Alas | Interview | ‘Pinta Tu Aldea’ – prog rock with avant tango influences

Alas was an extraordinary mid-1970s progressive rock group from Argentina. They are considered the first prog rock band with avant tango influences. The band released some of the most original material from the genre.

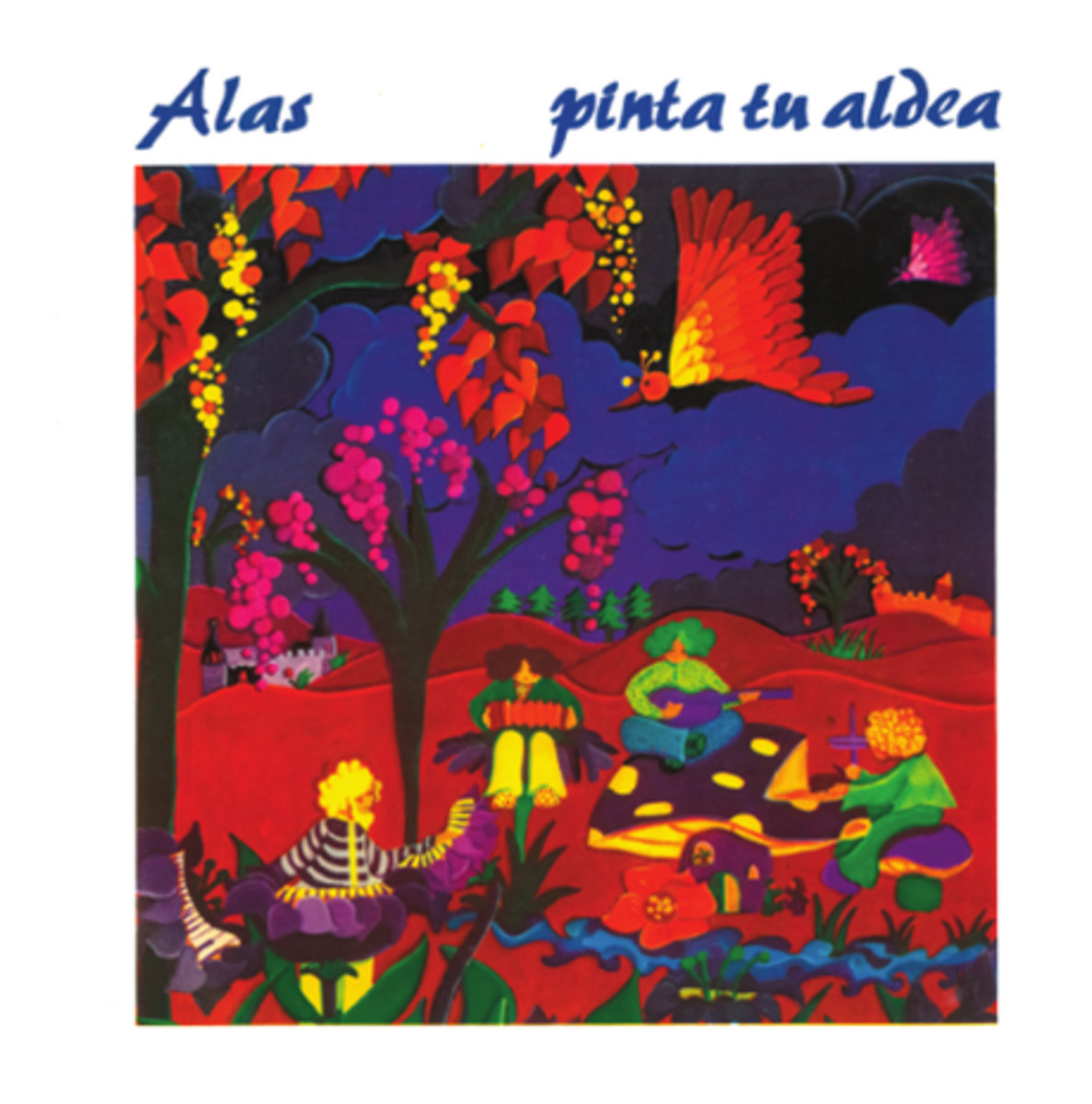

PQR-Disques plusqueréel just recently issued ‘Pinta Tu Aldea’, originally recorded in 1977, and formerly released by EMI in 1983. It’s the first official release of this one-of-a-kind gem in a strictly limited edition of 300 copies, with a newly designed (and band-approved) back cover.

Alas digress from their ELP-esque affinities which permeate their debut album, in quest for a unique sound that would blend for the first time the avant tango idiom of Piazzolla with the multilayered prog arrangements of Gustavo Moretto, with a helping hand from Carlos Riganti and Pedro Aznar. ‘Pinta Tu Aldea’ laid the very foundational building block of an eclectic sub-genre, namely, avant-tango/prog jazz and folk fusion. This has nothing to do with tango for purist tango lovers, obviously, but with a freeform adaptation of tango instrumentation and composition paths to the exigencies of to the exigencies of prog rock in conversation with jazz-fusion, folk and electronics, culminating in an expressionist landscape of unparalleled virtuosity, a bedazzling puzzle of motifs that might be rearranged ad infinitum in a maze of ever-shifting porous boundaries.

“We had to “play” in Spanish as well”

How did you first get interested in music and what can you say about growing up in Buenos Aires?

Gustavo Moretto: I had a wonderful upbringing as my father was, at one point, the most important Civil Engineer in the country and president of various international congresses of the same discipline. He wrote the standard book on Reinforced Concrete used in universities all over Latin America. My mother was a highly accomplished piano player and a pioneer composer/woman of contemporary 20th Century music. Both had studied in Argentina and had gained scholarships to study for four years at the Chicago State University at Urbana Champaign. Thanks to my mother’s talent, friendly intelligence and vision, our home became a sort of 19th Century Salon for much of the late 60’s and early 70’s. Our home attracted artists, musicians, architects, et cetera who came together for some of the most memorable evenings in my life. As a country, Argentina has always been a mixture of political tension and ethnic/socioeconomic disparity, influenced by a large influx of European immigrants and a multicultural fabric that has been an integral part of the country’s traditions.

Was it difficult for you to get new rock’n’roll records when you were very young?

Gustavo Moretto: My interest as a young musician was in the trumpet as an instrument, so the first record I bought was by Al Hirt. Interestingly, a wonderful Argentinean colleague of my mother’s (Francisco Kröpfl, born in Romania) protested my taste in music and said that Al Hirt’s music wasn’t really jazz. The next time I saw him, he lent me two albums by Clifford Brown (!). It was a huge leap for me, listening to that highly acclaimed musician. Since that moment I was hooked on jazz and jazz trumpet players. So, I wasn’t interested in rock’n’roll but rather in jazz and classical music. I was exposed through my mother to contemporary 20th century music. Finding records of contemporary releases of any kind in Argentina was almost impossible, but some would popup here and there.

Do you recall a moment when you knew that you wanted to become a musician?

Gustavo Moretto: I listened to music ever since I was inside my mother’s belly (practicing her piano), but I also became seriously interested in poetry since I was a ten-year old child. Throughout my teen years I pursued both writing and music. I became passionately interested in the trumpet when I was eight years old. Unfortunately, my parents refused to buy me one until I was fourteen (I will never forgive them for that). At fifteen I started taking formal lessons on trumpet but was still undecided when it came to a career in music. All the while I was playing piano informally with the very little training I had gotten from my mother (not her fault…). My decision to become a musician was made when I finished high-school and realized that music required an in-depth knowledge of theory and training. I studied for two years in an excellent preparatory course, eventually leading to a career in music at the Catholic University (the only institution that had a college-like career in the musical arts), but I never intended to enter college. So, I quit after those two years with a solid education in the basic elements of music theory, ear training and traditional harmony.

What were some of the early bands you were part of?

Gustavo Moretto: Playing trumpet in Argentina during the late 60’s as a young musician was a lonely business. Most of my generation during that period were interested in rock’n’roll or Argentinean folklore. The trumpet didn’t belong to those music styles. I joined a group called “Rhythm & Blues”. The music was closer to a jazzy blues than a rock style blues. The project was short-lived but interesting for my trumpet skills.

“During the first half of the 70’s (and beyond) Alma y Vida was the most popular band in Argentina”

Would you like to discuss the formation of Alma y Vida? Please tell us also about the album you were part of…

Gustavo Moretto: Alma y Vida originated as a backing band for a then famous commercial singer and film-maker, Leonardo Favio. The band was originally put together for that purpose by Carlos Mellino who would later become the singer for Alma y Vida. At one point Mr. Favio retired from his singing career leaving the musicians of the band without work. Since the group itself sounded great, the idea was born of creating an independent band with Carlos Mellino as the vocalist, since he was an outstanding singer himself. Bernardo Baraj, who played saxes and flute came up with the name of the group which in English translates into “With life and Soul”, a Spanish equivalent to Blood, Sweat & Tears. The only problem was that the trumpet player of the original band (Mario Salvador) was a classical-trained musician and would only work for paid performances, something a new band could not guarantee. As I mentioned before, there weren’t too many young trumpet players in Argentina at that time, so eventually they got my phone number, and I joined the band. I had no professional experience as a musician till then, but the band members encouraged me, and I worked with them during four very important years of my life. We recorded four albums where I composed part of the music (one of them became a hit: ‘Hoy Te Queremos Cantar’) , played piano and trumpet at the studio when recording the albums, and sang a few tunes. Most of Alma y Vida’s music was very sophisticated and reflected some influence by Chicago and Blood, Sweat & Tears. Starting with our very first album, Mellino wrote a series of great hits that defined the career of the band as a “song” band, rather than a progressive one. During the first half of the 70’s (and beyond) Alma y Vida was the most popular band in Argentina. Unfortunately, some of the most interesting music we created was eclipsed by those hits. Alma y Vida was never given due credit for the more progressive side of its music.

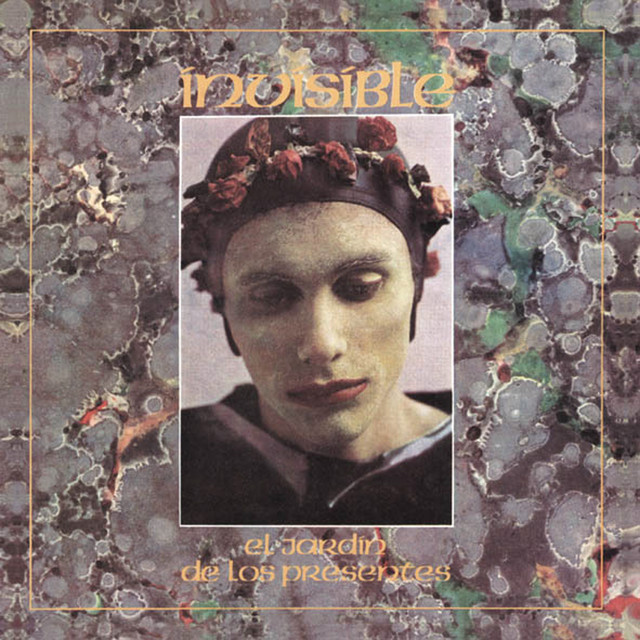

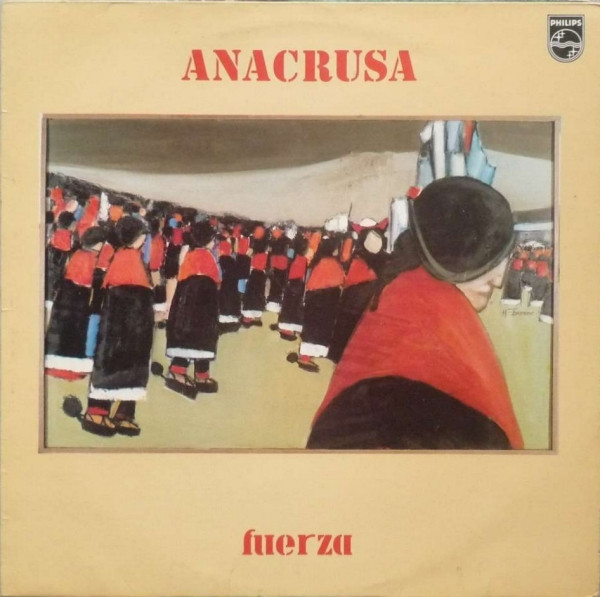

What about your participation in Invisible’s El jardin de lospresentes and in Anacrusa’s Fuerza?

Gustavo Moretto: I have been a fan of Luis Alberto Spinetta (“El Flaco Spinetta”) ever since his early band Almendra. Luis was a serious musician who took an early interest in my new group Alas. He was impressed with my composition skills and was very vocal in the media about it. Eventually, I received a phone call from him to add synthesizers to his album ‘El Jardin de los Presentes’, quite an honor for any musician at the time.

In 1979 I left Argentina because of the horrors of a Military dictatorship, during which some of the worst crimes against humanity were committed. I originally went to Paris where my wonderful sister Marcia Moretto (check the song ‘Marcia Baila’ by Rita Mitsuco in her memory) was living. I stayed in Paris for a month where José Luis Castiñeira de Dios was working with Anacruza. Jose Luis learned I was in Paris and he called me to participate in his album ‘Fuerza’.

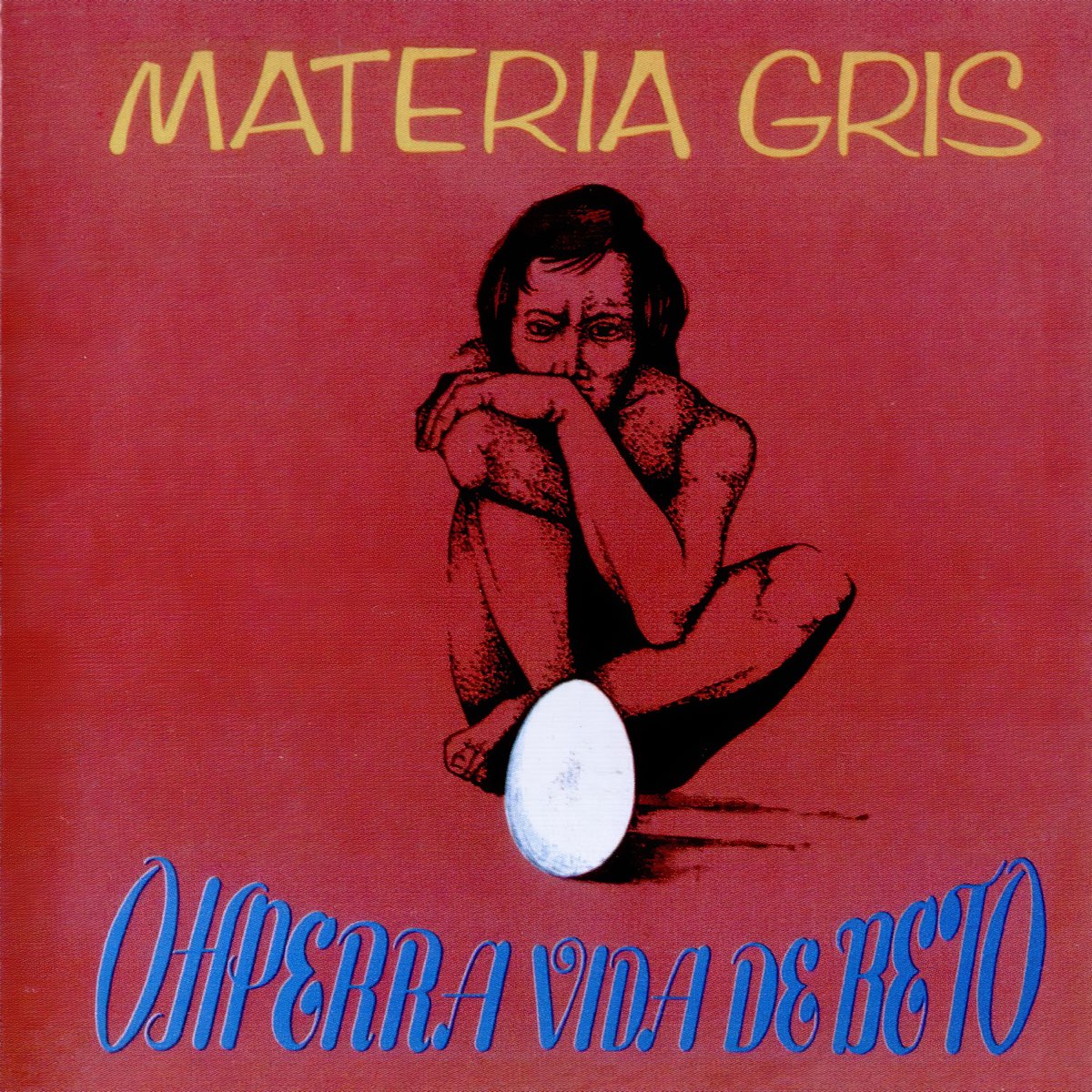

Can you also elaborate on the concept behind the short-lived Materia Gris?

Carlos Riganti: Materia Gris was an Argentine progressive rock band, with a strong vocal imprint derived from an early Beatles stage, which was later consolidated towards a Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young style. This first stage is clearly seen in the single ‘Carta Para Un Amigo’ that was released by EMI Odeon in 1970. The band played in local shows with a very good repercussion in the Argentine progressive rock circuit.

Many groups in Argentina started working on projects inspired by The Who’s opera ‘Tommy’. For two years we were preparing our opera ‘Ohperra Vida De Beto’ and we recorded it at EMI in 1972 with a console that had been brought from London and a 4-channel Studer recorder. The two guitarists of the band (Julio Presas and Edgardo Rapetti were studying sound engineering) and prepared the recording sessions to make the most of the possibilities of the 4 channels. The result is surprising.

The arrangements combine psychedelic rock moments with heavy rock passages, and vocal lyric passages with a melodic sound and excellent guitar arrangements. From the percussive side, it combined the strength of rock with passages in 6/8 characteristic of Argentine folk music.

Litto Nebbia and Bernardo Baraj collaborated on the album as guest musicians. When we presented our album in concert, Pelo magazine was the promoter of the national rock movement. They inform us that it was the first Argentine rock opera already recorded and presented live. It had a great impact on the rock circuit and is currently a highly appreciated cult vinyl release internationally. We then worked on another play ‘Pandemonium’ which was finished and performed live on various stages but was never recorded.

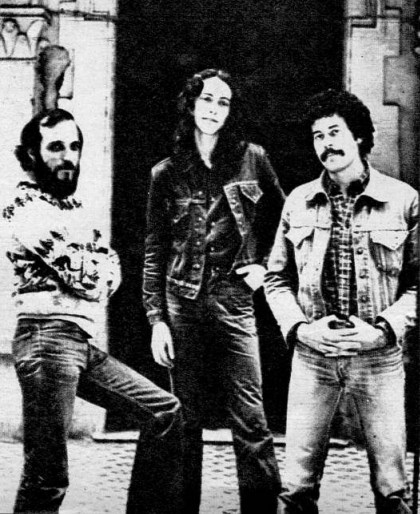

You gained a lot of experience with previous bands that can be heard on your exceptional playing in Alas. Can you elaborate on the formation of Alas?

Gustavo Moretto: Most of my experience as a trumpet player and pianist came from my being a member of Alma y Vida. In the music scene in Argentina, I was largely considered to be a trumpet player, not a pianist, and was called to play in studio gigs for other projects with that instrument. All of my piano playing was done in the studio for Alma y Vida. I had never played piano or keyboards in public or for other projects. Alma y Vida had a grueling schedule of performances where we mostly played those hits known to a broader audience. I had contributed with various compositions for that band that were of non-commercial orientation, and I had honed in some of my piano skills in those recordings. I became very interested in the composition aspect of music and felt somewhat frustrated by an ever-increasing pursuit of the business aspect of Alma y Vida. In 1974 I decided to leave that band and start a group where I would be the sole composer and music director. Alma y Vida was a sextet, so I wanted to create a trio. The advent of the synthesizer allowed a keyboard player to be the soloist and main instrument in the style of the rock guitar trios, such as Jimi Hendrix Experience and others. It was a risky move since I was leaving a very successful band and starting a brand new one with an instrument other than the trumpet.

For quite some time there was a lot of confusion in the music community by my so-called “change of skin” both as regards the instrument and the music itself. My first instrument was a Fender Rhodes and an Ampeg 300 bass amplifier (eventually we built the speakers ourselves). After thinking about possible bass players, I remembered Alex Zuker whom I had known from the music community. He agreed to be in a project with me, and we started getting together to play the music I had composed thus far. Alex was also skillful in bringing musical instruments from the US and so eventually my keyboard set-up was Fender Rhodes, Hammond M3, ARP 2600 and an ARP string ensemble. That would be the set-up for the rest of Alas history.

Next, we tried several drummers, none of whom we were happy with. At one point I remembered an excellent drummer I had heard playing in a band in my high school. I hadn’t seen him in many years but was able to contact him. When he came to the rehearsal there was an instant realization that he was the drummer we needed. We were very lucky… My compositions at that early time were very different from what would eventually be recorded in the first album. I will forever regret not having recorded that early material. People would have had a different version of Alas today.

How did you get signed to Odeon and what were the circumstances behind working on your 1976 debut release?

Gustavo Moretto: Once the trio was in good musical shape (approximately one year later) I still had a contract with RCA through Alma y Vida. I called a producer I knew from that company and suggested a trial recording session. In that session we recorded two of the early compositions. They gave us half an hour and we nailed it! Despite the recording success, RCA was not interested in the group, so we felt quite disappointed. I made up my mind that we were not going to ask any other company to have us in their catalogue. They would have to come to us. Not long afterwards a representative from Odeon came to our rehearsal with a proposal to join the record company. By then we had grown a bit arrogant and demanded to have a higher percentage of sales and to be able to negotiate our contract every year. We got it.

“The idea was to deviate as much as possible from the US based stylistic language”

Where did you record it and what can you tell us about the complex arrangement?

Gustavo Moretto: The first album has only two compositions of about seventeen minutes each. The idea of using the music language associated with tango was suggested to me by my dear sister Marcia Moretto. I will forever be thankful to her for inspiring me to follow that idea. The music of that first album was a departure from the music Alas were playing at the beginning. This “new music” was more ambitious and reflected more of my growth in my compositional vocabulary. While side A of the album had tango elements in it, side B used rural folklore as a musical reference. The idea was to deviate as much as possible from the US based stylistic language that was prevalent in Argentinian bands and to incorporate music that represented our own culture and roots. We used to say in interviews for the media that singing in Spanish was not enough: we had to “play” in Spanish as well. The composition on side A is called ‘Buenos Aires Solo es Piedra’ which translates into something like “Buenos Aires has become just stone”. There was a programmatic structure in this composition, suggesting Buenos Aires was destroyed by a war. In this composition, I used just about every stylistic element I was interested in at the time: progressive rock, tango, jazz, classical music, contemporary 20th century music, song form and improvisation. All parts were written-through, including basslines, except for much of the drum parts that were not part of the overall arrangement (for obvious reasons) or improvised parts. The beginning of the tune ‘Buenos Aires Solo es Piedra’ starts with a complex phrase in unison. The melody is based on a 12-tone row (where all 12 pitches in western music are used). This melody is repeated three more times with the same rhythmic structure, different arrangement, but every time being more tonal (“friendlier”) in character. I wanted to use gestures that evoked tango music. In the 70’s all musicians in Argentina were blown-away by the music of Astor Piazzolla, so I used his unique sound to represent the music of Buenos Aires. Most of the motivic ideas are based on a two sixteen note followed by an eighth note. This would be the basis for the musical development throughout the composition. After the triple presentation of the theme there is a development of the motive mentioned above until a sort of climax is reached. This is when the theme is heard a fourth time in a quite complex multi-rhythmic arrangement. With enough tension achieved, I moved to a very soft and melodic moment (always looking for contrasts). In this part I sang a rather melancholic song using plenty of intervallic fourths, which is not the most typical writing for vocal parts. The lyrics suggest a destroyed Buenos Aires where nothing but stones are left of the city. Once that idea is established, we move onto a collective improvisation in the style of 20th century classical music. These sounds initially are meant to generate a sense of complete dissolution of the musical structure. Yet, this moment slowly evolves into a great crescendo culminating in a brighter, more forward-moving music with the ever-present initial motive. After several changes that include a kind of crazy, distorted merry-go-round, the song I sang towards the beginning is heard again, this time played with the trumpet. The composition ends with a much faster rendition of the original theme and a typical cadence (sol-do) which we subsequently destroy by the wrong cadence (sol-re). There are quite a few moments of polyphonic (multilayered) writing in both compositions. Creating multilayered music was essential for the trio formation, as I wanted to create the illusion that there were more than three musicians on stage (a preoccupation I always had when composing for Alas). This multilayered texture required working on the independence between my two hands and my feet.

Did you do any touring to support the release?

Gustavo Moretto: I wished we had been in a country where such a logical sequence of events could have materialized. We were quite busy already when the first album was released, and the music had been part of our live performances for some time by then. Odeon did almost nothing to promote the album.

How would you describe the scene in Argentina back in the 70s for a rock band?

Gustavo Moretto: It was a wonderful period of great creativity. We, in Argentina, were highly inspired by what was happening world-wide with the progressive rock movement. The problem (and the blessing!) was that the country couldn’t afford to bring those great bands to our stadiums and theaters. That forced us to create a local progressive scene in Argentina that had no international competition for our audiences, but no international publicity either. There was a very enthusiastic public response for that kind of music and talent that became internationally recognized much later with the advent of the Internet era.

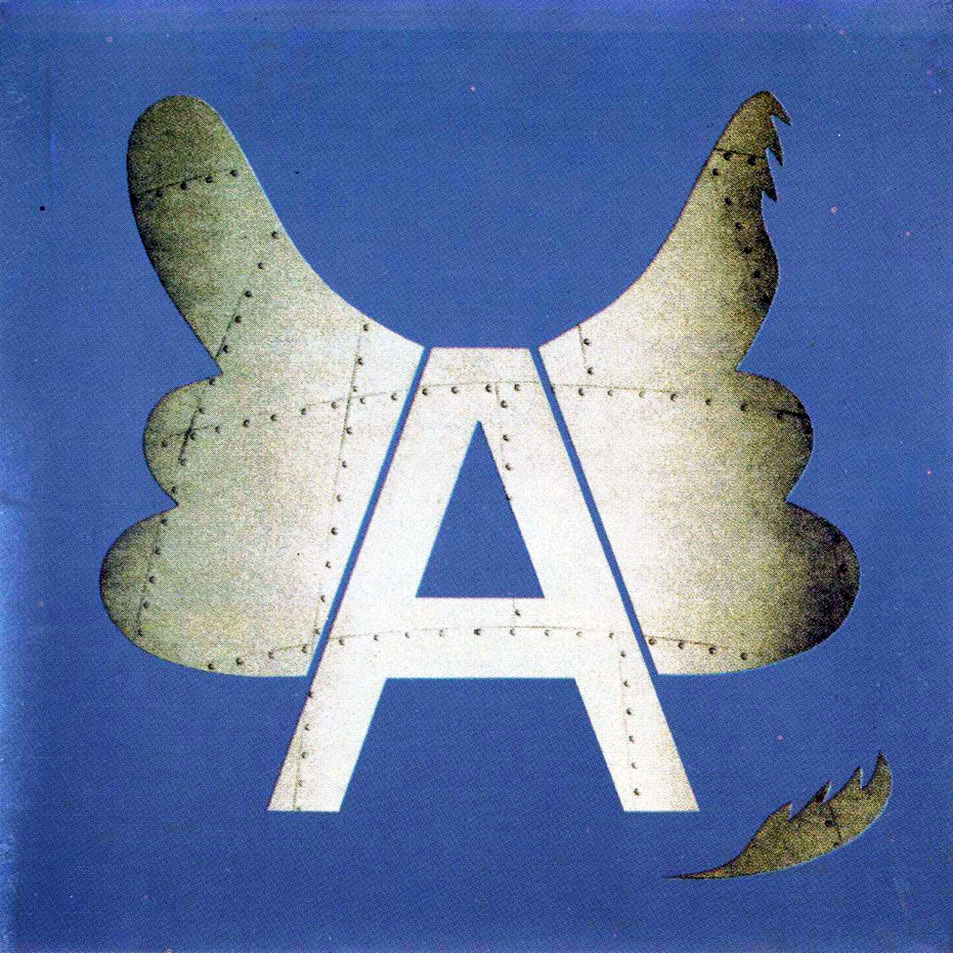

Your debut has a very striking image used for the cover. What can you say about it?

Gustavo Moretto: I came up with the name Alas because it had only four letters, in contrast to Alma y Vida. Usually, when giving a big concert in the city, it was covered with big posters in key areas. When I was with Alma y Vida the posters were big, but the letters were small, so I decided to have a short name for the group so that the letters would look much bigger.

Alas means “wings” in Spanish, and I understood the importance of attaching a logo to a project. The letter capital “A” lent itself perfectly to adding two wings on its sides. The most remarkable aspect of the cover was that it didn’t have any text or name in it! That meant that if you didn’t already know the band and/or the logo you had no reason to buy the album. We were quite arrogant…

Your second album, ‘Pinta tu aldea’ was originally recorded already in 1977 but was eventually released by EMI in 1983. What were the circumstances behind this delay?

Gustavo Moretto: We had a deadline for the use of the studio for our second album. Sadly, the internal war in Argentina was at its most vicious during that time. I decided not to get on a stage again while pretending that nothing was happening (you couldn’t speak-out against the military government at the concerts…). I told Carlos Riganti and Pedro Aznar that the project was over. But we did have by contract to record a second album and we wanted to comply. My sights were on leaving the country altogether and when the recording started, the band was no longer playing live.

The recording was completed, but I had already left the country before the album was mixed! Pedro and Carlos completed the mix but since the band no longer existed Odeon didn’t publish it. Most recording companies in Argentina also went through a very difficult financial crisis during that time and much of the progressive movement was coming to an end. This was the beginning of the eighties…

Eventually the lack of a healthy recording business in Argentina forced Odeon and other companies to re-issue old material and publish anything that had been left behind. This is the reason that the second album was published in 1983. Again, no promotion was made for the release of the album, and it was mostly consumed by our core audience.

Your sound changed quite a bit. What do you attribute to this change in sound and arrangements?

Gustavo Moretto: As I mentioned above, the whole of the Alas project was an outlet for expressing myself as a composer (in Alma y Vida almost all the musicians composed for the band). I wanted Alas’ music and arrangements (which are one and the same for me) to be my own artistic manifesto. Alas had three distinct periods, each with its own particular sound and ideas. Quite regretfully, the original material was never recorded. That material was very different from the music we recorded in the first album, and it marked a natural progression in my compositional objectives. By the time we recorded the second album I had moved past the concepts of the first one and was immersed in a completely different musical path. The incorporation of Pedro Aznar into the band allowed me to move much faster as a composer and to be more ambitious in what we could do as a band. Interestingly, despite this improvement, when the time came to record the second album, I didn’t have enough material for it. Worse: there was an entire long section (the middle part of ‘Silencios de Aguas Profundas’) that I was very unhappy with.

In hindsight, this situation was also a blessing in disguise. We recorded ‘A Quienes Sino’ and ‘Pinta tu Aldea’ which were already part of our live performances. We had been rehearsing the complete version of ‘Silencios de Aguas Profundas’ but when the time came to record it, I was very dissatisfied with the middle part of that composition. Given the incredible speed at which Pedro could learn new music, I was able to compose a new middle part for ‘Silencios de Aguas Profundas’ and another brand-new tune (‘La Caza del Mosquito’) in a matter of days. Unfortunately, it became impossible to teach that music to Carlos: it was too complex, and we had less than a week to record it. To illustrate this situation, I literally got on my knees on a Friday and prayed to come up with an idea for the middle of ‘Silencios’. I composed music that was extremely demanding that day, assuming Pedro knew how to play the guitar (!) I called him and asked him if he indeed played the guitar and he said yes. We got together the next Monday, taught him the guitar part and recorded it on Tuesday, the next day. His guitar playing was masterful! The best part of this situation was that I had complete freedom to compose whatever I wanted without limitations since the whole project was over by then. I felt free to experiment and, given the speed with which I had to compose, I had to abandon any inhibitions and push forward no matter what. In the studio there was a very old noisy electric fan which I used as a background sound for my piano solo in ‘Pinta tu Aldea’. I also tore several pieces of paper next to a microphone that had background noise, and played a few licks with my trumpet ala Miles Davis. It was a good lesson. For the introduction of ‘La Caza del Mosquito’ I had in mind a very talented teenager who played the flute part. Her name was Cecilia Tenconi.

What was the concept behind it? You married complex jazz fusion with tango influences and the end result is a completely unique record.

Gustavo Moretto: The second album was yet another jump in my compositional evolution. Each composition has its own conceptual raison d’être.

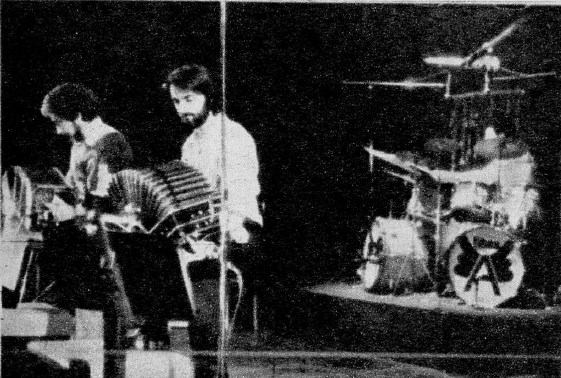

‘A Nuetros Amigos’ was composed as an opening for our concerts (especially for theaters, concert halls). My idea was to start a concert with such overwhelming energy and display of virtuosity as to “conquer” the audience from the very beginning. That gave us oxygen and trust from the public to follow-up with the rest of the concert, choosing whatever order in the musical program we wanted.

‘A Nuetros Amigos’ starts with a long digital-string introduction. The lights in the concert-hall would go off and the introduction began with the curtains still down. It was a long, rather tense moment because the audience had to wait to see us onstage. Yet the music was very calm, creating a bit of a contradictory set of emotions. By the time the strings would be coming to an end, the bass would start its restless pattern, and by the time the bass pattern was finished the curtains were up and the band would be visible on the stage and the very energetic music would start. It worked…

‘Pinta tu Aldea’ comes from a quote from Leo Tolstoy that said “If you want to be universal, start by painting your own village”. It starts with, again ,a twelve-tone bass-line that continues as a contrapuntal line throughout the theme. The theme itself has a rallentando part which is sometimes heard in traditional tango but that was very unusual for a rock band. This composition was the first that required a Bandoneon as a fixed part of the instrumentation. That made Alas a virtual quartet, rather than a trio, towards the end of the band’s career. We were blessed to include in those performances and the second album two of the most brilliant Bandoneon players in the world: Nestor Marconi and Daniel Binelli, both of whom went on to have extensive international careers.

Towards the end of the extensive “A” section there is a soli in unison that has been a challenge for musicians ever since we played it the first time. The “B” section is the piano solo with the above-mentioned old and noisy electric fan, the tearing of paper and the trumpet “comments” in the background. When the “A” section returns, there are two exceptional solos by Daniel Binelli and Pedro Aznar. The return of the theme starts with the difficult soli and ends with the rallentando.

‘La Caza Del Mosquito’ was a search to include humor in my compositions. It’s a fast and intricate theme that had melodic turns that were jumpy and unexpected. The meaning of the title translates into something like “The Mosquito Hunt”. At one point in the music there is a barely audible clap that represents the mosquito’s demise. The introduction with piano and flute was a short composition of mine in the style of 20th century music. At the very end the theme (and the flute/flutes) comes back a last time in a completely reharmonized and slow version.

Finally, ‘Silencios de Aguas Profundas’ came to me as an idea of reversing the fast-slow-fast structure I had used in other compositions. I wanted to create a slow-fast-slow structure and explore its possibilities. This is the composition where the middle (fast) section had become a problem for me. I hated what I had composed for it and had to change it only four days before we recorded it. Kudos for Pedro Aznar’s incredible ability to learn new music (and playing it with a guitar!)with such tremendous speed!

Who is behind the cover artwork for your second album?

Gustavo Moretto: Sorry, I can’t remember her name. She was a neighbor/artist of mine

Tell us more about the recording process, where did you record it and what are some of the strongest memories from the studio?

Gustavo Moretto: We were more than ready to record ‘A Nuestros Amigo’ and ‘Pinta tu Aldea’ because we had played them many times in live situations. I think it’s possible to hear that in the recording. In contrast to that, ‘La Caza del Mosquito’ and ‘Silencios de Aguas Profundas’ had not been played live and were composed just a few days before they were recorded. Of course, that created a different dynamic for those two tunes.

The strongest memory I have of the whole process was the fact that this recording was the end of our journey as a band and therefore I had the freedom to do whatever I wanted without thinking how it was going to affect our career.

One of the enduring moments during the recording of that album was when I asked for the studio lights to be turned off so that I could play the solo piano of ‘Pinta tu Aldea’ in almost complete darkness.

PQR-Disquesplusqueréel reissued ‘Pinta Tu Aldea’. Are you excited about it?

Gustavo Moretto: Very excited. Of the many reasons we’re happy to have a re-issue in vinyl is that none of us has an original cover that’s in any good shape. The most important fact without a doubt is that while we were making that music in the 70’s, we were blocked from any international exposure (Chile and Brazil being an exception). We were absolute fans of the progressive movement in Europe and didn’t know how we would compare against such giants! I thought we were just local heroes. This may be a chance to be paired with those great bands and take the heat!

How does it feel to hear your music back on vinyl after so many years?

Gustavo Moretto: It is definitively the real, authentic sound we always had in mind!

Would you mind talking also about your 2005 release, ‘MIMAME Bandoneón’?

Gustavo Moretto: ‘Mimame Bandoneon’ as a project would have to be counted as one of the biggest challenges of my life. The idea of a “return” of Alas was extremely risky. In the early 2000’s it couldn’t be based on synths, they were no longer fashionable then (today those synths came back big time…). That meant I had to reorchestrate everything for an acoustic band. First, I had to transcribe all the music from the album since I had never written complete scores in the 70’s and all I had were some sketches here and there. I decided to replace the synths with an electric guitar (my son, Martin Moretto) and a fixed, permanent bandoneon for every tune except ‘La Caza del Mosquito’. Perhaps the biggest challenge was for Carlos Riganti who had always been a very powerful drummer and now had to re-orchestrate his part to the level of an acoustic band. The idea came up by building a drum-set adding pots and pans, a reference to the fact that we were a band from the third world!

Amazingly, this drum set was featured as the “drum set of the month” in the international magazine Drum World.

The question was: would Buenos Aires think we were still that unique band they heard in the 70’s? The answer, thankfully, was a resounding yes. La Nacion, a major newspaper in Argentina, wrote an article whose headline said that Alas was the music of Buenos Aires. That was after I had been living in the US for 16 years!

Did you perform the material from this record often back in the late 70s?

Gustavo Moretto: Alas had already disbanded by the time we recorded the second album. We did play ‘A Nuestros Amigos’ and ‘Pintatu Aldea’ often before the recording. ‘La Caza del Mosquito’ and ‘Silencio de Aguas Profundas’ were never performed live.

Are there any other Argentinian bands that you enjoyed and found interesting back then?

Gustavo Moretto: Many: Bubu, Crucis, Spinetta, Arco Iris, Madre Atomica, et cetera.

Would you like to comment on your playing technique? Give us some insights on developing your technique.

Gustavo Moretto: I wish I could say something helpful about my playing technique. I had studied the piano, formally, for a total of three years. I did learn a lot by watching my mother play. The rest was mostly intuitive. I did play a couple of Chopin Etudes, two Preludes and Fugues by J. S. Bach and some Grieg. I used those over the years as a technical “tune up” when I played big concerts.

When did you decide to stop the band and what followed next?

Gustavo Moretto: I stopped the band in 1978 due to the coup d’état in Argentina. I left the country and embarked on studies in classical contemporary music at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, US.

One of the reasons I became a student was that I could not stay in the US unless I was a full-time student. Eventually I was awarded a full scholarship both at California State University at Berkeley and at Columbia University at New York. I chose the latter and graduated with a Doctorate in Composition from that university. I had some of my classical compositions performed in the US (New York, Boston and in different California University campuses) and one recorded by a San Francisco ensemble of contemporary music called Earplay. Ironically I continued composing in a more jazz-tango style, but the journey through classical music was worth the while.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band?

Gustavo Moretto: Definitely our highlight was when we played three large concerts with an arrangement I wrote for three bandoneons. It was the first of its kind in Argentina and the world, and an extraordinary experience that will live with me forever.

What occupied your life later on in the 80s onwards?

Gustavo Moretto: Composing contemporary 20th century music, organizing the return of Alas and several projects in New York, one of which was a septet that included young jazz musicians. There’s also an album which I didn’t publish for violin, guitar, piano and contrabass, again using a mixture of jazz, classical music and tango.

We toured with the second version of Alas and had the opportunity of playing in Brazil where once a concert had been cancelled by the government due to censorship. I became a full-time, tenured professor at City University of New York. Other projects like Morettrio are also worth mentioning. There’s a television performance of that band on YouTube.

What currently occupies your life?

Gustavo Moretto: I just recently moved back to Argentina after retiring from my professorship. At this moment we are working with a quartet with Carlos Riganti.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Gustavo Moretto: Thank you for your interest and your insight into our project! I guess there is some poetic justice in the fact that coming from a very distant place and from a very traumatic experience during Argentina’s civil war, almost half a century later we can be proud to be remembered for our contribution to the prog scene.

Klemen Breznikar

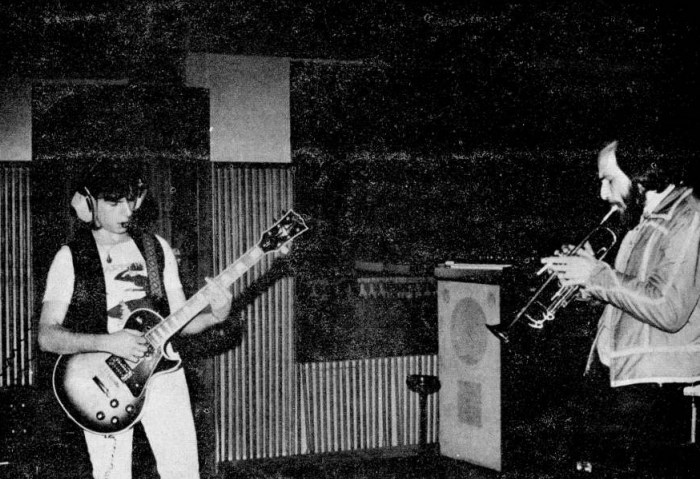

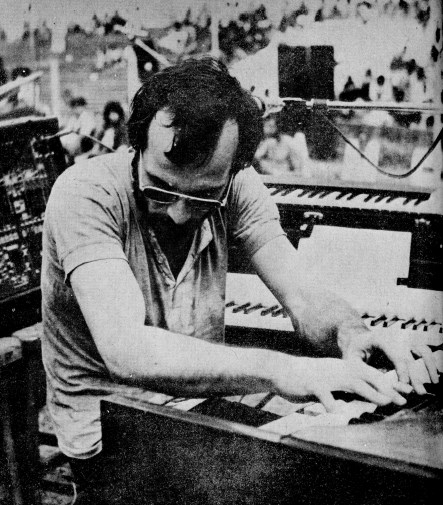

Headline photo: Alas and Astor Piazzolla

PQR-Disques plusqueréel Official Website / Facebook / Bandcamp / YouTube

Thank you Klemen for the band i don’t know. I like the south or central american music scene.

Thank you too for all the work you are doing !