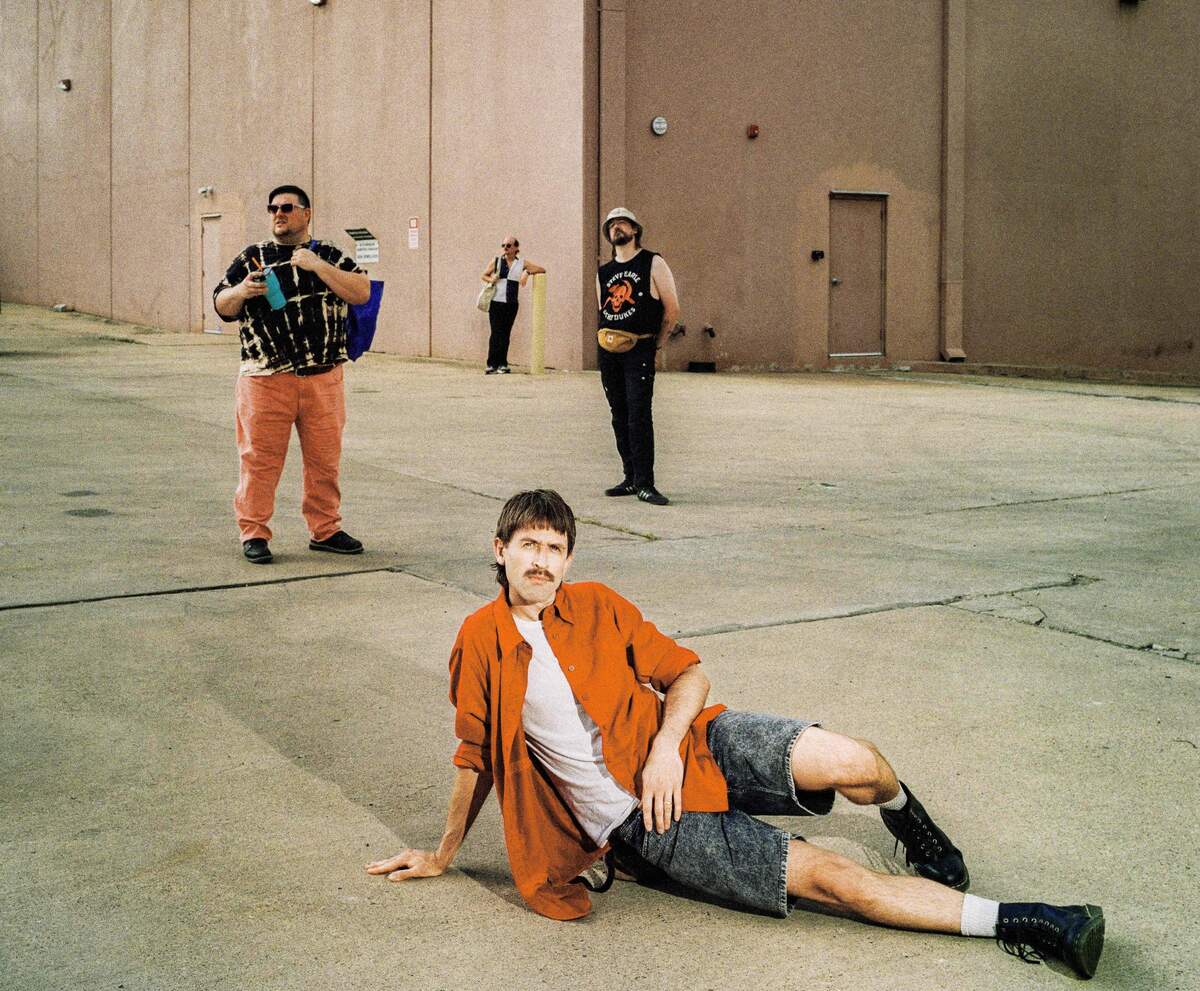

Big Bill Drops ‘Young Men Of The World’ Ahead of ‘Sick Myth’ LP

Austin based art punk band Big Bill has shared ‘Young Men of the World,’ the final single from their urgent new LP, ‘Sick Myth,’ out this Friday via TODO Records.

The bouncy, kinetic track arrives with an equally high energy video. Known for their bending sound, the song mixes egg punk and ska energy and delivers a rare piece of direct advice to the next generation of men. The band states the song features sentiments as direct as “Don’t put yourself above women” and “Don’t be a bad guy, don’t be a cop.” However, Big Bill’s characteristic irony quickly appears in the bridge which suggests, “Actually, don’t listen to me; turn off this song, go plant a tree.” A searching saxophone solo by fellow Austin punk Billie Buck (of Sailor Poon) adds to the track’s frenetic atmosphere.

‘Sick Myth’ explores the spiritual ugliness of America and is a commentary on the nation’s sad, desolate, and commodified landscape. The album addresses themes like death and corporate psychopathy, creating a vital roller coaster through the wreckage of late stage capitalism.

The band faced an intense challenge to complete the album quickly due to lead singer Eric Braden’s upcoming move after fourteen years in Austin. They used a brand new method of writing, crafting parts in brainstorms and digitally mixing them before learning the tracks live.

The winner of this year’s “Best Punk Band” at the Austin Music Awards, Big Bill is set to play their record release show on November 22nd at Radio/East in Austin, TX. The event will be their annual raucous party, Big Ball 8, which features local bands and art installations.

Headline photo: Big Bill (Credit: Pooneh Ghana)

Big Bill Website / Facebook / Instagram