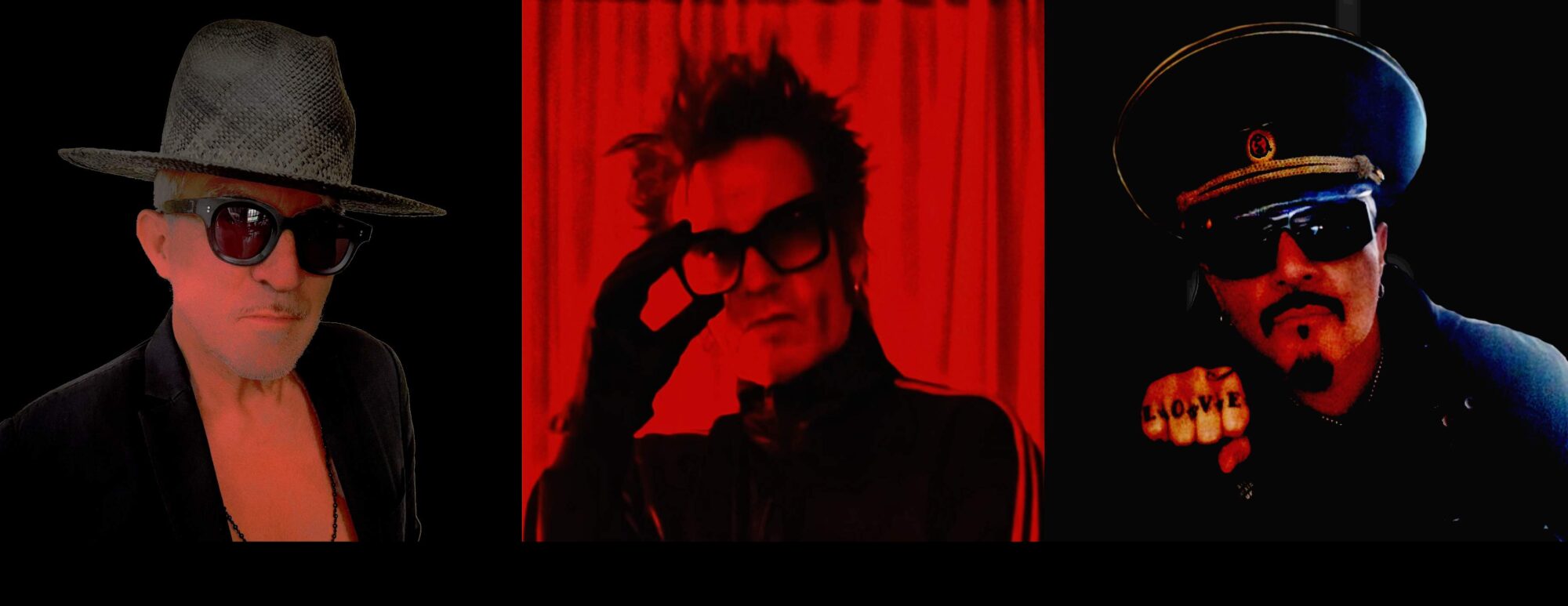

Ashes And Diamonds: Daniel Ash (Bauhaus) and Paul Spencer Denman (Sade) on working with Bruce Smith (PiL) and making Ashes And Diamonds Are Forever

Ashes And Diamonds brings together three musicians whose pasts sit in very different corners of British and transatlantic music, but whose instincts meet around groove, texture and restraint.

Daniel Ash carries decades of post-punk and art-pop history from Bauhaus, Tones on Tail and Love And Rockets, still working with the same sharp guitar language and the cut-up lyric method he has used since those early days, which he calls “extremely liberating.” Bruce Smith comes from the rhythmic experimentation of Public Image Ltd, The Pop Group and The Slits, and here mixes live drums with programming that keeps the tracks moving while adding an electronic haze. Paul Spencer Denman, best known for Sade and Sweetback, approaches the bass as both structure and melody, listening closely for space in the vocal and building foundations when the song needs stability.

Much of the album was written remotely, with Smith and Denman sending bass and drum ideas back and forth before passing them to Ash, who returned them with vocals, guitar and unexpected twists. Denman says he thinks about parts long before touching the instrument, often working them out in his head, and insists that every note has to justify itself. That attention to detail shows in how sparse some tracks are, while others pile up guitar, keys and effects without losing focus. Ash credits heavy use of E-Bow and layered keyboards for what he calls the album’s “cinematic” feel, while also stressing that keeping things clear often comes down to knowing what to remove.

There are flashes of confrontation, like the jagged sax on ‘Champagne Charlie,’ which Ash describes as a throwback way of creating unease, but the record is not built on shock. Instead it leans on momentum, atmosphere and melody, shaped by three players who know exactly when to push and when to leave space.

“As for everything not sounding a mess, that comes down to knowing what to take out. Less is more.”

The shift from the stark, sometimes intense sound of Bauhaus to the brighter, more psychedelic feel of Love and Rockets was pretty big. On ‘Ashes And Diamond,’ how do you map the vibe of the album through your guitar tone? And that jagged, manic sax in ‘Champagne Charlie,’ is that you reconnecting with the confrontational energy of your early stuff, or is it just a texture to throw listeners off a bit?

Daniel Ash: The jagged, manic saxophones used on ‘Champagne Charlie’ were a throwback idea that I’ve used in the past to convey a feeling of unease/madness. It’s just what was needed to convey what Charlie was going through. As for my guitar style/tone, I think it’s been consistent through the years.

Reworking your 2018 solo track ‘Alien Love’… beyond just adding heavy guitars, what did having Bruce and Paul involved bring out in the song that you didn’t hear before? Did their styles make you rethink the song’s core identity?

Daniel Ash: Paul had liked my original version but felt it was 80% there, so we had another crack at it, and the rest is history.

In a trio where your guitar usually dominates the harmonic and textural space, the notes mention sheets of guitar and keys on “ON.” How do you keep all that from getting messy? Do you see the keyboard as just filling in the space like an extension of your E-Bow textures, or is it a counterpoint that really takes the sound somewhere outside the guitar?

Daniel Ash: On this album I used a lot of E-Bow, hence the keyboard-heavy vibe. Bruce added additional keyboard textures also. Thinking about it, that could be why it all often sounds so cinematic. ‘Hello, Hollywood’—use our songs for your huge blockbuster films, thank you in advance. As for everything not sounding a mess, that comes down to knowing what to take out. Less is more, huge fan of that approach.

Q: The motorcycle theme pops up a lot—’Roll On, Motorcycle,’ ‘I Feel Speed,’ now ‘On a Rocka.’ Is it about pure freedom and speed, or is it more a metaphor for the relentless pace of modern life, which you then contrast with Paul’s unassuming melodic bass lines?

Daniel Ash: The motorcycle thing pops up a lot because I’m a total motorcycle nut. Always have been, so it’s bound to come up through the years.

Your lyrics are often super cinematic—“looking up at the Crystal Ship,” the red hot/white hot mantra. Do you focus more on the atmosphere of the words than a straight narrative? And how has your approach changed from the theatrical style of Bauhaus to the more direct, reflective vibe on “Hollywood”?

Daniel Ash: For lyrics I’ve always used the cut-up method, right from Bauhaus, Tones on Tail, Love and Rockets, and solo. Could not imagine starting a song any other way. It’s extremely liberating.

‘Teenage Robots’ is a classic three-minute pop song. Coming from an experimental background, what’s the creative payoff in nailing a traditional structure like that?

Daniel Ash: ‘Teenage Robots’ is a classic three-minute pop song. Music to my ears. Thank you.

Do you feel that the years of experience in your careers, distilled into this project, give ‘Ashes And Diamond’ a kind of weight or rarity that most new band debuts don’t have?

Daniel Ash: I think it’s inevitable that because we have collectively been involved in music-making for so long, we would have an advantage over someone just starting out.

Imagine we’re at my place, which is stacked with records and CDs from every corner of the world and every style you can think of. If you could pick anything to play, what records would you choose, and why that particular one? I’ll kick things off with ‘World Trade’ (1981) by Jeff & Jane Hudson.

Daniel Ash: The last question is so open-ended I have no idea what I would choose, as it’s always a mood thing when choosing what to put on. Knowing me, I’d probably prefer putting nothing on and enjoy the silence.

“I’m a slave to the song.”

On the track ‘A Listers,’ your bass lines are incredible and really take the lead. Do you think of them not just as holding down rhythm and harmony, but as their own melodic voice, like a quiet narrator watching and commenting on Daniel’s lyrics about the fake side of the entertainment world?

Paul Spencer Denman: In everything I’ve done, I listen acutely to what’s happening elsewhere with drums and vocals. It’s always my intention to provide a really solid foundation for the solo instruments—voice/guitar—to play on. Obviously I need a drummer who’s sympathetic to those ideals and understands me enough to realise these ideas. I could be a flea if I wanted to, but that wouldn’t be me. I’ve worked with a ton of incredible drummers, as Sade has no permanent drummer. Bruce is one of the best and most wonderful to play with. He plays great beats and does incredible programming. If any drummers are reading this, please listen to our album. It’s a Bruce masterclass in drums, rhythm, and percussion.

Your tone is always rich and smooth, which contrasts with the more jagged, brittle sounds a lot of post-punk bassists go for. When you joined Daniel and Bruce, did you have to tweak your instrument, your EQ, or the way you played to make sure your tone didn’t sound too polite or too smooth, especially on the more aggressive tracks?

Paul Spencer Denman: Obviously I come with my sound dialled in, so we had that. As the songs progressed, Bruce and I realised we needed more crunch. I spoke with Bruce, and so I started playing with a pick with more attack. I put a RAT (it’s a pedal) on my bass on the songs that needed it. Wasn’t really anything I haven’t done before—I came up through punk bands in the ’70s. Ultimately, I try to deliver what I think the song deserves. I’m a slave to the song.

“ON” is built around your simple but melodic bass lines. How do you think about that approach? Is the simplicity about restraint so the bass stays a solid foundation, or is the melody itself the key, where every note matters against the rest of the track?

Paul Spencer Denman: I think about what I play a lot. Most of my practice goes on in my head. I can play riffs and fuck around with them as images on the fretboard in my head and go from there. I literally do that every time I hear a song or advert on the TV. Playing with Sade, we tend to scrutinise every note, a bit like Dalí’s “Paranoiac-Critical” method, and so every note I play is important, as is the feel of how I am playing. I never try to over-complicate; I look for holes in the vocal for me to pop out on. If none are there, I will relentlessly build a foundation for vocal, guitar, keyboards, etc. But to do that perfectly, you need a world-class drummer, and Bruce is definitely that.

“ON” is actually a riff Daniel had initially. Bruce and I played around with it and arranged the song around that riff. Daniel is in a low register there, so I don’t want to play too much, but enough to fill out the vocal. I love what Bruce did on this track.

You come from Hull and have that history with Mick Ronson and the Spiders from Mars. Even though your technique is different, do you ever tap into that dramatic ’70s rock bass vibe when you’re building the foundation for tracks like ‘Boy or Girl’ and ‘Plastic Fantastic’…?

Paul Spencer Denman: What an influence the Spiders were. Michael and I lived on Greatfield Estate in Hull, and it was pretty rough! I was aware of him in his other bands before the Spiders. I am still very friendly with his sister Maggi—she’s wonderful.

I never got the chance to tell Trevor Bolder (RIP), but he really taught me how to play bass. I borrowed Ziggy from a friend, Charlie Haysom, at school, took it home, and played it till I could play along to everything Trevor played on the album. What people don’t realise is Trevor plays bass almost exclusively in a high register. There is hardly any deep playing. That’s why the songs sound light and poppy, even though Michael’s playing is rock-god style—Trevor’s isn’t. I play a lot of high register with Sade; there’s a bass solo on “Smooth Operator,” as an example, and it’s really because Trevor taught me not to be afraid of the high register. God bless you, Mr. Bassman.

On ‘Ice Queen,’ the mood drops and your bass really takes the lead, rumbling in a low gear. In a track meant to set a melancholy scene, is it meant to hint at deep unease, or just to give weight to Daniel’s twisted lyrics?

Paul Spencer Denman: We had the track before Daniel actually put lyrics to it. It came from the first session we did, as we rehearsed for the first time. I had that riff, which Bruce expanded on and put keys on, and then we sent it to Daniel, who wrote those amazing lyrics. It was a surprise to me, as it always is with Bruce and Daniel.

You come from the refined, sometimes syncopated world of UK R&B and smooth jazz, while Daniel and Bruce are rooted in fractured, funk-influenced post-punk. How did you and Bruce create a cohesive transatlantic rhythmic feel that worked for both the rock and roll side and the more cinematic side?

Paul Spencer Denman: It came pretty easy. Bruce is a very instinctive musician and an ideas machine, so he’s always ready to contribute. His programming work on this album is outstanding. I vibe off Bruce and he off me. We could have gone more R&R, but what we did was let the sound and mood come naturally. There aren’t any preconceived ideas with Ashes; it’s all from the heart.

We all would love to score a movie. It’s something we have talked and thought about a lot.

Since you often lay down the foundational groove, working remotely must have been different. Did you find yourself trying to guess what Daniel or Bruce might do, or did you wait until their guitar and vocal sketches were more complete so your bass could lock in perfectly with the final structure?

Paul Spencer Denman: Most of the songs came from a bass or drum idea Bruce and I might have. I wrote ’47 ideas for Ashes,’ whittled them down to 24, and sent them all to Bruce, who would chop them up and put beats and percussion to them. We sent stems back and forth to each other until we had something we liked, and then sent it to Daniel. We never knew what Daniel would do till the track came back. We only knew one thing, and that was Daniel would come up with something totally unexpected.

On ‘Setting Yourself Up for Love,’ which is a real thing of beauty, your bass lines and Daniel’s vocals have to work together. Do you try to follow the rhythm and emotion of the vocals, or do you prefer the bass to be its own voice, providing a stable counter-melody?

Paul Spencer Denman: It depends on the song. For ‘Setting,’ it was really obvious that I needed to be aggressive to complement Daniel’s aggressive vocal. I thought from the beginning that one note would do for this—and it did.

Having played with big artists who fill huge sonic spaces, is there a particular freedom in a power trio like Ashes And Diamond, where the bass can move and breathe and be clearly heard as a central part of the arrangement?

Paul Spencer Denman: No. I approached this, as I always do, with an open mind. There are no rules, and we must listen to each other and respect what is going on with the song and complement the vocal. It’s something I learned very early on from Sade producer Mike Pela (RIP) and Robin Millar. They taught me so much, and that’s really when I honed my skills on the first two Sade albums. Robin and Mike were very hard taskmasters and wouldn’t let me get away with anything. If I heard “No, that’s not good enough” or “Not listening, Paul—where is the fuckin’ kick?!” from Robin, I heard it 100 times. I owe them both big time.

Imagine we’re at my place, which is stacked with records and CDs from every corner of the world and every style you can think of. If you could pick anything to play, what records would you choose, and why that particular one? I’ll kick things off with ‘World Trade’ (1981) by Jeff & Jane Hudson.

Paul Spencer Denman: Oh my… that is tough. My two favourite genres are punk and Tamla. So……

‘Anarchy in the U.K.’ and ‘God Save the Queen’ — Sex Pistols (life-changing; I would not be here now if it wasn’t for the Sex Pistols)

‘Ziggy Stardust’ (Trevor Bolder at his super-duper upper-register best)

‘I Want You Back’ — Jackson 5 (bass by Wilton Felder, probably the greatest bass line of all time)

‘Band of Gold’ — Freda Payne (bass by Bob Babbitt, incredible player, often mistaken for and equally as good as Jamerson)

‘What’s Going On’ — Marvin Gaye (Jamerson at his drunken best)

‘To Each’ — A Certain Ratio (game-changer for me, made me expand my mind—fuckin’ brilliant and totally underrated)

That’s a few, and there will be a few more when and after I submit this! Catch up with me when the next Sade album comes out and I’ll line up a few more for ya.

Enjoyed this immensely. You’re a cool dude.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Ashes And Diamonds – L to R: Bruce Smith (photo credit: Chelsea Miller), Daniel Ash (photo credit: Regan Catam), Paul Spencer Denman (photo credit: Stuart Matthewman)

Ashes And Diamonds Website / Facebook / Instagram