Stud Uncovered: An Exclusive Interview with Houston’s Lost Hard-Rock Trio

In the dusty backstreets of Houston, 1974, three young musicians forged a sonic detonator called Stud.

With only a few copies pressed, it was a private hard-rock artifact, a gem that vanished into the ether, cloaked in pseudonyms and whispered myths. Tim Williams, seventeen and an already skilled guitarist, wore down his frets with solos that slashed through the mix. Paul Eakin’s Rickenbacker bass, a crazy engine propelling each riff. George Lasher’s drumming was rock incarnate. Barons Studios in Rosenberg became the crucible where intense teenage energy transmuted into twelve-minute psych excursions, boogie grooves, and hard-rock. ‘A Woman Like You’ hits like a glinting knife, ‘Captain Boogie’ grooves with a subtle edge, and the heavy intensity of ‘The War Song’… The centerpiece, ‘Stud,’ sprawls over twelve minutes of hypnotic jam. Lost for decades, rediscovered in 2015, the album now sits proudly alongside other heavy artifacts from the forgotten era, and especially in the archive of Texas rarities. Let’s unlock the unfinished story with this interview about Stud.

“We wanted our music to be powerful, beautiful, and sensual.”

Let’s rewind a bit. Where did you and the rest of Stud grow up, and what was life like back then? Any unforgettable moments from that time that shaped you?

George Lasher: I grew up primarily in Tulsa, Oklahoma (1955 to 1961), Houston (1961 to 1964), and Sugar Land, Texas (1964 to 1971). My world progressed from Howdy Doody, Roy Rogers, Sky King, playing Cowboys and Indians, Soupy Sales, Stan Musial, Ted Williams, Mickey Mantle, rotary dial telephones, the Kennedy assassination, Nolan Ryan, bowling, and Little League baseball. Those were America’s golden years, when you could leave your front door unlocked, and before Halloween candy became something that might kill you.

I bowled and played baseball; I was pretty good at both, up until 1965 at the age of 14, when my burgeoning love of music and rhythms led me to begin playing the drums (a birthday present from my dad). I had displayed an aptitude for percussion even as a toddler, driving my parents, and soon my teachers, nuts by habitually banging on any surface that produced sufficient noise. I cherished that initial set of drums: red sparkle Ludwigs, with wood shells, built-in dampeners, Ludwig hardware, Zildjian cymbals, and a Ludwig Speed King kick pedal (John Bonham’s favorite). I took lessons for three months, conquering the basic rudiments before deciding to go it on my own.

Tim Williams: I was born and shortly lived at a U.S. Air Force base in Wichita Falls, Texas. My dad moved us to Houston, Texas early in my childhood, and I lived there until I married, went on the road as a traveling and recording musician, and moved to Dallas, Texas.

Paul Eakin: I grew up in a suburb of Chicago, and I remember President Kennedy being shot, and Vietnam was something that hung over the heads of every young man, since you had to sign up for the draft when you turned eighteen. I remember the civil rights marches and Dr. King’s assassination. So, it was an intense time, but you tend to be insulated in your own world as a kid, which is why it seems even more intense to me now, looking back with the eyes of a parent and grandparent at that era.

When did you first fall in love with music? Can you remember those early hangouts, clubs, or dive bars where the rock crowd would gather, and the air was thick with possibility?

George: As an infant. My dad played trumpet during his high school years and during the years he spent in the Air Force. Subsequently, I grew up in a home filled with tunes from Louis Armstrong, Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman, and other big bands from the 40s.

I recall places like The Cellar, The Catacombs, and A Place Of Our Own, where you could occasionally catch excellent local bands like the 13th Floor Elevators, The Moving Sidewalks, Bubble Puppy, and Kenny Rogers & the First Edition.

Tim: It was at an early age. My sister, while she still lived in the household, had rock and roll records in her room, and she shared that music with me. The pinnacle of my desire to become a musician/guitarist came from watching The Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. I was six and a half years old. About a year later I received my first guitar and started lessons, learning and playing. I studied guitar basics, with notation, then studied Classical and Jazz. It drove my dad pretty crazy; I was supposed to be an athlete. I continued collecting albums and have kept some of them through the years. I got into playing for church in Houston, Texas, during the seventies. Not well regarded by parishioners or my parents (again), but you do what you are called to do. Paul was a big part of that at one church, and I connected with him. After a couple of years, I suppose, he introduced me to George Lasher and his drumming. We melded and began composing songs into what became the Stud album.

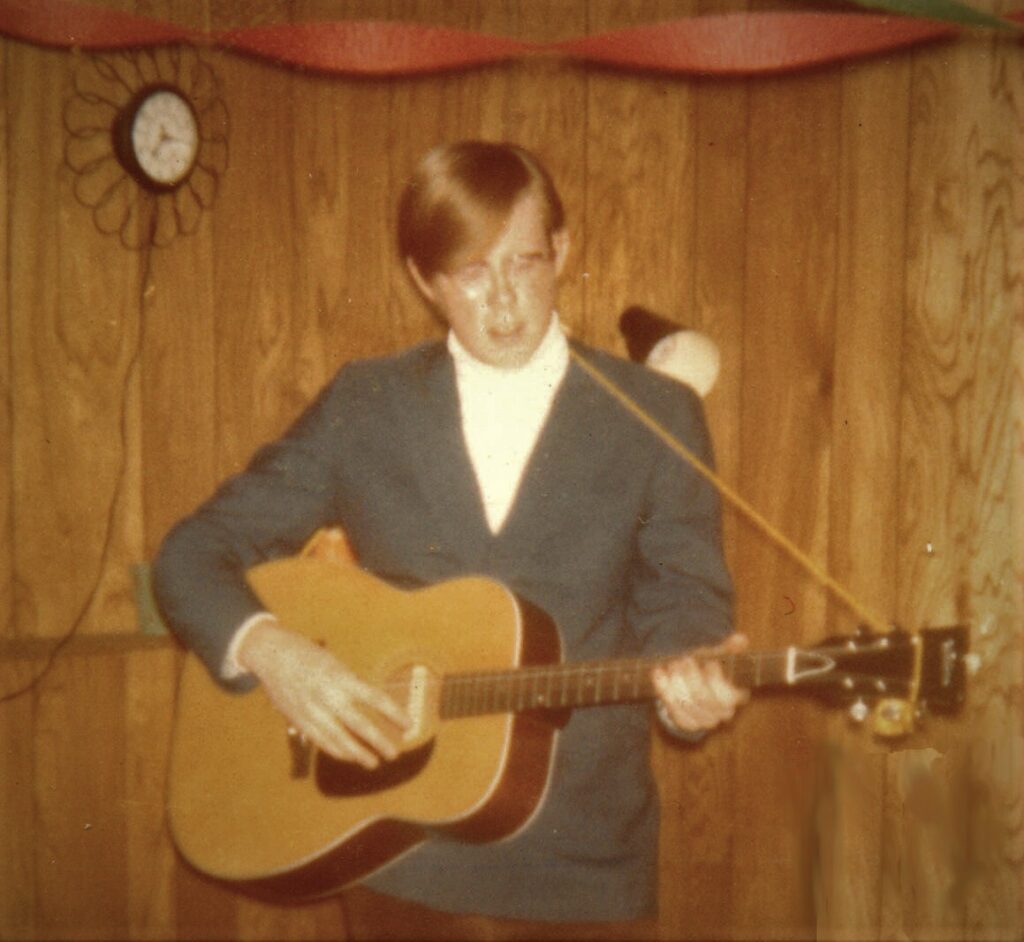

Paul: I learned to hate music first. My parents were both musically inclined, with mom playing piano and organ, and dad playing the violin. They thought it was important for me to learn how to play an instrument. I disagreed. I hated music lessons and refused to learn to read music, but I would play around on mom’s Hammond organ, and I could figure out songs by ear pretty quickly. One year, my grandparents gave me an acoustic guitar. It was nothing fancy, but it let me play along with my 45s.

That summer I worked at a camp for kids with muscular dystrophy. The camper I was paired with was two years older and ten times as cool as me. By the time I came home I had a list of bands I had to listen to, such as The Who, Cream, Led Zeppelin, Steppenwolf, Frank Zappa, Chicago Transit Authority, The Doors, on and on. I let my hair grow out. I bought a cheap copy of a Gibson SG, put together a Heathkit guitar amp with Radio Shack speakers in a homemade speaker box, and started to rock out with friends. Life was awesome and I was cool.

So, of course, right after Christmas that year we moved to Houston, Texas. It was the middle of my junior year in high school and I knew no one. I showed up at my new high school and was told I could not attend class until I got a haircut. It was January of 1971, but to me it felt like the dark ages.

That’s where my newfound love of music really helped me. I somehow found a bunch of other people that played guitar, drums, keyboards, bass, etc., and we’d get together and jam. It probably wasn’t good for the ears, but it was definitely good for the soul.

Did any of you have bands before Stud? What were they called, and do you have any forgotten recordings gathering dust in the back of a closet or some old cassette player?

George: In 1967 I formed a band (Dominion) with friends (Guy Gaughnard, Steve Long, Jim Wideman, and Gary Harper) from school. We played songs by The Beatles, Stones, Steppenwolf, Bee Gees, Cream, Spirit, The Yardbirds, and Kinks at church youth functions and at school dances. A year later we changed our band’s name to Quick Exit after being threatened with a shotgun by our bass player’s father, who became infuriated by the racket as we practiced in his garage while he attempted to take an afternoon nap. Our bass player swore to us that his pop’s shotgun wasn’t loaded, but we weren’t about to stick around to find out. By late 1968 we began playing gigs in nightclubs and bars until our lead singer’s ultra-religious parents found out. That occurred early in 1969 and spelled the end of Quick Exit, putting a temporary halt to my musical career.

Higher education came next, consisting primarily of chasing girls, listening to music, and reading The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy. I did, however, pay particular attention and excelled in one course: an introduction to radio broadcasting. My father had worked as a radio and television personality for as long as I could recall, and I soon realized that in my case, the apple had not fallen far from the tree.

In my music room closet, I have a test pressing of an LP by Quick Exit—at least I think it is still in that closet. That collection of tunes on vinyl was never released for public consumption. We also privately released a 45 RPM single from that album. On the flip side, the song was ‘All Shall Be New,’ written by bass player Jim Wideman and sung by yours truly. Damn, getting old is tough; I can’t even recall what was on the A side.

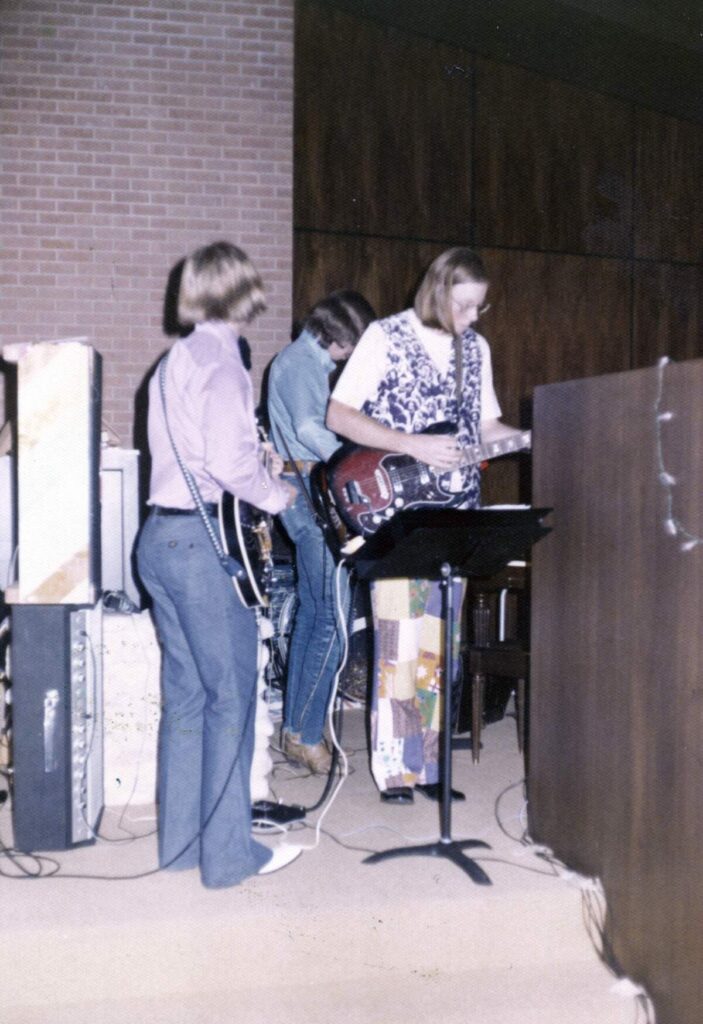

Tim: The Crystal Dove, a garage band that really went nowhere. However, over my high school days I would put bands together for dances at the school. Plus, there were church bands, several with Paul. Sorry to say, no music for historical (or humorous) pleasure.

Paul: I played with a lot of different versions of bands. I had a set of ten or twelve friends that played together in different combinations as different bands (whose names seemed to change every time they played), and I would practice or play with them when the opportunity arose. One time, a church was auditioning bands to play at a church party, and they had all four bands set up in their teen house so they could have them each play for fifteen to twenty minutes. I played in three of the four bands, and I think I played a different instrument in each, lol.

Whenever possible, I’d try to play with Tim. He knew more music theory at the age of twelve than I will ever know and is still one of the best guitarists I have ever known, and I’ve known some damn good ones.

Sorry, no forgotten recordings that I know of. However, Tim and I played together on an album before Stud, written and performed by the minister of music and choirs at Spring Branch Presbyterian Church in Houston. It was a rock musical based on the Book of Genesis. Somehow, you can find it on YouTube. Don’t judge. We recorded and mixed the entire thing in one day. We were very young.

So, what was the spark that lit the fire for Stud? What brought you guys together, and when did it happen?

George: I worked at KFRD AM and FM in Rosenberg, Texas, where I played country music as the early morning drive-time DJ, but on Saturday nights from 5:30 p.m. until 11 p.m. I had a wide-open, no-holds-barred rock and roll show called The Sounds of Today. I think it may have been in late 1973 or early 1974 that Paul heard the rock and roll show and called me. He said he played guitar and had a friend who played guitar. We decided to get together and jam to see if we enjoyed playing together. We did, and we began learning cover tunes as well as writing music of our own.

Tim: As I said above, Paul brought us together and introduced George into the fold. This happened, for real, in my junior year of high school. I was probably fifteen or sixteen years old at that time, a mere babe. All thanks to Paul. George was working as a DJ at a radio station in the southeast portion of the Houston area, where he was bringing rock and roll to that part of Texas.

Paul: I believe it was the autumn of 1973. Tim and I had been friends for a while and enjoyed playing together, and I think we were cruising in my car one Saturday evening, flipping through FM stations on the car radio looking for something good to listen to. We found a station playing some killer rock, and the more we listened, the more we enjoyed the songs and the DJ. We had never heard this station before, and for some reason we decided to go home and call them. I think we just wanted to thank them for playing such cool music. We probably expected to hear a pre-recorded message or a receptionist, but the DJ answered the phone. Turns out he was there alone, and he enjoyed talking to listeners. We talked for quite a while about music and rock and musicians.

That DJ was George Lasher, and we ended up going to the radio station to meet him. Everything just kind of clicked, and before long we were jamming together and starting to write and arrange some original songs. George had made some connections because of his job at a radio station, and it seemed like he had hundreds of friends in the music business. He already had an idea of what the band would sound like and had a vision of what an album would be like. Honestly, Tim and I somehow walked into this perfect scenario for a young musician: George had the drive, the contacts, even the name for the band. He just needed Guitar and Bass to go with his Drums. He was a good singer, and he was even a nice guy. I felt like I’d won a million dollars.

We worked our butts off, and by July 11, 1974, we had signed a booking contract with the Barons.

Let’s talk about the early days. How did you manage to scrape together your gear and set up? And where was the rehearsal space, the gritty hovel where you figured out your sound?

George: As previously mentioned, my father bought my drums for me. We didn’t practice in hovels — we practiced in my room at my folks’ house in Sugar Land, and upstairs in Paul’s room at his parents’ home in Spring Branch, as well as at the Rosenberg radio station.

Tim: Before I could legally drive, I’d hitch a ride with Paul in one of his parents’ cars, toting our equipment along. Our rehearsal spaces were usually in a garage — yeah, we were a garage band first — and hot as hell. We’re talking Houston, Texas summer heat and humidity. Fry-an-egg-on-the-sidewalk type of heat.

Paul: When we started playing together, we each had our own personal gear. I had a small Bogen P.A. amp and some cheap speakers and microphones we used as monitors for vocals (I think… it’s too long ago to remember all the details). We only used our amps for practice.

The Barons would put on “Super Sundays” at different dance halls in Southeast Texas. They would have several other bands play during the day for about an hour each, then do a quick switch, ten-second sound check, and the next band plays. There was always a great backline of guitar and bass amps, and they had a great drum setup. We only had to bring guitars and foot pedals, and I think George brought his snare and kick pedal.

We rehearsed anywhere we could — garages, living rooms. After I started working at a recording studio and we could practice and record there, it helped us tighten up our sound. We made some pretty good booking tapes.

What were your first gigs like? Was it a tough, chaotic mess, or was there some magic in the air that made it all worthwhile?

George: I remember some chaos, primarily in the form of a few mistakes (mostly on my part), but there definitely was magic in the air that motivated us to buckle down, intent on improving — especially when one of Rosenberg’s most popular bands (The Barons) offered us the opportunity to record an album at their studio, on their label. I imagine their motivation boiled down to the fact that I played their records on the radio. They did have professional equipment, including a very nice console and a 16-track Ampex recorder, as well as an isolation room for drums or other instruments.

Tim: Magic, tough, chaotic, messy — yes, and with higher expectations of myself than I care to admit. I could lay it in with the self-examination and criticism.

Paul: Most, if not all, of our gigs were the “Super Sunday” variety, where you had multiple bands. So you usually had at least three or four bands milling around backstage, either getting ready to go on or packing all your stuff up after your set to get it out of the way. That could turn into chaos pretty quickly because “backstage” was usually a tiny area.

Out front, the music was loud, there was plenty of beer, and the dance floor was always packed. Back in the 1970s in southeast Texas, around Houston, country music was big, obviously, but so were polka, western swing, rock and roll, and Tejano. It was not unusual to hear multiple genres from the same band — sometimes within the same song. I distinctly remember hearing a great version of All Along the Watchtower, but I had trouble understanding the words, and finally realized they were in Spanish.

Who are some of the bands you’ve shared a stage with over the years? Were there any bands that made you feel like you were part of something bigger, or that had that “hell yeah” vibe?

George: I hate to say I don’t remember any of the bands’ names, but Steve and Rusty Haygood were in one of them. Steve is a damn fine guitarist and Rusty is a keyboard wizard.

Tim: Well, we put together some shows and played some shows arranged by someone else (for instance, with our producers, The Barons). At first, we were the openers and eventually worked our way to headliners. I’ll share who we shared some “hell yeah” vibes with below. The biggest act that gave us existential hope was ZZ Top. Ever heard of them? Biggest little band from Texas!

Paul: There were a lot of good bands we played with, but nothing that sticks out.

Were there any local bands you clicked with? Who were the ones you’d run into backstage, share stories with, or just grab a drink after?

George: Was I in a band? Honestly, I simply don’t recall any bands that we clicked with or shared stories with.

Tim: We put on a show at a high school stadium on a Sunday, and the band I think that we clicked with was MudToad. What a name. They never really went anywhere, never went into the studio, but they had a great, raw, Texas boogie R&R groove.

Paul: For me, that kind of thing all happened after Stud. With Stud, we always seemed to be hyper-focused on ourselves and our writing. Plus, Tim was too young to drink at that time!

So, what was the vision behind Stud, if there ever was one? Was it to make some wild noise, change the world, or just make music that made sense to you guys?

George: Our name, STUD, wasn’t intended to be overtly sexual. A stud in a wall adds strength and provides support. A diamond stud in a gorgeous woman’s earlobe is a thing of tasteful beauty. A thoroughbred stallion exudes both power and sensuality. We wanted our music to be powerful, beautiful, and sensual. We wanted to make music that made sense to us.

Tim: The vision was to conquer the R&R world. Seriously, we’d sit around and talk that up to the nth degree. Being as young as I was, it was exciting and a path for me to escape my situation at home with my family, God bless them. So, yeah, change the world while we’re at it! The music we were developing was very well-rounded: R&R, Hard Rock, Folk, the beginnings of Texas Punk, Blues, Jazz, with a little Country & Western to round out the edges. Extremely eclectic. Had we continued, I think the compositions would have been killer.

Paul: Well, to be Rock & Roll Gods, obviously! Beyond that, for me, it was the chance to be part of something creative, stimulating, intense, awesome, expressive, incredibly freeing, and some of the most fun I have ever had.

Did you try to land a deal or attract management back then, or did you all just stay in the trenches, doing it the hard way?

George: We had the record deal with the Barons. Sadly, we weren’t together long enough to reach a level of popularity that would have required professional management. Paul Eakin did a fine job of protecting our interests.

Tim: Through George and Paul, a contract was conceived and signed with the Barons out of Rosenberg, Texas, a Czech polka band that made it big in the mid-South Texas region. They knew that we needed to perform on stage.

Paul: Please see the next answer.

What was the reason behind releasing your album privately? How many copies did you press, and where’d you take it to get it done? Or am I wrong here and Baron Records was a real label? Please elaborate.

George: Baron Records, while not well-known, was a real label. I believe the initial pressing consisted of 500 albums, but that may be wrong.

Tim: Paul and George can explain the particulars on this subject. It made sense to release the album locally, distribute as far as they would press records. Yes, Baron Records was a real label. We cut the album at the Barons’ studio in Rosenberg, Texas. We would often arrive to find that the board broke down again, delaying recording. A great experience. I think it is fair to say that they did not know how to produce a rock band; that wasn’t their groove. So a great deal of the production and direction came through us as the members of STUD during the track recordings and mix-downs. We were full of ideas and optimistic enough to believe in the project.

Paul: Yes, Baron Records was a real label. The Barons had a good organization, a band with great equipment, their own recording studio, booking and management people, and all the connections that you get in the music business by working steady for decades. When we signed with them, it was with the understanding that we would record an album’s worth of material for them. They would have it pressed, and then they’d help us with promotion. George would know the specifics on everything if he remembers. I think they pressed 50.

Where did you sell the album—just at shows, or did you send it to labels or radio stations, hoping someone would catch on?

George: We sold a few at gigs. We did take the album to KLOL-FM in Houston to see if they might give us some exposure. “Crash,” the god of the underground-sound FM DJs, appreciated our instrumentation, but wasn’t overly enamored with our vocals and said he would pass on our initial effort.

Tim: Sent to other labels and to radio stations. We met with a Houstonian radio DJ, “Crash,” to promote the album at the old KLOL 101.3. He was as much a musical influence as his name suggests. But it was great to go into that radio station. We sold to anyone we could, but we relied on the Barons to come through to distribute and market the album.

Paul: We used them for promotion. Sent copies to the rock stations in the area.

Did you get any press locally? Or was it all a bit of the wild west, flying under the radar?

George: We received a few lines occasionally in the Rosenberg and Needville newspapers, but not in Houston. Again, STUD was still growing as a band and simply had not been together long enough at the time we broke up to make any waves.

Tim: That’s an interesting way to put it, “Wild West”! I mean, I think we were ready to market ourselves to booking agents and other people who were managing live talent for venues. We learned cover songs, which really tightened up our sound. We would record it at the Barons’ studio, and I thought the sound was really good. We did try to get our name out there to the public any way that we could.

Paul: Definitely the wild west. I don’t think we ever got any press.

Now, let’s talk about the album. What moments stand out for you from working on those songs? Any track you’d like to give us a little behind-the-scenes commentary on?

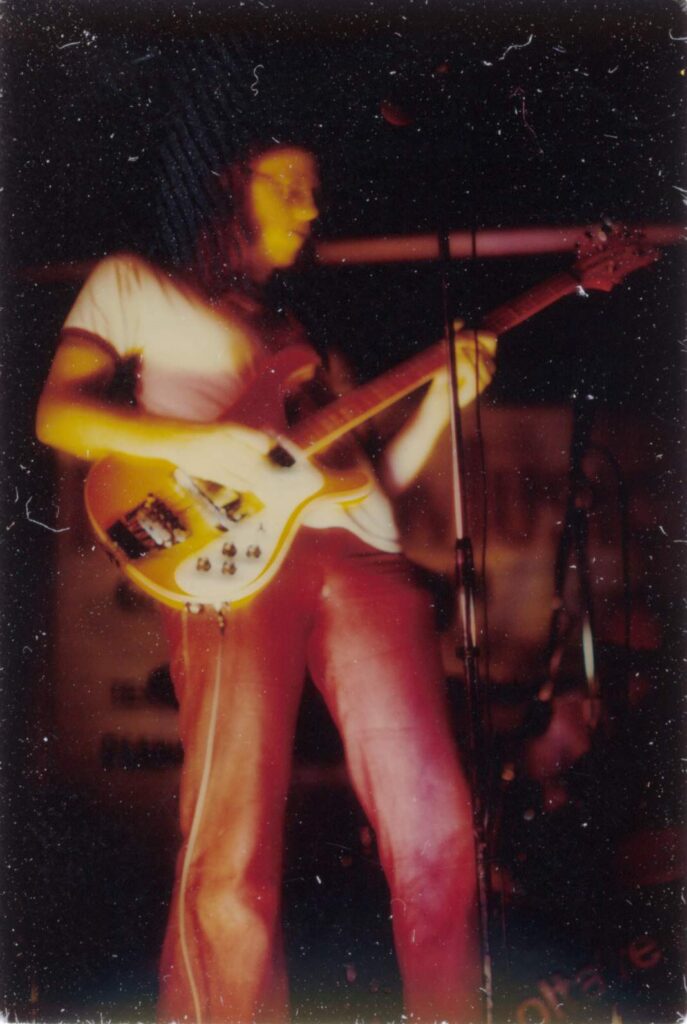

George: I vividly recall, at the Barons’ studio, the first time I could sit back and listen to Tim’s outstanding lead guitar work over a nice pair of JBL speakers. More than simply interesting, his leads were truly inspiring. Paul Eakin’s bass work impressed me as well, especially considering that bass guitar wasn’t what he felt most comfortable with. I understood that Paul was more of a rhythm guitarist and an accomplished writer, as evidenced by his masterpiece, ‘The War Song.’ To me, ‘Captain Boogie,’ ‘Woman Like You,’ ‘Jim/Blues,’ and ‘The War Song’ were the high points of our album. Those are some pretty good songs.

Tim: It was fun to work with George and Paul. THEY went pretty crazy with the vocals on the instrumental STUD, haha. I got to do a lot of guitar overlays and harmonies, a lot of fun. ‘Captain Boogie’ was to be our hit being promoted. By the way, the woman saying “Come on boys, do it again” is my wife. So really great things came out of the entire experience. It really makes you focus on improving when you record and listen to the playback of yourself.

Paul: The first day we were in the studio, George was working on the drum set and testing things out, and the engineer was getting the sound roughed in. The way things were set up then, they couldn’t see each other. He asked George to play his kick and then add the rest of the kit in. A few seconds into this, the engineer was very confused. George’s foot is so fast that the guy thought he must have a double kick set, and he couldn’t find the other mic.

On the song Stud, it was basically just a warm-up riff that Tim had come up with, and he added structure to it as it evolved into a song. The first layer of the song — drums, bass, and guitar — are all played live with us all where we can see each other. We never came up with a set ending, so we are all watching each other, trying to telepathically figure out what the other two players want to do, and it just worked. Somehow, Tim was able to layer two more guitar tracks on top of his original. I was in awe. Then we added the vocals, which were also done in one take, just playing off each other. About nine minutes into that track, you can hear a cricket. That’s me. My version of whistling when I’m nervous.

What was the recording process like? Did things go smoothly, or did it end up being more like wrestling a tornado?

George: Things went rather smoothly. Of course, there are always a few hiccups in the process of creating an album. I never felt totally satisfied with the recorded sound of the drums, but in looking back, I wasn’t totally satisfied with my drumming either. I’m a better drummer today, at the age of 73, than I was at 23.

Tim: No, no tornados or derechos, thunderstorms or hurricanes were experienced. A lot of patience was exercised, like you do when you’re fishing and watching the end of your rod start jiggling with a fish on. That’s when the excitement begins. And it was really exciting when we nailed it. I’m sure that the Barons were thinking to themselves, “This is rock and roll?” LOL. We were loud in the studio and pretty demanding to the engineer and producer. We felt like we were the Beatles in the studio. Take, after take, after take.

Paul: We were using the Barons’ studio and its old mixing console and funky 8-track tape recorder. They were good in their day but were getting finicky. After we were done, they planned to put in a new mixer and 24-track Scully recorder, and the poor engineer was just trying to keep everything running long enough to get our project done. We’d show up for a session, only to find out that the recorder wasn’t working or part of the mixer was dead. It was annoying as hell, but it wasn’t anybody’s fault, and there wasn’t anything we could do about it, so you’d reschedule the session and go home.

Mixing was definitely wrestling a tornado. On ‘The War Song,’ it had so many different parts, speeds, and instruments going on for over thirteen minutes that we all had to help mix.

What gear were you using back then? Was there a piece of equipment that made you feel like you were channeling something otherworldly, or was it just a mix of luck and chaos?

George: As previously stated, I played red sparkle Ludwigs with wood shells. They sported a 22-inch bass, a single mounted 14-inch tom, a 16-inch floor tom, Ludwig hardware, a Speed King Pedal, and Zildjian cymbals.

Tim: Gibson Les Paul Custom Black Beauty fretless wonder — I still own that and never take it on any present-day gigs. It’s too valuable. Also, an Alvarez-Yairi Custom acoustic that was a damned good copy of a Martin D-28. This guitar was stolen at a recording/teaching studio I worked at. Amp: Peavey Tweed 4×10 speakers tweed with 100 watts into 4 ohms. Loud. Heavy. I carried this same amp while I was a traveling and studio musician, and no joke, it weighed 45-50 lbs (20.4-22.7 kg). Pedals were simple: Cry Baby Wah, a phase shifter. I’d overdrive the amp with the Gain all the way up and the Master volume down.

Paul: I know Tim had some incredibly fine guitars that he had tweaked to the point that they practically played themselves. I had a Rickenbacker stereo-recording bass with a really nice action and, in my opinion, a great sound. George had great drums, so all the instruments were excellent. The microphones in the studio were world-class for the time. Even the mixer and tape deck were good when they worked, and we got them to work long enough to make the album. So a lot of luck and chaos thrown in, too.

So, when the record finally dropped, what was that moment like? Did it feel like a triumph or a quiet sigh into the void?

George: More like a triumph, for sure. Regarding our desire to make some kind of impact with our songs, it represented a serious move in the right direction.

Tim: It was a blessed moment that I could take into the rest of my life. It helped me perform with other national artists and record labels, I’m happy to say.

Paul: I don’t think anyone could listen to our album and think it is a quiet sigh. It felt pretty triumphant!

What’s the craziest gig you’ve ever played? The kind where everything went off the rails but somehow still felt like a win?

George: I’m not trying to be evasive, but I don’t recall any of our gigs feeling like everything went off the rails.

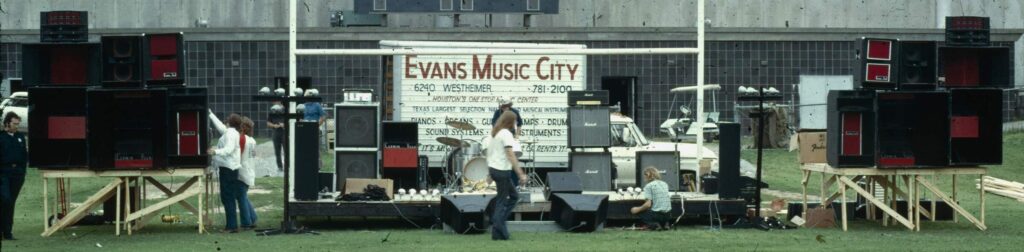

Tim: A Sunday multi-band gig in a Houston, Texas high school football stadium. STUD, Paul, had rented the entire P.A. system, which was great except expensive. I’m not sure Paul ever recouped his money. I feel badly about that. And it began to rain, just enough to make it wet and sticky. Damn.

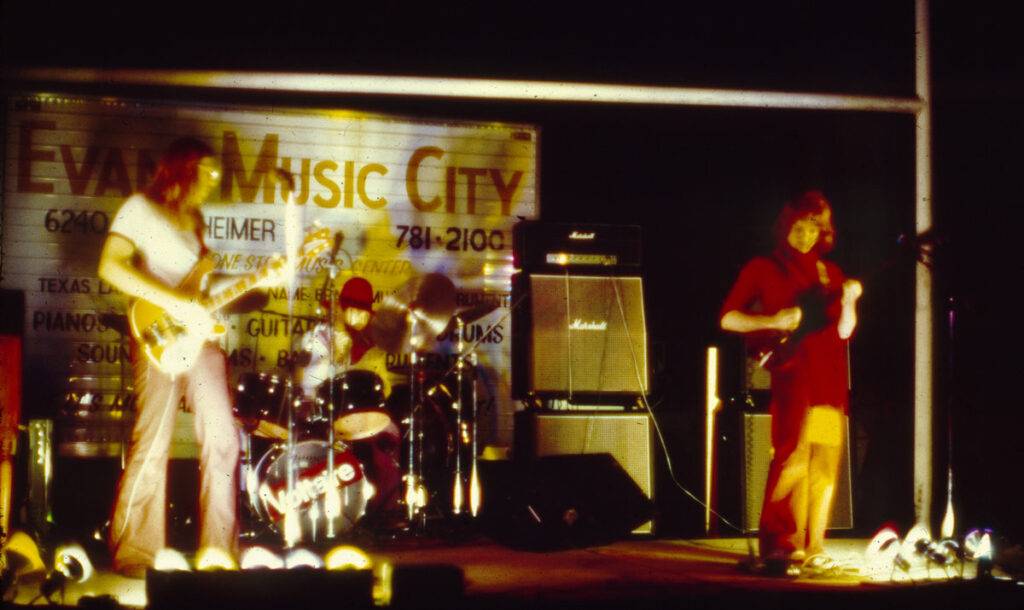

Paul: Craziest gig was one I instigated. Decided to get a bunch of local bands together to play a concert for charity. Rented a football stadium. Rented a large sound system. It was the same one Led Zeppelin used the first time they came to Houston, so I thought it would do. Put ads in the paper and even got some blurbs on TV. Day of the concert it rained in the morning, so it was nice and extra humid. We somehow got eight bands on and off and finished the evening with our set. We had a few hundred people pay to come in. It was crazy and over the top, but it felt like a stadium concert, so it was awesome. Most of the pictures on our album sleeve are from that concert.

And on the flip side, what was the best gig you ever played? The one where everything just clicked, and you felt like you were doing exactly what you were supposed to do?

George: The Delmar Stadium gig, which was Paul’s baby, felt pretty marvelous. Paul did everything he could to promote STUD. I’ve always admired him for that.

Tim: For me, we played a gig somewhere southwest of Houston, outside of course. It was arranged for by our good friend Andrew, who I miss very much. It was a diverse ’70s crowd, so we needed to not just play Rock, but tinge it with R&B. I wish we knew more, but we tried our best and I believe we delivered.

How long did Stud stick around? When exactly did you guys form, and when did it all unravel?

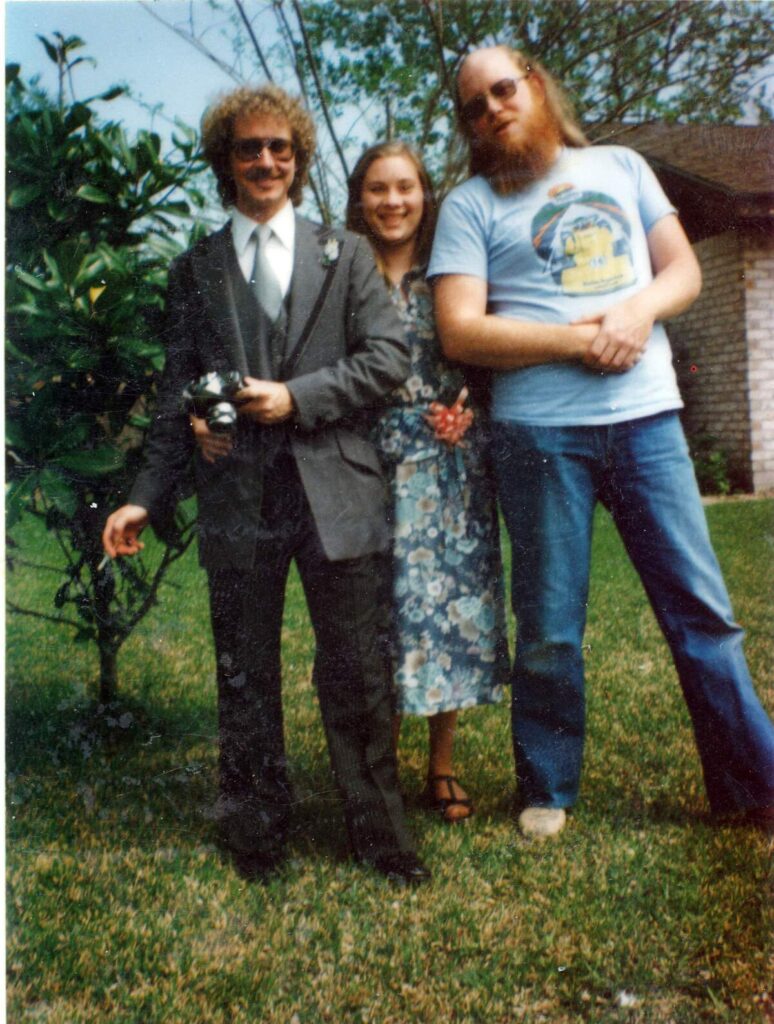

George: STUD formed in late ’73 and disbanded in late ’75. As I understood it, Tim wanted more than what STUD provided: more variety, more money, and much more devotion to being professional musicians. Since I was married and had dedicated myself to pursuing a career in broadcasting, I grudgingly understood, but the breakup hurt. I thought we were on the brink of becoming a more popular and more successful act. Perhaps the worst part of it for me was that the breakup occurred while I was in the hospital with pneumonia.

Tim: I’m happily married and had, and have, a very understanding partner in life. She knew I needed to do the thing I had trained my life for, performing the guitar. In 1976, a road band called One Day Tomorrow needed a guitarist and so I took the opportunity to make music with a new group of people and learn other forms of musical expression: R&B, funk, Jazz, Standards, along with R&R. I don’t think we unraveled as much as we each had responsibilities in our lives to ourselves and others. It is a gas that after many years our album is still getting attention.

Paul: Stud stuck around until after the album was pressed. By that time, our contract was running out with the Barons, and Tim had decided to get married and move on. I ended up running sound for another band and going on the road. George had his DJ gig and was already happily married. We are still friends, but it was like STUD was this intense part of our life that, while amazing, was not destined to be a major part of our lives. Which is why I love that the album is being talked about more today than it ever was fifty years ago.

What happened to everyone after the band? Did any of you stay in music in some form, or did life pull you in other directions?

George: I continued to play drums and worked in radio until 1980, when I took a job in sales and customer service management for Warner Cable TV. Paul became a sound tech for some fine bands. Tim continued to perform and is currently playing in a fine band called Analog.

Tim: I went on the road pretty much straight out of high school. I wanted to go to the premier regional music and Jazz university in this region of the U.S., now known as the University of North Texas near Dallas. Dad offered a take-it-or-leave-it deal to stay and attend school at the University of Houston to save him money. It was a generous offer; I just couldn’t or didn’t see it as such and had the hotcakes to hit the road. Those were hard times. I played steady with several bands while based out of Dallas, Texas. These bands were club and hotel bar bands that were my night-time job and I supplemented with playing some studio musician gigs and non-skilled jobs. Studio musician work is really great – it demands discipline and woodshedding with your instrument. Lots of fun. Through a series of life events, I eventually went to university to become an occupational therapist, which is what I’ve done for the rest of my life. I am blessed and fulfilled.

Paul: I worked sound with a regional band for over thirty years. The ears started going, so I had to retire from music.

What’s keeping you busy these days? Are you still living the dream, or have you traded in your instrument for something else entirely?

George: Being retired, I watch TV and spend a couple of hours daily playing on a marvelous virtual drum set made by Roland.

Tim: I’m semi-retired, working more as a musician on weekends with my band, Analog. I also have been in hospital management, and I work as a healthcare rehabilitation facility surveyor for accreditations. Oh, and twin grandsons.

Paul: I’m living the dream! It’s just a different dream with a wonderful family, and two grandsons that keep me busy. I still play guitar, but just for me.

Are you excited about another Guerssen reissue? Does it feel like the music is still alive, or is it more of a time capsule at this point?

George: I am excited any time I hear that our album continues to draw interest. It truly feels as if the music is still alive, and as I listen to the songs, I have to say we were on the right track. There is some very good stuff on that album.

Tim: Always excited about the efforts that Guerssen has done with STUD. We’re honored and very happy to be recognized.

Paul: After this long, any album you are part of is going to feel like a time capsule of memories to you. Hearing it brings back so many dreams and emotions. However, I believe the car full of people who were staring at me the other day when I had the Stud album cranked in my car while I sang harmony with myself would probably say it feels alive to them. I know it certainly does for me.

Looking back, what’s the highlight of your time in Stud? Which songs are you most proud of? And which gig left a lasting impression on you?

George: Recording the STUD album still reigns supreme as my favorite moment with the band. Woman Like You sounded exactly like what I had envisioned: proud, virile, powerful, and beautiful. Doctor T, that’s Tim Williams, blew us all away with his lead on that one. Captain Boogie is an iconic tune; real rock and roll, with another infectious lead by Tim. Jim/Blues is one of those grind-it-out blues and rock tunes that any good rock and roll band has to possess in their repertoire. Then there is The War Song, a powerful and psychologically deep tune, written by our bass player, Paul Eakin.

Tim: Fortunately, Paul and I were able to bring some musical experience into the band where, let’s face it, George had the smarts. His work as a radio DJ kept him informed and in tune with the music industry, especially Rock and Roll. Southeast Texas gigs were all good to us, and we were well received. I’m most proud of the song Stud, just developed that riff on the low E string and rolled with it.

Paul: Stud was my introduction into the music world. It was a crash course on everything having to do with a real band: writing as a group, practicing efficiently and not just jamming, developing a sound and style for your instrument that helps you stand out, good techniques for recording, playing together live in front of people, everything. The biggest thing I learned? Work with great people and you can make magic.

George was our leader, confident, easy-going, everybody’s friend. Super focused on his writing and drumming, but just so happy to be playing. George radiated passion and joy for his music. He still does. He sends me recordings of himself playing along with different songs all the time. The man can still play.

Tim was our prodigy, the youngest of us, quiet and unassuming. He could pick up any guitar and draw a crowd very quickly. He was an incredible musician, which meant he could play just about anything we needed. It also meant he was always in the spotlight, always under pressure. Yet he handled it all with a maturity that made him seem wise beyond his years.

I was the guy just happy to be along for the ride. I didn’t read music or care about music theory. I was a converted lead guitarist who kept trying to play lead bass. By the time we started recording the album, I was sure we were going to be rock stars. Hey, what’s the point of trying if you don’t believe it’s possible? I was very proud of the whole album, and I’m still shocked that it was me playing. I think the best I played bass was on Woman Like You. It’s a really powerful song, and I felt like I did it justice. But then I’m also very proud of the way The War Song turned out, since the engineer couldn’t know for sure if he was punching in on a track properly because of the equipment. I had to play and sing all the way through perfectly, or we had to start over from the beginning.

Tim: Paul is being very kind, those are nice words, bruh.

Paul: Tim, I’m just calling it the way I see it, or in this case, hear it. Haha.

s there any unreleased Stud material we should know about? Or is it all buried and left to the winds of time?

George: I keep hinting to Tim and Paul that we could do a couple of new tunes via file sharing, especially since this is our 50th anniversary. Who knows what the future may hold?

Tim: Yes, there are a couple of songs from that era I developed in studios over the years. One is called ‘Please Come Home,’ recorded with Paul’s help in Houston, sans drums, it was just a demo, and another called ‘Dreamer,’ recorded in Dallas. George had a song started, with a funky beat, that I think was called ‘Lemon Song.’ I’ve developed music from my home studio over the years, but never published. It needs a STUD type of band to bring it together.

Paul: There are no unreleased, original, Stud songs. We had written a few more, but they were never recorded. I have two or three copy songs from a booking tape I found, but that’s it.

Thanks so much for taking the time to do this! Feel free to say whatever’s on your mind for the last word. The floor’s yours.

George: Stud was still in its infancy when it came apart. The band was beginning to fine-tune our unique sound. I have no doubt it would have become something that would have led to bigger and better things. Woulda, coulda, shoulda, but didn’t. Still, what we did was intriguing. It had to be, or it wouldn’t still generate interest 50 years later. Thanks to Paul and Tim for helping to make one of my life’s biggest dreams come true.

Tim: I had a great time remembering and reminiscing. Thanks so much.

Paul: This was a great experience! I remembered quite a few new things, thanks to the way you asked your questions. Things I hadn’t thought about in literally fifty years. That was an unexpected gift. Thank you!

Klemen Breznikar

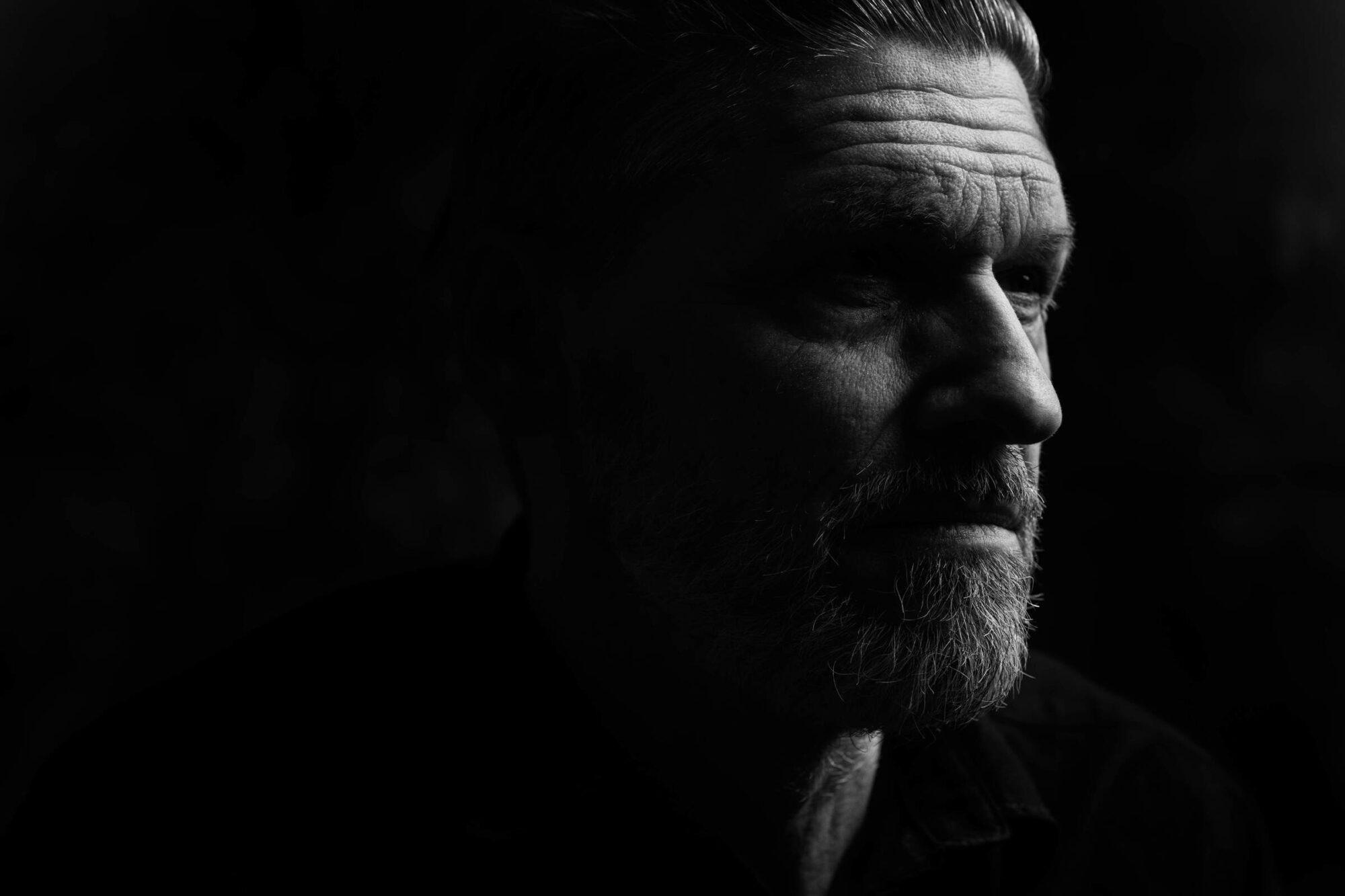

Headline photo: Stud (Credit: Band)