Buzzard Interview: Bob Dylan, Black Sabbath, and the End of the World

Buzzard operates in the fertile borderlands where acoustic confession meets doomed amplification, a self-described realm that’s “too folk to be metal and too metal to be folk.”

The project’s creator frames it more bluntly: “What if Bob Dylan listened to Black Sabbath and read H.P. Lovecraft?” It’s a neat summary of music that pairs fingerpicked balladry with riffs indebted to Candlemass and Electric Wizard, all in service of narratives populated by witches, zombies, cosmic entities, and the everyday cruelty of modern life.

Origin stories matter in underground mythologies, and Buzzard’s is suitably funereal. The spark came from “a photo… of a buzzard on a cross in a Cleveland cemetery,” which became a joke album cover, then a logo, and finally the catalyst for writing songs that had “felt too weird and dark for the folk world of coffeehouses.” What followed was not genre tourism but an organic escalation: “doom folk did not come out of nowhere.”

Despite the theatrical extremity, the songs begin in intimacy. “All the songs on Doom Folk were written on acoustic guitar,” later dragged into distortion, sometimes literally, as heavy tones were born from acoustics run through crude fuzz plugins. Lyrically, Buzzard balances satire and sincerity, wielding gallows humour as both scalpel and shield: “I’m not interested in po-faced gloominess or proselytizing… that’s boring and sanctimonious.”

It’s protest music for the end times!!

“What if Bob Dylan listened to Black Sabbath and read H.P. Lovecraft?”

You’ve cooked up this crazy brew of music. When you first heard the finished track, say, ‘Lucifer Rise,’ what was the internal argument you had with yourself about what the heck to actually call this sound?

First off, thank you for all these great questions. I’ll try to do them justice.

The phrase doom folk came naturally and stuck easily. Long before ‘Lucifer Rise,’ my music had been getting darker, with more tritones and minor keys. For many years prior to Buzzard, the promo phrase for my duo with my partner Lisa, Austin & Elliott, was that we sang songs about “love gone wrong and death done right.” So, this music evolved into doom folk organically over the years.

But there was a tipping point for the birth of Buzzard. In 2019, a friend’s brother-in-law in Ohio shared a photo he took of a buzzard on a cross in a Cleveland cemetery. A couple of friends and I joked about how it would be the perfect doom album cover. One of us (Andrew, aka Colossal Squid Design) created a logo for a fictional band called Buzzard. Then I created the purple ‘Doom Folk’ album cover in Photoshop, at which point I figured, well, the only thing missing now is the music, so I started writing and recording songs, beginning with, naturally, ‘Buzzard,’ which practically wrote itself.

As I wrote more Buzzard songs, I combed through my archives for the songs that had felt too weird and dark for the folk world of coffeehouses, like ‘Lucifer Rise,’ which had been kicking around for a couple years. ‘Death Metal in America’ was written in reaction to the 2016 US election, and ‘Cockroaches and Weed’ was inspired by Electric Wizard riffs around 2012; original versions of both appear on ‘Satiricus Doomicus Americus,’ another project which I did not know what to do with.

Like I said, doom folk did not come out of nowhere. For instance, Austin & Elliott often performed a song about Ed Wood, which audiences seemed to find alternately befuddling and amusing. We also had ‘Rocking the Cradle,’ which steals the riff from ‘Electric Funeral,’ and ‘Blackwater Dam,’ which culminates with—spoiler alert—the entire world drowning. As far back as ten years, the notion of doom folk was percolating; but it wasn’t until the buzzard photo that I found the key to unlock the vision. That’s when I went doom folk whole hog.

The elevator pitch “What if Bob Dylan listened to Black Sabbath and read H.P. Lovecraft?” popped into my mind while I was working on ‘Gods of Death.’ The chord progression is based on ‘Bewitched’ by Candlemass and arrangements influenced by Celtic Frost ‘Innocence and Wrath.’ The chorus is inspired by the famous Lovecraft line, “That is not dead which can eternal lie, and with strange aeons even death may die.”

Every track is a tug-of-war between that intimate, acoustic vibe and the massive, fuzzed-out heaviness. Do you always start a new song on the banjo or an acoustic guitar?

All the songs on ‘Doom Folk’ were written on acoustic guitar. Through the recording process, I added, subtracted, and toyed with fuzz guitar, banjo, bass, hand drum, and harmonies. The songs, at their core, are acoustic solo songs which I can sit down and perform in a room unaccompanied. To quote Bill Hicks, I am available for children’s parties.

In terms of fuzz, the heavy guitar is actually an acoustic run through a rudimentary distortion plug-in. I did not own an electric guitar at the time. The heavy songs on Mean Bone are among the first songs I’ve ever written on an electric guitar. A few, like ‘Changeling,’ I can sit down and perform unaccompanied. I am also available for baby showers.

The banjo is, in fact, not a banjo, but a primitive 6-string “banjitar” in standard tuning that Lisa had bought 20 years ago in a record store. I’ll write for but not on the banjo. The ancient steel strings of my banjitar are agonizingly difficult to play, especially any chord except D minor (which, not coincidentally, is the key of most Buzzard banjo songs, for those playing along at home). I don’t sit down and write songs on the banjitar itself because I’d end up with bloody stumps for fingers, but I have written songs on guitar with the banjo/doom riff sound in mind, like ‘Buzzard’ and ‘Dunwich Farm.’

I appreciate your phrase “tug-of-war,” as the sound in my head is one that is “too folk to be metal and too metal to be folk.” This tension is what I find interesting and exciting, a template within which I can express virtually any lyrical idea, no matter how weird, earnest, silly, morbid, vulnerable, or confrontational.

Your stuff sounds like it’s straight out of a shadowy, old cabin in the woods. Dark Americana and something truly unholy. Is there something about the atmosphere or the weird history of Western Massachusetts that you think naturally creeps into and darkens the songwriting?

Rural New England certainly boasts its share of creepy woods, mossy graveyards, and dilapidated farmhouses. The winters are beautifully bleak. It’s easy to imagine the ghosts of Puritan witchfinders stalking the blackberry bushes.

I’m not from Western Mass originally. I grew up fairly isolated as an only child in upstate New York. My house was three miles from the shopping mall but a mile past the town line where the cable TV stopped running. Lots of time to stare up and aim my flashlight up into the starry sky, imagining where the light might travel.

On the one hand, it was a secure, middle-class existence with an IBM dad and Star Wars toys for Christmas. On the other hand, we had sixteen woody acres for me to wander alone unsupervised and a barn full of chickens which a couple times a year I’d help kill and dress for dinner.

Where I live now in Mass is a mix of college town and hilltown. By day you’ve got your cafes, bookstores, and quaint shops. At night, you can hear the hoots of owls and howls of coyotes. Besides my basement studio, my favorite place is the little dilapidated backyard barn where we store firewood and I can daydream, listen to weird fiction audiobooks, and smoke the occasional cigar.

While all of the above atmospherics creep into the songwriting, as you say, I also think it’s temperamental. A dash of sarcastic humor and on-the-spectrum-ness runs on my dad’s side of the family. As an only child, I spent a lot of time reading, drawing, and writing words by myself. As a bonus, I was bullied a bit at school, so my relationship with society may have soured early on, shall we say.

The final thing I’d say is that more than physical environment, it’s my music listening environment that shapes my songwriting: Candlemass, Blind Willie Johnson, Zeal and Ardor, Townes Van Zandt, Cattle Decapitation. I live more in my head than I do the outside world.

Your lyrics are packed with pitch-black wit and that classic Bill Hicks/George Carlin-level social critique, especially when you’re tackling big themes like religion and political madness. Is that dark humor a vital tool for you, maybe a way to keep from drowning in the heavy themes, or is it just how you naturally talk?

Both, for sure. Gallows humor, like the dead baby jokes of Anthony Jeselnik, is a tool to cope with the horrors of the world. My experience writing songs is one of savage fun and personal catharsis. I’m not interested in po-faced gloominess or proselytizing. That’s boring and sanctimonious. I appreciate it when listeners latch onto the satirical humor in Buzzard. Lines from Mitch Hedberg, Mr. Show, and Bill Hicks live rent-free in my head and appear in my everyday conversation whether people get it or not.

I’m just writing about the things I’m already thinking and talking about, whether big themes like political strife, climate change, and religion or fun stuff like insects, zombies, death metal, Satan.

Dark humor, clearly integral to my personality. The first, very dumb, song I ever wrote as a kid was ‘The Milk Truck Ran Over My Pig,’ an absurdist lament with zero substance except silly morbid humor. Another very early song was ‘Bananas and Bombs,’ which described a society of monkeys that become paranoid about shadows in the jungle, so they start turning their bananas into bombs to defend themselves from an imaginary enemy while they go hungry. So, yeah, I think I was just born this way. (Note: both of those songs are terrible pieces of juvenilia and you will never hear them.)

In my 20s I sang ‘Heavy Metal Daze,’ a humorous ode to teenage drinking that ends with a kumbaya-style singalong of ‘You Shook Me All Long.’ On the non-funny dark side, I had ‘Cinderella’s Midnight Surprise,’ an epic tale in which she goes on a quest to find a soldier who has a gun that fits a bullet given to her by her father (spoiler alert, everybody dies in the end). So you see, the ingredients of doom folk metal have always been in my music.

One thing you say is interesting—“is it just how you naturally talk?” I think all writers should, in a sense, try to write the way they talk. Your writing and speaking voice should have the same personality and concerns. It’s like your writing voice is a refined version of your speaking voice, similar but better, you hope—smarter, funnier, and more eloquent than when you speak extemporaneously.

If you don’t sound like you when you write, then who the heck who?

You play, write, and produce all of this yourself. What’s the single most unexpected freedom you gained from locking yourself in the basement and being the only one calling the shots? And what do you miss most about the days of actually jamming a new riff out with other people?

I don’t miss those jamming days because I never had them, ha ha. I’ve always been a solo enterprise, except when working with my partner Lisa as Austin & Elliott. Decades ago, I had a couple short-lived bands with friends where I was the sole songwriter. We collaborated on arrangements and I took song feedback “under advisement,” ha ha, but we did not jam.

To borrow the phrase that describes 60s troubadours, I am “a lone guitar and a point of view.” Now I’m a lone one-man doom folk metal band with a point of view.

To be honest, I don’t jam well. I’m not good at collaborating. I’m a limited player and writer. It’s not that I’m a control freak who insists on calling the shots, it’s just that I’m somewhat constrained by my specific sensibility and clumsy fingers. My knowledge of music theory is more than zero but scattershot, strictly on a need-to-know basis. I am somewhat envious of my friends who master their instruments, collaborate with friends, and tour with bands. It sounds like fun!

But what’s more fun for me is constructing my own musical universe alone. With a home studio, I can experiment instrumentally, vocally, and lyrically with no fear of judgment from a watchful engineer or bandmate. I enjoy the freedom to fail and fail again until I get things right.

If you had to name a more low-key, cult-favorite source for your writing—maybe a forgotten B-movie, a pulp novel, or a piece of local folklore, what would it be and how did it sneak its way onto the record?

Easter eggs from metal, folk, comedy, and literature find their way into my lyrics, on a line-by-line basis. It’s so hard to pick one.

In recent years I’ve been immersed in the weird fiction world of writers like Thomas Ligotti and publishing imprints like Chiroptera/Cadabra, Valancourt, and Hippocampus. The bleak cosmic nihilism of this literary niche creeps into songs like ‘Necro Tech.’

Ground zero for my satirical horror sensibility are the shopping mall scenes in Romero’s ‘Dawn of the Dead.’ Any song where horror or science fiction tropes convey social criticism, there’s Romero.

When I was a kid I saw the obscure ‘Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things’ one Sunday afternoon at my grandparents’ house, and that night I had one of the most truly terrifying nightmares of my life. I still chase that thrill.

Not so obscure, obviously ‘Dunwich Farm’ from Mean Bone is the result of Lovecraft’s ‘Dunwich Horror’ colliding with Bob Dylan’s ‘Maggie’s Farm.’

Though I grew up reading Lovecraft and Stephen King, it wasn’t until recently that I discovered the EC Comics library of horror and science fiction tales like the original Tales from the Crypt and Haunt of Fear, which are full of social commentary. Their revenge yarns influence the grim twist endings in my songs. Poetic justice is a dish best served with steaming entrails.

Besides books and music, so many moments from everyday life sneak into my lyrics. For instance, a line in ‘Death Metal in America’ tips a hat to the time I saw Amon Amarth in Boston, and the singer did stage banter in his Cookie Monster voice, growling at the crowd, ‘So… how about them Bruins?’

Your lyrics are brilliantly visual and absolutely crammed with these memorable, bizarre characters. Do these characters like the ‘Stoner Cockroaches’ start as metaphors, or do you have a full, weird, short story brewing for each of them before they even become a song?

Generally, a song starts with an image, phrase, or scenario. Metaphor and meaning, if they come at all, come later. A song has to work on a surface level (marriage of melody, lyric, and instrumentation) before it can work on a deeper level.

For example, ‘Lowdown Dirty Hungry’ started with me imagining various alien and zombie scenarios, which is only natural. Then I got the idea of vegetarian aliens discovering and being corrupted by humanity’s legacy of eating meat. This also is natural, as Lisa is 100% vegan and used to work in animal welfare, and I’m almost 100% vegan and I care deeply about animal rights. The song doesn’t begin with the polemical point but arrives there later. The zombies and aliens make it fun, the dogs make it disturbing, and the meaning makes me care about crafting it and getting it right.

‘Cockroaches and Weed’ began with the jokey, not entirely original notion that the only form of life that would survive nuclear war is cockroaches and… hmmm… how about also weed, which is literally a weed. What next? Well, the cockroaches would smoke the weed. What next? They’ll evolve. OK, what might that look like? They would become peace-loving sages. What does this look like? Antennae spreading seeds, global ganja farms, and hippie spaceships. They would wear wizard robes for no other reason than I was listening to Electric Wizard at the time. The story has a happy ending, as humanity is replaced by a more advanced civilization that will spread enlightenment throughout the galaxy rather than build SpaceX shopping malls on Mars. It’s all perfectly logical, don’t you see?

This music is intense and deeply personal. Do you have any specific ritual you use to get into the right headspace before you hit the record button? Do you need silence, a specific drink, or maybe something else?

I dim the lights and go. The luxury of having a home studio is I record whenever I want. My microphone is set up ready to record 24/7. The cables haven’t been unplugged or untangled in years.

I have no patience for rituals. The mood to sing or strum strikes and I go. In fact, once in the mood, I may stay fired up and focused for days on end. Alternatively, I may feel vaguely uninspired but restless, so I hit the record button, and the first couple takes serve as the ritual that immerses me in the world of the song I’m working on.

I can’t imagine going back to the days of standing in a booth for $100 an hour trying to force the mood. In such a scenario, I pace nervously and try breathing exercises to prepare.

I live and breathe these songs, pondering and revising words ceaselessly. Sometimes I’m writing the song as I’m singing, discovering the voice of the narrator and refining the language as I listen back, trying different turns of phrase, intonations, and word choices. Usually, when I hit the record button, I have already got some piece of the song inside me burning to get out.

The one thing I value above all else is solitude. I feel too self-conscious if anybody can hear me singing. I make sure the door is closed and Lisa is either not home or not near enough to eavesdrop. Often I’ll hurry home from work to belt out a song before Lisa gets home.

Come on, you’ve gotta have one. What’s a lyric or even an entire verse you wrote that was either too dark, too funny, or just too personal that you had to cut from the album? We promise not to tell anyone… much.

Such an interesting question, to which I can offer various versions of yes and no. I revise relentlessly, so I have endless pages of discarded, jumbled, and experimental lines cut for a host of artistic reasons, from darkness to dorkiness. The world sees just a fraction of the verbiage I pump out.

Lately I’m drawn to the artistic challenge of expressing a dark thought in a phrase so felicitous that the listener cannot help but nod along, like how a dark joke leverages the tension of uncomfortable subject matter into laughter.

So, no, I never cut lyrics for being too dark, but for being artless. Let it be dark and demented, as long as it rhymes.

That means I can’t offer you a censored final verse of ‘Gods of Death’ where the singer summons the gods of Olympus to break into the Vatican and… OK, let’s stop there.

However, I can also answer yes in the sense that every lyric is crafted to walk a line between, say, doomsday preacher and relatable everyman. I may strike a balance between gleeful nihilism and principled protest. For instance, the singer in ‘Lord of Darkness’ does “pledge allegiance to the grave,” which is weird and fucked up, but to avenge slaves, which suggests a righteous moral code.

Imagine writing ‘Lucifer Rise.’ The singer summons Lucifer. Why? To kill his enemies, among other reasons. How do I convey that idea while rhyming with “rise”? I could say “to take my opponents’ lives,” but that’s just a lame way to put it. I could say “to gouge out my opponents’ eyes,” which is more exciting, but maybe too gory, detracting from the atmosphere. Ultimately, I arrived at “to slay my opponents with a thousand knives,” which strikes me as the right tone of invocation—the language is more elevated, almost Biblical, with the naming of the number, the concreteness of knives, the mythological feel of a verb like “slay.” The line is no less dark, just more deliberate.

But you’re asking this question to get something juicier, so I’ll deliver.

I do have murder ballads in the vault where I haven’t quite found the right musical arrangement or language to depict the violence entertainingly but artfully. My best/worst is “Seven Gypsy Singers,” in which a jealous maniac one by one murders seven suitors who serenade his beloved. He does so in cartoonish ways that match each of their clichéd vows of love. For instance, when the first suitor sings to the beloved, “I’ll give you my heart,” the singer attacks and rips open his ribcage with an ax; another suitor promises to swim across the sea for her, so the narrator throws him in the well to drown, and so on. I’m reading the lyrics now and they’re utterly demented. Sample lyric: “Number three sang to her, ‘You’re always on my mind.’ / So I swung a board, and oh my Lord his gourd split open wide / The fourth one said, ‘I will sing the most melodious note’ / I wrapped a rope around his throat and said, ‘Oh no, you won’t.’” The punchline to the song is that after his gory murder spree, the psychopath turns to the presumably terrified object of his affection and sings:

At last I turned to my true love to sing this serenade

Saying, “Darling, tell me why do you look so afraid?”

Not all lyrics of mine land on the cutting floor because they’re so deranged. I have plenty of earnest, literal, normal-person lyrics that aren’t ready for prime time because they come across as diary entry. For example, the theme of bullying pops up in Buzzard songs. I do have confessional lyrics in my files that address my personal experiences being bullied in a vulnerable way. Those I’m not sharing quite yet.

Let me add one last drop of juiciness. If you think these songs are dark, wait until you see what I have in store for future albums: homicidal constellations of stars, a necrophilic sorceress, a suicidal fetus.

In other words, safe to say I won’t be moving to Nashville and co-writing songs for Morgan Wallen any time soon.

I would love it if you could discuss some further details about ‘doom folk’ issued by Herby Records?

It exists 100% thanks to Frank and Justin at Herby. When I first put out ‘Doom Folk’ on Bandcamp in March 2024, after three years of tweaking, dithering, and building up the courage, I had zero marketing or physical media plan except to email a couple blogs and, most likely, watch the album sink into the indifferent void.

But once I got some positive feedback, I felt encouraged to start working harder at promoting. As an avid record collector, I dreamed of having my music on vinyl, so when Herby reached out on Instagram last year out of the blue, I was thrilled. I sent them 24-bit files and they took care of the rest. Justin translated my original cover concept into a gorgeous record sleeve. I had final word on everything, but there was minimal need for me to give feedback—they were on point and professional every step of the way.

Since then, I’ve collected several Herby releases. As a record guy myself, I can attest these are beautiful productions. I won’t be surprised if they become legendary items discussed in hushed whispers by collectors decades hence.

What about ‘Satiricus Doomicus Americus’ and ‘Mean Bone’? Can you talk about those as well?

‘Mean Bone’ began in the fall of 2023, when I bought some drum programming software and an Ibanez electric. Whereas ‘Doom Folk’ began as acoustic folk with metal mixed in, Mean Bone began as doom metal with acoustic folk mixed in.

With ‘Mean Bone,’ my ambition was to define a template of what heavy doom folk can be, especially from a songwriting perspective. I tried including different songwriting forms, like a murder ballad told in dialogue (‘Murder in the White Barn’) and a third-person historical narrative (‘Flies, Mosquitoes, Rats, and Sparrows’). Admittedly, the record may be a bit too long, but I was trying to squeeze in every angle, every approach to riffing, fingerpicking, arrangement, structure, theme I could imagine within my abilities.

The theme is wickedness, the “mean bone” in our species, manifested in zealotry, psychopathy, greed, cruelty, ignorance, short-sightedness, and so on. The album begins with an apocalyptic prophecy (‘Darkness Wins’), and this prophecy is fulfilled in the final track (‘Ancient Ruins of the 21st Century’) where we see, indeed, darkness has won.

The songs on ‘Satiricus…’ go all the way back to when I bought my home studio in 2008. ‘Nice Little Annihilation Song’ is the first song I ever made that used sampling, overdubbing, and doom-folky vibes in a band arrangement. The samples come from vintage commercials, public domain movies, and Depression-era blues records.

My hard drives must have 100 different mixes of these songs as I experimented obsessively with different arrangements and samples. The versions I released may not even be the best, who knows, but they satisfied me at a moment when it felt right to release them, in the year of our lord 2025, with everything in the world going so swimmingly.

Two Satiricus… songs are recent: the title track and ‘Shuffle of the Dead.’ In fact, these two could have wound up as Buzzard songs, but I envision Buzzard as a sample-free zone. The phrase Satiricus Doomicus Americus felt like the perfect title for the whole project.

If you play the two different ‘Satiricus’ and Buzzard versions of ‘Cockroaches…’ and ‘Death Metal…’ back to back, you might get a sense of how I hear the difference between the two projects, with the former more organic and raw, and the latter more ironic and layered.

Since your albums are so layered and produced on your own, what’s the biggest challenge when you have to take these songs out of the basement and perform them live? Do you have a rotating cast of friends helping out, or is the live show a completely different kind of stripped-down, hypnotic ritual?

I’ve yet to perform Buzzard live. My hope is to perform the acoustic songs either solo or with Lisa on hand drum and harmony. My live performing style is clear and direct, not loose and jammy. I lean forward in a battle stance and enunciate every word.

Eventually I’d love to put together a band. Musically, it would be a tight ship focused on the songs, not jammy and vibey. To complement the music, I imagine projecting films similar to the lyric videos on YouTube for ‘Witches Revenge,’ ‘Darkness Wins,’ and ‘Ancient Ruins of the 21st Century,’ among other pre-Buzzard solo songs like ‘Shostakovich Kept a Toothbrush’ and ‘Sorry State.’ Not whole films, but rather tightly edited from multiple sources to go along with the songs.

I’m ready and willing to march onstage and bang out ‘Gods of Death’ and ‘Cockroaches and Weed’ with my six-string. Like I said, I am available for weddings. Maybe I can tour nursing homes to cheer up the residents.

What’s next for you?

Ho boy, do I have a lot more Buzzard for y’all.

The late-2025 7-song ‘Everything Is Not Going To Be Alright’ dives into politics headfirst. My elevator pitch is “Woody Guthrie has risen from the grave, and he’s pissed.” Protest songs like ‘Fever Breaks’ are personal too, as my day job involves teaching English to immigrants and refugees.

The next LP ‘Hush Now’ is 99% done and ready for release early 2026. I’m extremely excited and proud of the 12-song cycle, which incorporates elements from all the preceding releases while exploring classic keyboard sounds like Mellotron.

Another LP ‘Cosmic Conspiracy’ is also nearly done. This is the heaviest one musically. The lyrics focus on the Lovecraftian part of the Buzzard equation, with tales of aliens, space birds, and hostile deities. Not sure of my elevator pitch yet—maybe “Thomas Ligotti started a metal band, and the entire universe hates you.”

I’m about halfway through an animal rights EP where every song depicts a rebellion of animals against humanity. I’m also working on an acoustic LP that shows the softer, more personal, almost, gasp, “normal,” side of my Buzzard persona.

By the time I finish and release all this music, I’m sure I will have worn out my welcome.

Thanks for incredibly thoughtful questions and the opportunity to wax in response.

Klemen Breznikar

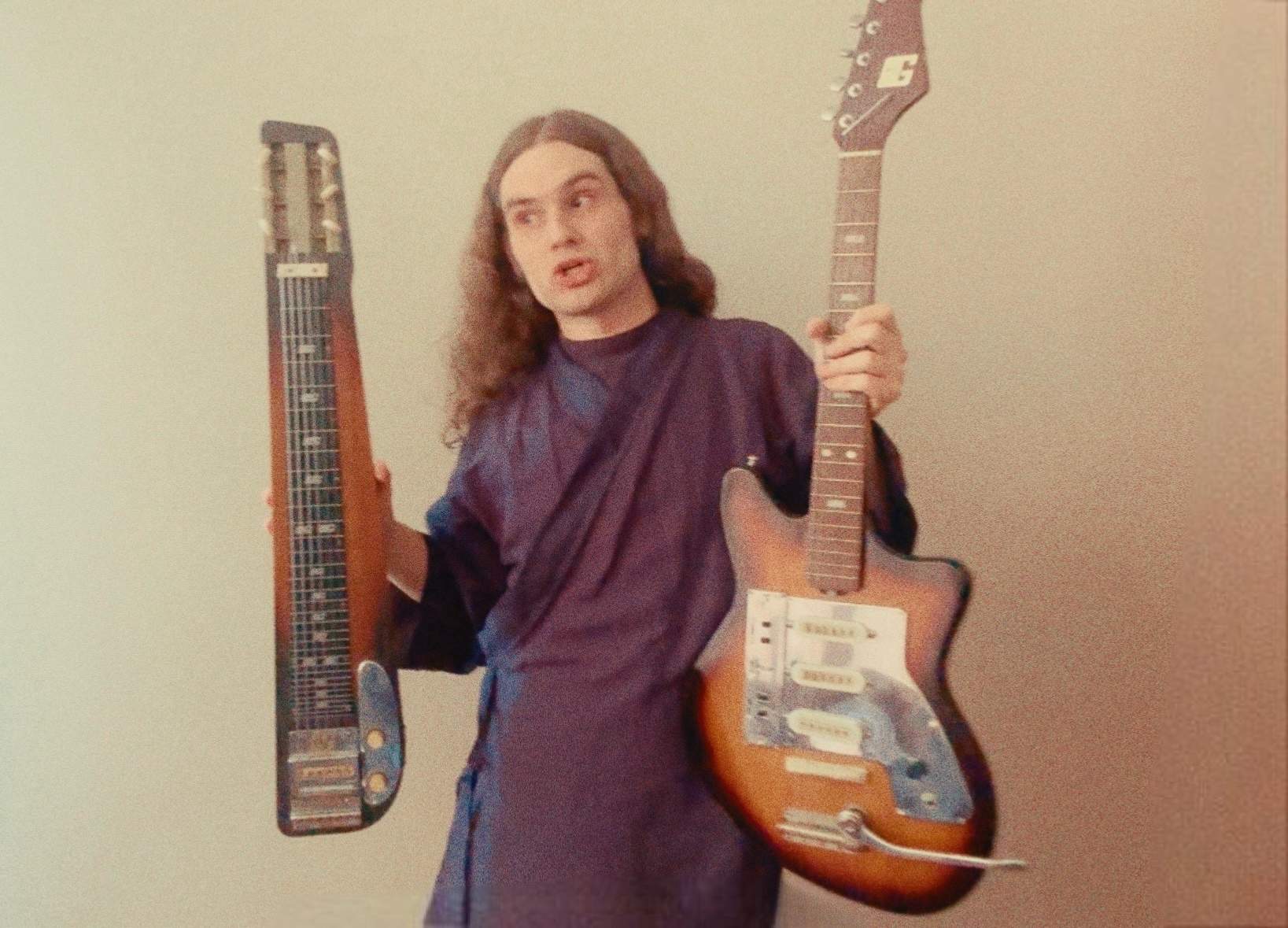

Headline photo: Buzzard in the Barn (Credit: Christopher Thomas Elliott)

Buzzard Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp / YouTube

Herby Records Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp