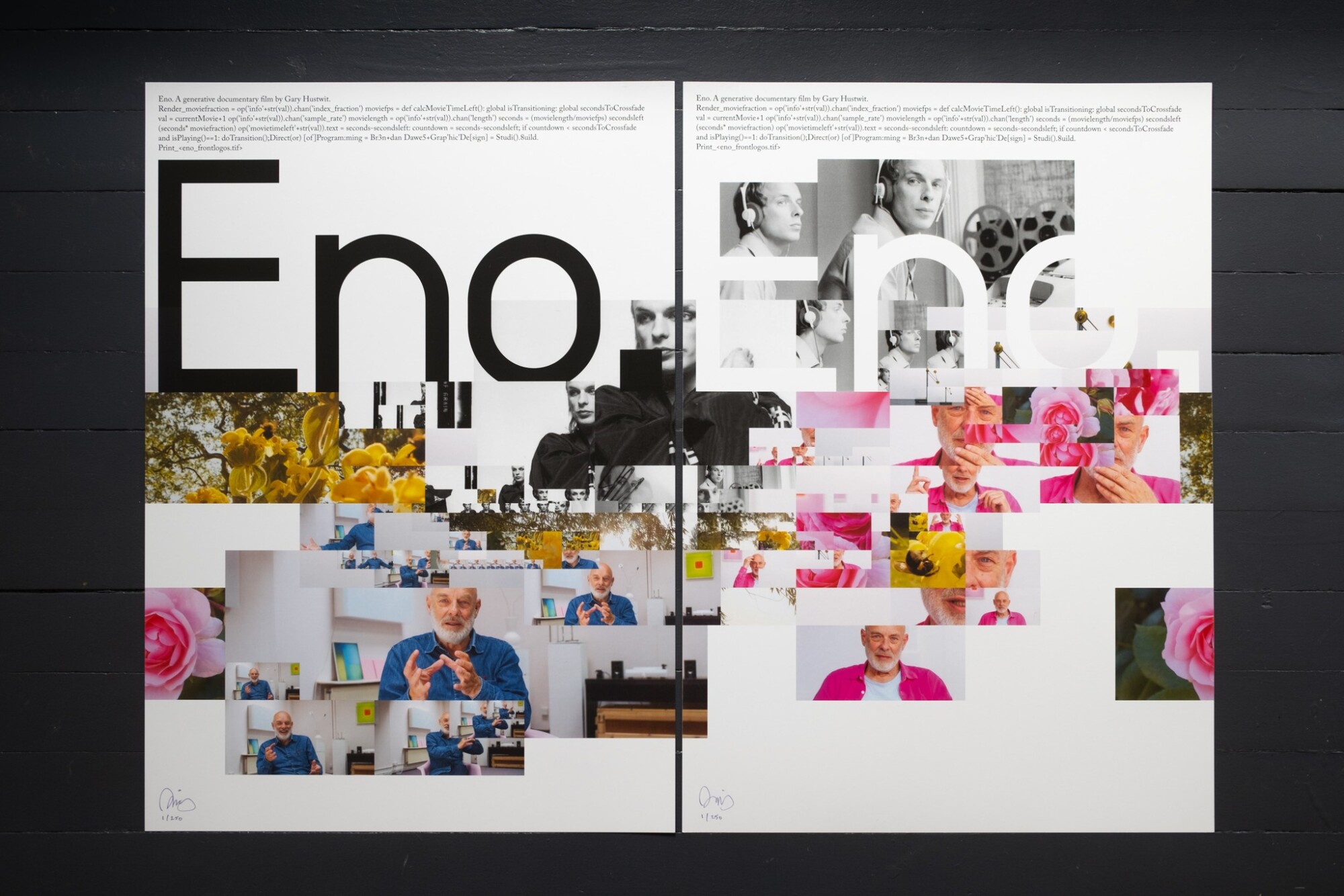

“Eno” (2024) by Gary Hustwit —A Review

After the premier at Sundance Film Festival in January of this year, the new documentary about the British musician, producer, and artist Brian Eno went on its world tour. For each screening, advertised as “never to be seen again,” the footage is reordered by the software, thus making each presentation somewhat unique. The alleged “first generative film” features much of the archival footage that a viewer may find elsewhere. Yet the work also includes not previously seen interview scenes with Eno in his home studio.

A Cutting-Edge Generative Film-Making?

Regarding the “generative” catchphrase, while I realize, based on Q&A, that the audience on average gets impressed by the unique assemblage of footage, unique for each screening, to me the approach appears to be trivial to the extent that makes me wonder why it wasn’t employed as early as in the 1950/60s when algorithmic techniques were introduced in the art-making process. [1] Long story short, the generative profile of the film is as follows: about 10 hours of footage from which in a collage manner the software designed for the film selects segments for about 85-90 min of screening. There are a few pre set elements of the film that are not affected by the “generative” algorithm – the beginning and ending of the documentary. While the footage segments’ being grouped by the software introduces the element of non-linearity in the narrative, the development still follows certain plot prompts pre set by the film director and the team. Such are the oblique strategy cards, for example.

Oblique Roots and Influences

On the intersection of structure/technique and content/message areas lays another issue: the film inevitably features all elements of the conventional narrative that Brian Eno shares when talking about his work; the film includes all conceptual milestones one can absorb by listening to a few interviews of Eno or reading his Wikipedia page. In other words, the film doesn’t open up a new angle on Eno’s work other than what he himself already manifested. . .over decades. For example, have you ever wondered about the place of Eno in the landscape of experimental music? Did you want to learn his positionality with respect to minimalism? The genealogy, if you like. Eno is a kind of an artist who derived from the tradition of American experimentalism, just as John Cale [2] – who’s featured in the film. In his earlier interviews, Eno noted the impact of Terry Riley. In the film, he also talks quite a bit about repetition and slow listening. Why not dig into the subject? In “Eno” the artist is solely mapped within the mainstream music – and a viewer gets exposed to what’s already known about Eno’s work with Roxy Music, U2, David Bowie, etc. On the same page, why other 20th-century experimental art is used for contextualization? For example, the land art is not brought up at all – despite the presence of the scenic shooting of the landscapes/bird eye view scenes accompanied by Eno’s thoughts about our place on Earth.

Eno as a Thinker – A Man of His Time

In this part I would like to discuss less of the film features but the overall paradigm of Eno’s creativity and his thinking about music in particular.

The first thing to note concerns the compositional process. Since right now an experimental composer of similar influences is writing a book about propositional music, reinventing the wheel, I would like to highlight that what’s to be theorized in that book has been already grounded in the approach of other musicians and in no way is an “invention.” Brian Eno is working in a “propositional” paradigm if you like. [3] Specifically, throughout the documentary Eno discusses his fascination with the complexity theory and nature, and how he applies what he notices in nature in his creative process. The metaphor of “gardening,” and there’s much of Eno in the garden footage in the film, works well to describe his approach. Setting a set of rules, Eno creates a potential for self-organization and the rise of complexity in his art-in-making. Rather than acting as an “architect,” setting up a composition, just as a concrete building, he attempts to “plant” the “seeds” of further evolution of a piece. He’s sculpting a music piece or art to the extent necessary for future autonomous generations – somewhat seeing his pieces as the open systems that may be affected by listeners, performers, and other actors – in a way that may be generative and provide surprising results.

Secondly, Eno talks a lot about creating environments of exploration, (the “propositional music” theorist stamps the same idea), and making the atmospheres of sound. This focus on the atmosphere and the soundscape illustrates that the film is missing the important parts of Eno’s musical genealogy. It would be more than helpful to draw a connection between Eno’s view and the thoughts of J. Cage, J. Attali, and R. M. Schafer – to name a few theorists of sound art and acoustic ecology.[4]

Speaking of imaginary landscapes, [5] Eno develops his thoughts about ambient music using the same ideas and elements as the beloved pioneers of minimalism. Eno goes on to talk about his experience of watching the Apollo mission in 1969 and the impact it had on him. That experience motivated his decision to create music for the film “For All Mankind” (1989), [6] and the work on the soundtrack led to the conceptualization of the ambient. The artist was interested in “stillness”, almost close to nothingness – the absence of sound, and he tried to work with it creating a “floating” quality of sound – inspired by his observation of nature, (imitating rivers flowing), and the flow of the spaceship. He describes the kind of listening enabled by ambiance as “watching the auditory system in operation,” thus demonstrating his intuitive comprehension of the “brain “seeing” patterns.” By that, I think, he means what neuroscientists call evoked potentials. [7] This line of reflection proceeds with Eno acknowledging the influence of cybernetics, in particular, reading the article of W.S. McCullough et al. “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain” (1959). Eno sees that in perception of the world and the art forms we are basically “filtering” landscape, based on our past experience or other circumstances.

Thirdly and lastly, I can’t avoid mentioning the keyword to Eno’s work – SURRENDER. As Eno theorizes, we, humans, seem to enjoy most the moments of surrender, somewhat a dissolution of ego, (hippies used the same phrasing), in something greater than oneself. The experience of surrender may occur to us in four kinds of situations, according to Eno: religion, sex, drugs, and art. Listening to music in a group situation, as he points out, we approach that kind of dissolution of self and the sense of unity with a whole. He calls it tele-pathy, referring to the synchrony in feeling with other people, the capacity to approach their emotional state without a direct interaction. For some evolutionary reason, Eno meditates, we enjoy what he calls “surrender” more than anything, and he sees his practice of artmaking as “creating situations where people can have feelings.” The concept of surrender is also well applied to thinking of human interaction with nature. Eno suggests that just as in the relationship of humans with their environment, unless taking a strategy of conquer & exploit, through art we can enjoy uncertainty and confusion – emerging out of the interaction of complex systems, [8] and one of Eno’s creative goals is to share this appreciation of uncertainty with his audience.

Concluding, even if you are a great fan knowing close to all about Brian Eno, I think the film fulfills the mission of summoning the thinking of Eno, and his understanding of his own creativity. Given that Eno is an original thinker worth keeping an eye on, whether you like his music or not, the film is undoubtedly informative and inspiring. Check it out if the screening comes to your town. For the schedule refer to the director’s page.

Written by Anastasia Chernysheva, a PhD. student at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and a Visiting Graduate Researcher at UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music.

References:

[1] Wright, R. (1960). From system to software: Computer programming and the death of constructivist art. White Heat Cold Logic: British Computer Art, 1980, 119-139.

[2] Potter, K. (2016). Mapping early minimalism. In The Ashgate research companion to minimalist and postminimalist music (pp. 19-37). Routledge.

[3] Rosenboom, D. (2003). Propositional music from extended musical interface with the human nervous system. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 999(1), 263-271.

[4] Bartle, B. K. (1977). The tuning of the world. Journal of Research in Music Education, 25(4), 291-293.

[5] Cage, J. (2012). Silence: lectures and writings. Wesleyan University Press.

[6] Eno, B., Lanois, D., Eno, R., & Reinert, A. (1983). Apollo: atmospheres and soundtracks. Virgin.

[7] Sutton, Samuel, Patricia Tueting, Joseph Zubin, and E. Roy John. “Information delivery and the sensory evoked potential.” Science 155, no. 3768 (1967): 1436-1439.

[8] related terms are systems dynamics and chaos theory.