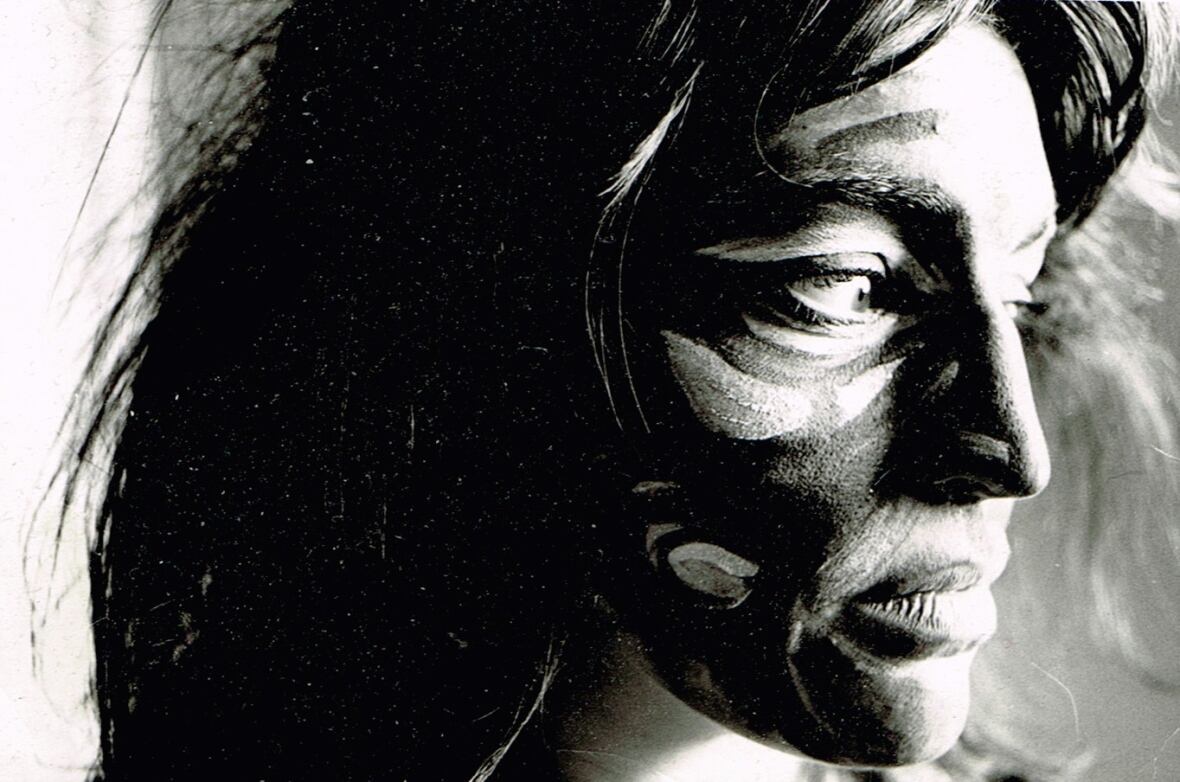

Erica Pomerance: A Nomadic Songline Through the Avant-Garde and Beyond

Erica Pomerance exists at the rare nexus where the earnest idealism of the 1960s folk revival converges with the outer reaches of avant-garde improvisation, before unfurling into a profound commitment to global social justice.

Her sole, enigmatic 1969 album on ESP-Disk, You Used to Think, remains a cult artifact – a whispered secret among collectors, yet only a single, kaleidoscopic facet of a life lived with unwavering intellectual curiosity and a restless, humanist spirit. Like the shifting sands of the Magdalen Islands or the vibrant indigo textiles of Mali that now occupy her, Pomerance’s journey is a rich tapestry woven from music, film, activism, and an enduring quest for understanding.

Born and raised in Montreal, Pomerance’s early life was steeped in a milieu of left-wing values and artistic encouragement. Her parents, Canadian-born children of Jewish immigrants from Ukraine and Romania, instilled in her a deep humanism and a love for the arts. Memories from her childhood are vivid, almost cinematic: sitting on Paul Robeson’s lap during his Montreal visit, attending a leftist summer camp at nine where she encountered folk and blues luminaries like Pete Seeger, Sonny Terry, and Brownie McGee. This early exposure to American folk and blues, alongside her parents’ eclectic record collection that spanned classical, Broadway musicals, and the burgeoning folk scene, laid the groundwork for her musical sensibilities. She embraced piano, guitar, drama, and dance, but it was writing—poetry, plays, fiction—that initially captivated her, leading her to believe her path lay in journalism. The folk-blues of Joan Baez, whom she met and corresponded with in the early 60s, became an early obsession, a vocal lodestar.

Montreal in the 1960s was a hotbed of cultural ferment, a pivotal backdrop to Pomerance’s artistic awakening. She immersed herself in the McGill Folk Society, the city’s vibrant folk clubs, and coffee houses like the Fifth Amendment and The New Penelope, where she witnessed legendary acts like The Mothers of Invention and Howlin’ Wolf. It was here she crossed paths with Leonard Cohen, then primarily known as a poet, leaving a lasting impression. A brief romance with blues scion John Hammond Jr. further connected her to the burgeoning scene.

Pomerance’s path soon veered into filmmaking. While studying English Literature at McGill, her interest in cinema blossomed. A summer workshop at the National Film Board of Canada led to work on documentaries and a stint with Quebecois production company Les Films Claude Fournier. By 1967, she was directing her own half-hour documentaries for Canadian and French public television, honing a visual storytelling craft that would define much of her later career.

But the siren call of music, and a broader cultural awakening, proved irresistible. In early 1968, finding herself in Paris, Pomerance was swept up in the electrifying currents of the May ’68 revolution. She busked on the streets, slept in the Sorbonne, and witnessed firsthand the radical political and artistic occupations. This period ignited a profound political consciousness, inspiring songs like “La Révolution Française” and “Julius,” written for an African American boyfriend imprisoned for dealing hash in Paris.

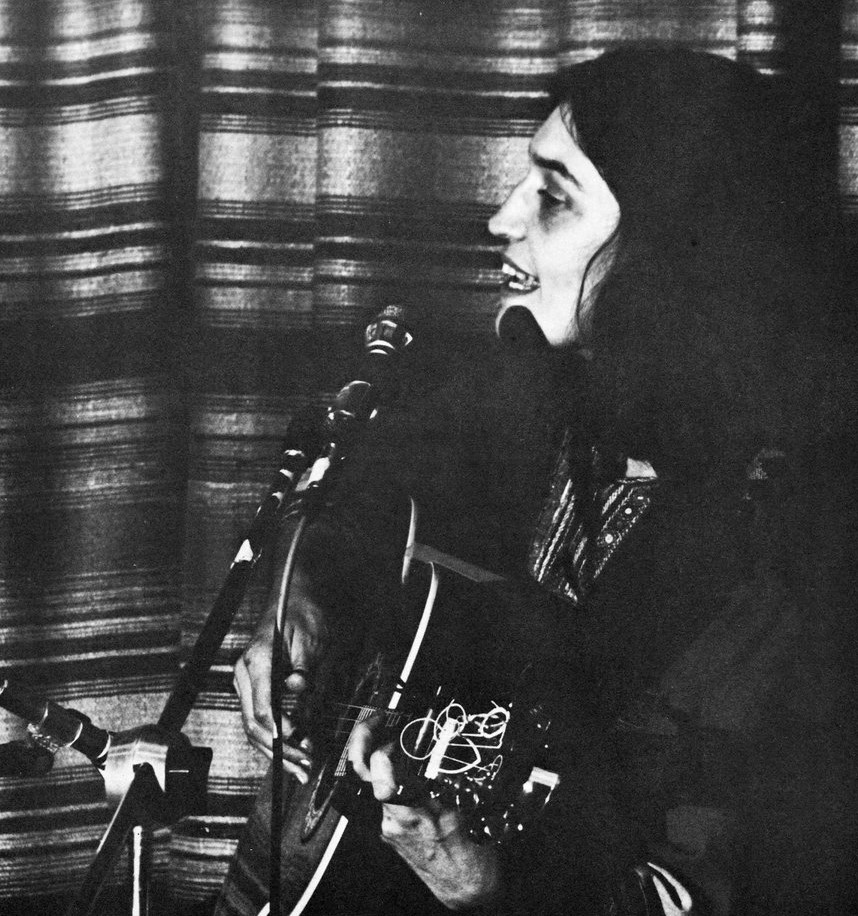

Upon her return to North America in June 1968, the currents of the counterculture pulled her towards New York, where she met Richie Heisler, a key figure in the creation of You Used to Think. Her connection with ESP-Disk came organically: she took a job in Bernard Stollman’s office, and he, recognizing her unique talent, offered her a recording deal. The album itself, a singular document of psychedelic folk-jazz, was primarily captured during a snowstorm-laden second session, an improvised, acid-fueled burst of creativity. Pomerance vividly recalls the spontaneous nature of the recording, high on LSD, with musicians like Richie Heisler (guitar), Gail Pollard (sitar, flute and chanting), Trevor Kholer (alto sax), Ron Price (bass), and Tom Moore (drums) joining her. The resulting mix, a “preemptory mix/mastering” due to budget constraints, lent the album its raw, ethereal quality.

You Used to Think defies easy categorization. Tracks like “We Came Via” feature an almost Middle Eastern modality, largely influenced by Richie Heisler’s intricate guitar work, while the album’s overall vibe reflects Pomerance’s immersion in meditation and yoga, a search for deeper consciousness beyond overthinking and intellectualization. The lyrical tapestry weaves in philosophical ponderings and personal experiences, colored by the psychoactive landscape of the time, as evidenced by her poem “Frescoherence on the Sinistrene Chapel.” Her awareness of ESP-Disk’s avant-garde roster, from The Fugs to Marion Brown and Pearls Before Swine, placed her firmly within a lineage of outsider artists.

The album’s release in early 1969 coincided with a period of intense wanderlust for Pomerance. She journeyed to an ashram on Paradise Island in the Bahamas, teaching asanas, before heading west to San Francisco. Here, she experienced the tail end of the Haight-Ashbury era, living near Jefferson Airplane, frequenting Bill Graham’s concerts, and even a brief, surreal stint as a dancer in a Chinatown club. Her restless spirit then led her south to Mexico in an old GM truck, renting a wooden house near Petatlán, exploring the mountains of Oaxaca, and experimenting with magic mushrooms. This idyllic, if precarious, existence was shattered by Nixon’s War on Drugs, leading to a dramatic round-up of hippies by the Mexican army and her forced return to San Francisco.

By the fall of 1970, Pomerance was back in Montreal, where she landed the role of Jeannie, the second female lead, in the city’s bilingual production of the musical Hair. This period was marked by the Canadian War Measures Act and the FLQ crisis, which saw Montreal under military surveillance. Her personal brush with the era’s tensions came when she and cast members, including Robert Villefranche (who played Hud), were arrested, mistaken for Black Panthers due to a prop pistol.

In the decades that followed, Pomerance seamlessly integrated her artistic and activist impulses. While continuing her musical pursuits, she delved deeply into documentary filmmaking, becoming a central figure in Montreal’s documentary community. She worked with the National Film Board of Canada, Télé-Québec, and became a founding member of RIDM (Les Rencontres Internationales Documentaire de Montréal), actively fostering connections between Francophone and Anglophone documentary communities. Her films consistently championed social justice, addressing critical issues from women’s rights and reproductive health to cultural diversity, environmental concerns, and First Nations rights. Her extensive filmography includes impactful titles like Dabla Excision, Operation Survival, Tabala, Rhythms in the Wind, and more recently, After the Coup: Malian Women Speak and Migrants of the Dunes. Her work has extended to West Africa, particularly Mali, where she has been a part-time resident since 2000. Here, she champions the traditional indigo textile craft of the Dogon people and advocates for improved maternal health. She continues to direct, film, and edit, providing translation, subtitling, and video workshops for emerging African artists and filmmakers.

Despite the profound impact of her filmmaking career, music remains a vital current in Pomerance’s life. In 2018, the previously unreleased 1972 live recording En Concert À La Commune Le P’tit Québec Libre saw the light of day via Tour de Bras, featuring her alongside members of Jazz Libre du Québec. This discovery, from the archives of Jazz Libre du Québec, was a revelation, shedding new light on her post-ESP musical evolution and rekindling her desire to perform. She hints at a trove of unreleased material, particularly French songs like “Nahani,” “Rossignol,” and “Pêcher aux Îles de la Madeleine” – songs she holds most dear, alongside the English “The Slippery Morning.”

Erica Pomerance’s nomadic existence, spanning Montreal, New York, Paris, the Bahamas, San Francisco, Mexico, and Mali, has enriched her perspective, allowing her to bridge cultural divides and connect with people across continents. From sitting on Paul Robeson’s lap to participating in May ’68, from her singular psychedelic folk album to her pioneering documentary work in Africa, Pomerance’s story is a compelling counter-narrative to the fleeting celebrity of the counterculture. It is a story of enduring commitment to humanist values, artistic integrity, and a fierce, unwavering hope for a more just and equitable world for future generations.

The following is an exclusive interview with Erica Pomerance, where she shares insights into her world of art.

It seems your early love for music stems from folk and blues records. What were some of the most significant albums from that time, and what was the local music scene like? Were there plenty of places to buy records and enjoy live music?

Erica Pomerance: Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, Judy Collins, The Weavers, New Lost City Ramblers, John Hammond, Reverend Gary Davis, Chuck Berry, Joni Mitchell, John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, and French-language artists like Léo Ferré, Jacques Brel, Édith Piaf, Georges Brassens, and Renaud. Also, Québec singer-songwriters such as Gilles Vigneault, Claude Gauthier, Monique Leyrac, Louise Forestier, Robert Charlebois, and Pauline Julien; groups like Harmonium, Les Séguin, Beaux Dommages, and Jazz Libre du Québec (some of the latter are my contemporaries); and of course, the McGarrigle Sisters.

At what point did you realize that a career in the arts was your true calling?

Erica Pomerance: At just nine years old, I wrote my first short story, which my father had printed. In my twenties, I even began writing a couple of novels based on my life experiences. Back then, I thought I’d become a writer or journalist.

I was also very interested in film during university—I was a member of the McGill Film Society and was eventually invited to participate in a summer workshop at the National Film Board of Canada. There, I worked on my friend Tanya’s seminal documentary The Things I Cannot Change and co-wrote a feature script (never produced) with Mike Robbo, who was a director at the NFB at the time.

I was accepted into the LA Film School, but before I could attend, I was hired by the Quebecois production company Les Films Claude Fournier in 1967. There, I learned to record sound, edit 16mm film (on a Moviola), and directed three half-hour documentaries for Canadian and French public television.

How did you first meet Leonard Cohen, and what was your impression of him back then? Can you share more about that period and how he influenced your creative journey? Could you describe the atmosphere of the folk clubs you frequented? What were some of your most memorable performances in those venues?

With my friend Wendy, I took trips to New York where we went to places like the Folk Dance House and met interesting friends from the New York folk scene. I was attending McGill University as an English Lit major and played in a duo with my friend Fran Liberman (now Fran Avni, an accomplished musician and producer with the Jewish Renewal movement in the U.S.).

At McGill, I acted in university musical productions and was president of the McGill Folk Society for one year. Members included Kate and Anna McGarrigle, who taught us madrigals. We all hung out at folk clubs that featured artists like The Mothers of Invention, Bob Dylan, and various blues legends such as Reverend Gary Davis and Howlin’ Wolf. I was kind of a folk and blues groupie.

A close friend of mine, folk musician Gary Eisenkraft, opened a series of coffee houses over the years that featured both legendary folk and blues artists as well as local talents. At one point, Gary took over a venue on Bleury Street called the Fifth Dimension and renamed it the Fifth Amendment. It was there that I first met Leonard Cohen. He wasn’t performing publicly at the time…he had come to hear a blues artist, perhaps Reverend Gary Davis.

Leonard and I saw each other off and on over the next couple of years. He would return to his old Montreal haunts and visit the McGill campus, where he had many admirers. Back then, he was still known primarily as a poet and novelist—he had already published The Favourite Game.

Gary Eisenkraft’s final Montreal club was The New Penelope on Sherbrooke Street, right next to the Swiss Hut, where hippies and folkies would congregate before or after shows to drink beer, since there was no alcohol served in the folk venues in those days. I remember hearing Elvin Bishop and The Mothers of Invention there, and I actually got to meet Frank Zappa! I also had a fleeting romance with John Hammond Jr., who was in town for a performance—possibly at one of Gary’s earlier clubs. He’s a musician I admire immensely.

What motivated you to travel to Europe, and how did the May ’68 social revolution influence your music and songwriting, particularly regarding songs like “La Révolution Française”?

After the funding from Expro dried up, the small francophone production company I was working with let me go, and I returned to performing. I rented a huge house in Old Montreal—which at the time had not yet undergone the upscale renovations that characterize it today. I lived there with a bunch of hippies, including Jesse Winchester, who had come to Canada as a draft dodger to avoid being conscripted for the Vietnam War.

The ground floor served as a studio for Terry Mosher, now the renowned Canadian political cartoonist Aislin.

Unfortunately, the house got a bad reputation when mafia-linked drug dealers began visiting one of the residents, and we eventually had to terminate the lease.

In early 1968, I spent a few months in France, where my brother was studying cello at the Conservatoire. I started busking outside cafés on the streets of Paris and soon became involved in the May ’68 social and cultural revolution. I lived for several days with political artists, anarchists, and students who were occupying the Odéon Theatre and the Sorbonne.

I remember sleeping on a cot in the university stacks, which had been transformed into a kitchen and infirmary to support the occupiers and provide first aid to the Amazones—a corps of female protestors who took to the streets at night, throwing cobblestones at the police, and often returned suffering from tear gas exposure.

That period inspired my song “La Révolution Française” and marked the beginning of my bilingual songwriting in French and English. The song Julius was written for an African American boyfriend I had in Paris who was arrested for dealing hashish. I managed to get permission to visit him in prison by pretending to be his sister. I wore dark lipstick and claimed to be a light-skinned mulatta to convince the judicial clerk, who was hidden behind a stack of files in a musty prison office. In those days, no one was yet particularly concerned about cultural appropriation.

Can you share the story behind the recording process for You Used to Think? What challenges did you face, and what made that session stand out? How did your collaborations with Richie Heisler and other musicians shape the final outcome of the album? What impact did he have on the recording?

In June ’68, I returned to North America. Not exactly in good graces with my family in Montreal, I reconnected with my old friend Richie Heisler in New York. We rented a cockroach-infested room in the Village, and I started attending open mic nights at local coffeehouses.

One night—I think it was at Gerde’s or The Gaslight—I sang and met Bernard Stollman, head of the ESP-Disk label. Bernard offered me a job cataloguing records at the ESP office and eventually proposed that I record an LP of my own material.

The second recording session, a single live take, is what ultimately made it onto the album. It was a bit wild—the night we recorded, we were all high on acid and arrived late to the studio during a huge snowstorm. The entire city of New York was paralyzed. We set up and began playing, improvising many of the pieces as the night went on. The mix and mastering were rushed, as ESP was strapped for cash and certainly didn’t have much of a budget for unknown newcomers like me.

A key influence on my musical style at the time—and on the album’s sound—was Richie Heisler (now known as playwright and singer-songwriter Richard West), who performed on the record along with Gail Pollard on sitar, flute and chanting, Trevor Kholer on alto sax, and Ron Price and Tom Moore. Before “world music” became a recognized category, we had developed a Middle Eastern sound on songs like “We Came Via.” That particular song turned out to be oddly prophetic, as many years later I began spending significant time in West Africa, where I’ve made numerous documentaries and have been deeply involved in the local film community and in initiatives to preserve and promote traditional craft textiles.

At the time, under Richie’s influence, I got into meditation and yoga. The central theme of You Used to Think was born from the idea that in Western society, we’re conditioned to constantly overthink, intellectualize, and analyze every concept. Instead, the album suggests embracing a more intuitive approach—going with the flow, transcending external images, and learning to fully integrate and understand our life experiences.

Did psychoactive substances influence the music you created for the album? Would love to hear about acid visions you had…

I once wrote a poem on acid entitled Frescoherence on the Sinistrene Chapel, which was published in a McGill University anthology.

Were you familiar with other ESP artists, such as The Fugs, The Holy Modal Rounders, Seventh Sons, Randy Burns, The Godz, Octopus, Pearls Before Swine, or Cromagnon?

Primarily, I was familiar with Tuli Kupferberg and The Fugs, as well as members of Pearls Before Swine and saxophonist Marion Brown, whom I’d previously hung out with in Paris. I was aware of the others and likely encountered several of them at the ESP offices, but I didn’t get to know them personally.

I first heard about ESP through my friends Tanya Ballantyne Tree and Bruce McKay, two Montreal filmmakers who also recorded an album with the label in the ’60s. I stayed in touch with Bernard Stollman and once visited his place in Woodstock, where he had a studio. Over the years we connected by phone and email, especially when he licensed some ESP releases to European distributors in the ’90s.

You Used to Think was reissued on CD by first a German label and then an Italian one in the ’90s, but no royalties ever materialized. All the songs were originally registered with BMI, then ASCAP, and also with SOCAN, the Canadian music rights society. But it was a common story among ESP artists: royalties were practically nonexistent. In all the years since I recorded You Used to Think, I’ve never received a single cent, even though the record has now become something of a collector’s item…

Can you discuss the insight behind some of the songs on the album?

“Burn Baby Burn” is based on lyrics by Lee Bridges, an African American poet friend who was living in Paris while I was there. It has civil rights overtones and reflects the rage and struggles of Black people living in America. “The Slippery Morning” is my own reflection on identity and racism. The lyrics still resonate with me today, and I continue to perform it. “Koanisphere” was totally improvised—I was into making up lyrics spontaneously at the time, especially when singing outside street cafés. The vocal contributions by Richie and Gail reflect our attraction to Eastern spirituality, which was becoming a trademark of the hippie generation in the ’60s. “To Leonard From the Hospital” was dedicated to Leonard Cohen, written from a maternity ward in a Paris hospital after complications from an illegal abortion.

You performed in the Montreal production of Hair. What was that experience like?

After we recorded the album, Richie, Gail, Richie’s young girlfriend Janet, and I went to an ashram on Paradise Island in the Bahamas, where we taught asanas to older people in search of spiritual enlightenment. The ESP album was released while we were there, in early 1969. It received a surprisingly great review in Vogue magazine, comparing me to Lotte Lenya, the avant-garde German artist.

We eventually fell out with Swami Vishnu at the ashram and left for San Francisco, where we rented an inexpensive apartment—something still possible in those days—on the same street as Jefferson Airplane. It was the time of Woodstock in New York, but things were also happening on the West Coast. We hung out in Golden Gate Park, playing music and attending concerts promoted by Bill Graham, who was just emerging as the king of the psychedelic rock scene. I recall one concert we heard about that turned violent after being infiltrated by the Hells Angels—I think someone may have even died.

At one point, I did a very short stint as a dancer in a seedy club in San Francisco’s Chinatown, but after a few nights, I realized it wasn’t for me. We then headed to Mexico in an old GM truck and stayed for a few months. We rented a wooden frame house with no window screens on a beach near Petatlán. The landlord was a former soldier who grew marijuana and corn. One day, while on the beach, we were pressured to leave Guerrero by a local politician who didn’t like hippies.

In the mountains of Oaxaca, we took magic mushrooms, following in the footsteps of Donovan and the Beatles, who had been there and written songs about it (“First There Is a Mountain,” “The Fool on the Hill”). As we meditated on nothingness, attempting to reach the bardo states described in the Tibetan Book of the Dead, hippies were being rounded up and arrested by the Mexican army—a campaign financed by Nixon as part of his War on Drugs. The fields of Acapulco Gold were all being set on fire at the time.

Our motley crew was eventually sent back to San Francisco, and I later returned to Montreal. In the fall of 1970, I landed the second female lead as Jeannie in the Montreal production of HAIR (“Hello sulfur dioxide, hello carbon monoxide. The air, the air is everywhere…”).

Those were complicated times in Québec. While we performed the musical nightly in French and English at the Comédie Canadienne theatre, the city was under military surveillance due to the imposition of the Canadian War Measures Act. This followed the FLQ (Front de libération du Québec)’s assassination of a prominent politician during the height of the separatist movement.

One night, a group of our cast was arrested in a red Volkswagen because Robert Villefranche, who played Hud, had a prop pistol on him. The police mistook him for a member of the Black Panthers. I spent two hours in a holding cell with a few local sex workers before our production manager, Linda Hassler, got us released after a few well-placed phone calls.

How did you transition into documentary filmmaking? What titles have you worked on that we can look out for?

Since the 1960s, I’ve been involved in both music and documentary filmmaking. As mentioned above, I began at the National Film Board of Canada and later worked with a francophone production company in 1967. At the time, the emerging French-language film community was becoming a powerful creative force within the sovereignty movement, which helped shape today’s secular Québec society and cultural identity.

When I lived in the Îles de la Madeleine during the 1970s and ’80s, I returned to documentary filmmaking with the Télé-Québec network. After moving back to Montreal in the late 1980s, I became active in the city’s dynamic documentary community. I believe I’ve played a role in several associations that have helped shape broadcast and public support for documentary filmmaking. I was also a founding member of RIDM (Les Rencontres internationales du documentaire de Montréal), a major documentary film festival in Montreal.

I currently sit on the board of the Alter-Ciné Foundation, which supports documentary filmmakers in the Global South. I’ve also worked to strengthen connections between the francophone and anglophone documentary communities in Québec and Canada, and have served on numerous boards and film production think tanks in that capacity.

My films include Dabla Excision, Operation Survival, Tabala, Rhythms in the Wind, The Pact, After the Coup: Malian Women Speak, and Migrants of the Dunes. They can be found on the Taling Dialo Vimeo channel. Most are in French, though some have English-subtitled versions. I also do translation and subtitling work, and produce video demos for African performing artists in Québec. I frequently give video workshops for youth and emerging filmmakers in Québec and West Africa. I continue to direct, film, and edit my own documentaries.

There’s a recent live recording titled En Concert À La Commune Le P’tit Québec Libre. Can you tell us more about it?

The record company Tour de Bras approached me about releasing a 1972 live recording of my performance that they found among the archives of Jazz Libre du Québec. I agreed, and the limited vinyl edition has sold moderately well, attracting some media attention in Québec. That motivated me to start performing again, mainly on the Magdalen Islands, where I spend the summer months.

Is there any unreleased material that fans can look forward to? Which songs are you most proud of, and what was your most memorable performance?

I have quite a few songs in French that have not yet been recorded, or have only been recorded by other francophone artists. Hopefully, I’ll be able to record them myself someday soon. “Nahani” is one such song, a lullaby written for my daughter when she was a baby.

Another song I’m proud of is “Rossignol,” which expresses concerns shared by many First Nations and Indigenous peoples about the damage we’ve inflicted on the natural world and other species. Pêcher aux Îles de la Madeleine is my French translation of an English song that has become something of a local anthem in that Acadian community.

What else currently occupies your time and creative energy?

More film projects; collaborative efforts with my husband Mamoudou Nango—who is from the Dogon ethnic group and a member of the indigo dyeing clan—to promote traditional indigo textiles from Mali; work to improve maternal health in West Africa; singing and performing; reading, writing, swimming in the ocean, staying fit as I age; connecting with young people; and bridging cultural divides.

Reflecting on your journey, what stands out as a highlight?

My varied and nomadic life, and the enriching experiences with people I’ve met and worked with, both at home in Québec and in Africa. Also, witnessing the strange evolution of our world, which seems to be plunged into chaos again after so many efforts to free humanity from the cycles of exploitative tyranny that always seem to resurface in reaction to progress.

I try to see things from a more global perspective…as part of the eternal cosmos from which we’ve emerged…and hope that the struggles and efforts of so many will eventually bear fruit and have a positive impact on the lives of our children, grandchildren, and generations to come.

I have a wonderful daughter and three talented grandchildren now living in France, while my husband has four adult children and several grandchildren of his own in conflicted Mali. We continue to hope and strive to make things better for them, and for others like them.

Klemen Breznikar