Nick Toczek | Interview | “Living out of my hobbies”

Nick Toczek is a full-time professional writer and performer who works variously as a poet, music journalist, writer-in-schools, magician, puppeteer, radio presenter, political researcher and author, creative-writing tutor, rock lyricist and classical librettist, occasional stand-up comedian, and rock vocalist.

Born in Yorkshire in 1950, he’s been writing since he was a child, began getting his poetry published in his mid-teens, did his first public readings when he was nineteen, and had his first collection of poetry published when he was twenty-one. Since then, he’s done more than fifty thousand performances and presentations, has worked in more than forty countries, has published more than forty books.

“I wanted the luxury of making a living out of my hobbies”

You were raised in Bradford and went to study Industrial Metallurgy at Birmingham University (1968–71). There you began reading and publishing your poetry. How did you first get interested in literature and poetry?

Nick Toczek: I grew up in a house full of books. My mum was into literature and would, during the 1990s, run her own bookshop. From when I was very young family members would encourage me to write. I was always given diaries which I’d fill during January but then only add to when life became interesting or intense. Feeling guilty about neglecting these diaries, from about the age of 8 or 9, I decided to write on each page – not what I’d done, but what I thought. I’d write down any idea I’d had, sometimes a little story or poem, more often just a fragment of thought or even something memorable I’d read or heard. If I couldn’t think of anything new, I’d look back through previous days and pick out something on which I could do more work.

That set a style and method that I still follow. Thus: 1. Apart from when I’ve been unwell (rare) or been made to stop while on holiday, I’ve written every single day for the past sixty years. 2. I throw nothing away – even bad writing, because I can always return to it and find something to salvage or rework. Daily writing plus a low boredom threshold favours short pieces of writing so, though I have written longer pieces – several short novels (mostly unpublished) and a couple of political books, mostly I’ve produced poems, lyrics, and short pieces of prose.

Would you like to talk a bit about your background? What are some of the most important authors that shaped who you are today?

My dad was German Jewish but lost all his faith during WWII in which his father and brother were among more than forty members of his family to die in concentration camps and ghettos. As a refugee in Bradford after the war, he met and married my mum whose background was part-Irish, part-Scottish. Many of her family and friends would have nothing to do with her after the marriage. They, like many others in post-war Britain, disliked my dad either for being German or for being Jewish. That and the Irish/Scottish experiences of my mum’s family made me very aware of prejudice and injustice from an early age. I was the first of four children. I was rebellious and often in trouble throughout my school days, finally being expelled a few weeks before I was due to finish. By then, I’d already been accepted by Birmingham University. I’d originally wanted to study English Literature but didn’t qualify, then applied for Philosophy and Psychology, but failed again, so opted for Industrial Metallurgy and was accepted. I wanted to go to university because it gave me the freedom to be a writer, which was my main ambition. There was a thriving independent publishing scene in the UK, USA, and Europe during the 1960s and 70s, and I’d already started to have my work widely published in small press poetry magazines. I wanted to do more. I was heavily influenced by the Liverpool performer-poets (Brian Patten, Roger McGough, and Adrian Henri – who’d all later become friends of mine). I was also heavily into American Beat poetry, avidly reading Ferlinghetti, Ginsberg, Kerouac, and, later, the likes of Charles Bukowski, William Wantling, Kenneth Patchen, and Richard Brautigan. A big influence here was a Bradford writer who was linked with many of the writers I’ve just named. He was Jeff Nuttall who became a good friend and mentor to me.

“Meeting and working with others is the key to all successes”

In 1977 you founded your poetry magazine ‘The Little Word Machine’. How did that come about?

Wrong. I founded ‘The Little Word Machine’ in 1972 and produced a dozen issues (as both publisher and editor) before it folded in 1979 because my distributor suddenly went bankrupt and I lost everything – thousands of copies, all my sales, all my income, the money to pay the printer, etc. and ended up with the debts. It was a bad ending to what had, until then, been mostly amazingly good. Let me go back to 1969, I’d done my first poetry reading (a terrifying experience) in the main hall of the students’ union building at Birmingham University. A fellow student called John Akeroyd asked me if I’d like to start a university poetry magazine with him. We duly launched ‘Black Columbus’ a month later. This ran for half a dozen issues (one each term) and led to us forming a poetry reading group called Black Columbus Poets. I was performing and publishing! More importantly, I was meeting others and beginning to network.

Meeting and working with others is the key to all successes. My next influential encounter was at the end of one of these early readings in a Birmingham pub. I was approached by a Scottish poet called J.C.R. Green. His father, who’d been a publisher, had recently died and he’d inherited printing equipment. He wanted to launch a poetry press to be called Aquila. Would I and Keith Wilson (one of my fellow readers that night) each send him a manuscript? He wanted to start by producing a run of ten pamphlets. This he duly did in 1972. Among them were Keith’s and my first collections. Mine, ‘Because The Evenings’, began a ten-year close working relationship with Jim Green who published half a dozen more of my books as well as printed all the early issues of ‘The Little Word Machine’ and was hugely helpful with contacts, distribution, and promotion. In truth, Jim turned me from a keen amateur into a professional and nationally-known writer. Though we’ve now lost contact, we remained good friends for many years after that. You never achieve success on your own. It takes the faith and friendship of others.

A spin-off from ‘Little Word Machine’ came in 1977 when, via its imprint, LWM Publications, I brought out an influential book, ‘Melanthika: An Anthology of Pan-Caribbean Writing’. I co-edited this substantial anthology with the St. Vincent writer, Philip Nanton, and the Birmingham poet, Yann Lovelock. It was the first substantial British anthology of Caribbean literature and gave many people in the UK an introduction to black literature from established figures like Derek Walcott to newcomers like Linton Kwesi Johnson.

At the time you also already published a few books and pamphlets. Can you name a few and share a few words about them?

My second collection (also from Aquila) was a 1973 pamphlet called ‘The Book of Numbers’. This got some excellent reviews, sold well, got published in several editions, got me many more readings, festival appearances, interviews, etc. It and the success of ‘The Little Word Machine’ which soon had a print-run of over a thousand – very good for a poetry mag – really boosted my growing career as a writer-performer. Jim Green’s ten pamphlets included one by a well-known poet called Martin Booth who, on Jim’s advice, sent me some poems, two of which I included in the first edition of ‘The Little Word Machine’, along with a couple of Jim’s poems. Martin was researching the notorious British Satanist, Aleister Crowley. Jim got Martin to send me some unpublished poems by Crowley which featured in a later edition of the magazine and drew many new readers. Meanwhile, Martin, who ran Sceptre Press, took a poem of mine, ‘Evensong’ as a slim limited edition publication. That’s how networking – pre-Internet – played a central and mutually beneficial role for all of us. By choosing to work with writers you liked and respected as poets, you could help one another.

I’d been writing some very short humorous poems for a leading national weekly newspaper, ‘The Sunday Times’. They paid for them if they used them. This was my first paid work as a poet. I was still at school when the one first got accepted. They then began producing annual collections of the best of these. I had poems in the first two books and was paid again! Then there was a programme on national TV featuring some of them, including one of mine. I was paid again! Each payment was bigger. I began to believe that there was a living to be made. These poems were also really popular in my readings. My next two collections from Aquila ‘Malignant Humour’ (1974) and ‘God Shave The Queen’ (1975) brought together all of these short funny poems. That same year, Aquila published my novella ‘Autobiography of a Friend’. I was learning to write in different styles. To succeed as a full-time professional writer, I’d need this ability. Being a writer-performer is a perilous career… as Covid has shown us all. I wanted the luxury of making a living out of my hobbies – writing and performing. I’d need to be flexible and adaptable.

How did the Moseley Community Arts Festival come to life?

In 1974, I was living in Moseley, Birmingham. Known as ‘The Village’, it was home to many musicians, writers, and artists and so was the perfect place to start a festival. I’d been organising poetry and music events when I was approached by two local residents, writer John Dalton and musician Tom Sorohan. They’d had the idea for the festival and wanted me to work with them. Weeks later, we actually attended the national meeting at which it was decided to call events like ours ‘community arts’ – a new concept in creating truly accessible and inclusive cultural events. That summer, ours was the second British community arts festival, coming a fortnight after another such venture in nearby Tamworth. We ran 21 events on a budget of £300. It was so successful that we did a much larger one the following year, after which John and Tom moved on to other ventures which I went on to be director of the next two festivals, bowing out when I moved back to my hometown of Bradford in the summer of 1977. Moseley Community Arts Festival and its spin-off, Moseley Folk Festival have remained established annual events ever since.

When did you form The Stereo Graffiti Show and can you elaborate on who else was part of it?

My partner in the 1970s was the singer-songwriter, Kay Russell. In the early 1970s, we toured the UK as a poetry and music duo. By 1974, we’d started working with other performers. In 1975, we began using the name Stereo Graffiti (stereo being the music, graffiti being the words). We added the poet John Row from Ipswich (having met him at Edinburgh Fringe Festival), and two Birmingham-based musicians, singer-songwriter Jim Cleary and bassist Ron Bates. After Jim left, we had a series of singer-songwriters – Frank Crow, Francis Mallon, and Chris Rust – with one or two others guesting briefly, including famed Birmingham bassist Alec Angel. We toured heavily throughout the UK, doing mostly pubs, arts centres, colleges, and festivals, only disbanding in 1977 when Kay and I moved to Bradford.

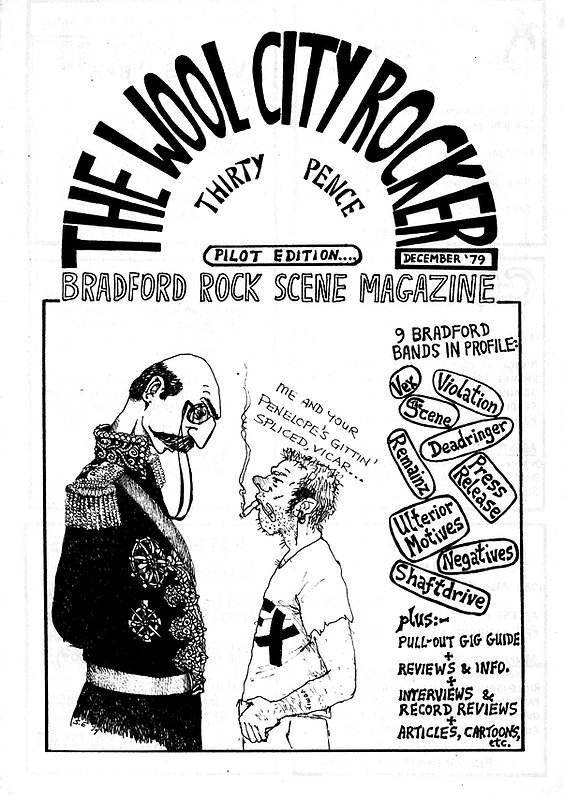

In 1977 you moved back to your hometown. There you founded seminal music fanzine ‘The Wool City Rocker’. Tell us about ‘The Wool City Rocker’; did you do any interviews with bands? What kind of stuff did you cover and how many volumes were pressed?

I’d been collecting punk fanzines, most of which were based in London or Birmingham. I wanted to start a northern fanzine that covered the emerging punk and indie scene but also dealt with other bands on what was a very active pub and club live music scene. Kay and I were on the verge of splitting up in December 1979 when we jointly edited and published the pilot issue of ‘The Wool City Rocker’ (Bradford having been the centre of the British woolen industry for a hundred years until it went into sharp decline in the 1960s and 1970s). On Christmas Day 1979, I met Gaynor at a party. We married in 1984 and are still together today.

From issue 2 until it folded after issue 14 in summer 1981, I wrote, edited, designed, published, and distributed every issue. In that time, it went from a Bradford to a West Yorkshire to a northern magazine made popular by its (pre-internet) gig guide and the free flexi-discs with several of the later editions, and circulation went from a few hundred copies of the first issue to several thousand, although, at 30p per copy, it never earned me money… but that was never the aim.

“Poetry sits mid-way between prose and music”

Would it be possible to draw parallels between poetry and music?

Since the 1960s, I’ve been heavily into rock, blues, and folk lyrics. There’s natural poetry in many early blues recordings and I was a fan. I got to see Bukka White, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Champion Jack Dupree and Willie Dixon live on stage while I was in Birmingham. I loved blues-influenced bands like The Animals, The Downliners Sect, The Pretty Things, Them, and The Rolling Stones. Obviously, Bob Dylan had a huge poetic influence, as did Leonard Cohen and John Prine. I could endlessly list other great lyricists. Poetry sits mid-way between prose and music. I use rhyme and rhythm extensively in my poetry and often write with music playing in the background or think up lines for poems while I’m driving and listening to music.

What are some of the inspirations for the poems? How do you usually approach writing? Do you have any special process or is it more a spontaneous affair?

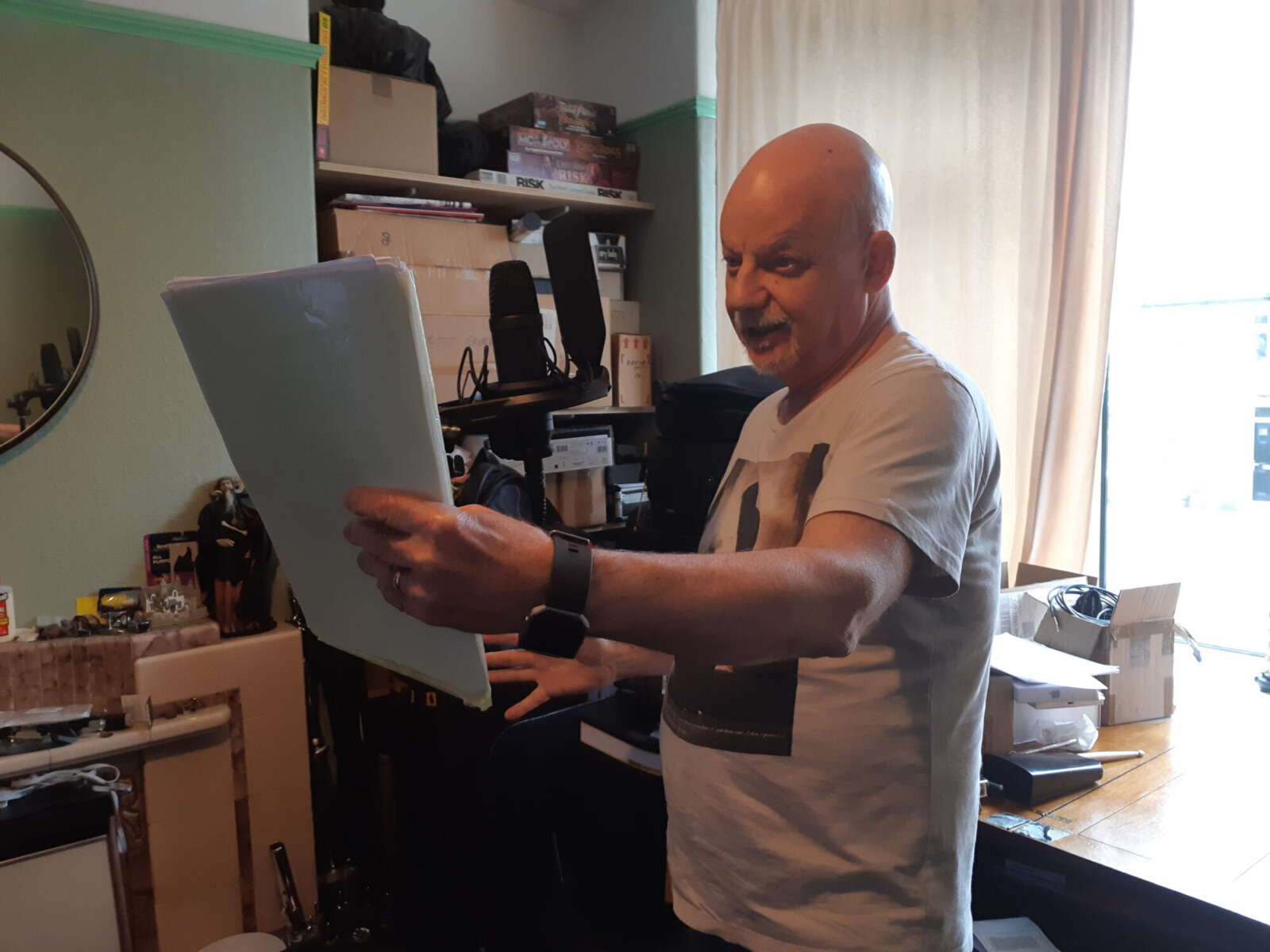

I write every day because it’s my job. If I was a plumber, I’d do plumbing every day. I’m not, I’m a writer, so that’s what I do. And, if I was an athlete or any kind of sportsman, I’d have to keep fit and have an exercise routine. That’s exactly what daily writing is to me. It keeps me writing-fit. I don’t necessarily write great things every day, but the process of keeping at it means that I stay open to all sources of inspiration and alive to processing and reworking my ideas quickly and effectively. Most of all though, I still love sitting down to write. I look forward to it every day. It always was and still is my favourite hobby. And there’s always the excitement of discovery because the first rule of good writing is that you must emerge from the whole process having learned something. If you’re not wiser for having written something, then it’s vain and arrogant to expect anyone else to benefit from it. Lastly, let me say that I still push myself to improve. From mid-March 2020 to mid-March 2021, I wrote and posted on Facebook sites one pandemic poem per day. The first book of these ‘Corona Diary’ came out a few months ago. The second ‘The Year The World Stood Still’ will follow in July, with the third, as yet untitled, due in early autumn. I do a daily walk (to satisfy my boss… my Fitbit) and have a new phone with a great camera, so I’ve been taking photos and using them as inspiration for a new series of poems which will either become a book or an online download, or both. These, meanwhile, are also going up on Facebook and provide me with material to read in the zoom gigs I’m regularly doing and in some of the live gigs which I’m slowly (and carefully) getting back into.

What led you to start your own band, Ulterior Motives?

Having seen loads of punk gigs before leaving Birmingham (The Clash at Barbarellas in 1976 and, in 1977 The Ramones with Talking Heads, The Adverts with Steel Pulse, The Prefects with The Slits, The Vibrators, Blondie with Television, etc.), Kay and I (her on guitar and vocals, me on percussion and vocals, plus a drum machine we’d used in Stereo Graffiti) wrote punk songs and began supporting local punk bands. By the end of summer 1977, we’d added Rick Green on bass. These were great times. Gigs were easy to find and our confidence in success was high.

“I was and still am an anarchist”

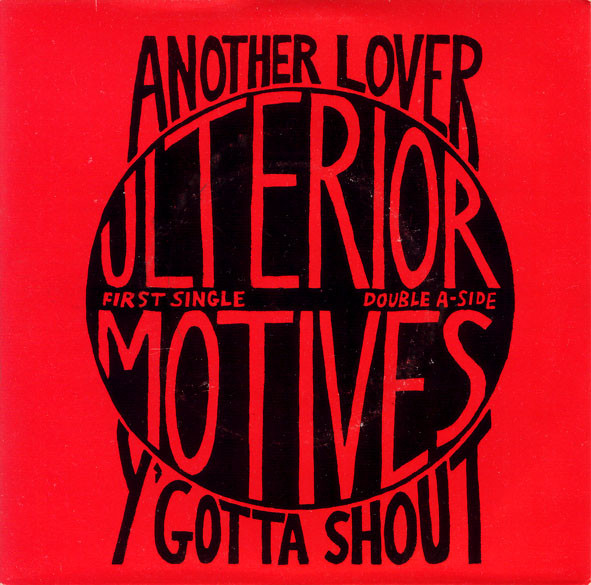

You released a single, ‘Another Lover / Y’Gotta Shout’ in 1979. What can you say about the band? Did you often perform?

Understand that trying to make a living as a writer isn’t easy. For the first forty-five years of my career (until around 2014) I was constantly in debt and managing bank overdrafts. I was and still am an anarchist. I never sought wealth. So luck and useful contacts were all-important. I had a small but very reliable p.a. system which I’d bought for Stereo Graffiti. I got on well with the people who ran Yorkshire Arts Association. They owned a small 4-track studio and rehearsal studio in Bradford. In exchange for leaving our guitar amps, p.a. and drum machine there for others to use, we got free use of the rehearsal space whenever we needed it, stored our gear there and, best of all, got very cheap use of the recording facilities, complete with the services of well-experienced sound engineers. It was perfect. All my life I’ve hated money and so pathways that freed me from dependence on it were truly liberating.

We gigged regularly around West Yorkshire and built a loyal fan base. Because I was a rock journalist and because we were setting up a fanzine, Red Rhino, an international indie record distribution service based in York, was more than happy to distribute both our single and a few hundred copies of each issue of ‘The Wool City Rocker’. What’s more, Tony K who ran Red Rhino, liked my attitude and so always paid me in advance for anything he distributed. Indeed, when I later (in 1986) released my 12-inch EP ‘More To Hate… Than Meets The Eye’, he financed the whole of the pressing costs and took on the distribution.

Kay left the band at the start of 1980 and, with Rick Green and a constantly changing line-up of other musicians and co-singers, I kept Ulterior Motives going until 1982. We recorded more material in various studios but released nothing more. However, a few tracks appeared on sampler albums over the years, then, in 1987, Bluurg Records run by Dick Bluurg (frontman of The Subhumans, Culture Shock, and Citizen Fish) released ‘InTOCZEKated’, an 11-track vinyl album of my musical recordings with a variety of bands.

This included several tracks by Ulterior Motives. More recently (2007) Mutiny 2000 Records released ‘Totally InTOCZEKated’, a 25-track CD that includes eight Ulterior Motives tracks. I still love this varied album and think of it as a great introduction to my musical recordings. It’s available from my website, as are my more recent recordings of both poetry and music, along with many of my books.

You also collaborated with quite a few bands.

Again, many of my collaborations have come from networking. Once I started running punk and indie clubs, many of the bands became friends. Often, they’d stay overnight at my house. We’d party and chat and share ideas. Some of these turned into plans to either gig together or record together. I toured Holland with Apocalypse Choir (from Hebden Bridge in Yorkshire) and with To Be Continued… (from Leeds they later became The Dead Vaynes and then The Vaynes). ‘Totally InTOCZEKated’ includes recordings with both of these bands and with Scarborough skinhead band The Burial, Bradford ska band Spectre, US punks Toxic Reasons (with Derek from Peter and the Test Tube Babies and Mick from The Fits), Darlington punk band Dan, and wonderful Stiff Records star Wreckless Eric with whom I recorded in France.

“I made attending punks and skins remove any racist badges”

Then the 1980s arrived! You ran a series of weekly punk and indie gigs. What bands do you recall the most?

I started at The Funhouse in Keighley with weekly Monday night gigs. It was a rough town and running those gigs was a steep learning curve. The first night, on 22 April 1982, was headlined by a skinhead band called The Business. Nine months earlier, on 3 July, the Southall Riots began in London when three skinhead bands – The 4 Skins, Last Resort, and The Business – played the Hambrough Tavern, a pub in the centre of an Asian area. Fights between local Asians and gangs of racist skinheads on that Friday night led to Asian youths attacking the pub and burning it down before the gig had finished. The ensuing riot lasted all weekend and spread throughout that part of London. The band had been unable to gig since then. I got them to reform for this gig on the condition that they’d help ensure there was no racism. I made attending punks and skins remove any racist badges and made it clear I’d stop the gig if there was any racist chanting or Sieg Heiling. It worked. The band did more gigs for me. They were grateful and, two years later, skinhead label Syndicate Records (run by Business bassist, Mark Brennan and the band’s manager, Lol Pryor, paid for me to record with anti-racist skinheads, The Burial, and then included one of our tracks (as Nick Toczek’s Britanarchists) on the popular 1982 skinhead compilation, ‘The Oi! Of Sex’.

A week later, the second gig at The Funhouse featured three acts from Leeds – The Sisters of Mercy, The March Violets, and skinhead ranting poet Seething Wells (who later became a lodger in my house and someone with whom I toured the UK and Europe). All three acts went on to become successful. The Sisters and I made plans to record together but both of us became so busy that it never happened.

Over the next few years, I ran weekly gigs. Soon I moved from Keighley to the larger urban centres of Bradford and Leeds. By putting on a gig in one city and then repeating it the next night in the other city, I could offer bands two gigs without having to do too much extra work. Doing even more weekly gigs didn’t involve too much extra work, so I ended up doing as many as five gigs a week. I used numerous venues, designed all my own flyers and posters, and built a reliable core audience. Punk and skinhead gigs drew reliable crowds. Indie and other gigs proved less reliable. However, I was doing mostly Monday to Wednesday gigs, when venues were at their quietest. The management of each venue was therefore more than happy for me to bring in plenty of drinkers on what would otherwise be dead nights.

It’s hard to choose the most memorable bands, but here’s a rather random handful. I’m proud to have put on Sonic Youth who went on not only to global fame but also to spearhead the rise of grunge and a slew of exciting bands including Nirvana. Likewise, I put on a couple of gigs featuring Bad Brains who stayed on as my house guests for several days. I very memorably put on a series of King Kurt gigs, the first two of which were the messiest and craziest of all my promotions. I got on really well with The Fall when they did two gigs for me. Mark E Smith told me I was the best promoter he’d ever worked with. I lost a hundred pounds over the two nights and the band gave me that money back. Also, as he was leaving, Mark gave me an extra fifteen pounds, saying “Get yourself a few pints and a curry with this.” Your job as a promoter is to please (a) the audience, (b) the performers, and (c) the venue and its staff. Often you’re exhausted and even disappointed, but if everyone else is pleased, then you’ve done your job, regardless of how you feel. Yet, if you do feel great afterwards, as I did that night, then that’s a welcome and encouraging bonus.

In truth, what’s best about being a promoter is not the famous bands. It’s how much you help and encourage new and smaller bands. They and your regular audience members will often remember you fondly forever.

What about co-organising events with Wild Willi Beckett?

Willi had long been a friend. We were both Bradford ranting/performance poets. In the autumn of 1986, Gaynor was heavily pregnant with our first child, Becci. I gave up promoting band gigs in Leeds and Bradford because she needed me around more. However, I still needed work. Alternative cabaret was just beginning to take off in a few clubs around London, I’d performed at a few of them and was keen to start something similar in the north. Doing so in Bradford meant I could still be home easily. Willi didn’t drive, so Bradford suited him too. Live music was not what it had been in the early 1980s, so venues needed something else. Comedians and other cabaret acts were cheaper to book and keen to get work. A guy in Manchester had just launched a similar club when Willi and I began ours in a Bradford pub, The Spotted House, in late September 1986. The two of us were well-known local figures, so getting the word round and bringing in an audience wasn’t difficult. We shared compering duties, had a DJ to play before between and after all the acts. The first night featured another Bradford poet, Little Brother, Support acts were Dooj, a singer-songwriter for Halifax, and an utterly eccentric theatrical guy from Bradford called Al Beach. The next four shows featured northern poets, singer-songwriters, a comedy juggler, and a ventriloquist. By November, things were going well enough for us to start bringing in acts from around the country. Tymon Dogg had been on an album by The Clash, Tohu Bohu was a great Cajun band I’d seen at a festival, Skint Video and Henry Normal were both fast-rising stars of the new comedy scene. The opening months of 1987 saw us adding bands, varying the music more (with blues, rock, classical music, and reggae acts), booking more comedians, and adding a few experimental performers. We were also booking really good comedians and, by May, really famous poets, including John Cooper Clarke and Benjamin Zephaniah.

Throughout 1987, the whole project became a huge success. In June we also ran a big Writers’ Festival and, in September, were employed by Bradford Festival to run a week of nightly alternative cabaret shows in The Alhambra, the city’s main venue. We survived some controversy when two acts caused offense but otherwise went from strength to strength, trying out more than a dozen other venues over the next few years. Willi left Bradford around 1992 but I carried on with weekly shows through the mid-nineties, and then intermittently until giving up completely in 2000 when other projects meant I didn’t have the time to continue. I’m a great believer in moving on once the challenge in any project ceases to excite you. I loved alternative cabaret, but too many of the acts were becoming mainstream and the whole thing was turning into big business. I wanted none of that!

You became a very well known author of children’s poetry. Where do you get inspiration to write for children?

In the early winter of 1995, a major UK publisher, Macmillan, brought out ‘Dragons!’ My first full collection of poems for children. For two years in the early 1990s, I’d been resident writer and storyteller at Eureka!, the museum for children in Halifax. My brief there had been to tell stories about dragons. Rather than use existing stories, I’d been making up my own stories and poems. By 1995, I had sufficient dragon poetry for this book. All my previous books had been with small publishers who sold a few hundred copies. Macmillan printed ten thousand copies and then the same again for a second edition a few months later. Over the next ten years, Macmillan published more than ten of my books. Working with them led to other books of mine being published by other major presses (Hodder, LDA, Caboodle, Routledge, etc.) which is why I’ve now sold almost a million copies of my books… a fact that still astonishes me as it’s way beyond anything I ever imagined I’d achieve.

How are you coping with the pandemic? You visited thousands of schools, but that’s probably on halt right now?

Emotionally, the pandemic’s been tough for me, as it has been for all of us. However, I’ve pushed myself to stay active and organised. As well as three vinyl albums and a CD album, all with music, I’ve also brought out two books and have several others on the way, all since the start of the pandemic in early 2020. Oh, and I made a short film, ‘Tvins’, about my father coming to Britain as a refugee. From mid-March 2020 to mid-March 2021, I wrote a pandemic poem every day, posting it on a couple of Facebook pages. With other poems which I’ve also written, that year alone saw me finish more than 400 poems and lyrics. I’ve also kept doing music journalism (I’m a columnist, reviewer, and interviewer for the UK music magazine ‘RnR’). Before the pandemic, I was working as a visiting writer in schools throughout the UK and visiting schools in up to ten countries a year. I’ve continued doing virtual school visits (via Zoom, Webex, Skype, and Teams), but on a much-reduced scale. I’ve also been doing loads of virtual poetry performances for adults, often with other poets, on both Zoom and Facebook. In May 2021, I did my first live gig (with and for adults) out in the open air on Baildon Moor. And, in June, my first family festival, doing a half-hour show (of poetry, puppetry and magic – I’m also a professional magician and puppeteer) in Selby Abbey to a live audience of around a hundred in the abbey, with loads more watching me perform on a huge screen outside the building and many more watching via a live feed on Facebook. So, while the pandemic mutates into new variants which try to outwit our vaccines, I’m keen to try out whatever pale imitations of pre-pandemic ‘normal’ come my way.

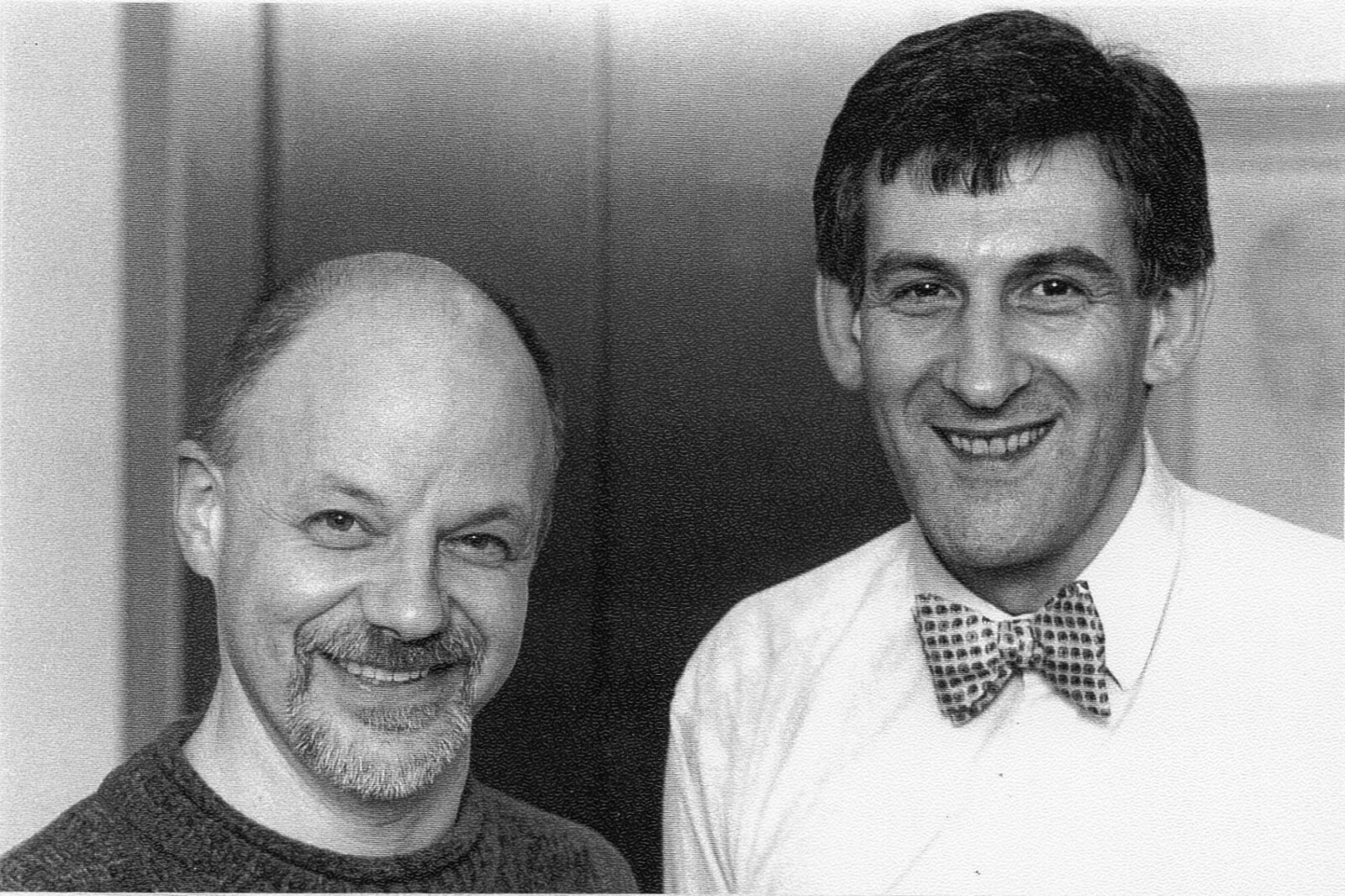

How did your collaboration with Malcolm Singer start?

Malcolm is a classical composer and conductor who, around 2001, came across a copy of my first Macmillan book, ‘Dragons!’ At the time, he was Head of Music at the prestigious Yehudi Menuhin School of Music and also worked at the equally important Guildhall School of Music. He loved the rhymes and rhythms in these poems and contacted me to ask if he could set them to music. I was delighted and flattered. It was a world away from what I was doing, so I jumped at the idea. We co-created our ‘Dragons Cantata’ which debuted in London’s Albert Hall with a choir of hundreds (including our young son, Matthew) and full orchestra. It’s since been widely performed, extended into a full musical, and published as such. Meanwhile, the publishers asked me to write a pantomime – ‘Sleeping Beauty’s Dream’ – which I did and which they also published. This has been widely performed too although, strangely, no one’s ever asked me to attend, so I’ve never seen a performance! One of my other books published by Macmillan was a collection of my football poems called ‘Kick It!’ Malcolm and I then co-operated in the creation of a football cantata called ‘Perfect Pitch’. This also had a London premiere followed by other performances. Post pandemic, further performances of both works are in the pipeline. Our most recent work has been a political opera based on Guantanamo Bay. It’s called ‘The Jailer’s Tale’. Dark and violent, it too had a London debut. You can find some cool extracts from it on the internet. After having taken a break from collaborating, Malcolm and I have just got back in touch and are discussing future possibilities.

Ok, now back to your current music involvement. I’m listening to your latest LP, ‘Walking The Tightrope’. What’s the story behind it?

My website is, appropriately, designed for me by Matt Webster. He’s been a drummer in many bands since the early days of punk and we’ve been friends for decades. He drummed in Willi Beckett’s post-Psycho Surgeons band, The Psurgeons, who were in the process of recording an album when Willi sadly died of cancer in March 2007 – we and others worked together on his posthumous single ‘Kingdom Come, Bring It On!’ which was pressed in transparent green vinyl, containing his cremated ashes. Together, Matt and I then compiled and released an album of songs by Bradford’s seminal punk band, The Negativz. Matt (working with Gary Cavanagh) has been responsible for ‘Bradford’s Noise of The Valleys’, an ongoing series of books and CDs charting the entire history of music in and around Bradford. I’ve written reviews of these and helped out with information. In 2007, Matt released my retrospective CD album, ‘Totally InTOCZEKated’, on his label, Mutiny 2000 Records. In 2018, his label released ‘Dealing With The Darkness’, my 2 CD spoken word album. While we were working on that, he suggested that we might cooperate on an album of my spoken word stories and poems set to music. That’s when I discovered that he was a brilliant multi-instrumentalist and producer. I’d no idea how good he was until we began work on this project. Matt had returned to playing and recording music after a nine year gap due to illness and had recently begun creating his own music under the name Signia Alpha.

Suddenly, here was this great bass player, guitarist, keyboard player, and – of course – drummer laying down track after track and patiently encouraging me to add my spoken-word pieces. The result – with contributions from half a dozen other musicians who were friends of Matt plus my poet-rapper friend Dee Bo General – was ‘Shooting The Messenger’, a 17-track CD album released by Mutiny 2000 Records in early 2020. Later that year, Matt picked out twelve of those tracks, remixed most of them, and released them on his label, under the same title, but on 12-inch coloured vinyl. Matt’s an unstoppable hive of activity. Just six months later came our follow-up album, ‘Walking The Tightrope’ also on 12-inch coloured vinyl, featuring eleven brand new tracks with contributions from the same collective plus a couple of newcomers, including Paul Gray (of Eddie and The Hot Rods, UFO, The Damned).

Matt Webster: I’ve known Nick since 1983 when he was a promoter for weekly punk gigs in our home town of Bradford and nearby Leeds and Keighley. I was in a hardcore punk band called The Convulsions at the time and we used to hassle him to put us on as support act to bigger bands like the Subhumanz, which he eventually did, just to shut us up! I went on to be in quite a few original bands in the years between then and 2007, including Western Dance, Primate, Zed, Grim and Kwai Chang Caine as well as spending twenty years on and off playing in a blues three piece and standing in as drummer for may other acts. In 1998 I set up a studio and label, Mutiny 2000 Records with a small group of friends including Jont (Psycho Surgeons) and Rob Heaton (New Model Army) at a venue called The Mill in Bradford. I had always been interested in recording and had been heavily involved when the bands I was in put out records. In 1996 I damaged my hand and couldn’t play drums for nine months so I went to study audio recording and production at a local studio and started a two year College course on Music Technology which led to me convincing friends that we should set up a studio/label and have control of our own recordings. Over the next few years, working with Rob Heaton we recorded and released a couple of compilation albums as well as full albums for my band Kwai Chang Caine and others. We also re-released old material from many Bradford bands, cleaning up audio and producing CD albums from tracks that were only on vinyl, quarter inch tape and even cassette. This included albums by Zed, Psycho Surgeons, Western Dance and New Model Army (‘Lost Songs’) who had the studio next door. This led to various projects including the unfinished album with Wild Willi Beckett and the posthumous ‘ashes; single which we were due to record with Willi actually on the day he died but recorded later, adding clips from him from other recordings to the song. In 2007 I became very ill with a serious arthritic condition that damaged my spine and led to years of being in constant pain, unable to walk and certainly unable to play. In 2016 the 30 year anniversary of my band Western Dance made me try and play drums again. I found I could still play, luckily, and did a reunion gig. After that I joined two covers bands and we had a nice room to rehearse in which Mark Cranmer (who I began my musical journey with in 1980) had set up which was also was good to record in. I also had a good computer which I set up for recording and mixing at home and started recording a few things. I had planned to record jams with people from my bands and use these as a basis to put some of Nick’s poems and stories over (at this time I was working on his website). So, some of the sessions on the first album started that way and more came from me on drums and Mark Cranmer on bass laying down some constant groove I could work on later. I dug out my guitar (again, not touched for 10 years) bought a new bass and started filling in the parts and expanding on the recordings we had. Later I asked other former band mates, some now living in different parts of the country, to contribute parts, particularly the sax of Keith Jafrate and the flute of Chris Walsh which help add a different flavour to the music. This became a good way to play with old friends who can’t be in the same band together full time due to circumstances and distance but can still contribute to a track and be on an album.

How would you compare it to ‘Shooting The Messenger’?

‘Shooting The Messenger’ was the product of Matt and me experimenting with how to blend his music with my words. It was an exciting process and resulted in an album that’s unlike anything else I’ve ever heard. When we then came to making the follow-up, ‘Walking The Tightrope’, we were much more sure of ourselves, our methods and aims, and how to work with all the contributors. I’m really proud of both albums. The first was a great way to introduce our work. The second was more self-assured, confident, and polished.

Matt Webster: The first session for ‘Shooting The Messenger’ was a reunion jam by The Moon – a jazz band that hadn’t played together since the 1980s. Mark Cranmer – bass, Keith Jafrate – sax, Emmanuel Williams – guitar with me on drums (I had actually played the very first gig with The Moon in 1986). Other tracks began as jams at the end of other recordings with Jack Atkinson on guitar or with Stephen Andrews and Jonny Botterell (Plastic Letters) and the rest were bits and pieces I’d started testing recording drums at home. Nick’s vocals were added at an early stage, sometimes just to a drum beat, and I added the other instruments before bringing in Keith (sax) and Chris (flute). For ‘Walking The Tightrope’ I actually had a plan! In January, February 2020 I did one session with Jack (guitar) and one with Mark (bass) as well as two sessions where I went down with Nick and recorded five or six drum tracks, me just playing to a click. This meant that when lockdown happened I had a lot of drums recorded that I could work from (I only ever use real drums – can’t stand midi drums!) I began working up those sessions into songs and asking old friends who had facilities to add parts at home to contribute, this led to Simon Nolan (Zed, Anti-System) and Wulf Ingham coming on board. Wulf and I had last played together in 1985 and had planned a session that was cancelled due to Covid. He added a riff to my drums to which I then wrote an intro and middle section before asking Paul Gray from The Damned to play bass; this became the track ‘Best Wishes’.

Here in Bradford we were in lockdown until July and then again in October. In the time in between we managed to get down to my band rehearsal room to record all of Nick’s vocals in two sessions, plus a day for Dee Bo General’s vocals and a day each for Keith’s sax, Chris’s flute and a session with Wulf during which I put down more drum tracks for album three. I also managed to fit in recording a reunion single with my old band, Western Dance! We had to give up renting that room in October and move my drums and recording gear into storage – another result of the pandemic – but by then I had everything I needed to mix the album. The third album is well underway apart from the vocals and the sax and flute which we will have to find a time and place to record. It features the same musicians with Paul Gray playing on three tracks this time.

There’s also a great collabo you did with Thies Marsen, ‘Death & Other Destinations’.

Thies Marsen: I found the album ‘God Save Us From The USA’ already in 1987 and some years later, when my equipment had become better, I began to set it on music, which lasted some years: In fact until 2001, then I was satisfied with the track and finished it – but it took another few years til I sent it to Nick.

Here’s the thirty-five year-long story. In 1987, my paired poems, ‘Noo Yawk Chant’ and ‘Sheer Funk’ were the opening track on side one of a compilation album called ‘God Save Us From The USA’. Fourteen years later (2001), German ex-punk musician, Thies Marsen, found the album, liked my poem, and set it to music, using a cut-up of my vocal recording. Nine years later (2010), coming across my email address, he sent me his recording. I loved it. Without ever meeting or even speaking to each other, we began an email and postal correspondence that led to a few more tracks. Two years later, in the late summer of 2012, Sound Shack Records released our debut disc, a 3-track CD called ‘The Bavariations EP’ (because Thies lived in Bavaria). A German radio station commissioned Thies to make a radio documentary about this duo who’d never met or even spoken. He, therefore, phoned me in April 2013 and then came to visit me in Bradford for a couple of days in early June to make the recordings for the documentary. That’s the only time we’ve ever met. Over the next few years I sent Thies more recordings and he, intermittently, sent me songs he’d done using cut-ups of some of these tracks. In 2019, Not-A-Rioty Records released ‘The Bavariations Album’, a CD consisting of twelve of our tracks. Tracks continued to come via email and so, towards the end of 2020, Not-A-Rioty released our current album, ‘Death & other destinations’, a ten-track disc on blood-red vinyl. What’s more, we’re now two-thirds of the way into a third album. They’re great tracks too!

Working with Thies and with Signia Alpha, two very different processes, both resulting in much airplay and some truly excellent reviews, has been utterly unexpected and a total joy. When life persists in offering you bonuses that take you way beyond all your hopes and aspirations, you embrace them. I’m a lucky man!

What else currently occupies your life?

As if the prospect of another album with Thies wasn’t enough, Signia Alpha, matchlessly piloted by Matt Webster, has recorded sufficient backing tracks for two more albums. The first of these, based on stories and poems I’ve written around the world, is to be called ‘The Columbus Memoirs’. It’ll be much rockier than our first two albums and will be a globe-trotting kick against Covid.

My year of daily pandemic poems is to be published in three books. The first, ‘Corona Diaries’, came out a few months ago. The second, ‘The Year The World Stood Still’ will follow in July, with a third to be published before the year-end.

We’re currently seeking finance to extend the film I made about my father. The aim is to do more research as the vaccines allow archives to re-open. The filming is based on my research. I’ve already got much more to add. Our hope is that we can turn our ten-minute film into a thirty-minute documentary which will be shown on TV.

I’ve got several other books in the pipeline. A publisher has asked me to do another book for children. It’s to be a popular fairytale which I’ll turn into poetry that will be lavishly illustrated. I’m starting work in the next two weeks (i.e. before the end of June 2021). I have a new phone with a great camera and a Fitbit which demands that I do long walks every day. I take photos and have recently been writing poems to go with these images. I’ve posted these (pic + poem) on a couple of Facebook pages over the past few weeks. Feedback’s been great. They’ll become a very smart book printed of glossy colour-picture-quality paper and will probably also be available as an internet download. I’d love to do a film with me reading them over my photos.

There are two more books in the pipeline – both nearing completion. The first is based on true stories I’ve written for columns I’ve had in various magazines (currently RnR). I hate autobiography because it’s inevitably overloaded with me-me-me egocentric vanity. These are stories about people and events which have had an impact on my life. They’re memorable incidents, individuals, occurrences, conversations, and observations that have amused, scared, shocked, and/or entertained me. So… they’re not about me, except as the person recording what’s happened around him. This book’s to be called ‘My Life Sentences’. I have a publisher interested and waiting for me to find the time to finish the bloody manuscript! I shall do so… soon… ish. The second book also has a patient publisher waiting for me to submit my manuscript which is two-thirds done and can be found on my website. It’s the history of the hundreds of punk gigs that I ran. When that’s finished, there’ll be a follow-up book dealing with the alternative cabaret gigs.

I’ve much more to do. I want to finish and publish several incomplete novels, complete two or three political books which I’ve already researched and part-written, and publish several other poetry collections which are written and ready to be released. Life’s an endless buzz!

Thank you. Last word is yours.

In September 2021 I’ll be 71. In my head, I’m young with decades yet to live. Though twice vaccinated, in Covid’s head I’m one deadly new variant away from death. Genetically, judging by my long-lived parents and grandparents, I’ll die within 25 to 30 years. I’m fit and healthy but have moderate asthma and low-level prostate cancer. I could die today or tomorrow. I won’t. The truth is, screw you, death. Of course I’ll die, but my voice and personality will live on through my published and recorded words, including this interview. Read it now while I’m still here. Read it again when I’m dead. See… There’s no difference. I’m still here. This is immortality.

Klemen Breznikar

Nick Toczek Official Website / Facebook / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube

Mutiny 2000 Official Website / Instagram / Bandcamp

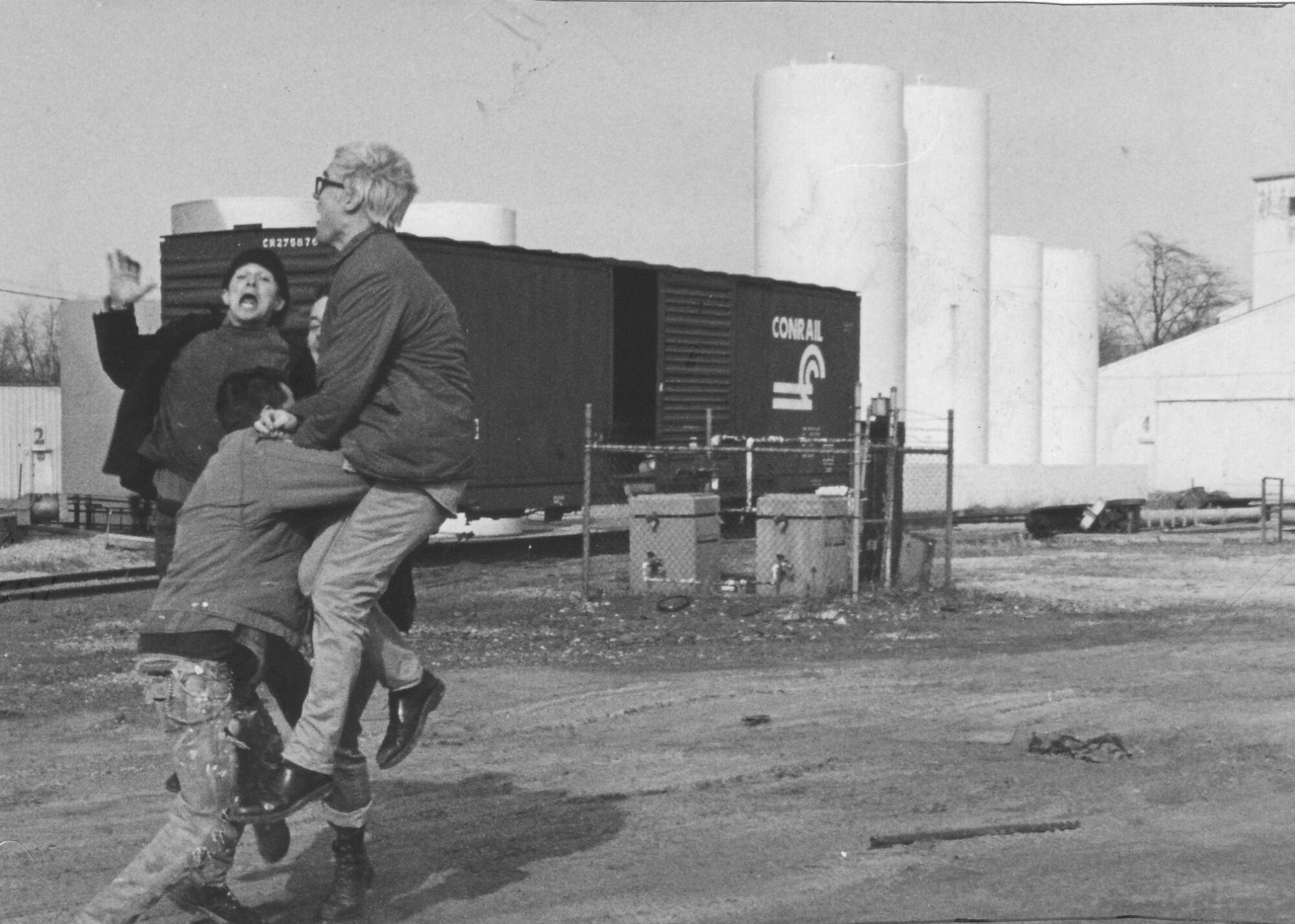

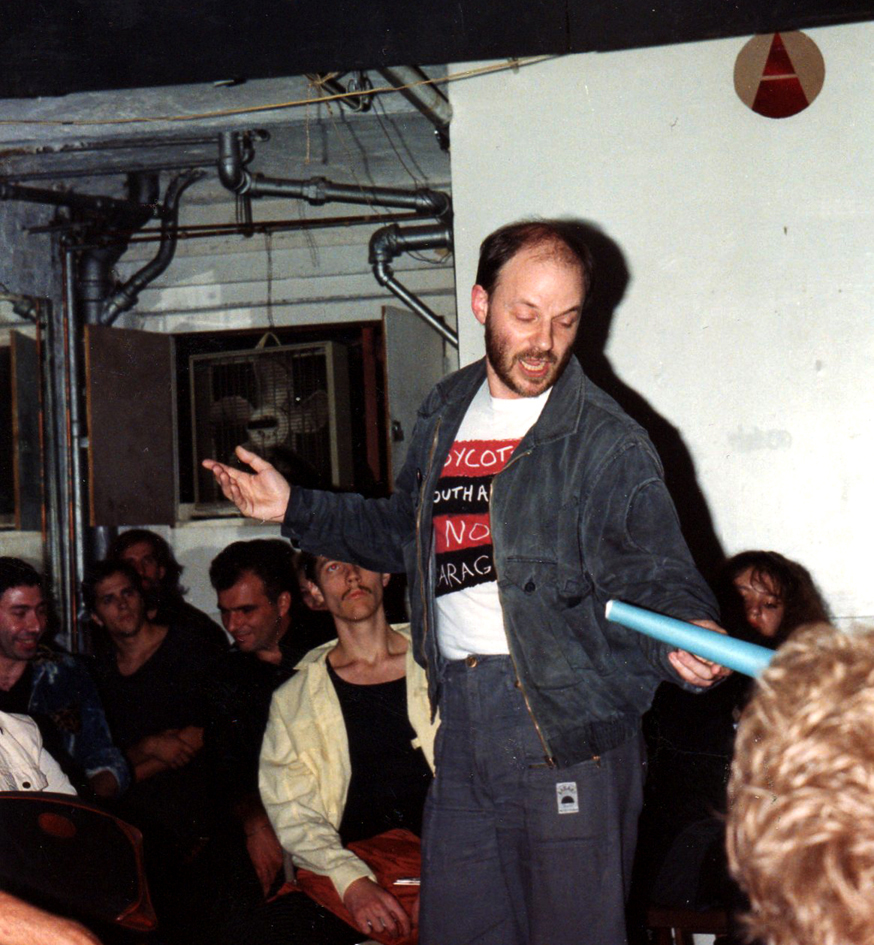

Headline photo: Nick Toczek fronting Ulterior Motives, Vaults Bar, Bradford, 1980 (bassist Rick Green behind)