The Rediscovery of a Hidden Electroacoustic Pioneer: Romina Dezillio Brings Susana Baron Supervielle’s Archive to Light

Susana Baron Supervielle, born in Buenos Aires in 1910, lived much of her life in Brazil while maintaining close ties to Buenos Aires and Paris, where she became a pioneering figure in electroacoustic music.

Her work, deeply influenced by her experiences across these cities, represents a blend of modernist aesthetics and innovative sound techniques.

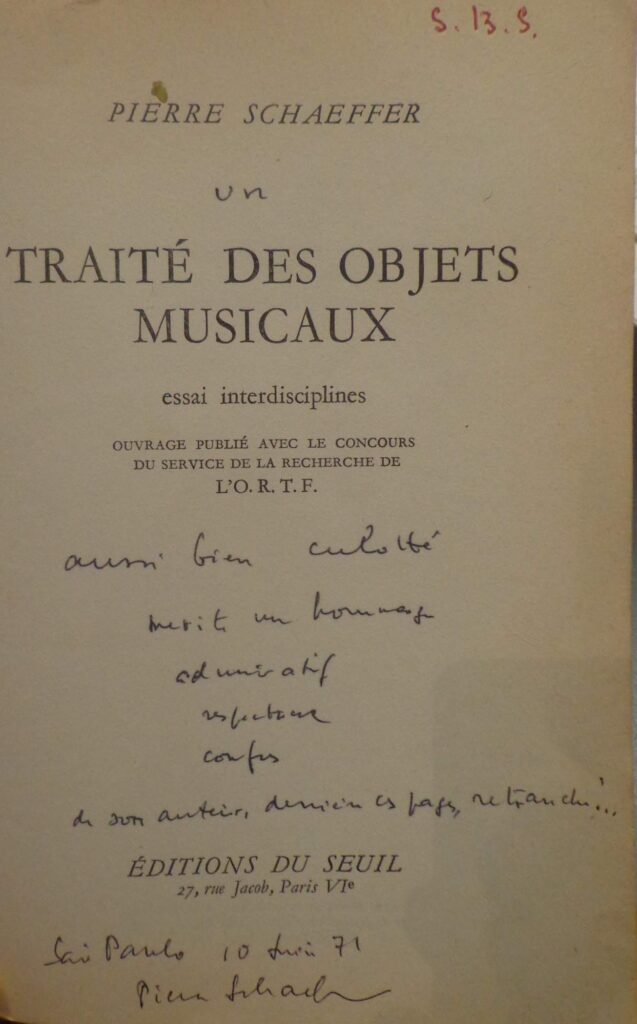

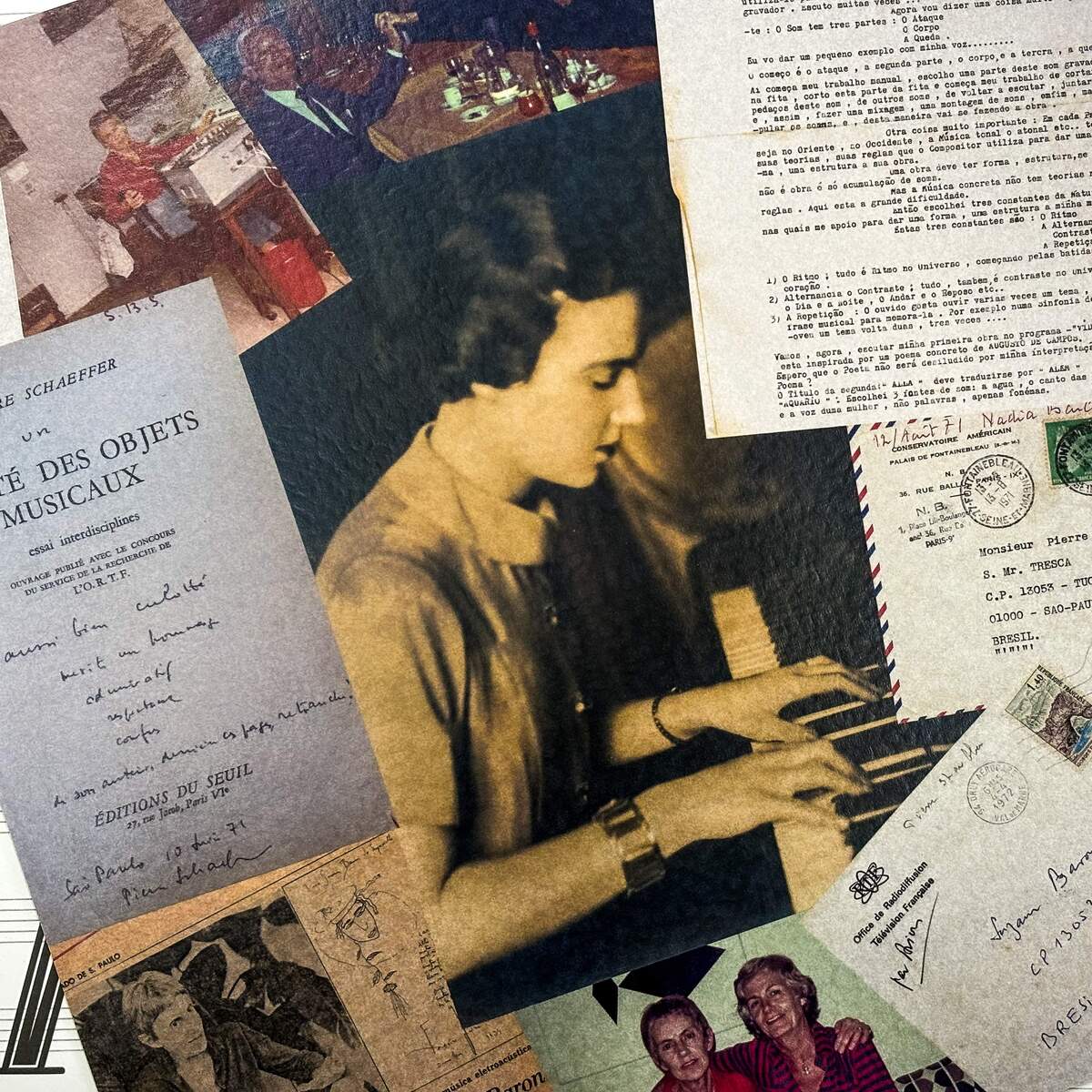

Inspired by Pierre Schaeffer and the Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète, she began experimenting with sound montage, using natural and urban sounds—as well as her own voice—to create music that transcended traditional composition.

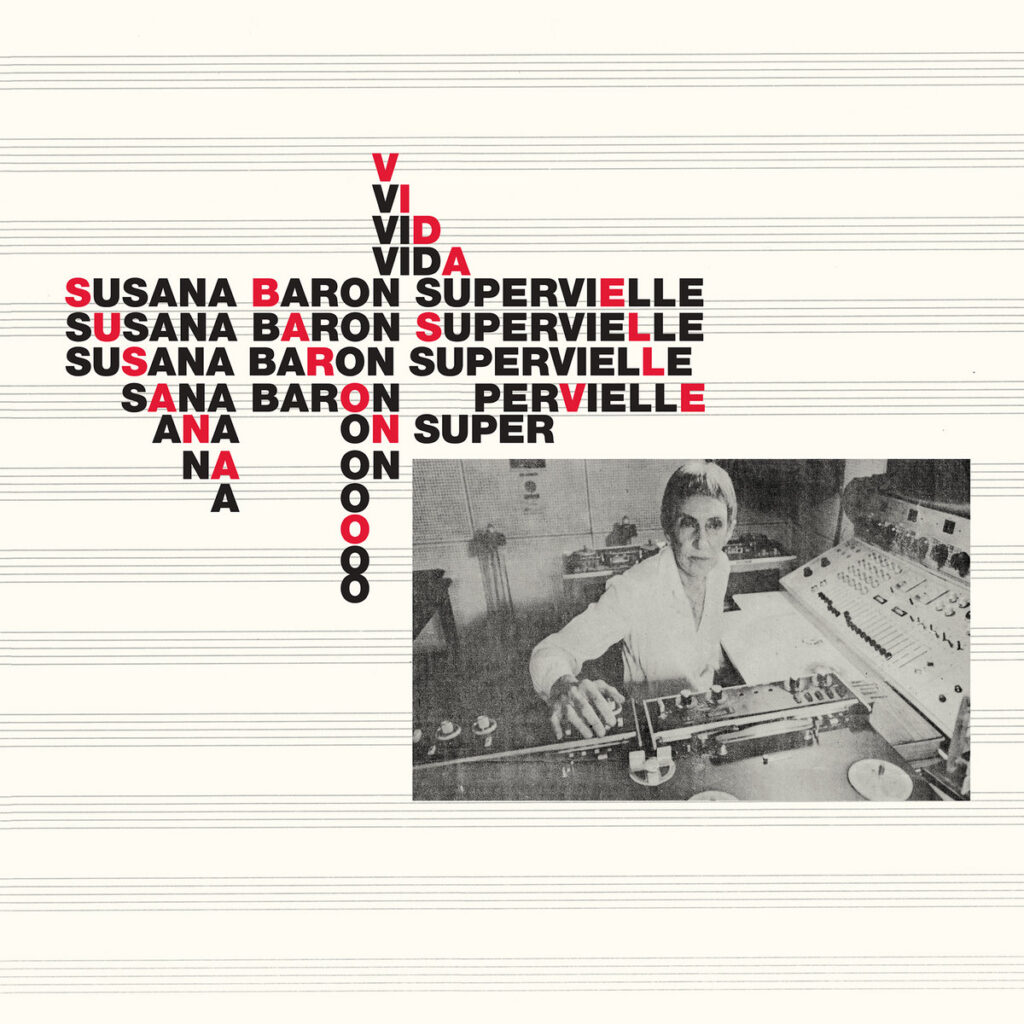

Baron Supervielle’s electroacoustic compositions, mostly created during the 1970s, remained largely unheard until recently. Musicologist Romina Dezillio has been instrumental in bringing these works to light, meticulously curating Baron Supervielle’s compositions and shedding new light on her artistic vision. The Wah Wah Records release of her electroacoustic works, along with the reissue of her album ‘Vida,’ showcases her innovative approach to sound and offers a rare opportunity to explore this underappreciated body of music.

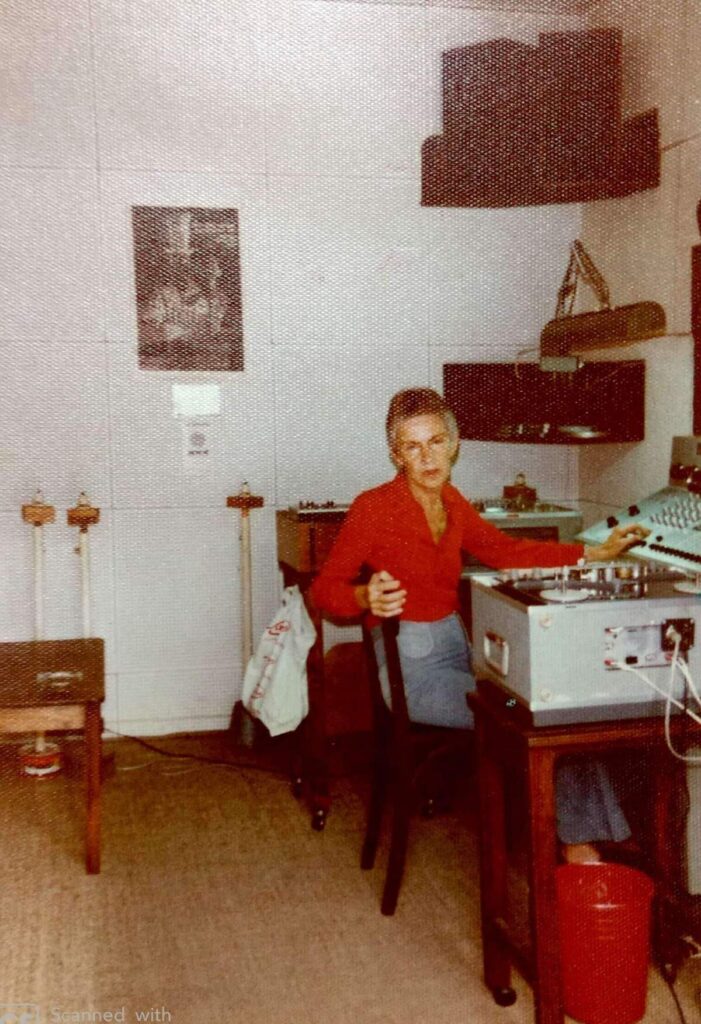

Dezillio’s research highlights Baron Supervielle’s use of sound materials to craft deeply poetic and existential narratives. Though electroacoustic tools were not widely available in Argentina at the time, Baron Supervielle’s privileged access to equipment enabled her to establish personal studios in both São Paulo and Buenos Aires. Her compositions are marked by simplicity, emotional depth, and a unique lyrical quality that continues to resonate. Once largely forgotten, her contributions to electroacoustic music are now being rediscovered—thanks to the efforts of scholars like Dezillio—ensuring that her legacy endures.

She was the first to introduce Schaeffer’s initial recordings (‘Étude aux chemins de fer,’ 1948) to Argentina as soon as it had been published in Paris.

How do you situate Susana Baron Supervielle within the broader historical context of electroacoustic music in Argentina and globally? What were her contributions that distinguish her from her contemporaries?

To situate SBS, we must keep in mind that she belonged to a wealthy and progressive-minded family of French immigrants settled between Buenos Aires and Montevideo during the 19th century, where they founded a bank that exists to this day. By the beginning of the 20th century, they had reached a solid economic position and engaged in patronage activities. They were all fond of contemporary arts and literature, so Susana received a privileged education and grew up in a very cultural environment, always up-to-date with European trends. Local and foreign artists, musicians, and intellectuals were frequent guests at her family’s home, and avant-garde manifestations were appreciated. Moreover, she was the niece of Jules Supervielle, a very well-known French-Uruguayan poet, close to the intellectual circles of literary modernity in Buenos Aires. In this context, Susana (born in 1910) was a pioneer in getting to know the experimental work of Pierre Schaeffer in the field of musique concrète at the RTF in Paris. She followed the development of the GRM from the very beginning and was the first to introduce Schaeffer’s initial recordings (‘Étude aux chemins de fer,’ 1948) to Argentina as soon as they were published in Paris.

However, as she had left Buenos Aires in the mid-1930s to settle in São Paulo, Brazil, with her husband, she did not participate in the sound studies and labs where electroacoustic music was first practiced in Argentina around 1960. Instead, she set up her own electroacoustic music studio at her house in São Paulo at the end of the decade, when she was almost 60 years old. Either way, her deep interest in electroacoustic composition and her active and up-to-date sociability enabled her to stay in touch with key Argentine figures in the field, such as Francisco Kröpfl, Fausto Maranca, Mario Davidovsky, Héctor Bozzarello, and Fernando von Reichenbach, from the first electroacoustic experimentations during the 1950s.

This ability to remain connected with other composers and musicians was the result of two main factors. On one hand, her membership in Agrupación Nueva Música—an association for contemporary music concerts in Buenos Aires led by Juan Carlos Paz, a pioneering promoter of dodecaphony—since 1950; and, on the other, the help of her sister, Odile Baron Supervielle, a prominent cultural journalist known for her work at the most important newspapers of the time. On top of everything was Susana’s widely known generosity and kindness towards composers and musicians from the various cities she used to stay in: Buenos Aires, São Paulo, and Paris. She knew how to cultivate deep friendships with important representatives of musical modernity, many of whom had been her teachers—such as Nadia Boulanger and the French mezzo-soprano Jane Bathori; Schaeffer and Pierre Boulez; the dodecaphonists Hans-Joachim Koellreutter in São Paulo and Juan Carlos Paz in Buenos Aires.

But there is another major gesture that Susana made toward the field of electroacoustic music—one that promoted its continuity in Buenos Aires and encouraged new generations to develop the genre. At the beginning of the 1970s, due to sociopolitical turmoil, two of the main studios were shut down: the one founded by Kröpfl at the Universidad de Buenos Aires (state-run) and the one operated by the Centro Latinoamericano de Altos Estudios Musicales, CLAEM (privately managed). While Susana had her own studio in São Paulo, where she created all her electroacoustic works, she had also set up another studio in Buenos Aires. It was located on the 11th floor of the same building where she had her personal apartment, where she used to stay during her periodical visits to the country. In 1971, Susana offered the facilities to a group of young musicians who were beginning to venture into the electroacoustic genre. That was when they started ARTE 11, a private studio that later evolved into a profitable enterprise, where the musicians created their own electroacoustic and experimental works, as well as commercials, TV and radio productions, and other commissioned music.

In your research on women composers from the early 20th century, how does Baron Supervielle’s work reflect or challenge the prevailing narratives about female musicians in the electroacoustic genre? What specific barriers did she face, and how did she navigate them?

Susana was a particularly independent woman, especially because of the support she always received from her family and her husband. She didn’t suffer domestic oppression, and her exceptional autonomy allowed her to manage her musical career thanks to her sociable skills and her frequent travels since the 1930s. Composition was the least legitimized activity for women at that time (despite the fact that there were many women composers). Women were considered—if not explicitly, then as an open secret—to be unsuited to speculative musical thought.

During the 1960s, we can talk about three other Argentine women composers of electroacoustic music, among others, who were quite a bit younger than Susana: Hilda Dianda (1925), who studied with Schaeffer in Paris and with Maderna in Italy; Beatriz Ferreyra (1937), who became a member of the GRM and never returned to Argentina; and Nelly Moretto (1925–1978), who was part of the first Estudio de Fonología Musical founded by Kröpfl. According to Ferreyra, she and Susana were close friends.

In the late 1960s, electroacoustic composition faced three main challenges: the availability of equipment; the handling of technique and familiarity with the aesthetic trends of electroacoustic music; and the bewilderment of the audience toward the genre. Although these situations affected both women and men, women had to contend with their subordinated status and segregation from the coveted spaces of development.

Anyway, Susana’s half-French nationality made things easier for her in many ways. First, her early contact with Schaeffer in Paris not only allowed her to learn the basics but also gave her access to his first books on the subject (such as À la recherche d’une musique concrète, from 1952). Apart from that, it was at one of the concerts organized by the Domaine Musical, founded by Boulez in Paris, that she first heard the work of Stockhausen, among others.

Concerning the equipment, as I’ve mentioned, her privileged economic situation gave her the exceptional possibility of owning her own sound processors and generators to install her own studio. Finally, concerning the reception of her music, Susana’s work was generally very well received by both audiences and critics, repeatedly praised for its lyrical appeal. Though her electroacoustic music was not widely disseminated, many of the works were performed at least once at the concerts organized by Agrupación Nueva Música during the 1970s. As an example, we can consider one review after the premiere of ‘Acuario,’ which mentioned that:

‘Acuario’ is a work that largely approaches the content of beauty that should characterize the artistic product. The piece refers to a whole world of lively experiences closely associated with the aquatic image, which seduce the listener. ‘Acuario’ reveals that its author possesses creativity and inventiveness despite the leveling effect imposed by the medium provided by the most advanced technique.

Considering the significance of the materials you discovered, including the electroacoustic tapes, what challenges do you face in preserving and accessing the works of women composers like Baron Supervielle? How do you envision the role of institutions like the Instituto Nacional de Musicología in safeguarding these legacies?

The main—and first—challenge in all my research was to locate the personal archives, because they were all private, and the available documents were isolated, scarce, and not enough to develop an investigation capable of making an intervention into the traditional historiography, which had left women out of the national history of music. Once I was able to reach each personal archive, under family care, I made my biggest effort to put them under the custody of the Instituto Nacional de Musicología, where I work, in order to guarantee open access for everyone willing to investigate the past of our women composers.

So, I think the role of institutions is crucial in safeguarding the national historical heritage. This is important not only to enlarge our knowledge concerning women composers, but also to expand the variety of works in the concert repertoire. Therefore, documented historical study and reconstruction are essential in two ways: on one hand, they provide a past in which women composers can see themselves; and on the other hand, they allow us to turn the legacy of our early female composers into a heritage.

Could you elaborate on the methodology you employed in studying Baron Supervielle’s repertoire? How did your approach evolve once you gained access to her unpublished materials, and what new insights did this provide?

I was first introduced to the music of Baron Supervielle around 2010 by my mentor Silvina Luz Mansilla. She had been in charge of writing a dictionary entry about Susana and had been in touch with her by post fifteen years earlier. I was looking for women composers to design my PhD project, and Mansilla recommended I explore her varied work (for solo piano, chamber ensembles, voice and piano, and electroacoustic pieces). However, since Susana had died in 2004, most of her works were not available at that time—my mission was to locate them.

During the process, my first contact with her music was through her last songs from the ’90s, a quite singular corpus of almost thirty pieces for a cappella voice based on poems by Alejandra Pizarnik (1936–1972). From the very first moment, I knew Susana would become a very different representative in my chosen corpus of first professional women composers, for many reasons. First (and very personal), I knew many of Pizarnik’s poems by heart—she is definitively one of my favorite Argentine poets—and I had no idea her poems had ever been set to music. Her intense, profound, and often melancholic poetry explores themes such as existence, identity, death, and the complexities of language. Though she is considered one of the most important voices in Latin American literature, the musicalization of her poetry had no precedents.

Second, the a cappella writing was also singular and curious for the Argentine chamber song. Lastly, all these songs had been recorded by a well-known mezzo-soprano from the contemporary music scene in Buenos Aires. Despite managing this information, the musical material was still missing.

Gradually, I started organizing the information I was researching until I was able to reach a niece of Susana, who had, by chance and very recently, found her musical archive and was trying to resolve what to do with the material. So, it was a very happy coincidence. When she discovered how interested I was in the material and that it could be guarded in a national institution (she was actually trying to get rid of it), she immediately donated many documents—scores, letters, concert programs, and recordings of many of her songs. The electroacoustic material was not among the items donated, but fortunately, it was found a couple of months later by the same person, and she left the tapes under the custody of the Instituto Nacional de Musicología “Carlos Vega.”

Once I was able to get involved with the material—which includes not only the music sheets but the recordings of almost all her songs—I realized how influenced by poetry Susana’s music was. Together with the scores, there were numerous loose sheets with selected poems. Memorabilia was another key element in studying her career, as it includes letters from important personalities of the contemporary music scene, concert programs of her own work, newspaper clippings with interviews, among others.

Susana Baron Supervielle wrote more than a hundred songs with different accompaniments throughout the twentieth century (from the ’20s to the ’90s), based on her favorite poets: French symbolists such as Apollinaire, Verlaine, Valéry, and Renard; along with Pizarnik, one very important part of her songs are based on poems by her uncle Jules Supervielle, and others on the work of the Spanish poet Federico García Lorca. For this reason, all my first studies about her work focused on this bond between music and poetry until the ’50s, considering ideas about translation (since she spoke, read, and wrote in Spanish, French, and Portuguese), migrant identities, and musical representation, among others.

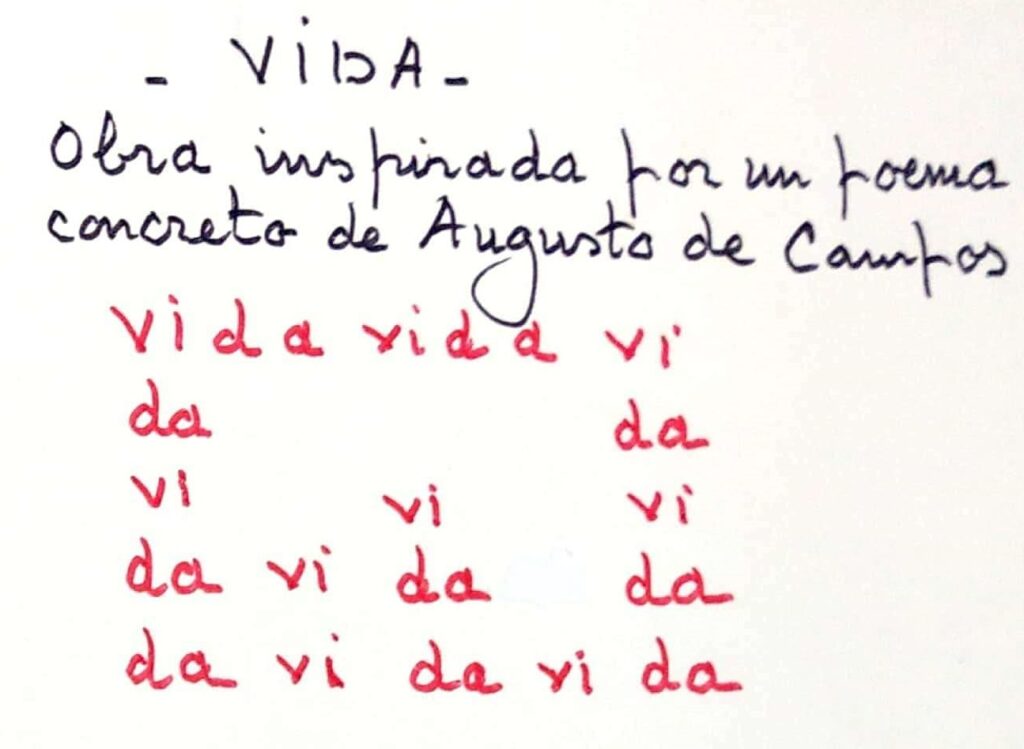

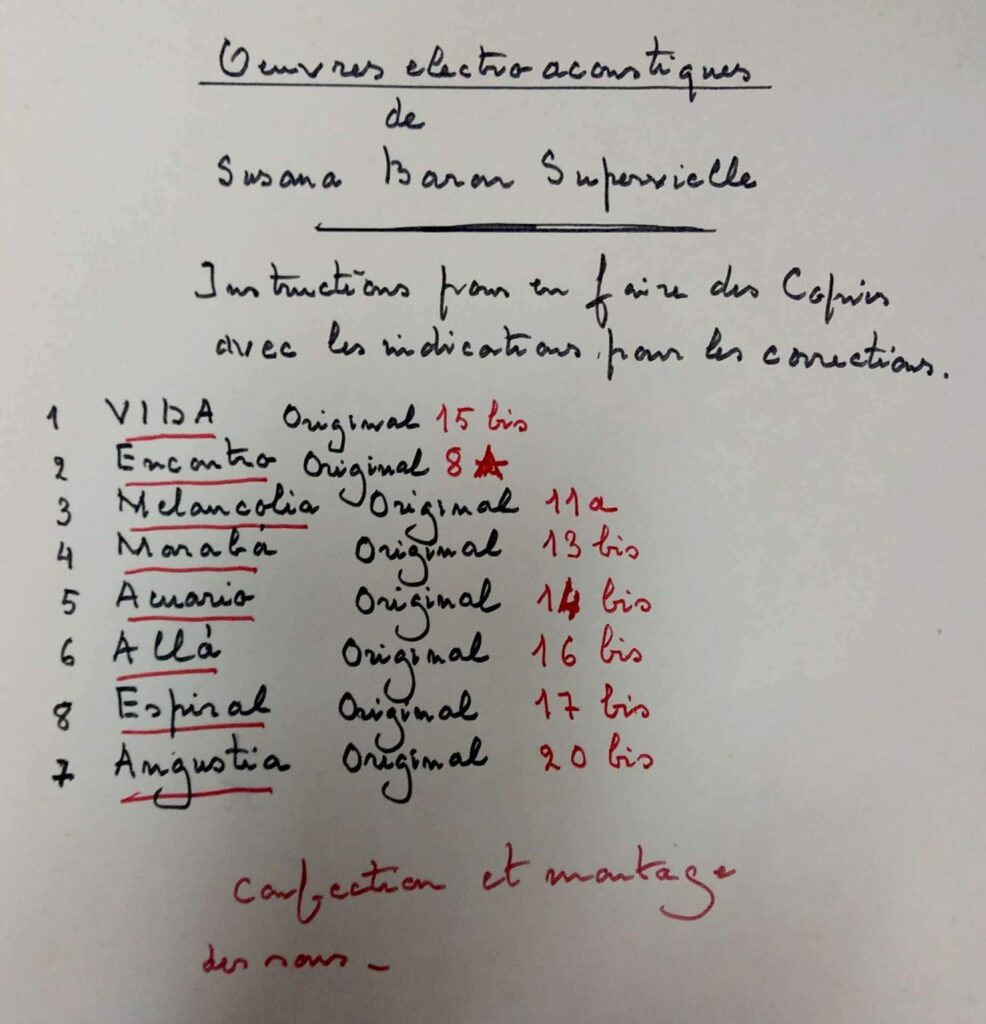

After this approach to her songs, I decided to study her electroacoustic music. We never found the original open reels, so I worked with the cassette transfers. However, the sound quality was acceptable, and the aesthetic proposal was very attractive and original. The link with literature persists in this corpus, with certain changes in the treatment of text that reflect the genre and the time period. Seldom is a complete poem included (the concrete poem in ‘Vida’ is the only exception); sometimes only hidden traces of them can be found (this is the case of ‘Poème’ by Pierre Lecuire, in ‘Melancolía’). Through electroacoustic music, Susana explores a different approach to literature, consisting of evoking the exuberance of the landscapes and the cultural melting pot in a way that recalls the descriptive resources of magical realism in Latin American literature (especially the boom of the ’70s), a reality in which the fantastic is frequently part of everyday life.

The electroacoustic corpus redefines the articulation between music and literature that runs throughout Susana’s work and allows us to consider this connection as the key element of her poetics.

“She set up her own electroacoustic music studio at her house in San Pablo at the end of the decade.”

In what ways did Baron Supervielle’s use of electroacoustic techniques advance the language of composition during her time? Are there specific pieces or techniques that exemplify her innovative approach?

Concerning technology, I took into account the precedent of her obsession with recording her own works, whatever the genre—something quite unusual for a woman composer from the academic tradition. Anyway, this trait distinguished her from most other composers (both women and men), who generally felt reticent to record their work, considering that sound recording involved a diminishment in sound quality and expression.

Concerning the use of electroacoustic techniques, what I can say is that Baron Supervielle was very honest and original, and also very well-informed. In this way, I would say her vast imagination compensates for the technical limitations. All her music is very personal and part of her own poetic-musical world, as I like to call it. As I mentioned before, she never gives up the search for beauty, the contemplation of nature, and the fascination with the new. I consider that the main significance of her music is aesthetic rather than technical.

To mention some examples: ‘Vida’ and ‘Acuario’ propose a kind of cosmogonic evocation; other pieces work with samples of electric soul music (‘Melancolía’) as part of the material; some include entire segments played on an electronic synthesizer (‘Angustia,’ ‘Allá,’ ‘Melancolía’) that recall the sound of radio and television productions by Delia Derbyshire. Also noteworthy is the presence of human female voices, which include actual singing (‘Vida’) and a variety of effects connoting grief and discomfort, in the manner of a sound language of sensations—moans, sighs, cries, gasps, disturbances (‘Angustia’). Finally, sounds of nature, African rhythms, and ethnographic recordings are also central sound materials in Susana’s works.

How has Susana Baron Supervielle’s legacy been recognized in contemporary musicology and performance practices? What steps do you believe are necessary to ensure her work receives the acknowledgment it deserves in the canon of electroacoustic music?

Her name is resonating a bit more nowadays, but mostly because of my own work. She had been completely forgotten until I started studying her and bringing her work to light. Of course, the release of the vinyl was a great thing. Otherwise, my research would have remained purely academic. Actually, Baron Supervielle’s electroacoustic works came as a total surprise to contemporary composers. Fortunately, other musicologists are studying the legacy of other women composers of electroacoustic music in Latin America. Thus, I think collaborative work is the most fruitful. In fact, I started studying the corpus with musicological purposes only, and it was my work colleague, Zelmar Garín, who is in charge of the sound restoration and digitization laboratory at the Instituto Nacional de Musicología, who proposed I send the material to Jordi Segura, the founder and owner of Wah Wah Records, a record store and label in Spain. Jordi got enthusiastic and became interested in including it in Wah Wah’s catalog.

Given the discoveries you’ve made regarding Baron Supervielle’s work, what future research directions do you see as crucial for furthering our understanding of her contributions? Are there specific areas or themes that warrant deeper exploration?

I think her songs deserve more attention; the bond between music and poetry is unique and wonderful in her work. But also, her instrumental music is beautiful, and studying it in the context of her influences would be great. At the moment, I’m planning to establish some kind of dialogue between her electroacoustic music and the work of her Argentine women contemporaries during the 70s, to further explore her personal style.

How did Susana Baron Supervielle’s early musical education in Buenos Aires shape her later explorations in electroacoustic music? Can you identify specific influences from her teachers, such as Gilardo Gilardi and Juan Carlos Paz?

I don’t think Gilardi had anything to do with her electroacoustic explorations. She attended orchestration lessons with him. Juan Carlos Paz could have been a reference, although she highlighted him for teaching her the dodecaphonic technique. In my opinion, apart from her lessons with Schaeffer, who guided her first steps in electroacoustic experimentation, she must have been largely self-taught.

What motivated her move to Paris in 1945, and how did her experiences with the Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète influence her compositional style and approach to sound?

At the time, traveling to Paris to learn about the latest musical tendencies and techniques was a common practice for her and for those with her social status and economic position. I suppose she thought it was the best option and went for it. Even though she mentions the year 1945, it must have been around the 1950s (considering contextual information, 1945 is too early even for Schaeffer). Schaeffer was the influential authority who made her inclined toward concrete music (if we consider electronic music as the other—the German—branch of electroacoustic experimentation). She was fascinated by the idea of including any kind of sound into her musical work, seeing it as an expansion of endless possibilities. But when it came to procedure, I would say she was quite iconoclastic, heterodox, and, if I may, disobedient (not in a conscious way, but as a result of her very personal style, which allowed a place for intuition within her expression).

Can you discuss the significance of her studies with Nadia Boulanger in the context of her development as a composer? How did Boulanger’s teachings impact her understanding of music theory and composition?

Susana’s studies with Boulanger were highly significant, as her lessons were the only formal education she received in traditional composition techniques. Moreover, Boulanger was considered a paradigmatic authority in modern music. Although Boulanger had many Argentine students over the years (including the famous Astor Piazzolla in the 1950s), Baron Supervielle was, if not the first, one of the first, in 1928. Since Susana had not attended classes at the National Conservatory (as most of her contemporary women composers did) because she found it too traditional and outdated, her studies with Boulanger served as her introduction and a factor of legitimacy for her work as a composer of modern music (which, at that time in Buenos Aires, essentially meant neoclassicism). They remained in touch until Boulanger’s death in 1979. Susana would visit her teacher during her periodic trips to Paris, and there are letters confirming that she would send her works for feedback. Boulanger’s responses were positive, and she encouraged Susana to preserve her personal freedom.

Susana Baron Supervielle had a unique cultural background, having lived in Buenos Aires, Paris, and São Paulo. How did this multicultural experience manifest in her compositions and artistic philosophy?

Susana was curious, enthusiastic, sociable, and generous, so she was able to take advantage of every place she stayed and connect with local artists in each city she lived. However, she was deeply committed to her Argentine identity and always presented herself as such, persistently doing her best to stay in touch with the local environment. Her artistic career was an undeniable result of this multicultural experience, not only in the formative process, as I’ve already mentioned, but also in the creative one—musicalizing poems in three languages (French, Spanish, and Portuguese). Her electroacoustic music is the most evident example, as listeners can easily recognize the multicultural origins of the sound materials. The migrant development of Susana’s career can also be seen in the way she promoted her own music: contacting musicians in each city to perform and record her work; personally managing the dissemination of her music through the media (such as RTF in Paris) and various cultural concert agendas; organizing festivals; participating in local associations; and creating connections between foreign and local artists.

What do you consider to be the most groundbreaking aspects of her electroacoustic works?

Her electroacoustic works are very original, especially in the selection of material and the pursuit of a story to tell. The formal aspects of her works can be compared to those found in instrumental music, and although the sound processing is quite simple (since her equipment was modest) and mostly intuitive, everything feels refined and tasteful. For example, I would point to the development of crescendos and decrescendos.

Considering the sound materials, she works with a wide library of sounds and music: natural sounds (water, wind, whales, storms) and urban sounds (jackhammers and other tools) that she recorded herself, as well as commercial recordings of classical and popular music, sometimes used in a very open and unmasking way. In addition, she included ethnographic recordings (probably borrowed) and recordings of her own voice or synthesizer performances.

The construction of meaning is the feature I find most original and interesting in her electroacoustic music. Her poetics are simple, sometimes concise (as in ‘Acuario’—female voice, whale singing, and water)—but the result is profound, overwhelming, and absolutely beautiful. I believe this is due to the creative connection her music has to poetry, a bond that brings an existential emotion and a unique depth to her work. This must be the reason why her electroacoustic music, largely unpublished and scarcely spread in her time, has been so well received today.

How did her marriage to Jorge Tresca and her subsequent move to Brazil affect her career and opportunities as a composer? Did her location impact her musical output or reception?

As I mentioned before, she was somehow able to take advantage of this situation. Everything resulted in a positive and expanding process, through which she benefited and always managed to contribute to her surroundings. She was, in fact, some kind of ‘citizen of the world,’ as people say, but her heart was in Buenos Aires.

In your view, how does Baron Supervielle’s work reflect the socio-political climate of Argentina and Brazil during her lifetime? Are there specific pieces that illustrate her response to these contexts?

This is something I can’t say for certain. She didn’t seem to have been dramatically affected by the socio-political climate, at least I haven’t found any evidence of it. If she was, she must have been able to manage it.

What challenges did she face in gaining recognition for her work, particularly as a female composer in a male-dominated field? How has her legacy evolved over time in contemporary music circles?

I believe the key features of her career as a composer throughout her life were professionalism and generosity, both fueled by an unbreakable passion. She didn’t seem to feel constrained by external factors. In fact, she embraced Boulanger’s call to live intensely through music as a life rule, continuing to compose until 1998, when she was 88. Her legacy was forgotten for many years and still awaits fairer recognition. However, the release of the vinyl has made an important contribution in that direction.

Thank you for your time. The last words are yours.

I appreciate this opportunity and your interest in Susana’s music and in my humble work about her. I hope this serves as a good incentive for listeners to experience her unique and meaningful music.”

Klemen Breznikar

Thank you so much for this brilliant piece! What a fascinating person, life and legacy.