Deerhoof’s Greg Saunier Joins Forces with Yea Big’s Stefen Robinson on ‘No Timing’

‘No Timing,’ the collaborative album from Stefen Robinson (Yea Big) and Greg Saunier (Deerhoof), feels like a living act of meditation.

Conceived as a reverent dialogue with Jim O’Rourke’s ‘Bad Timing,’ the record dissolves the boundaries between homage and experimentation, structure and surrender. Robinson’s looping bass clarinet, gamelan, and double bass form a patient architecture; Saunier’s piano enters like thought itself. Very restless, searching, interrupting and completing the silence in equal measure.

What unfolds is an experiment in coexistence, not improvisation in the conventional sense. The two artists seem to enact opposing forces: one striving for stillness, the other delighting in motion. The result is hypnotic… a sonic koan about attention, ego, and time.

At moments, ‘No Timing’ recalls the elemental calm of Harold Budd or the suspended grace of Morton Feldman, yet it remains unmistakably of our anxious century. Ultimately, ‘No Timing’ is a meditation scored for two minds learning to breathe together, and, as its title suggests, it is timeless in sound.

“I love playing against things.”

‘No Timing’ is a direct meditation on Jim O’Rourke’s Bad Timing. What is the spiritual architecture of Bad Timing that you sought to inhabit and expand upon, rather than simply deconstruct? How does this process — reverence through reinterpretation — connect to the “meta-cognitive and spiritual revolution” that is a primary focus of your work, Stefen?

Stefen Robinson: I love this question, Klemen; it cuts straight to the heart of things for me. The “spiritual revolution” I’m attempting to contribute to is one in which deeper understandings of the “self,” the interconnectedness of everything, the oneness of everything, etc., are viscerally understood and lived. I believe humans are capable of living together peacefully and sustainably, and within political-economic structures that truly work toward decreasing unnecessary suffering, not only for our species but all life. Any political-economic revolutionary struggle without a genuine “spiritual” or “meta-cognitive” revolution going on side by side will not end in peace.

What does this have to do with our music? Well, for me, along with meditation, music has always been one of the primary ways I’ve been able to experience the possibilities of radical meta-cognition and getting in touch with whatever it is we are all a part of, realizing the large “self,” so to speak. Music, both as a listener and a performer, as a composer and student, has been for me, perhaps, the most direct path toward cognitive liberation. Hopefully this is making some sense.

And much of Jim O’Rourke’s music has been a catalyst for me to go deeper into my own mind, heart, and self. I first heard Bad Timing in my late teen years, a very formative time in my life. Bad Timing did things I dreamed about. O’Rourke’s record sounded to me like it came directly out of my own consciousness. The first time I heard it, it was a revelatory experience. I felt connected to the sound in ways difficult to describe with language.

If possible, I want to make music that helps do that for others, music that can point the way toward something ineffable that unites us all. So, making ‘No Timing’ is both an attempt to pay homage to the experiences Bad Timing offered me and also to create a new sonic environment in which those experiences are possible for others. I hope this doesn’t sound like a bunch of nonsense. Music, revolution, the “self,” meditation, interdependence, liberation, and decreasing suffering are all a part of the same functioning whole for me.

Greg, you state you weren’t familiar with the O’Rourke record but were drawn to the project by Stefen’s bass clarinet playing. Can you describe what it was about his playing that first struck you? Was there a specific moment, or perhaps a quality, that suggested an improvisational dialogue with your own spontaneous, intrusive thoughts?

Greg Saunier: Yeah, I’ve never heard that record. I’ve been out to dinner with Jim though, and he is very funny. He has great stories of all the people he’s worked with. It’s possible that Stefen mentioned the record when he proposed the collab, and I missed it. It was a cold DM. But I went and listened to some of Stefen’s stuff on Bandcamp and just said yes. Bass clarinet is my favorite instrument, so he already had me there. And it seemed like it would be improv. I was actually surprised when I got this very layered, repeating track. It was a great challenge, and I loved it.

Stefen, you mentioned hearing Deerhoof around the same time you first heard Bad Timing. What was it about Deerhoof’s music that resonated with you in a similar way to O’Rourke’s, as something that “came directly out of [your] own imagination”?

Stefen: Oh wow, this is difficult to put into words. The first Deerhoof album I heard was ‘Apple O’.’ And yeah, it was actually a couple of years after I heard ‘Bad Timing’, but within the same extremely formative years. The sound of ‘Apple O” just blew me away. The beauty and intensity of ‘Apple Bomb’ still, to this day, bring tears to my eyes. The entire record is incredible. And then I learned more about Deerhoof and how they made their records in their own ways, super DIY. That’s what I was always doing, or trying to do. Not only their music, but also their approach to making it, really resonated with me. I was making music with whatever gear I had accessible to me, and I thought, “If Deerhoof records can sound so alive and vibrant and full of energy and creativity, so can mine. I just need to keep doing it and figure it out as I go.” I think Greg recognized that about my recordings when he first heard my work.

In the many years since I first heard ‘Apple O’,’ I’ve obviously enjoyed Deerhoof’s entire catalogue. Every album is a banger. Honestly, I was a little taken aback when Greg said he was down to make music with me. I’m not trying to pander; Greg is a hero of mine. It’s really exciting to me that we’re making music together.

Greg: That’s so kind, Stefen! Thank you.

‘Bad Timing’ is noted for its use of “traditional instrumentation” like acoustic guitar, piano, and brass, blended with more experimental textures. No Timing also features a blend of instrumentation, from bass clarinet and double bass to gamelan. How did you navigate the choice between honoring O’Rourke’s sonic palette and introducing your own?

Stefen: I suppose, for me, the specifics of the sonic palette weren’t very important. What matters most is what we do with the palette available. That said, at the time we were working on this music, I was really enjoying playing percussion, the gamelan strips that were gifted to me, a really warped electric guitar that I traded a bonsai tree for, and trying to play all these instruments in repetitive, meditative ways. Like playing the same double bass line over and over again. It was a challenge to myself to try to play the same lines repeatedly and get really engrossed in the sound without totally screwing up the line.

I didn’t want to just do a cover version of ‘Bad Timing,’ you know. I wanted to borrow a line from ‘Bad Timing’ and make something totally new while honoring the spirit of the original album. And I wanted to do it in a way that created space for Greg and me to share this musical conversation. Hopefully we achieved that. I also thought it was perfect that Greg had never heard the O’Rourke album, as his take on the music would be totally fresh. Greg was able to come at this with a true beginner’s mind, which made the whole thing work.

Greg: The gamelan is what stuck out to me first. Not just the instrument, but the idea of the bass part going slower than the higher parts. And the hypnotic repetition. Of course, gamelan is not “experimental” to an Indonesian person. But I agree with Stefen. I didn’t feel like it was important to be reverent to any specific artist or tradition. Even Stefen! I didn’t feel like I needed to be reverent to him either.

Greg, you describe your contributions as “spontaneous intrusive thoughts, always related in some way, but also attempting to tug the music away from its contemplative character.” This is a fascinating concept. Can you elaborate on the mental and musical state required to be simultaneously related to a piece of music while also trying to pull it in a new direction? How did you know when to push and when to pull back?

Greg: Haha, well, it’s the nature of DIY PR that the band has to come up with descriptions of their own work. I, of course, was not thinking anything of the kind when I started playing along with Stefen’s track. This description is an after-the-fact rationalization of why on Earth I played what I did. I don’t have the slightest idea. But that’s the fun of improvisation — you surprise even yourself. I had no desire to do violence to Stefen’s thing, or O’Rourke’s. But I also demanded of myself that I find a way to still exist within it. It would have been easy to try and play an entirely supportive role. I mean, what Stefen sent already sounded like a finished record to me. So I was having a conversation with myself on the piano. Everything was “Yes, but…” Which was funny because he couldn’t react to me, as his part was already done. So it was this attempt to sustain my insistence that I find some way of fitting without disappearing.

Stefen, you are a Soto Zen Buddhist, and Greg, you speak of trying zazen but being unable to “sit still.” This seems to be at the heart of the album’s dynamic tension. Did the process of creating No Timing offer any new insights into the “definition of meditation” that you were investigating?

Stefen: I don’t know if I gained any new insights about meditative practice from making this record, but making this music was very affirming, for sure. As I kind of started to get at in the previous question, my meditative practice deeply informed my playing on this record. And the way Greg describes his playing as “intrusive thoughts” is so great. I love that way of hearing what he did. I’ve been practicing zazen for quite a long time now, and the way his piano playing “intrudes” is really quite similar to the way the mind experiences itself during meditation. That dynamic tension, as you called it, Klemen, really wasn’t something we planned to explore when we set out to make this record; it just happened that way. We didn’t, for example, discuss meditation or revolution or anything like that before we started making this music. But our personal experiences with these practices and ideas so clearly come through in the music, it’s fairly remarkable, in my opinion. It’s almost as though I tried to do everything I could to create an environment in which Greg could sit still, and he came into that environment and did everything except sit still. It’s so fun.

Greg: Honestly, it was a total privilege. I love playing against things. Trying to create friction and resistance without just wrecking everything.

The phrase ‘No Timing’ itself carries a dual meaning — the absence of a fixed rhythm, but also the idea of being beyond the confines of time. Did this dual meaning inform the compositional process for the album? Did the act of expanding a theme from a 1997 album feel like an act of escaping time itself?

Stefen: This is another difficult question to answer. First, I’m not convinced that linear time is anything more than a naturally selected delusion. I mean, yes, time is real in the sense that we perceive existence in a way where the emergent concept we call time is something we use to structure our days. But outside of time being a cultural emergent concept, it seems increasingly clear that the universe doesn’t operate according to linear time in the way we feel it does. I think about this a lot more than I should.

You’re correct about the title having multiple meanings, but I hadn’t really even thought about our work here expanding or escaping the being-time of O’Rourke’s piece. I really like that idea. Thanks for that! I’m not sure how these ideas about time informed the music on the album; no doubt they did, I’m just not sure if I could explain it.

Greg: I liked playing things that were in irregular time against what was very regular. Not just the pulse but also the phrase lengths. Or I would try an idea and sometimes stick with it for a long time and sometimes abandon it quickly.

With the world in constant flux, is the concept of “peaceful revolution” more or less urgent today? Does music play a different role in this revolution now than it did when you started Yea Big in 2006?

Stefen: Revolution and peace are just as urgent now as they’ve ever been. Sometimes things seem more dire and more urgent now simply because we’re living through it now. But I believe peace was equally urgent in all previous eras or epochs. That said, as we witness the genocide we’re doing to Palestinians, as one of the most egregious examples, knowing the US government is funding and supporting it, knowing my tax dollars are materially aiding the genocide, I feel an extreme sense of urgency to do everything within my power to stop the madness. And sometimes it feels utterly hopeless. Especially when I genuinely believe that the only path to peace is peace itself, and how impossible that seems at this present time in world history. I do believe that I am more conscious today than I was in 2006 about making music that can help manifest peace in this insane world. So in that sense, yes, my music is playing a more intentional role than I believe it was in 2006. Is the music we make having any positive impact on the world? I have no idea. But we have to try.

Greg: I love that because it is true. Whether it’s peace or any other ideal, you bring it about by going ahead and doing it. And another important ideal is freedom. Improvisation is always political because it is about freedom. But it also is freedom.

Greg, as a founding member of Deerhoof for over 30 years, you’ve experienced a constantly evolving landscape in music. How does a project like ‘No Timing,’ which feels intensely collaborative, fit into your larger body of work? Does it feel like a departure or an extension?

Greg: I start everything kind of blank. So maybe that means that everything for me is a departure. Deerhoof has been lucky because our listeners seem to like the departures. They like to be surprised. It’s the biggest privilege imaginable for a musician. But while I’m actually performing the music I’m pretty hard-pressed to say what it is I’m actually doing. Certainly I feel very busy and engaged. I’m trying to think back to the moment I started recording the piano on No Timing. I just had this feeling of being inspired. Like, “I know what to do.” And then I just did it. Deep down it didn’t feel so different from how music can always feel when it’s really clicking. Something beyond happiness or sadness or anger or confusion or humor or beauty, but somehow all those things.

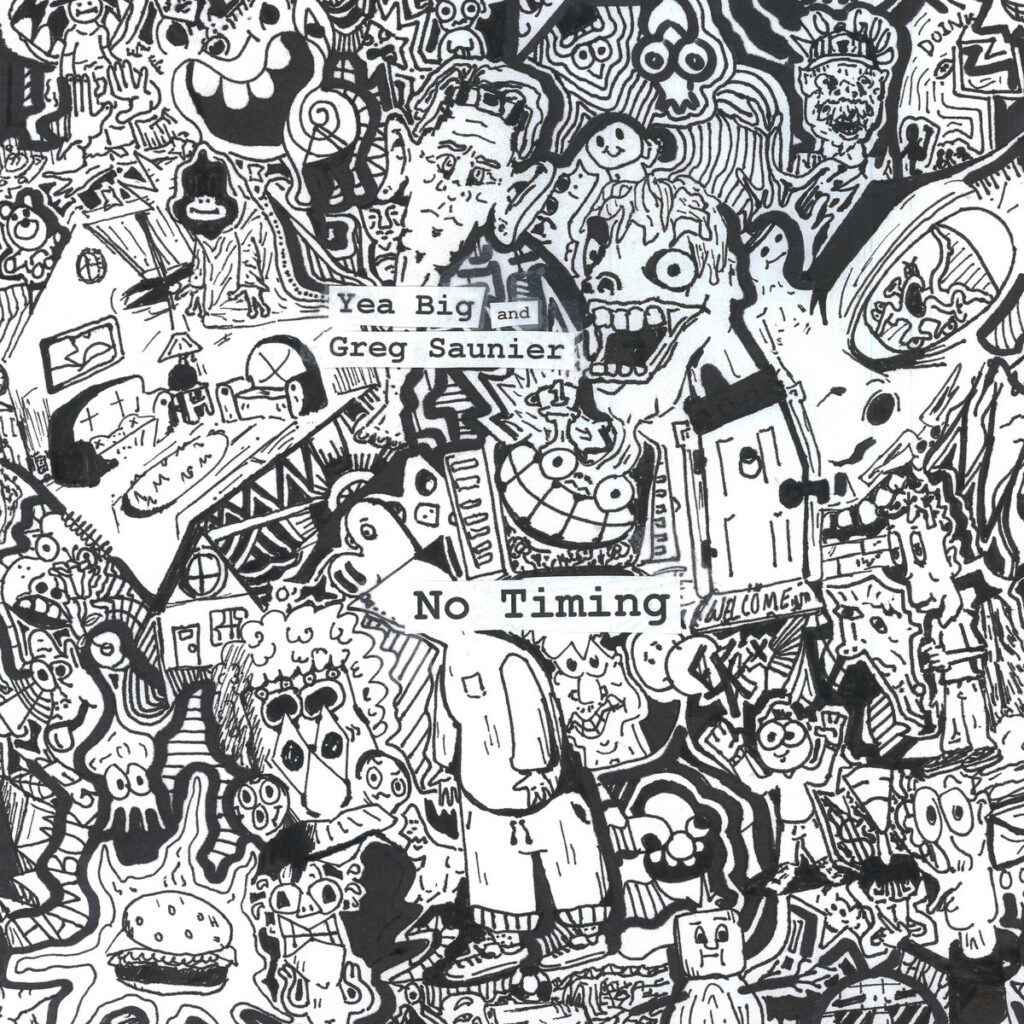

The album art is a dense, intricate black-and-white drawing. Can you tell us about the process of creating it? Is it a visual representation of the album’s themes of fragmentation and reverent interpretation?

My “day job,” as they say, is as a high school sociology and history teacher. One day I noticed one of my students drawing during class, and without even really thinking about it I asked him, “Would you ever consider making album art?” After I explained what I meant, he immediately answered, “Yeah!” There was just something about his drawings that grabbed me. I asked Luke — that’s the artist’s name — to listen to the album before he agreed to create the art. I said, “If you don’t dig the music, you shouldn’t do it.” Well, he liked the record, he created those fantastic drawings, Greg loved it as much as I did, and so that’s what became the cover. I really don’t know if anything he drew was influenced by the music in any way at all. The drawings seem to fit the music though, somehow.

Stefen, you use a diverse array of instruments, while Greg is best known for his drumming but also plays piano. For this project, Greg’s piano playing is described as “every bit as angular and expressive as his drumming.” Did the choice of instrumentation for each of you — Stefen’s layering and Greg’s piano — help define the roles you each played in the collaboration?

Stefen: Absolutely, our instruments helped define our roles, I’d agree. I think my layers are the base and Greg’s piano and drums are the superstructure. Honestly, I was shocked, in a good way, when I first heard what Greg was recording. I thought he would lean more into his drumming. I was not expecting all that piano. But I instantly fell in love with his piano playing. I originally recorded some piano myself, but I removed my piano entirely from the mix to help, as you say, define our roles. I’m really happy with what I played on this record, but Greg’s piano is really the centerpiece for me. And his drumming is like when you’re about to wake up from a wonderful sleep but you have an extra brief bonus dream. You wake up stoked and refreshed and energized.

Greg: I planned to play drums too. I thought, “I’ll just put a little piano at the beginning.” And then it kept going. It’s a Casio I have. I put it on the “mellow piano” setting. It came with a pedal originally but it’s lost, so everything is no pedal. Like Glenn Gould haha. The longer I played, the more I liked it. It seemed to both fit and not fit the track.

The collaboration is an “album-length meditation” on one of O’Rourke’s themes. Can you speak to the decision to focus on a single theme for the entire record, rather than a variety of themes? What creative opportunities did this constraint provide that a more varied approach might have lacked?

Stefen: That short repeating theme from Bad Timing is something that’s played over and over in my mind for over 25 years. I can’t explain why I’m so drawn to it. But I really just wanted to see what would happen if we created something based off of just that one theme. There are ideas and sounds that will only emerge when given enough time and space to develop. There are other parts of ‘Bad Timing’ I love equally as much, but this particular arrangement of notes just seemed conducive to re-creation. I kept thinking to myself, “What if a contemporary gamelan ensemble reimagined ‘Bad Timing’?” And this is what came out of that.

Greg: It was such a pleasure for me. Stefen left so much room. The gamelan, being made of metal, has overtones that you don’t hear with wooden instruments, certainly not on a piano. Part of the joy was interacting with those overtones. Anyway, I found Stefen’s track really very modest and generous. A red carpet. He obviously put a lot of time and work into making the track so perfect and beautiful. But it didn’t point at itself and scream, “LOOK AT ME.” So much of life in 2025 is just that. And so much incentive to engage in exactly that mindset oneself. Incentive or even imperative. So this was a privilege. Stefen didn’t demand I behave that way, so I took it as a challenge. What other way might there be to behave?

Klemen Breznikar

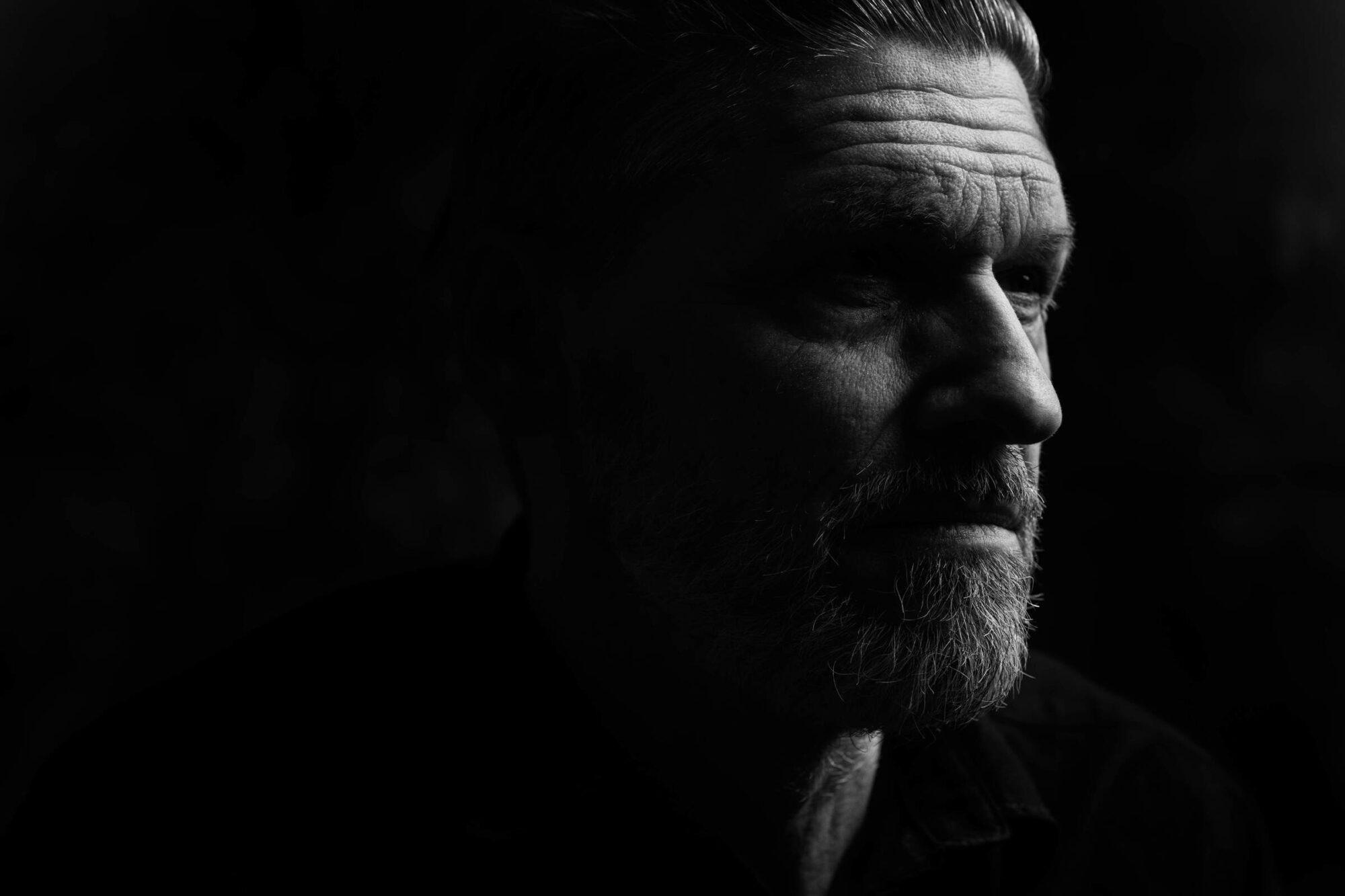

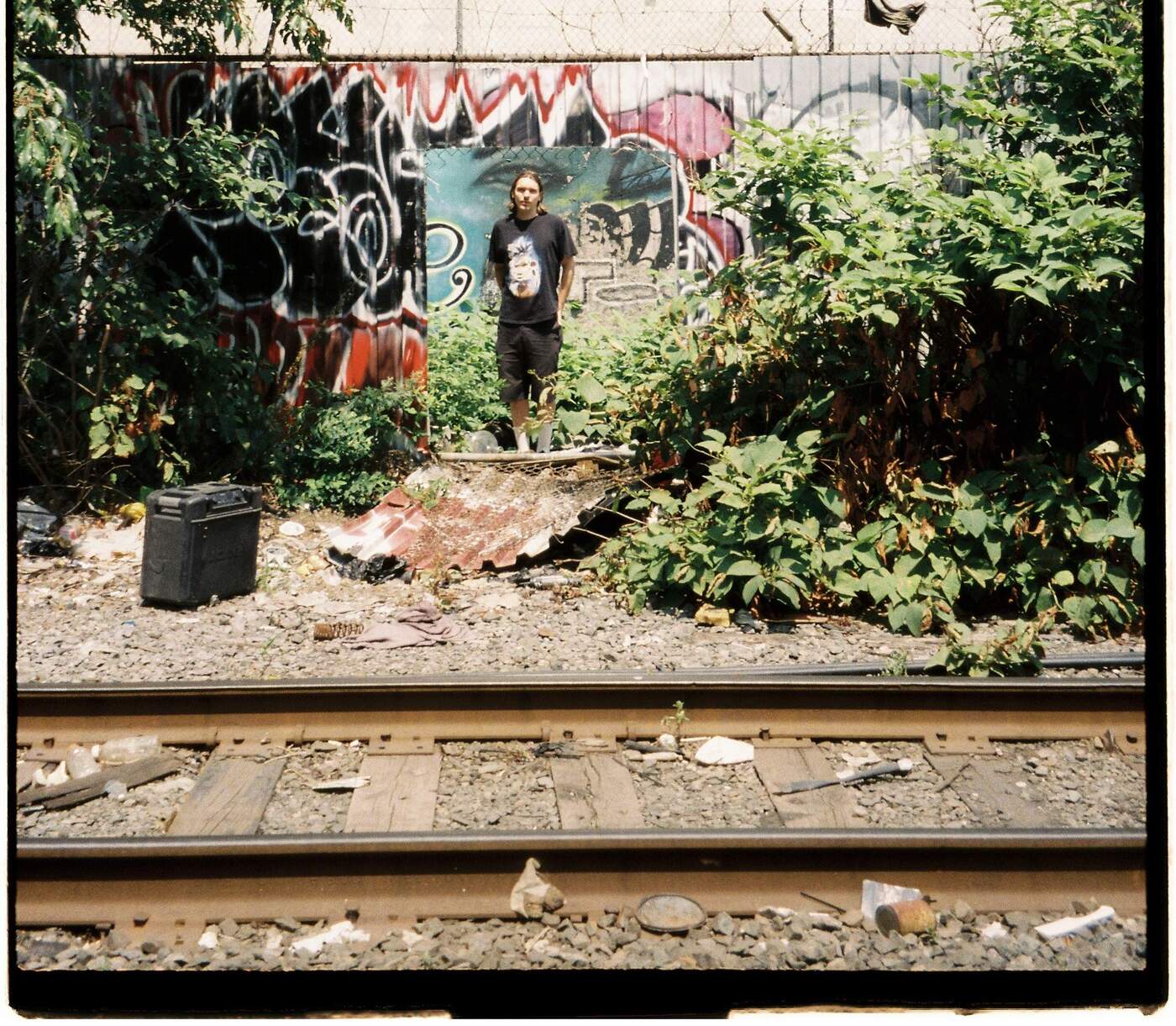

Headline photo: Stefen Robinson (Yea Big) and Greg Saunier (Deerhoof) (Credit: Jamie Breeck)

Yea Big Bandcamp

Greg Saunier Instagram