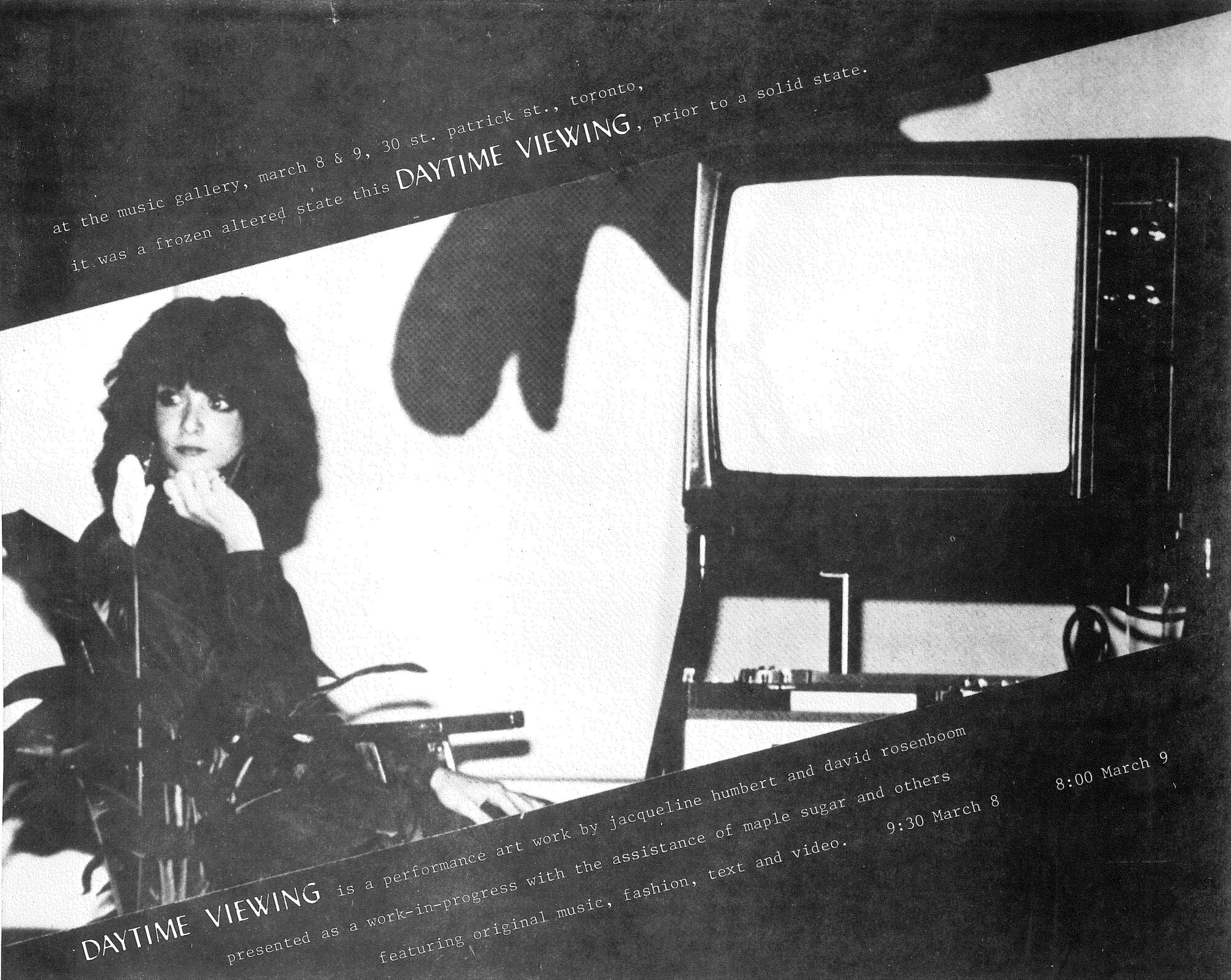

David Rosenboom | Interview | ‘Daytime Viewing’

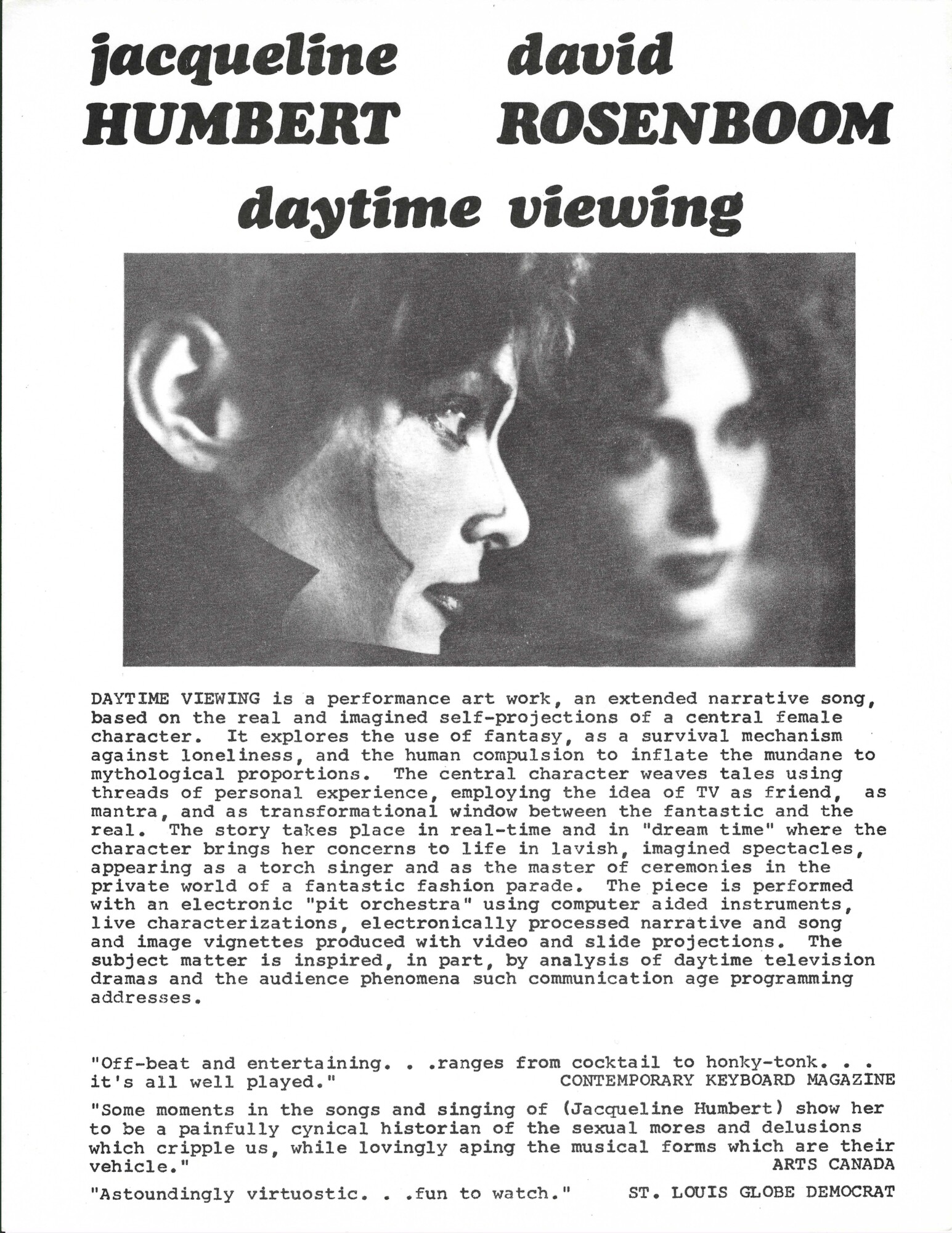

‘Daytime Viewing (1979-80)’ by Jacqueline Humbert & David Rosenboom is an extended narrative song, based on a causal analysis of daytime television drama and the audience phenomena such programming addresses.

Unseen Worlds recently issued 40th Anniversary Edition – newly remastered from the master tapes, with an additional bonus LP of instrumentals and the previously unreleased ‘Narration Theme.’ The piece explores the use of fantasy as a survival mechanism against loneliness, illustrating the human compulsion to inflate the mundane to mythological proportions. A central female character weaves tales, using threads of personal experience and the idea of TV as friend, as mantra, and as transformational window between imagined spectacle and the pedestrian plane. Originally released as a private cassette edition [recorded, 1982; Chez Hum-Boom release, 1983] documenting the collaborative performance piece of the same name by Jacqueline Humbert & David Rosenboom. This heady, thoroughly enjoyable work was first made available on CD and LP in 2013 by Unseen Worlds. Jacqueline Humbert (aka J. Jasmine) is a songwriter of brains and wit on par with Robert Ashley, with whom she’s worked extensively. David Rosenboom’s complex, harmonic electronic arrangements are accentuated brilliantly by percussion from William Winant.

“Media intoxication, brainwashing, amplification of nefarious actors and all their deleterious effects are challenging human beings’ ability to maintain independent emotional identities”

The Unseen Worlds recently issued a re-release of the ‘Daytime Viewing,’ a 1983 album you did with Jacqueline Humbert. What will be the main difference from the first edition?

David Rosenboom: All the tracks have been remastered by Stephan Mathieu with the best quality ever. They sound wonderful, both Jacqueline Humbert’s voice and all the instrumental sounds. The new edition includes three new instrumental tracks that have never been released before, ‘Narration Theme,’ ‘Talk 1 Instrumental,’ and ‘Talk 2 Instrumental (Clear Light Beat)’. I made these tracks from tapes we created back in 1979-1980 for theatrical versions of ‘Daytime Viewing,’ which we presented prior to making the studio recordings that were first self-released on cassettes and then finally released in such wonderful packages from Unseen Worlds. Finally, the new vinyl package includes a beautiful booklet showing some of the gorgeous visual materials that were also created for the theatrical performances.

How do you envision the audience of the album? What is your image of a potential listener?

I have been continuously surprised by the broad range of listeners who have enjoyed ‘Daytime Viewing’. So, it’s difficult to narrow down a description of the audience for the album. I’ve heard from listeners of all ages and from walks of life I might never have expected. I’ve been really gratified by how many young people have responded to the music. I teach at CalArts, of course, and I hear again and again from students who have heard the music and want to know more about its meaning and how it was produced. By the way, I recently notated the songs in scores that can be downloaded from my website here. Before this, I performed the material from hand-written, manuscript scores that were fully comprehensible only to me. Now, others can enjoy the notated versions of the music as well.

Now I would like to talk about the conceptual aspects of the recording. Do you find the themes and issues captured in the lyrics in the early 1980s to be still relevant in the 2020s?

Yes, they seem to be. I say that because people are responding to the range of sociological issues ‘Daytime Viewing’ explores in the context of present-day society. Among other things, ‘Daytime Viewing’ examines psychological terrain resulting from being absorbed in television media as an alternative landscape, ensnaring people’s emotional, familial, and social dynamics. Today, we struggle with another landscape overtaking humanity, social media and the Internet in general. Media intoxication, brainwashing, amplification of nefarious actors and all their deleterious effects are challenging human beings’ ability to maintain independent emotional identities and mental agencies amid the storms of sketchy delusional fantasies constantly bombarding us online. ‘Daytime Viewing’ is still striking resonant chords with people facing all these challenges and psychological issues of our present time, I think.

“I don’t think about genres”

It’s hard to map the album genre-wise. Especially, perhaps, since you used a unique musical instrument to compose it. With respect to the sound – do you find the way tracks sound to be contemporary? Would you say that the use of Touché makes it sound somewhat timeless? Due to the difficulty to associate music captured on the album with a time-situated popular genre or musical movement.

I don’t think about genres. I like to say that we’re in a post-genre world. I like the fact that it’s hard to map the album genre-wise. To me, that’s an asset! Maybe it’s also a reflection of the way I’ve always ignored the idea of stylistic classification throughout my career. I draw from everything and act with an artistic license to go anywhere in the worlds of sounds and musical forms.

Yes, I think the Touché does help to make ‘Daytime Viewing’ sound somewhat timeless. I’m gratified that others also seem to think so. No other instrument sounds like the Touché, to be sure. I’ve tried to take advantage of its power and uniqueness and the intimate knowledge I have from having co-designed it with Don Buchla.

Jacqueline Humbert was your collaborator in various projects – from the brainwave experiments of the mid-1970s to the art performance group Maple Sugar. And then you released the ‘J. Jasmine: My New Music’ (1977) as a duo and the ‘Daytime Viewing’ was your second recording created in collaboration. Then it seems that for a while you didn’t partner on any new material before the release of ‘Chanteuse’ (2004). Since there’s not much publicly available material regarding the history of your collaboration, I would like to take the chance to ask you about your work with Jacqueline Humbert. How did you meet each other? What inspired your collaborative work? That seems (minus brainwave pieces) to be quite different from the rest of your compositional inventions.

Jacqueline and I met at York University in Toronto. She and several others transferred from the University of Michigan to York when the great experimental filmmaker, visual and performing artist, and member of the Once Group, George Manupelli, left his position at U. of M. and joined the York University faculty. Our artistic collaborations emerged around 1974, first with the brainwave composition Chilean Drought, while Jacqueline was participating in experiments taking place in the Laboratory of Experimental Aesthetic, which I established at York, and following that, during the flowering of the Maple Sugar artist collective in Toronto. Both Jacqueline and I collaborated with many Maple Sugar participants in the creation of new performance and installation pieces. Some of these involved an in-your-face vocal, performance art trio that Jacqueline put together, called the Vi-Breasts, with then Toronto musicians, Diane Roblin and Ellen Band, backed up musically by me on a Fender Rhodes Piano and trumpeter-composer Michael Byron. My stage name was “David Charles” and Michael’s was “Rosy Dawn.” We created various R&B-ish and Motown-ish conceptual covers and improvisations. Eventually, when Jacqueline and I started writing original songs, that led to ‘J. Jasmine: My New Music’, the record originally made for the Ann Arbor Film Festival—which was founded by George Manupelli, by the way—and later re-released on a CD from Big Pink Music, Korea, and finally in a wonderful, remastered vinyl and digital package by Unseen Worlds. Along the way, other collaborations emerged. Jacqueline created projected visual environments for performances of some of my music and other multimedia materials.

Specifically in relation to the ‘Daytime Viewing’: how the idea of the album was developed? It seems that you already had material for it in 1980 but put the recording together in 1983. What influenced the timing?

During 1979-1980, I started working with Donald Buchla on developing the Touché computer-assisted keyboard instrument. We had moved from Toronto to the San Francisco Bay Area, and I also started teaching a little bit at Mills College. I don’t remember exactly when the ‘Daytime Viewing’ concept actually began; but I think it had been germinating for quite a while. I can recall conversations with our very close personal friend, Mary Ashley, another original Once Group artist, about television and fantasy. Upon arriving in the Bay Area Jacqueline spent much of her time developing the narrative concepts, and I started developing musical ideas to integrate with the narrative. Soon, we began to conceive of this as a theater piece, got to work creating multimedia materials, and Jacqueline worked on costumes. We arranged for a performance date back at The Music Gallery in Toronto and kept in touch with various Maple Sugar colleagues, who might be recruited to perform with us. We produced and performed this theater version twice on March 8th and 9th, 1980. We did not yet have the Touché for this version, which was finished and rolled out in a big party in Berkeley on April 14th, 1980. Eventually, I reorchestrated everything using the Touché

The fashion show created by Jacqueline Humbert in conjunction with the recording is quite a thing! How did the idea of it come up? What were the challenges of converging the show and musical performance? Were you also involved in any fashion designs?

The challenges were those of any theatrical musical performance, developing scripts, coordinating with music, producing plots for lighting and projections, making set elements, and all that. A great thing was our association with the Maple Sugar people, who were super generous in helping with everything, devoting time to rehearsing, and eventually performing. The Music Gallery people were very supportive as well.

The Fashion Show was an outgrowth of Jacqueline’s prior work in costume design. Her designs and constructions for Robert Ashley’s Perfect Lives–Private Parts is an example. This also provided a framework for penetratingly ironic texts enfolded in the fantasy aspect of ‘Daytime Viewing’. The recording didn’t use all the Fashion Show texts that were part of the theatrical version. However, they are all provided in the ‘Daytime Viewing’ score. No, I was not involved in any of the Fashion Show designs, just the music. I would not consider myself a fashion designer. I did photograph Jacqueline modeling her costumes.

The Unseen Worlds put out several archival video materials related to the ‘Daytime Viewing’. One of them features early computer graphics. Could you tell a bit more about how it was created and in what way the video was embedded in the show?

Sure. These materials were part of the overall multi-media toolkit for the show. They were projected as set elements and backdrops in various contexts, depending on the venue and the nature of each performance. Bear in mind that the Toronto performances were the only ones with such a large cast. All the others were basically performed by Jacqueline and myself, and these visual materials were deployed uniquely in each situation to augment each individual performance.

These images were created through a kind of digital-analog process. I made programs for a Radio Shack TRS-80 Color Computer that traced out abstract, colored landscapes, pyramids, roads, mountain scape outlines, and the like. Jacqueline made line drawings of figures, costume elements, various objects, and also abstract environments. We positioned those drawings over the screen of a color monitor running the TRS-80 programs. Then we placed a camera so as to focus on the line drawings that were being illuminated by the running computer programs providing diffuse, animated backlighting.

It’s curious to learn more about the history of the performance of the ‘Daytime Viewing’ material. In what venues and in which contexts the music was presented? Are there any stories related to particular performances?

In addition to the two theatrical performances in Toronto that I’ve already discussed, there were several more concert-like presentations in the 1980s. The 80 Langton St. space in San Francisco, a venue that presented lots of innovative performance art and music at that time, and Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland hosted events like that. A more elaborate presentation took place, on an invitation from interactive media artist Peter Beyls, at the truly extraordinary Festival International de Musique Électronique, Video et Computer Art in Brussels, on October 29th, 1981. By this time, we had the Touché, which traveled with us to Europe. I also performed parts of In the Beginning and Future Travel in that show. Another quite unusual setting involved performing on a stage inside the Macy’s San Francisco department store as part of the 1981 New Music America Festival, during which we presented ‘Daytime Viewing’ material in what we called the J. Jasmine Review. It was quite posh, ha.

It’s hard to avoid asking about the instrument. In my perception, the interest in historic Buchla instruments is surging, and materials for the Touché appear here and there. So, I would like to be specific enough to avoid addressing the topics already covered in the media. With respect to the composing and performance practice, how could you describe your approach to creating the ‘Daytime Viewing’ compared to the earlier recording created with Touché – the ‘Future Travel’ (1980)?

Well, of course, these were the first two major works composed with the Touché. ‘Future Travel’ emerged very naturally and is, in some ways, derived directly from my series of eight pieces contained under the umbrella title, ‘In the Beginning,’ each with an individual subtitle. As I began to master the unique power and sonic vocabulary of the Touché, I imagined how I could use it to electronically orchestrate a sonic journey, starting with materials coming from the formal compositional models I developed for ‘In the Beginning,’ and freely expanding them into new worlds of sonic imagery. I was extremely lucky when a friend helped finance a week or so of session time in Francis Ford Coppola’s Zoetrope Studios in San Francisco. I developed ‘Future Travel’ during those sessions, spending each day recording new material, going home at night and composing melodies and harmonies inspired by each day’s work, and returning the following morning to record more material. Eventually, I found the musical narrative that was emerging and refined it into the recording that was eventually released. The wonderful recording engineer, Kathy Morton, was a terrific collaborator in this process. It’s noteworthy that I used both the Touché and the Buchla 300-Series system in these recordings. I had built electronic and software links that allowed these two instruments to talk to each other and use the hardware- software resources embedded in both. Those were very important components of my toolkit for creating ‘Future Travel’.

‘Daytime Viewing’ was composed in an entirely different way. In this case, I worked collaboratively with Jacqueline to set and orchestrate her texts in song forms emerging from the overall concept. I wrote down the score materials that I would need to perform them. Originally, they were made for acoustic and electronic instruments, but not for the Touché. We also recorded backing tracks for some sections, so that I could play on top of them, and we had some electronic percussion tracks I had recorded with an ARP-2500 synthesizer back at York University, which we decided to use. Then, later, I reorchestrated everything for the Touché and some auxiliary sound making items.

Anastasia Chernysheva, a PhD student at University of Illinois.

The interview was arranged by Anastasia Chernysheva, a PhD student at University of Illinois

Headline photo: David Rosenboom | ‘Daytime Viewing’ collage from the Music Gallery (Toronto 1981)

David Rosenboom Official Website / Instagram / YouTube

Unseen Worlds Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube

David Rosenboom interview

Sarah Belle Reid & David Rosenboom – ‘NOWS’ (2022)