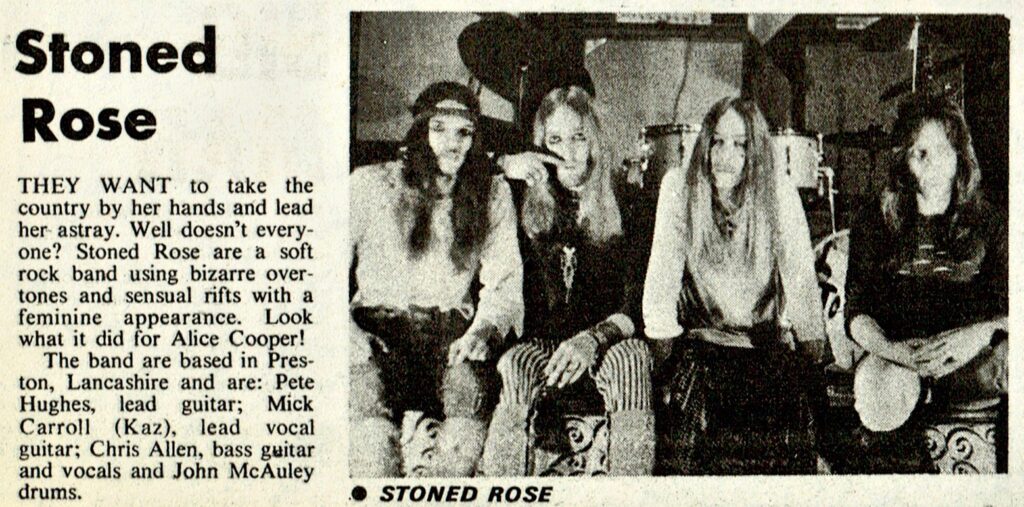

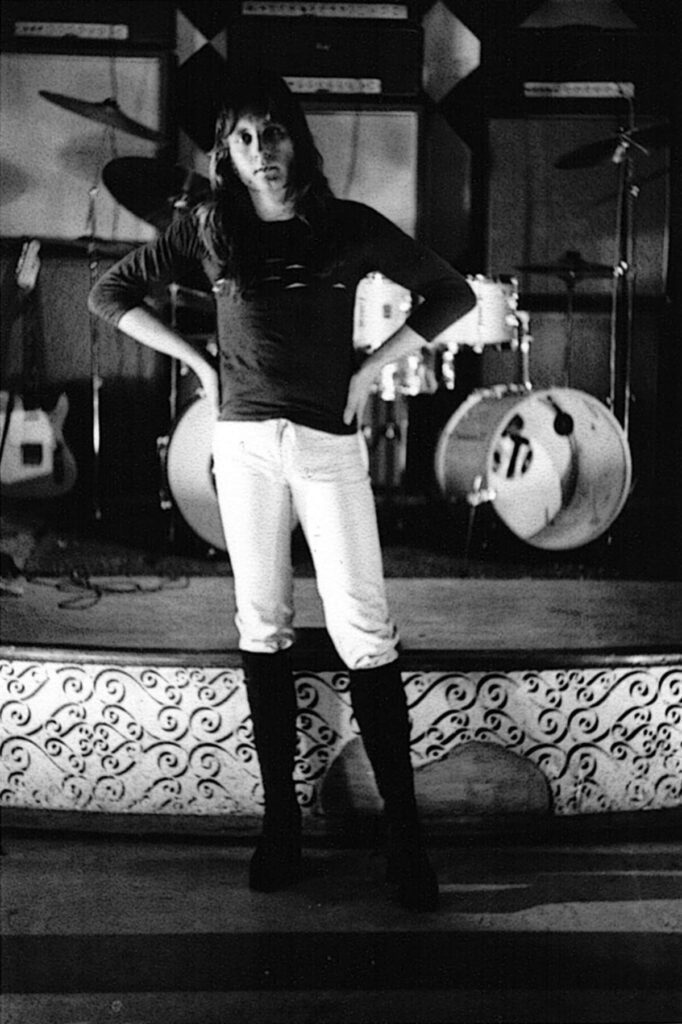

Stoned Rose | Interview | Resurrection of Lost Acetates

After decades spent languishing in obscurity, the thunderous sound of Stoned Rose is finally breaking free from the depths of underground history, with their long-lost recordings resurrected by Guerssen.

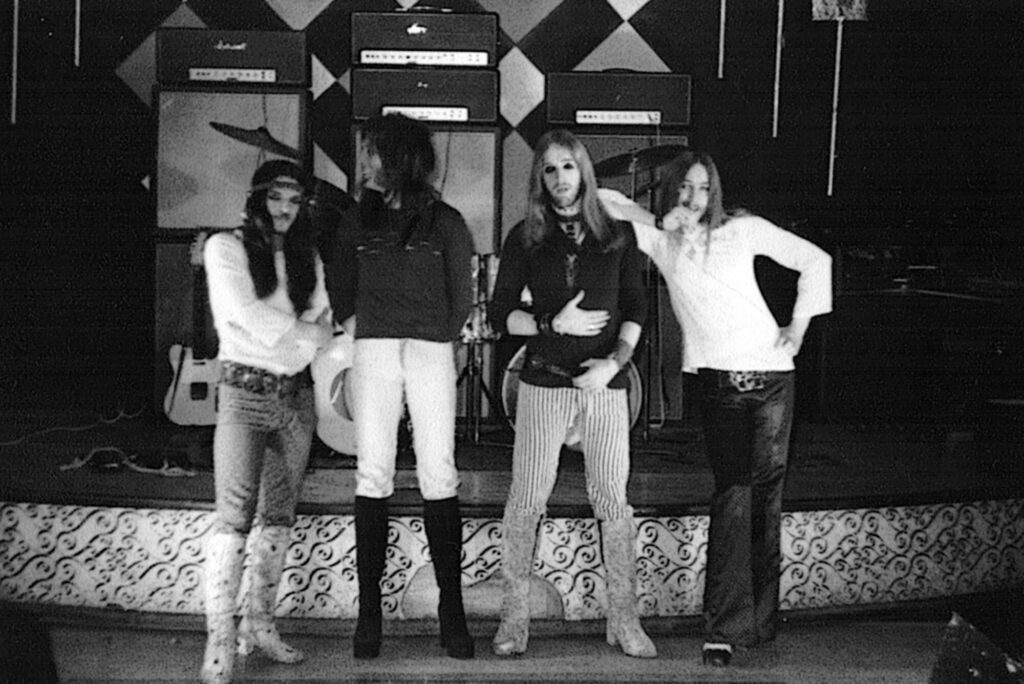

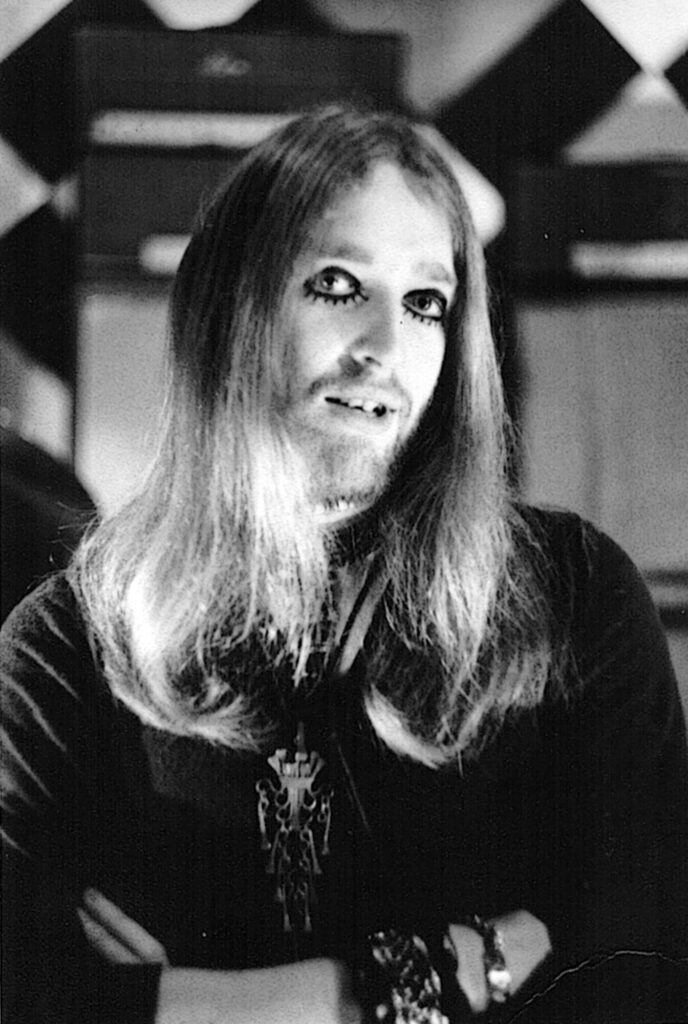

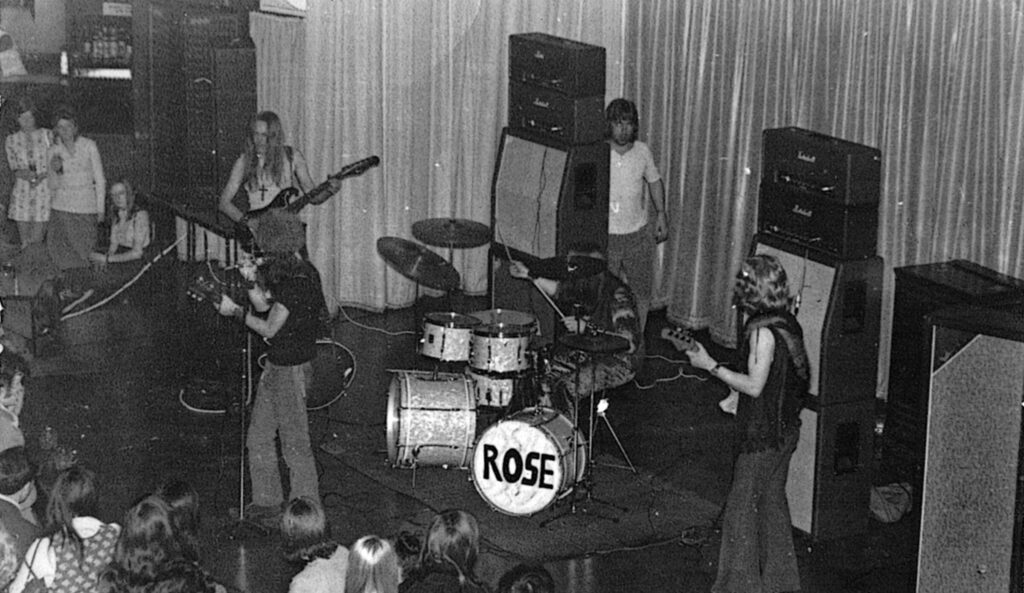

This collection isn’t merely a bunch of tracks; it’s a time machine that catapults you back to an era when incense wafted through the air, mingling with the sweet scent of rebellion and the flickering promise of peace and love. Heavy-progressive, proto-metal, and psychedelic hard rock collide in the lost sounds of Stoned Rose, originally birthed as One Step Beyond. This Preston, UK band morphed into a force that shared stages with legends like Stray and May Blitz, leaving an indelible mark on the underground music scene. With roots tracing back to iconic venues like the Cavern and the Temple, their recordings—pulled from rare acetates and demo tapes—are treasures for any fan of underground psych and heavy rock.

“Back in the early ’70s, there was a big network of underground venues throughout the UK”

Pete —take me back to those first sparks. What was it about music that grabbed you by the soul? Was there a particular moment, maybe a record or a live performance, that made you think, “This is it—this is what I have to do with my life?”

Peter Hughes: Yes, when I was 11 years old and I heard The Shadows and their fantastic tunes like ‘Wonderful Land,’ ‘Apache,’ ‘FBI,’ etc. It just blew me away, and to this day, I still get a tingle when I hear those tunes. Nobody could ever do them as well as The Shadows. At that point, as an eleven-year-old, I wanted to learn to play the guitar. I didn’t realize that that was the most important decision I ever made and that it would completely change my life, leading to so many wonderful experiences all over the world that I would never have been able to have if I hadn’t learned to play the guitar.

Preston, 1960s—it doesn’t exactly scream “birthplace of heavy-prog and proto-metal.” How did the environment you grew up in—socially, musically, culturally—influence the way Stoned Rose’s sound evolved?

I guess that Mick Carroll and I were originally influenced as 14- or 15-year-olds by all the great bands that were coming out around 1964-65. We started to write songs together; a big influence on me as a lyric writer was Bob Dylan, and of course, others as well.

You evolved from One Step Beyond to Stoned Rose—how did that metamorphosis happen? What was the driving force behind shedding one skin for another, musically and personally?

One Step Beyond as a band did pretty much 50-50 percent between covers and original material. We wanted to do all original material, so we reunited with original One Step Beyond drummer John McAuley and a friend of mine, Steve Woodworth, and Stoned Rose was created. The band just evolved based on the songs that Mick and I were writing.

Did One Step Beyond record anything? Where did you play?

One Step Beyond recorded three songs at a studio called Deroy in 1968: a cover of ‘You Keep Me Hanging On,’ and two original songs, ‘Dreaming’ and ‘The Scene of the Lemon Queen’ (which was recently included on a compilation album called ‘I Think I’m Going Weird’). Throughout 1968, we played mainly in Liverpool at iconic venues like the original Cavern, The Blue Angel, Litherland Town Hall, etc.

Can you elaborate on how the formation of Stoned Rose happened?

As I said, we wanted a change of personnel. We started rehearsing in Liverpool and Preston with the new songs that Mick and I were writing, and the arrangements of the songs were created jointly as a band. The Stoned Rose sound was created organically as a band.

The late ’60s and early ’70s were a whirlwind of sounds and scenes. What was it like to be a part of that? Did you feel like you were riding the wave of something bigger, or were you more focused on carving out your own niche in the chaos?

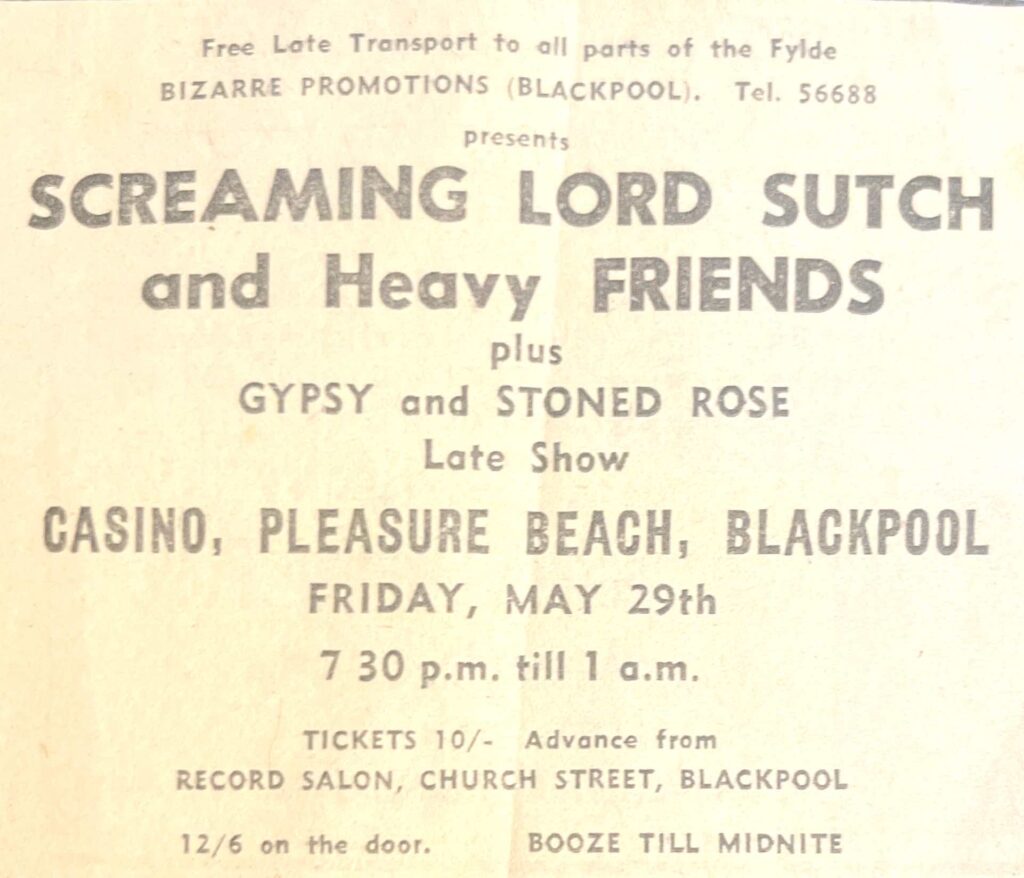

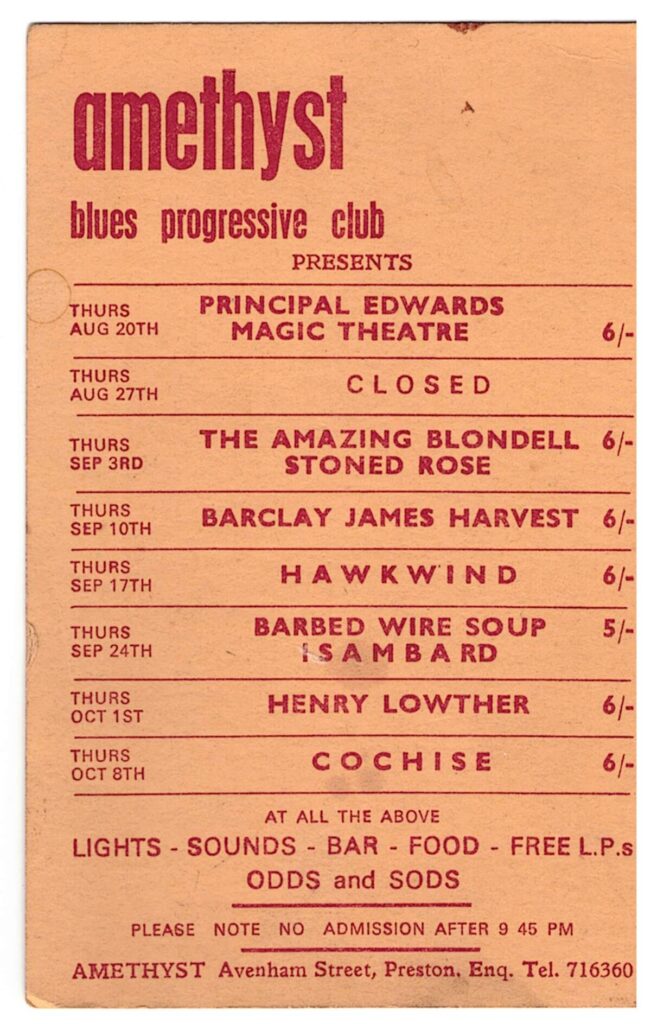

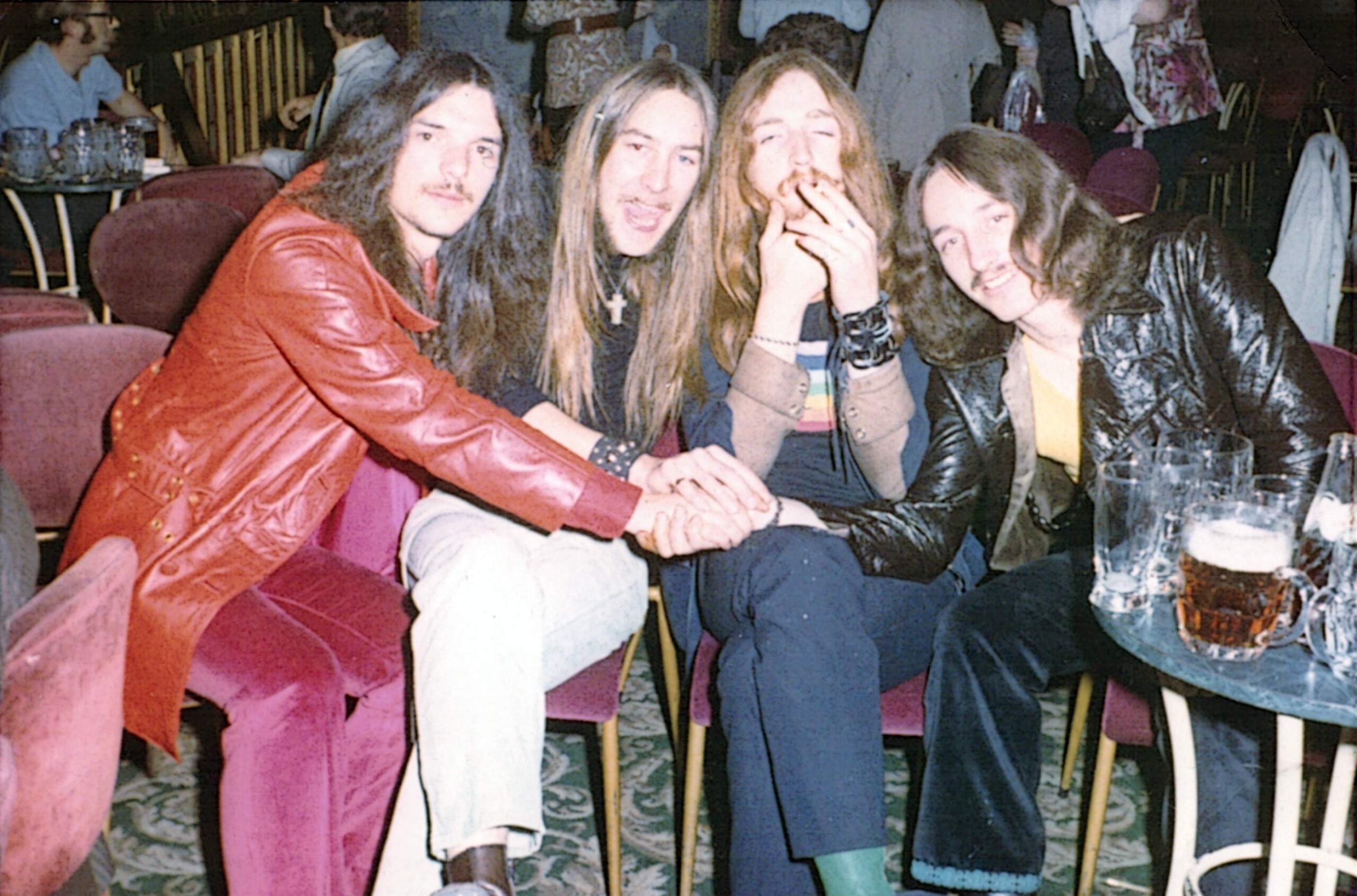

It truly was an amazing time, and it was great to be part of that. We played with lots of great bands. Back in the early ’70s, there was a big network of underground venues throughout the UK, and we were privileged to be part of that. It was great and a lot of fun.

Tell us about the name of the band.

I came up with the name Stoned Rose. Looking back, I don’t know where it came from, but I think that the name Stoned Rose was possibly mentioned—not as a band, but as part of a surreal dialogue on the back of a Bob Dylan album, possibly ‘Highway 61 Revisited.’ It was something that just somehow stuck in the back of my mind.

Your paths crossed with Chris Allen, who later went on to Ultravox. How did his involvement shape the band’s sound during his tenure? Did you feel a shift in direction when he left?

Our original bass player, Steve Woodworth, left the band to go to university. We put an advert in Melody Maker for a new bass player. We had many responses from all over the UK. Chris was from London. We met up with him, and immediately we all got on like a house on fire. Chris was a great bass player and a great guy. After Stoned Rose, I was really pleased for him that he had all the success with Ultravox. He deserved it. He was a diamond.

Working with agencies like Nemesis and Tramps, how did that influence your trajectory as a band? Did the association with Toni Iommi’s agency bring any unexpected opportunities—or challenges?

They were good agencies to work with. Tony Iommi’s agency, Tramps, was mainly focused on Birmingham bands like Judas Priest and Medicine Head, etc. We kind of felt a bit like outsiders.

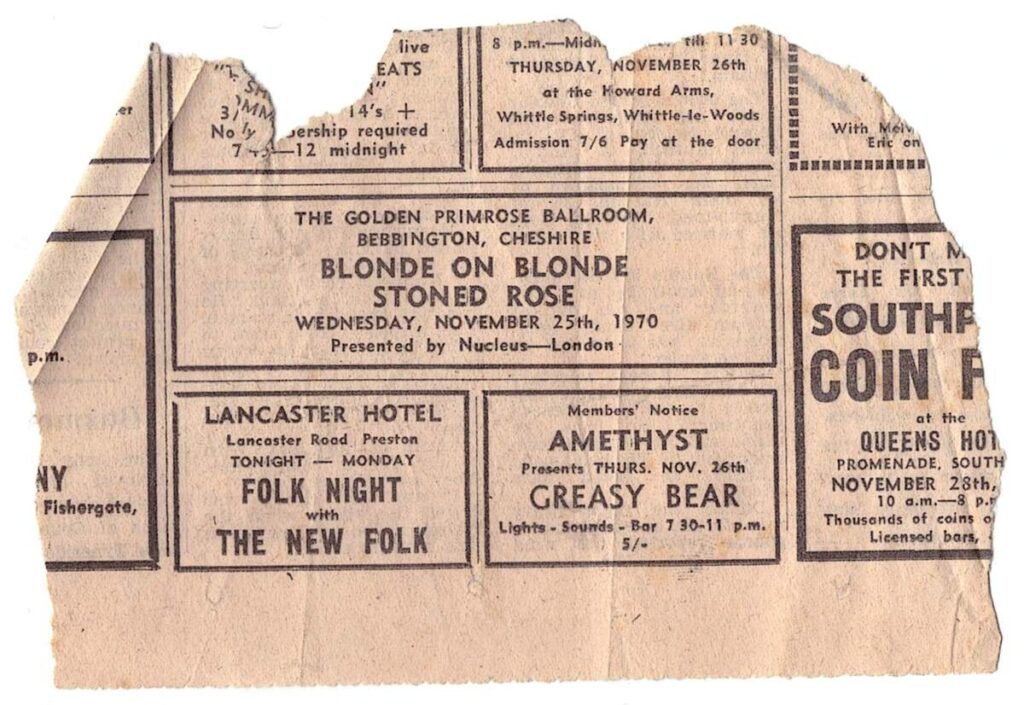

The Temple, the Cavern, underground clubs, universities—what was the energy like at those early Stoned Rose gigs? Can you paint a picture of the scene for those of us who weren’t there? What was it like sharing the stage with bands like Stray, May Blitz, and Blonde On Blonde?

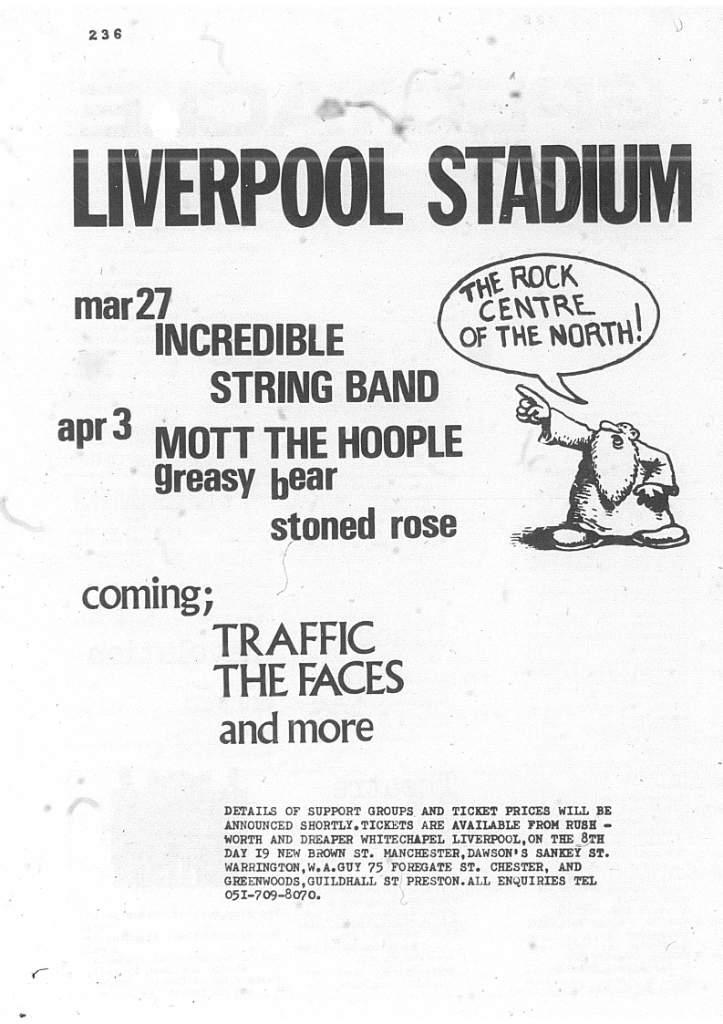

Again, it was great times. We knew most of the bands on the circuit. The standout bands that we were lucky enough to work with included, from America, Canned Heat (who were great guys) and The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. Also, Mott The Hoople at Liverpool Stadium. They were brilliant. This was before Bowie gave them ‘All The Young Dudes.’

Any particular gig that stands out, where everything just clicked—or perhaps one where it all went spectacularly off the rails? What were those early crowds like? Did they “get” what you were doing right away, or was it more of a slow burn?

There really were so many great gigs. The Liverpool Stadium gig with Mott sticks in my mind. But really, Stoned Rose went down great pretty much everywhere we played.

You’ve got these recordings that are being unearthed after decades—acetates, demo tapes. What’s it like revisiting this material now, with so much time and distance between then and now? Do they sound different to you today?

To be honest, it is truly amazing that these tracks from so long ago are now being released. It’s a strange feeling, but one that really brings back to life how we were when we were so young. As I have said, they were great days—truly amazing—and I am so glad and proud to have been part of that.

Where were those recordings stored?

In my bedroom!!

Would love it if you could tell us about where you recorded them, about the songs, etc. Please share your recollections of the sessions.

The tracks were recorded at a studio in Luton in January 1970, and a bit later at a studio called Deroy in Carnforth. The sessions were pretty rushed, to be honest.

Would you share your insight on the albums’ tracks?

Track 1, ‘Day to Day,’ was recorded live onto a reel-to-reel domestic tape recorder. We just played the song live once, and that was it!! This track featured Chris Allen, as did the last two songs, ’17th Century Doll’ and ’11th Hour Sour.’

Let’s talk about the track ‘Heaven Is Pink Primroses in Everyone’s Sunset’—there’s something deeply evocative in that title alone. What was the story behind that track? And what about the others? Do they hold together as a concept, or were they more spontaneous creations?

In July 1967, me and Mick and a couple of friends went down to Bournemouth for a week’s holiday. It was the height of the Hippie period. We clubbed up and bought a second-hand acoustic guitar, and we used to sit in the gardens every day playing the guitar and singing. ‘Heaven Is Pink Primroses’ was just a reflection of those days—HIPPIES.

Why do you think it’s taken so long for this music to see the light of day? Was it simply lost to time, or was there a sense of it needing to wait for the right moment, the right audience?

Unfortunately, we had no proper management and no one to get the recordings heard by the right people. We were just young and unlucky that no one heard the recordings. So yes, it was lost in time.

Stoned Rose came to an end like so many bands of the era—quietly, almost unnoticed by the wider world. What led to the disbanding? Was it the usual story of artistic differences, or was there something more personal at play?

No, there was nothing personal about it. We just decided to move on to other things.

After the band split, what was next for each of you? Did you move on to other projects, or did you step away from the music scene for a while? Was there ever a moment of “What if we’d stuck together a little longer?”

Me and Mick decided to concentrate on songwriting. This led us to signing a publishing contract with CBS – April Music. We then signed a contract with Warner Brothers and had a big hit in Australia with a song called ‘Too Much Fandango’ under the name of RITZI.

Chris went back to London and formed a new band called Tiger Lily, who would later become Ultravox!

John continued playing with various bands.

Looking back now, what’s your perspective on the legacy of Stoned Rose?

Well, I think that Stoned Rose was unlucky. I don’t think it was a lost chapter; they were great days, and it is great that it is now seeing the light of day.

If you could go back and change one thing about your time with Stoned Rose, what would it be? A decision, a song, a gig—anything that you feel might have altered the course of the band’s history?

If I had known back then what I know now, I would have hawked all the recordings around all the labels in London, and I think that we may well have been signed.

What would be the craziest gig you ever did?

Too many to say. They were pretty much all crazy!!

Tell us about the instruments and gear you had…

We used all Marshall gear. I played a blonde Fender Telecaster, and Chris had a Gibson SG bass guitar. John had a double bass drum kit, very much like Ginger Baker, his hero.

Did you get any local airplay?

Yes, on local radio.

Is there anything unreleased? Maybe a related project?

For myself and Mick, we formed a band called Ritzi after Stoned Rose. As previously mentioned, we had a major hit in Australia with ‘Too Much Fandango,’ which has been re-released on several “Greatest Hits of the 70’s” albums. We have a lot of high-quality unreleased recordings by Ritzi. Maybe they will come out one day.

Now that this material is finally being released, do you feel like there’s a sense of closure, or does it open up old desires to maybe pick up where you left off?

I have never stopped playing with very good bands all over the world. It’s rock ‘n’ roll; I’m afraid that it gets into your blood. It’s a blessing and a curse!!

What’s the one thing you want listeners to take away from this album? What should they feel, see, or understand about Stoned Rose that might have been overlooked or forgotten all these years?

It’s real, it’s original, and we put a great deal of time and effort into Stoned Rose. It’s a band that I am very proud of, and I’m so glad to have been part of it.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Strange vibrations make me feel it’s OK, living like an actor from day to day.

Klemen Breznikar

Guerssen Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube

John McAuley is my brother and to find this article is like gold! Thank you so much for publishing it.