Fairport Convention’s Simon Nicol Interview: “Time’s Arrow Only Flies One Way”

Few bands in British music have navigated the uncharted waters of change and tragedy with the grace of Fairport Convention.

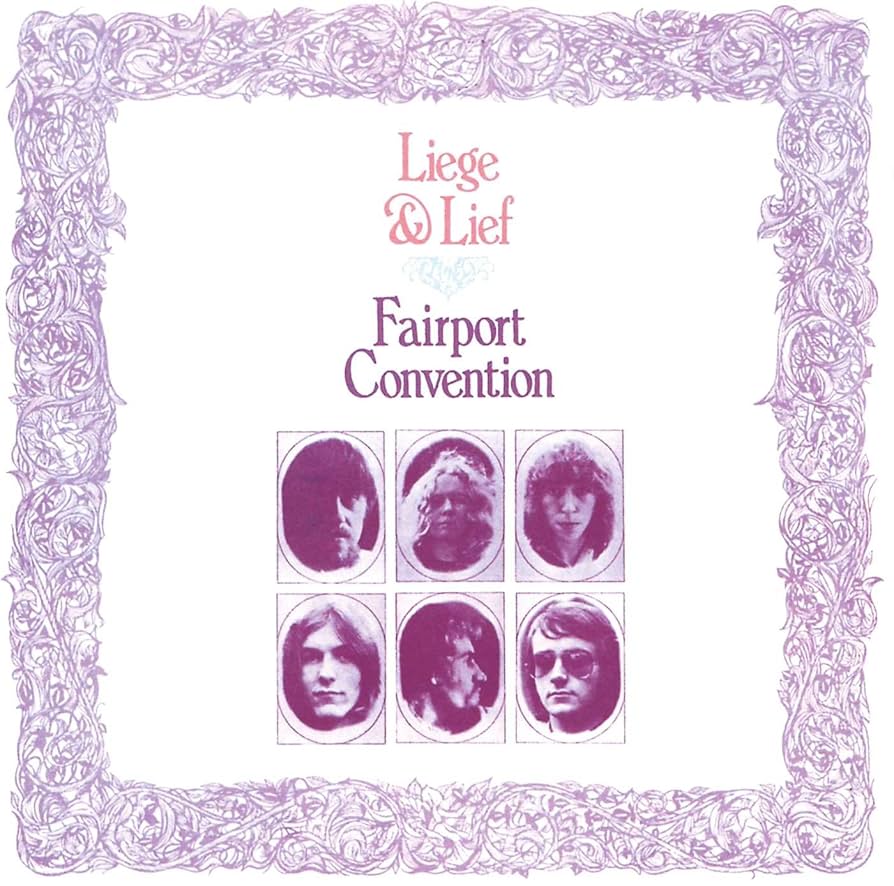

For Simon Nicol, the band’s enduring thread, the line between life and art has never been clear. “Painters, after they lock the doors of their ateliers behind them, will dream of the next brushstrokes they will apply, and musicians are the same,” he observes. It is this seamless intertwining of the personal and professional that shaped Fairport’s seismic shift in 1969, after the crash that claimed Martin Lamble and Jeannie Franklyn. The tragedy, Nicol reflects, was inseparable from the band’s “radical artistic re-orientation,” the turn toward British traditional folk that would define ‘Liege & Lief’.

Yet longevity, he insists, is not merely a matter of circumstance. “Each incarnation of the band has played to its own strengths…Everyone gets to play in their personal zone of comfort,” he says, a philosophy that has kept Fairport resilient across decades of lineup changes. And at Cropredy, the festival that has become a living testament to that ethos, Nicol’s sense of gratitude is palpable: “Nobody can see how grateful I am for my luck in being part of it all, and for having been dealt the cards that I’ve played since 1967.” In Nicol’s hands, history, family, and folk become inseparable threads of the same enduring tapestry.

“The best songs are instantly visual”

The year 1969 marked a profound turning point for Fairport Convention, not only due to the tragic accident that claimed Martin Lamble and Jeannie Franklyn but also the subsequent, definitive shift towards British traditional folk music, culminating in ‘Liege & Lief.’ Given that the band was initially influenced by American folk-rock and even nicknamed “the British Jefferson Airplane” (Harper, Colin. Meet on the Ledge: A History of Fairport Convention. Essential Works, 2000), how does one reflect on the interplay between this personal tragedy and the band’s radical artistic re-orientation? Was the embrace of deep-rooted British tradition a conscious, almost therapeutic, seeking of grounding in the face of chaos, or a more organic, perhaps inevitable, evolution already hinted at by pieces like ‘A Sailor’s Life’?

Simon Nicol: Personally speaking – which of course is the only way I can – I don’t think anyone can separate our private from our professional lives, especially in the world of the arts. Painters, after they lock the doors of their ateliers behind them, will dream of the next brushstrokes they will apply, and musicians are the same. And what happens in every level of our existence will shape who we become as we grow through life. Time’s arrow flies in one direction only, and we cannot replay past scenes until we get them “right,” so all we can do is steer our way forward with our best judgement, tools, and bandmates.

And that sums up what we did and how we got here!

As the sole “continuous” founding member, your presence has been the enduring thread through Fairport Convention’s numerous lineup changes, which were once so frequent the band “could not keep the same lineup between two albums” (Harper, Colin. Meet on the Ledge: A History of Fairport Convention. Essential Works, 2000). You have also spoken of your early role providing a “background” for Richard Thompson’s “foreground” (Frame, Pete. The Restless Generation: How Rock Music Changed the Face of 1960s Britain. Omnibus Press, 2007). How has your personal musical identity and role within the band evolved and adapted over five decades, particularly as different strong musical personalities (e.g., Sandy Denny, Dave Swarbrick, Richard Thompson) have cycled through? What does it mean to be the “constant” in such a fluid, yet enduring, creative entity?

Not sure you’re right about the “continuous” adjective there. After the gig in Dublin’s National Stadium on December 4th, 1971, I put my tele back in its case for the final time in Fairport and made my long-planned exit, the last of the originals to leave the band. But as I say elsewhere, nobody ever leaves while they’re still this side of the greensward, and I kept in touch with my musical family through the next few years, going to gigs (once Sandy and I met at a Fairport gig in Cambridge and drank their dressing room dry while they were on stage) and even had a folk-club trio with Peggy and Swarb (The Three Desperate Mortgages) for laughs. Eventually, I was re-absorbed after engineering the project that became the ‘Gottle o’ Gear’ album, so I had a sabbatical. Dave Mattacks has come and gone more times than we can remember (four, actually. ed.), so Peggy has the record for longest continuous service. But of course, he wasn’t “original,” if that means anything.

Fairport Convention is remarkable for its sustained longevity and, as has been noted, a striking absence of the “rancour with former members” that often “bedevilled other bands” (Romero, Angel. “Fairport Convention: Still on the Ledge.” World Music Central, 2017). The band has been described as “a family in many ways,” with members spending more time together than with their immediate families. To what extent has this unique “family” dynamic, characterized by mutual respect and a deep, lasting bond (as captured by the saying “no-one gets out of Fairport alive”), been the primary determinant of the band’s ability to not only survive but thrive through tragedies, lineup changes, and industry shifts? How does this familial structure influence the creative process and decision-making within the band?

This question is almost the perfect definition of “rhetorical.” You have outlined the ethos that you have observed. Admittedly, it was not until the seventh LP was released that we managed to make two albums (‘Angel Delight’ and ‘Babbacombe Lee’) without adjusting the line-up in between(!), but we can now point to the fact we last took on a new member in the previous millennium (Chris Leslie in 1996, thirty years ago…). It’s true that, like the KGB, there are really no ex-members……

Fairport’s Cropredy Convention has evolved from a private reunion gig to one of the largest and most acclaimed folk gatherings globally, organized largely by the band itself. Concurrently, Fairport operates its own label, Woodworm Records, maintaining significant control over its output and finances. How do these self-sufficient models – the festival as a direct conduit to the audience and the independent label as a means of artistic and financial control – represent a deliberate philosophical choice for Fairport Convention, distinct from the traditional major label/celebrity paradigm? What are the long-term implications of this model for the band’s artistic freedom and its unique relationship with its fanbase?

When we were ditched by the mainstream music biz back in 1979, when Vertigo terminated our recording contract with four albums left, the biggest reason was the tide going out again after the tsunami of the whole Punk revolution across western culture of the previous four years. Everything old was in the skip, ourselves included. But happily, and perhaps not entirely coincidentally, other doors opened, and the iron grip of the megacompanies who dominated production and distribution of vinyl and tape “product” loosened, and it became possible for entities as small as bands themselves to manufacture and sell their own music. Similarly, the big West End agencies shed staff who were able to start up independently and act for not-dead-yet acts (and indeed to take on newbies with profiles too low to have been previously noticed).

All in all, it was a good thing, and we rode that wave with enthusiasm, piloted by Dave Pegg and his now ex-wife Christine, who had energy and sound business sense, and to whom all the credit for getting Fairport’s Cropredy Convention going and for turning it into the national institution it’s become since.

Fairport Convention’s work, particularly on albums like ‘Liege & Lief,’ is deeply rooted in story-based songs with a “narrative flow and a cinematic quality,” drawing from thousands of years of traditional material (Humphries, Patrick. Richard Thompson: Strange Affair — The Biography. Virgin Books, 1996). Even contemporary songs like ‘Over The Next Hill’ maintain this narrative focus, drawing parallels between journeys and life phases. How is the enduring power and relevance of narrative perceived in the folk tradition, and how has Fairport Convention consciously (or unconsciously) maintained this focus across different eras and lyrical themes? What role does this emphasis on storytelling play in connecting with audiences across generations, particularly in an increasingly fragmented cultural landscape?

Speaking for myself, narrative in a lyric is my go-to. The best songs are instantly visual, and sometimes read like a shooting script for a movie or the plot of a novel. And with a long song, I find I’m less likely to lose my way when singing it if I kind of watch the film when I’m singing. Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts remains beyond my grasp, however…..

Fairport Convention is renowned for its “mesmerising combination of acoustic and electric instruments,” a defining characteristic of British folk-rock (Irwin, Colin. The Rough Guide to English Folk. Rough Guides, 2004). It has also been noted that there has been an increasing focus on the acoustic world in recent touring. How has the band’s philosophy regarding the integration and balance of acoustic and electric instrumentation evolved over the decades, from the “searing electric guitar work” of ‘Liege & Lief’ to more recent “unplugged” approaches? What aesthetic and expressive qualities does each offer, and how are decisions made on the optimal blend for different songs or performance contexts?

Each incarnation of the band has played to its own strengths. And when people have left, I don’t think we’ve ever opted for a “looky-likey” replacement. Sometimes, as when Richard (Thompson) left the ‘Full House’ line-up, we simply hunkered down and split the money four ways instead of five!

In short, we deploy as best we can the musical forces at our disposal in the rehearsal room at the time. Everyone gets to play in their personal zone of comfort. And if we return to a song from an earlier era recorded by previous members, we interpret the music from our current POV rather than attempt mimicry.

The day Fairport becomes a tribute band to itself, I’m off!

Fairport Convention’s embrace of traditional British folk music, particularly post-1969, involved tapping into a rich heritage of material collected by musicologists like Cecil Sharp and Ralph Vaughan Williams. This re-engagement with ancient narratives and musical forms occurred during a period of significant social and cultural change in Britain. How is Fairport Convention’s role viewed, perhaps inadvertently, as cultural custodians or interpreters, connecting a rapidly modernizing Britain with its deep historical and mythological past? Are there specific instances where the band felt its music resonated with, or even helped shape, a broader sense of British identity or continuity during times of flux?

While you are correct in placing Fairport’s climb to our level of national recognition with some massive cultural shifts happening all over the world, and which affected all popular culture and political thinking.

What we achieved with ‘Liege & Lief,’ which has with hindsight become a bit of a watershed, was to put onto one LP the idea of blurring the division between “real” traditional song and contemporary writing by reshaping imagery and themes, and to show that folk tunes could fit in the setting of a sixties “beat combo”of electric guitars and drums. We’d already tinkered with this on the previous two albums since Sandy joined us directly from the folk clubs, but now with Swarb as a full member rather than a guest and the spur of rebuilding the band in a new image after the horrors of the motorway crash, we had a strong and unifying (so we thought!) project. But a new door was opened, and much music has since emerged through it.

Cropredy 2025 sold out in record time in a year where many festivals are struggling to survive. After decades of shepherding this event through changing times, shifting tastes, and now a turbulent cultural moment for live music, I wonder when you both step out onto that stage in August and look out at those fields, not just at the crowd but at the village, the boats on the canal, the campsite fires, the multigenerational families who have made it part of their lives, what runs through your minds?

I’m going to assume that we do indeed achieve our required sell-out and that the weather is in another perfect in-betweeny slot: not too hot, not windy, not too sunny, and definitely not too wet!

We get to hit the stage twice, as we play an opening “welcome” or introductory slot at 4pm on Thursday, and the four songs absolutely flash by. We’re seated almost cheek to cheek and using a single monitor send and acoustic instruments – it’s very real and “in the moment” and I always have to remind myself not to over-play and over-sing to the sea of (truly) beaming faces. A pinch-me moment I’m too busy to enjoy, really, as the idea is to make our point and leave the stage for the real opening act and for the Festival proper to begin.

Then on Saturday night, about 9:30, and as the last traces of the sun are fading out stage left behind Jonah’s Oak, our real business of the weekend gets underway. I’ll have been shut away in my caravan backstage for a good few hours, watching the clock creep slowly round and calming my butterflies, which only ever visit me this one time a year, going through what I might “spontaneously” say between songs. This again is unique to Cropredy, as I just rattle words out on normal gigs in what I hope sounds a conversational and natural way, but everything at Cropredy scale feels more significant and weighty.

So it’s a sense of final release when we get the all-clear from the stage crew and Anthony John Clarke can finally call us on to take our places and strike up the band for the final few thousand bars of another Festival.

Do you still feel you are curating a festival, or has Cropredy by now grown into something more intimate, almost like you are hosting a reunion for a kind of extended Fairport family?

Cropredy is far bigger than the sum of its parts and floats along on a deep river of shared and private affection and experience: and there is now a large community of individuals, couples, and families who have put down emotional roots in that postcode. I count myself among their number.

And more personally, as men who have poured lifetimes into this, what do you carry with you emotionally in that moment that perhaps your audience never sees?

Nobody can see how grateful I am for my luck in being part of it all, and for having been dealt the cards that I’ve played since 1967. And if that gratitude extends to quiet pride, I hope to be forgiven for that mild sin.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Simon Nicol | Fairport Convention at The Tung Auditorium in Liverpool 2025 (Credit: Alan Blundell Photography)

Fairport Convention Website