Shawn Phillips | Interview | “Better go and make the change”

Shawn Phillips never played by the rules because, quite frankly, the rules never applied to him. In an era when record labels were slapping neat little genre stickers on everything, Phillips was out there constructing his own private world—one only accessible to those willing to listen beyond the radio hits.

He didn’t just blend influences; he broke them apart, reshaped them, and let his song structures melt into something entirely his own.

He should have been a household name. But while the industry was busy trying to package artists into easily digestible brands, Phillips was making music that refused to be spoon-fed. Too progressive for folk, too intricate for rock, too cosmic for the mainstream, and too brilliant to care. He was hanging with Donovan in the late ’60s, rubbing shoulders with The Beatles, and studying sitar under Ravi Shankar—so much so that he even shared some of what he learned with George Harrison. His voice—sometimes a whisper, sometimes a gale-force storm—was an instrument in itself, bending around melodies with an elasticity few could match.

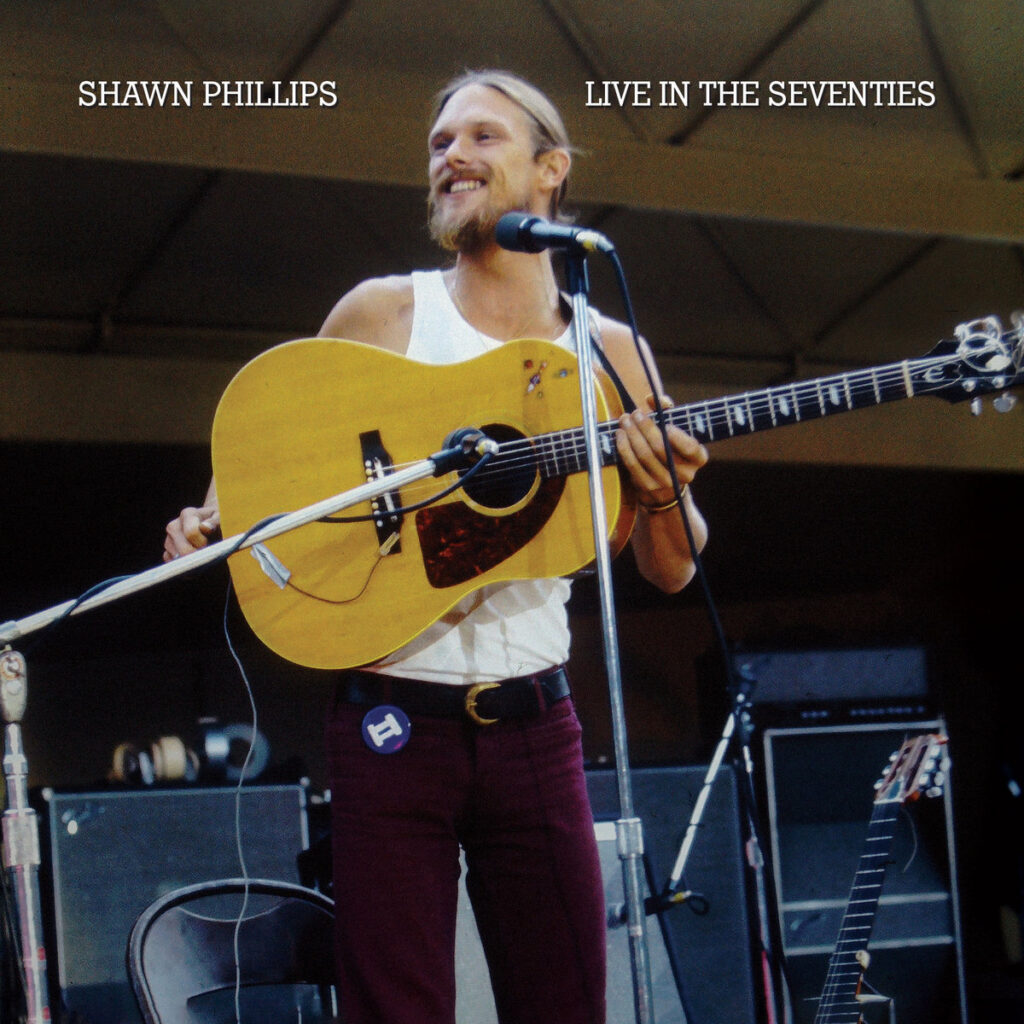

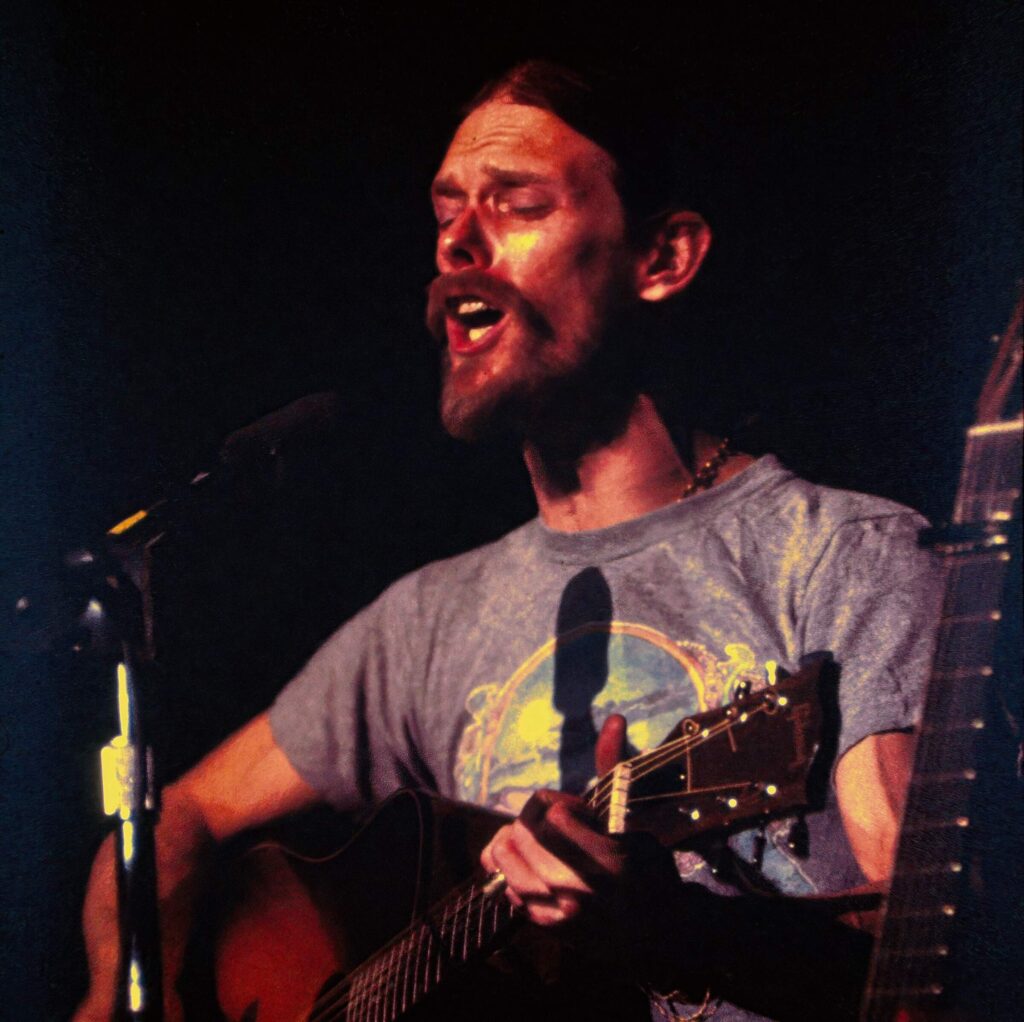

Thankfully, Think Like A Key Music is making sure the world doesn’t forget. ‘Live In The Seventies’ is a time capsule from an era when music was about exploration, a journey. The recent release of ‘Outrageous’ captures Phillips at his freewheeling best, tearing through improvisations that prove he was never just another singer-songwriter—he was a force of nature.

Oh, and by the way—February 3, 1943. Happy Birthday, Shawn.

“We were just doing what our hearts guided us to do”

It’s wonderful to have you with us. How have you been lately?

Shawn Phillips: I’m fine, thank you very much. I’m going through a tough patch with upgrading my studio because I want to do another album. I want to start working on that.

We have been really enjoying the release of ‘Outrageous’ via Think Like A Key Music. Can you share the inspiration behind this album?

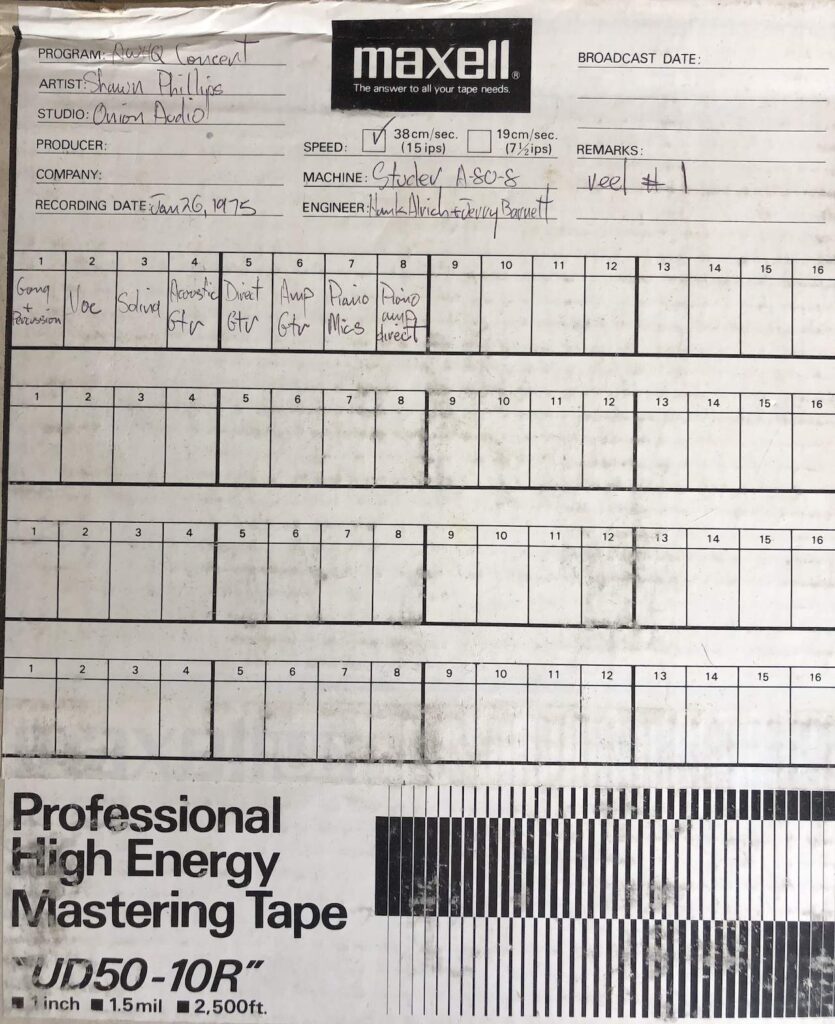

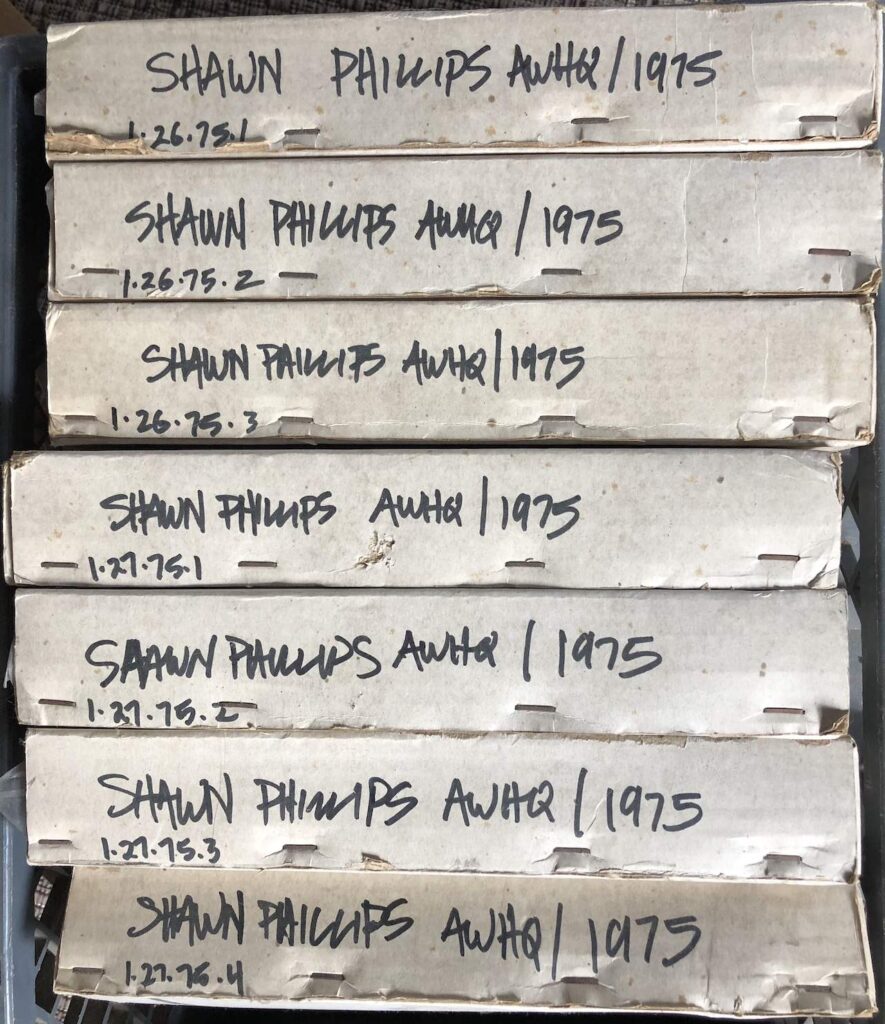

Well, actually, there was no inspiration on my part, because I was unaware that Roger at Think Like A Key Records and Alex Wroten, producer and director of a feature-length documentary to be released in the next year or so on my life and history in music, had been researching all the recordings they have found to date. I only found out when they told me they had found multiple recordings of concerts I had done during the ’70s and took 51 songs and upgraded these recordings in the studio to today’s state-of-the-art audio. I had no idea these concerts had been recorded.

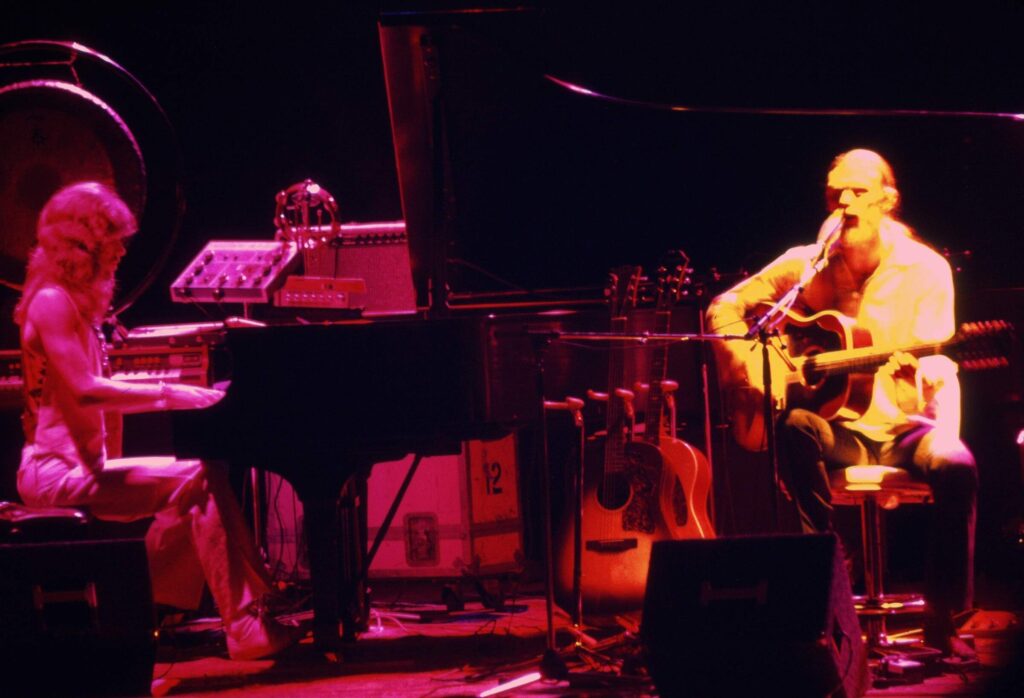

Only after this happened did they tell me that they had also found these concert recordings of J. Peter Robinson and me at the Armadillo World Headquarters in Austin, Texas.

What led you to collaborate with J. Peter Robinson on this project?

I will refer you to the statement above, but Pete and I, along with Paul Buckmaster, had been working together for several years on various albums. Pete and I toured together for almost two years.

Are there specific tracks on ‘Outrageous’ that hold special significance for you? What stories do they convey?

This is a difficult question. At 81 years old and listening back, it actually came as quite a shock to hear what I was once capable of, both playing and singing. I think the tracks that stand out for me are ‘Believe In Life,’ ‘Looking At The Angel,’ ‘Withered Roses,’ and the improvisations.

Something you should know: before every show, wherever we were playing, Pete and I—10 minutes prior to going on stage—would go out into the audience with two orchestral claves. We would walk up and down the aisles, completely silent, intermittently striking the claves. The audience had no idea what was going on. Then we would walk up onto the stage and start the show.

As for conveyance, the songs speak for themselves.

“I will not record unless all personnel are in the same room”

Having grown up in various locations around the world, how has your diverse upbringing influenced your musical style and artistic outlook?

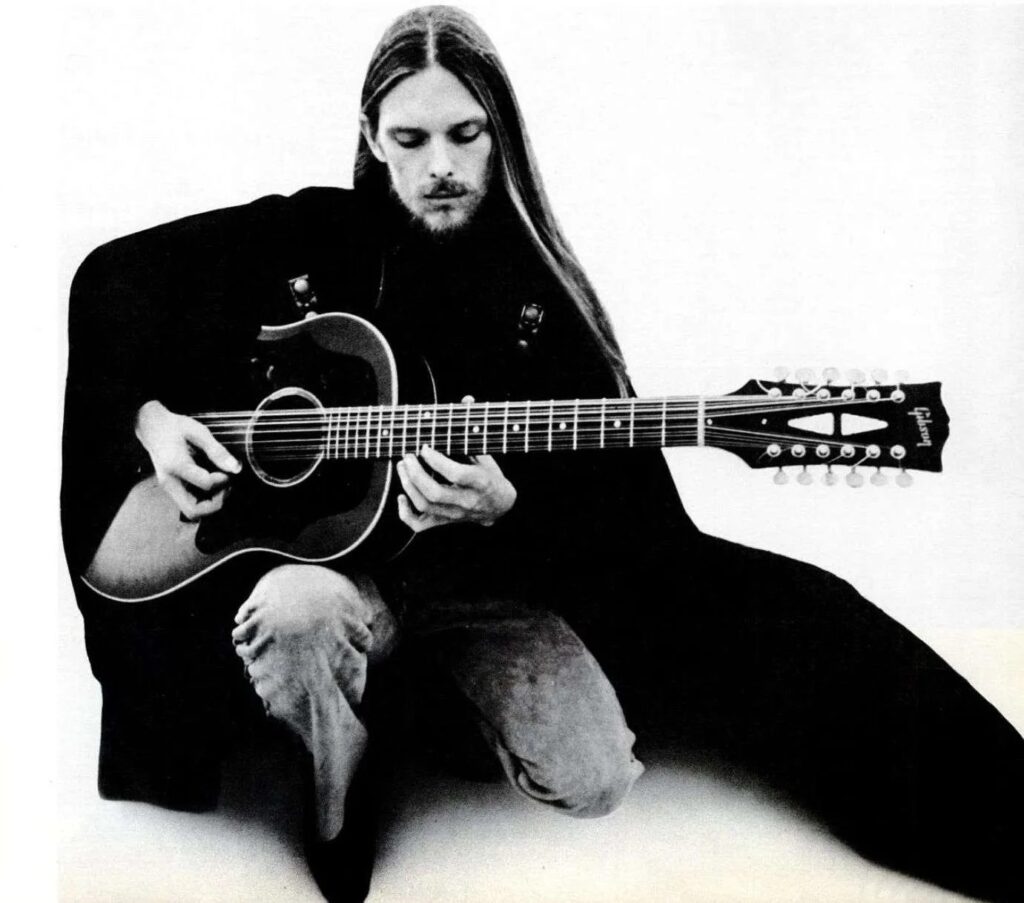

I think traveling around the world with my father, who was an author, turned me into a sponge. I absorbed so many different genres of music that I wasn’t quite sure where to turn. My father bought me a Stella guitar when I was six. Figuring out how to interpret those different genres on guitar, slowly but surely, directed me to go beyond the normal chords usually played on the guitar and create new ones. It also helped me to realize that you could fuse all those different musical genres together. And aside from that, you would be surprised when you allow the musicians in the studio with you to play whatever they feel. To this day, I will not record unless all personnel are in the same room. I tell them the basic chord structure of a piece of music is my vision. You are free to add your vision to mine. You get magic!

When it came to lyrics, it kind of boils down to this… I once wanted to tell my father a lyric I had written. I was very proud of myself, and I told him the lyric. He grabbed me by the front of my shirt and pulled me into his face and said, “Listen, punk, I have been writing for half a century and I still can’t write a better line than “Jesus wept’.” He said if you intend to write lyrics, you must have a command of the English language. Do not say “bloodbath”; say “but did the multitudinous seas incarnadine.”

This does not bode well with today’s audiences. I have had myriad fans come to me and say I had to go find a dictionary to determine what a particular word meant. This is not good for joining the top 10. Then, when you take into account that my songs are my perception of the world around me, they may become more obtuse to some according to their education. Of course, when I first started writing, I would always bow to the woman-man relationship, as most songs do, but as I evolved to writing about us as a society, I wanted people to understand that the love between two individuals is the same love we should spread among ourselves.

Who were your earliest musical influences, and in what ways did they inspire you?

I think the first thing I remember as an infant was being under the piano when my mother played ‘Malagueña.’ Traveling around the world with my father, then my grandfather—who would listen to Hank Williams—and my grandmother, who would listen to classical music, and, of course, living in Texas where I was exposed to the blues and country music, combined all of that turned me into a kind of musical schizophrenic. I’ll refer you to the above statement on what happened from there.

You performed in folk clubs alongside legends like Tim Hardin and Lenny Bruce. What was the atmosphere like in those spaces?

The atmosphere was like the bustling New York City nights in the early ’60s, in the Village. None of us were famous; we were just doing what our hearts guided us to do and, of course, survive.

We would play in the little coffee shops and pass a basket around for money. Tim Hardin and I performed a duet for quite a while. Lenny and I were friends, and I went to jail with him when they arrested him for obscenity after a show at the Cafe Au Go Go. When they said they were going to take him away, he said, “What are the charges?” and the arresting officer said, “Oh, I don’t know, Lenny, it’s A one 0, or A 27 something.” I said, “Wait a minute—you’re gonna take this guy away and you don’t know what you’re charging him with?” The cop then said to Lenny, “Is this a friend of yours?” He said yes, and the cop said, “Fine, you can come with him.”

How did you originally meet Joni Mitchell (at the time Anderson)…you taught her some guitar technique…

In those days, when you were booked into a club, you would be booked in for a week up to two weeks. Joni was the waitress there. She asked me if I would show her some guitar techniques on my 12-string. I showed her what I was capable of at the time and also showed her open tunings. What I remember is that when she sat with the instrument for the first time, she was immediately comfortable. I knew she would be a player. She did not sing for me when we were having those lessons. We did become friends, but no relationship evolved other than that. I know that she acknowledged I had shown her these things, but I don’t know if she remembers now. I’d like to think she does, and I’d love to hang out with her just once more before we transform.

What inspired your decision to travel to India? During your travels, you met record producer Denis Preston in London, who signed you to Columbia Records. How did that come about and what did you think of London in the 60s?

As I mentioned before, when you were booked into a club it would be at least a week. I was booked into a club called the Purple Onion in Toronto. I had a night off and a friend of mine said, “You gotta go see this guy. He plays an instrument called the Sitar.” I went and saw the concert and it blew me away. I went backstage and met Ravi Shankar. He was so gracious. I asked him all about the instrument and how he played it, and he let me play his sitar, set me down, showed me the wire pic, and got me started. I met Ravi several more times over the years, and I remember a specific session in Paris where he invited me to a recording session and asked me to turn the pages of the score for him of Vivaldi’s ‘Four Seasons’ recorded for sitar and Cristal Baschet Glass Harp developed by the Baschet brothers, Francois and Bernard. I don’t know what happened in those sessions, but it was extraordinary.

And I don’t know how it got started, but I never actually got to India, because, as you said, I met Denis Preston at a party where I was playing and he asked me if I’d like to make a record. I said sure, but I don’t want any time clauses in the contract, because I had planned to go to India and that’s when my career as a professional musician started. One thing I remember was meeting all the guys in The Who. They were in the studio recording ‘My Generation.’ Keith Moon and I got on really well. He thought my Texas accent was hilarious.

Being in London was difficult because I had no money and initially didn’t know anyone, but I began to meet people and other musicians including Brian Jones, who became a close friend, Donovan, The Beatles, and pretty much everybody you’ve ever heard of. But you need to understand that there was no concept of some kind of history being made by meeting these people. We were all just a bunch of musicians getting stoned and playing music.

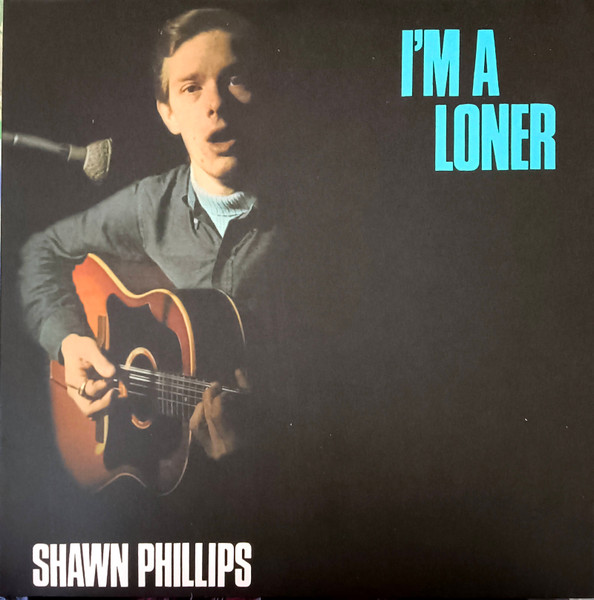

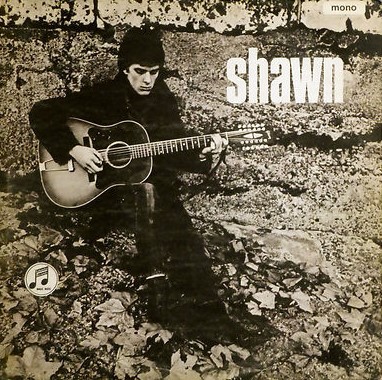

Looking back at your debut albums, ‘I’m a Loner’ and ‘Shawn,’ what challenges did you face in getting your music heard? Tell us, how do you enjoy those early recordings today?

I didn’t think about getting the music heard; I left that up to the business end of the music business. Truthfully, I don’t listen to what I’ve done; I just try to move on as a musician.

“I came up with the guitar riff for ‘Season Of The Witch'”

What was it like collaborating with Donovan on the cult classic ‘Season of the Witch’? You collaborated on several albums with Donovan, right?

Look, this is the way it would happen. Donovan and I would sit across the room from each other and I would play the guitar. This took place in an apartment in New York City that we had rented for the tour that he was doing. I came up with the guitar riff for ‘Season Of The Witch’ and Don started singing. That happened on several other songs as well, but they never became a hit. Donovan has now acknowledged that I wrote the music, but he got all the royalties.

You contributed backing vocals on ‘Lovely Rita’ for The Beatles. Can you describe how that collaboration came to be and what it was like to work with The Beatles?

Sure, we had been invited to come to the studio because Paul was going to put the pianos on the end of the song ‘A Day In The Life.’ I went with my friend Steve Saunders and Dave Crosby was there—we had been friends in New York long before that. At some point, Paul said we needed backup vocals on lovely ‘Rita Meter Maid,’ so he told us what to sing and we went in the booth and did it.

At the same session, George had a lead guitar riff he wanted me to hear. He gave me a guitar, played the riff on his, and said, “Play this back.” We did that several times and it got faster and faster, but in the end I played it faster than he could, and he told me to fuck off with laughter.

You actually showed some basic sitar technique to George Harrison?

Very shortly after doing the vocals for the song, George asked if I would show him some sitar techniques. I think I went to his house for dinner about five times and showed him the basics—how to sit with it, how to tune it, how to tune the sympathetic strings to the melody you’re going to play, stuff like that. He carried on from there and met Ravi sometime later.

Looking back, what were some of the biggest challenges you faced while incorporating non-Western instruments into your music?

There weren’t that many challenges; if anything, it was the tuning of the sitar and the position of the frets on the instrument so that it coincided with the western music scale.

You spent considerable time in Europe. What places did you travel to, and how did the culture and experiences influence your life back then?

Most of the time initially was in England, then a stint in France, then back to England, and finally, when my work permit had expired, I went to Italy on July 7, 1967. I remained there till 1980, then the 9.6-magnitude earthquake happened and I moved back to Los Angeles. Out of the frying pan into the fire. Haha!!! I can tell you I began dreaming in Italian, so that tells you how well you understand a language other than yours.

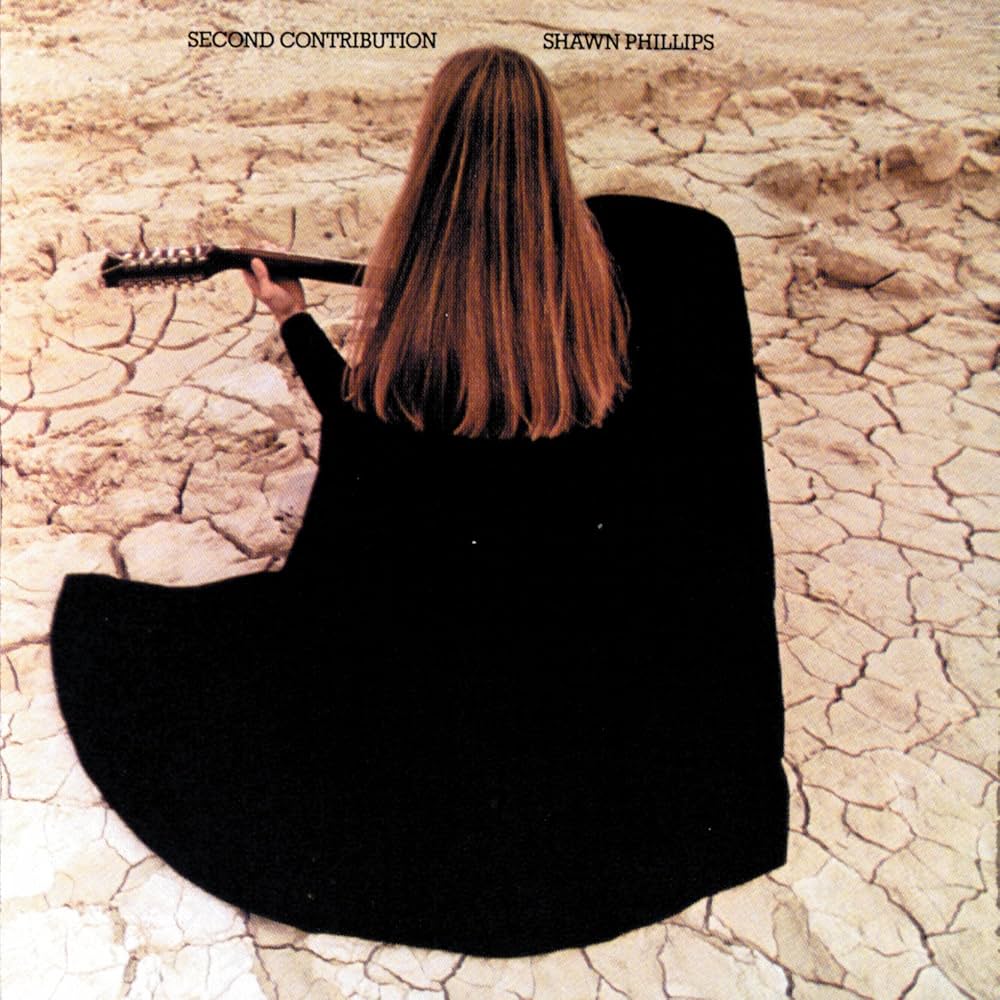

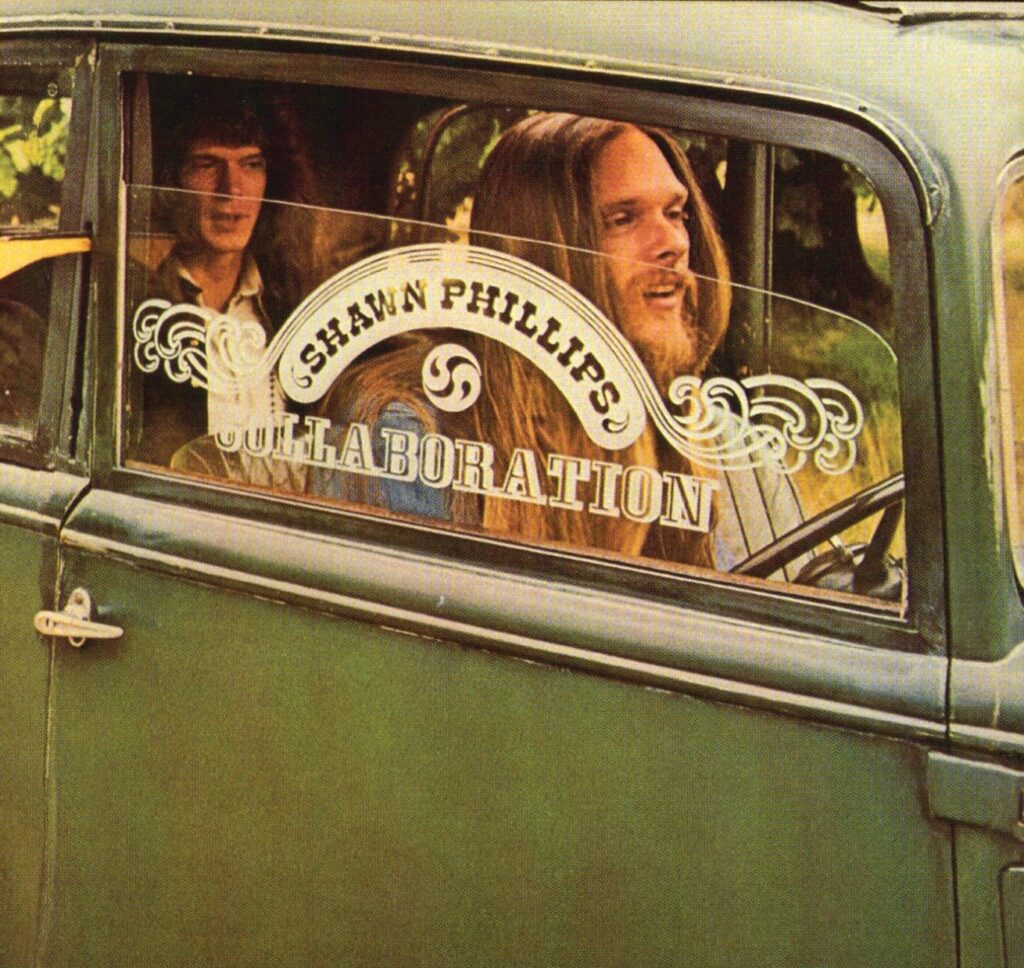

Your Trilogy—’The Contribution,’ ‘Second Contribution,’ and ‘Collaboration’—marks significant milestones in your career. What vision did you have for these works, and how do they contribute to your overall musical narrative?

It was all about playing music with other musicians. I had met Paul Buckmaster and Peter Robinson, and we just hit it off. Paul was an absolute genius, working with Elton John and many others, and Peter understood my passion for classical music. They had seen me in a movie called ‘Run With The Wind’ with an actress named Francesca Annis. Paul introduced me to Peter.

They had those names—’Contribution,’ etc.—because to me that’s what they were for: people. That was it, a sharing of my work.

“I write… anger, wonder, and technique”

Can you describe your songwriting process during the creation of your early albums? How has it evolved over time? Is it a deliberate craft or more of a spontaneous, magical occurrence? How do you nurture inspiration?

I have three criteria with which I write… anger, wonder, and technique. Anger is when you look at the world around you, and if you’re satisfied with what you see, then you’re probably certifiable. Wonder… to be attentive to every drop of rain on every blade of grass; and technique is keeping a balance between the first two. I have a discipline when I write my songs: I do not leave the room after writing the first line until I write the last line. I think the longest time I ever took to write a song was when I wrote ‘Talking In The Garden.’ It took almost 2 weeks. My friend Anello Capuano brought me my meals. I never edit. I believe your first insight is always the right one. If you start writing a song and you leave the room to go get something to eat, or whatever, you will lose your initial train of thought. I cannot explain how it happens; it just channels through. To this day, I never eat during the day because I never know when I’m going to write. I only eat dinner in the evenings. Everything I write is guided by a spiritual experience that I once had when I was in my early 20s. This was not a vision; it was an organic, instantaneous physical state of being that changed my life and my entire existence.

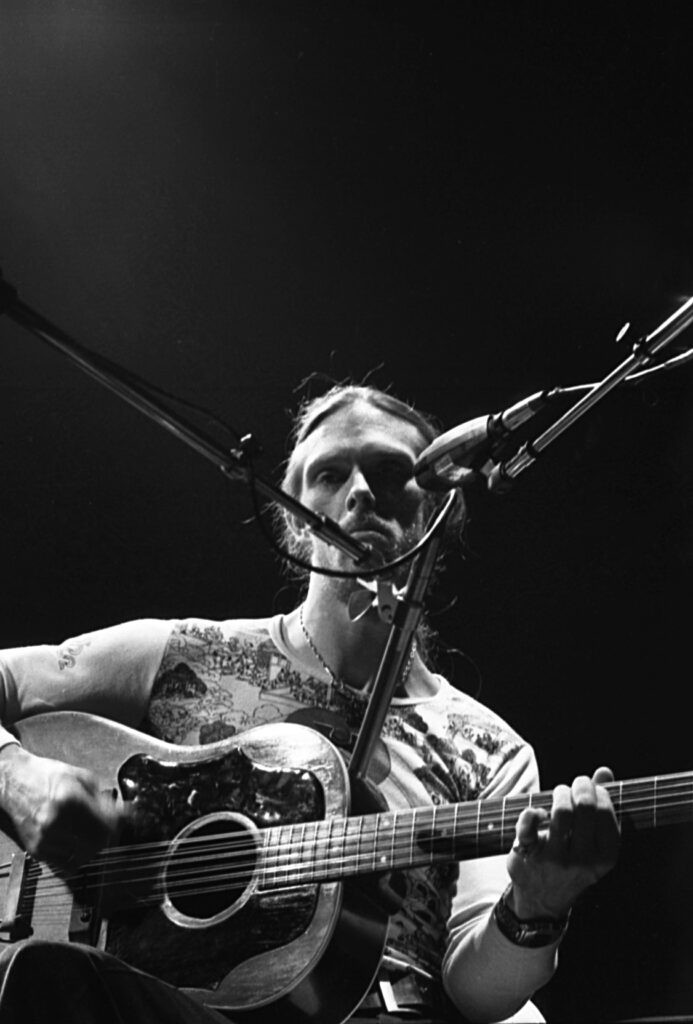

Securing a double standing ovation in front of 657,000 people at the Isle of Wight Festival is an incredible feat. How did that moment feel amidst the whirlwind of fame, and did it change your relationship with performing?

It was an incredible moment for me. It was a highlight of my life for many years, but it faded away when I had my first lead as an EMT with a female patient who had fractured her pelvis in a fall. I took great pains to keep her painless as we were preparing to transport her to the hospital. When we got there, she was very frightened, as she had never been to the hospital before. I told her she was in good hands and that they would take care of her. She grabbed me by the hand, looked me in the eyes, and said, “Thank you so much for taking care of me.” And the Isle of Wight disappeared in the distance.

My performances are all about the moment you are in front of the audience, yes. Today, my performances are not just about standing there with a guitar and singing a tune, as I have evolved my stage performances with technology to make as much sound as possible—that being the music I was hearing in my head during solo performances with just a guitar. It became boring. Everything I do is in real time. Using two Roland guitar synthesizers, I am able to emulate an entire Symphony Orchestra, or a full-on rock band. It’s great fun but requires a great deal of attention to all the changes that take place in a performance like that. Some serious wood shedding has to go down to do my shows. I record guitars and bass in real time in front of the audience with a Line 6 JM4 looper, up to nine layers of sound, and up to 10 minutes per song.

You were offered a role in Jesus Christ Superstar but withdrew due to contractual disagreements. Did this decision reflect a deeper realization about your artistic integrity and the allure of Broadway?

Not really, although it was a joy to duet with Carl Anderson. Carl was the only singer who ever made me weep. He was a very dear friend. It fell apart because the producer could not make any money out of me; I had a manager, booking agency, publisher, and record company. I just carried on as usual after it fell apart.

How do you view the relationship between spirituality and your art?

They are one and the same. When they happen, they fuel themselves.

Despite your immense talent, you’ve often avoided the mainstream spotlight. Was this a conscious decision, or did it emerge organically from your vision as an artist?

I never actually avoided the spotlight. Let’s be clear: at one point I had to make a decision. Was I gonna be a businessman or an artist? I don’t care what anybody says; you cannot be both. Either one or the other will suffer weakness and insufficiency. I chose to be an artist and to concentrate solely on creativity. In today’s world, this has cost me dearly. It was my choice not to “Take direction” from anyone in the music industry.

You’ve collaborated with artists from various cultures. Can you share a particular instance where a collaboration challenged your understanding of music or pushed you out of your comfort zone?

Hey man, just being in the same room with Leland Sklar or Jeff Porcaro—many musicians of that level push me out of the room! I can’t read or write a note of music, but one thing did happen in Italy when I met a man named James Smith, who was the first violinist for the orchestra that plays for the Queen. I lamented the fact that I couldn’t read or write music after I had played him a few things I had composed. He said, “Listen, it took me 20 years to forget everything I have ever learned from the Royal Academy of Music in London so that I could write an original melody. It would hurt you more than help you to learn at this point.” So sometimes I’m a bit aghast with some of the players I work with.

Bill Graham once referred to you as “the best-kept secret in the music business.” How do you feel about that title?

Well, it’s certainly the truth financially. If they don’t play you on the radio, you’re a secret—and they stopped playing me a long time ago… well, some stations will play some stuff, but radio play for artists is controlled almost entirely by the music industry.

You mentioned that your work as an EMT gave you a profound sense of purpose. How do you balance your passion for music with your commitment to helping others?

I’ll refer you to the statement in the Isle of Wight question.

After a significant hiatus from music between 1994 and 2003, how did your experiences as a firefighter and EMT shape your perspective on life and art? Did those years influence any of your later work?

It kind of all boils down to how to help the people around me and us. You are helping people in a moment when they cannot help themselves. The fact that you have to leave your ego behind you when you’re dealing with the disasters that affect people or a patient was very appealing to me. When you’re offstage, you’re the audience; when you’re onstage, you’re sacrosanct—for only that moment. That’s the only explanation I have.

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

Hard question. I’m not sure anyone influenced my own style, but people like Chick Corea, John McLaughlin, Al Di Meola, Alphonso Johnson, and Stanley Clarke certainly had—and have—my attention at all times. They are all friends of one level or another.

Finally, what currently occupies your life outside of music? Are there new projects or passions you’re exploring?

Right now I’m in the process of upgrading my studio because I’d like to make another album. I don’t have a title right now, but “Finale” might be appropriate.

I’ll share the lyric from one of the songs with you, which will give you some idea of where it might go. Before I go, I would like to wish all your readers

Health, Love and Clarity!

All the love is nonexistent in the world

if the people cannot feel it in their hearts,

we are such a stupid species simply rolling in our feces

and the world remains perpetually in the dark

In the world of our endeavors we cannot remain forever

if we make the choices amplified by greed

if we glorify the bars instead of reaching for the stars

we will never reach the goal of human needs

We have chosen competition the fairytales about religions

when inside we all have equal powers of the Gods

and there are those among us with the power of decisions

to eradicate all those who can’t or won’t applaud

Now our planet is a whisper with the spark of our existence

in the magnitude of galaxies beyond

but we can make the right decisions to incorporate our visions

and eliminate the borders we have drawn

When the forces of humanity, overcome our pale insanity

we will solidify our journey towards the light

we will defeat the fear of living, remove the mirror of our vanity

and reach the goal of whatever’s in our sight

When consciousness is enabled, we will share the very table

that we should have created long ago

it it is the essence of our existence, our empathetic lack of distance

that will sustain us on and on.

A hint….this song may end up sounding like a Bulgarian Choir as voices enter!

Klemen Breznikar

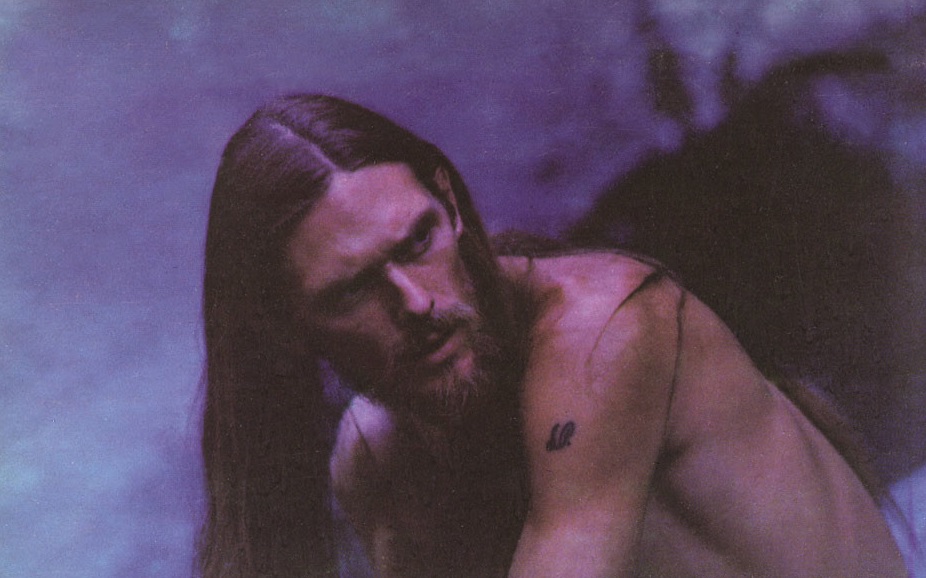

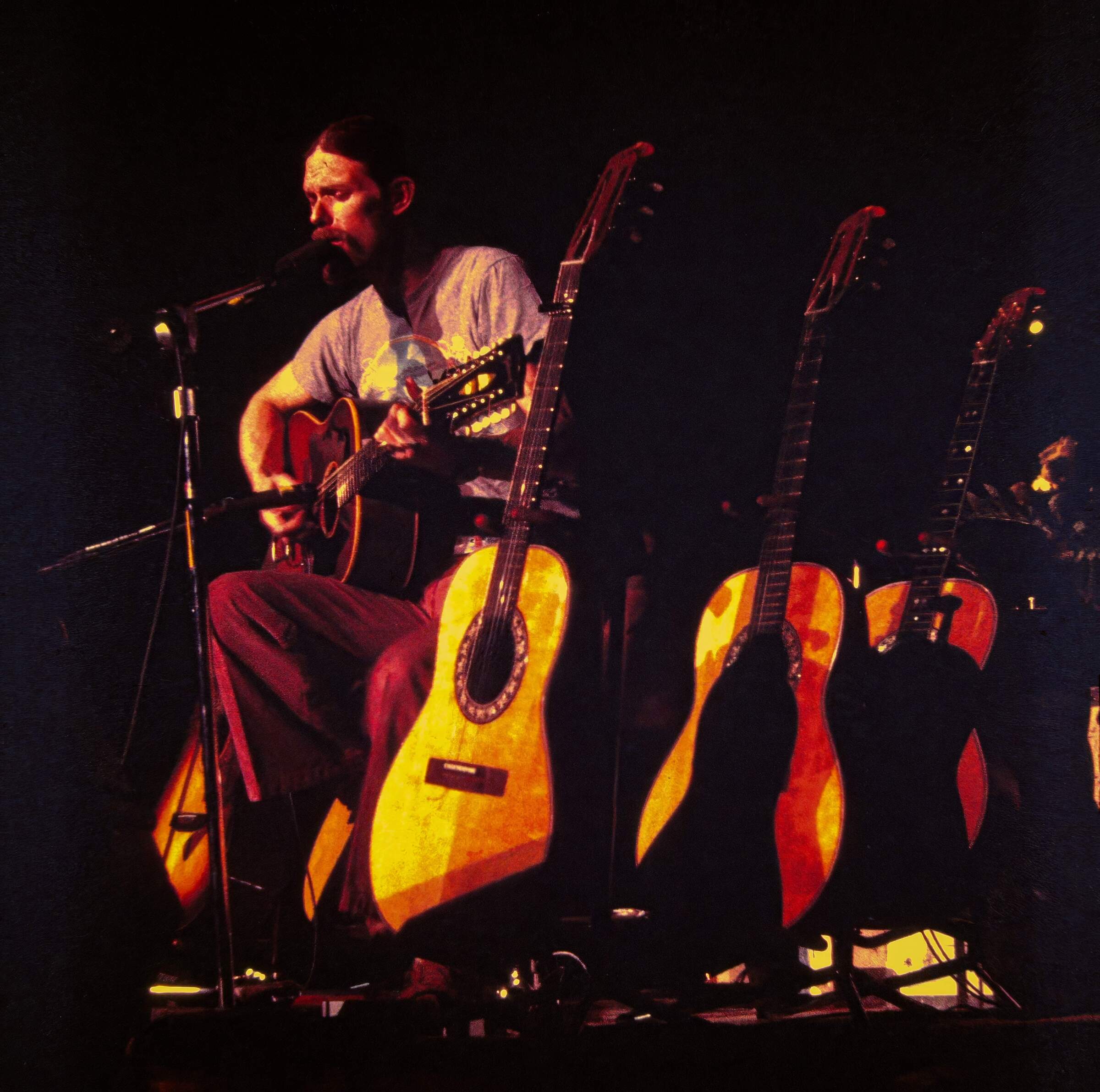

Headline photo: Shawn Phillips | February 7 1976 at Hill Auditorium, Ann Arbor, MI | Credit: Michael Corpe

Shawn Phillips Official Website / Facebook / Bandcamp / YouTube

Think Like A Key Music Official Website / Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Bandcamp / YouTube

thanks indeed , succinct and informative

Great interview. Enlightening answers to the good questions.

Shawn has made music that touches the heart of people who critically think about the world. His music and himself are reflections of the times we live and the soul of our hearts.

Excellent! Thank you!

You music has touched me and opened my mind in so many ways. I appreciate everything that you gifted to me Shawn. I look forward to sitting right in front of you once more at Sam’s Burger Joint as we did some years back.