Asgard: Rediscovering Coventry’s Lost Proto-Prog Treasure

Against all odds, another lost relic slips through the cracks of time — and we have Lee Dorrian and Rise Above Relics to thank for the rescue.

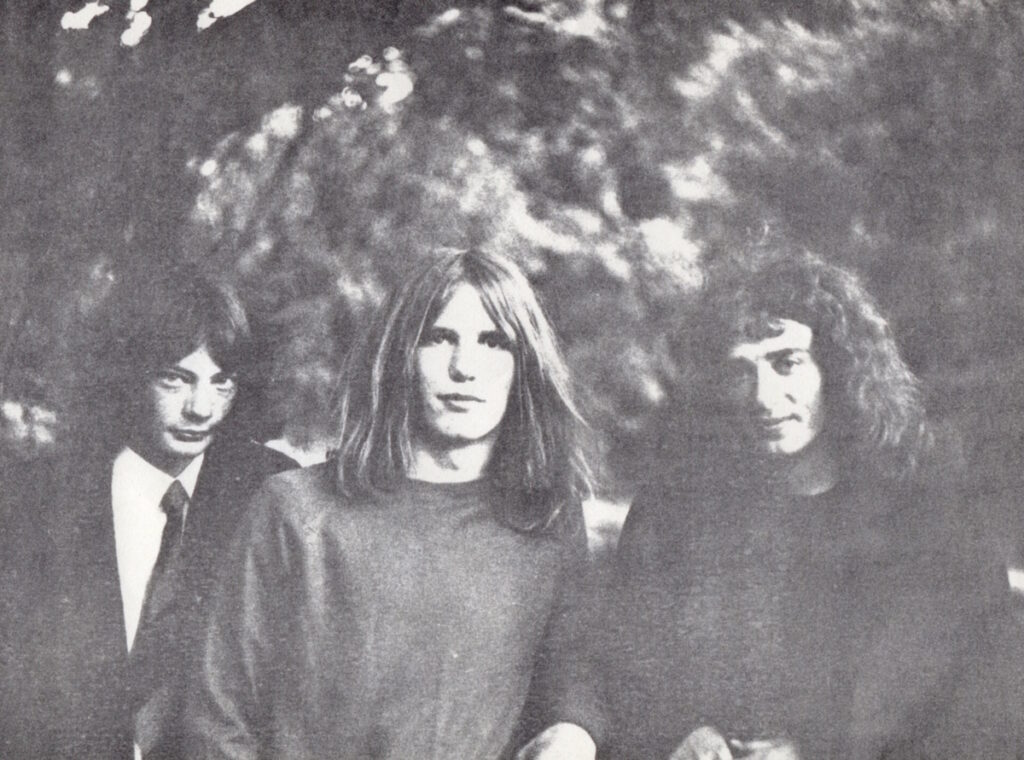

This is the story of Asgard, a proto-progressive trio from Coventry whose music was buried for decades on a battered, one-sided acetate. Until now. Thanks to Lee’s tireless devotion to the underground, these ghostly, long-forgotten tracks have been lovingly restored, pressed onto vinyl, and unleashed into the world once more.

Asgard were no ordinary band. Rooted in the twilight of the ‘60s psychedelic and progressive rock experiments, they drew from the sonic shadows of early Pink Floyd’s swirling textures and the cool monotone edge of The Velvet Underground. But their sound wasn’t a simple homage — it was a restless beast, shape-shifting and wandering deeper into the psychedelic unknown.

Honestly, it’s a mystery how these lost gems keep turning up. The acetate itself was more patchwork than vinyl — lacquer flaked and glued with care — yet Rise Above’s painstaking restoration breathes life back into these fragile grooves. What emerges is a snapshot of a moment, a historical document for anyone still chasing that heavy psych dream.

Listening to ‘Trivialities,’ ‘Month,’ and ‘Sunrise’ is like stepping into a smoky basement in 1970 Coventry, where the air is thick with experimentation. The Farfisa organ hums and swells, the guitar spins hypnotic patterns, and the rhythm section grounds everything with steady resolve. Moments of hushed introspection give way to sonic storms that linger in your mind long after the last note fades.

Lee Dorrian’s role here can’t be overstated. Without him, Asgard might have remained a whisper in the dark. So here’s to Asgard, to Lee, and to the countless unsung heroes who keep the underground flame burning bright. We don’t know what else lurks in dusty attics and forgotten garages, but with releases like this, the magic of discovery feels as alive as ever.

“We really had moved away from the pop stuff.”

For the past 15 years, I’ve been neck-deep in the underground swamps of the late ’60s and early ’70s, obsessively digging through the dustiest crates and murkiest bootlegs. And then, boom, something new surfaces, just when you think you’ve heard it all. Does it blow your mind that after all these years, your music is not only seeing daylight but spinning on vinyl worldwide?

Richard Kilbride: I’m a retired elderly gent now, just me and the dog, with all the time in the world to walk the trails and travel off in our campervan. It truly is amazing that this dusty, mouldy old relic… not me… the recording, has finally made it onto the market. That 19-year-old, full of hope and dreams of fame and fortune, sitting in the studio adding the bass lines, would never have dreamt that it would take 55 years for our music—what little there is—to make it to marketable vinyl.

Alright, let’s drop the needle on Side A, where did you grow up, and what was life like back in the primordial ooze of your early days? Do you remember that first jolt of electricity from the radio, the songs that hooked you? And what were some of the first singles you shelled out your hard-earned cash for?

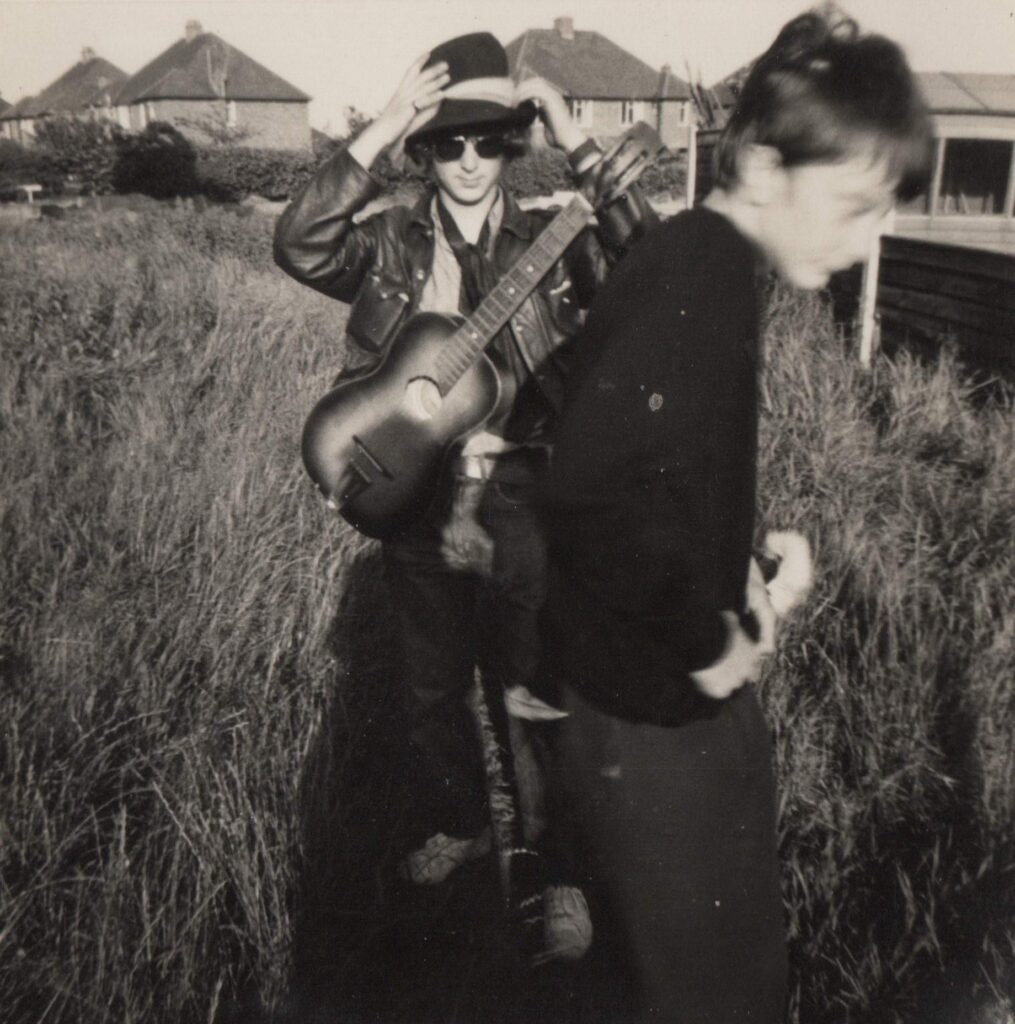

Born in Coventry, but a fair bit of my early years was spent in West Africa—Ghana first, then Nigeria. My dad was a construction engineer, and the family would accompany him on many of the contracts he worked on. I was 14 and in Nigeria when I bought my first record—an EP by the Rolling Stones, ‘Five by Five.’ I still have it. The first music to blow my mind, without a doubt, was at a friend’s house. His elder brother had bought the first Dylan album and was playing it. We were out in the garden, and I remember the absolute gobsmacking thrill of hearing something so different from the slick, Brylcreemed Elvis, Cliff, and Billy Fury. It made me want a guitar. I was 12, and my dad took me to the music shop in Coventry where I bought a Spanish acoustic. The first plucks on that certainly had me dreaming. However, I could not take it to Nigeria, so for a couple of years, all I had was the radio—until I got a battery-operated turntable with the speaker in the lid. I only had that Stones record, so it got played to death.

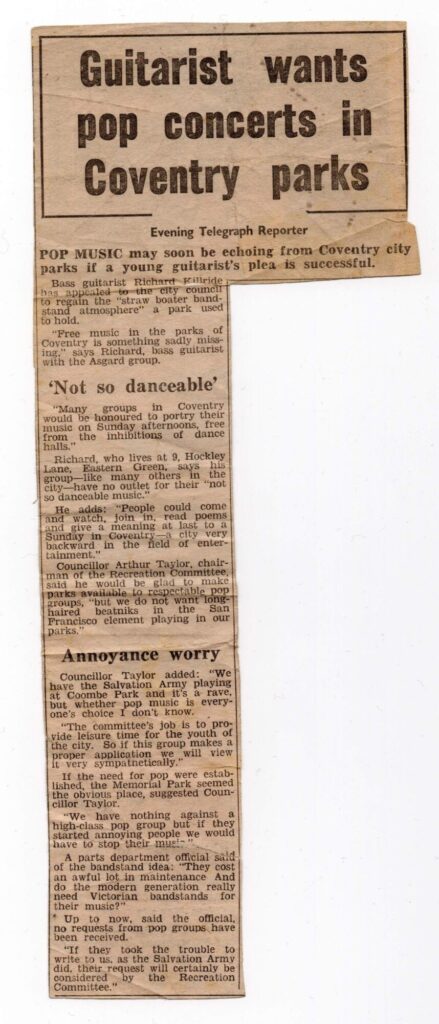

What was Coventry like back then? The scene, the people… or was it all just grey factories and bus stops with a secret underbelly of freaks waiting to explode?

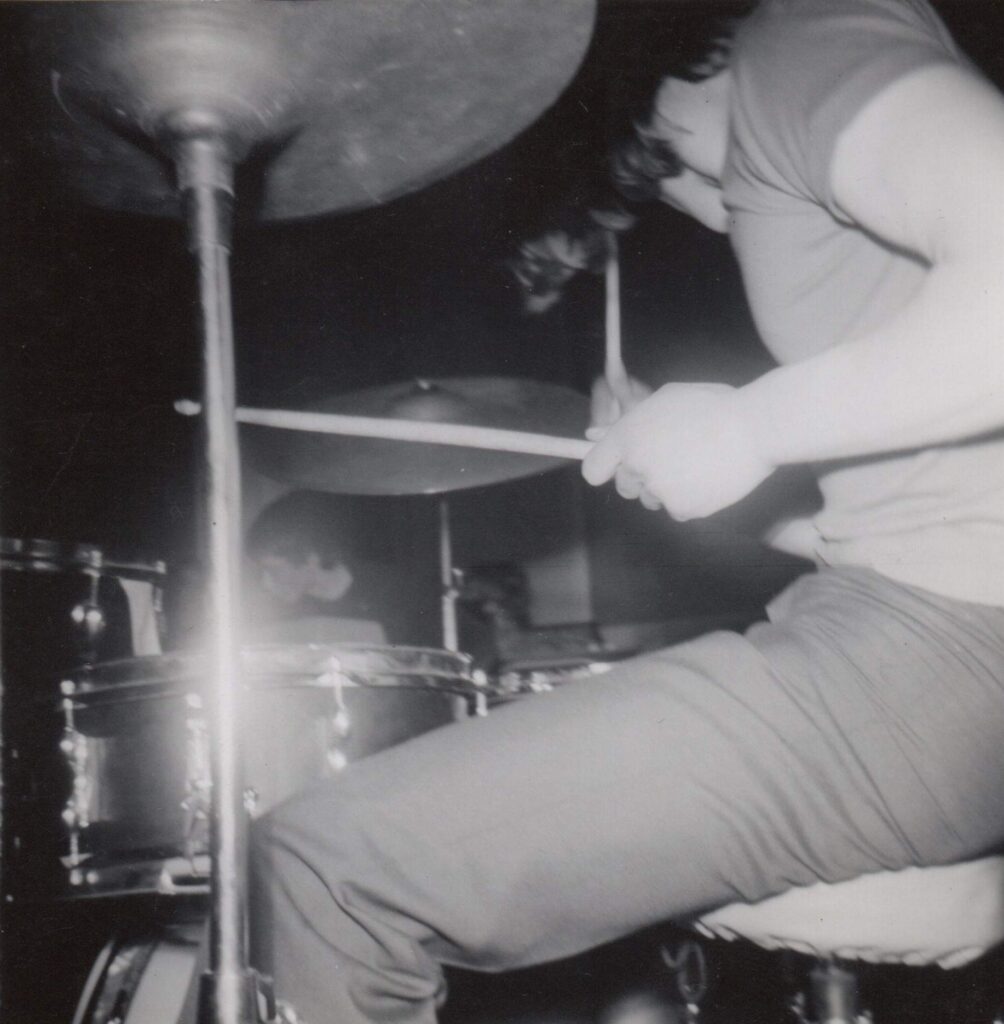

My earliest memories of Coventry were of a city recovering from the war, a new modern city centre being its pride and joy. The hundreds of maroon buses circling Broadgate around the statue of Lady Godiva. Coventry was the car-building capital of Britain, with factories churning them out and the ancillary suppliers. It did seem a grey place, and I was determined not to work in a factory, and fortunately never did. The mods and rockers, the scooters and motorbikes were the symbols of youth. Me and Terry, Asgard’s drummer, both had scooters. Bill had a Honda motorbike.

Before Asgard, what concerts left a mark on you? Who did you see that made you think, “Yeah, that’s it—I need to be up there melting faces”?

Coventry was lucky to have the Coventry Theatre, a place where the major bands of the day used to come, in showplace tours, with multiple bands playing for around 20 minutes each. The first one I had the greatest pleasure to see included the Stones and Freddie and the Dreamers, but the one that truly blew my mind included Pink Floyd and The Nice. My school also held a concert and we were lucky to get a band called The Idle Race. They had a record in the charts, Skeleton on a Roundabout, the forerunner of The Move with Jeff Lynne. By this time, we had started the first band ourselves.

What flipped the switch in your brain that said, “Screw it, I’m gonna be a musician”?

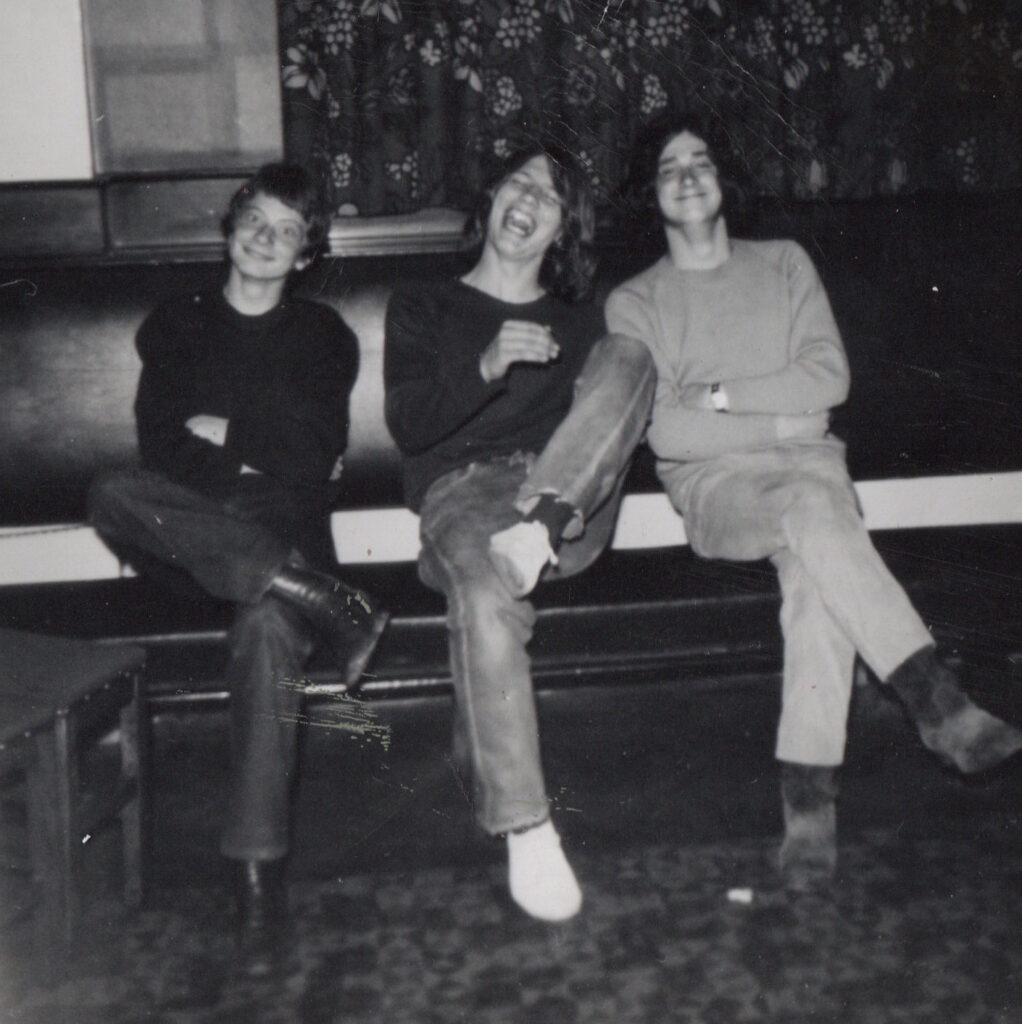

It was those shows that set my brain on becoming a member of a band. Bill and Terry were pals. Terry was in my class at school and we were inseparable. He too had the fever of wanting to play music. Bill was at a different school but lived two minutes up the road from where I lived. We were good friends and enjoyed our music. It just happened, as Bill had a musical genius and he infected me and Terry.

Any pre-Asgard bands you dabbled in? Proto-Asgard, if you will.

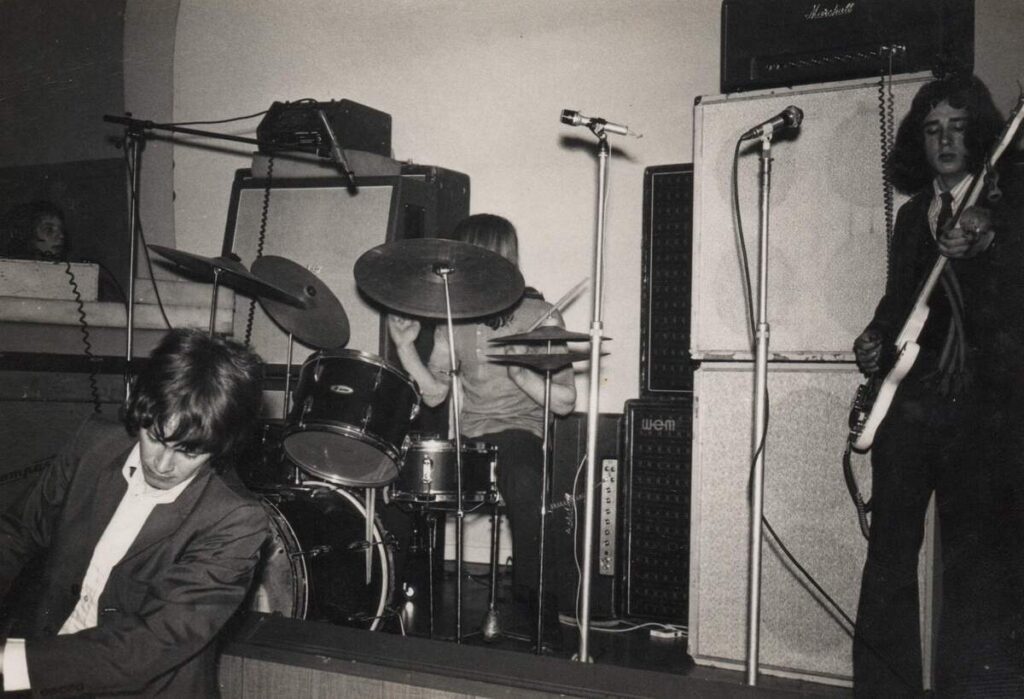

The garage at Bill’s house had a big room built on it. We called it the shed, and Bill had an accordion. Terry decided he wanted to be a drummer, and I bought an electric 6-string, took the top two strings off, and played it as a bass. We had another lad playing with us, Dave Cramer, a school pal of Bill’s, playing lead and vocals. Bill then got his mum to buy him a Farfisa keyboard, and the first band, Unions Jack, was born—a mod, Who, Small Faces-type pop group.

The name Asgard—straight out of Norse mythology, dripping in mystery and power. How did that come about?

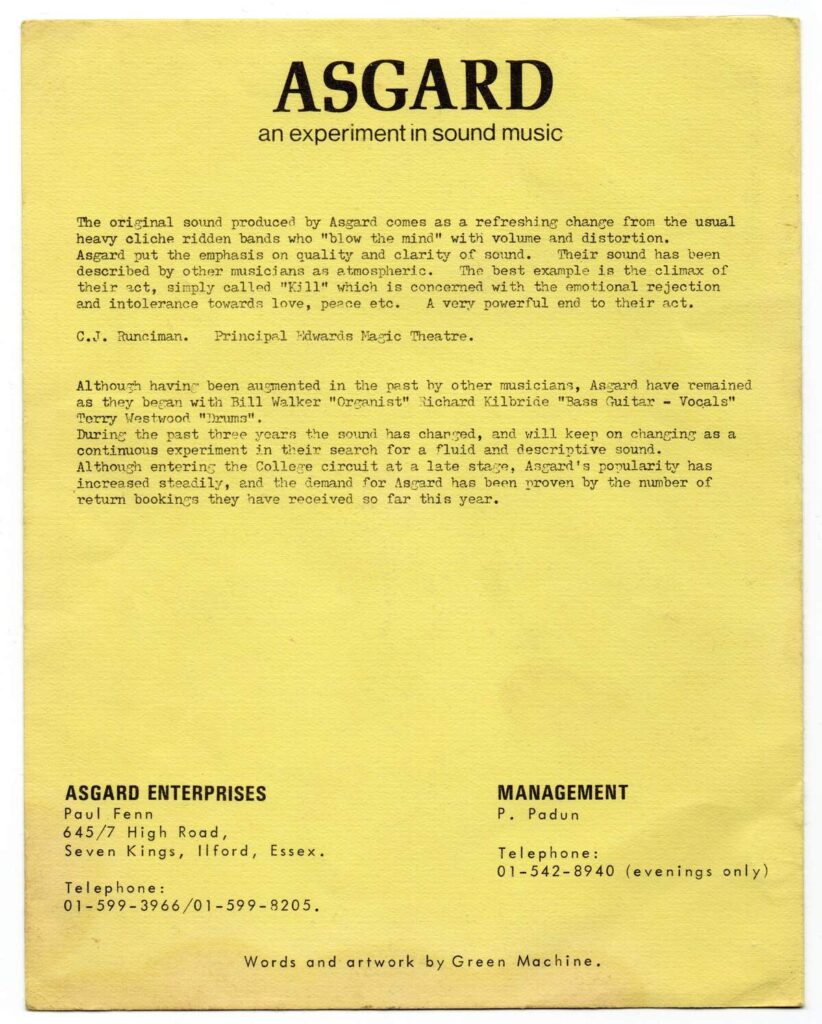

After about 6 months or so, Bill, myself, and Terry were listening to the Floyd, The Nice, Mothers of Invention, Velvet Underground, Spirit, Dr. John, etc. We really had moved away from the pop stuff. Dave didn’t like how we were improvising, playing in Bill’s shed every night. He didn’t want to move on to more experimental stuff, so Unions Jack ended and Asgard was born. I was into reading sci-fi and mythologies and suggested Asgard as a name for our new band.

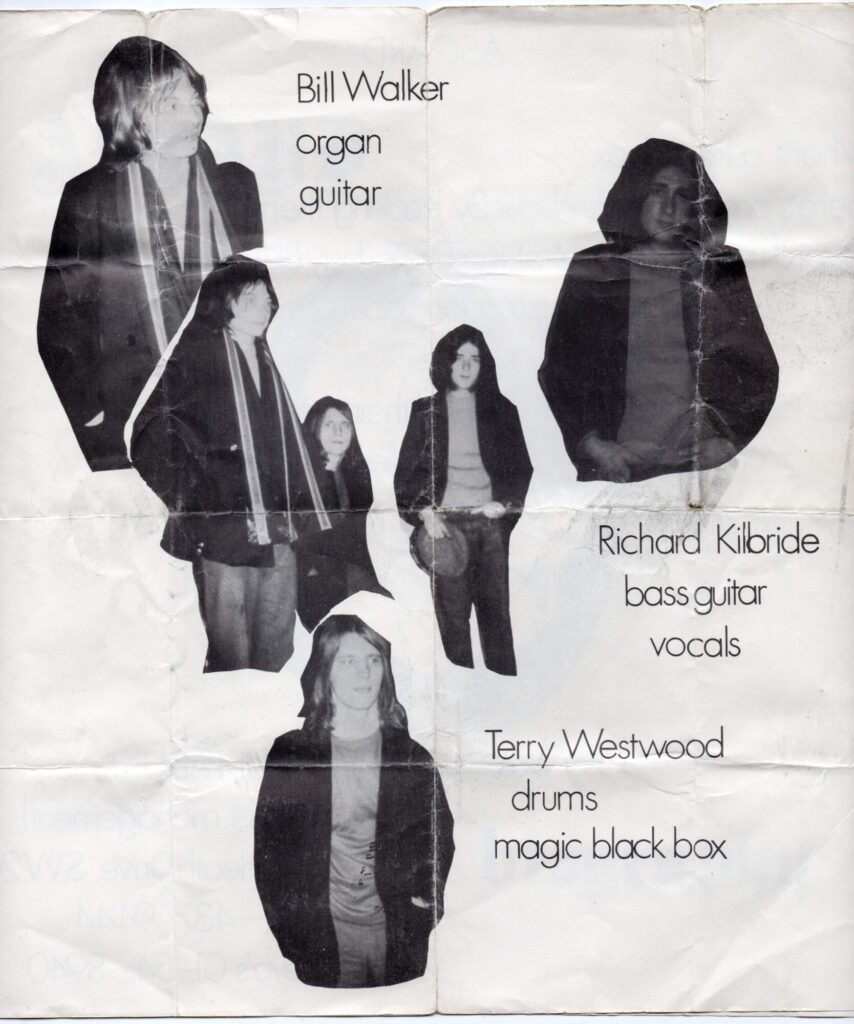

When did this beast officially come to life, and who were the conspirators who helped shape it?

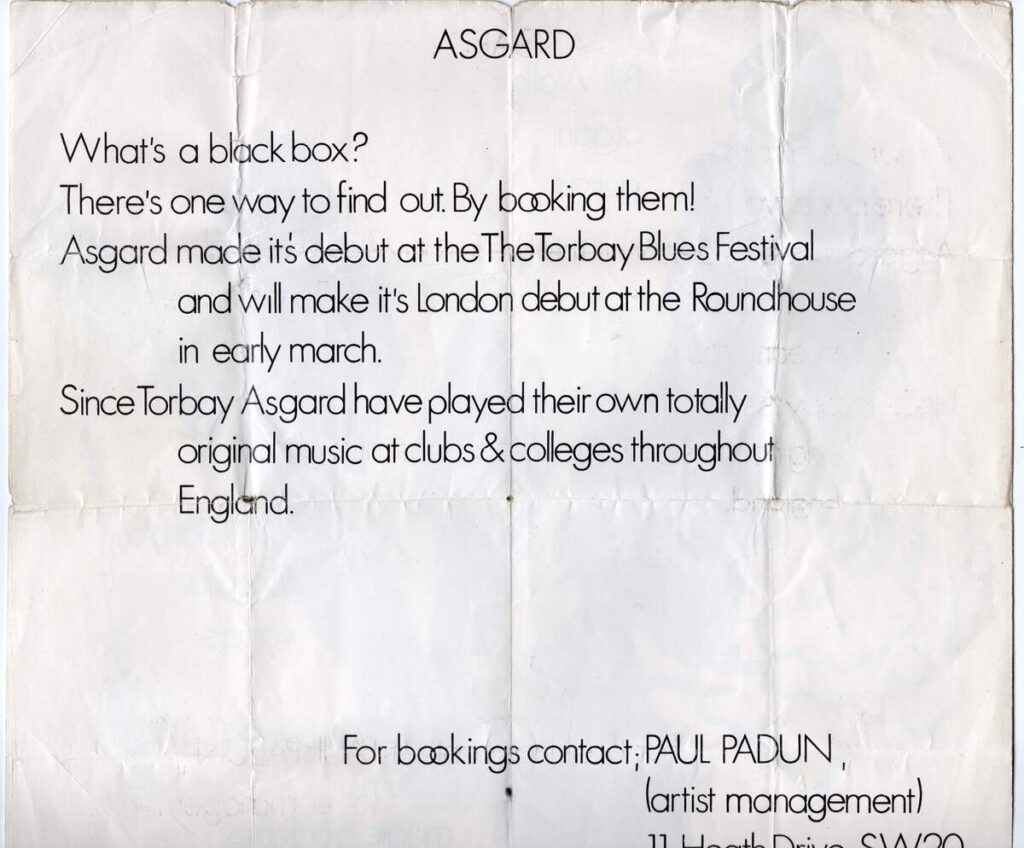

It came out of the sheer joy of playing together in that shed every available minute and going to gigs together. The first gigs as Asgard were very local to us—youth clubs, a few pubs too. By then, Paul Padun came into our circle. He drove the desires further.

Where did you rehearse—some dingy backroom, someone’s garage, a forgotten bunker? How did you buy your first gear?

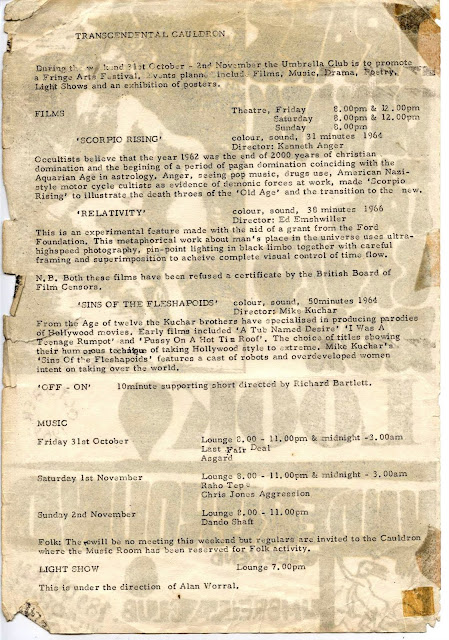

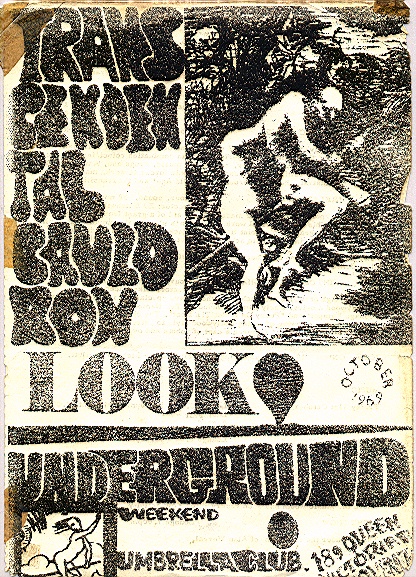

As previously mentioned, we rehearsed and swapped ideas, jammed and experimented in Bill’s shed. Sometimes we would attend an art club, The Umbrella in Coventry, that had a little theatre in its garden that held about 40 people. We would refine our sets there, open for people to come and listen. The shed became a hub for a bunch of friends who would sit in and listen to us play. Terry was doing an apprenticeship as a gas fitter and had palled up with Bob, who sometimes came to the shed. He knew a chap called Paul Padun, who was quite a suave bloke, and he suggested he manage us. Adrian Watton was also a good pal, and his musical tastes were very similar to ours. Along the way, he developed a light show and became a member of the band, and Bob, his wife Gill, were our roadies. Bill’s mum bought him his Farfisa. I bought a bass and amplifier on finance—nearly half my wages in those days. The same with Terry and his kit. I always look upon those days as being very broke.

“We loved experimenting with different concepts”

Was there, I don’t know, a concept or main idea of how you wanted to sound?

That grew out of our influences. We loved the Floyd and the Nice, and we loved experimenting with different concepts. Our sets came out of those dabbles. I would pen the lyrics, and the sound developed itself, really.

Lee mentioned Pink Floyd was an early influence—did you ever witness their UFO Club-era with Syd Barrett? Or maybe even Soft Machine’s freakouts?

Yes, but only once. At Mothers, he played with them. By then, Dave Gilmour had joined and Syd was on his way out.

And The Velvet Underground—how did you first stumble upon that banana cover?

I think it was Adrian. He would buy albums and bring them to the shed. I was in love with Nico in my fantasies at the time. That album was a standout moment.

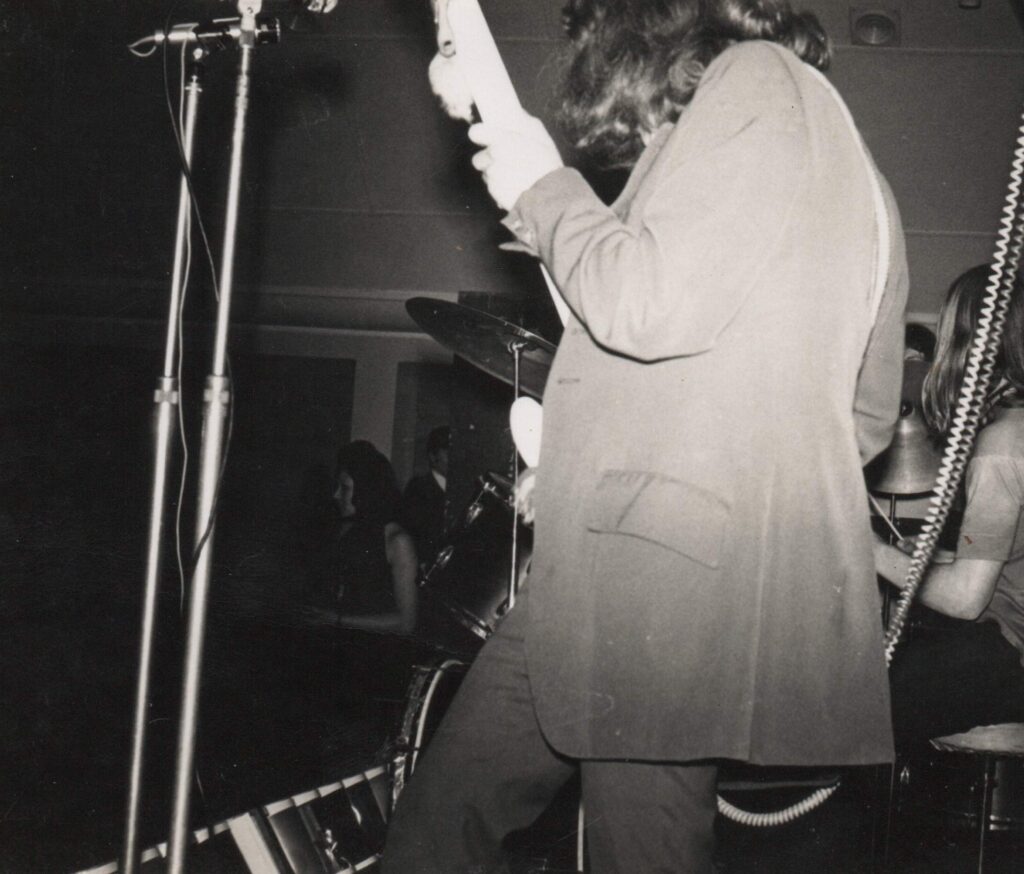

Any gigs that still burn bright in your memory?

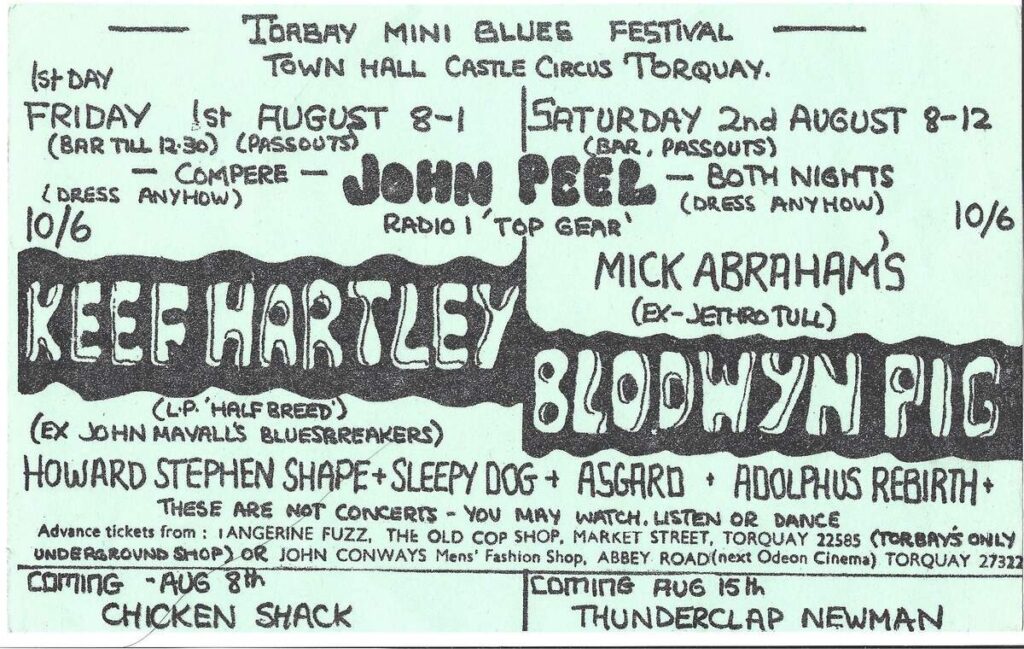

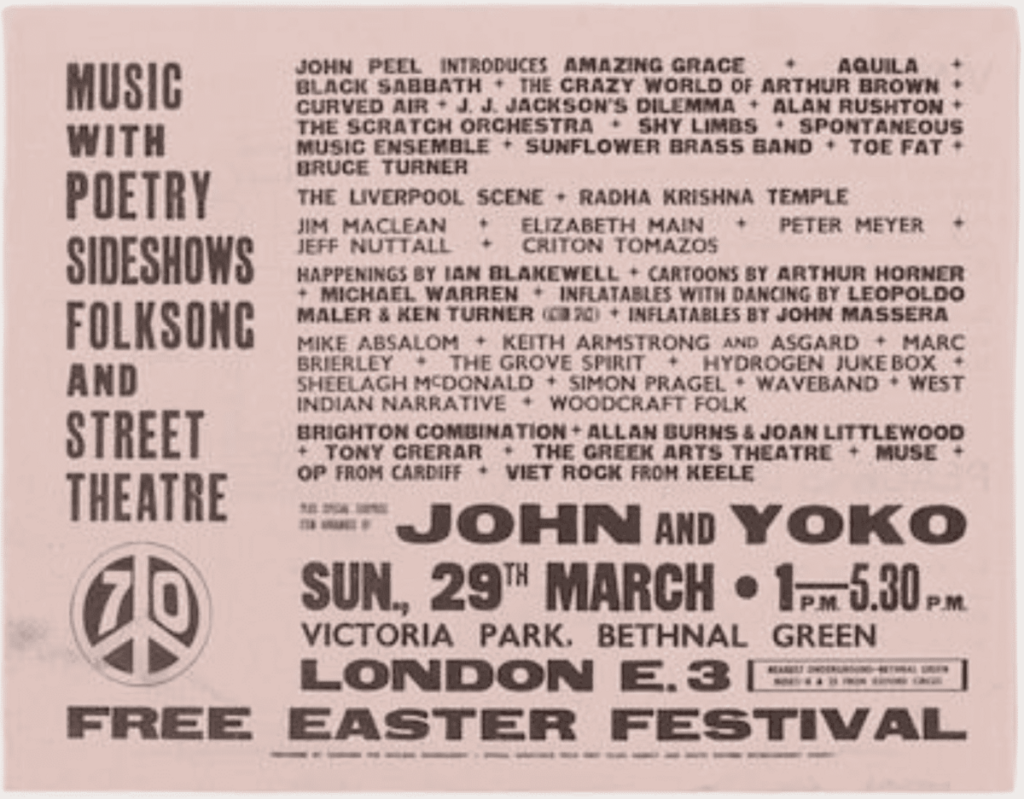

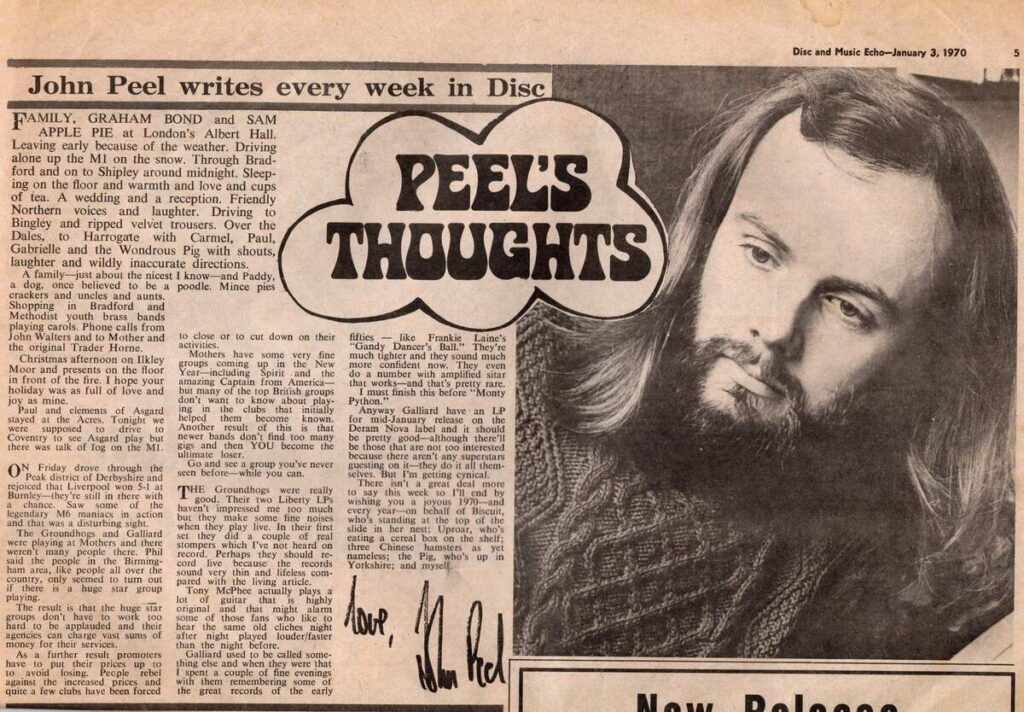

Many gigs hit the spot. The CND gig in Victoria Park, London, where we took Black Sabbath’s spot—for some reason they couldn’t make it. The Crazy World of Arthur Brown headlined, and Peel was MC. He also put us on at a small blues festival in Torquay, Devon, where we were supporting Blodwyn Pig.

They had transport issues, so didn’t make it. Peel asked if we would do their spot. We had already done our set, so we said we would improvise another. He introduced us as coming on again to save the night and pleaded for the audience to appreciate our desire to improvise a set. It was a total success, and Peel treated us to fish and chips after. We rinsed the back streets of Torquay looking for a chip shop. We entered one and got thrown out by the owner, who didn’t like long-haired hippies. Luckily, we found another.

What would be the craziest one?

Probably the one I’m most proud of was playing in the ruins of the old Coventry Cathedral at an arts weekend. We were told we had to finish at 11 p.m., as it was a Sunday. We were playing our finale, ‘Kill,’ and as we were finishing, the bells started to toll the hour. We joined in with the chimes. The audience went crazy thinking it was skill—it was purely a coincidence.

Did you ever get tangled up in management, or was it pure DIY? And what’s the story with Bob, your roadie—how did he wind up in Asgard?

Paul Padun was our manager, and he moved to London to try and get us gigs. He earned a crust by roadying a bit, got in with Alexis Korner and Pink Floyd. He introduced us to John Peel. We stayed at his house once—he wasn’t there though. In one room, he had built a Scalextric racetrack, co-owned by Marc Bolan. We were entranced by the amount of albums he had. What a night.

Bob Mansfield and his wife became our minders as well as roadies. We had bought a long wheelbase Transit—it had aircraft seats behind the front seats, and we felt like stars traveling in that throughout England. We couldn’t have done without him. We are still in touch today and attend a few festivals together.

John Peel—how did he first catch wind of you?

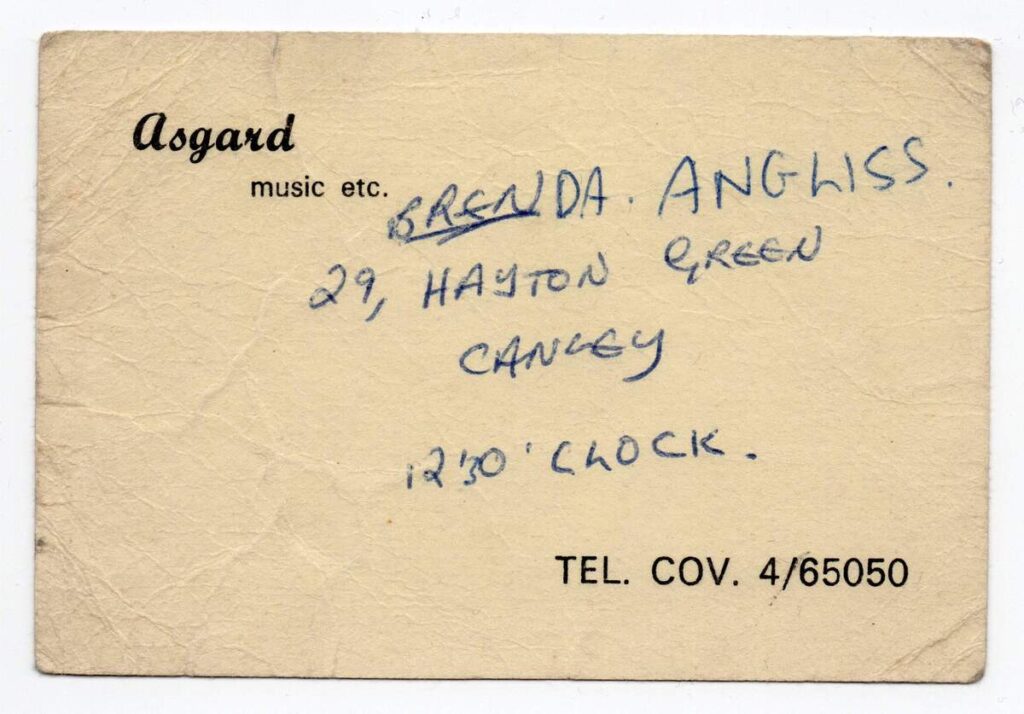

That was Paul. As I said, he had come into contact with him, and as we had made a few copies of the acetate, he gave Peel one to listen to—and he liked it. Paul became his pal. He even turned up in Coventry once in Peel’s campervan. Paul was very skilled in getting himself integrated into the music business.

“Peel offered us an album…”

He always had a radar for the odd, the raw, the ahead-of-its-time. Feels like Asgard would’ve fit his Dandelion Records roster perfectly. So, what the hell went wrong?

He offered us an album, but he had overstretched his finances with the other bands he had recorded. We would have had to pay for the studio time ourselves, and for an album to be recorded and produced was way beyond our means. We were holding jobs together and gigging all over. Our expenses with the van on finance—it was all way beyond us, unfortunately.

…But then you made it into the studio—three tracks on a one-sided 12” acetate. Spill everything. Was this before Peel got involved, or was this what got his ears twitching?

It was before Peel got involved, but only just. We financed that ourselves, but couldn’t afford a producer, so the engineer did his best—even let us use the Mellotron that features on ‘Sunrise.’

If we could have had it produced professionally… well, who knows. The idea was for Paul to take it around to A&R men, record companies, etc. I spent a day in London with him once doing just that. He had the cheek to knock on doors and try to get us a deal anywhere and everywhere. An exhausting day.

How much more material did you have? Was there ever a serious plan for a full album, or was it all lost to the shifting sands of time?

Oh, we had a good set list. All self-penned, but we would do a couple of covers. ‘Rondo’ by the Nice was an easy fit. We certainly had enough for an album or two.

When exactly did these recordings happen? What year are we talking?

The recordings have Bill playing the Farfisa Compact Duo, so it would be 1969. He later purchased a Lowry, similar to a Hammond, using that at gigs.

How long did Asgard last, and what led to the end? Was it a crash-and-burn scenario, or did you just quietly fade into the ether?

Asgard only lasted a little over 2 1/2 years. It was 1971 that we moved to North Devon to try and remodel our music. We had tried to recruit a guitar player in Coventry but we couldn’t find one that would gel into our sound. We also tried a few female vocalists, that Nico thing again, but no luck there either. So we decided to lock ourselves away in a cottage in North Devon that had a caravan in the garden. We planned to get part-time jobs and devote our evenings and spare time to evolving our sound, reinventing and experimenting. Unfortunately, the promised connection to the electricity main never materialised, and so we couldn’t rehearse at the cottage. We tried a few places to rehearse in, but lugging the Lowry—huge, heavy beast—was what we wanted to avoid, hence the cottage. The jobs we all had weren’t very secure, and Bill rethought his future, wanting to go to university. Bob and Terry wanted to reignite their careers in gas fitting. Myself, my then-girlfriend, and Adrian and his, decided to stay in North Devon. So Asgard unfortunately died. We got back together for one last gig in Bideford on the occasion of my girlfriend’s 21st, in 1972. That was our swansong.

And then, decades later, Lee unearths the lacquers. How the hell did that happen? And what’s it like knowing people are finally going to hear this after all these years?

Yes, it’s pretty mind-blowing. Fortunately, the acetate was salvageable and Lee came up from London over Christmas 2023. I handed over the acetate and some memorabilia that I had kept, and Lee performed a miracle in getting the acetate restored well enough to use to make the record. I’m extremely grateful. It’s just so sad that I’m the only surviving member of the band. Bob and Gill are still with us, living in Coventry, and Adrian is still in North Devon. I have kept in touch and they share the joy that, after such an age, Asgard are finally released in record form.

After the dust settled, what did you and the other band members do? Did anyone stay in music, record anything else, or did real life swallow it all up?

After uni in Bristol, Bill moved to London and played in a few pub bands. Terry often played with, and I joined with some musicians in North Devon in the early ’80s, in an excellent 6-piece band called Bo-Speak. A much different beast to Asgard. We wrote our own stuff and gigged furiously in Devon, having a good reputation. I thought Bo-Speak were good enough to make it. Our influences ranged from Talking Heads, Iggy Pop, Brian Eno, still Velvet Underground. We made a 3-track tape to sell at gigs. That was hiked around London to record companies and some interest was shown, but when we were offered a chance to tour full time, the drummer got cold feet. He was only young and was irreplaceable. We were a great rhythm section, along with a percussionist. That was my last foray into music.

What’s life like for you now? Any lingering connection to music, or did you move on completely?

Moved very much on. After Bo-Speak and losing the farmhouse we rented in North Devon, we decided, having now 2 children—one, a little girl Alice who was born severely disabled with spina bifida and hydrocephalus—to move onto a narrowboat, which we had built for us in Yorkshire. Unfortunately, Alice died a month before her second birthday, but we decided to move onto the boat anyway. I fitted it out myself. We called it Little Alice. That led to me spending several years fitting out narrowboats as a career.

And finally—cheers to this thing finally seeing the light of day. A true holy grail of underground sound. Last words are yours, say whatever you want.

Thanks for getting in touch with me. It’s been a bit of a rollercoaster the last few months. I’m thrilled that a bit of prog rock and Coventry music history has achieved being made available to a new and different world. Asgard gave me treasured memories and was a journey I hold most dear in my heart.

Klemen Breznikar

Rise Above Records Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / YouTube

great story guys………..I’ve had similar experiences…. 😉

Credit to Lee Dorrian for unearthing this fine collection and making it see the light of day and to Klemen for featuring the band here. One of the more listenable obscurities from that great era, Asgard was a pretty unique band with a unique sound and is worth the listen. Good interview too and the images that accompany it are a treat.