Elliott Murphy Talks ‘Infinity’ and the Endless Road of Songwriting

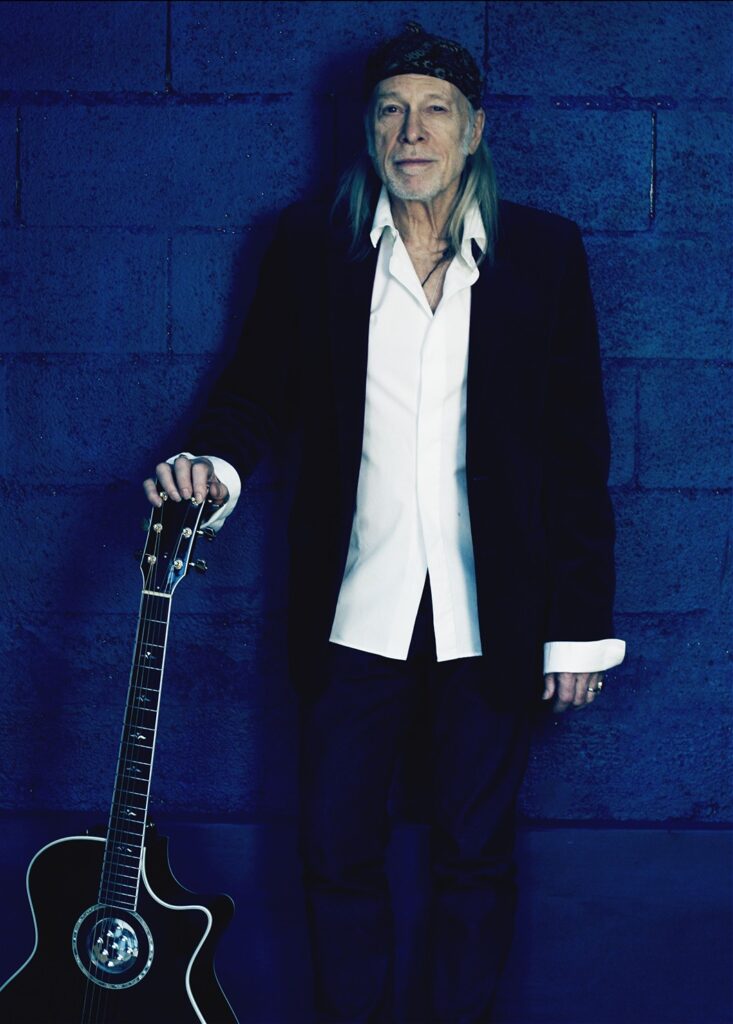

Elliott Murphy is a rare breed of artist, a storyteller whose music feels less like songs and more like chapters from a deeply lived life.

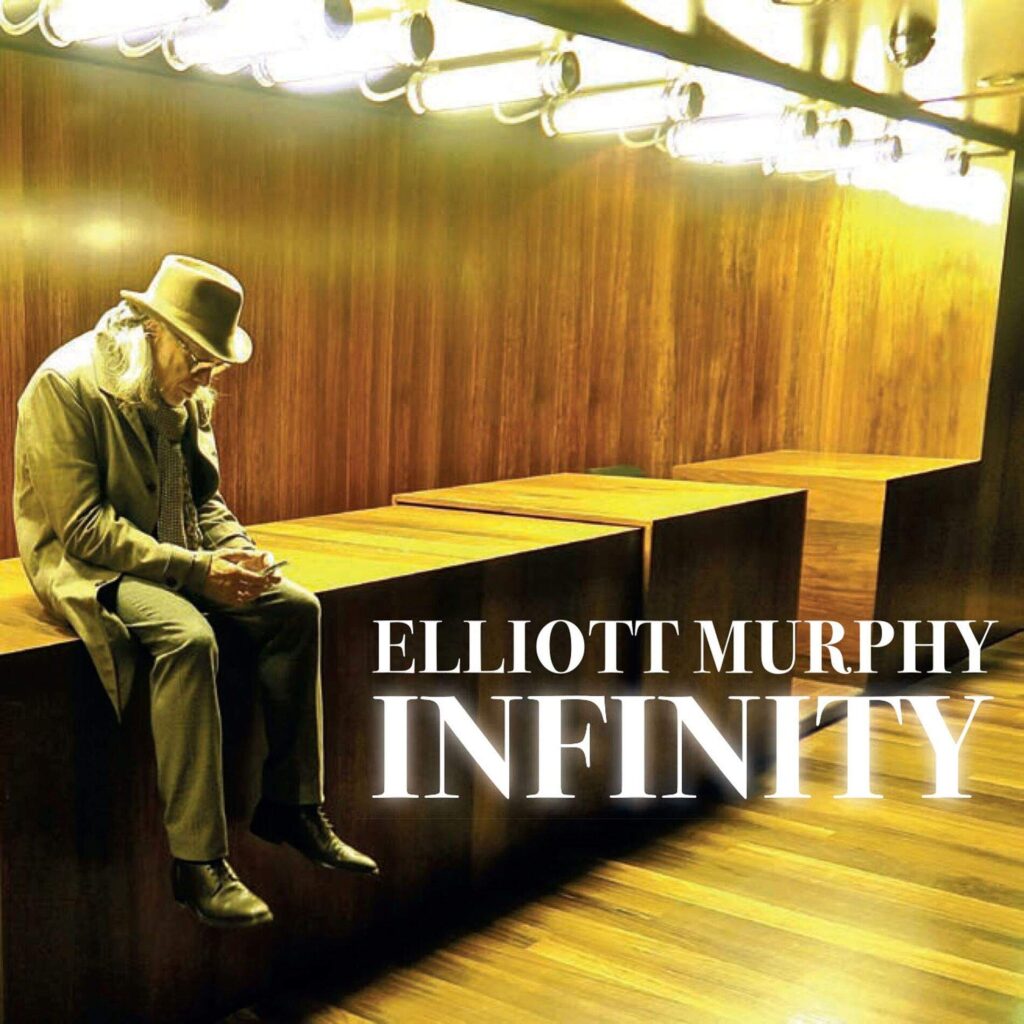

At nearly 75, he remains a restless seeker, forever chasing the next melody that will capture a moment in time. His latest album, ‘Infinity,’ is both a reflection and a fresh beginning, embodying a man who embraces the passing years without surrendering to their weight. With a voice seasoned by decades and lyrics that balance melancholy and hope, Murphy writes not just for his generation but for anyone willing to listen closely.

His relationship with music is intimate and unhurried. Songs come to him on their own schedule, almost as if they have lives independent of their creator. Working with his son Gaspard as producer adds a contemporary spark, yet the heart of Elliott’s work beats to timeless rhythms. Paris has been his muse for 35 years, a city that feeds his poetic sensibility and nurtures his restless spirit.

More than a rock and roll survivor, Murphy is a sage navigating the ever-changing landscape of creativity. He is proof that true artistry does not age. It deepens, it expands, and like the title Infinity suggests, it goes on and on.

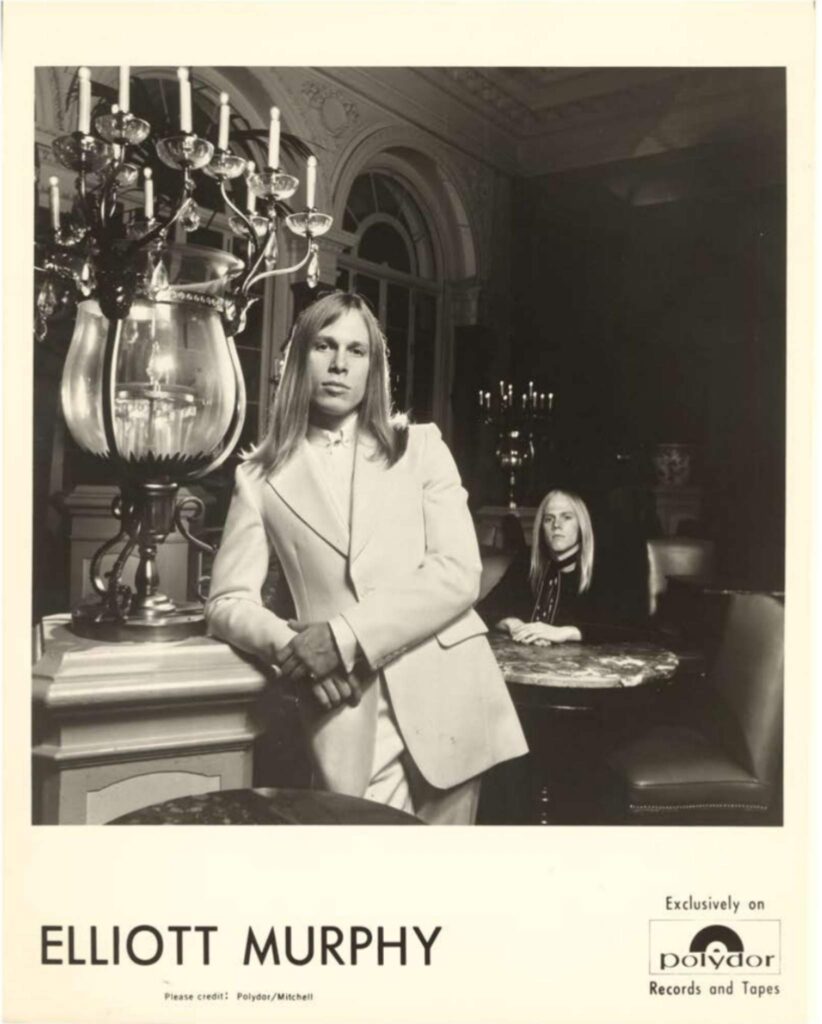

Originally his journey began in the suburbs of Long Island, where his early passion for music led him to form The Rapscallions, a teenage band that won the New York State Battle of the Bands in 1966. A brush with cinema came when he appeared in Fellini’s Roma, but it was back in New York where his path truly took shape. With his 1973 debut ‘Aquashow,’ he was hailed as one of rock’s new poetic voices. Albums like ‘Lost Generation’ and ‘Night Lights’ soon followed, affirming his place in the singer-songwriter pantheon.

“The songs know more about me than I know about the songs.”

‘Infinity’ feels like a continuation of your long journey through music, but also like a new beginning. Was there a specific moment or inspiration last year when the songs started coming together? How did the energy of the album take shape for you personally?

Elliott Murphy: In fact, every album of new songs I’ve ever released always feels like a new beginning because when it’s done, I’m already thinking about the next album to come as part of that new era. As we were doing the last mixes of ‘Infinity,’ my son and producer Gaspard Murphy turned to me and said, “Dad, next time we should make a very acoustic album …” so of course that got me thinking about writing songs that would work in an acoustic setting and that night I wrote a new song with that in mind. So it’s very important that every album should serve as an inspiration to me to start thinking about the next album. But getting back to ‘Infinity,’ I think the unique cohesive element of this album is that all the songs were written during a very short period – this last year – and then recorded soon after. ‘Infinity’ is an album that is not bound by any style and that was my original intention when I presented them to Gaspard but I did want the lyrics to work in an ensemble setting. For instance, ‘Makin’ it Real’ is an all-out up-tempo rocker that I played on my 1961 Fender Stratocaster (same guitar I played on ‘Aquashow’) while ‘Night Surfing’ is a very reflective ballad written on a ukulele. And yet those two songs connect in a way. Every album is a kind of personal memoir, when my style is frozen in time and ‘Infinity’ catches me both musically and lyrically as I am in my mid-70s. Rock ‘n roll should not just be left to the young. It’s too important for that.

You’ve said that your albums are like novels, with each song a chapter. If ‘Infinity’ is a novel, what would the theme or the central message be? What story do you hope listeners take away from it?

I’d like to say the overall theme of ‘Infinity’ is acceptance if that makes sense to you. The chorus of ‘Night Surfing’ repeats over and over, And there ain’t nothing you can do anyhow, and that sums up much of my wisdom if I have any at all. At my age, unlike Jay Gatsby, my fictional hero, I understand I can’t change the past, nor who I am but my hopes and dreams still live on in my heart and soul just like when I was a teenager. For each album, my hope is that it will reach a larger audience than the one before and I dream of playing larger venues. But I don’t want to be a rock celebrity for that is a full-time job spent mining for fool’s gold, which is to say it may glitter and shine but its value is meaningless. The story I hope that listeners will come away with after listening to ‘Infinity’ is that wisdom is precious, often unobtainable and when you do own a small part, it comes at a high price. And the music goes on and on and on … infinity.

How did working with your son Gaspard as the producer change the dynamic in the studio compared to your previous records? Was there a particular moment where his perspective as a producer influenced the direction of the album?

Well, first of all, Gaspard is a very busy producer and mixer with his own projects so my biggest challenge was to find time when we both were free and during those sessions try to work as efficiently as possible. These days I work very quickly in the studio and Gaspard too. Early on, it becomes apparent what each song needs and the elements necessary to achieve that result. I’ve got a great cast of musicians I work with now: Olivier Durand on any stringed instrument you could imagine, Melissa Cox on violin and beautiful backing harmony singing and Alan Fatras who has become a master of the Cajon and other percussive instruments. And they work fast too. At some point the nine songs that ended up on ‘Infinity’ stood out so a few others were left behind. And once we knew that, Gaspard took over and added production value to each song and also helped me pick out the best vocal takes.

Over the years, you’ve become a Parisian mainstay. ‘Red Moon Over Paris’ instantly caught my ear. Does the city still inspire you the way it did when you first moved there? How does Paris shape the music you create now compared to the early days?

Paris, “the city of light,” is my spiritual home in a way that New York never was. I’ve lived here for 35 years in the same apartment and that’s just amazing! You see, I’m an expatriate, and we are more at home when we’re not at home and that defines me perfectly. Aesthetically, Paris is a true marvel, and the beauty of the city still overwhelms me after all these years. But it’s hard for me to say whether one geographic location or another shapes my music or not because mostly I live inside my own reality which can be quite different from what’s going on around me. My musical roots were planted a long time ago in America and I’m grateful to have grown up in a golden age where you heard Motown, folk, English rock and everything else on the radio. I suppose that’s still where my melodies and chord changes come from. But lyrically it’s another story and Paris is a city that admires poets. I hope that an Elliott Murphy song could be quickly identified as such for better or worse.

You’ve been performing and recording for decades now, but with each album, there’s always something fresh. What’s the key to staying creatively invigorated and avoiding the pitfalls of repetition?

The key for me is to perform enough shows each year that musically I stay fresh. I’m still able to coax new songs out of my guitar in hotel rooms. But at the same time, it’s important to me to not do too many shows so that it becomes a repetitive exercise, and you start singing the songs without feeling the words resonate in your memory. That never happens because I don’t let it happen. I refuse to let my career become plain work. When it comes to writing, I’ve never tried to repeat the success of a certain song with a similar new one. I wouldn’t know how.

‘Baby Boomers Lament’ touches on generational themes. As someone who has lived through so many cultural shifts, do you think there’s a distinct ‘sound’ to each generation? How do you find the balance between writing for your own generation while staying relevant for newer ones?

Does my music really belong to a certain generation? I don’t think so. To be true to yourself and avoid the current fads in style is the most important element in lasting art from generation to generation and that goes for painters, writers as well as singer-songwriters. Why do certain novels stay relevant, but others are as dated as a horse and buggy? I can read Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn today as easily as I can read Jack Kerouac and I can listen to Billie Holiday or Amy Winehouse and feel no sense of generational gap. But I’m subjected to the same news and cultural overload of information as everybody else. It’s almost impossible to isolate yourself from it, and this is the challenge for any artist today. During my shows I ask how many baby boomers are in the crowd, how many millennials, how many generation X, Y, and Z, and thankfully there are always representatives from all of these generations. So I must be doing something universal without even knowing it. There’s a song on ‘Infinity,’ ‘Baby Boomer’s Lament,’ which everyone can relate to when I sing, “This world is run by maniacs, at least that’s what John Lennon believed.” You don’t have to be a baby boomer to know that’s sadly true, do you?

You’ve always been known for your poetic lyrics. Was there any specific influence or source of inspiration that drove the lyrical direction of this album? And I’m curious—how do you know when a lyric is “right”?

Once upon a time there were many singer-songwriters known for their poetic lyrics, all the way from Eric Andersen to Warren Zevon, and if you didn’t have some poetry in your musical baggage then you didn’t carry the necessary bona fides. My generation of rock songwriters was clearly inspired by poets such as Allen Ginsberg and Arthur Rimbaud and when Bob Dylan kicked the door open with lyrics that were not only poetic but commercial as well, you had to pay attention because your song might be heard on the radio and reach a large audience. I remember clearly the first time I heard ‘Last of the Rock Stars’ from ‘Aquashow’ on the radio in New York. That was the moment in time when it all became real for me. Songwriters are different from pure poets or novelists because without the music the lyrics appear dead on the page. It’s the sublime melodies and catchy chord changes and pulsating rhythms that give the words wings to fly on – that’s where the magic lives – and it’s easy to feel when that magic is happening. When the chorus of ‘The Lion in Winter’ comes in, I feel that magic every time.

Your debut album, ‘Aquashow,’ still resonates with so many people. Looking back at the early days of your career, how do you view that moment now? Is there a specific part of that period you look back on with pride or even fondness?

Speaking as the youthful Elliott Murphy, the wannabe rock star, he can look back at the early days of his career with regret and missed opportunities. So many business mistakes and not enough time on the road learning my craft and being led by my ego and not by my soul. But speaking as Elliott Murphy the recording artist in his mid 70s, I’m so grateful for the songs I was able to write during those very difficult times and the albums that came out of it. My life changed overnight from a complete unknown (just like the title of the Dylan film) to having my photo in major magazines all over the world. But those songs came from a place pure and incorruptible and were really the solid footing that enabled me to have a career that keeps going after more than fifty years. I think of the Bob Dylan line, I was so much older then I’m younger than that now … and at 76 with the release of ‘Infinity,’ I do feel younger than I did at 24 when ‘Aquashow’ came out and my life changed irreversibly.

You’ve played with some incredible musicians over the years, but your long-standing collaboration with Olivier Durand is something special. What makes that partnership so enduring? How has your creative relationship evolved over the years?

Olivier Durand has been my musical partner for over 29 years and there are a lot of reasons we’ve been able to do that. We’ve been together longer than John Lennon and Paul McCartney! And the reasons for that? Well, I’m not the easiest person to always get along with and when I’m down or frustrated Olivier knows how to give me space. And he is really a virtuoso guitarist and together we find the perfect way for his guitar to work with my songs and bring them to a higher level. Olivier goes over the set minutes before each show and if I forget a line to a song on stage, I can turn to him and he will prompt me. I’m nearly 20 years older than Olivier but our musical roots are very similar … although he knows more AC/DC songs than me!

The album is called ‘Infinity,’ and that feels like a perfect title for someone who’s been in the game for so long and keeps evolving. How do you think about time in relation to your music? Is there an ongoing evolution you see in your work, or do you feel like you’re in a constant state of rediscovery?

As the Rolling Stones sang, time waits for no one, and that is surely true. But what is time anyway? Scientists cannot discover what the appeal of music is. Is it the rhythm or the melody? And unlike other art forms, you can’t see music, you can only hear it. I have a song “On Elvis Presley’s Birthday” that I sing at every show and often the audience does not have English as its first language and still the reaction is always explosive. How do you explain that? As for me, is it a constant state of rediscovery or anxiety? Probably a little of both if I’m being honest. Do I have 24 years left? Will I make it to 100? I hope so but I’m trying to become immortal with my music. And why not?

There’s always been this wonderful tension in your music between joy and melancholy, lightness and depth. Is that something you consciously strive for, or is it a byproduct of your writing process?

I think that tension between “joy and melancholy, lightness and depth” is a good definition of how I get through life. Music has always been and still is a way for poor me to discern my place in this world. When I start to write a song, I begin with a few words and then a few chords and soon it has a life of its own. The songs know more about me than I know about the songs. I never consciously strive for anything in a song but I do try and make my songs cohesive and edit the lyrics to best ride along with the music. There’s a lot of craft involved in writing songs, it’s not just pure inspiration, and I enjoy both parts. If someone was to ask me about my “writing process” (as you just did), I would have to say there is no process. The songs come out of my guitar or piano at their own speed. I’m just there to catch them when they do.

‘The Lion in Winter’ and ‘The End of the Game’ suggest a certain reflection on the passage of time. Do these songs represent an older, wiser version of you, or are they more about the world around you?

‘The Lion in Winter’ is perhaps my personal favorite on ‘Infinity’. It’s dedicated to my friend Peter Beard who passed away last year and was a charismatic and truly unique character. Fearless which is something I am not. Peter lived in Africa for much of his life and that became the metaphor for the song: an old lion lying on the Serengeti Plains waiting for one more kill and not ready to stop roaring. That’s me.

You’ve touched on the idea that “Infinity” deals with our current confusing times. Do you find it harder to write about the world today, or has it opened new channels for creativity? How do you navigate the balance between the personal and the universal in your songs?

The zeitgeist of the world we live in is always difficult to put into a song or even literature. And these days, with things changing so rapidly, change occurs at an even faster pace than ever. The speed of recording has revved up as well. Back in the 70s we would spend hours in the recording studio just perfecting a good drum sound but today with the help of programs like Pro Tools or Logic Pro it takes only minutes to achieve the same result. Some wise men say there is no difference between the personal and the universal but of all the news I’ve watched on TV—besides the weather report—I must ask myself how much of it has actually affected my personal life? Not much really. And yet, like everybody, I still am affected by everything that’s going on around me mentally, physically and spiritually. But today the sun is shining in Paris and I better get out and enjoy it because no matter what the world does this day is not coming back. And I’ll probably pick up a guitar and do some vocal exercises and get to the gym too.

Lastly, after 52 albums, do you still get nervous about a release? How do you measure success these days—by the sound of the album, the response from fans, or something else entirely?

Sometimes I measure success by the amount of plays ‘Infinity’ is getting on Spotify and I’m grateful to say this album seems to be working well. But when I finally have the finished album in my hand on CD or vinyl that’s when I feel truly successful. I’m old school. Let’s say I still get nervously hopeful with the release of each new album. I don’t want to be too optimistic and set myself up for disappointment but at the same time I have to be able to express my belief in my work (as I’m doing now in this interview) if I want others to hook on to that belief and get interested in what I’m releasing. Sadly, these days albums have a short “shelf life” and in a month they are usually forgotten no matter who the artist is. I’ve written about 500 songs and released over 50 albums and yet each night when I’m about to give a concert I prepare a set list of maybe 25 songs which is about five percent of all the songs I’ve written. And it’s very difficult to leave songs behind. Maybe artificial intelligence will show me how to deal with that imbalance in the future.

Klemen Breznikar

Elliott Murphy Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / YouTube