François Tusques | Interview | “If I don’t understand it, it must be good”

François Tusques is among the most important free jazz musicians from the old continent, beginning his career very early in the 1960s and continuing a rich body of work in the decades to come.

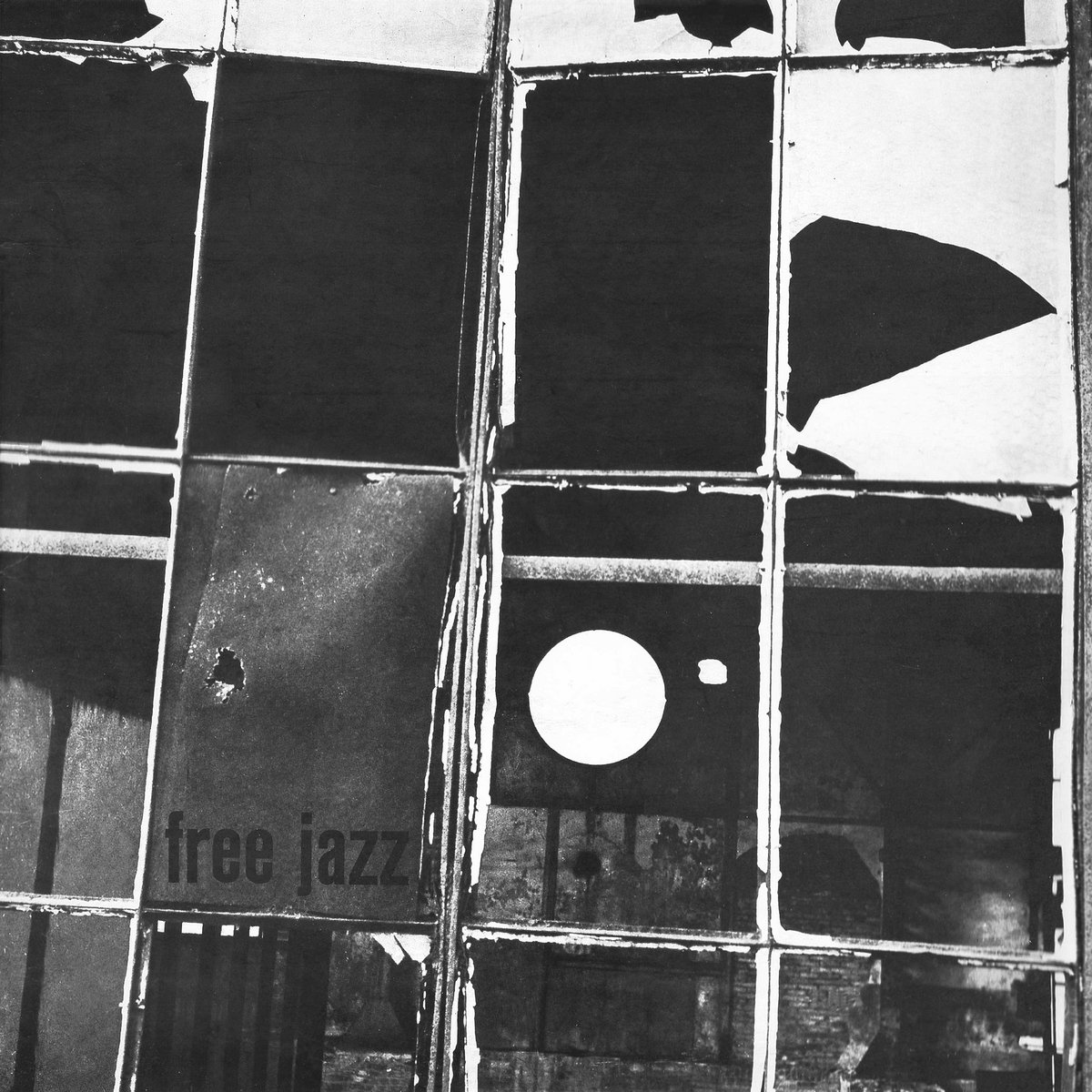

In 1965, Tusques recorded, with other like-minded Frenchmen (François Jeanneau, Michel Portal, Bernard Vitet, Beb Guérin and Charles Saudrais), the first album of free jazz in France, named appropriately ‘Free Jazz’.

In 1967, Tusques again served up Le Nouveau Jazz, in the company of Barney Wilen, Beb Guérin, Jean-François Jenny-Clark, and Aldo Romano. Tusques played a significant role in the emergence of a community of free jazz musicians in France

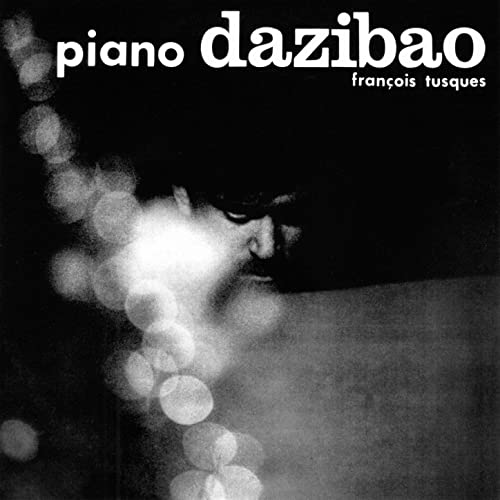

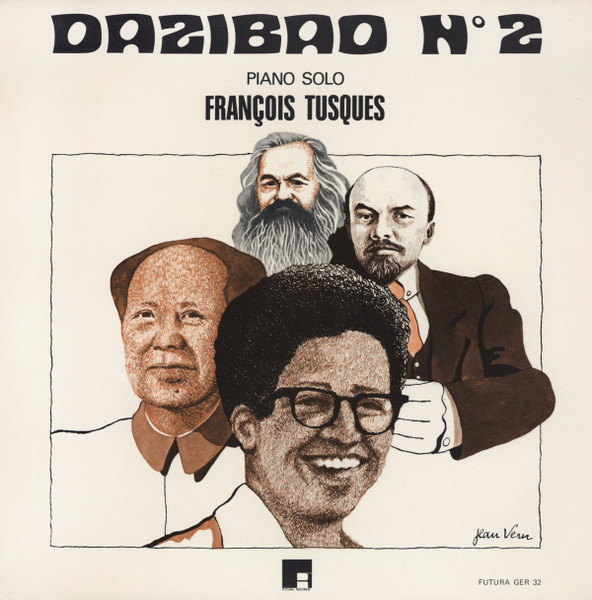

Three years later, between May and September 1970, the pianist recorded, at his home, ‘Piano Dazibao’, an album on which he multiplied joyful escapades as a critical iconoclast. The following year Tusques recorded ‘Dazibao N°2’, which shows him as an incisive commentator of his times. Following in the footsteps of Don Cherry, who he had met a few years earlier in Paris, Tusques made a plea for “friendship between all the peoples of the world” to the sound of Universalist hymns which transported us from Africa to Asia. But it is really a song to America, evoking the assassination of the activist George Jackson and the mutiny in Attica prison, before covering “Seize the Time” by Elaine Brown – three years after the release of ‘Dazibao N°2’, she became the first (and only) woman to lead the Black Panther Party.

More in the following interview conducted in May 2022.

“A loner, and a dreamer”

Would you like to talk a bit about your background? Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life?

François Tusques: On these matters I don’t have much to add to what my “official biographies” here and there already state. I was born in 1938 in Paris, the family quickly moved to Brittany – it originated in the South of France, though. From where, in the 19th century, distant Tusques migrated to the Americas. There’s a branch of the Tusques family in the US that I finally met 10 years ago when William Parker took me on tour, and I have a distant cousin, my age, who’s a cocktail pianist by trade…

Your mother was a singer at the Paris Opera, so the environment you were growing up in was filled with music.

Yes, and no. By the time I was born, my mother had taken time off to raise me. She never got a chance to return to her career as the war broke up soon after. We moved back to the ‘Free zone’ in the South, and my father was very active in the Resistance. After the war we moved around a lot, and some of the places we settled in were musically pretty quiet.

She recorded in the 1930s but I couldn’t locate those records.

Can you tell me more about your Father – doctor and professor, Jean Tusques. He was active in the French resistance movement…

He was a famous psychologist. His work is still a reference… in Italy. Paranoia, and also hormones and the child’s development, I think, were his specialties. How famous he was I really realized at his funeral in the 1970s. Hundreds of people turned up. Nobody knew who I was exactly (he had remarried) and I mustn’t have looked too good as people enquired as to who I was with a clear intention of throwing me out. He was a public figure, a famous teacher, a busy man and we were mostly estranged. He was somewhat embittered after the war, for political reasons, hence the prolonged periods of exile the family went through – he wanted out of France. Or had no choice.

We mended our relationship in the 1960s – at first he was distraught. I had become a brothel pianist in the 1950s, but later helped me maintain some form of housing or another when I had a child. Mother died earlier.

Later on your life was marked by many trips to Afghanistan and Dakar. Do you think that experiencing other cultures early in your life influenced you as a musician?

If it did anything to me – it was to make me kind of a loner, and a dreamer. A loner for I didn’t go to school till I was 10. It wasn’t easy for me to adapt after that, and I graduated very late… Not that I wasn’t interested, I tried hard, but I had so to say forged my own intellectual reflexes and often lacked direction.

But of course, the landscape, the adventure… Afghanistan in the mid 40s was still pretty much the same as it was at the onset of the Islamic civilization. Fierce horsemen flaring swords, I’m not joking you. There was one road in the whole country, and here we are pushing a battered car through sandy tracks with a watchful eye on the water supplies. My father created a huge dispensary from scratch there. There was a cinema with a good assortment of American blockbusters of the days in the foreign, locked down part of town though. We sailed back through the Suez Canal, barely avoiding wreckage, it was indeed the ship’s last voyage before it sank for good on its next outing. I had befriended the crew during those long weeks. They all died. I often think about them.

When did you move back to France and what were some of the first artists you listened to?

We returned in 1950. There was classical music at home thanks to my mother. Still, my real awakening was Bechett with Claude Luter at the Olympia that very year. I was into Sydney and soon into New Orleans. My parents had the means to, and indulged, my record buying frenzy. By 17 I had roughly 200 New Orleans records, and exploring obscure corners of the 20s and 30s served my own practice a lot, I guess.

So I began on… the clarinet. I dabbled in double bass too a little later. We moved to Dakar for a short time when I was 17, 18, as it was obvious I’d fail to get my high school diploma. There was a piano there, I made some friends and they turned me on to Parker and – we tried to “parkerize”! Back in Nantes I sold all my New Orleans and I started playing the piano in earnest. Diz, Monk, Bud, Bird. Playing to the records, the old fashion way.

Soon I started my local Hot Club branch. 56, 57 or so. My mother helped me get a few music theory lessons on top of that, thanks to her connections. I had a pretty rigid lady teacher – Debussy, Ravel, Milhaud, the kind of stuff my mother was good at. I was finally interested, though it was sketchy, with starting to earn a living and all that. Yes, it was a very rigid frame and – I loved it! It suited me. I’m a hard worker. And I need to be shown hard work. Otherwise I lose interest…

But, all in all, I took one week of piano lessons in my whole life. One week! Mother had enrolled me in a seven days practice crash course after those theory lessons. I don’t remember any of that. While hanging in Jazz Hot’s offices later, I chanced upon Errol Parker who also gave me ONE (expensive) lesson. Late 50s, those were already the days of Blakey, Roach – I was into this percussive approach. And Urtreger.

In France you didn’t have the army band, so my first stents were dance. Independence Day, weddings, the like. It stuck with me, those are the roots of L’Intercommunal and of my brush with strictly traditional/folklore music in Brittany in the late 70s. I may have grown “jazzier” in my old days but give me something to dance to anytime. And I always hope that my audiences first and foremost enjoy themselves. I hate to put them to sleep and see them with a serious frown on their faces.

France was the only country in the world that had a huge love for jazz music at the time when jazz was still completely ignored by the US. Why is that, do you think?

Making amends for its structural racism, maybe? A POC is as good as their art, it’s easy to celebrate the “genius” of this and that people, and treat the non-artists as underdogs.

In a context of cultural war, as Europe was economically nearly finished by then, all Western Europe could do was to more or less signal its own moral virtues to the US. As in, “we’re still culturally above you, we can even ingest what you reject”. Meanwhile we were doing ugly things with “our own” (as if we “owned” them…) POCs. I fought a stupid war on those grounds, so I’m wary of France’s appreciation of other people’s art.

In Nantes you formed your first group. Tell us about it.

It was a process more than a decision. I was jamming with this Pied-Noir dance band in Nantes in 58. Lots of disreputable places, brothel gigs, actually… I couldn’t even read music, it was the accordion player who would shout chord changes at me in mid-flight! ‘Lucien Atar et l’Étonnant Fantaisiste Totor Vendaire’ … My playing was erratic but had enough harmonic invention for me to fit and receive accolades from the leader.

So we traveled. I can’t recall exactly, but we went to Switzerland. And Jimmy Gourley was stranded in a club without his rhythm section. I filled in with another cat – Bernard “Beb” Guérin. Gourley fired me on the second night, I couldn’t play… much. He kept Beb though, who was already a highly trained double bass player. And we struck up a friendship.

Gourley was a good guy though (or was it a practical joke on a hated colleague?) and recommended me to Belgian sax player Jacques Pelzer. As it turned out, Pelzer was a strange character, a pharmacist and chemist by trade. His homebrew scared the shit out of me and I was out in no time with a peculiar distaste for the world of drugs.

I had a real nerve. I was nuts in the late 50s. I already had to leave and would try anything. I even crashed a few gigs with Chet. After we went through the three standards I could manage more or less decently, he seemed happy enough, but I had to leave nonetheless: I couldn’t even understand the name of the tunes he shouted at me during applause…

“I still strongly rely on the attack and the rhythm, and I have no problem with melody”

Your first gigs were with François Jeanneau, Luigi Trussardi and Michel Babault.

Exactly. Trussardi and Babault were beginners and I was getting serious about my playing. I figured out it was the only job I’d rather do. I wasn’t too good at anything else (especially dealing with authority), so why not that. I was aware I didn’t have the incredible phrasing of my favourite pianists, Jimmy Yancey, Earl Hines, Jelly Roll, Ellington of course, but Monk showed me I could be something else anyway. I still strongly rely on the attack and the rhythm, and I have no problem with melody.

Note: it was actually Babault and I who invited Jeanneau and Trussardi, who were replaced with Beb! Babault was a tall, lean figure. His secret dream was to be… a car mechanic. He was already fed up with jazz. True to his word, he had his own repair shop before the 60s were over! Anyway, I bought a dilapidated house in the suburbs of Nantes, we lived together, the three of us, Babault, Beb, me. We could finally rehearse properly. Sometimes with Philippe Combelle who was still a saxophone player, before he became a gifted drummer. Likewise Beb decided he was gonna be a pianist, too! I talked him out of it. We were young and trying to find ourselves and develop.

When did you decide that you wanted to start writing and performing your own music? What brought that about for you?

It just so happened. Monk’s music encouraged me to do it. And later, Bud, it must have been 63. We never really talked. He had me sitting by his side on certain gigs to show me the moves. No explanations. Just watching the moves. It helped not only my playing, but it also gave me a few ideas on how to compose, based on – moves. Symmetries. Gesture.

The Americans were interested in that. But at first it didn’t sit too well with the French…

You went to Algeria for Military service.

No. I went to Algeria to fight in a nameless war. After dabbling in “the Left” for a while, I was finally formally exposed to Communist ideas here, and that’s the only positive thing I can say about it. I’m lucky, I was in the Signals and communications corps, not on the field. Still, what a mess. When M.A.S.H. was released, I was dumbfounded. It was it, exactly it. The only problem is that while we rank and file were doing our best to make it a surrealistic (drunken) experience to keep our sanities, people were getting murdered by the thousands.

After returning back to France you fully occupied yourself with music and moved from Nantes to Paris. Tell us about those early years in Paris. What was it like and who all did you play with around that time?

I was a raving madman, full of rage when I returned. I couldn’t stay in one place, I was going to and from between Saint-Nazaire, Nantes, Paris, Angers, Poitiers, a nomadic lifestyle with Beb and the like. Politics and free bop.

In a sense, I didn’t have a lot of time to enjoy what was happening – I finally settled in Paris with my wife Françoise, she got pregnant, and I needed to work more than ever to provide. Back then (was it ever different?) making a living out of music, you were mostly missing on anything that was not “your gig”. When you got hired, you earned your pay the hard way – from 6pm to 2am, five, six sets…

It wasn’t enough to feed the wife and kid. I was a typist and copywriter, and so was my wife. We took shifts to be able to work up to 20 hours a day. Later I worked for Libération and Actuel. We had this room up there in the 18th arrondissement of Paris, no running water, no bathroom, no toilet, and a constant turnover of people. Visiting musicians – skip to 1969, there was a point when we had army stacked beds in there, with Barre Phillips and Artur Jones and others, living off cold canned food (especially since Jones was convinced the CIA was trying to poison us). Nevermind, we played our jazz.

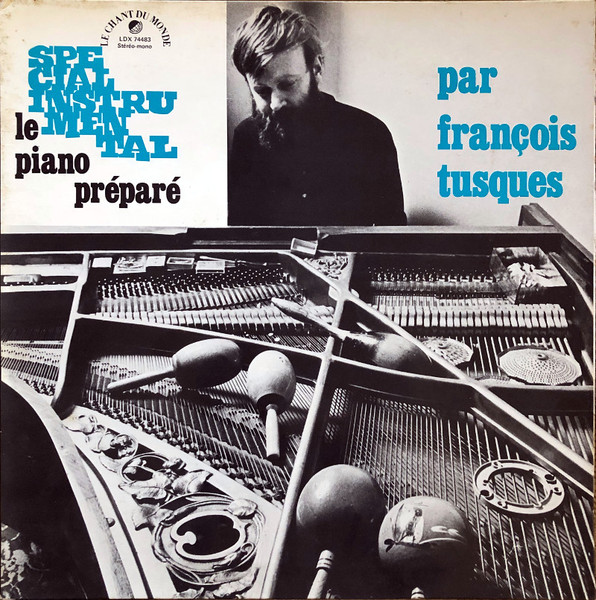

I’ve kept the room since 1965 and I’m still there. Water reached my floor sometimes in the 1970s and I was able to buy the joint for next to nothing in the 1980s thanks to my first TV royalties. ‘Piano Dazibao’, ‘Le Piano Préparé’, up to ‘Générations’ and even ‘Avants-Derniers Blues’ – lots of stuff was recorded there on this 6th floor! Still no elevator, please.

How did you get in touch with Bernand Vitet, François Jeanneau, Michel Portal, Charles Saudrais, Bernard Guérin?

Downtime, between the gigs Beb and myself shared. Vitet was our age and hung around the same jazz spots – he was already a noted accompanist in the booming industry of chanson, and in-demand as a session man.

Actually Saudrais and Portal came through Bernard. I literally hijacked his band and even though we were billed as the Bernard Vitet Sextet, as I had provided nearly all the originals, when it came to release ‘Free Jazz’ he decided I had to take full credit even though I still considered myself an absolute beginner.

Nevertheless when it was his stuff we continued to bill ourselves as his band. The strategy was to get hired as many nights as possible under different guises… Around the same time the whole band minus me even recorded for electroacoustic composer Bernard Parmegiani. It was all very flexible.

This group recorded their debut album, ‘Free Jazz’. It was released by Mouloudji. What can you say about the composition and where did you record it?

The music we slowly put together during stints in Paris in late 64, early 65. You’d be surprised listening to the surviving cassettes of those gigs – we were churning out some pretty well-behaved, neat hard-bop.

Mouloudji, a successful singer, I met through Colette Magny, and he granted us independence, albeit with a very minimal budget. It wasn’t much of a studio and I’m sorry I can’t remember exactly where it was located – I have the masters but it’s not even written on the boxes. So we recorded this average music – great playing, but not much of an interesting structure – and I slashed my way through the material at the mixing desk. Scissors, glue, careful layers, I took the whole session apart and reconstructed it with the band’s assent – as I told you the others were later to work for Parmegiani, we all had an ear to these new forms of contemporary music.

Not that I wanted it to be contemporary music – I think I did a good job keeping it jazz. It’s just – we wanted to build from these blocks the music that we envisioned rather than the music we could actually do. And at which we got better and better afterwards in live situations. It gave us the pattern. This is Dada. I love college. I’ve played such tricks numerous times. A record is a record, it doesn’t have to be the truth. Imagination is important to me. You can’t always go where you want to go during the gig, because during the gig you have the audience in mind, you’re not looking inward.

I absolutely adore the cover artwork. It gets me every time. Was there a story behind it?

Me too, it’s one of my best! Yet – all apologies, I can’t talk about it. Because the photographer doesn’t want his work to be discussed and his name to be mentioned. It would be a long story, and he insists the story can’t be told. Over the course of a long career like mine, you’re likely to get into odd situations. Neither good nor bad, just odd. Being a keen personality I have a tendency to get into such situations easily.

I can’t leave out that your album reminds me a bit of Eric Dolphy’s ‘Out To Lunch’.

I’m glad it bears some resemblance. Andrew Hill I met later, and we toured together. This new generation of pianists, Hill, Waldron, et cetera, I really felt at home there.

None of us had listened to ‘Out To Lunch’ at the time though – Blue Note didn’t always reach France immediately after their release. Let’s say it was a trend, an idea that was floating around, friends confirmed that the same ideas were also brewing in other parts of the world like Japan. It was a logical extension of ideas that were already there in hard bop and modal jazz.

By then, we had listened to Ornette and Don Cherry of course, and that was roughly it. Now, if you allow me to confess an influence – it’s this slightly out of character album Chet recorded with Dick Twardzik in the mid 50s, ‘The Chet Baker Quartet’. A French release. It’s cool jazz that’s getting angry, forbearing free jazz. Check it out.

“If I don’t understand it, it must be good”

At the time you also played with Don Cherry. What can you say about his music and did it influence you to a certain degree?

“If I don’t understand it, it must be good”, was my first enthusiastic response.

Although I suspect that Don picked me to piss off everyone else in Paris, as the aforementioned response wasn’t widely shared – at first, “they” all hated it. Hating the new music was the fad.

Anyway, I credit Don and later Sunny Murray for reinforcing that feeling in me: “If I don’t understand what I’m doing, then I must be on to something”.

I still compose a lot but throw away an awful lot of music as well, because of this precisely: if I have something to say about it, it’s a goner. If I don’t know what to think, it’s a keeper.

Both Don and Murray made me aware of chance, of coincidences, of many things beyond the mere practice of music. It’s very difficult to explain. I would have to show you on the keyboard, actually. Or I have to write a book about it while I’m still around. I have tried repeatedly, I have even managed to teach some of those quizzical ideas derived from Don and Murray to students, and it’s not at all mysterious and difficult, but it’s so gestural you have to see it to get it.

There were a few bumps in the road in our relationship. Beb and I were slated to be sent to NYC to be on Don’s Blue Note debut. Budgets being budgets, he downsized his band to Karl Berger and Aldo. I love both of them and have subsequently worked with them, no qualms, but I decided to sever ties with Don. I was young. It was probably stupid of me in retrospect, I took some bad decisions now and then, like refusing to record for BYG. But on the spot, it was also probably the right decision, if only to achieve some self-respect. We mended our relationship soon after, I offered him to be on Le Nouveau Jazz but he had to take on a gig that paid better; nevertheless he appreciated the gesture and as you probably know, I’m a ghost on his ‘Mu’ session with Ed Blackwell. I’m sitting at the piano, and when Don blows his trumpet and bugle in the piano, I’m working the pedals to achieve a reverb effect and vary the depth of sound. I’ve done lots of things like that, like recording a piano part, have a band improvise on top of it, and then erase my parts from the final recordings. I don’t insist on being there at all prices. I’m this looming presence…

You continued to work on so many releases. Would you like to name a few that stand out in your opinion when talking about the 60s and the early 70s?

I tend to remember the gigs more, because with characters such as Alan Shorter, Sunny Murray and Alan Silva, or Vitet and Jacques Thollot, there was always something uncanny, scary, and interesting going on. Driving in my Citroën 2CV to Lyon with Alan and Murray in January, the double bass sticking from the open roof, Murray burning newspapers in a pan to prevent the bass’s wood from freezing and exploding…

Well, the Murray, Thornton and Magny records were important music, more than my own probably. I read some argue my “influence” is all over them but it has nothing to do with influence whatsoever. Without the great catalysts they were it would all have amounted to nothing. I provided ideas and they taught me a lot on how to develop those ideas in the process.

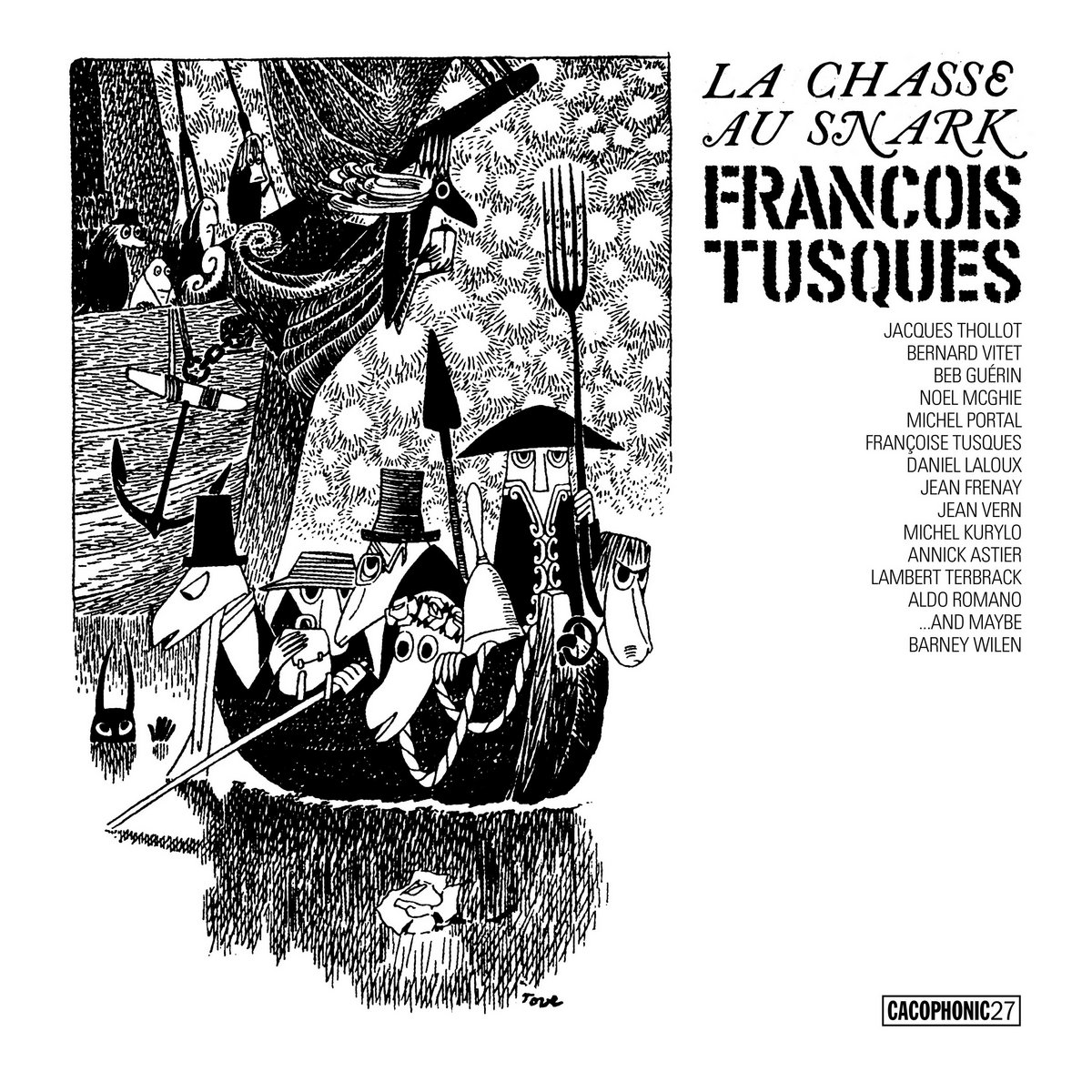

You have to understand that between 67 and 70, while I was on all those great albums and peripheral to the BYG adventure, I didn’t get a chance to record under my name. In the 1960s, three years without a date as a leader was a huge, almost deadly gap. But was I ready? When I wasn’t playing with the African-American friends, I was busy putting out “happenings” with my own crew, Vitet, Beb, Barney, Noel McGhie, Laloux, actors, visiting friends (like Jacques Higelin) – we held this endless series of concerts losely revolving around Lewis Carroll’s poem The Snark, but I could never design an appropriate form to commit that to record, much less get a producer interested. In 1970 and 1971 I even got some of the BYG cast involved in this ongoing series, – to the same effect, it wouldn’t congeal. Finders Keepers finally released most of the surviving fragments on LP in 2019, so I take the occasion of this interview to thank Andy and Doug for their efforts. This is the lost 1960s album that you never knew was lost because it didn’t even exist!

Would you like to talk about ‘Dazibao’? ‘Dazibao N°2’ has a provocative cover…

They are cassette home recordings. I have already mentioned the stacked beds – the rest of the room was taken by a grand piano! I decided to get Cecil Taylor and the African music I had absorbed through Don out of my system. And some of the melodies that were built within the Snark project.

A few cuts were left out due to birds chattering and the garbage trucks clattering through the open windows.

The first title I came up with was ‘Epiphanies’… Divine revelations?! Terronès objected… Consequently we overdid it with the artwork of ‘Dazibao N°2’… I could discuss politics here for hours, but it would take us someplace else.

(Someplace some people refuse to go. I recorded ‘Le Piano Préparé’ in 1972 immediately after ‘Dazibao N°2’. The record company found the liner notes so politically infuriating that we negotiated them word by word for five years, hence its 1977 release. When nobody cared anymore).

Fun fact about ‘Piano Dazibao 2’: a significant amount of copies were consigned to a chain selling household appliances. The idea was to give away the album to buyers of hi-fi systems. As it turns out, it was mostly given away with fridges, ovens, coffee machines… and unsuspecting house moms duly canned this horrid commie music. That’s why you won’t find many originals on sale.

Also, if you ever find one, REQUEST THE ORIGINAL FRIDGE BE SOLD TO YOU WITH THE LP.

Or get the Souffle Continu reissues. I like the sound better than the originals, which are a bit muffled. Back then Gérard did all he could to rescue my cassette “masters”. Nowadays it was a proper move to alter the sound a bit “upwards”.

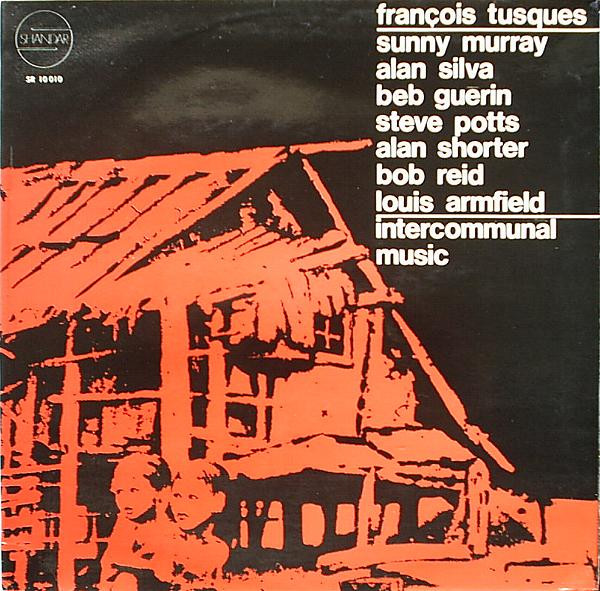

What about ‘Intercommunal Music’?

Mayhem. It was four years since my previous appointment as a leader. I finally got a decent deal for me and Beb, Alan and Sunny. Piano, two basses, drums – an idea I wanted to explore.

45 minutes before we had to clock out, Alan or Sunny – can’t remember which one of them – hadn’t shown up yet. 44 minutes to the deadline – enter this cast, Steve, Bob, Louis, Shorter… Out of desperation, I ordered the nonplussed engineer to start the tape. Shorter decided the sound of the room was crap and opened the door to an adjacent courtyard and blew hard from there. Murray saw it was multi tracked, said it was bullshit, and threw away the forest of mikes surrounding the drums. 38:30 to the deadline, the session proper started. 00:20, the raging engineer, who had left, returned to point at the clock, we hit a few notes, that was it. No outtakes, that’s for sure!

Murray mixed the album with me and showed me how to reconstruct a natural/surreal drum sound from, precisely, the MISSING mikes – it all bleed from the few mikes that were left, giving this compact, massive ensemble sound. Reflections of his drums in the piano, the horns, the walls… I was sold forever. I have never ceased to experiment with recording techniques, including recording big bands with one mike suspended to the ceiling. I don’t like the studio much, if I can I avoid it. I prefer live settings or home sessions.

The album is what it is. I’m OK with people seeing it as a milestone. I don’t exactly understand this album, but as I said earlier, if I don’t understand it, it’s probably there is something to it.

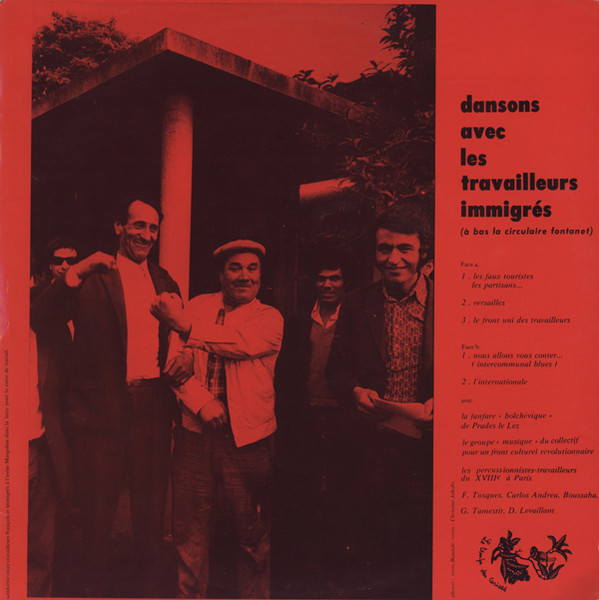

There’s a whole series of Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra releases. Would you like to share what was the basic idea behind this orchestra?

It was 1972 and I felt an itch – maybe we, the free jazz people, were starting to go round in circles. It was all valid, but what next? I wasn’t only a free jazz/jazz artist. I had been working with Colette Magny, and had dabbled in film music. And I had political ideas, as you know… I was not the die-hard activist people nowadays think I must have been, but still, I was confused by the fact I couldn’t take my music outside the clubs and this circle of “people in the know”. Also, I had never reneged my days as a dance musician.

The diversity of background in Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra adds a very special flavour to the releases.

Through political circles and friends, I had met Africans, Algerians… You see where I’m going. Synthesis, like in Marxism. I wanted a flexible band to play in factories to workers, in the fields to farmers, that would appeal to other people, music to dance to, to mingle with other bands from other musical horizons. Everything could and would go in there. Folklores – fanfares (we crashed a visit from the President to the Larzac, a famous anarchist commune: we welcomed him with the Internationale, of course) – traditional singers from Brittany – Tanguy and Jean-Louis of course – Algerian percussion – African drums and trombone (Ramadolf, Togo) and sax (Jo Maka, Guinea) – some jazz obviously, my jazz and – jazz of other areas in France (Michel Marre). Later on Carlos Andreu, Mirtha and Pablo, and even – back to free jazz with Coursil, Oki, Dumas… The list is too long for me not to forget some names, all apologies!

No constraints. I brought the tunes, they did the rest. In and out of circumstances were active from 1972 to 1984, with the occasional reunion afterwards.

Sidenote: I thought and still think free jazz can be popular music. It’s how you present it and to whom.

Where does your love for poems by Federico Garcia Lorca come about?

It really was a commission from Nato’s Jean Rochard, who lived with Violetta Ferrer at the time. Great people there!

Later on, with Wiart producing, Octaèdre – Cortazar, it’s me. Cortazar, Robert Walser, Jean de la Croix, and again Lewis Carroll, those are important writers to me. I’m an avid reader.

What can you tell us about the two albums by Le Collectif le Temps des cerises?

See above, this the Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra version 1. On a sad note, I’m sad I lost Beb at the inception of the collective. He didn’t understand what I and the others wanted. Jazz was his horizon. He relented, I fired him. I was not always an easy person, what with the financial pressure and all. We kept in touch but it was not the same. He took his own life much too young.

What can you say about the recently reissued album by SouffleContinu ‘Alors !!!’?

I’m afraid I don’t remember the album so well!

Portal is undoubtedly an important musician. When he was working with me, I admired his stamina. We got along together because he was a hard worker too, he learnt the bass clarinet literally in front of me, in no time – he had a horn in his mouth 24 hours a day.

We had our disagreements in the 1970s, his insistence on classical and contemporary music… I said so publicly on the radio, maybe I had to do it in context, but in retrospect… I grew to be more lenient in regard to all this…

What about ‘La Guêpe’?

I was far more comfortable with that. Those were experiments we had started together in the days of the Snark. There was a strong element of fun. I could play the violin, the saw, Bernard was an early proponent of tape delay, he would devise metallic reverbs out of old buckets (in which he had a tendency to have me sing, as evidenced on the aforementioned Snark LPs). He’s on all the chanson hits of the late 1960s, early 1970s, Barbara, Claude François and the like (Claude François jammed with us, it was captured by Jean-Christophe Averty, aired once and probably destroyed by the singer himself), but on the other hand, off duty he balanced it with a craving for the bizarre. But it remained elegant. He knew when and HOW to quit. It tastes good.

I think his final performance was with me. He couldn’t play the trumpet anymore but had brought his customs electronics, it was still far out and absolutely Bernard. I wish someone would release that concert.

There’s a pared-down version of the material in the ORTF/INA vault, some of it is available for download on their website. The vault contains other material from us. I hope it sees the light of day too.

Would you like to comment on your piano technique? Give us some insights on developing your technique.

As I said, I ought to write about it at length. I have enrolled a few friends to try putting together material for a book. Maybe we’ll film a few things, too.

I’ve already given you hints discussing my stints with Don Cherry and Sunny Murray. Let’s say I have often used the same mode from the 1960s on – it’s a nine notes mode starting with the black keys, and various transpositions of 5ths and 7ths. I slowly became aware that whatever mode I used on the right hand, pentatonic, major, et cetera, while using this mode on the left, there was always enough correspondences to avoid dissonance, while keeping things different, eery… Moreover I realized I could “import” any tune within our outside the jazz realm into this mode, and transpose those tunes into oblivion through transposition. My music is full of quotes people don’t even suspect.

My improvising skills, if there are any, rely heavily on serial thinking.

Oh well. Besides, my favorite relaxation is playing the Blues. In B flat. Why? Because you’re not supposed to.

Back to the nine notes, I think it’s some kind of poverty art. The twelve-tone, microtones, that’s too much. To me magic is when things disappear, they’re felt but you have the pleasant or unpleasant surprise to hear things go someplace else when you expected least. It’s also a tribute to all the bad, toothless pianos jazzmen have always encountered everywhere. I love their flawed pianos! A missing note, a sloppy tuning, a dead pedal, those constraints fire my imagination. It’s coming to the point I’m scared of collector’s items you are sometimes given in the studio or on stage.

What are some of your albums and collaborations that you’re most proud of?

I’m not one to not enjoy what I’m doing. I’ve been lucky to be in a position to choose most of what I took part in – because I had a steady source of income from the 1980s on with TV, film and stage work. It’s difficult to pick anything precisely. I should thank Isabel Juanpera, Denis Collin, Danièle Dumas, Noel, who helped me create the music I had in mind in the 1990s. When I thought I would retire quietly I accepted Julien’s offer to record for his label Improvising Beings – Julien is the one transcribing these notes in English – and it was another adventure with old and new friends, it would take us pages and pages to recount all that. I’m proud that these new albums sold, even in China and Argentina for all I know. And it continues into the 2020s with releases of old records or unpublished stuff. I am glad for all these bonuses and new chapters.

Maybe I will have a special thought for the American Tour I undertook a decade ago thanks to William Parker, with Hamid Drake, Kidd Jordan and Louis Sclavis whom I rediscovered through a new light. What a player! It was gruelling, driving, I say DRIVING hundreds of miles across the USA to rush on stage straight from the car, but it rekindled my interest in improvisation and ultimately free jazz. I’m gonna be honest: it was heartening that some of my music, even though I have ceased playing like this ages ago, still meant something to these musicians, and the public.

What is “free jazz” in your opinion? How would you define it?

I have no doubt it is something. That it took its name from a record is somehow confusing, but my understanding of it has never changed: it is first and foremost political. I can’t forget we were collectively putting out a fight against many a form of discrimination, against apartheid, we were showing we were a force to be reckoned with.

So naturally we had to question the form(s), whether we could keep this or that building block. Were standards, chords, harmony, things we could relate to, or were they just another manifestation of domination, capitalism?… We kept some, rejected some, the idea was to constantly debate it.

In the days of BYG we had raised so much fuss that even the record companies were starting to pay attention. Some even assumed there could be money in it – Pathé released Ayler on 45! What a gloriously funny misunderstanding.

Do you discover new aspects of your songs developing in front of an audience?

I have always been through a compositional process first. As I said, I compose a lot. I know what to discard as soon as I have finished trying it for the first time! Whether I plan a solo performance or a group performance, I rehearse a lot. If I do so it’s to make sure, not that the material’s gonna be played note for note, but on the contrary that everyone has internalized the basic idea and will be absolutely free to take it wherever it has to go. Naturally so to say.

But in a sense this is a way not to have to develop anything in front of the audience. I think of the audience beforehand. I’m shy, I can have stage fright like anyone else, and I don’t play often enough to make people unhappy with music that meanders out. It’s not about perfection, but I owe the audience that respect. I guess I feel like they expect a bit of control from someone who’s been at it 65 years.

That said I rely a lot on the other people in the group to make the repertoire theirs. There’s a bit of laziness in it, “I’ve already done enough”,… but it’s also that I enjoy rediscovering my old tunes in new colors. If I enjoy what they’re doing I can lay off for minutes.

One of the most recent releases is your album with Isabel Juanpera, Itaru Oki, Claude Parle.

I managed to keep this quartet with Isabel Juanpera, Claude Parle and now Nicolas Souchal together and rehearsing during the pandemic, and we will soon record it again.

This quartet indeed started with Itaru Oki in 2014. He passed shortly before the pandemic, it was a shock and we collectively felt we owed it to him to present what we had started to work on together.

After years of instrumental music I felt like returning to a song, poem and music format, like in the 1990s. And as I was putting together the Snark archive LPs with friends, I felt I owed my young self to revisit the Lewis Carroll material again and finish the job properly, hence the Jubjub album.

In 2017 and 2018 we recorded a second album that is a meditation on the May 68 revolt, in relation to more contemporary matters. It will be released later this year by Antoine Prum’s Ni-Vu-Ni-Connu label.

I’m ready to record the third album. Some of the content may be considered political. Improvisation is more prominent in our current incarnation.

How would you compare your older material to the latest projects?

You’d think I of all people ought to know? Far from that. I enjoy my old records and gigs archive, I have favorites, I can easily recall what I was looking for, how it happened, but it’s almost as if it was someone else playing. I always have so much fresh music in my mind, every day, it’s almost painful to get it all out and I never take the time to look back.

Of course there’s the accumulated experience, I’m not throwing myself into the piano like in the 1970s, I tend to think more. But back then I also did lots of thinking, so I can’t see a real difference. I’m aware my playing slows down but I’m always minding it, and practicing. I’m a jazzman, I like to deliver a good, fast right hand line.

Your finest moment in jazz?

If you allow me to circle the question again – keeping myself and the audience interested have always been my main concerns. As a consequence I’ve had fine moments on a battered Rhodes in a restaurant in front of four people, and bad moments in major events with a large but diluted audience. Ultimately the audience decides what was a fine moment, and you don’t always get that feedback.

Thank you. Last word is yours.

The lock downs in France were somewhat hard on me, I made up for it with a strong diet of daily piano and composition. I have just recorded with Claude and Mats Gustafson. I have another record planned with Fabien Robbe. I’m 84 but my health isn’t too bad, all things considered. As I always say, love songs and death songs don’t interest me much. Everything’s been said about love and death, so I don’t think about them.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: François Tusques | Copyright: François Tusques

Very special thanks to Julien Palomo

François Tusques Facebook

Improvising Beings Bandcamp

SouffleContinu Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp

Marvelous! Absolutely terrific interview, Klemen, thanks! (And hello, Julien, thanks to you too for helping make this happen.) Only in the past couple decades did I come to appreciate that Tusques is a major artist—on a world level—and your interview helps put many details about his colleagues and his times in one place. I’m glad the wise William Parker has been hip to him—Tusques is a treasure!