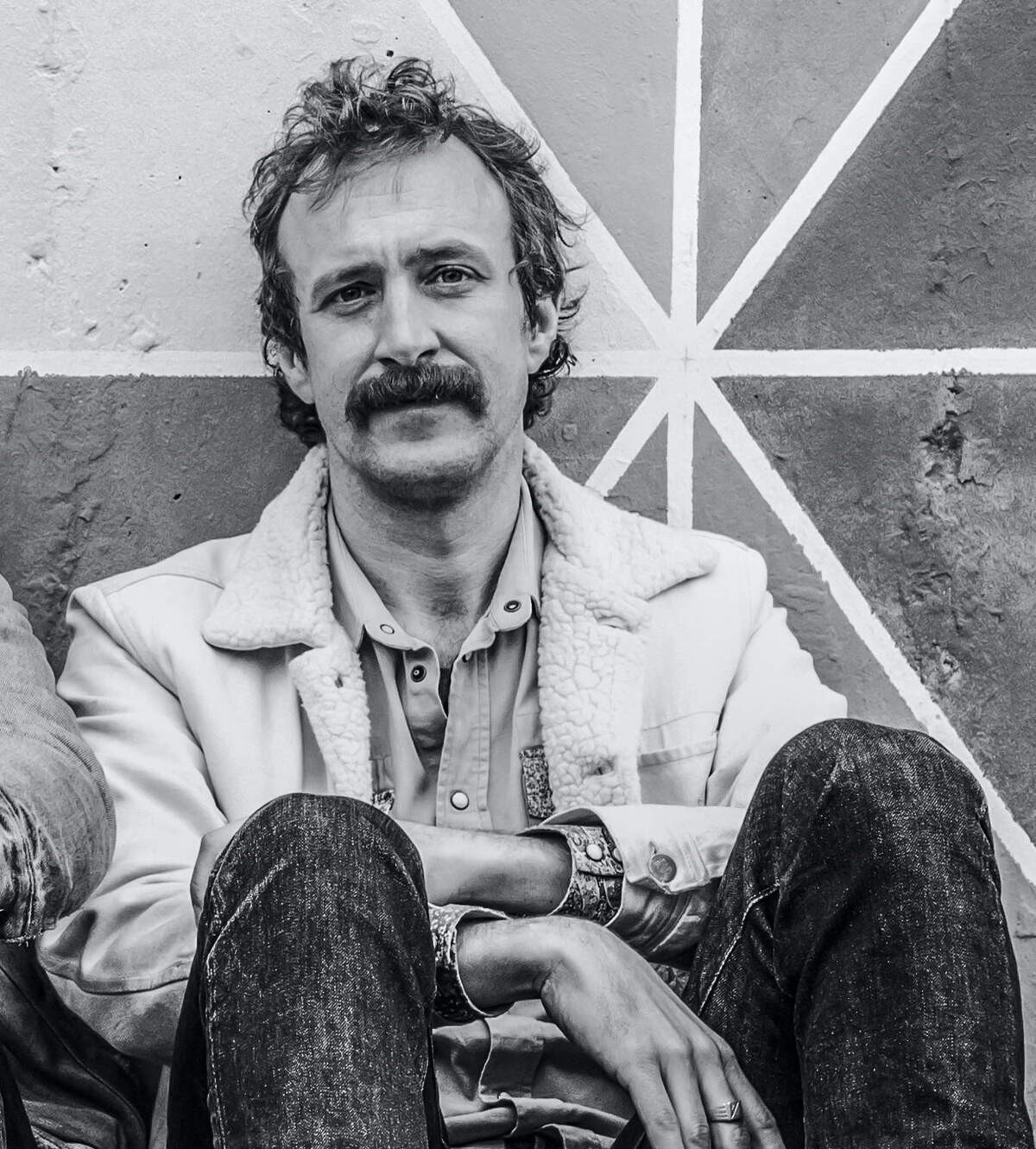

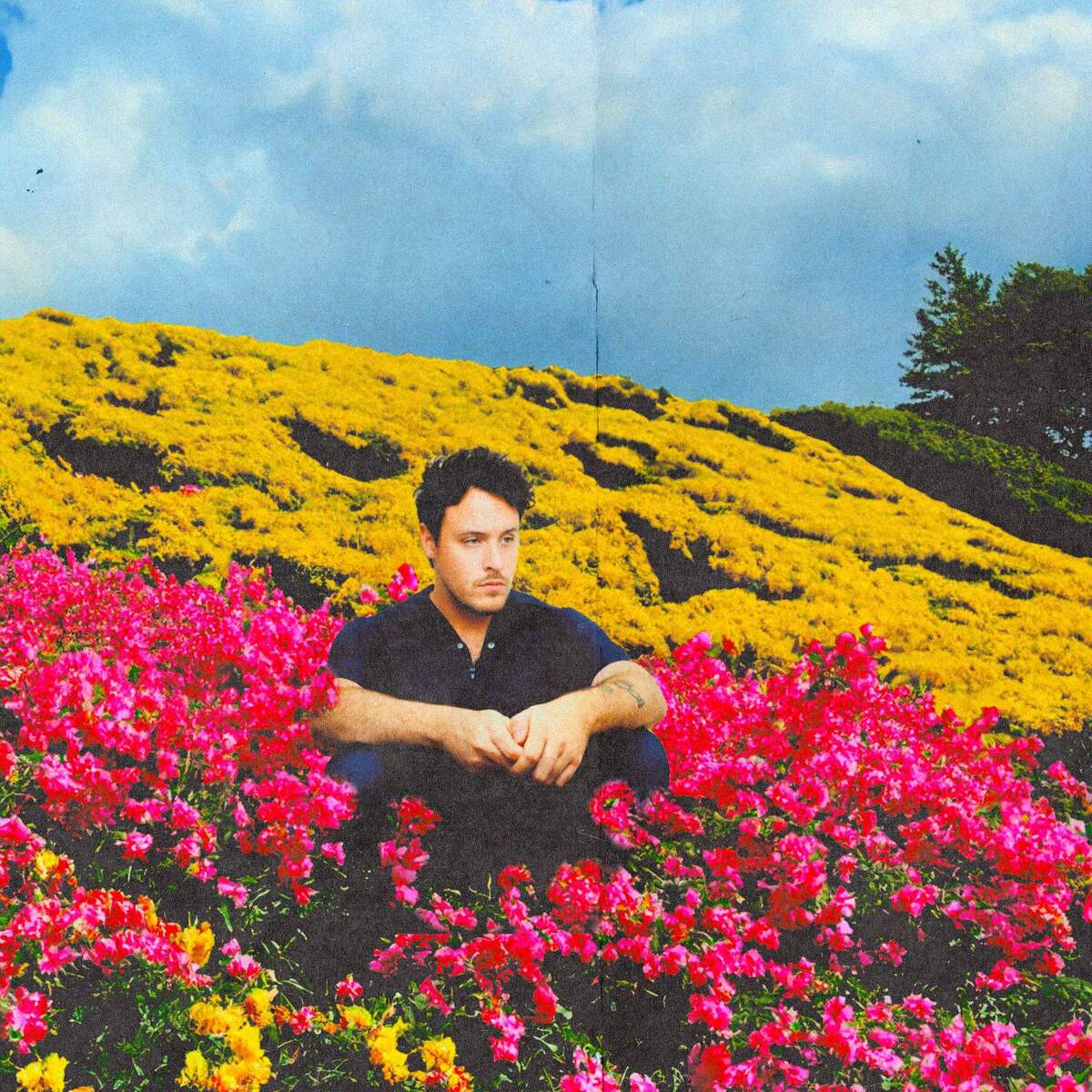

Sven Libaek interview

Sven Libaek is a legendary Australian composer. Sven Libaek’s Inner Space is, simply put, one of the most legendary soundtrack recordings in the history of Australian music.

Your career is absolutely amazing. From tons of recorded albums to becoming an actor. You were born in Oslo, Norway and soon began practicing piano. Your first big breakthrough was performing in the Windjammer film. How did that come along?

When I was a young child in Norway, my father was an impresario who brought famous musicians from all over the world to perform concerts in Oslo and all the other major cities in Norway. So, at the age of 5, I was already going to concerts and getting familiar with classical music in particular, although I remember him also bringing artists like Louis Armstrong and Todd Duncan, (the original Porgy in Porgy and Bess on Broadway. These famous people used to come back to our apartment after the concerts for a late supper, so I actually got to meet them and talk to them about music. Needless to say I wanted to learn to play the piano and started to take lessons even at that young age.

My father was also involved with a famous children’s theatre company in which it was natural for me to take part as a “child actor”. I must have done something right because I started to get children parts in adult plays when it was needed. Through my childhood and into my teenage years I was in more than 40 plays, which finally lead to a lead role in a Norwegian feature film called Nothing but Trouble. During this period I was continuing my piano studies and was planning for my debut on the concert stage. That’s when Windjammer happened.

“Almost everything I have done since leads back to Windjammer.”

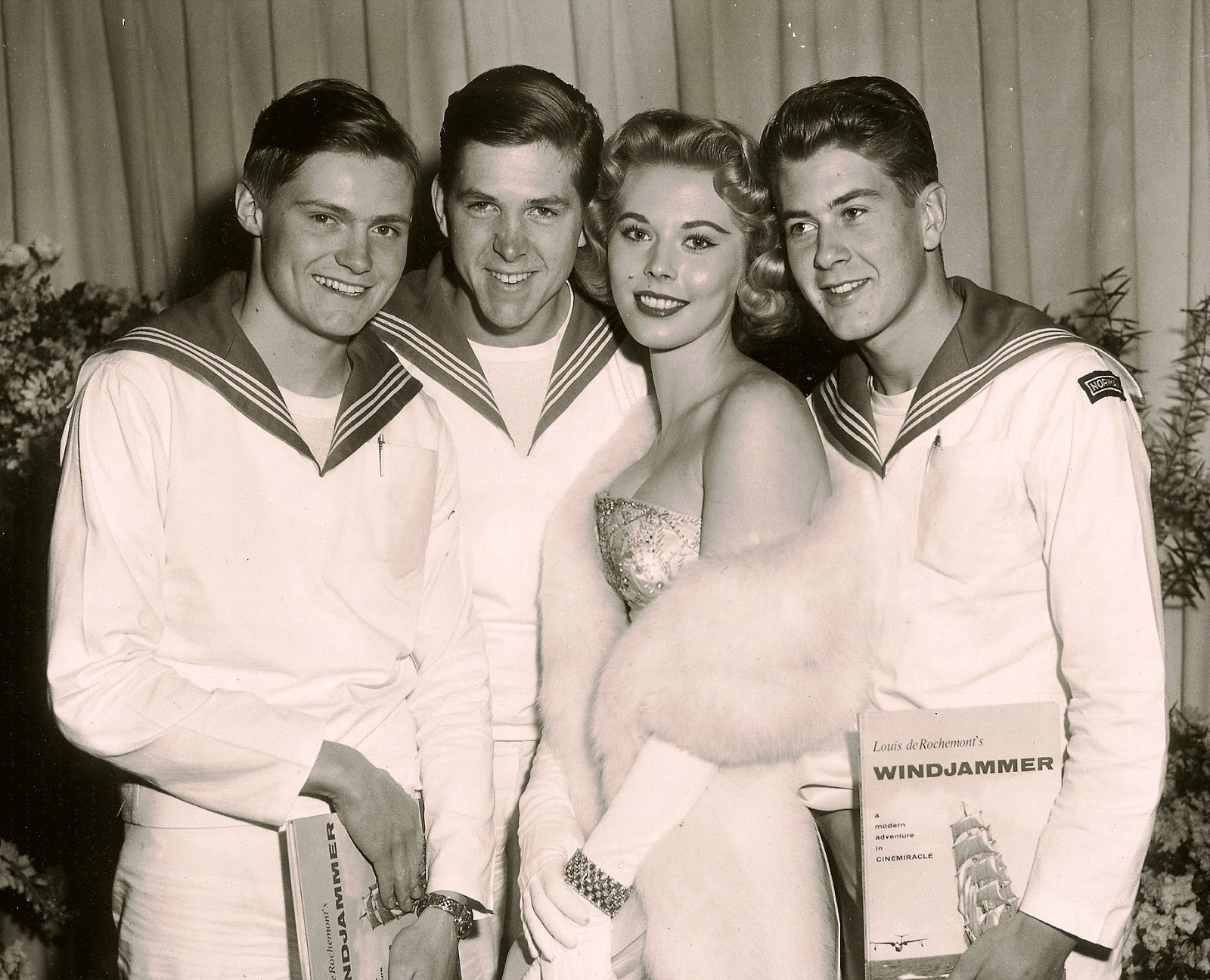

The film Windjammer was very successful. You were also a part of Windjammer music group that eventually got an RCA recording contract.

The famous American producer Louis deRochemont had the idea to do a film about a cruise on a sailing ship. Norway had three operating windjammers, used to train boys for the vast Norwegian merchant marine. Louis came to Norway to try and rent one of these ships for a year and take it on a film cruise to Madeira, the Caribbean and the United States. Although the film was to be an adventure documentary, he felt he needed half a dozen “actors” among the crew, who would have some dialogue scenes to tie the story together etc. Having just finished the feature film, I applied for one of those parts and was picked. Little did I know at that time that it would set me off on my future career in music. Almost everything I have done since leads back to Windjammer.

The ship and the crew was supposed to be gone from Norway for at least 9 months, and my parents did not want me to go without a piano for that long, when I was almost ready for my first recital. They negotiated with deRochemont to arrange for an upright piano to be put on the windjammer. A sailing ship of course is always leaning to one side or the other, so the piano had to be lashed to the bulkhead with solid chains. This all meant that I could do some practising every day, and as a result my parents let me take the part. The chosen actors, including myself became very much part of the crew, setting sails, climbing the rigging, pulling ropes and doing our turn at the wheel. It was a fantastic trip, which turned into a fabulous film. It was shot in Cinemiracle, an improvement of the three camera Cinerama system.

While we were at sea, Louis deRochemont had plans of his own for me, which I knew nothing about. When we arrived in New York, he took me to his office and told me that he had arranged for me to play the Grieg Piano Concerto with the Boston Pops Orchestra, conducted by the legendary conductor Arthur Fiedler. I almost fainted and told him I was nowhere near ready for anything like that. But he said he had arranged for a famous pianist and music teacher in New York, Bernardo Segal, to work with me. Also the performance would be filmed and was to become a special sequence in the film. Three weeks later we recorded the first movement of the Grieg in Boston Symphony Hall, and the next day Louis flew the whole orchestra to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, set them up on the dock, with me at the piano and the ship in the background. After filming the opening of the movement with the Boston Pops, Arthur Fiedler and myself, the camera moved to the most magnificent pictures of Norway. The fiords, waterfalls, mountains and other beautiful landscapes. It became THE sequence in the film, and I was part of it.

After the filming on the dock we sailed back to Norway, north of Scotland in some heave weather. We were greeted back in Oslo with big celebrations, functions in Town Hall etc. and it was time to get on with our lives. But that was already destined. Within weeks Louis wanted the “actors”, including me, back to New York to film some studio scenes to tie things together. To cut a long story short, when the filming was finally completed, three of us, Harald Tusberg, Kaare Terland and I decided to stay in the US and apply for student visas and continue advanced studies. Harald got into Yale, studying drama. Kaare got into Dartmouth studying business, and I applied to the famous music school Juilliard in New York. I spent the whole summer at Louis’ farm in New Hampshire, practising for my audition. Back then, (and maybe still), when you audition for Juilliard, you do so from the stage of their concert hall. All the piano teachers sit in the back of the hall, where you couldn’t see them. You are not accepted by a committee. All you have to do is to be accepted by one teacher who is willing to take you on and you are in.

Again Windjammer rescued me. By then it had been released in New York. My audition did not go well I thought. They stopped me playing after a few bars of each piece I had selected, and when I was told to finish and come down from the stage, one teacher, Joseph Raieff, approached me and confirmed that he wasn’t that impressed. However, he told me that he was sure he had seen and heard me play before, and he had been impressed. He asked me if I had ever given any recitals in the New York area, and of course I hadn’t. All of a sudden it occurred to me that maybe he had seen Windjammer. I mentioned it and he called out “that’s it. I thought you were very talented. Not so good today, probably nervous. I’ll take you on as a student”, and just like that I was a student at one of the most famous music schools in the world.

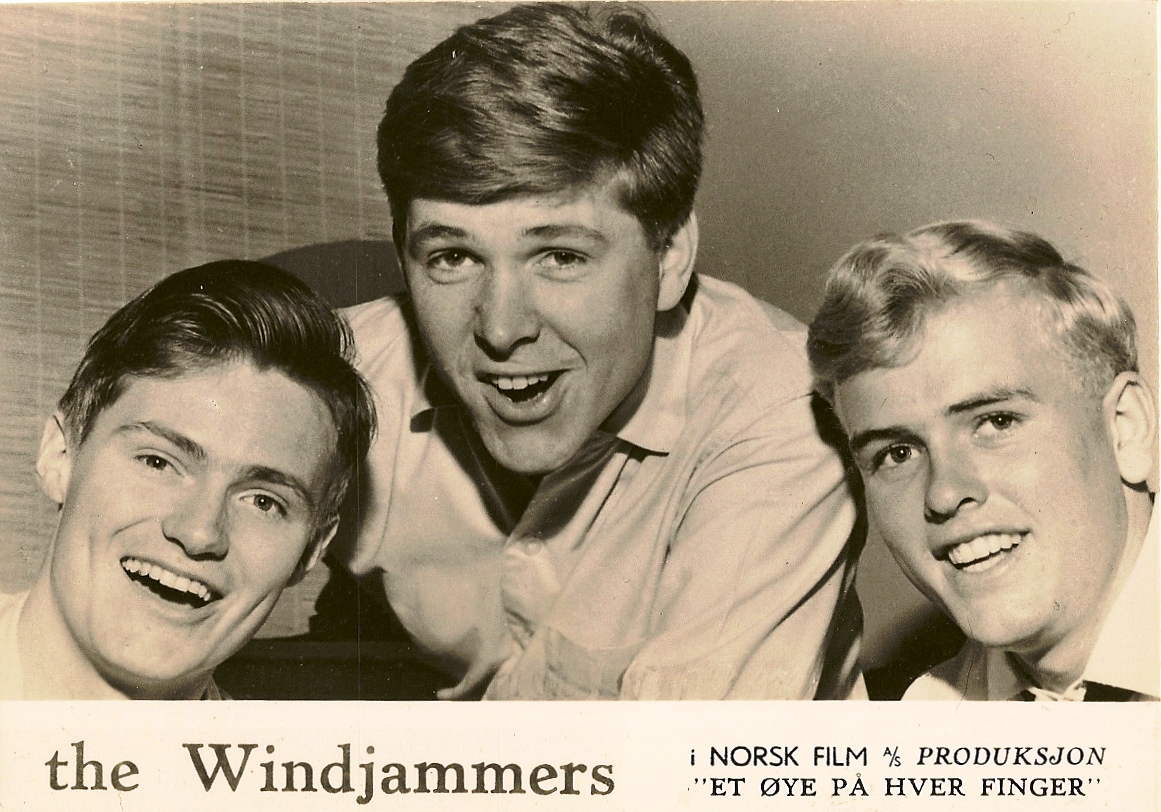

While all three of us were at our respective schools, Windjammer opened all over the place. The film company hired us during school holidays and breaks to travel to different cities and promote the film on radio and on TV. We decided to create a singing trio. The Kingston Trio were very big at that time, and I based my arrangements on see chanties and folk material. We attended openings in Los Angeles, London, Oslo of course and many American cities. Now instead of just talking about the film, we could also entertain by singing a few songs. This got us on shows like the Grand Ol’ Opry in Nashville as well as a recording contract with RCA. We recorded an album in Nashville with Chet Atkins and John D, Loudermilk producing. Kaare and I played guitar and Harald was the lead singer. I must say I thought we sounded pretty good, and obviously so did other professionals.

You visited Australia on promo tour for Windjammer film and decided to stay.

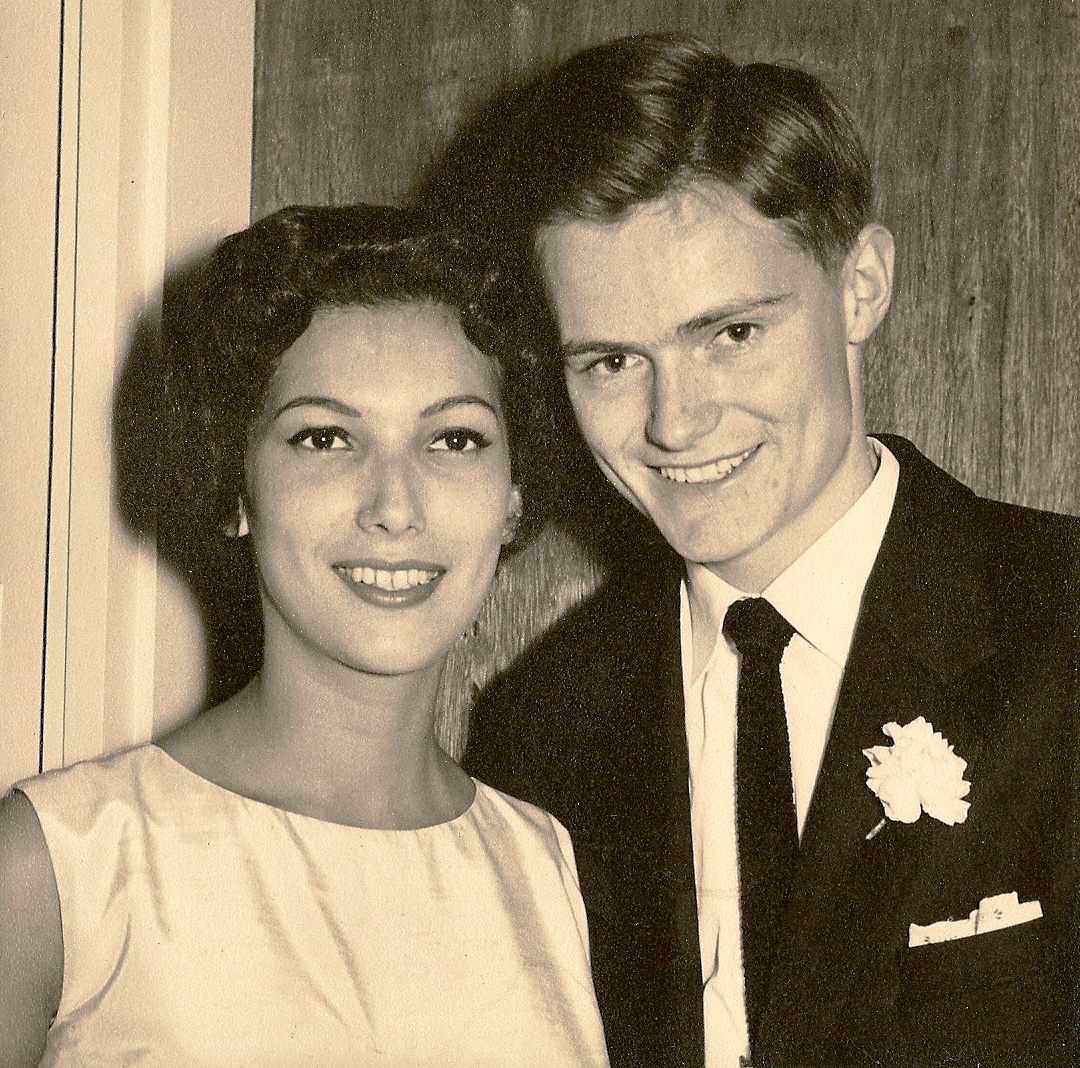

Our New York agent, famous drama coach Claudia Franck was a close friend of the owner of Channel 7 in Sydney Australia. She told him about us, and he hired us to come to Sydney and appear on his channel, which had a well known variety show. So during the summer holidays we jumped on a 707 and headed for Australia. We had a great time and loved the country. When our engagement was over Kaare returned to Dartmouth, but Harald and I decided to stay. I was newly married, so I sent for my wife and Lolita arrived in Sydney soon after. We hired a new third member, an Australian Tim Gaunt and continued performing.

After a few months we got an offer from Norway to play leading parts in a new feature film called “An Eye on each Finger.” We jumped at it. It was a comedy/drama and love store set in an army camp, and it was a big success in Norway. After the film was finished, the group broke up for good and Lolita and I, who had both fallen in love with Australia, returned to Sydney.

“Miles (Davis) was a perfectionist.”

In the 1960s you were hired by CBS Records Australia and released a lot of records.

As soon as we landed I started looking for a job. I even sold encyclopedias door to door for some time. I went and saw people working for the different record companies, hoping I could land a job that involved my musical knowledge. I heard that the boss of the Australian Record Company, (US Columbia Records’ representative in Australia), Bill Smith, was looking for an A&R man to produce records with Australian artists. My timing was perfect and I got the job. I spent four years as their A&R manager. It was a great company to work for, because he was not only interested in pop hits. I got to produce folk artists, classical and jazz artists as well as rock groups. I had a big hit with a surfing record called Bombora which paid for some other records that didn’t do so well. I also got to perfect my arranging, I wrote the backings for many of our pop singers, and also wrote several original songs for them with Lolita writing the lyrics. Bill Smith even sent me to New York to attend the Columbia Records convention, where I met people like Tony Bennet, Robert Goulet and Aretha Franklin. I also sat in on a recording session with Miles Davis and the Gil Evans big band. It was a great experience, and I learned a lot about producing records. Miles was a perfectionist. I remember they fired a horn player just for being 5 minutes late to the session. I guess the principal was important, because the whole band sat and waited for more than an hour, on full pay, for a new horn player.

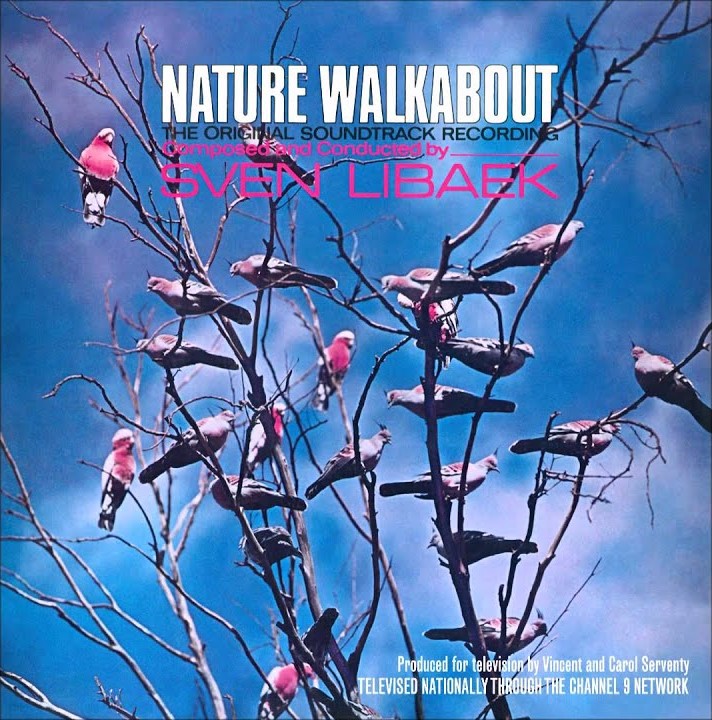

After four years working for ARC, Nature Walkabout happened. I though I could compose the music to the series while still hanging on to my job at ARC, (which now had become CBS), but Bill had other ideas. He said you either work for me or you work for yourself. Lolita’s father in New York had a sewing factory, and I remembered what he had told me years before. Something like “you never get rich and successful working for somebody else”. It hit home and I decided to take the plunge and go free lance. Since then I have never looked back.

You left CBS to work on your own music production company.

Freelancing immediately seemed to have been a great decision. CBS almost right away hired me back to produce records on a freelance basis until they could find somebody to replace me permanently. I also got projects from other record companies to arrange and produce albums.

I had done the music to a documentary about the mural in the BP building in Melbourne called Man and a Mural. It was highly regarded in the trade, and if I remember right won an award, I think in New York. I didn’t know it at the time, but it was this documentary that got me the Nature Walkabout job. The film editor of the Man and a Mural was to become the editor of the Nature Walkabout series, and he recommended me to Vince Serventi. The series was about Vince packing his whole family into a van, and travel all over Australia, filming episodes featuring the flora and fauna and the most beautiful landscape scenes of this great country.

One of the first project was for a film by Vincent and Carol Serventy. They left Perth on a journey that would take them around the country documenting many natural wonders. The result was a TV series Nature Walkabout.

This series was perfect for me. People often say the new immigrants to a country they fall in love with, often feel stronger about the place than the people who live in it. I wanted to create what I thought to be the “Australian sound”. Since my A&R Manager job at CBS I had become very familiar with Australian folk songs. I had put one of Australia’s most prominent “folk singers” under contract. His name was Gary Shearston, and he recorded a number of albums for us, covering almost the entire repertoire of Australian folk songs. For Nature Walkabout I immediately thought of using the original basic instruments like the harmonica and the guitar. I added vibraphone for the shimmering heat, and “hard” brass for the often harshness of the Australian landscape and woodwinds for the beautiful birds and strong winds sweeping the desert “outback”. I even included a few bars of the folk song Botany Bay in my main theme. According to Vince Serventi and the other members of the production staff, as well as the reviewers, I had hit the nail on the head. In my area of “show business” one thing leads to another – or not – but soon after Nature Walkabout I picked up the score to a feature film called The Set. It was produced and directed by an American, Frank Brittain. It was a very controversial film when it was released. It contain nudity as well as homosexual subjects, something never touch upon in Australian movies. I had one review that said “the only good thing about this movie is the music”.

I guess under normal circumstances this should have pleased me, but it upset me greatly. This reviewer obviously did not appreciate the significance of what we were doing. The Set is now a “cult movie” and part of Australian film history, and Frank Brittain remained a friend for life. I also did a TV movie, also for Frank, called Lady and the Law. Frank eventually moved to Italy to do films for the Vatican, and we have stayed in touch throughout the years.

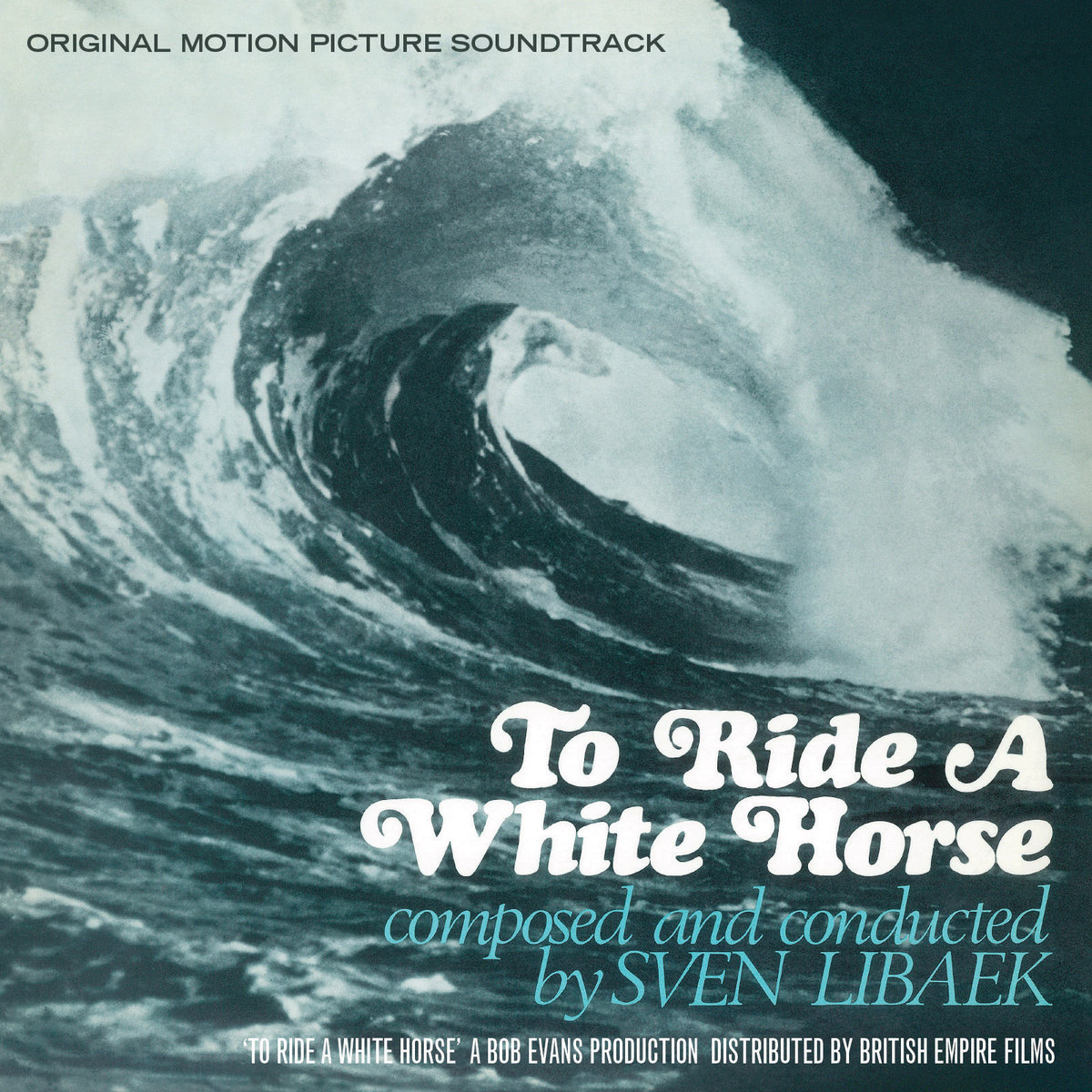

Then there was To Ride a White Horse and in 1969 you began working on a very big project called Australian Suite. You were exploring locations that affected you during your travels around the country. What are some of the strongest memories from recording it and what was the concept behind it?

To Ride a White Horse has now become another “cult movie”. It was a surfing film, and unlike other surfing films, rather than just putting a rock music track behind it, we decided to treat it like a proper feature film and give it a “feature film score”. It was directed by Bill Evans and featured, what is now, the legends of Australian surfers. It was written by Ted Roberts, a personal mate, who I worked with on many of my projects, including as a writer of lyrics for many of my songs throughout my long career.

We even wrote a stage musical together, which was never produced as the money could not be found, but that’s another long story. The score to Ride a White Horse earned me my one and only award, as the theme won me the best instrumental of the year of release. The film has recently been re-released on DVD and Blueray, so projects of the past are catching up with me on a regular basis. The music side of film and television is fascinating to the composer. The idea that I would be able to pay bills with royalty checks from projects I worked on 40 or more years ago is astounding. With the “invention” of the internet, people can now download music, that up the then, was more or less lost for ever.

A lot followed, including My Thing, Boney and Ron & Val Taylor’s Inner Space which was actually a shark documentary soundtrack for 1973 Australian television series Inner Space.

If I were forced to select one project to be my favourite of all time, it would have to be Inner Space. Ron and Valerie Taylor were famous divers who through a long career set out to prove that many perceptions of under water creatures were false. I still have in my mind the scene where Valerie is swimming among 20 or so Grey Nurse sharks, to prove that they are not dangerous to humans. She patted them, kissed them and they cuddled up to her and looked like her family pet dogs proving once and for all that they DON’T EAT PEOPLE.

“I try to find some “key” words that describe the mood of the film or series. “

I have a system that I apply every time I score a film or a TV series. I try to find some “key” words that describe the mood of the film or series. When I sat down and watched the brilliant under water photography of Ron Taylor, the key word that came to me almost immediately was “cathedral”. As I watched each episode, other words were added, “wet”, “water” “bubbles” “slow motion”, “mysterious”, “danger”, “deep” and “beauty”. The bass flute was the perfect instrument for this series, and I used it in both the opening and closing titles, as well as frequently in the episodes. I hired the cream of the crop of Sydney based jazz musicians, so I knew my score would be perfectly interpreted.

Ron and Valerie Taylor defined Inner Space as the antithesis of Outer Space. The world which man inhabits is a solid mass, governed by the force of gravity. It is here that man moves and has his being. Above him and stretching into infinity, is Outer Space. Surrounding him, covering three quarters of the world on which he lives is Inner Space: the oceans, seas, estuaries, rivers and lakes in which, as much as in Outer Space, man is alien. In the past century man has learned to live in Outer Space. For countless centuries, man has ventured upon Inner Space, but few humans have learned how to live with it.

This, then is Inner Space which Ron and Valerie Taylor explore in thirteen, thirty minute colour specials, each different, each exiting and each adventurous. It truly was a most exiting and challenging series to compose music to, and the score would survive through many decades, later to be discovered again by new directors and record companies almost 40 years after it was first composed. I have always been an animal lover, and Inner Space also taught me much about sea creatures and the often non substantiated “fear” we have for many of them.

The series also gave me some great musical cues titles for the soundtrack album like Sound of the Deep, Music for Eels, Dark World, Island of Birds, Turtlemusic and Attacking Sharks, just to mention a few. Some of my Inner Space music is extremely difficult to play, from the rhythm pattern in the main theme, to the melody in Sounds of the Deep, not to mention the guitar part in Music for Eels. I could never have achieved it without the best musicians Australia had to offer.

Library Music was pretty big back then?

Library Music was very big in the 60s and 70s, for all I know, probably still is, although I haven’t done a library album since then. The idea is of course to produce several tracks with different moods from love themes to exiting chases etc. These themes can then be licensed to producers of films, TV shows or series, commercials etc. for a much lower fee than it would cost them to hire somebody to do original scores and record them in a studio at great cost. As a composer, I have no problem with this. We still share the copyright with the publisher/producers of the albums, and every time one of our tracks are used, we still get our performing rights royalties.

What I also found very interesting, and sometimes amusing, was how and where some of my tracks were used. When I lived in Los Angeles, I happened to come across an evangelist radio show, and the theme they used was a track from my My Thing album. Also on a trip to Las Vegas I sat there playing the slots, listening to my own music over the speakers. The same thing happened frequently while sitting at an airport waiting for my flights to board.

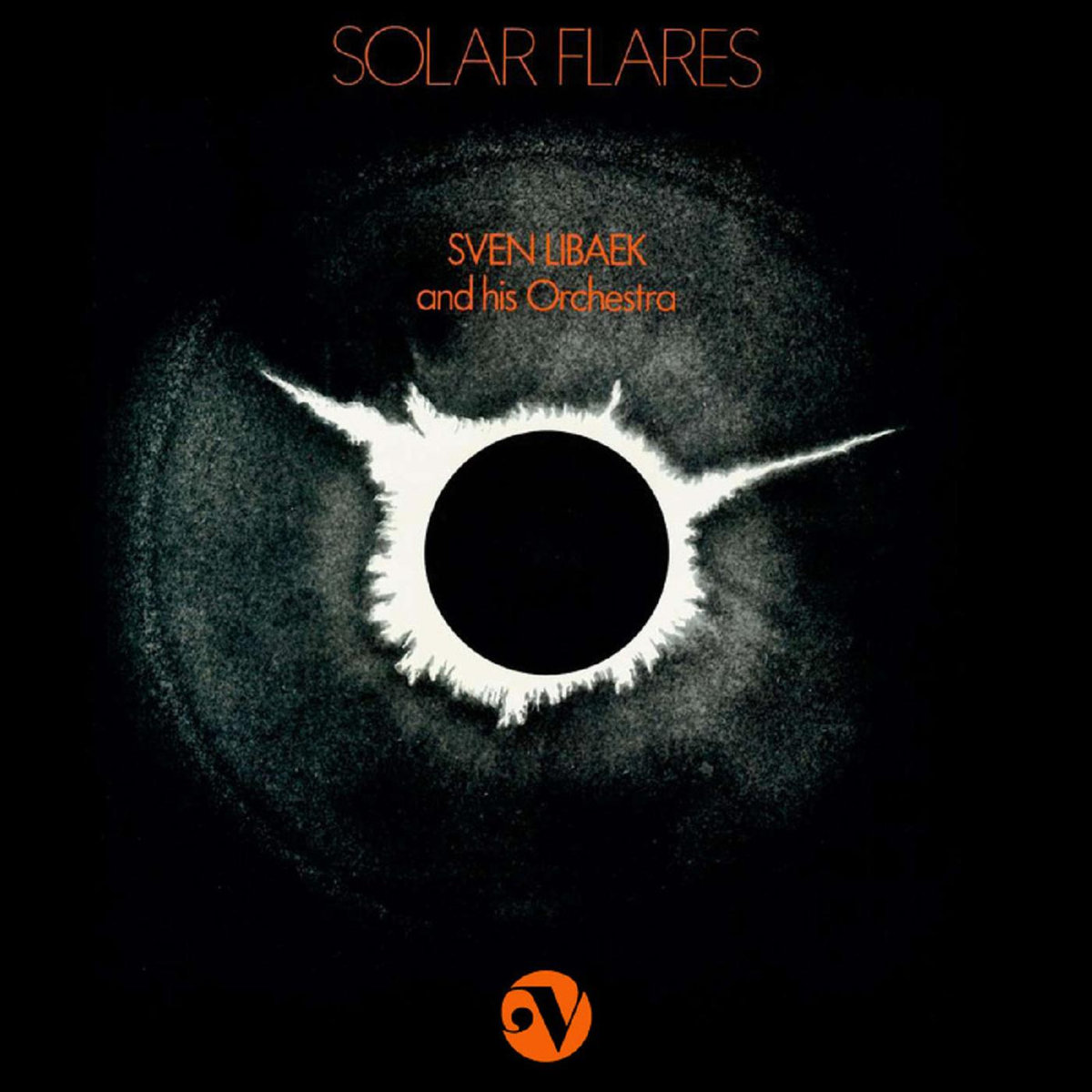

What inspired you to record My Thing or Solar Flares?

My Thing was a typical library album. I set out to compose 12 tracks, all different, to suit all sort of different moods that might crop up in a film or commercial for a product. Solar Flares was very different. A young guy in Sydney had made a synthesiser of his own design. It was the time of the Moog being used in recordings all over the world. However, the one this guy designed was totally different. It had sounds that nobody else in the world had, so I jumped at the chance of being able to record tracks that would sound so unique. A “outer space” theme for the album was a given under the circumstances. This LP which have now been released a couple of times on CD has become a bit of a cult album worldwide. Many of the tracks show up on my royalty statements every quarter, although I don’t know if they are being used as intended by film producers, or if it is just down loaded by new fans. Either way, I don’t care. I think it is a great compliment that some of my work that goes back that far is still enjoyed by new generations of music lovers.

You moved to Los Angeles in 1977.

In 1977 my family and I, (including the Great Dane ODIN), decided to move to Los Angeles and have a go at the “big time”, before we got too long in the tooth. When I arrived there, I was already well known for my “easy listening” arrangements in Australia of famous artist’s hits. I had already done hundreds of them. I was almost right away contacted by a nice guy, Jim Schlichting, who was very involved with licensing these type of instrumental tracks to hundreds of radio stations in the US. He also had the contract to produce music for MUZAK. MUZAK was very big time back then and much later was looked down upon as “elevator music.” However, I had no problem with it. I got to arrange for big orchestras, and it was great training, particularly for my string section writing, which I subsequently became quite famous for. Also the MUZAK contract paid for my North Hollywood house as well as my Lincoln Town Car. You can’t complain about that sort of job. I also got commissions from Lionel Richie’s, Billy Joel’s and Neil Diamond’s music publishers, to record instrumental albums of their hits. It was a very busy time during those first few years since we got there.

I also wrote cover notes for a record company who specialised in classical music. My knowledge from Juilliard again paid off. However, the “big” break, which has sustained me in relation to royalties for most of my life, was the contract with Hanna Barbera to write the music to 10 full length cartoon TV movies. It was more than 8 ½ hours of music. To give a comparison, that would be the same as composing 16 symphonies in classical terms. It kept me busy for 2-3 years on and off. It was so much fun to compose music for The Flintstones, The Jetsons, Top Cat, Yogi Bear, Scooby Doo, Huckleberry Hound and all their other famous characters. We are talking about the early 1980s and these films are still shown on TV world wide, in Europe, also on the big screen. That’s the great thing with animated movies. They never die like some other regular feature films. I used to compose enough music for 3-6 three hours recording sessions. Then I would send photocopies of the scores to Australia where orchestral parts were hand copied. Don’t forget, this was before it became the norm to write music on the computer. I would then fly down to Sydney, conduct the sessions, put the tapes in my specially designed suitcase and fly back to LA and deliver them to Bill Hanna and the music editors. On some of these many trips to Sydney from LA, I would stay a little longer than usual, and get involved in other projects. I did the score to Joe Wilson, a mini series about the life of legendary Australian poet, Henry Lawson. I also did the score to the feature film The Settlement. That was great fun, because it was written by my “old” friend and collaborator, Ted Roberts, and directed by Howie Rubie, who directed The Man and the Mural, which started it all so many years ago.

We stayed in Los Angeles for 17 years, but we had never considered staying there for ever. We knew that Australia was the place for us. After the big LA earthquake in 1994, which luckily didn’t destroy our house, although an apartment building near by collapsed. A few months later we sold the house and car, packed the rest of our “stuff” in a shipping container and headed back to Sydney.

What currently occupies your life? Future plans?

Now, in 2013 I regard myself as semi retired. That just means that I am no longer chasing work and taking producers and directors to lunch. I still have clients that come to me, and I have scored several documentaries, and even a short film from a Norwegian director, Geir Henning Hopland, called Writer’s Block. I live a good life here “down under”. I am the resident conductor of one of Sydney’s community symphony orchestras, so I am back dealing with classical music from Vivaldi and Beethoven to Tchaikovsky and all the other classical composers of great fame. Sydney is a great city to live in. Nice weather and climate, (most of the time), and great outdoor living with the beautiful Sydney harbour. Your readers of Psychedelic Baby Magazine probably saw how great this place is, if they watch us during the Sydney Olympics in 2000. Australia is of course so far away from the rest of the world, and it takes many hours to reach the US and Europe. However, nowadays, with computers and e-mail it is easy to stay in touch with family and friends overseas, and I have done so much travelling in my time that I feel it’s time to stay put.

Thank you very much for taking your time for us. Would you like to send a message to It’s Psychedelic Baby readers?

I am happy and honoured that you think your readers would be interested in my life and work. When I look back I have lived a full and interesting life without any regrets, and I have something I can leave behind which hopefully will not be forgotten.

– Klemen Breznikar

Killer post.Bravo!!!

I love Sven Libaek's music, it's so relaxing and laid back with a real deep groove throughout so much of it, the vibes work beautifully.

I have 9 or 10 albums 4 of which Sven was good enough to copy for me from his own vinyl collection.

I highly recommend "Solar Flares" or the "Inner Space" comp from Trunk Records for newbies.