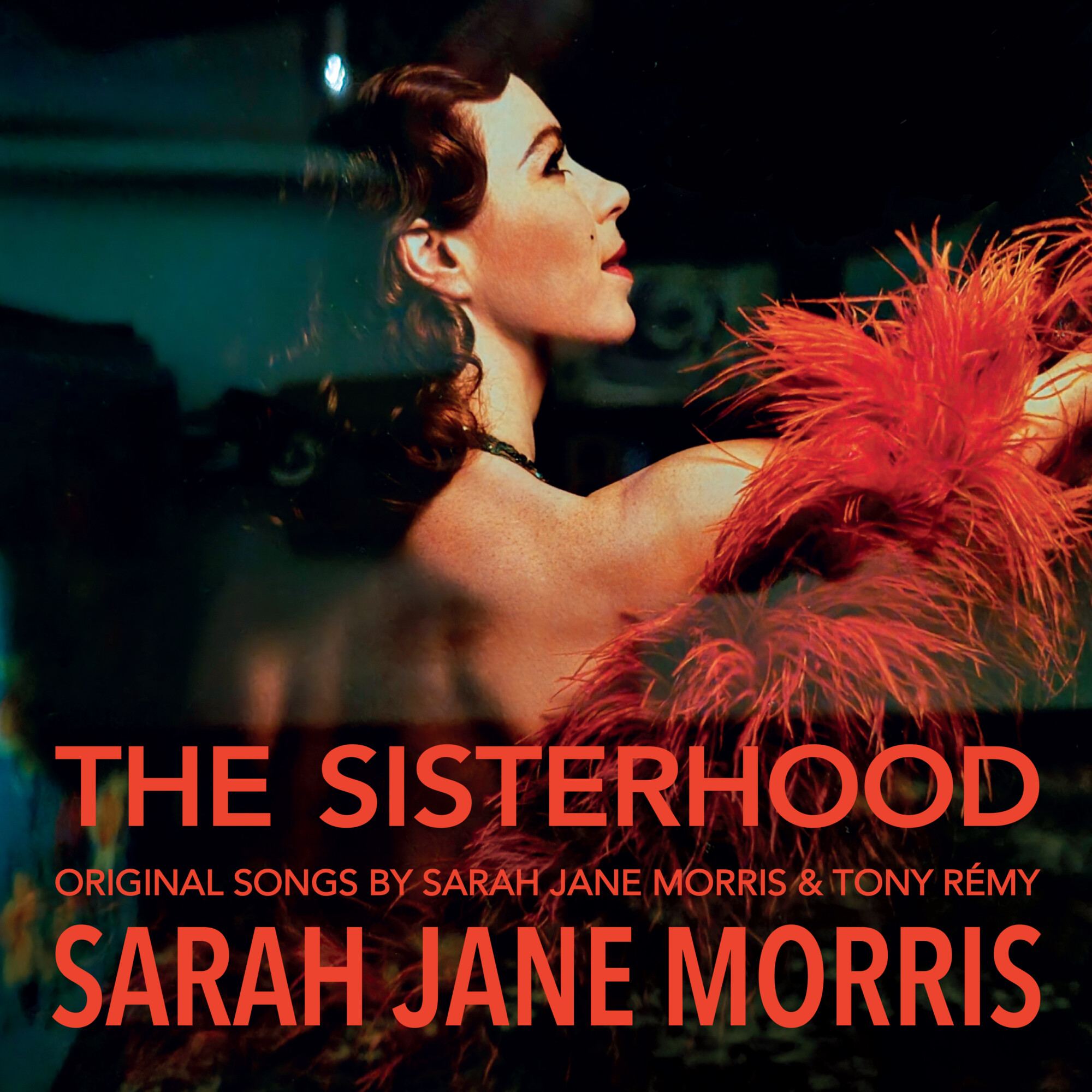

Sarah Jane Morris | Interview | New Album, ‘The Sisterhood’

Sarah Jane Morris’ ‘The Sisterhood’ is a heartfelt tribute to ten iconic female stars who shaped 20th-century music.

Through months of lockdown, she and her husband Mark meticulously crafted lyrical structures, infusing each track with contemporary relevance while honoring the legacies of the original artists. Despite challenges, Sarah Jane’s dedication shines through, resulting in a collection that celebrates the resilience and artistry of women in song. Beyond its musical brilliance, ‘The Sisterhood’ is a testament to Sarah Jane’s evolution as an artist and her unwavering commitment to social and political commentary. In essence, it’s a labor of love—a triumphant celebration of sisterhood and the enduring legacy of female musicians.

Sarah Jane Morris embarked on her musical career in 1982 as the lead singer of The Republic, a London-based band that garnered attention from the music press but struggled to secure radio play due to their political themes. Transitioning to The Happy End, a brass band, Morris explored protest music and her theatrical side with covers from Brecht/Eisler and Brecht/Weill. Finding fame with The Communards, her distinctive low vocal range juxtaposed Jimmy Somerville’s falsetto on hits like ‘Don’t Leave Me This Way’. Since then, she has pursued a solo career, releasing albums and collaborating on various projects, including opera and albums like ‘Sweet Little Mystery’ with guitarist Tony Rémy.

“There are many more female singer-songwriters who deserve to be celebrated”

‘The Sisterhood’ celebrates ten iconic female singers who left an indelible mark on the 20th-century music landscape. What inspired you to undertake this project, and how did you select the artists to honor on the album?

I found myself in the second lockdown wanting to do something that made the most of that downtime. I read a great deal as I don’t have a TV, and my husband and I read to each other. I asked him if he’d mind me reading him the biographies and autobiographies of female singer-songwriters that I felt had made a difference to musical history. I initially chose 50 singer-songwriters, and then once I realized this research could turn into an album, I stripped that list down to 10. By this time, I was seeing the project as a passing of the torch from generation to generation. There are many more female singer-songwriters who deserve to be celebrated, and whose stories are as fascinating as those we have told.

‘The Sisterhood’ is described as your “lockdown project,” conceived during months of isolation. How did the circumstances of the lockdown influence the creative process, and what challenges did you encounter while working on the album?

The pandemic was a very strange time for us all, but come the second lockdown I wanted to do something really creative with time so unexpectedly available. I run my own label and have done for 24 years so I finance my own projects. Brexit had already badly affected my earnings and so, of course, did COVID. Financing the project has called on a lot of creative thinking and relentless hard work. Once the lockdown was lifted and Tony Remy and I had written and demoed the songs, I set up a masterclass where 15 people would come to take part over a weekend, when I taught three-part backing vocals to four of my songs. The participants then came and sang at Ronnie Scott’s with us the following month. This provided the initial studio fee. We became Airbnb Superhosts with our spare room. I upcycled furniture and made clothes and cushion covers and tablecloths on a gifted sewing machine and sold them on Facebook Marketplace and eBay. I set up songwriting weekends and fine art weekends and it all generated a wonderful level of enthusiasm, generosity, and support. This allowed us to go to South Africa to record with The Soweto Gospel Choir on the day Miriam Makeba would have turned 90.

Each track on ‘The Sisterhood’ pays homage to a different female music icon. Can you share some insights into the lyrical and musical choices you made to honor each artist’s legacy while bringing your own unique interpretation to their work?

We thoroughly researched each artist’s life journey and stayed away from hearsay and gossip (except in the case of Bessie Smith, where we have allowed the legend to take over and scandal to spill into the lyrics). With Billie Holiday, I chose to write about her bravery to continually sing the song ‘Strange Fruit’ about lynching, in spite of the fact that the FBI tried to destroy her career because of it. They knew she had a heroin addiction so would sell her heroin undercover, then raid her dressing room: or plant it in the trunk of her car when they flagged her down. Her song is called ‘Junk In My Trunk’. Tony and I both said if she was around right now she’d be working with a hip-hop drummer, so we hired one for her track. With Joni Mitchell’s song, we were thinking of the music of her album ‘Hejira’ and both of us knew where to take it. Joni’s song is called ‘Sing Me a Picture’ and starts with her childhood fight with polio and then follows her as young, pregnant and penniless, knowing she would have no welcome anywhere with her baby. We link her experience of struggle and loss to her lifelong identification with those who suffer injustice and hardship. We also ascribe to her a kind of artist’s magic power of transformative imagination, with painting, music, dance, and poetry her fluid, multi-layered language of expression. With Rickie Lee Jones, her story was a gift to a songwriter and we have written about her one-legged tap-dancing grandfather, how she hitched around America from the age of 12, her relationship with Tom Waits and her broken heart. She wrote in her autobiography about being influenced by Van Morrison, so we deliberately echo Van’s lyrics with our chorus “Thumbing in the headlights on the jazz side of the road” which also provides the title. Rickie Lee wrote to me once her song was released as a single: “Sarah Jane Morris, thank you. You have gone right into my heart, like a convertible GTO at a drive-through car wash, except the top was down and everything got all wet. Mom’s gonna kill us. Tears today, lots of tears. Thank you for this truth. I dig it and I’m honored.” It doesn’t get much better than that!

“We approached each track differently”

Your album strikes a balance between contemporary sound and the classic styles of the artists you’re celebrating. How did you approach blending these elements to create a cohesive and modern musical experience?

We approached each track differently but because we have so many years of musical experience between us we knew where to turn each time. We got different keyboard players for most tracks although a lot was played by the incredible Jason Rebello, and different brass arrangers, and two string arrangers. The Soweto Gospel Choir presumed we had recorded Miriam Makeba’s track in South Africa rather than with our band in a studio in Eastbourne. It says a lot for the musicianship of my band and Tony’s deep understanding of African musical form and tradition.

Collaboration played a significant role in bringing ‘The Sisterhood’ to life, with Tony Rémy co-writing and co-producing the project. Can you tell us about your creative partnership and how it influenced the album’s direction and sound?

Once my husband and I had written the lyrics, Tony came to stay. He had his MIDI keyboard, Logic recording on his laptop, a good pair of headphones, and his acoustic guitar. I had a good microphone and a good set of lyrics to read to him. Once I started reading them we both simultaneously thought it would be good to write the music in the genre associated with the singer-songwriter, and in some cases found ourselves thinking about what the artist would be doing now if they were still alive. Writing with Tony is a totally natural thing to do. We know each other so well, as we have been writing and playing together for years and years. We are very close friends and totally trust each other’s musical instincts. I feel very lucky to have found the perfect writing partner. We make a very good production team too!

You mentioned that each song on the album tells a story that resonates with your own musical journey. Could you elaborate on how the stories of these iconic singers intersect with your personal experiences and artistic evolution?

My father went to prison when I was 17, which changed everything for me. I went to drama school at Central School of Speech and Drama, and we did an in-house production including Dawn French and Jennifer Saunders, Rupert Everett, and Julian Sands. My part in this was to sing some Blues, and I chose Prison Songs and discovered Bessie Smith. Miriam Makeba came to my attention when I was in The Republic and then The Happy End, as I joined Artists Against Apartheid, which had been set up by my friend Jerry Dammers and my then-boyfriend Dali Tambo. Mine became a Safe House in Brixton for South African musicians arriving in exile. I would be there most weekends outside South Africa House singing through a megaphone. Rickie Lee Jones’ ‘Pirates’ became the backdrop to my 20s and my most played vinyl. The stories are too numerous to include them all.

As an accomplished vocalist with a rich contralto range, you’ve become known for your emotive and expressive singing style. How did you approach interpreting the songs of these legendary artists while bringing your own vocal identity to the forefront?

I never tried to sing like the artists we wrote about in our songs for them; I was instead telling their stories through song. The exception is ‘Junk in My Trunk’ where my background in drama allows me to be Billie for the choruses. I’ve often been compared to Nina Simone and Janis Joplin and nearly played Janis in two different movies. Jerry Ragovoy, who wrote ‘Piece of My Heart’ which was Janis’s first huge hit, said that I was the nearest thing to Joplin he had heard, after hearing me sing it at Ronnie Scott’s. He suggested I played her in the Paramount movie that was about to be made. An interesting fact is that Jerry collaborated with Makeba on her definitive version of Pata Pata, the English version, which became a worldwide hit.

You gained prominence in the 1980s with bands like The Republic, Happy End, and The Communards. Could you share some further words about the three mentioned bands and what it was like working on those recordings?

The Republic was very important in my musical career as it introduced me to African-Caribbean-Latin music that I hadn’t encountered before. John Glyn and Tim Fienberg were such a strong songwriting double act, with the occasional lyrics by John Matchikiza, my acting friend, whose family were in exile in the UK, due to his father having been part of the writing team of King Kong the musical, that brought Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela to London. The band was on the cover of NME, City Limits, and a documentary was made about us by Granada TV, and we were signed to Charlie Gillet’s ‘Oval Records’. Alas, we were deemed too political for the airwaves and after a matter of years, we split up. Some of us went and joined ‘The Happy End’, a 25-piece big band that made politics swing, and the other half teamed up with 3 Mustaphas 3. The two band leaders and arrangers of The Happy End, Matt Fox and Glen Gordon, are sadly no longer with us, but they introduced me to wonderful political music from all over the world. We had a South African Township section and a Chinese section as well as Irish Music, Chilean Music, Spanish Civil War music, and of course the music of Hans Eisler and Kurt Weill. I met Jimmy Somerville during the Happy End period as Richard Coles, a long-term friend, brought him to meet me at a Happy End gig. We both got on instantly and joked about the role reversals with him being the redheaded man with the high falsetto voice and me being the redheaded woman with the baritone voice. We had a year of touring the world and had our big hit duetting together. We are still good friends and live within an hour of each other on the East Sussex coast. All three bands have been very significant in my musical career and development.

Looking back on your extensive career, where does ‘The Sisterhood’ rank in terms of personal significance and artistic fulfillment?

For me and for Tony too, ‘The Sisterhood’ has been a very special project. Everything in our musical histories leads to this mutually taken path. All of our expertise and experience are deployed. We are both probably at the peak of our powers, and have tackled the most demanding and wonderful musical challenge we have ever set ourselves. All that we have learned over these years can be found in this album. It has become our overriding passion. Art does that to the artist. It makes obsessives of us, backing our gamble with everything we’ve got.

What are some future plans?

‘The Sisterhood’ is a complex, ambitious project which requires the full band including keyboards, brass, and backing vocals plus technicians. My major ambition for the project is that it can develop in live performance. If I can take this project on the road with the full company, that would take care of the artistic kickback. Six of the ‘Sisterhood’ are from the US and Canada. I would like to take it to North America and renew contact with my audience there. Also, it would give me profound satisfaction to sing Mama Africa’s song with the Soweto Gospel Choir in South Africa.

Thank you. The last word is yours.

There are so many more stories to tell. We are still writing. Watch this space.

Klemen Breznikar

Sarah Jane Morris Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / YouTube

I’ve just discovered you On YouTube…absolutely incredible voice and performance. Phenomenal.