Lee Michaels | Interview | “I have a bunch of stories”

Lee Michaels is a wild-eyed virtuoso whose Hammond organ wails like a tempest in a teacup, carving out a niche of raw, untamed soul that defies categorization.

His journey kicks off with The Sentinals, a band that sloughed off its surf shackles and slithered into the greasy groove of R&B, a metamorphosis that speaks volumes about Michaels’ audacious spirit. His career began with The Sentinals, a surf band that evolved into an R&B group, before he joined the Joel Scott Hill Trio, thanks to a recommendation from his lifelong friend Johny Barbata. Michaels later moved to San Francisco and joined an early version of The Family Tree, led by Bob Segarini, during a formative period in the city’s burgeoning music scene. His self-titled ‘Lee Michaels’ is a testament to his live prowess, recorded in a frenzy of spontaneity, while ‘Barrel’ was his self-indulgent romp in his very own studio, a place where rules bent and expectations broke. Despite his contributions as a session musician and his collaborations with legends like Jimi Hendrix, Michaels downplays his role in session work, feeling those musicians are far more accomplished.

His newest podcast brims with unfiltered stories, a barrage of hyperactive tales and vivid memories, offering a refreshing break from the somber, serious drivel that plagues the airwaves. Michaels’ career is a chronicle of thrilling unpredictability and fierce individualism, a rock ‘n’ roll odyssey fueled by passion and the relentless quest for the next great riff.

“I have a bunch of stories—boxing stories, music stories, stories of Venice, stories of my street.”

What inspired you to start your podcast?

Lee Michaels: We wanted to promote a movie that we had just finished making and decided to start a podcast to promote the movie.

How do you and your co-host Dylan Skye decide on the topics to discuss in each episode?

We just talk about stuff and decide. I have a bunch of stories—boxing stories, music stories, stories of Venice, stories of my street. I just decide what mood I’m in to tell what kind of story.

What has been the most surprising or unexpected aspect of hosting a podcast for you so far?

It takes up a lot of time. You’re only on the podcast for about thirty minutes, but somehow we waste four hours. It’s like having a job. I really enjoy it when I’m doing it, but the actual process of having a podcast is sort of like a job.

Reflecting on your time in the San Francisco music scene in the late 1960s, what were some of the most memorable moments or experiences for you?

Just being there—the whole thing was memorable. Every week, someone incredible was playing at the Fillmore or the Avalon Ballroom, and it was hard to decide which one to go to. What was most memorable was just being there to see all of those incredible bands.

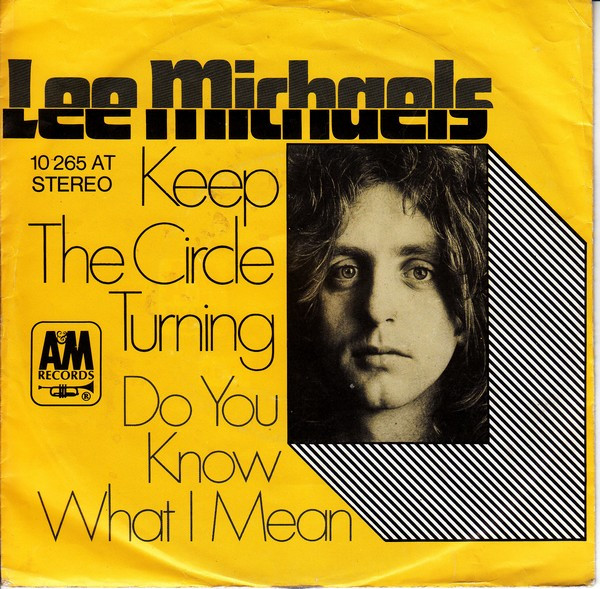

‘Do You Know What I Mean’ was a massive hit in 1971. Can you share any behind-the-scenes stories or inspirations behind the song?

I made the words up the morning before I sang it because I was trying to write a girl/boy song, trying to write a hit. It was originally released as the B-side to ‘Keep The Circle Turning,’ and someone flipped it over and made it the A-side. I didn’t have a clue; I was just trying to write a boy/girl song. Some people think that I don’t like the song, but I like the song. I just didn’t like singing it because the words were contrived and meant nothing to me, but I like the song.

With your music being a staple on classic rock stations, how do you feel about your songs continuing to resonate with audiences after all these years?

I don’t listen to those stations, so I’m outside of that loop, but I’m glad to hear that. Every now and then I’ll walk by someone doing construction listening to classic rock, and I’ll hear one of my songs and think, “Wow, I was there.”

From owning a successful restaurant to managing a boxing gym, you’ve had quite a diverse range of ventures. How did you transition from music into these different fields?

They were just acts of desperation and curiosity. With boxing, I love boxing, so I sort of fell into that one sideways. A friend wanted to be a boxer, and a friend’s brother wanted to be a boxer, so I said, “Oh yeah, let’s go do that.” I liked the characters and the whole scene.

Can you tell us more about your experience owning Killer Shrimp and how it has evolved over the years?

When I had it, there was only one item on the menu, and when my son took it over, he turned it into this monstrous thing it is now with all of these amazing items on the menu. He deserves the credit for what it is today; I deserve credit for starting it, I guess.

Managing a professional boxer must have been a unique challenge. What drew you to the world of boxing, and what lessons did you learn from that experience?

I learned that I had no business being involved in boxing. That’s what I learned. Boxing was great; I loved it. Every minute of it was fucking great. It’s an amazing sport. I can talk about it for hours, which I do on my podcast.

“Ideas come out of me like rapid fire”

You mentioned having numerous inventions. Could you share some details about your favorite or most successful inventions?

My latest invention that I just thought of is a self-service guillotine. I haven’t built it yet, but that’s my latest invention. Ideas come out of me like rapid fire; every day I’m thinking, I could do this, I could do that, I could be this, I could be that. You could only use a debit card, not a credit card, because you won’t be there to pay your bill.

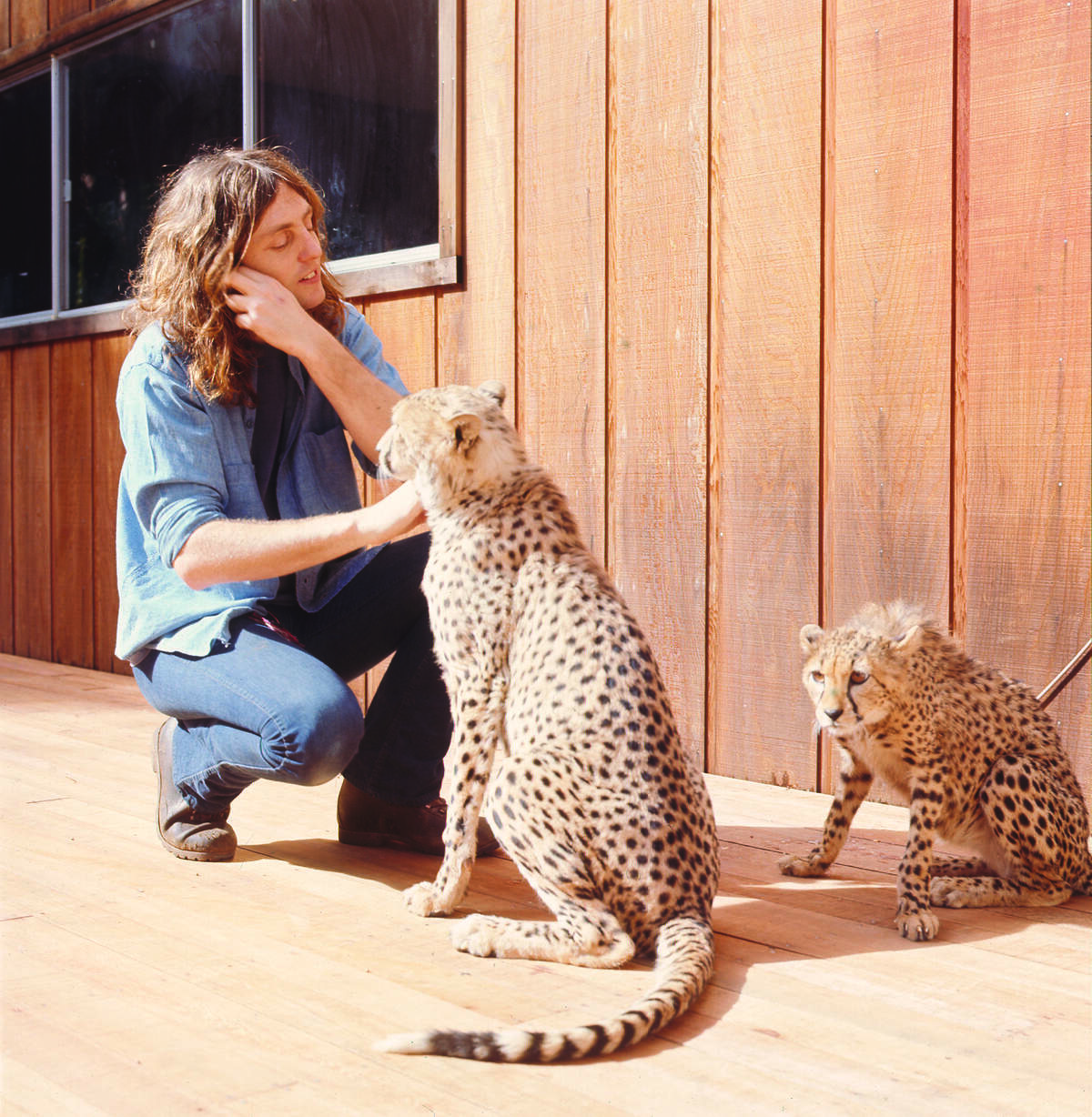

Owning exotic cats like tigers and cheetahs is certainly unconventional. What led you to keep these animals as pets, and what were some of the challenges and rewards of having them?

I’ve loved cats since I was a little kid, so since I love cats, it was natural to get bigger ones because I had the opportunity to do it. It was really fun, but the most memorable part of it was how much they ate because we had seventeen of them at one point, and imagine one of them could eat hundreds of pounds of food—so imagine how much food seventeen of them could eat. And then a lot of shit too; they shit about equal to how much they eat, and their piss is like toxic. It started out as fun, but later it got so out of control it was just a big fucking insane trip. I loved the cats; they were cool, and luckily no one got killed or too injured.

Looking back on your career and life so far, what would you say has been the most fulfilling aspect for you?

Seeing my kids. Because I was adopted, you know, so I never saw anybody I was related to. When I saw my kids, I thought, “Fuck, these guys look like me, I look like them.” It was profound for me. Before that, I was like a mindless reptile; I didn’t look like anybody, I didn’t feel like I belonged to any tribe. Then I saw my kids and I realized, okay, I’m part of something. That’s it for me; that’s my most meaningful experience.

Is there a particular story or anecdote from your podcast that stands out as a favorite or particularly meaningful to you?

I like all of them. If you look at the one called “Girl Fight,” that’s really good. It just depends on what you like; there are some good boxing ones, there’s one about stealing the Doors’ helicopter that’s kind of fun, and there’s one about the Palm Springs Pop Festival that’s fun. There are some fun stories. The idea of the podcast was to have fun. Every time I turn on a podcast, everyone is so serious, sitting and talking about all of this serious shit, and everybody’s so angry. So I’m less angry, I guess, and less serious as well. I’m trying to have fun on the podcast, so we’re not talking about politics or religion because we want to have fun. I feel like some fun is needed right now, at least in my life.

How do you envision the future of “The Lee Michaels Podcast” evolving, and what are your goals for it going forward?

I don’t know; the more it gets like a job, the more it gets like a job. I’m going, “Wait a minute, this is like a job,” so we’ll just do it as long as it’s tolerable. I really enjoy doing the podcast a lot and I love telling the stories, so hopefully, somebody likes hearing them. But mostly, I’m telling them so my kids and my grandkids will know my stories. They’ll see who I am, what I am, how I think, and then they can decide for themselves who I was.

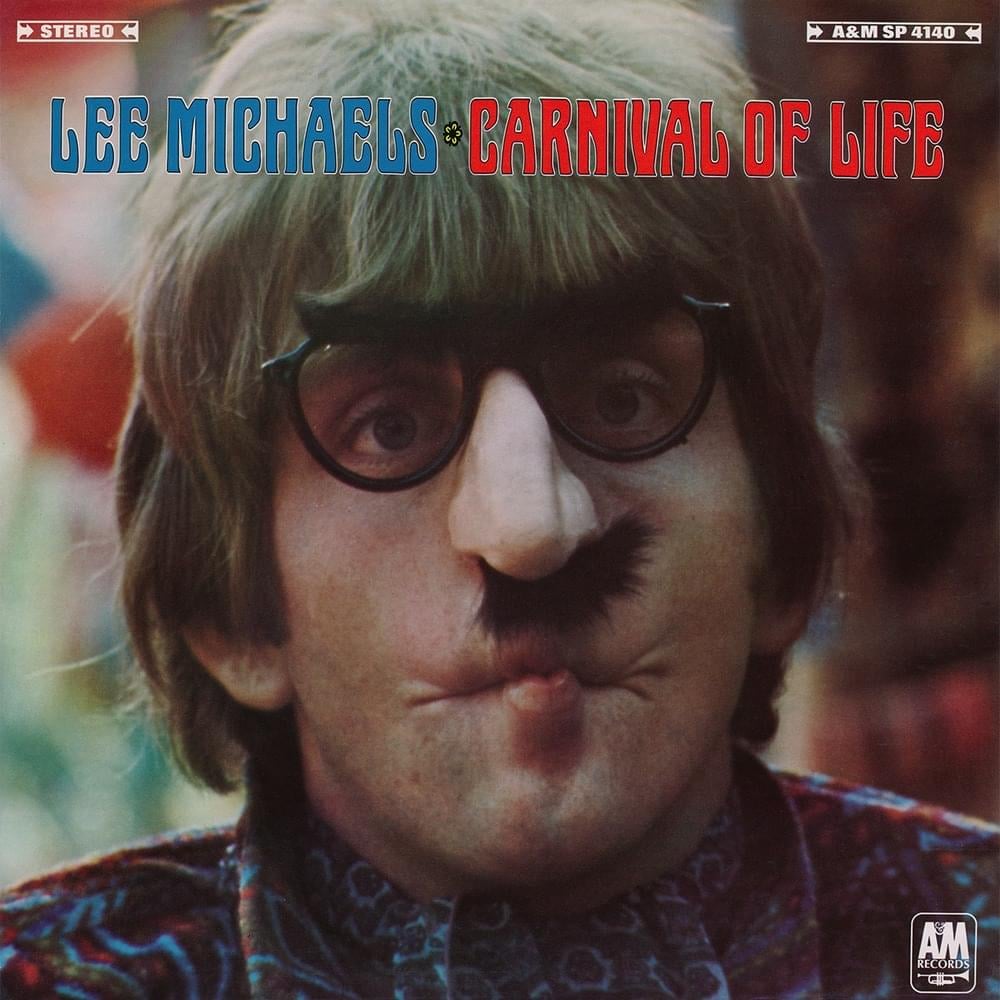

Your debut album ‘Carnival of Life’ is often regarded as a pivotal album in your career. What inspired the musical direction and lyrical themes of this album?

On ‘Carnival of Life,’ we just went in and played as a band. That album was how we played live.

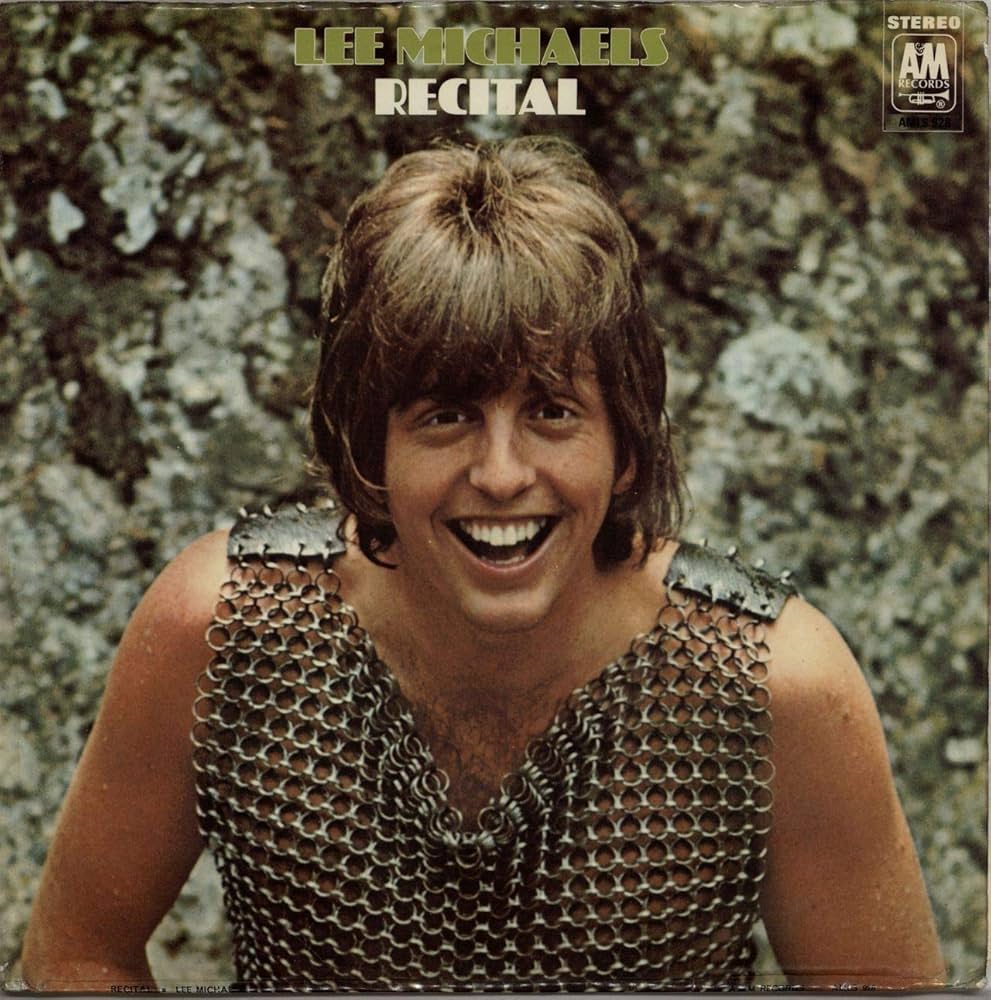

Your second album, ‘Recital,’ showcased your skills as a musician and songwriter. Can you take us back to the making of this album and share any memorable moments or challenges you encountered during the recording process?

That album was the first time that I got to do what I wanted to do. I got to go into a studio and fuck around and do stuff, so that was really a lot of fun, and I learned a lot. It didn’t do that well, and A&M didn’t like me side-tripping like that. They said that I spent too much money on that album.

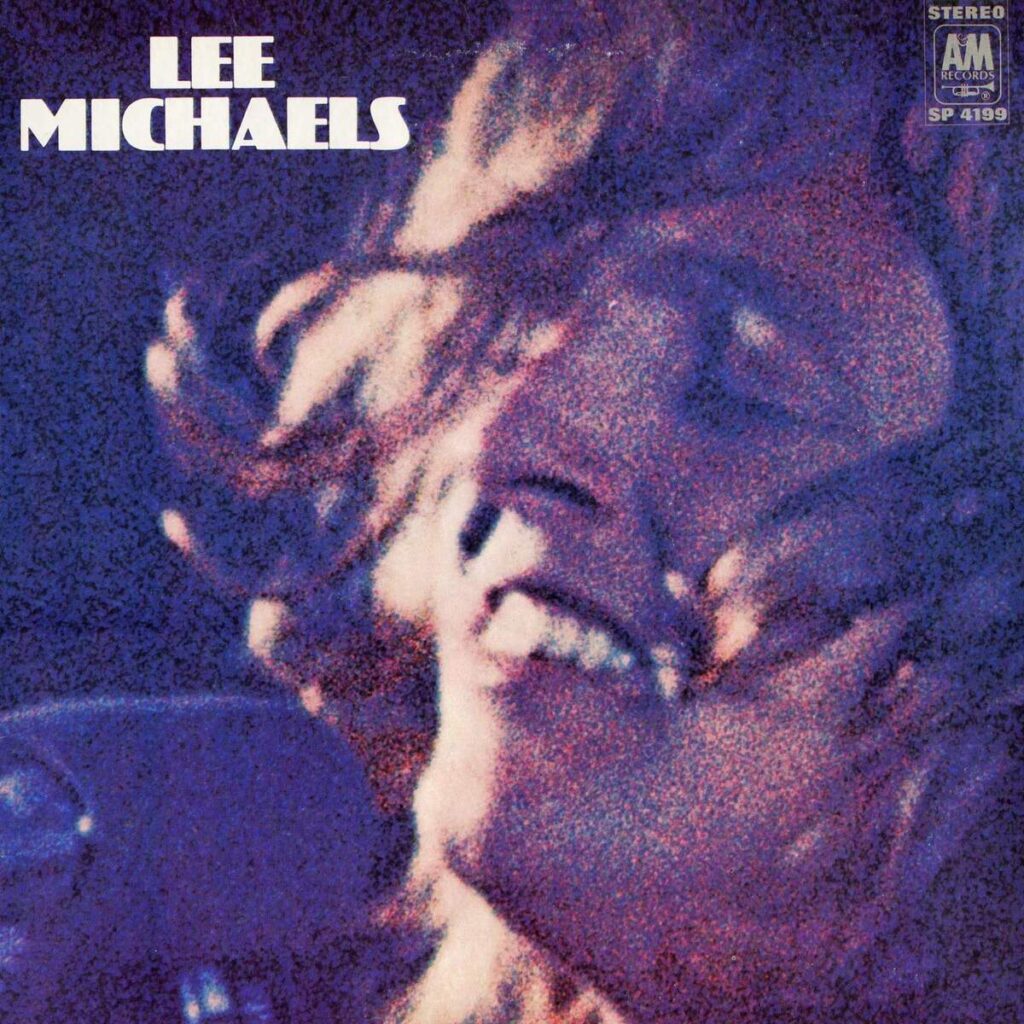

Your self-titled album, ‘Lee Michaels,’ continued to showcase your versatility as a musician and songwriter. How did you approach the songwriting and recording process for this album, and did you experiment with any new musical techniques or styles?

That album was our live set. Once again, we went into the studio and recorded that album in just a few hours—literally, just a handful of hours. It wasn’t an experimental record; it was just us going into the studio and playing our live set. That album was an honest album because that’s exactly how we played.

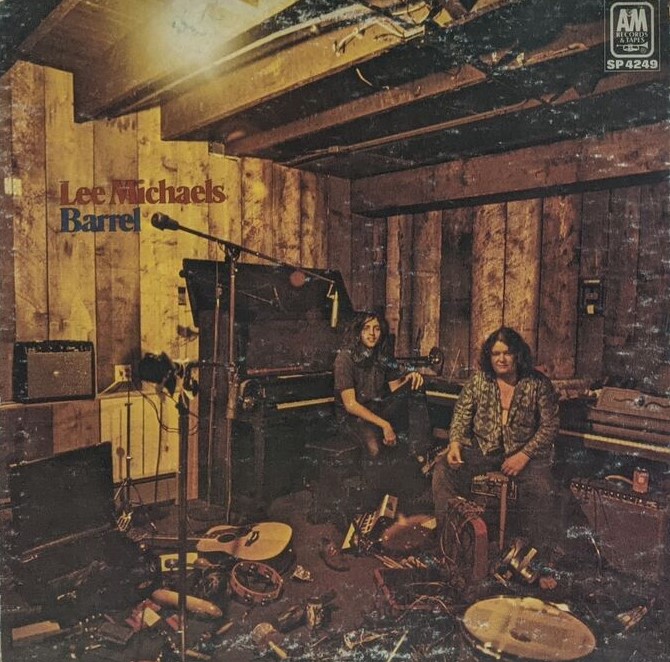

What about ‘Barrel’? The album features tracks like ‘Tell Me How Do You Feel,’ which showcase your soulful vocals and Hammond B3 organ skills. Can you discuss the process of crafting these tracks and the musical influences that inspired them?

‘Barrel’ was another experimental album where I had my own studio and got to record in my own studio and do what I wanted. It was sort of self-indulgent, and once again, it wasn’t that successful, and the record company wanted me to try to be more commercial.

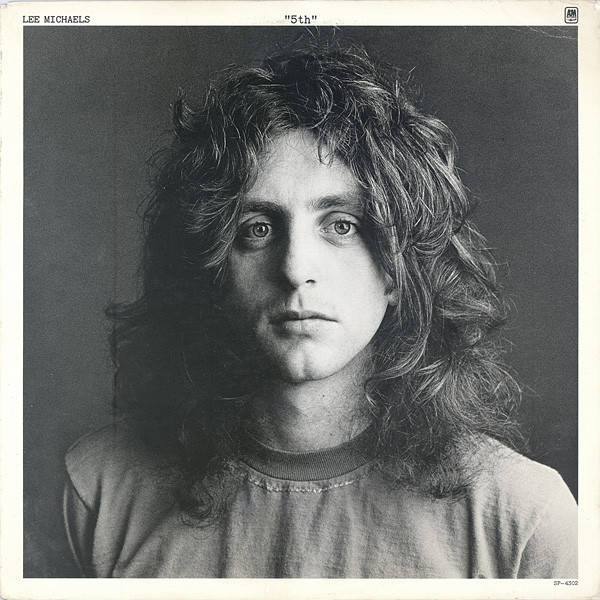

‘5th’ was released in the same year as your hit single ‘Do You Know What I Mean.’ How did the success of the single influence the creation and reception of ‘5th,’ and did it impact the creative direction of the album in any way?

It was simultaneous. The album was finished, and ‘Do You Know What I Mean’ was the B-side of the single released off the album, which was ‘Keep The Circle Turning,’ written by Joel Christie.

You began your career with The Sentinals, a surf group based in San Luis Obispo. Those were different days, right?

When I was in The Sentinals, they were a surf band trying to become an R&B kind of show band. They were already doing their R&B thing when I met them, so they liked what I was doing and asked me to join their band, but they weren’t a surf band at that point.

What was it like working with Johny Barbata, who later joined The Turtles and Jefferson Airplane?

John is a lifelong friend of mine; we’ve been friends since we were kids. I had to meet his parents to join his band—that’s how far back I go with Johny. Anyway, I love Johny.

After The Sentinals, you joined the Joel Scott Hill Trio. How did this transition come about, and what was it like working with guitarist Joel Scott Hill?

Johny got the gig with Joel first and kept telling him he knew about this organ player. Joel saw me playing organ somewhere and told Johny to forget about his friend because he found the new organ player. Then Johny told him that I was the friend he was telling him about, and that’s how I wound up in that band—thanks to John Barbata.

You later moved to San Francisco and joined an early version of The Family Tree, led by Bob Segarini. What was the music scene like in San Francisco at that time, and how did it impact your musical style?

That was when the first gigs were being held at the Longshoremen’s Hall, and Bob Segarini was some songwriter kid from Stockton and was somehow in with Autumn Records. This was before I did anything; this was right out of high school. We could drive to San Francisco in an hour and a half from where we lived, and we would go over there, sleep in our cars, and do whatever. That was right at the start of the whole thing. There was no Avalon Ballroom and no Fillmore at that time.

What are some of your standout memories or experiences from your time with The Family Tree?

There were none because we were just kids out of high school, and it wasn’t like a band that played any gigs or anything. I think we did an audition for Autumn Records, but it was basically us playing Bob Segarini’s songs because he was a songwriter. I was just an organ player.

Your choice of the Hammond organ as your primary instrument. What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style, and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

There was a guy in Merced, California, in a band called the Merced Blue Notes; his name was Bobby Hunt. When he bought a Wurlitzer piano, I bought a Wurlitzer piano. We used to hide outside the rehearsal hall to hear them because they were so good. He was a big influence on me, and when he bought an organ, I bought an organ. Of the famous jazz players from back in that era, I liked Jimmy McGriff. He was probably my favorite organ player; I liked the way he played. I was never a big fan of Jimmy Smith. It seemed like he was head-tripping, trying to play all of these chords. I felt McGriff was more down-to-earth.

Frosty, known for his barehanded drumming technique, was a frequent collaborator. How did his unique drumming style complement your organ playing, and what was the creative dynamic like between the two of you?

Frosty and I played well together from the second we started playing together. You know how it is; you play with some people, and it just clicks—Frosty and I clicked. You should go back and check out the podcast where I talk about how I met Frosty; it’s a great story.

“The times I played with Jimi Hendrix were fun”

As a session musician, you had the opportunity to play with legends like Jimi Hendrix. Can you share some insights or stories from your time as a session musician and how it influenced your own music?

I was never a session musician; those guys are light years ahead of me and are immensely talented. I would never call myself a session musician, but the times I played with Jimi Hendrix were fun. On my podcast recently, we did a whole segment on my experiences with Hendrix.

Thank you for taking your time. The last word is yours.

Listen to my podcast if you want to hear some stories. I tell stories; I like telling stories, so it’s fun. I’m so hyper, so if you like hyper storytelling, check out my stuff.

Klemen Breznikar

Very special thanks to Dan Perloff and Josh Mills.

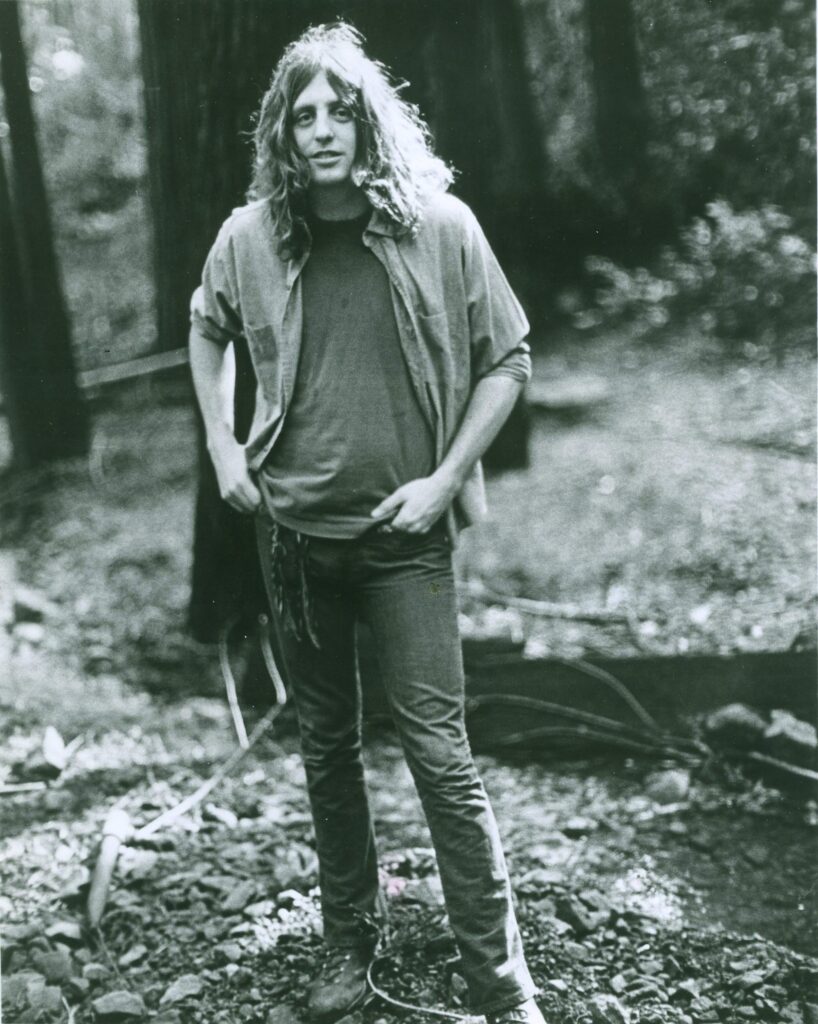

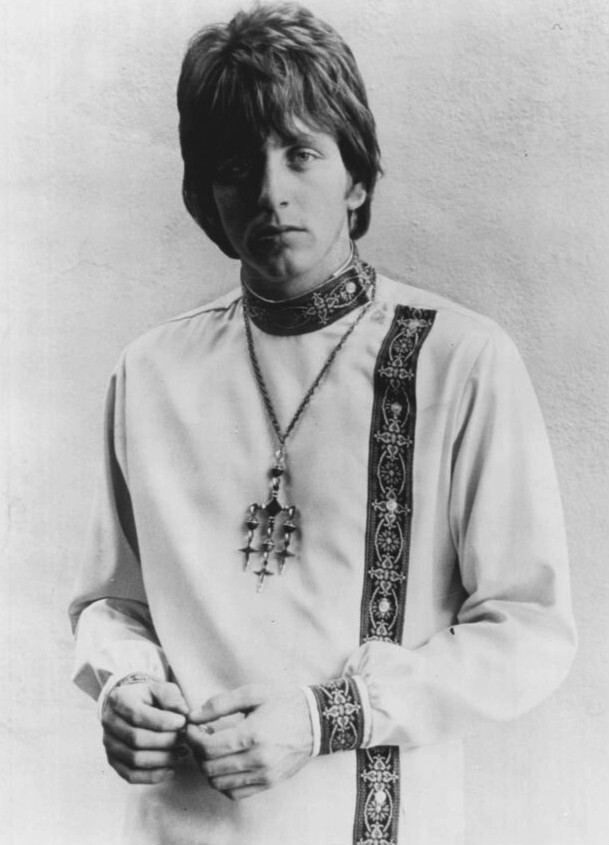

Headline photo: Lee Michaels | Photo by Jim McCrary

Lee Michaels YouTube

lee why did you give up making albums?

so sad we all get older, I wish we could go back and stay there,

The podcast is very entertaining. Lee does not really like talking about his albums, so you were lucky to get that info out of him.

Bought a guitar from Lee’s manager. Told him I loved Frosty’s drums. He said the recordings may saw Frosty, but Joel Larsen did the studio recording.

Lee

Thank you Brother; I was 11 when I heard your song. I’m fuckin 66 and the song still maintains its groove. Thanks again, Love ya Brother.

I emceed his concert in portales New Mexico at the university in the early 70s I emceed his concert in portales New Mexico at the university in the early 70s. He was very arrogant and standoffish I like him better now

I heard a concert you did at the Anaheim convention center summer of 69′ ,you ran through a medley of songs from recital but no songs like Grocery Soldier separately why ? The opening act w as Ike and Tina Turner review .I heard IkeTurner was an asshole but Tina was very cool, Lee Michaels and Tina Turner would have sounded soo fucking Great even though it’s too late what do you think of a collaboration?