry is often crucial to the success of a project. How did the unique talents and contributions of artists like Ray Obiedo, David K. Mathews, and the late Paul van Wageningen shape the overall sound and direction of ‘My Latin Heart’?

All of us have played together for many years, alongside the likes of Pete and Sheila Escovedo, both in my bands and Pete’s band, and Azteca, going back to the 70s. We’ve played in various types of situations, and that’s why I selected them to be on this recording. I knew that they were capable of playing the varied styles of music that are on the album.

David K. Mathews now plays with Santana, which is sort of Latin rock, yet he was also able to play the classical European intro to ‘Congo Square’. Ray Obiedo has worked with Herbie Hancock, which is more of a jazz feel. David Belove brings rock-steady bass playing, and Derek Rolando on percussion plays with fire. They really understand the grooves.

Paul van Wageningen has sadly passed since the recordings, but he was THE drummer for the Latin rhythms, especially his Brazilian style of playing. We brought in Santos and Spiro for some icing on the cake for Angola and Samba de Carnaval.

We all love and respect this music in terms of Latin rhythms. I just knew they were the cats to play the various styles for my compositions.

You mention celebrating the unique confluence of European and African currents in New Orleans with your piece Congo Square. Could you discuss how this historical and cultural concept translated into the musical elements and structure of the track, and what you hope listeners will take away from it?

My inspiration for this was deep-rooted, like the trees in Congo Square in New Orleans, expressing how the two cultures coming together formed new unique art forms that could only have happened there at that time and place.

It was to show how two cultures, African and European, came together in the Americas, or in this case, specifically New Orleans, and how it evolved in the United States. The chord changes at the beginning are more of a European style, and then it moves into the 6/8 rhythms, which is more the African side of it. So it’s bringing those two cultural musical medians together that inspired me to write the song.

The place Congo Square in New Orleans was the only place where slaves were allowed to play their drums, and only on Sundays. But they were also immersed in a European style of playing, and eventually, that led to jazz of the world, and the jazz of the world led to other musical forms in the United States.

In the video I’ve created for ‘Congo Square,’ you’ll see mention of all those different styles. This was like the roots of this tree of music, and the branches branching out created different things from jazz to Latin jazz to blues. So that, to me, is what Congo Square represents in this country: an example of the elements that came together initially and what has grown from that.

“I’ve always seen myself as a musician rather than a flutist or vibraphonist or saxophonist.”

Your father, the esteemed trombonist and vibraphonist Tyree Glenn, undoubtedly had a profound impact on your musical journey. What are some of the most enduring lessons or influences you absorbed from him, both musically and personally, and how do they continue to resonate in your work today?

What was tremendous and really great was that I also had an opportunity to play with my father and the musicians he played with, who were all basically straight-ahead jazz musicians. It helped me with my jazz roots in traditional jazz, being able to love, appreciate, and practice that style of music so that I could incorporate it into my own.

They were such great musicians: bass players Slam Stewart, George Duvivier, and Milt Hinton; Wynton Kelly, who played piano with Miles Davis; Jo Jones on drums, who worked with Count Basie; and others like them.

They were influential in giving me a sensibility of what my father was playing and in me learning from those individuals while playing with them and my father. So it had nothing to do with Latin music. It had to do with the jazz side of this world in the United States.

My father gave me a sense of how to construct things. He would always say, “When you’re playing and taking your solo, you got to learn to leave stuff out. Be reserved. You only get two choruses in the solo, so make the best out of it. That’s it.”

You also shared an anecdote about meeting Cal Tjader backstage at the Apollo and later joining him for the recording of ‘La Onda Va Bien’. Could you expand on that “magic” you experienced in the studio with him, and what made that particular collaboration so creatively fruitful?

I had only played with Cal when we were guests with Dizzy Gillespie at the Monterey Jazz Festival. Obviously, he was an influence in regards to me wanting to play vibes, as well as my father, Milt Jackson, and Lionel Hampton.

So Cal and I played Monterey, and we had a sense of knowing each other better. One night I was walking down Market Street in San Francisco, and I had my flute with me. I saw Cal was playing at this club, so I went down there, and since he knew me, I sat in on the last number of the last set.

He said, “Man, that sounds great. We’re going in the studio tomorrow. Would you like to join us?”

I said, “Yeah.”

And it was magic! There weren’t any written charts. We just put these songs together and it all fit. Everybody was on their triple-A team for playing music, and we did it in three days. The next thing we knew, it was up for a Grammy, and it won a Grammy. So there was a lot of magic happening in regards to that first recording together.

You have collaborated with an incredibly diverse range of legendary artists, including Herbie Mann, Mongo Santamaria, Dizzy Gillespie, Donald Byrd, and Mary Lou Williams. Are there any particular collaborations that stand out as pivotal moments in your artistic development, and if so, why?

Well, the first recording I ever did was playing flute with the great pianist and composer Mary Lou Williams in 1969. We recorded ‘Music for Peace,’ and that was magic.

After that, I had the opportunity to work with Mongo Santamaria. After hearing him for so many years, being able to play with him was an incredible inspiration. Mongo, and also Armando Peraza, who I first heard when Cal Tjader came to New York and Armando was playing congas with him — that experience of being able to play with both of those guys, Armando and Mongo, was incredible. These are what I call “the real deals” in regards to Afro-Cuban music.

They were inspirational and educational moments. It was like the dream of a lifetime to be able to play with these guys that I had listened to for so long.

Later on, Herbie Mann was the same kind of experience. The first song I learned to play on flute was Herbie’s ‘Comin’ Home Baby’. So these guys I grew up listening to — Cal Tjader, Herbie Mann, Armando, Mongo Santamaria — it was a no-brainer in regards to feeling comfortable playing alongside them.

In a totally different genre was Donald Byrd’s ‘Black Byrd’ album that we did. Growing up with legendary composer-producers Larry and Fonce Mizell and Freddie Perren, they later brought me in to do the ‘Peaches & Herb Reunited’ album.

That’s what I’m saying about living around the New York Metropolitan area — being exposed to a lot of different styles of music. Also, early rhythm and blues and rock and roll. My brother, Tyree Glenn Jr., had a band called Tyree Glenn and the Fabulous Imperials, and they would play at the Peppermint Lounge and Trude Heller’s in New York City. I’d sit in with them.

That’s not the typical thing, having a flute in a traditional band with saxophones, guitar, and organ in that early rock and roll and rhythm and blues style. But I had the opportunity through my brother to play that stuff.

Most recently, I had the opportunity to tour and record for several years with Taj Mahal. This illustrates the depth of diversity in my playing. Having the opportunity to play with Taj solidified those roots for me.

We even recorded Taj Mahal and the New Hula Blues Band: ‘Live from Kauai’ and won a Hoku Award in 2015. To step into and play true American blues and feel that music with a treasured blues icon was monumental.

“People don’t realize the depth of diversity of the music in Latin American countries that share their own individual styles.”

Beyond your musical pursuits, you are also a pilot serving in the Civil Air Patrol, and you have engaged in scuba diving and sailing. How do these diverse passions and experiences outside of music inform or influence your creative process and your approach to life in general?

I think all of those things, whether in the air, under the water, or on the ocean, as an artist, you get these images. You get these images of life and your surroundings, and you try to interpret them musically.

Given those opportunities to do those things, from a musical standpoint, they go hand-in-hand. I will be playing something and thinking of environmental and natural things. I’ll be thinking of people, how they act, how they live.

The inspiration for the song ‘Brother Marshall’ came from when I was playing for this guy who had passed away. He was a teacher, and he worked with many of the musicians who were playing for his funeral. He had taught and inspired them.

You envision the person and who they were. People have their own rhythms within them, and when I see that, that can be incorporated into the music.

You expressed, “I’ve always seen myself as a musician rather than a flutist or vibraphonist or saxophonist.” Could you elaborate on this holistic view of your musicianship, and how it has guided your career choices and artistic explorations over the decades?

Like I said before, it’s the instrument that fits the music. The music fits the instrument. That’s just the way I think.

The album ‘Reachin’,’ produced by the Mizell Brothers, became a cult classic. Looking back at that period and the unique sound of that album, how do you perceive its place within your broader discography, and does it hold any particular significance for you now?

‘Reachin” came about as a continuation of doing the Black Byrd album. It grew out of the various grooves that were created there and applied the same technique, led by the phenomenal Mizell Brothers, to create Reachin’.

We had a chance to work on songs before we actually recorded them. We would jam based on some ideas that I had, and then we would go and record them.

I think it stands the test of time because people still love that particular album and what we accomplished there.

At the time, I was living in San Francisco, and like I said before, Ray Obiedo was playing. The great piano player Mark Soskin, who later moved back to New York City and went on to play with Sonny Rollins, was also involved. They all had that similar background and Latin feel in terms of the diversity of Latin music in Latin American countries, each with their own particular blend.

They also worked with many American jazz musicians. Ray and Paul Jackson worked with Herbie Hancock, so they had that sense as well as playing R&B-style music. Paul Jackson was just a great, funky bass player. He really set great grooves.

The composition ‘EBFS’ was based on a bassline that Paul was playing, and I had this melody that came into my head while playing. I’ve not had a bass player since who could play that line.

As someone who has witnessed and actively participated in the evolution of jazz and its various subgenres over many decades, what are your observations on the current state of Latin jazz, and where do you envision its future trajectory?

Sometimes the definition of Latin jazz has evolved into a combination of small groups versus big bands, versus something that is traditionally Cuban, versus something that’s traditionally Colombian. It’s the ability of different groups coming together.

When we speak of jazz, what is jazz? Jazz could be Dixieland jazz, it could be modal jazz, it could be bebop. We’re talking about a general style called jazz, but it involves so many different types of influences.

I think as people grow in appreciating things that come out of Latin America, as well as things that come out of the United States, it continues to grow. There’s even hip-hop in regards to Latin music, and that’s an American-based style of playing that’s been incorporated with a Latin feel.

We’re talking about rhythms, chordal progressions, and different grooves that may be R&B-type grooves with a Latin feel. When I say “with a Latin feel,” it would incorporate clave and things of that nature.

It’s progressing, and as people become more familiar with the different cultural influences in the Americas, they feel more comfortable integrating those into their compositions.

As people become more diverse in appreciating different Latin American music, from Argentina and Brazil to Mexico, the Caribbean, and the United States, there are these cross-cultural feelings. These different styles are integrated into the next steps of music.

‘My Latin Heart’ is presented as you picking up Cal Tjader’s mantle and stepping into the spotlight. What message do you hope this album conveys to both longtime fans and new listeners who are just discovering your extraordinary talent and musical legacy?

I hope this album can inspire people to learn and listen to different styles of Latin music that have been my influences. I don’t just play one style of music. I play different styles of music, and on this particular album, it’s my experiences with Latin American rhythms and styles that I incorporate so that people get a sense of the significance of the different cultures within Latin music that inspired me to compose these songs.

These songs have a Latin feel, coming from the life experiences I’ve been fortunate to have in various countries and from being inspired by many artists performing. That is why it’s titled ‘My Latin Heart’.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Cal Tjader and Roger Glenn performing at the Greek Theater in Berkeley, California (1974) | Credit: Victor Aleman

Roger Glenn Website / Facebook / Instagram

Patois Records Website / Instagram