Descendents’ Milo Aukerman Reflects on ‘Milo Goes to College’ Ahead of Extensive Reissue Campaign

Few bands have worn adolescence on their sleeves quite like Descendents. Back in 1982, Milo Aukerman, Bill Stevenson, and the rest of the crew captured the jittery energy of high school frustration and spilled it across ‘Milo Goes to College,’ an album that still rattles speakers forty years later.

The songs perfectly captures that mix of teenage frustration and nervous humor, from the spitfire riffs to Aukerman’s earnest, almost nerdy vocals. Their songs hit like soda bottles thrown against a brick wall, fizzing with panic and glee at the same time.

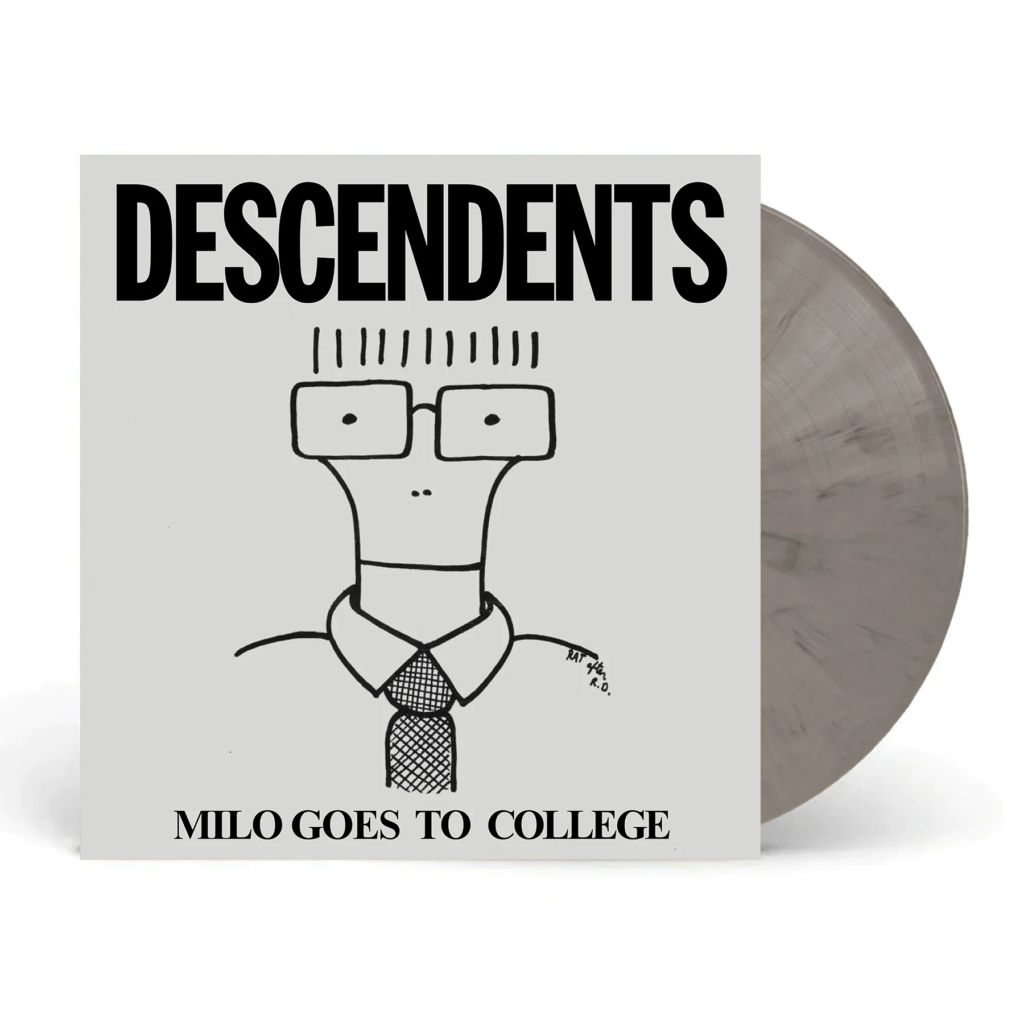

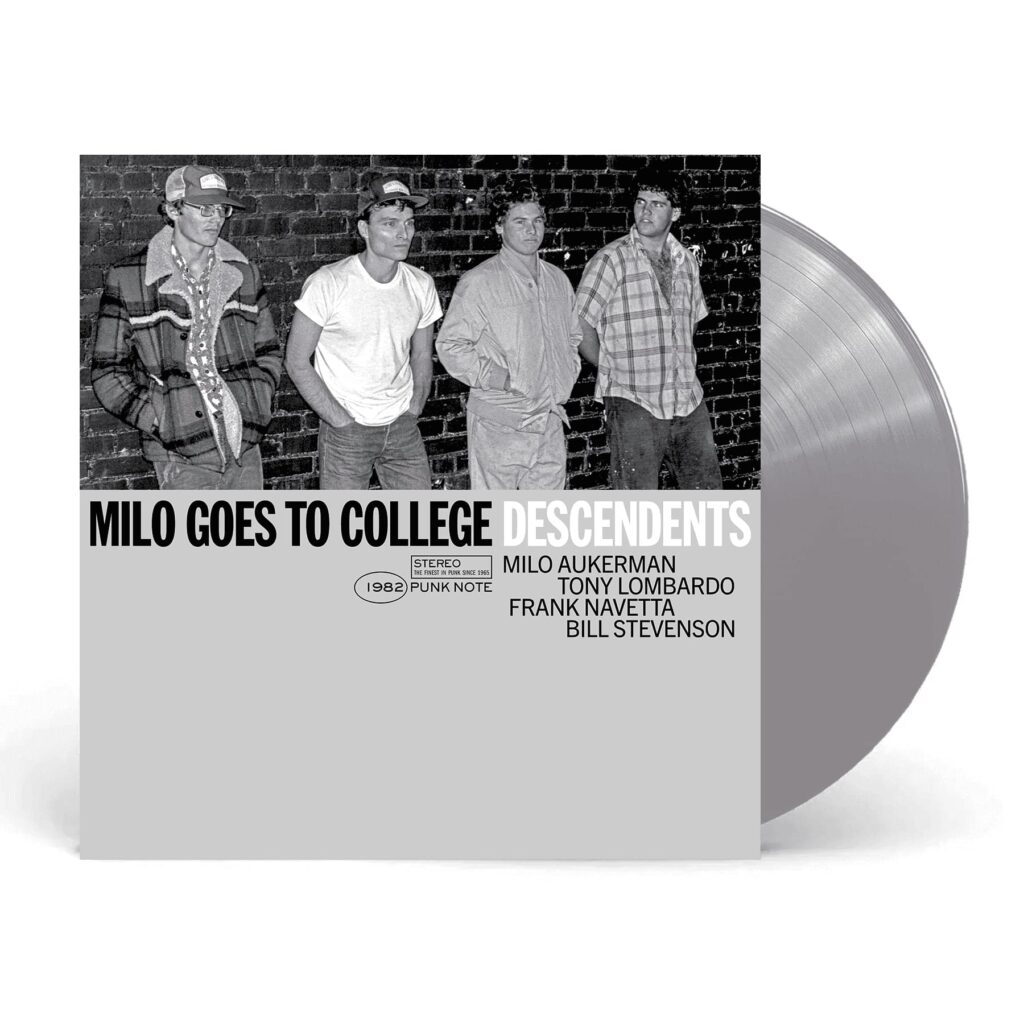

Now, Org Music is resurrecting that classic in a full reissue, available on LP, CD, and cassette from September 19th. Vinyl freaks and longtime fans will delight in the new Punk Note editions, which recast the album’s look with a wink to Blue Note. Rare color variants and exclusive pressings give each copy its own personality, echoing the way the songs themselves refuse to be neat.

Definitely a lot more than nostalgia… Reclaiming the original recordings allows the band to present their work exactly as they always imagined; the re-issue of ‘Milo Goes to College’ is a dream come true for all of us music, film, and general geeks.

Pre-orders and variant details available here: and here!

“We were frustrated teens when this music was written”

I bet ‘Milo Goes to College’ still feels like it was just yesterday, but here we are, decades later, reissuing it with real intention: to preserve it with care and baptize a new generation of punks. The band’s influence is undeniable, but here’s the thing: what’s one moment, whether it’s a lyric, a sonic twitch, or a stuttered breath between choruses, that you think got lost in the noise or is often overlooked or misunderstood? And what do you hope some 17-year-old kid in 2025 hears in it that cracks their ribs open the way it cracked yours?

Milo Aukerman: We were frustrated teens when this music was written; you might even call us incels back then, but harmless ones. Still, certain lyrics have become uncomfortable to sing these days, like in ‘Hope’ where I say, “I’ll have my way, you won’t have a say anyway, I’ve got you. You don’t stand a chance.” I interpret that as my fantasy of being in control in a relationship, but it’s over-the-top enough to be toxic, at least I view it that way now. So I sing something different live now. That’s my right as the songwriter!

The alternate “Punk Note” edition is a stunning homage to the design of the Blue Note jazz label. What’s the connection for you between the two genres? While they seem a world apart on the surface, what do you see as the shared spirit or philosophy between the raw, fast-paced intensity of hardcore and the intricate world of jazz? Is it freedom to do what the hell you want?

Bill [Stevenson] is a big jazz fan, and when Stephen [Egerton] joined the band, they geeked out on the Mahavishnu Band together. This led to a jazzier Descendents for a time (‘Iceman,’ ‘Schizophrenia’). I do think the “no rules” philosophy that punk shares with jazz helped punk expand beyond its roots in simple 50s rock and roll. Hopefully, we stay true to “no rules” and keep punk evolving. Aside from that, the Blue Note design is just cool, and the retro angle makes sense for a reissue.

The lyrics on ‘Milo Goes to College’ capture a very specific moment of adolescent angst, from parental frustrations to suburban boredom. Looking back after all these years, is there a song that hits differently now, maybe feels more raw or weirdly spot-on than it did back then? Is there a lyric you wrote that’s taken on a new meaning for you as you’ve gotten older?

‘Suburban Home’ was written by Tony [Lombardo], and he really did want a suburban home. He was already in his late 30s when he wrote it, so he was truly looking to “settle down.” It’s not tongue-in-cheek at all. The rest of the band would make fun of Tony for his more grown-up perspective, whereas now we all have suburban homes, so I guess he has the last laugh!

Let’s go way back to before ‘Milo Goes to College’ was even a thing. What would we have found in your teenage bedrooms? What records were you guys playing over and over, what zines were you swapping, and what local hangouts or clubs really felt like the place where the band started to take shape before anyone knew who you were? We’re talking pre-‘Fat’ EP days here.

I was listening to X, Buzzcocks, Black Flag, Germs, Undertones—anything power pop or LA punk-based was on the turntable. Plus weirder bands like Pere Ubu, Saccharine Trust, and of course the Minutemen. I didn’t know many fanzines at the time, but I bought Flipside occasionally. For shows, we’d go to Hollywood, places like the Whisky and Starwood. Bill went to the Masque and the Fleetwood; those closed down before I discovered them. The Cuckoo’s Nest in Orange County always had great shows too.

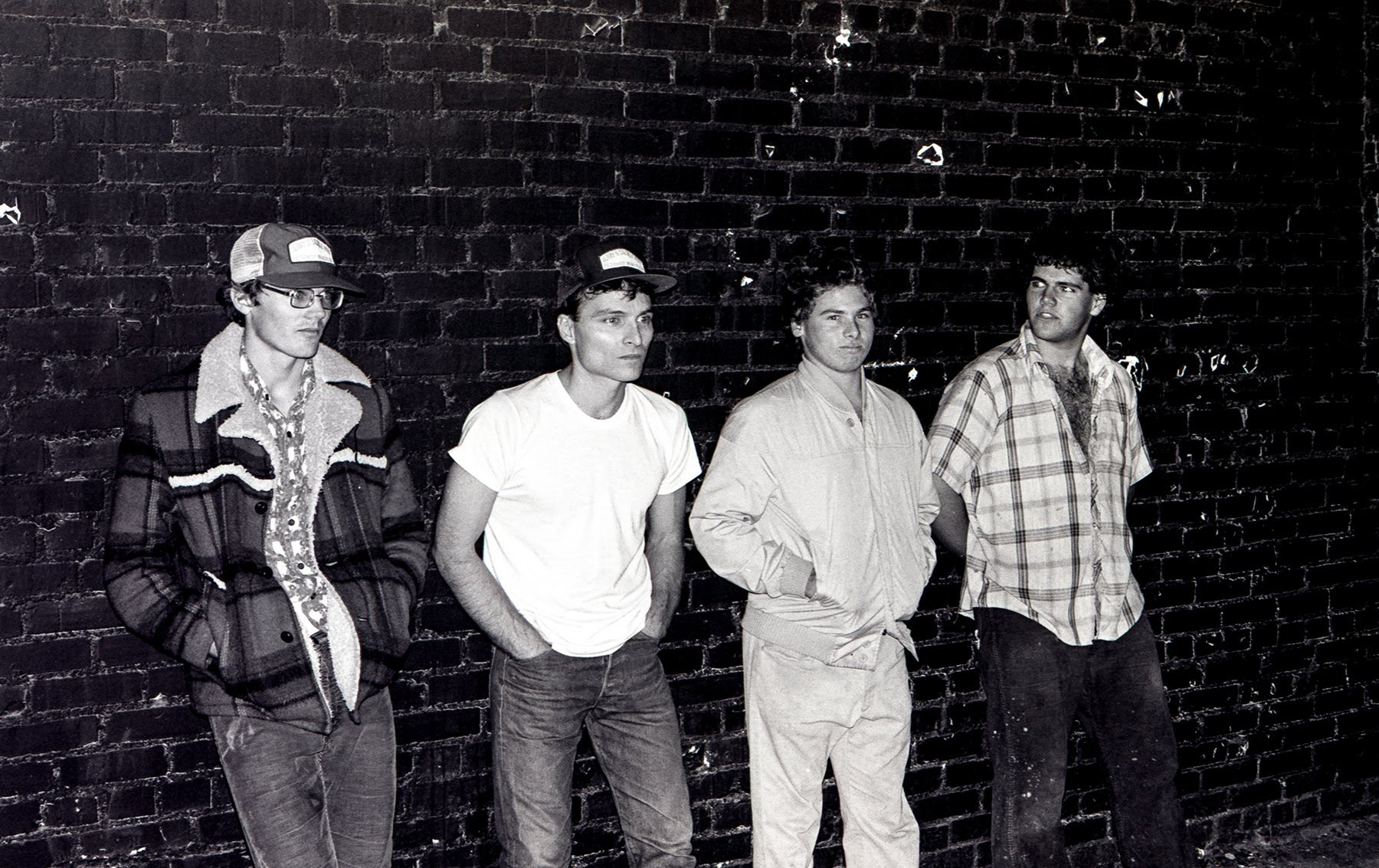

You’ve mentioned in the past that the song ‘Tonyage’ was written as an homage to Tony Lombardo’s basslines. That track, along with songs like ‘I’m Not a Loser,’ really shows off how sharp and original the playing was in the early lineup. How do you feel the unique musical personalities of Tony Lombardo and Frank Navetta shaped the foundational sound of the band? What sticks with you most about the vibe and connection you had as that original four-piece?

Tony brought in a quirky new-wave sense of humor, whereas Frank’s humor was darker, more bitter. As for sounds, Tony again leaned a little more new-wave, but Frank had this odd combination of 60s influences and an aggressive punk guitar style. What they really shared, what we all four shared, was a sense of being outcasts. Bill, Frank, and I were indeed outcasts at our school, not with the popular cliques, and Tony, due to his age, was a square peg in a round hole because everyone around him was so much younger. We bonded together over this sense of not belonging, and the lyrics obviously reflect that.

Can you remember any gigs or moments that hit so hard they changed the way you thought about music? Maybe it was a band you saw live or a conversation at a show. What was that big “aha” moment for you?

The Bad Brains at the Whisky in 1982 blew me away. H.R. hung back off stage while the band started the first song, then when it was time for him to sing, he came tearing out and stage dived, grabbing the microphone on the way into the audience. It was crazy, and the first time I witnessed the impact of doing something truly dangerous in a live performance. I never had the guts to do that myself, but I definitely immerse myself within the audience whenever possible.

The ‘Fat’ EP is a huge milestone for a lot of fans. It feels like a perfect bridge between your raw early sound and the cleaner style that came after. When you were writing and recording it, did you feel like you were onto something new or was it just another day in the studio? What stands out most to you from that time in the band’s history?

That record exists mainly because of coffee. Under the influence of caffeine, we just wanted to play as fast and tight as humanly possible. I didn’t consider the speed itself anything new because Bad Brains and Middle Class were already doing it. The subject matter, though, was definitely novel; people weren’t writing songs about fast food or fishing, so that stuck out. And the whole concept of re-enacting a drive-through order from Weinerschnitzel—well, what can I say? Bill’s a genius.

The early ’80s punk scene was full of different local flavors, and the LA scene had its own vibe, one you guys were a big part of. How did growing up and playing in the South Bay, with its more laid-back, beach-town feel, shape your music and outlook compared to bands from Hollywood or other parts of LA? Did being a bit removed from the scene give you more room to do your own thing?

I think the laid-back thing really benefited the South Bay scene because people were very accepting of bands that wanted to do something more off-beat. And there was less fashion presence in the South Bay compared with Hollywood, so we didn’t end up going in for the Mohawks and leather jackets. We just dressed like we were going to school. Bands like the Minutemen and Saccharine Trust thrived in the South Bay, even if they didn’t fit into the Hollywood mold. The South Bay scene was also pretty tight-knit, almost like a family. SST Records helped foster this support structure for the local bands.

“The community spirit is borne of being the underdogs…”

Your lyrics often deal with being an outsider or not fitting into a certain mold, and that’s a big part of why the album connects with so many people. That comes through loud and clear on songs like ‘I’m Not a Punk’ and ‘Suburban Home.’ When you wrote those tracks, were you feeling alienated by both the mainstream and the punk scene itself? Do you think punk has ever been about building a new mold to fit into or has it always been about smashing every mold there is?

I partially answered this above. We didn’t fit in with normal society, but we also weren’t copacetic with the punk scene. I was a nerd, so to me it felt like I wasn’t cool in either world. Nonetheless, part of what was appealing about punk for me is flipping the bird to everyone so that you can just be yourself. Maybe that fits with the “smashing every mold,” but also if you’re searching to express your unique self, you’re best served by building something new. So a little of column A, a little of column B.

With this big reissue campaign, you’re not just revisiting ‘Milo Goes to College’ but also an entire era with ‘I Don’t Want to Grow Up’ and ‘Enjoy!’ coming up. That must bring a lot of reflection. What is one piece of advice you would give your 1982 selves about the music you were making or life in general?

I used to have all these regrets about splitting up my time between music and science because each pursuit seemed to suffer as a result. But now I’m more philosophical about how it all went down. You can’t do all things all the time, so just do what you’re most passionate about at the moment. Then you hope that short-term satisfaction can eventually be paired with some sort of long-term fulfillment, whatever that works out to be. All I know is, I wouldn’t have done it any differently, knowing what I know now.

You’ve always balanced aggression with catchy hooks in a way that helped define a whole genre. When you recorded ‘Milo Goes to College’ was that something you were trying to do or just how things naturally came together with the four of you in the room? Were there any talks about pushing back against the tighter hardcore rules at the time?

We didn’t really discuss our musical direction. We just each brought our own approaches to the music. There was a shared love of punk, but we each had different influences outside of that. I was a big Beatles fan, so I figured that maybe I could sing some melodies instead of just yelling. But I also wanted to be Dez Cadena, so there’s the hybrid. That could be said of every member. Each of us had those same tendencies to be melodic but also kick ass. I guess that’s why it came naturally.

Jumping to the present, your influence is everywhere. A lot of bands are clearly pulling from that melodic hardcore sound you helped shape. What’s it like seeing traces of your style in today’s music? Do you think the current scene carries the same energy and fun you had back then, or does it feel like a different world now? I wasn’t around for the early days of hardcore, but I get the sense that what you had was something special. The community, the love, the chaos, and the DIY spirit all felt real and alive. These days, it feels like some of that is missing, especially the community part. Does it feel that way to you too?

I get the feeling that same sense of community exists, but maybe not in our exact genre. Maybe it’s in some burgeoning, under-the-radar type of music. I say this because the community spirit is borne of being the underdogs, the “Unheard Music” (to quote X). Underdogs stick together because in some cases, all they have is each other. That’s where community starts. And DIY goes hand in hand with that because there’s no other choice. My daughter is in a band down in Durham, NC, and I can tell you there is a sense of community there, if only because the scene is so small. Everyone is helping her band, Little Chair, get some exposure, and it gives me hope that independent DIY music can still thrive.

Alright, last one. Imagine you’re on the road, your van breaks down in my little town, and I invite you over. I’m a total music freak with shelves full of records. What do you think we’d end up spinning? What records would you reach for? Could be anything, no rules.

I would be pissed at the van breaking down and put on ‘Car Trouble’ by Adam and the Ants. And I would be kvetching about how this always seems to happen on tour—touring can be a real pain in the ass—and then put on ‘Life on the Road’ by ALL. We’d get talking about your little town and play ‘My Little Town’ by Simon and Garfunkel. Then, tired of lifting up the needle so many times, we’d put on ‘Close to the Edge’ by Yes and decide, what the hell, let’s play the whole ‘CTTE’ album. But while it’s playing, we’re arguing about the longest prog song, whether it’s Jethro Tull’s ‘Thick as a Brick’ or something by the band Green Carnation. Since you don’t have the Green Carnation one, we’d play ‘Thick as a Brick’.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Ed Colver

Descendents Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / Bandcamp / YouTube

Org Music Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / Bandcamp / YouTube

Good to see another legendary Punk band featured here.