Night Sun | Interview | “Got A Bone Of My Own”

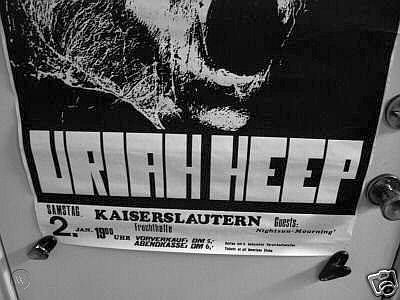

Over the top heavy German group Night Sun from Mannheim, Heidelberg released an album entitled ‘Mournin” in 1972 for Zebra Records. The record might testify as one of the heaviest albums from the 70s.

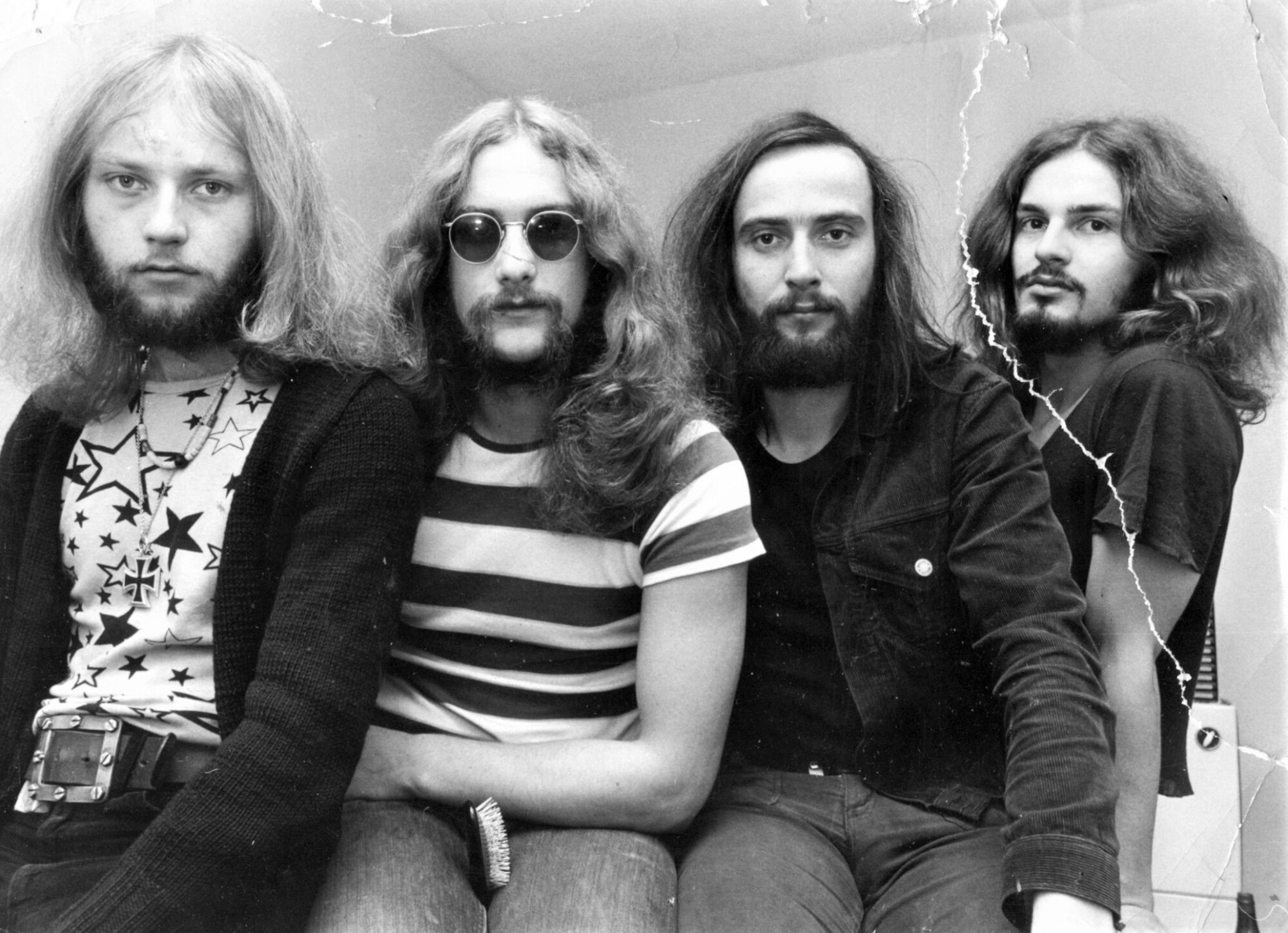

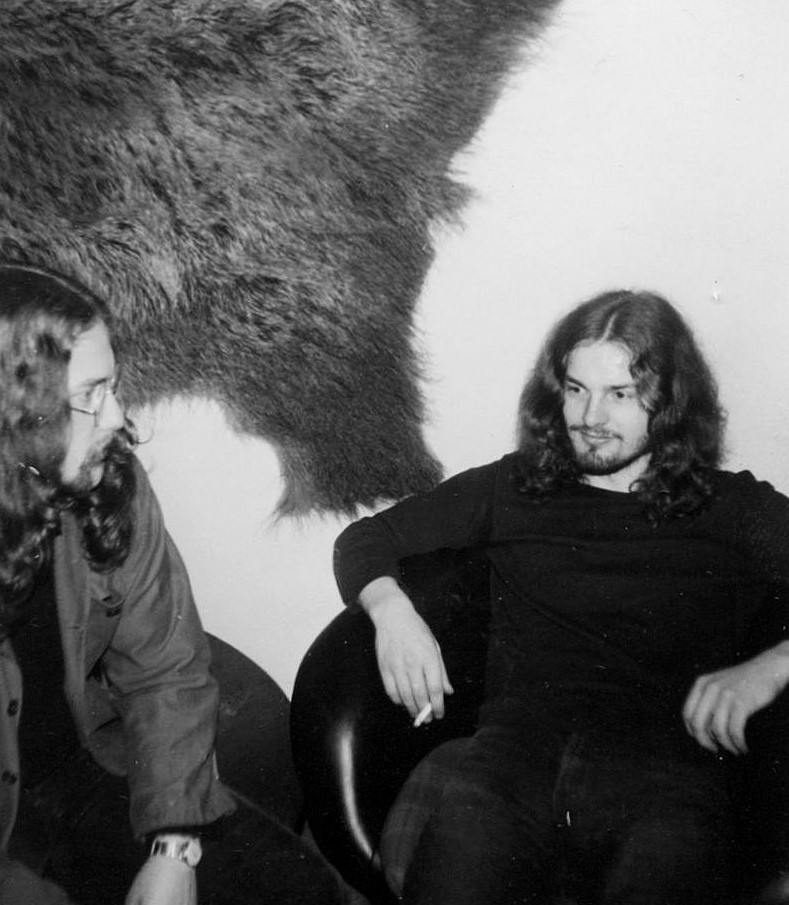

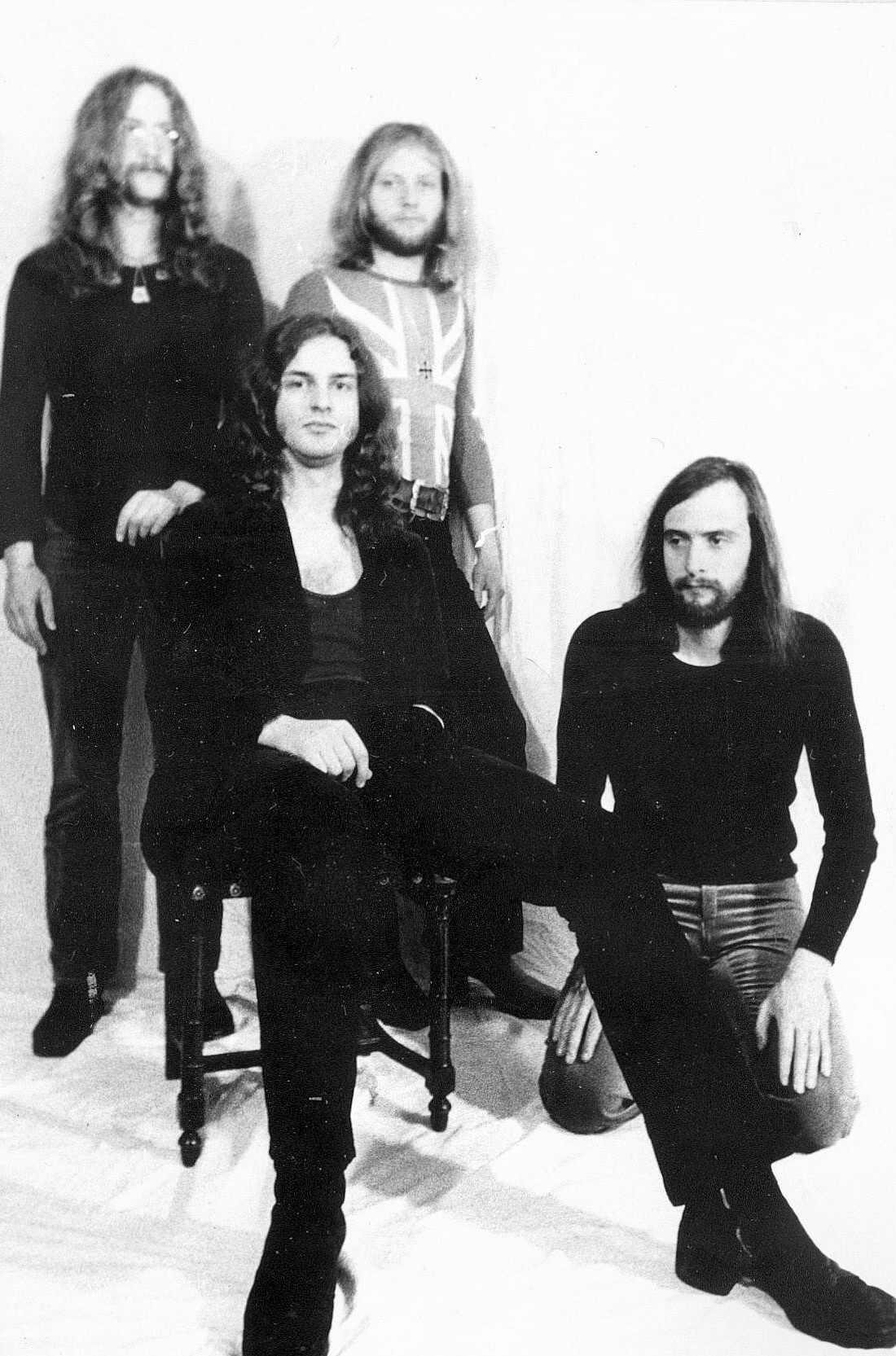

With their sudden shifts of rhythm structures, guitar-with-organ riffing style and some studio effects, particularly phasing, Night Sun had their own unique sound signature. Night Sun’s origins lay in the late-60’s jazz band Take Five who were popular in the Rhine Neckar Area of Germany. Night Sun consisted of Bruno Schaab (vocals, bass), Walter Kirchgassner (guitar), Knut Roessler (organ, piano, trumpet, bassoon) and Ulrich Staudt (drums).

“In every beginning there is magic”

Where did you grow up?

Walter Kirchgässner: I grew up in the city of Mannheim in Germany.

Bruno Schaab: There is a bad word in Germany for a priest. They are likely called “Pfaffe.” The Church was rich, built domes and were a main force in a sunken world. The suburb of Heidelberg where I was born was “Pfaffengrund”. Thank god they had enough land and gave it to poor families and helped them build houses and create a place to be after the monstrous World War II. The land was not for sale, but families could lease it for about 99 German marks per year. In one of these “Pfaffengrund” houses I was born in October, 1950. The eleventh child of my father. Five sisters, five brothers and two aunties, finally together in one place after the storms of war. Father went to school as a teacher of art, mother had more than enough to do, all that cooking and washing (no washing machine) and organizing to keep the household clean. Then my father died in 1956, a big shock for all of us. The burial took place without me and my young brother Al. Winter didn’t want to come to an end. Temperatures were too low that year in the first days of March and we didn’t have enough warm clothes for the youngest children. Our religion was strictly Roman Catholic. Every Sunday we went to church with a choir and kneeling down and standing up again. And sometimes, when the choir and organ gave their best, I got touched inside by the power of music. Also got touched sometimes by mom’s morning ritual when she was washing herself at the tiny sink, she loudly sang hymns. At the end of the session, with clean skin and brushed hair, she used to yell, “Hey boys are you awake?” This part of the ceremony my brother Al and I didn’t like that much. We had to get up and go to school. Doing the homework, being an acolyte, being a boy scout, beeing son, being brother… The best moment was when everything was done and we could hit the streets to meet friends, girls, and had time to spend without being under the family radar. The smell of freedom and adventure; first cigarettes, first kisses, skinned knees and curious minds. Every now and then there was music in the house. The elder siblings played classics with cello, violin, flute, oboe and piano. They seemed to love it. I had a hate and love relationship with it. I missed the flow, the enthusiasm, too much looking at the sheets, too little groove. But beyond that, it was music and I loved the sound of the oboe and the piano. When the show was over I often sat down, jingeling at the keyboard and listening to myself. Mom heard me playing and booked lessons for my brothers Al and me, but the teacher spent more time teaching us phonation instead of going at the piano. I was pissed and quit.

The post-war generation was trying to move as far away from the past as possible.

Walter Kirchgässner: After World War II, young people, especially in Western Europe, were culturally influenced by the Americans who had occupied Western Germany. So they heard rock ‘n‘ roll and rhythm and blues. In the sixties we started to listen to funk music by Wilson Pickett and Otis Redding, but also picked up the sound of The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and The Kinks. A musical revolution took place at the end of the sixties, when musicians like Jimi Hendrix or bands like Cream showed up. In 1969 I saw Hendrix playing live in Frankfurt.

Bruno Schaab: The whole nation was pissed when the communists built the wall, the so-called “anti fascist shelter wall.” I had not too much knowledge about politics, but instinctively I felt that it was wrong to build a fence across half of the country and also felt the fear of war. Although I was convinced to experience the day when the wall came down, and I did. And I still remember the photography of an eastern soldier jumping over rolls of barbed wire into the western sector in Berlin. 1963, John F Kennedy came to Berlin and spoke the magic words “Ich bin ein Berliner.” Berlin roared. Four words gave hope, trust and great enthusiasm. I heard it on the radio. Goosebumps moment. The so called cold war had begun, the iron curtain was reality and political discussions and struggle was like a molesting constant background noise. The beat went on.

Was there a certain moment when you knew this was it and you wanted to play it for the rest of your life?

Walter Kirchgässner: I got my first guitar in 1962 at the age of 10. And yes, this certain moment happened when I heard Jimi Hendrix’ track ‘Purple Haze’. This was like a musical thunderstorm, a deeply felt vibration that completely changed all my musical habits. Some time later, there was another important moment that deeply influenced my own style of guitar playing: this was listening to Ritchie Blackmore.

Bruno Schaab: …And back came sister Johanna from St. Paul, Minnesota. She had spent a year there in some high school and in her luggage she had music. ‘Porgy and Bess,’ ‘West Side Story,’ Peter, Paul and Mary, spiritual records and, my absolute favorite, The Joan Baez Songbook with chords and lyrics. American folk songs. I liked them a lot. That was before rock ‘n’ roll, Elvis Presley and ‘Tutti Frutti’ by Little Richard reached my ears. A neighbourhood guy proudly presented his brandnew Framus guitar, shiny black with a white palm tree and played ‘House Of The Rising Sun’. I was pretty much impressed. He showed me a minor chord and I rushed home, got auntie Anna’s little guitar and started practising. The motivation was clear, soon I could play some chords and started singing every song I knew. Additional motivation was the guy’s hint, that playing guitar and singing will help a lot by stealing girls’ hearts. That was no lie. And the repertoire kept growing when I opened The Joan Baez Songbook. My favourites were ‘Long Black Veil,’ ‘Geordie,’ ‘Portland Town,’ ‘Amazing Grace,’ ‘The Rambling Gambler,’ ‘Stewball’ et cetera. The songs touched my heart. It was so easy to sing them and, by the way, my grades in English class improved definitively. With my own hard earned money, I bought my first guitar, naturally a Framus without palms, but shiny laquery in red and black. Mom gave me a fine upholstered gig bag, I was happy. It was my fourteenth birthday and my voice got darker.

Tell us about some of the very early bands you were part of. What kind of music did you play?

Walter Kirchgässner: I was about 1966 when I started playing in bands. We just covered songs from the charts at that time including some songs from the Jimi Hendrix Experience. My first electric guitar was a Hagström “Viking sunburst,” the amp was Vox AC30.

Bruno Schaab: In about 1966, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Pretty Things, The Animals were our heroes. Rock ‘n’ roll and beat music had wiped out our old campfire songs and schlager. Al and I listened to the first Rolling Stones LP. We played it up and down. What a rhythm, what a voice, what a somewhat dirty way to sing! We were flashed and couldn’t get enough. We rolled over Beethoven, imagined the trip on Route 66 and listened to those new voices that touched us so much inside. That matched my pulse, my heartbeat, it was a new religion. “All you need is love” and nothing else mattered. I became a hippie without knowing what that is. And so Al and I founded a band. We called us The Thinks and it was fun to hear how 98% of our fans struggled hard with the English. We started to play in the church cellar where usually the choir was practising. Later on we played a lot in dance halls. There were a lot of them in Heidelberg and the small towns surrounding. The kids came, paid a small fee for a ticket to dance and the next four hours we were playing all together. Dances were exuberant, wild and sexy, and free and creative. Bands came up like mushrooms after rain. The Heidelberg Starfighters, The Scarecrows, The Passengers, The Phantoms, The Cellar Rats, The Times, The Junior Rockers, The Barons and all of them played covers. I remember a gig with The Thinks I played in the Patton Barracks in an NCO Club. Candlelight dinner with best dressed officers and their wifes. Gee! That hadn’t anything to do with rock’n’ roll. We had just finished a song when a highly decorated officer came loudly yelling at me, “I don’t want you to play that song anymore!” We just had finished playing ‘Back in the U.S.S.R.’ by The Beatles and I was the singer. Cold war time, the enemy was clear and behind the iron curtain. To me it felt ridiculous. That officer didn’t understand anything. In my philosophy the Russians loved their children too, and there’s no reason at all to fear. We can talk over anything, we can work it out, come together and imagine. I didn’t realize that bullets and tanks are strong arguments also, fast, strong and irreversible. In 1968, August, five Warsaw Pact members sent their troops to Prague, Czechoslovakia and roughly interrupted the blooming hopes of freedom and a special socialist way beyond the Russian whip. Brave young men tried to stop the Russian tanks with bare chests, young ladies put flowers into the gun barrels, and tried to convince the bloody young Soviet soldiers that they were completely wrong. People screamed and cried in despair. There was no way to keep freedom. Alexander Dubček was a broken man and resigned. General Jaruselski, with a dark mind and dark glasses took over and the garden of Eden was closed again. June 17th, 1953 the same happened in Berlin. Working men were on the streets. Soviet soldiers and tanks occurred and the dream was over. Prague was a blueprint. And it happened again on June 4th in 1989, Peking, Tiananmen Square. A cry for freedom, brutally suppressed. The fall of the wall let hope grow again, business went extraordinary, huge amounts of money were made on both sides and in China too. Last year the wheels stopped. War in Ukraine and Europe tried too long to dance with the Russian bear. No one dances tango with the Russian bear. In China chairman Mao became a god and the biggest murderer we know. Millions died during the cultural revolution. Young and inexperienced people and high school teachers were ordered to the country only with the Mao bible in hands to live the lives of farmers. Farmers were condemned to cook steel. My hippie philosophy got marks and dents. The American involvement in Vietnam was a disaster. Everywhere in the western world people were in the streets, demonstrating, asking for answers, trying to look through. Hard times for believers. I didn’t know what to believe. Hard to find out what’s the truth and what’s propaganda. Now, in 2023 I must admit the situation is comparable. That day in August 1968 I was dazzled by the awful news from Czechoslovakia, had a flat tire on my bike and was on the way to a classmate, Hanno Giulini. He also played guitar and was a real fan of John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers. We listened most intensively, got an idea of blues and were infected on the spot. Good treachery. Later Hanno founded a band, The Sect, a trio. Their big idols were The Who and guitar player Bernhard Spiegel banged his instrument just like Pete Townshend. Wow! The Thinks had won some beat competition – we won with the song ‘Painter Man’ and ‘My Friend Jack Eats Sugar Lumps’. The price was a piece of paper and a small amount of money, just enough to buy a new microphone, a Shure Super 55. We played nearly every weekend and the kids in Heidelberg knew us. On the radio they played ‘I’m So Glad’. Cream songs were so different. ‘Tales of Brave Ulysses,’ ‘Strange Brew’… Extended guitar solos by Eric Clapton, a virtuous bass and a cutting voice by Jack Bruce and thundering drums played by a ginger haired ghost named Ginger Baker. They gave a new direction, followed by Jimi Hendrix Experience, Deep Purple and Black Sabbath… Blind Faith, Pink Floyd, Grand Funk Railroad, Led Zeppelin. Best of all was that you could watch your heroes on TV, the Beat-Club from Radio Bremen was my favourite show. Much to learn, so much to digest. The times are a-changin, Mr. Zimmerman has prophesied it and Viv Mirus, our most talented guitarist got drafted and had to take the uniform. He hated it. He had to learn to yell “jawohl!” He disliked the smell of the barracks and somehow it felt like a solid depression. The fun was gone.

How did you meet members of Night Sun?

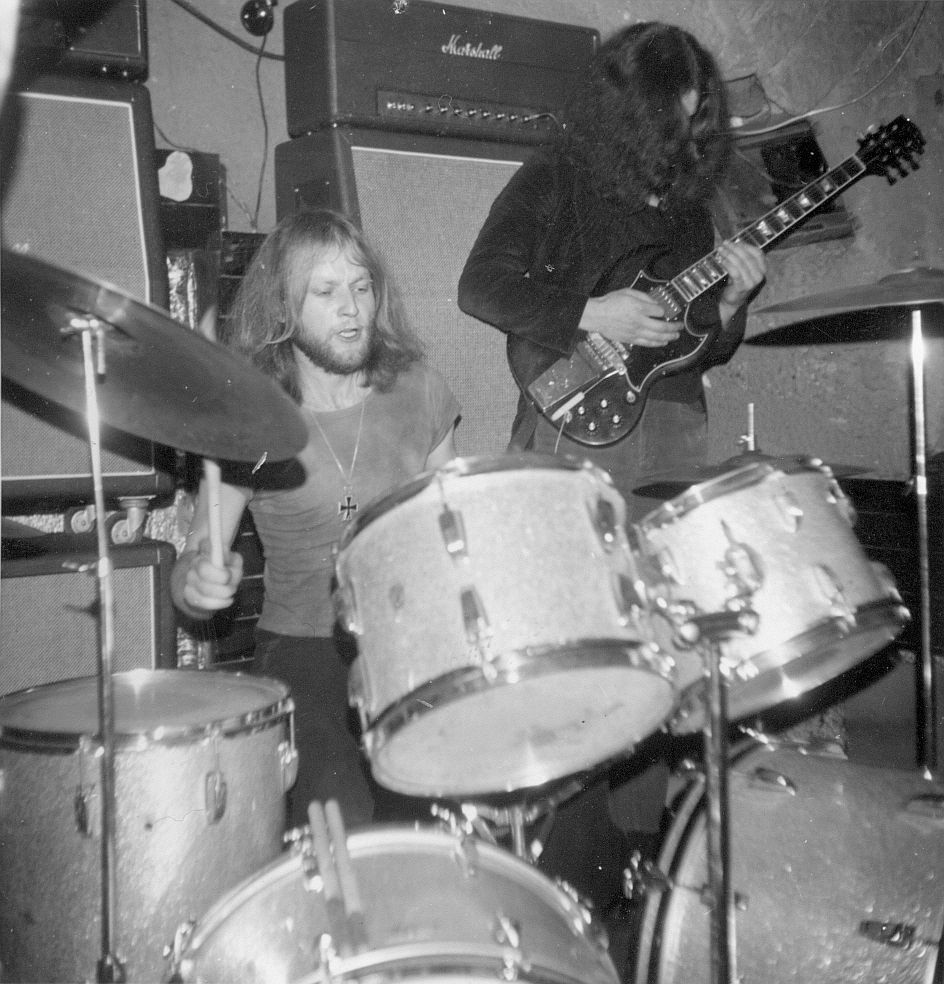

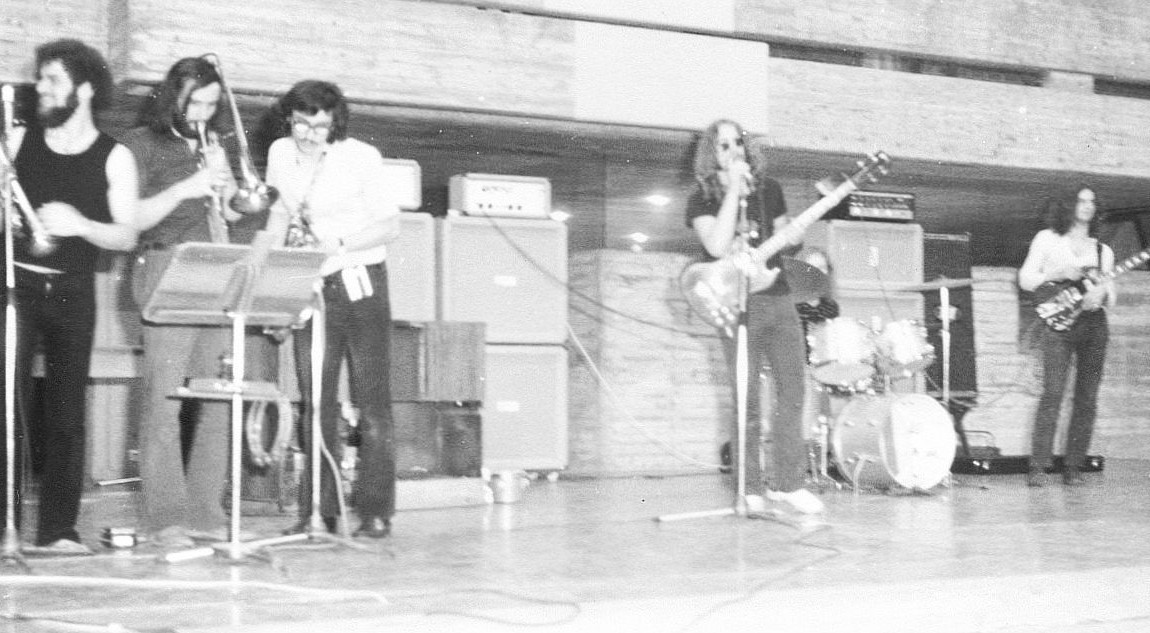

Walter Kirchgässner: In 1970 on a jam session I played Jimi Hendrix’ ‘Purple Haze’ together with Uli Staudt on the drums. At that time each of us had his own band. He thought I was the right guitar player for his guys and took me to their rehearsal. So I stayed with them. At that time this band made music in the style of Blood Sweat & Tears. We also had trumpet and sax players.

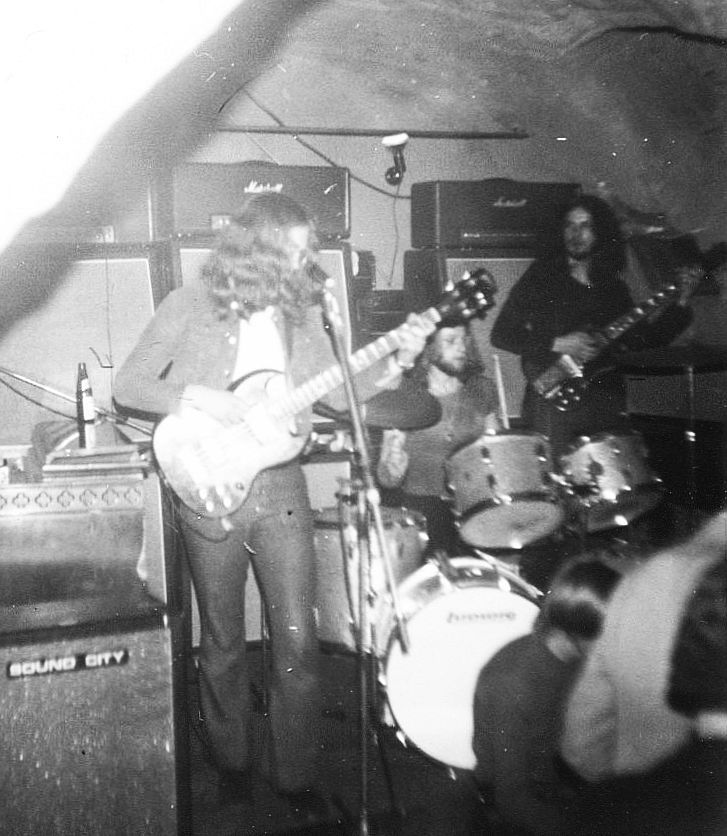

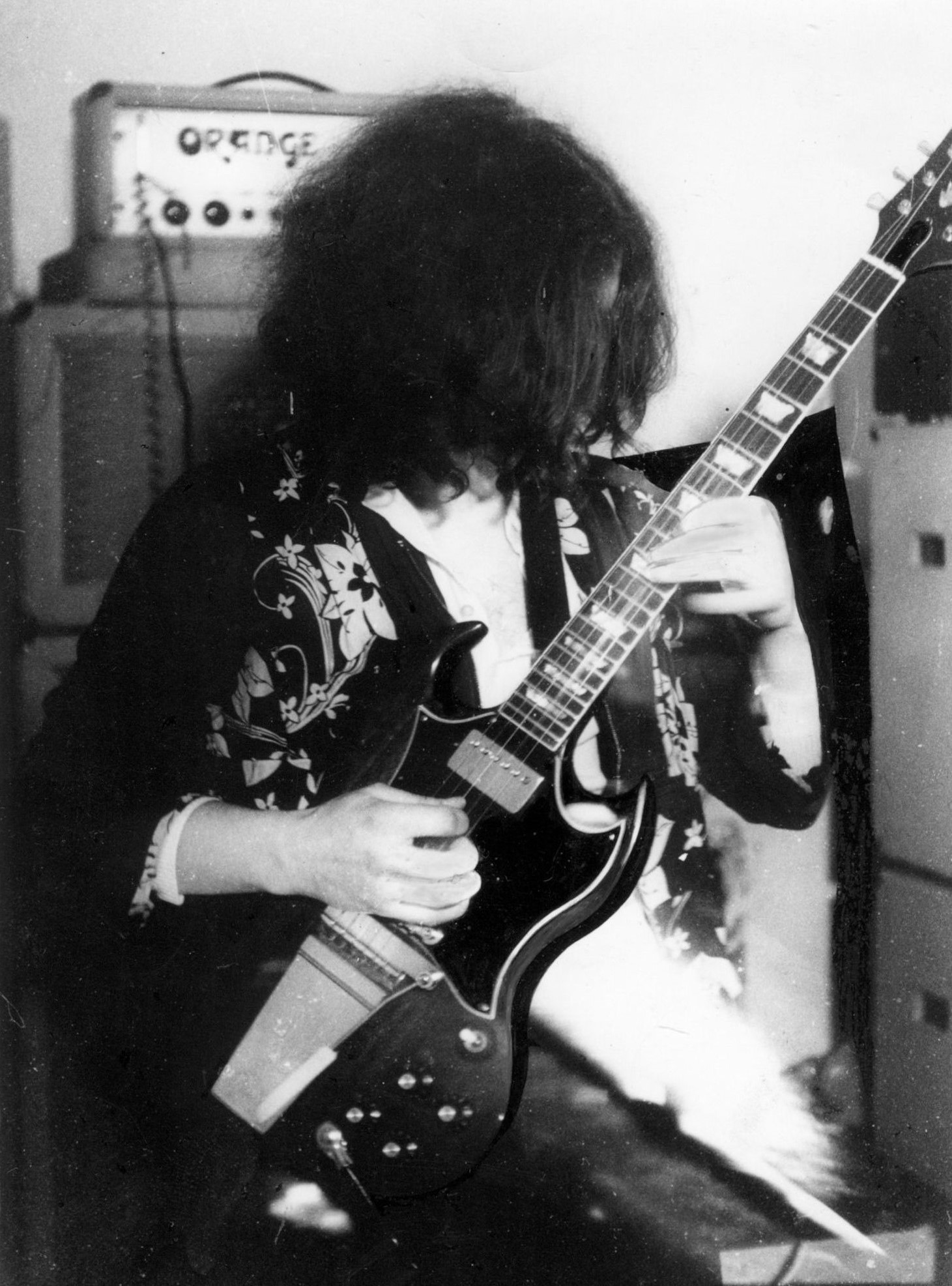

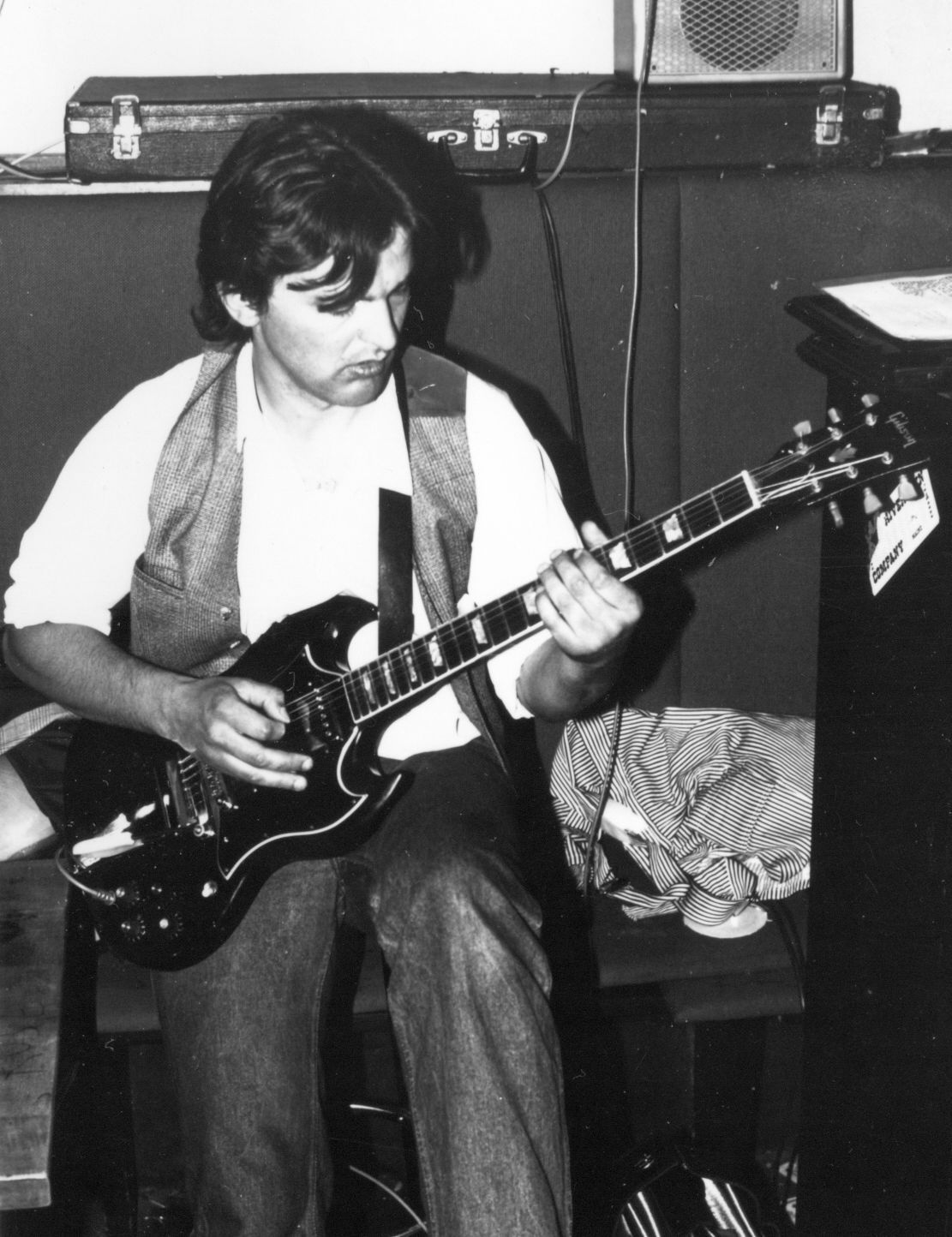

Bruno Schaab: One of our last gigs of The Things happened in 1970 at the campus of Heidelberg University. For the first time I heard Night Sun playing, a band that came from the Mannheim music scene. Drummer Uli Staudt and on the drag rope pistolero on guitar Walter “Jimi” Kirchgässner, a guy from Ludwigshafen, the twin city of Mannheim. Wild and long curly hair and a dark red Gibson SG, slightly arrogant, but a real good player. Pretty fast fingers. Their background was a band named Take Five, a more Chicago and Blood Sweat & Tears oriented band and their different descendents were Kin Ping Meh, Nine Days’ Wonder and Night Sun. I heard them play, extremely loud, self-orientated and self-confident. Knut Roessler played a Hammond organ and saxophone. Breathtaking fast licks between ‘Smoke on the Water’ of Deep Purple and Black Sabbath. I can’t remember the bass player’s name, he was slightly drunk and in search of the groove. Knut Roessler heard me singing and later on he asked me to come to Night Sun. I turned the page. Left my own band behind. Brother Al became an art teacher and additional German Language – yes, yes, yes – Germans learn their language in school. Joke. True. And held on till his retirement without getting a fat liver or depression. He played in a teacher / pupils band named Hitzefrei which means “Heat Free.” Viv Mirus, our talented lead guitarist, stewed in Phillipsburg barracks and learned to defend the country. After that he worked in the finance authorities, got married and didn’t want to play anymore in bands. He died before reaching sixty. God bless him. Erhard Fein, rhythm guitar, went to university, got a teacher too and founded a band and is still playing covers of the music that used to fire our young hearts in the sixties. Axel Eubler, our drummer, went into the printing business, had its own firm and after retiring he showed up again. We tried to get a band together and play Cream-like before, but we failed. No use in beating a dead horse. Axel still kept the beat, played steady and relaxed and still is playing in the old boys scene in Heidelberg, playing nice old evergreens. It is 1970 and Night Sun had a place in the heart of Heidelberg. They lived together in Untere Neckarstraße 64. Situated close to the townhall and not far from the Neckar, a river with greenish-brown waters coming out of the hills of the Odenwald on its way to Mannheim and the Rhein, the mightiest stream in Germany. Tourist buses spit out hundreds of curious Americans, and others from all over the world. Heidelberg castle was their aim and special shops where they could buy souvenirs. In this house, surrounded by an international bunch of tourists, was a free room for me so I moved in.

Please elaborate on the formation of the Night Sun?

Walter Kirchgässner: Night Sun was the result of downsizing its members to three of us: guitar, drums and organ. Bruno Schaab, singer and bass player, came to us a tiny bit later. At the end the band had completely changed its style into heavy rock. The former members of the band who did not match to that transformation had to go.

Bruno [Schaab], what was next for you joining the band?

Bruno Schaab: The idea was to record an album and this would be half the way to big success, a condition sine qua non. And getting started touring all over Europe and – who knows? All we had to do was to get some songs together, what’s the problem? And we had to make some money to buy a PA system and big amps. It had to be Orange amps, cool designed power. “By the way, Bruno, don’t you know, from now on you are not only our singer, we fired your predecessor, you are now our new bassist and by the way again you need an instrument.” Have to admit I was a bit surprised… “And I think you should have a Gibson EB3 bass,” added Walter “Jimi” Kirchgässner. “Jack Bruce plays it and it would perfectly match my SG.” Never before I had thought about playing bass, I used to be a singer and felt good so far. “Ahh, come on man,” they said in unison, “Bass isn’t hard to learn, you’ll make it and it would be more money for us four then.” Strong argument. So we went downstairs to the vaulted cellar and started practicing as soon as I had got my bass guitar. Don’t have the slightest memory where it came from and who paid for it, but it was mahogany red and an EB3. I felt a bit overburdened, but some angels helped me and nobody realized that fact. Knut Rössler came up with an offer to play film music, and payment was excellent. No details. So we packed our instruments and equipment in our big Ford transit, and off we popped trying to find the right address. No navigation in those days. Mannheim has a street system, hard to understand. The old part of the city is segmented in squares and there are no street names, but capital letters and numbers. Meanwhile the bomb holes – leftovers from World War II, I remember them well – were no longer existent and where there once was a hole there was a studio now. Our task had nothing to do with cinema. We had to produce noise for a promotional film that tried to sell atomic power to the people. The title was “The All Electrified Household.” And the scenes where demonstrants were shouting and police were beating were accentuated with “catastrophe music,” as loud and ugly as possible. When the camera showed a blond mother-type woman, ironing her husband’s shirts we had to produce crinkling notes. Shame on us, we did it, felt bad, got the money and bought Orange amps from that. Prostitution, sorry. We were young and weak and needed the money.

What were some of the main influences for you? Did you listen to Radio Luxembourg?

Walter Kirchgässner: As I already mentioned, my main influences were Hendrix and Blackmore. By that time, the sound of Deep Purple was my favourite. I preferred listening to records, not listening to the radio.

Where was the band located? Did they do a lot of shows before you joined the band? What kind of repertoire did they play very early on?

Walter Kirchgässner: The band was located in Heidelberg. We shared a house in Heidelberg which belonged to Knut’s girlfriend. Before I joined them they performed regularly on stage, but did not have too many gigs. They played their own compositions.

Would you like to tell what kind of characters were the other guys from the band and what was the energy when you played together?

Walter Kirchgässner: Bruno Schaab, the singer and bass player, was a really nice guy. Always friendly and very handsome. Uli Staudt on the drums was kind of tricky to describe, and Knut Rössler, who was the oldest of us, was quite smart.

Would you like to tell us what the creation process for the band was like?

Walter Kirchgässner: Songs were created, after one of us had had an idea, for example a guitar riff. And while rehearsing this riff, it was explained to the others who tried to figure out on their instruments something that matched it. The lyrics were always added after the music. Knut Rössler and I were the composing heads of the band.

Bruno Schaab: Working on the songs in the cellar, mostly Knut Rössler came with a phrase, a melody, or Walter Kirchgässner played us a riff, and Uli Staudt and I joined in and we jammed the themes and tried to knit a frame where music could find a place. Often we just jammed in one key, tried to find out what we could do and threw the ideas back and forth. I sang gibberish and whatever came to mind, there were no written notes (I couldn’t have read them anyway and still I am musically illiterate). Tried to find an intuitive theme to each song, it’s a special feeling. Had no words written down and my English was poor. Of course the lyrics had to be in English, the whole world sang English. Who would like to hear German lyrics, this was a no go. At least for the upcoming “stars.” Knut Rössler said, lyrics are not the main thing, just words. Hm. Think, I knew it better.

What was the scene like in the city?

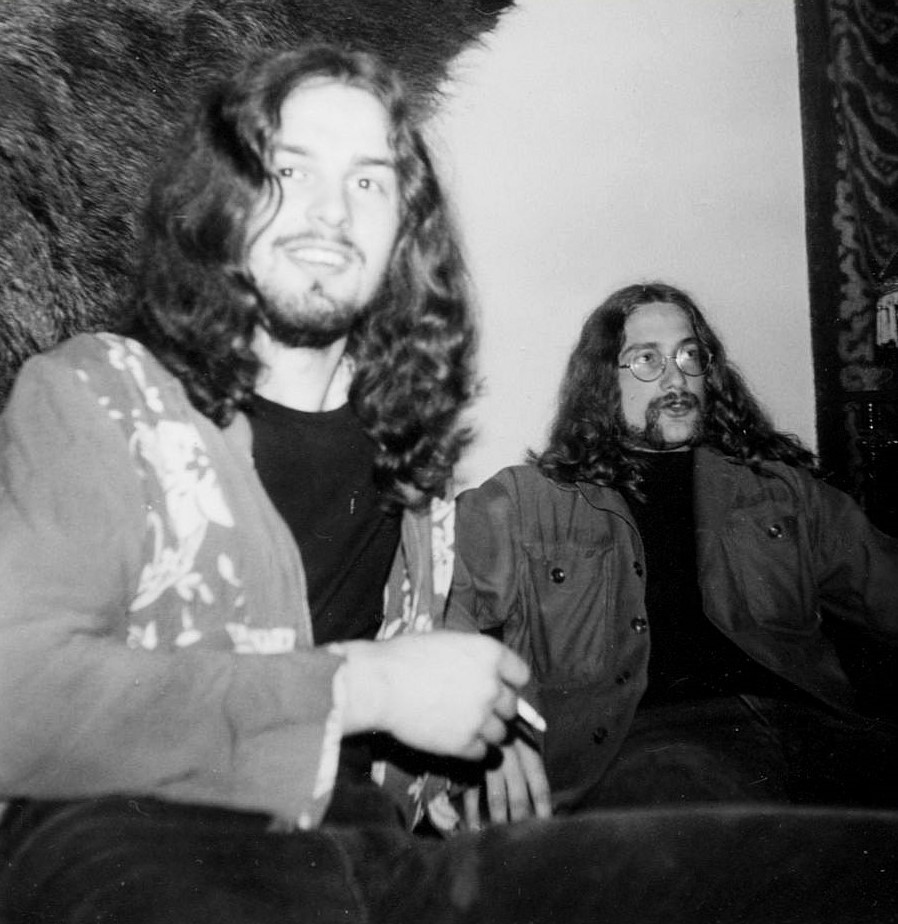

Walter Kirchgässner: In the early seventies the scene in the city of Heidelberg was like a mix of students, hippie and drugs culture – regarding the young people there, of course. Unfortunately I cannot remember all the clubs where we played.

How did you get signed to Zebra / Polydor Records?

Bruno Schaab: Anyway, Uli Staudt and Walter Kirchgässner wanted to drive to Hamburg, to the biggest music scene, with the most music publishers and studios. They drove with a tape of our music onboard. We had recorded some songs roughly and they came back with addresses and hope. Knut Rössler, his family background was a bunch of lawyers, and afterwards fixed a deal with Polydor on their experimental label Zebra. Plus two producers, one of them the young Connie Plank. I guess they had a contract with Polydor. Two weeks in Windrose Studios were guaranteed. To help us save money, Connie Plank invited the whole band into his house, which was formerly the residence of the Russian ambassador. It was big enough for all of us. It was an old villa right on the Binnenalster – a place like a big lake and park in the middle of the city. Big rooms, creaky parquet and three huge bathrooms in blue and white tiles, brass faucets. I loved the place. Just some weeks before that police arrested some drug dealers in the villa next to us and they reported it in the biggest illustrated German magazine Der Stern. Felt good to me, the surroundings were prominent. Otto, the coming shooting star of comedy in Germany also lived in that house. Connie Plank welcomed us with a huge bowl of onion soup and swimming cheese croutons, we sniffed each other like street dogs, picking up the weather.

“Connie Plank asked us to do our setup like we do it onstage”

What was it like working with Connie Plank?

Walter Kirchgässner: Working together with Connie Plank was fun. He had a good sense of humour, but never forgot the professional part. Every day in the studio costs a lot of money. So there was no time to waste.

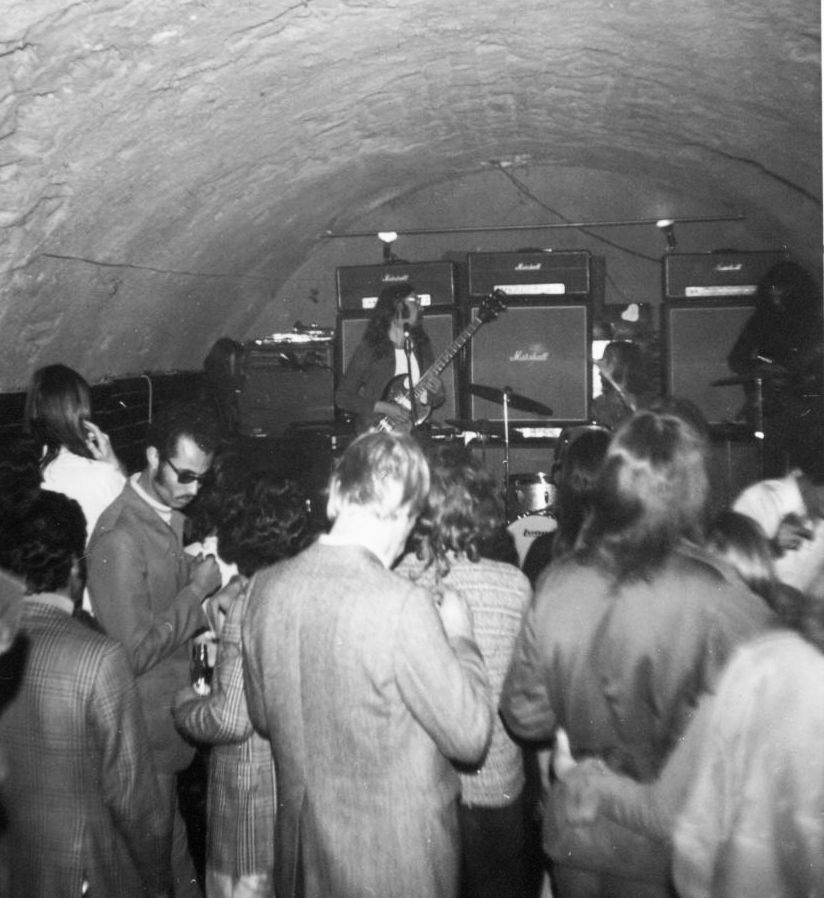

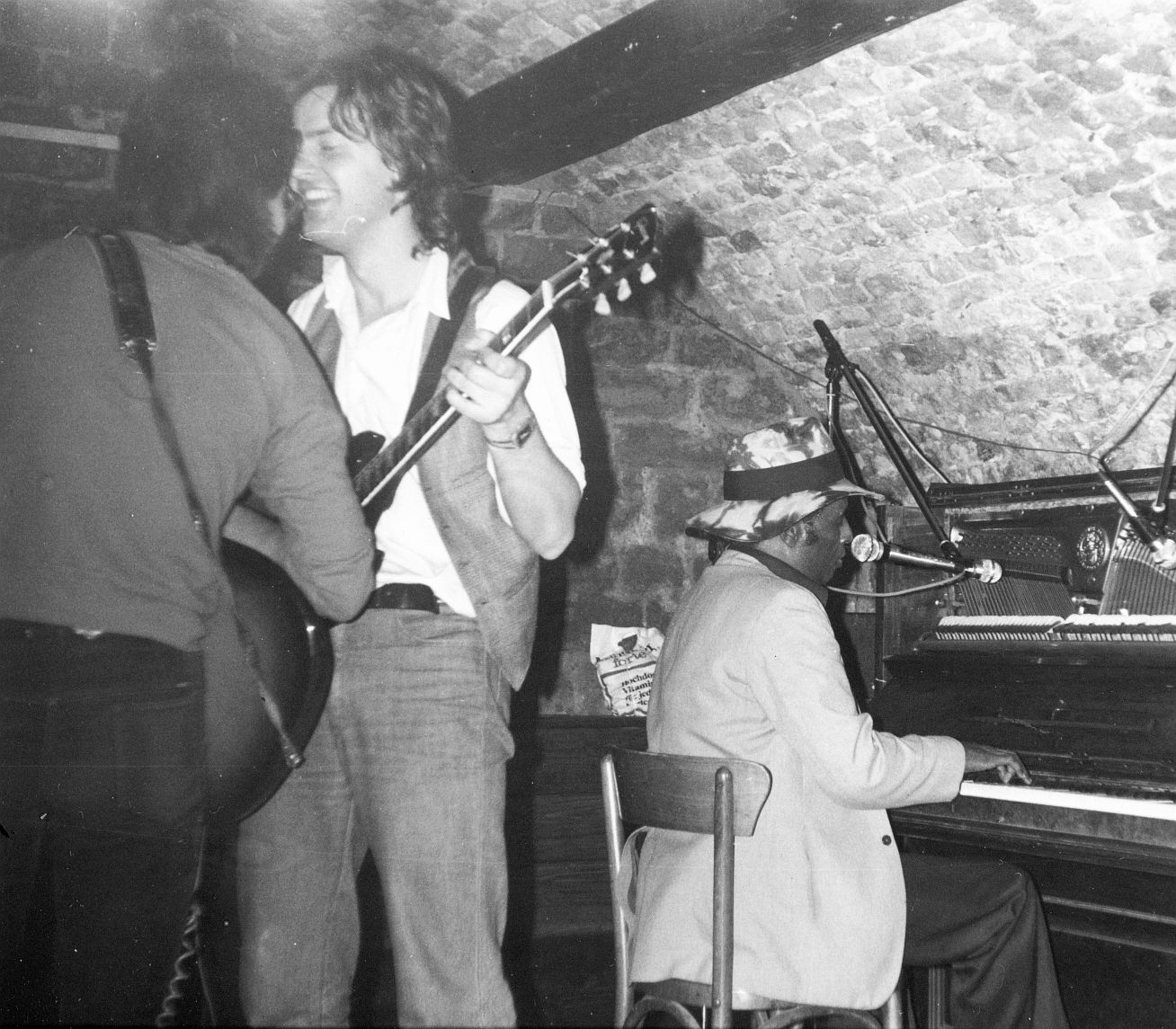

Bruno Schaab: Before we left Heidelberg, Jeff The Dragon showed up in Neckarstrasse 64. A young black guy that Walter “Jimi” Kirchgässner had met downtown in a cellar named Cave 54 during a jam session. The cave was the best address for jazz music in the fifties, a student club and became more and more a beat, R’n’B and rock oriented club. Best hours were after midnight when Heidelberg fell asleep. I hated the spiral stairway to the stage especially when we had to drag down the Hammond organ and the Leslie cabinet. Jeff wanted to come with us to Hamburg. “Sure,” Walter “Jimi” Kirchgässner said, but there was no free seat in the band bus. “Never mind,” said Jeff. “I’ll lay down beside the amps in the back of the bus.” Fucking 700 kilometers of way without heating. It was still wintertime. We organized a sleeping bag and some blankets. It was barely legal and we would be in trouble in case of traffic control, but we didn’t care too much. We fed him with donuts and hot coffee and started the engine. When we reached Hamburg, we dropped him off near the Reeperbahn, Hamburg’s center of sins. He was in a good mood and off he went. What I didn’t know was that Jimi gave him the address of Windrose Studios. Thank God he did. At noon the next day we got our gear downstairs into the right hand studio, (the studio to the left was occupied by Les Humphrey and the Les Humphries Singers), a big room with lots of microphone stands and smaller separees for drums and I don’t know. Connie Plank asked us to do our setup like we do it onstage. He wanted to record the band as whole whenever possible. For sound reasons Walter “Jimi” Kirchgässner played cracking loudly. Connie Plank frowned, went and came back with some old mattresses. He placed them carefully inside a separee box and the problem was solved. He asked Uli to play drums, closed his eyes and became a big ear, listening concentrated. Afterwards, he knew exactly where to put the microphones. He came to me, kneeled down, asked me to play the bass and crawled around the speakers to find the best place to put the Sennheiser. He swore it was the best microphone to pick up bass. And we started the recording session. We worked twelve hours every day, sometimes more. Junk food, lots of cigarettes – Connie Plank was smoking like a steam machine – barely no alcohol, just tea and coffee. Sometimes a beer in the early morning hours was ok. It was good to work with him, he was patient, encouraging and if we had played weak parts or made solos too long he said “don’t worry, I’ll cut it out.” He was a master of cutting, tricky and experienced. One time only he nearly lost his serenity. We worked on a passage with a break and Walter “Jimi” Kirchgässner was to fill in with an always fitting guitar line. We had played the song live several times and never had a problem continuing on the point together. This time there was no togetherness. The guitar line was half a bar too short. Connie freaked out a little. I remember words like “kindergarten,” “time waste” and “Hasenficker Gitarre”. I won’t translate that.

What kind of instruments, effects, pedals and gear did you have in the band? You must have been extremely loud?

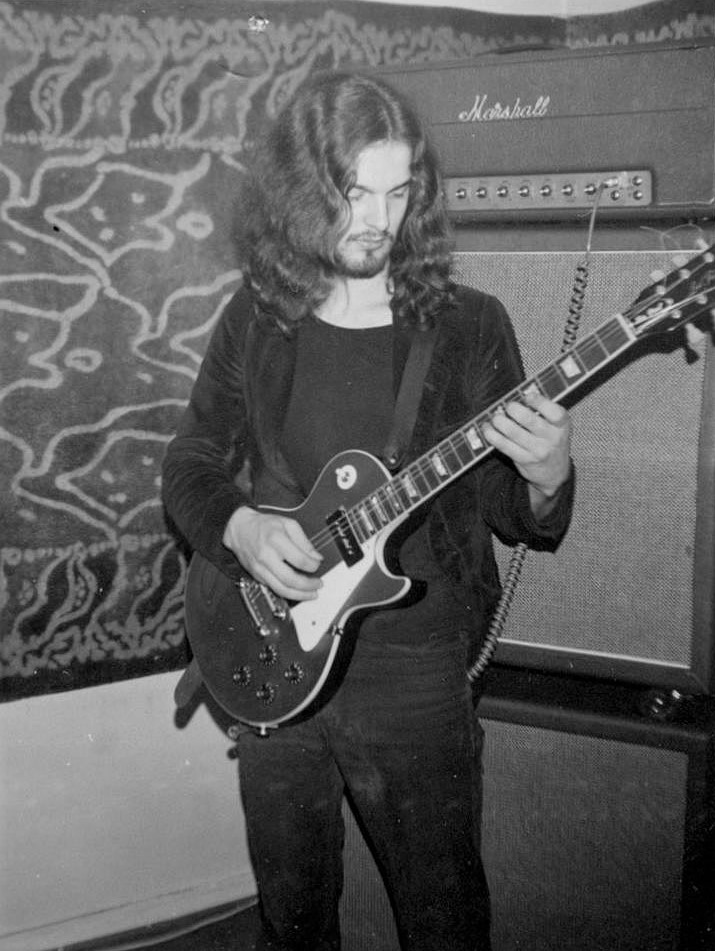

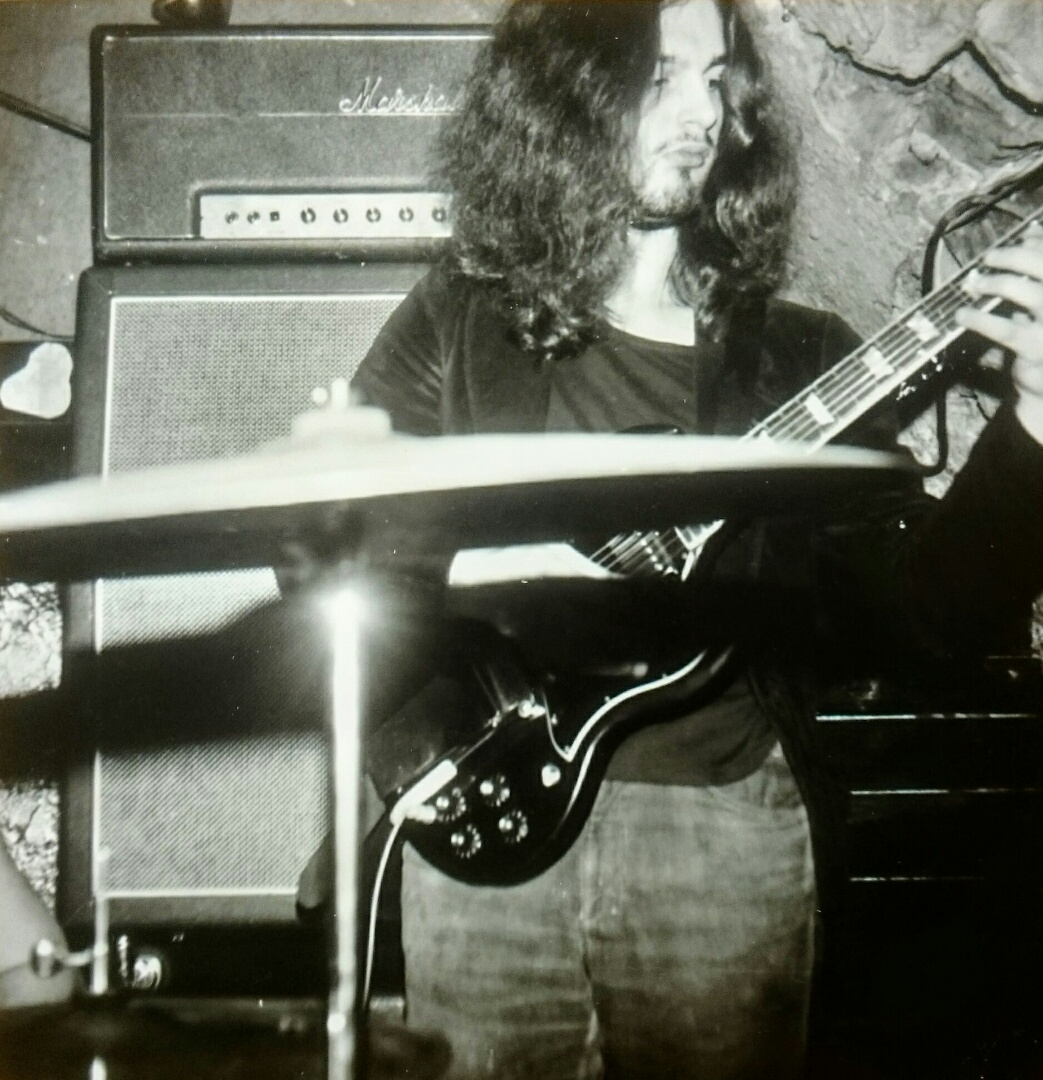

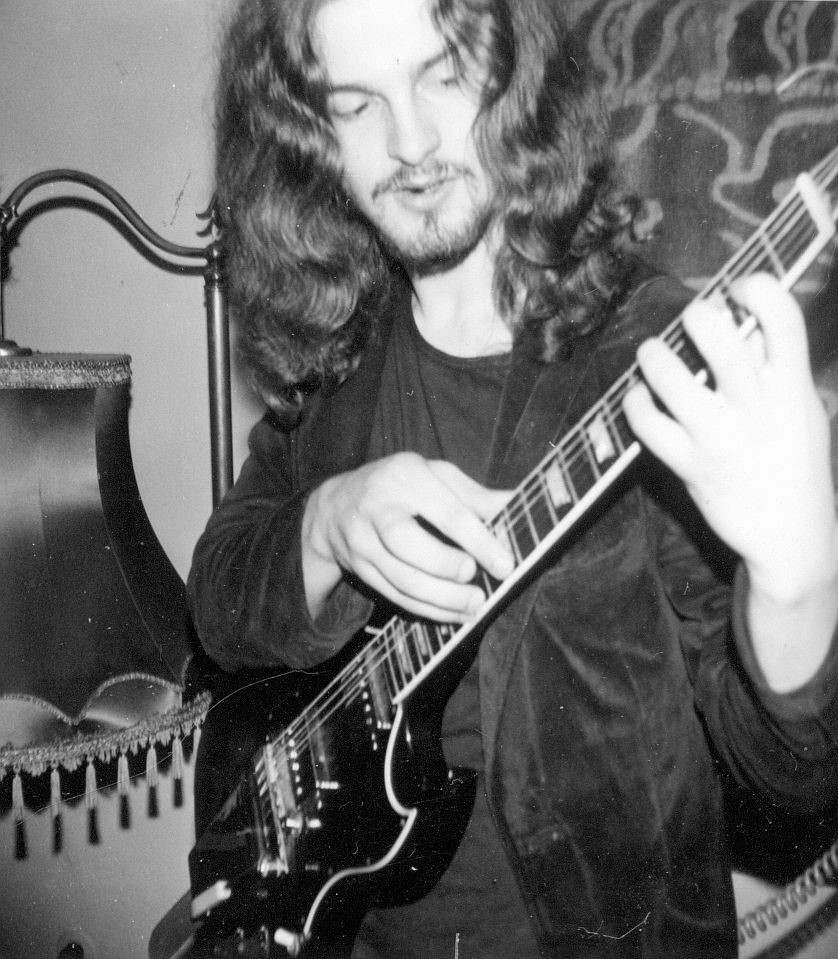

Walter Kirchgässner: Yes, we were rather loud. I played a 1964 Gibson SG and a 1972 Fender Stratocaster. As amps I always preferred Marshall and Vox AC30. In my early days I also used a Vox wah wah pedal. The Gibson was a Christmas present from my father, Karl-Robert Kirchgessner who spent his whole Christmas bonus to buy me that guitar. I still have the precious guitar with me.

Please share some of the strongest recollections from recording ‘Mournin”?

Walter Kirchgässner: Unfortunately, this is a somewhat unpleasant memory. Because our band had serious problems playing together on the first day in the studio. During the recording of ‘Nightmare’ we got faster and faster. It would have been better if we had started the studio work with a lighter tempo piece.

Bruno Schaab: Strange people sometimes came in, nobody knew them. I remember a longhaired thin guy. He sat behind the studio screen. He seemed unremarkable, and listened silently. When we took a break and went to the “Kommandozentrale,” the room with the recording desk and the big 24-track tape deck to re-listen to the last recording, the guy said, “your bassist is lousy. Kick him out and let me do it. I will do it better, for sure.” Knut answered spontaneously, “I think you better leave quickly before we kick you.” More and more I was thinking about the non-existing lyrics. To make up my mind I gasped into the other studio, opposite of ours and found Les Humphries doing recordings with one of his singers. I felt a little sorry for her. She had to sing a verse with not too many words and Les was never satisfied, so she sang again and again and he criticized this or that. They worked with full concentration for an hour, the same verse again and again. At the end they changed the method. She sang wordwise the verse and I left before the recording came to an end. Strange way to sing. When I returned to the “Zentrale,” Jeff The Dragon was sitting there and belched “hey man, dig it?” While the others were doing overdubs and saxophone parts I talked to Jeff about my dilemma, we talked about my ideas and my poor English. “Be cool man, I’m in the mood, I’ll help you. Just make my mind move.” And out of his parka he took two pills, pulverized and sniffed the powder and started writing.

How come did you name the band Night Sun?

Walter Kirchgässner: We had some discussions and finally agreed to one of our proposals.

Whose idea was the cover artwork? What was the concept behind it?

Walter Kirchgässner: I think this was Connie Plank’s idea. If there was all in all a certain concept behind it, this is what I am still asking myself.

Bruno Schaab: We didn’t have anything to do with the cover design, that was up to Zebra

Would you share your insight on the albums’ tracks?

‘Plastic Shotgun’

Walter Kirchgässner: The main guitar riff is wild and hectic. The music somehow overturns itself. I like Knut Rössler’s piano solo.

Bruno Schaab: Inspired by an LSD trip somewhere downtown.

‘Crazy Woman’

Walter Kirchgässner: Actually I like this piece. Connie Plank’s influence as a sound engineer, also on the guitar solo, cannot be ignored. I would have liked the sound to be drier and less technically distorted.

Bruno Schaab: Crazy boy welcomes crazy girl.

‘Got A Bone Of My Own’

Walter Kirchgässner: A real heavy guitar riff from the very beginning, completed by homogeneous and compact complemented by the whole band. Unfortunately, the drums drag at times.

Bruno Schaab: Leave me, I’m on my own, got my own religion, got a bone of my own.

‘Slush Pan Man’

Walter Kirchgässner: Again a sophisticated guitar in the center, a riff with diminished chords. The whole band sounds like a heavy steam engine.

Bruno Schaab: Drugs, needles and temptation.

‘Living With The Dying’

Walter Kirchgässner: At the song’s end, nice dialogue between organ and guitar, drum solo in my ears, some sort of a too long drink.

Bruno Schaab: Everyone has got to deal with his own demons and got to face the end.

‘Come Down’

Walter Kirchgässner: One of my favourite lyrical songs, music by Knut Rössler. Bruno Schaab sings so nicely! I like the melodic guitar solo at the end.

Bruno Schaab: Sometimes life is joy if you can find it within yourself. Talked about people who came to the studio out of nowhere. Coincidence is a non kosher word. A beautiful hippy woman came in when we did the voice recordings. Yet, I had no concept for the ballad. During a break she showed me her scrabble book and I found some inspiring lines. I didn’t even know her name. Thanks lady, thanks a lot. The words fit perfectly.

‘Blind’

Walter Kirchgässner: Pure rock ‘n’ roll. And again diminished harmonies.

Bruno Schaab: Longing for harmony and peace, longing for a key to understand.

‘Nightmare’

Walter Kirchgässner: Actually a piece which is suitable for the very first spot of the album. But regarding its tempo, as I mentioned before, it was hard to get the band sticking musically together. So the first day in the studio it was really some kind of nightmare.

Bruno Schaab: Sometimes life is a nightmare, sometimes you’re full of fear.

‘Don’t Start Flying’

Walter Kirchgässner: Quite a jazzy number! Nice dialogue between guitar and Knut Rössler’s saxophon.

Bruno Schaab: Social comment, the feeling of being like a puppet on a string, feeling hypnotized and manipulated.

Did you do any bigger gigs when the album was out?

Walter Kirchgässner: No, just clubs.

How pleased was the band with the sound of the album? What, if anything, would you like to have been different from the finished product?

Walter Kirchgässner: All in all, we were quite pleased. In my opinion, sometimes there are too many technical effects by sound engineering.

Did you ever experiment with any psychedelics et cetera as a band?

Walter Kirchgässner: Sometimes we smoked cannabis, but not really much.

How did the band come to an end?

Walter Kirchgässner: In Autumn 1972 I left the band and went to England. This was the end.

Bruno Schaab: During my time with Night Sun, I had to work in social service in a cancer hospital for 18 month because I refused to go to the army. Problem was, I couldn’t get enough days off to go to Hamburg and work on the recordings. So I didn’t tell anybody anything, not even my mother and drove to Hamburg without permission. What could they do to hinder me? Nothing. When I was back and showed up again there was a note for me. “Immediately see your boss!” Knocked on his door, he barked “come in” and as soon he saw me he jumped from his chair and started shouting harsh words. Then he came to an end, sat down and asked me with a grin to tell all about the recording session. I asked what would be the price to get away with it? He said a copy of the LP with autograph plus a solid bottle of whiskey. He was an ex-mayor, but a fine man. As soon as we had the album in hand I handed it to him. While Walter was in London, Knut was on vacation with his girlfriend Amelie when he got the terrible news. His father had lost his life in a traffic accident. Knut buried his father and made a decision. Within three and a half months he made his final examination and cancelled Night Sun. No one of the rest of the gang had the will to take leadership. That was it.

Walter [Kirchgässner], how long have you stayed in the UK?

Walter Kirchgässner: Stayed there just a couple of months…

What followed for you later on?

Walter Kirchgässner: After having returned to Germany I got my high school diploma and in 1976 started studying philosophy at the university of Mainz.

Were you part of any other bands later on?

Walter Kirchgässner: Yes, for a little while I was part of some blues band, also played guitar in a band called Nine Days’ Wonder.

I know you got involved with cello in string quartets and classical orchestras.

Walter Kirchgässner: In 1981 I started playing the cello. After having done a real lot of practising I was ready to join a classical orchestra. This is what I am doing until today.

Walter [Kirchgässner], at university you studied philosophy, would you like to tell us more what in particular interested you the most?

Walter Kirchgässner: I especially read the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant.

Bruno [Schaab], tell us about your time with Guru Guru?

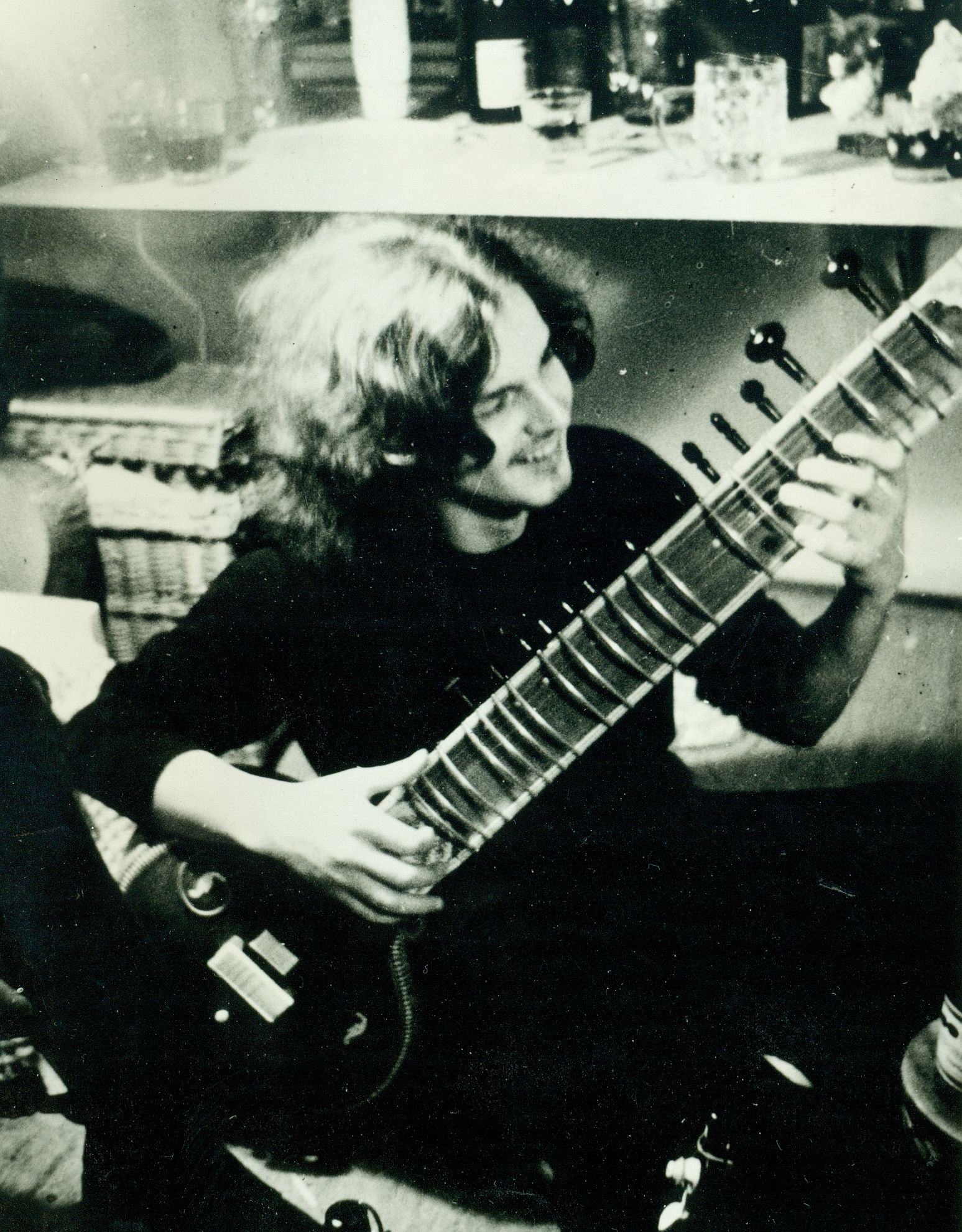

Bruno Schaab: We are in the year 1969, spring, hippie times. Colours, psychedelic trips, mushrooms, pot, macrobiotic food. Further up the The Beatles got in touch with Maharishi Yogi, Gurus and transcendental meditation got hip. The wave swept from India over England to America and, as usual with a slight delay, finally to Germany. It fits well with the “make love not war” generation and the experimental mood among youngsters. Parents, teachers and straight people shook their heads and hoped that this fog in the brain wouldn’t stay too long. But it was tough and not so easy to overcome. Mani Neumeier, the drummer and founder of Guru Guru, didn’t want to surf on the Krishna board, but he was always looking for inspiration with a wide open mind. His time with The Irene Schweizer Trio (Switzerland) had just ended and he was looking for a name for his new project. On a rooftop he watched a couple of pigeons at their wedding gooeing and dancing – that was it. The name Guru Guru was born. Bass player Uli Trepte and Mani met with Ax Genrich. He was a former member of Tangerine Dream (Edgar Froese) from Berlin. He was a very curious experimenting guitarist in search of new sounds. Became the third member in the new formed trio. Guru Guru started. They recorded three LPs, ‘UFO’ in 1970, ‘Hinten’ 1971 and ‘Kanguru’ in 1972. Guru Guru used to start their set in complete darkness, all spots and stage lights skipped. The only thing the audience was able to see were two red control lamps on the Hiwatt amps, demon eyes. Three dark shadows went on stage and sat down in the middle. They lightened up a chillum and smoked silently. Everybody could smell it, everyone knew it, it was highly illegal, a subversive headline. The audience was positively surprised, murmured and giggled most excitedly. Mani counted down. With smokey minds the three shadows stood up, took their instruments, went to the standby waiting amps, set on full power. When Mani shouted “CERO,” Ax and Uli skipped the standby. Hell broke out. Looking back, stroboscope lights and a howling feedback was a real torture to men and material. Out of this chaos came Mani’s cool drumbeat, spots spot lights and Ax’s guitar was followed by the magic monotone basslines from Uli Trepte. Wow, what a beginning. The idea behind it was: everything is allowed, but not if it’s normal or conventional. It had to be flippy, twisting, unusual. The music intended to draw bows, float, with calm and relaxing parts, pianissimos and crescendos, mainly free improvised parts with few anchor points and bizarre maneuvers. High risk. After a while, they gave up the holy smoke ceremony – maybe sometimes even revolution gets boring – and Mani got in touch with the audience with “Hallo Leute” which then sounded pretty cool. At least it was better than “Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren.” In every beginning there is magic. As soon the noises had changed into the intro of a song, Uli Trepte started with a speech. He started low and he spoke gibberish, a fantasy language. No understandable meaning, but an increasing power and dramatic emphasis sounded more and more like Hitler himself. He ended up with the words “Immer lustig,” spoken with a clearly eastern or russian accent, people were dazzled and the music took over. During a concert in Deggendorf, Bavaria, some guys in the audience felt provoked and started a pretty violent fight and approached the stage yelling and threatening at the musicians. The band had to leave the stage and got away with beating hearts. Uli’s left little finger was broken and he couldn’t play bass for some weeks. This fight broke their friendship with Uli, but I think the breaking up was happening already a while before this event. Ax and Mani didn’t want to continue with Uli and asked him to leave. To keep the wheels rolling they urgently needed a new bass guitarist. It’s 1972, spring, the hippies were still alive. Students were demonstrating against the Vietnam war in the streets, chanting “Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh” and waving with the red little book called the Mao Bible. The sound had changed. Some of the student leaders got radical and declared war on the system and they meant what they said. They vanished to the underground, calling themselves the Red Army Faction. robbed banks and stole money. Their faces were known everywhere in Germany, everywhere one could see the “WANTED” posters. They got weapons and learned to shoot and bomb and terrorised and threatened political and economical vips. Mani was still looking for a bass player. He had good connections to the Munich music scene – not the Giorgio Moroder thing, disco – no way! He knew bands like Amon Düül II, he knew Roman Bunka from Embryo. He asked Roman to meet Guru Guru and have a session at the Guru Guru’s place in Langental, east of Heidelberg, up the river. Unfortunately, there was no bass amp anymore in the beautiful rehearsal room with the big windows, the free view to the valley and the swing door with mirror tiles. Therefore, Mani visited in the heart of Heidelberg the place of my band Night Sun, which had just split after having finished recording their first LP, engineered by Conny Plank. Heidelberg, written like this, wasn’t only a student city with an increasing dope scene around the world famous Holy Ghost Church, but also the band name of Ax Genrich’s first own band after leaving Guru Guru. No idea how he found us. We have never met before. Maybe he got the address from a local music shop or just found a free parking space near the house where I lived, right in the ancient part of the city, close to the Neckar river and not far away from Heidelberg castle. Mani asked me to lend him my bass amp and also invited me to join the session. I was glad to do so. We picked up Roman Bunka at the main station and headed east, up the river. When we entered the Krone, a former restaurant where the Gurus lived, the first thing I saw was Mani’s drumset with a big fat gong and a gayly sprayed compound of different drums he called the zonk machine. They jammed with Roman for about two hours and I found him playing pretty solidly and well fitting. I would have hired him. No doubt about that. They took a break and wanted to have coffee in the Linde, a restaurant 50 meters down mainstreet where you could get the very best cheesecake. (Later on, getting coffee and cheesecake there became kind of a ritual when we worked on our songs).

Well, I thought the guys will have something to talk about so I let them go alone. I took up the bass and played some stuff I liked, licks, riffs, grooves. Nothing special, maybe the bassline from ‘Hey Joe’. I liked the acoustics in the Krone room. All of a sudden Mani sat at his drumset and was grooving with me. He’s a fantastic drummer and he can play witty stories from all over the world of fantasy. Ax joined in with his black Les Paul and seasoned our brew with overloaded echoes, feedbacks and bizarre clusters. I don’t know how much time we spent in our musical conversation but it didn’t matter. After this, instead of Roman Bunka, they asked me to stay and join. So I moved into the two rooms behind the swing door with mirror tiles with my girlfriend Inge and a young dog called Knödel. In Langental everyone of us had daily routines. Besides rehearsing and getting our music together, Ax was disassembling and screwing his guitars. Mani checked the office and fed the tiny ants that lived in his table with breadcrumbs and sugar – the table was a rootstock he found in the forest – and I took long walks outside, my Fender Jazz Bass hanging on my shoulder and Knödel following with her nose on the ground. Interrupted by playing concerts we constantly worked on the new songs we wanted to record soon. My favourite was “The Story of Life” and “Women Drum.” ‘Der Elektrolurch’ was born, a bizarre tune with an interview part. Mani is still playing ‘Der Elektrolurch’ these days, I swear. I had the sentence: “ebbes bessares als de Dohd weer ma allemol finne.” Nobody ever understood that. It’s the roughest Heidelberg dialect and is a quote from Grimms Märchen, the fairy tale of the Bremer Stadtmusikanten. Translated it means: We’ll find something better than death anyway. The fairy tale is about some worn out guys and their plan to go out on the streets, play music, and make their living. My time as a member of Guru Guru was crazy and completely different from what I was used to. It was magical for me to play progressive rock music, not only in clubs and pubs roundabout Heidelberg und Mannheim, but all over Germany. One of my first gigs was in Bischofshofen, Switzerland. We met The Crazy World of Arthur Brown. Everybody knew their hit ‘Fire’. We played at festivals, drove up and down the autobahn and crisscrossed the country. We came to Hamburg for a concert at the campus, met a wild bunch of keen hippies that had just founded Release Organisation, a center to help young heroin addicts to get clean. They started a hostel where kids could find a place to be at low cost. The food was freshly cooked in the most hip macrobiotic style, vegan long before the word conquered the world. We met one of the leaders of the Release Organisation and got friends with Mick Kessler, a real Hamburg street fighter, fearless and most eloquent. He collected a lot of money by presenting the idea of Release to managers and entrepreneurs. No PowerPoint presentation, but just a young guy with long hair, cowboy boots, and an unbreakable self confidence. Six years later we met again and he asked me to join Desperado, one of the few punk rock bands in Germany with German lyrics he had just founded. While thousands of students in the US and the western world were demonstrating against the war in Vietnam, while dozens of Buddhist monks burned themselves, the authorities and police tried to stop and beat down protest demonstrations, trying to suppress the new wind of change. Guru Guru kept on rocking – what else can poor young men do? Throw Molotov cocktails? Join the RAF? One of my most memorable gigs or better: ways to a gig was in Berlin, where Ax was born.

What a city, what a spirit. The large concrete wall separated west from east, bad from good, depending on one’s point of view. After World War II the capital city of Germany was a pile of rubble. Anyway, war was over, thank god. Amerika brought democratic structures, chewing gum, chocolate, Lucky Strikes and sour mash whiskey. They also shared their wonderful music. We got in touch with jazz, blues and upcoming rock ‘n’ roll. We listened to the radio, heard songs and voices that came straight out of the heart. We changed the way of dancing. “Let’s twist again.” Music became more popular than ever. That changed lives. The sweet smell of freedom made living smoother and easier. Otherwise Germans still would dance polka, not far from march music. From Langental to Berlin it was a long ride, about 650 km. For the first time I had to cross the border between west and east Germany. I was excited. Borders. I hate them. Everywhere. The worst of all borders was the one that divided our country. Ritualized bullshit, most ridiculous, boot banging soldiers, barbed wire everywhere, floodlight spots and shabby shacks for controlling anything and everybody. Kalashnikovs, tanks. The manners were rough, unfriendly and menacing. First of all an officer came to the long line of cars and asked every driver loudly, clearly and most seriously if we had any weapons or ammunition on board. Sure we had. We all had a turnpiece in the pocket. Thank God they were more interested in gunpowder. Absolutely humourless. The Devil knows why they asked us what we want to do in Berlin. Play music, we said, rock music of course. They told us to open the backdoor of our absolutely freaky sprayed touring bus. They asked stupid things about our loaded gear. We weren’t respectless, but maybe we weren’t too impressed and had too long hair. Just to tease us they harshly ordered us to unload. Half an hour later they got bored, went away. We packed again. Not too pleased. They winked us away, but we couldn’t leave. Mani was missing. He was out of sight and nobody knew anything. We waited some painful fifteen minutes, nothing happened, and we slowly got a little embarrassed. The shabby shack door opened, an officer came to see what the fuss was about. At the last possible moment before the uniformed brother reached the bus, Mani came out of nowhere, jumped into the car, said “hurry up, hurry up” and rolled down the window. He barked at the officer, something about toilets and emergency, and we rolled again. Uff, so good to roll. We got away gladly, no one tried to stop us and we could continue the trip. Mani told us the hair-raising story of what happened to him while border police checked our tour van. He went looking for the washroom behind the control shacks, found it and while he took a leak, a soldier came in, watching him for a while. Turned out he had heard that musicians like the blues and the booze and smoking inspiring herbs, so he asked Mani for pot. He would listen to rock music whenever possible and he was eager to try pot. They looked each other straight in the eyes. Trustingly, Mani shared a pipe with him and after giggling in companionship they wished each other a good life. Nobody ever expected something like this happening in a GDR border toilet, stinking like a lion cage. The rest of us screamed at Mani for being too trusting and careless. If this one had been one of the wrong ones, all of us could have ended up in German democratic jail easily. All he said was: “I was sure.” What a time. Bright lights, big city, Berlin was flashing. Cut in two by a concrete wall, surrounded by an iron curtain, an island that never sleeped, 24 hours a day on the run. There was a lot I liked about Guru Guru and that stayed with me. We had gigs in France, so we hit the autobahn heading west. We arrived in Paris and found ourselves stuck in the middle of the most chaotic traffic around the Arc de Triomphe.

We finally arrived at the Théâtre de l’Ouest, the organizers gave us a friendly welcome. We played and earned us friendly applause, but no icebreaking moments or enthusiasm. Next band to play was Kraftwerk. Their setup was remarkable. Three neon lights from a hardware store, two microphones, a drum machine, echo and reverb unit and Florian Schneider Esleben with his silver flute and Ralf Hütter… They came onstage, didn’t even say hello and started playing. The machine gave the beat, the musical patterns changed slowly, the groove was hypnotic and the audience woke up. The hipper part of Paris youngsters celebrated Kraftwerk, two lonely guys, completely unpretending, just doing their thing no matter what. That impressed me. Another gig was at a French festival on an old farm in Roanne. A beautiful house with a park, apple trees, a huge circus tent and a pack of longhaired boys and girls in multicoloured outfits. There were kitchen parties before the gig with macrobiotic food, healthy, little salt, fresh french bread and a big pot of tea. No alcohol.

Everybody was smoking joints and a sweet young lady gave me a mug of tea whispering: “This is magic tea. Bienvenue.” Let me tell you, the tea was indeed magic, and slowly I started flying in a most pleasant way. I have no memory of the concert we played and the next day I drank a lot of clear water. On the way back we got helplessly lost in Lyon. It was like fighting your way through a traffic jungle. We got hungry and found a small bistro with green lights. Took a break. Got fed. And continued to find the way out of the jungle. Night fell. We saw a sign that led us out of the city. This moment Mani came up with the news that he forgot the bag with all our money in that green light bistro. Oh no. Back to the city jungle again. But in the moment we nearly lost hope we passed by a bistro with green lights. Against all odds we found the place and the bag again. I’ll never forget how the cover of the Guru Guru LP we recorded with Conny Plank in Hamburg, Windrose Studios, came to be. We got visitors from the USA. A group of Hopi Indians stopped by on their search for symbols carved in stone from Celtic times that show up in all parts of Europe and had a similarity to old Indian runes.

There was a lot of fun and dinners together with our groovy dancing guests. Big Bear told Mani to weave braids. Emma, a seventy year old shaman woman with fiery eyes, played games with us, puffing cigarettes one after another. Sharon, Ax’s girlfriend, was fascinated by both Emma and her Indian dresses. They started a conversation about aliens, sewing and beadwork. Sharon spent hours with her and everything merged into the new cover made by Sharon Levinson.

One thing I definitely didn’t like was dealing with other artists. There was always some kind of competitive tension, always quarrels about who or whose band got the best time slot to go onstage. This was stealing energy and good vibrations. It felt like stray cat behaviour. In my opinion it didn’t matter because if you play well you will get the audience anyway and it’s not really important if the sun goes down and the spots throw light. Was this fighting about who is bigger and better a German bad habit? Or just an alpha male thing? Macho posing? Artistism? I can’t tell. While working on the new album, we spent a lot of time in the rehearsal room all by ourselves. There was constant arguing, a kind of fight between titan A and titan M. Ax wanted to go more into rock ‘n’ roll and Mani tried to keep up the more floating and improvising parts. I myself seemed to be the punching ball in between them. I’ve never learned to discover the titan within myself and so my position wasn’t too strong. I remember a day when we interrupted work. None of us could argue anymore. Ceasefire. I vanished behind the mirror door. Mani somewhere else. Ax kept playing his guitar trying to get rid of his frustrations. First he produced an immense cloud of noise, spacy sounds, haunting echoes, cathedral reverbs. Then he changed into galloping power chords and rocked the shit out of hell. I have never heard him play so intensely before. Pure energy. Full power. Dancing rhythms. That felt so good to me. I liked it a lot. But I never told him. And then my time came. We played a concert in Heidelberg, a small festival. Kraan was onstage and rocked the hall, four nice guys, Jan Fride on the drums, Peter Wohlbrand on the guitar, Ingo Bischof at the keyboards and Helmut Hattler and his Rickenbacker bass.

The synchronicity of this band was fantastic, they had fun onstage, everybody could feel it. Me too. And when Helmut Hattler played his bass solo, he not only played the bass, he played with the audience, making them sing and shout. Mani invited Helmut to come to Langental. They jammed quite a while and I felt this constellation would be perfect. Without me. I immediately felt strange. I sensed this was a changing point. Sometimes it’s that easy. Weeks later, after the recording session with Conny Plank (he was absolutely the best sound engineer I worked with), I was more and more convinced that my Guru Guru days were numbered. The battle about the band’s direction went on between the titans, but I couldn’t mediate. All three of us were kind of depressed. Ax, one of the most honest persons I ever met told me that he was on my side. But Mani dreamt about changing the constellation and I got to roll with the punches. One sunny summer evening we were outside together at a campfire. It seemed no one had to say something. We stared wordlessly into the flames. It was Moebius and Rodelius from Cluster, also a band Conny had recorded. They came by for a visit. They sat beside us. High on whiskey, the shared bottle in hand and something in their blood that made their eyes sparkle. Instantly they sensed the situation. Very firmly they said, “Hey, you got to talk. Now!” And so Mani began to talk and my time with Guru Guru ended. 35 years later I sat on a tiny balcony of my grandfather’s house in the black forest, watching the diamond summer sky, burning tobacco. My mobile phone rang, unknown number. Normally I don’t accept phone calls close to midnight when I’m with myself. But this time I said hello. The call came from Berlin. It was Uli Trepte, the former bassist of Guru Guru. We have never before talked to each other. He had moved before I came to Langental and I only had this blurry memory of meeting him when we had a gig somewhere and we said hello. Still, we had an easy conversation, both knowing what we were talking about. We talked about playing bass and musical structures, the sexuality within music, the magical monotony of repeating basslines, and dancing with drum beats. We talked about Ax and his guitar playing, and his unconditional, nearly painful honesty. Talked about Mani. And we saw him the same way. A most inspiring drummer, an imaginative artist and the uncompromising godfather of his baby Guru Guru. Half a year later I got the message that Uli had died, may he rest in peace. Mani still keeps Guru Guru alive and plays ‘Der Elektrolurch’ even in Japan.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the bands? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

Walter Kirchgässner: Yes, the highest time, if you can put it that way, was the years in Night Sun. I am not “proud” of any of the songs, but of course there are favourite songs like ‘Come Down’ or ‘Living With The Dying’.

Is there any unreleased material by Night Sun or any related projects?

Walter Kirchgässner: No, nothing that I can think of.

What currently occupies your life?

Walter Kirchgässner: Right now, I am 70 and live as a pensioner in Mannheim, play the cello in orchestra and string quartets, read political, philosophical and theological literature, volunteer at the children’s hospice and still like travelling all around the world.

Klemen Breznikar

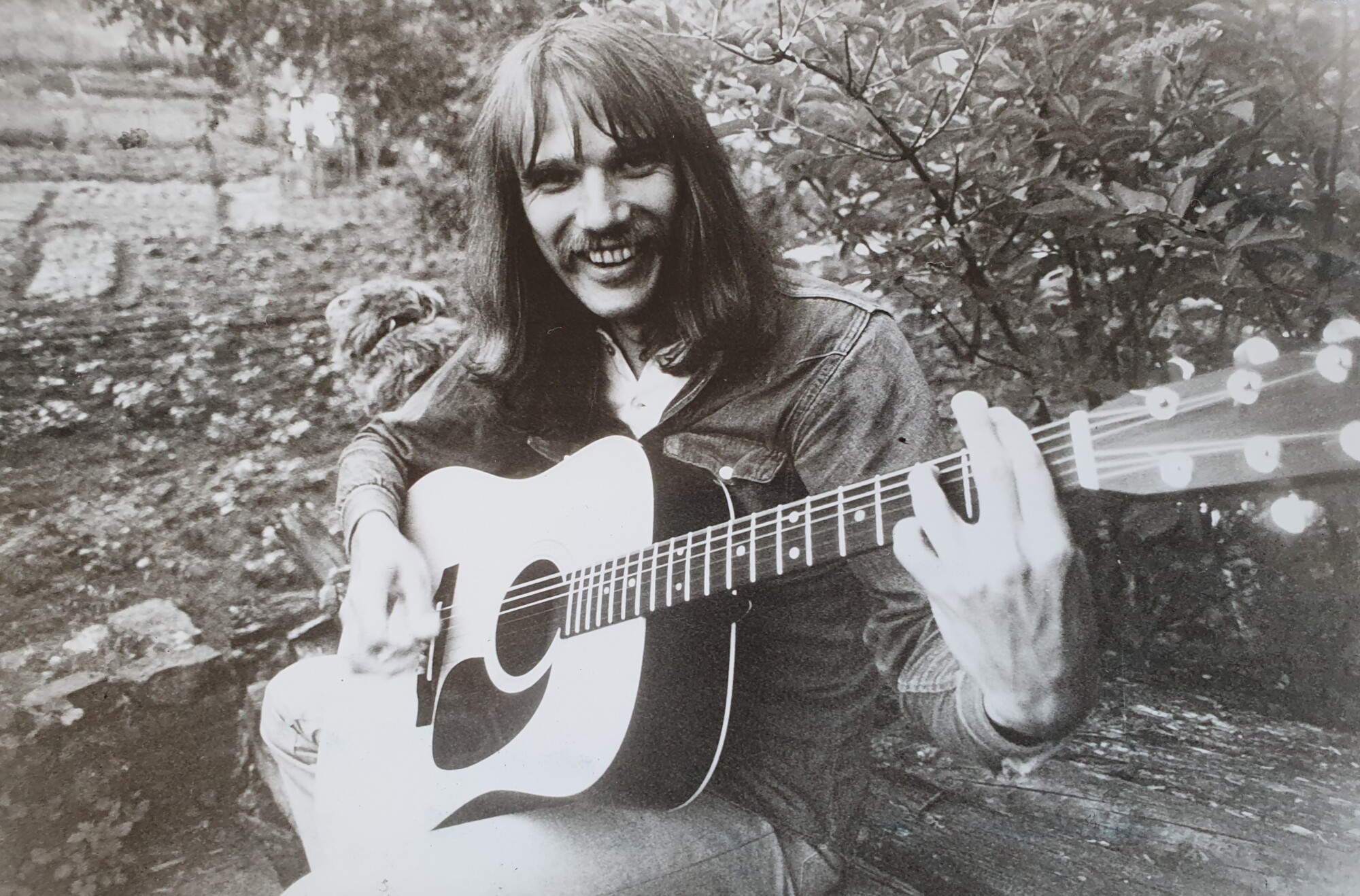

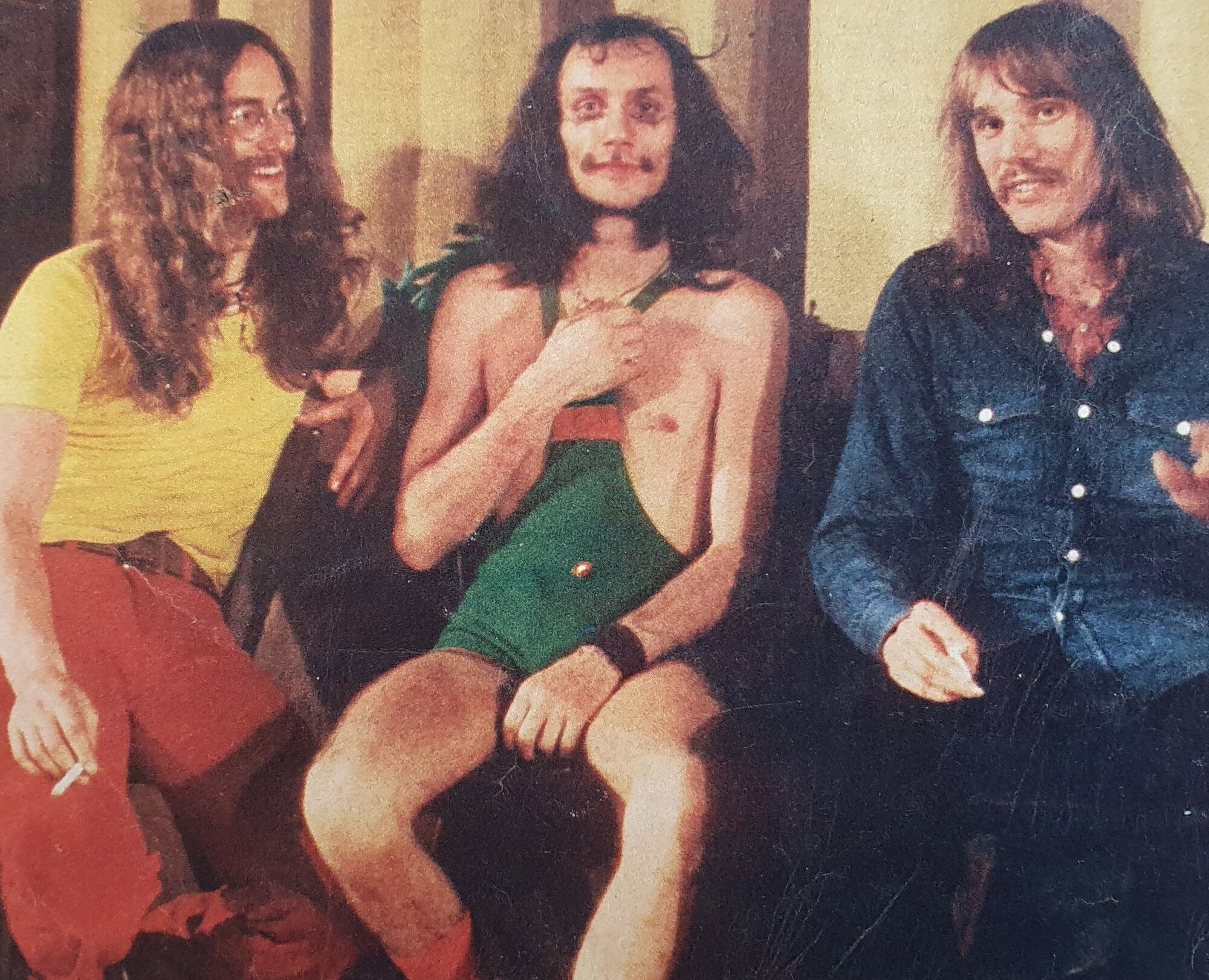

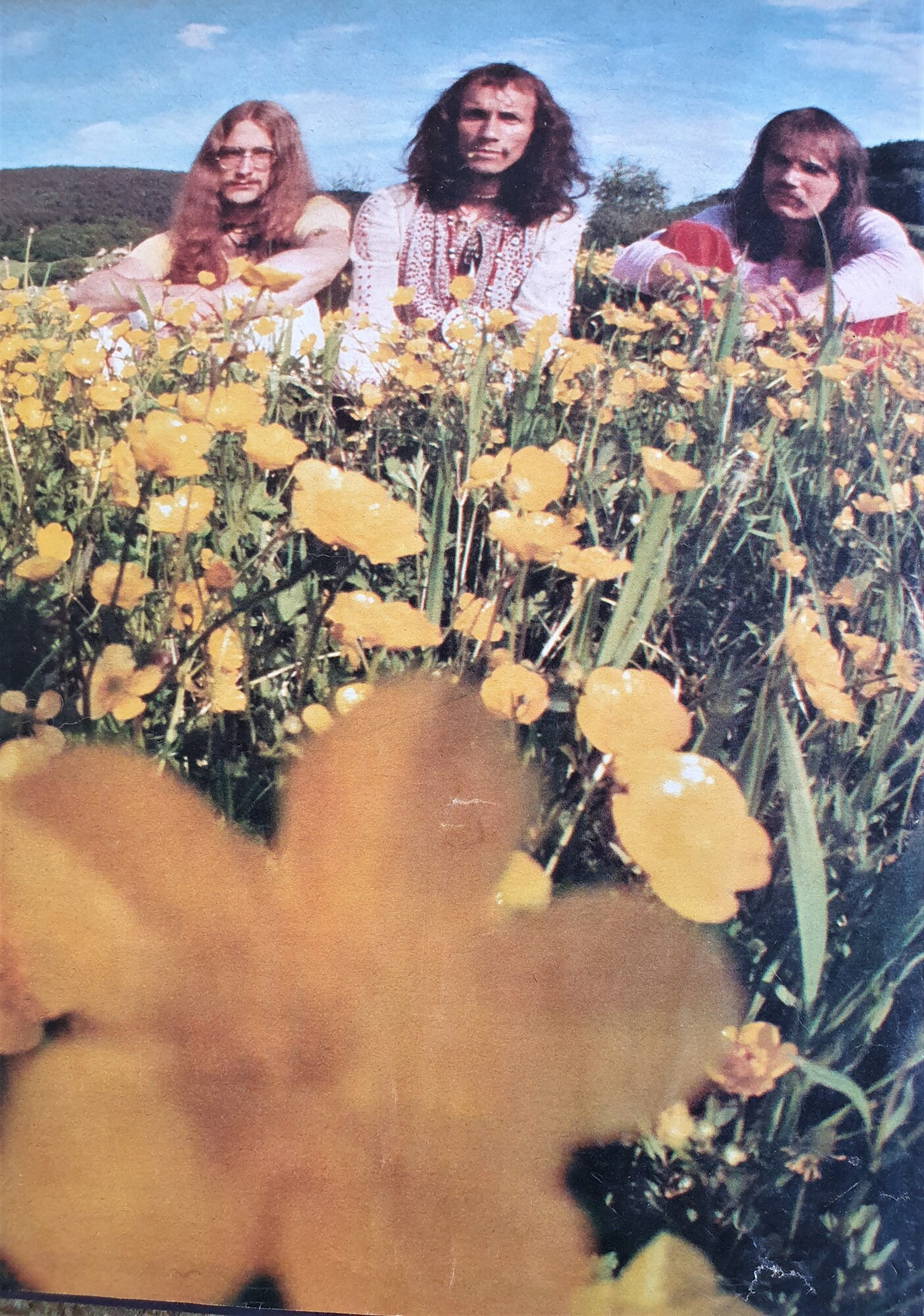

Headline photo: Night Sun (1972)

It’s good to see one of the most rocking and interesting obscurities from Rock’s golden age interviewed in the site. “Mournin'” is one of the finest Prog recordings from the genre’s heyday.

So good to see an interview relating to the amazing Night Sun after years of mystery! I tried to get in touch with members myself a long time ago. Well done Psychedelic Baby !!

Thank you so much, Rich. It’s nice to hear from you.

Wow, what a gem to accidentally find, then read. I found the Night Sun vinyl (Zebra) at Moby Disc Records in the California San Fernando Valley back in 1974. Absolutely great interview! THANX!

Wow, what a gem to accidentally find, then read. I found the Night Sun vinyl (Zebra) at Moby Disc Records in the California San Fernando Valley back in 1974. Absolutely great interview! THANX!