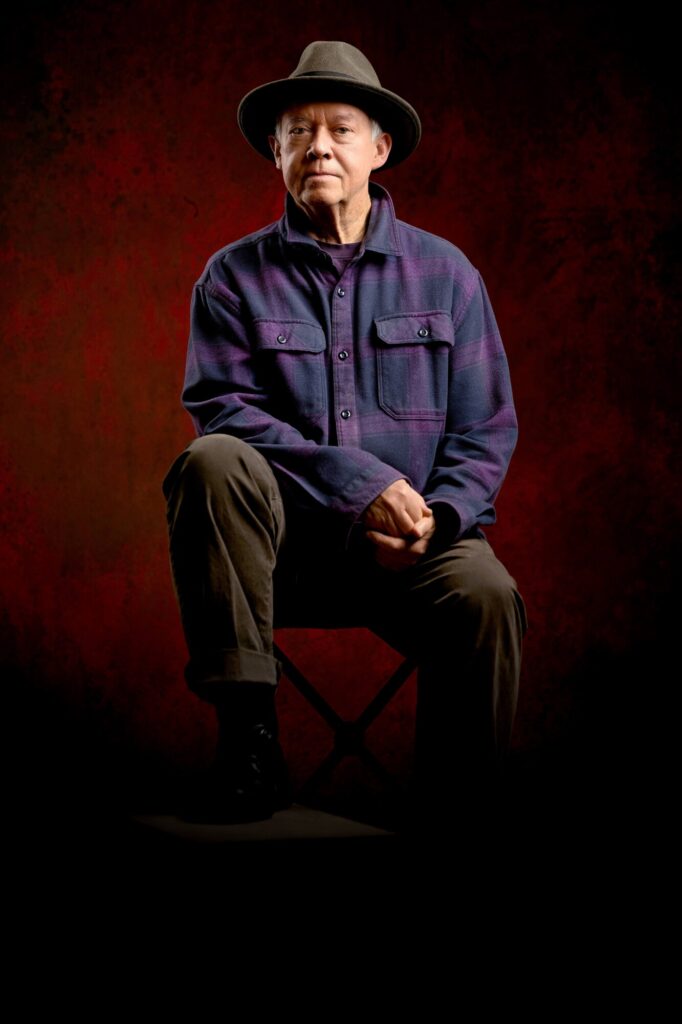

Greg Copeland | Interview | New EP, ‘Empire State’

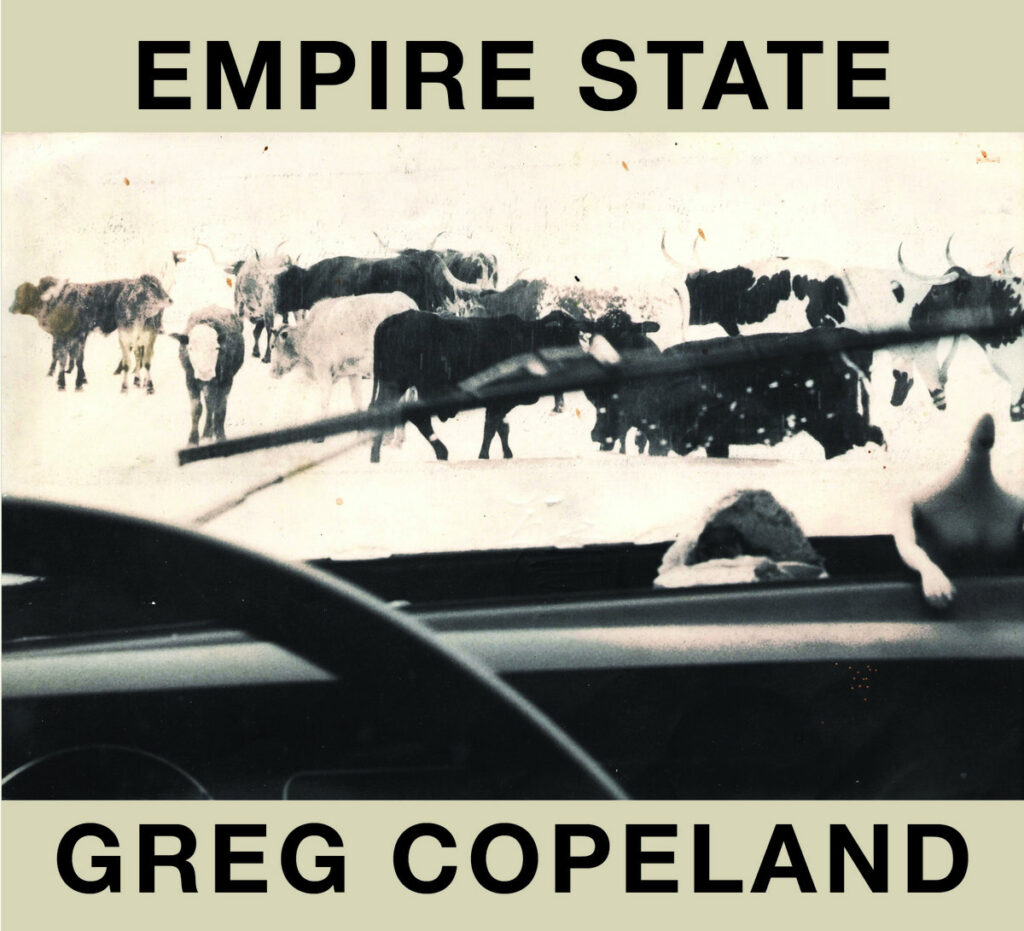

Greg Copeland, renowned for his pivotal collaborations with Jackson Browne and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, recently released his new EP, ‘Empire State,’ on September 6, 2024.

This highly anticipated EP is available through Franklin & Highland Recordings in the U.S. and Hemifrån/Paraply Records for international fans. Following his acclaimed 1982 debut ‘Revenge Will Come’ and the celebrated ‘The Tango Bar’ in 2020, Copeland’s ‘Empire State’ promises to build on his legacy of evocative songwriting and compelling storytelling. This EP marks a significant return for Copeland, who has spent the past 26 years away from recording. The new release reflects his matured perspective and artistic clarity, evolving from his previous works with a fresh and introspective approach.

Described by the New York Times as possessing a “feisty, original voice,” Copeland’s latest work continues to blend Southern California’s atmospheric influences with his distinctive, raw lyrical style. ‘Empire State’ explores themes of resilience and reflection, echoing the narrative depth and grit of his earlier music while introducing a new sonic dimension.

This EP follows in the footsteps of Copeland’s ‘Diana and James’ and ‘The Tango Bar,’ each album showcasing his ability to intertwine personal and political themes with a rich, narrative-driven sound. Featuring collaborations with notable musicians, ‘Empire State’ reaffirms Copeland’s place in the Americana and folk traditions, offering fans a fresh yet familiar experience rooted in his storied career.

As Copeland celebrates the release of ‘Empire State,’ listeners can look forward to a powerful collection of songs that continue his tradition of blending poetic lyricism with the distinctive ambiance of Southern California, cementing his status as a timeless and influential artist.

“The songs on ‘Tango Bar’ and ‘Empire State’ are meant to go together.”

Your early career saw collaborations with notable artists like Jackson Browne and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. How did those experiences shape your approach to songwriting?

Greg Copeland: Actually, it shaped my approach to life more than it shaped my approach to songwriting. Everybody in that circle of friends was just beginning to sort things out, like every other just-barely-post-high-school monkey person. I didn’t write songs during that period; I wrote poems that were turned into songs by other people, mainly Steve Noonan and Jackson. The music for those songs was all theirs, and I loved it, and I was just glad to be part of it. I still am.

The very first time I ever heard anybody play guitar live was Noonan sitting in the passenger seat of my car, in the parking lot of our school—literally a foot and a half away from me—and to this day, I can feel that sound going right through my body. It was like discovering a trap door to a hidden room. But I didn’t own a guitar until I was in my early 30s. That might have saved me from having to worry about sounding like anybody else.

I would love it if you could speak about growing up and what some of your first involvements in music were.

I grew up in Orange County in the early ‘60s (Google the John Birch Society), so I didn’t have much contact with anything but madras shirts and student body elections. And then? Hello, folk music—honest, rightly pissed off, articulate, and (at least for a while) it seemed to get better every time you heard something new. The lyrics were rich, the harmonies sounded like real people singing. The songs were about people’s actual lives. I remember the very moment and exactly where I was standing when I heard that Kennedy had been shot. Seven months later, I moved to San Francisco. I had absolutely no idea what I was in for.

How do you remember the 60s?

Lots of traveling. A friend and I hitchhiked from Long Beach to Veracruz, and I was completely hooked on going places I had never been, so we just kept traveling. It was glorious. I was never hassled, never got mugged, never felt like I was in danger. I wasn’t a hippie by any means, but for me, the core of hippie culture was a fundamental trust in the universe, and I got that from traveling, in spades, because it showed me that I could, in fact, trust the universe. And I did. And I still do.

‘Revenge Will Come’ was released to critical acclaim in 1982. What do you remember most vividly about the creation and reception of that album?

That was the first time I’d ever been in a recording studio, so it was like boot camp for happy people. Everybody in that band was wonderful. They were all probably wondering, “Why him?” but I was deep into learning mode, so I didn’t really notice. The label fired me before the album came out, so frankly, I wasn’t even aware of the reception until I was already trying to figure out what to do next. I was really scrambling, so I was incredibly grateful for all the surprising reviews and everything that came from that, but it was a little too late to save the day.

You co-wrote ‘The Fairest Of The Seasons’ with Jackson Browne, which was later recorded by Nico. Can you share the story behind that song and what it means to you today?

I was about to go traveling, and I had to leave my girlfriend. A hundred thousand songs have been written about that, but it was my first. I wrote it as a poem, and Jackson put that wonderful music to it, so it turned out great. A while ago, I saw a YouTube video of that song done by Laurena Segura, and it blew me away. For the very first time, it was like hearing somebody else’s song. I love the way she did it—just voice and guitar, and a beautiful bit of French horn that almost made me cry; it was so perfect. So, thanks to her if she’s out there. Nice job.

After a long hiatus, you returned with ‘Diana and James’ in 2008. What led to your break from music, and what inspired you to start writing and recording again?

After ‘Revenge Will Come,’ I was out of work and had a family, and I could either get a job or go down a real dark street, so I decided not to completely screw up everybody’s lives. It wasn’t really a tough choice. That lasted about 20 years. I don’t know why, but when 2000 came around, I just started getting songs again. It was like, “OK, well done, green light. Go.” And all kinds of new music started showing up, one after the other. I learned to play enough guitar to write, which was REALLY fun, and just kept writing. I tend to take a lot of time between records, largely because it takes a long time to live through this stuff. Albums are expensive to make, and it takes time to get the money together, so we usually record a couple at a time, see you back here again next year. This is a fabulous band, so it always works just fine, but it takes forever.

How did your perspective on music and life change during your time away from the industry, and how did that influence your later works, including ‘The Tango Bar’ and the latest EP, ‘Empire State’?

It did wonders for my work ethic. Having a job with real-life consequences for the lives of others meant having a focus and a commitment that I’d never needed before. So when the new songs started to arrive, my work ethic was already pretty strong, so I was able to deal with both sides of my life at the same time without going completely off the rails.

The whole point of my job as a lawyer was to find the truth, which is exactly what you do as a songwriter. So the two sides of my life turned out to be okay with one another. In terms of my life, ‘Diana and James’ is the Old Testament, and ‘Tango Bar’ and ‘Empire State’ together are the New Testament. I’m starting to feel like I’ve about said my peace.

‘We the Gathered’ has been described as both a hymn and a potential soundtrack for a Cormac McCarthy story. What inspired this unique blend?

They’re both about hard travel. The beauty at the bottom of the ditch.

Your latest EP, ‘Empire State,’ continues the themes explored in your previous works. Would you love it if you could reveal a bit more about it?

The songs on ‘Tango Bar’ and ‘Empire State’ are meant to go together. They’re about four people—the guy in ‘Let Him Dream,’ the girl in ‘Beaumont Taco Bell,’ the guy in ‘4:59:59,’ and the girl in ‘Empire State.’ Again, hard travel. Think Chaucer, but darker. As an American right now, I don’t have much interest in songs that just decorate the room. I prefer songs that have a bit more grit.

Your song ‘Scan the Beast’ from ‘The Tango Bar’ was noted for its political commentary. How do current events and the political climate influence your music, and can we expect similar themes in ‘Empire State’?

Every second of ‘Empire State’ is political in one way or another. Even the coyotes. We kept it short on purpose—make your point, paint your picture, and get out of the way. Never mind the blah, blah, blah.

At 77, your passion for music and storytelling remains strong. How do you stay inspired and motivated to keep creating new music?

Look around. All this beauty. All this turmoil. We’re a fucking snow globe.

Looking back on your career, what moments or achievements stand out as particularly meaningful or transformative for you?

I just turned 78, so I have no way to even begin to answer that question. Jerry Lee Lewis on American Bandstand? After that, you could pretty much take your pick.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Be kind. See what happens.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Chris Schmitt

Greg Copeland Facebook