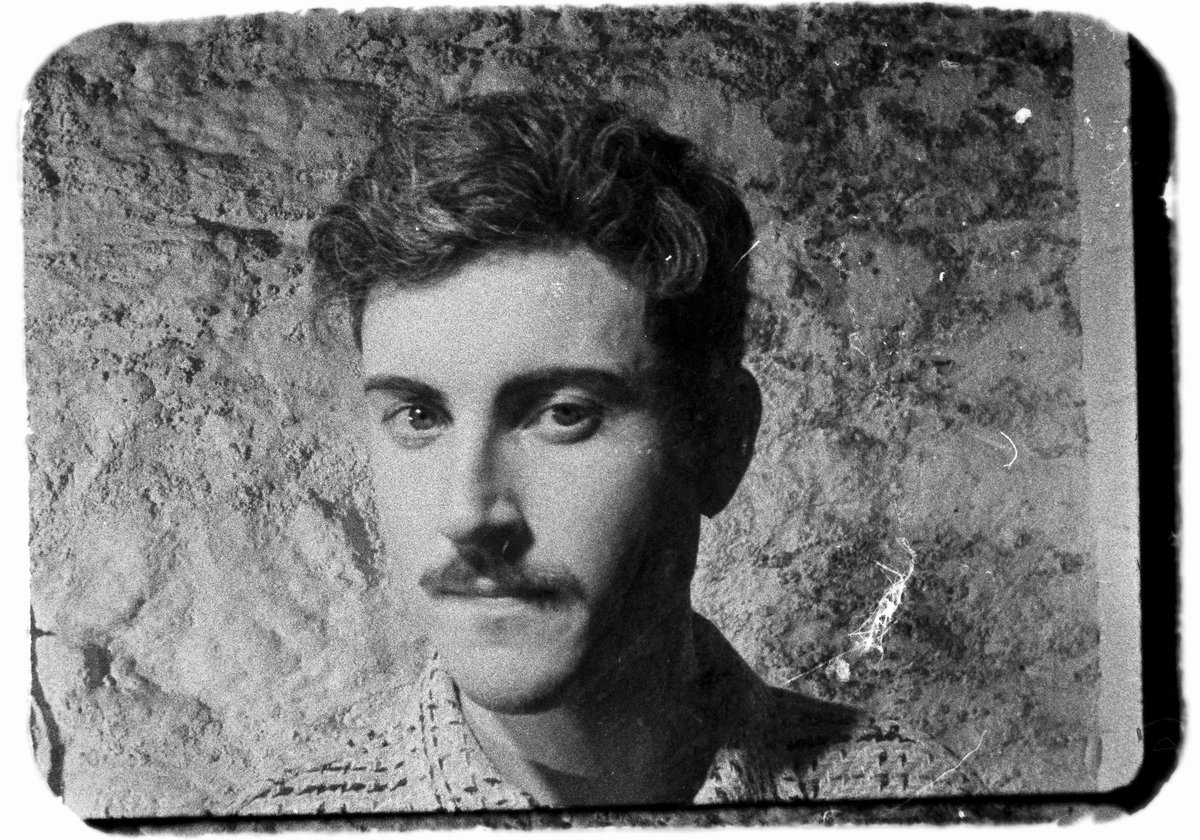

Inside ‘The Ruin’: Elliot Galvin on His New Album

Elliot Galvin’s ‘The Ruin’ is a haunted, deeply personal album that plays with memory like it’s something you can rewind, loop, and slowly piece back together.

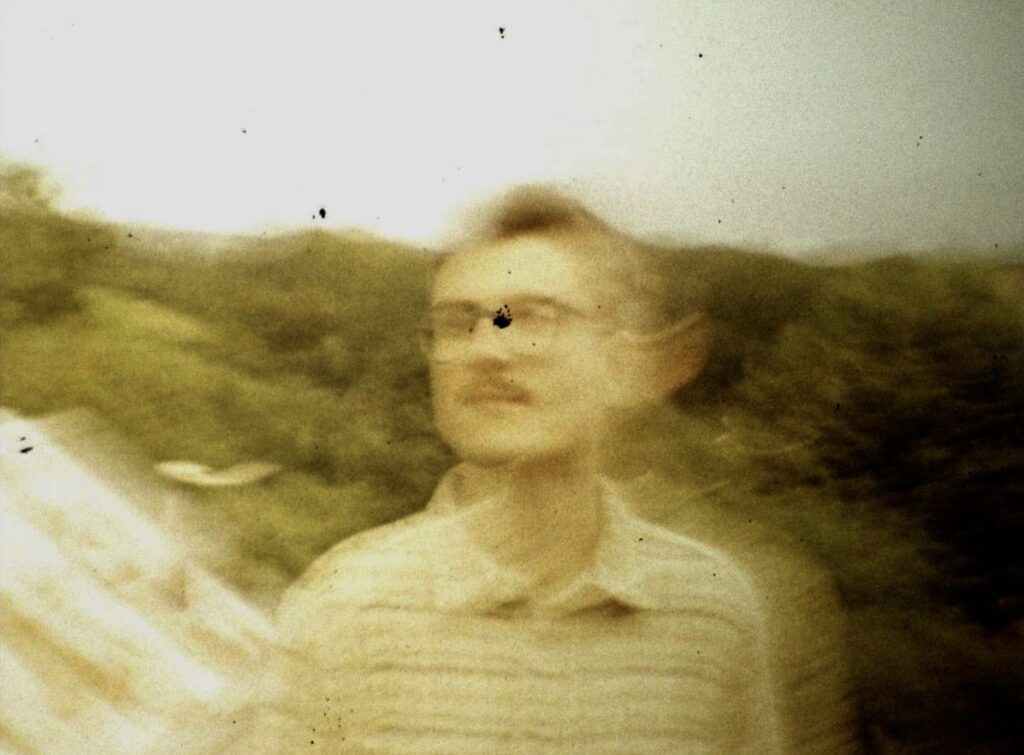

It starts with a reversed iPhone recording of Galvin playing his childhood piano—the same one he bought with money left to him by his grandfather—and ends with that same clip played forwards. What begins as a ghost of a melody ends as something clearer, warmer.

The album is built from old recordings Galvin made years ago, back when he was just experimenting alone. Those fragments, originally meant for no one else, became the foundation for a beautifully strange collection of pieces. Strings (played by the Ligeti Quartet), synths, voice, drums from Seb Rochford, bass from Ruth Goller, and a cameo from Shabaka Hutchings help bring the whole thing to life. But it still feels intimate, like you’re hearing Galvin talk to his past self through music.

The video for ‘A House, A City’ shows him calmly playing a piano as it burns in the middle of a field. It’s not just an arresting image—it says everything about this album. ‘The Ruin’ is a way of letting go. Not dramatic, not tragic, just necessary.

Galvin says it’s the most personal record he’s made, and it sounds like it. It doesn’t just sit with memory. It turns it over, sets it alight, and somehow makes something new from the ashes.

“I’ve always been fascinated by sound.”

Elliot, let’s start with the fire. You literally set a piano on fire for the video of ‘A House, A City.’ It’s an incredibly powerful image. Was it cathartic for you, or more of a ritualistic farewell to the past?

Elliot Galvin: Strangely enough, it’s always been something I wanted to do. The action of doing it for this music video was, I would say, more ritualistic. There’s something powerful and pure in the simplicity of setting a piano on fire. It also made total sense to me with the ideas behind the album—making something new from destroying something old.

Memory plays a huge role in this record. You built ‘The Ruin’ from old iPhone recordings and scraps of improvisations from your childhood piano. Was there a particular moment, going through those recordings, when you felt like, “This is the seed of the album”?

There was one improvisation I recorded on my iPhone in particular that, even when I recorded it a few years ago, I knew would be on an album. I let the seed of that idea grow in the back of my mind for a few years until it felt like the right time.

There’s a fascinating circularity to ‘The Ruin.’ The album starts and ends with the same reversed recording, mirroring the rise and fall of memory. Were you thinking in cinematic terms, structuring it almost like a narrative arc?

Totally. I was particularly interested in exploring form with this album, and building in those little signposts was a great way to play with that. Specifically, with starting and ending with the same sample, I was inspired by the book Finnegans Wake by James Joyce, which starts with the end of a sentence and finishes with the beginning of the same sentence.

You talk about England as a “living ruin.” That’s a potent and loaded statement. Was this album a response to a specific moment, or more of a long-simmering feeling about the state of things?

More a long-simmering feeling. It’s an old empire; there’s a lot of history that hasn’t been dealt with, which we live amongst as a kind of collective psychic ruin. Some people imagine glorious pasts with these ruins without facing the reality of their history.

Improvisation is at the core of what you do, but this record feels very composed, very intentional. Where do you draw the line between pure improvisation and composition?

I think it’s grey. For me, it’s a spectrum. In the same way, I don’t like to be too prescriptive with genre, I also don’t like to be too prescriptive with improvisation. Sometimes it’s good to abandon the written material for something improvised, and sometimes you don’t need to improvise at all—just playing a simple pre-written melody is the strongest statement.

You’ve worked with some of the most boundary-pushing musicians in jazz—Shabaka Hutchings, Emma-Jean Thackray, Binker Golding. What did you take from those collaborations that fed into ‘The Ruin’?

I have been lucky enough to work with some amazing musicians. The thing I take from everyone I work with is how they approach music differently. Each has a very clear vision, and there’s something inspiring about trying to find a way to present your own voice that still holds true to their aesthetic. It makes you reflect on what it is that you want to communicate, which is definitely something I’ve tried to put front and center on this record.

There’s a ghostly presence of your grandfather in this album—the piano, the recordings, the inheritance. Did you feel like you were in conversation with him while making it?

It’s something I realized afterwards, I would say. While I was writing the music, I was just trying to follow a feeling. But looking back now, with it all finished, I can see that coming through.

Sonny Johns, who’s worked with Tony Allen, Ali Farka Touré, and Damon Albarn, produced the record. What did he bring to the sessions that shaped the sound?

I’ve worked with Sonny on a number of albums. He’s a very responsive person and is great at facilitating your vision. He brings a calm energy to what can sometimes be a stressful environment.

The Ligeti String Quartet appears on The Ruin. Ligeti himself was a master of dissonance and decay. Was his music a direct influence, or is that just a happy coincidence?

I would say Ligeti is maybe my biggest influence in a number of ways. I discovered his music when I was about 14, and it’s no exaggeration to say that it changed the way I wanted to make music.

This is your first album with Gearbox Records. What drew you to them, and how does it feel to be part of a roster that includes artists like Binker & Moses and Abdullah Ibrahim?

I’ve always respected what Gearbox Records has put out. This album felt very different from what I had made before, and it felt like it needed a new home. I reached out to Darrel, and he seemed to get the music and be receptive to my ideas. That’s all I really want in a label, to be honest.

You’ve created experimental works for galleries and commissions for the London Sinfonietta. How do you approach writing an album like ‘The Ruin’ compared to a piece for an art space or an ensemble?

I increasingly try to approach everything the same. There is something I want to communicate, a sound world I want to create. It’s then just a question of the best way to make that work with the tools you have. With improvising musicians, like the ones on this record, I think it’s more about giving them the freedom to make something in the world you outline.

Your previous solo record was entirely improvised piano. ‘The Ruin’ is a mix of piano, synths, strings, and voice. What was driving that shift?

I’ve always been fascinated by sound. I love the sound of the piano, but it has its limitations. When I started making this record, I wanted to make something with as little sonic limitation as possible, and using these forces allowed me to explore those things.

Your music sits between jazz, contemporary classical, and something more experimental. Do genre labels ever feel restrictive, or do you enjoy the ambiguity?

I don’t really think about genre too much. I grew up outside of any particular musical tradition. I respect musicians who create something beautiful within one particular style, but it’s never been something I’ve been that attracted to making myself, or even that good at, to be honest.

Finally, this album is about ruins, but also about rebuilding. What did making The Ruin teach you about yourself?

Good question. Maybe it was more of a revealing experience than a teaching one. It showed me the music I really want to make. And maybe that’s not the music I thought I would make.

Klemen Breznikar

Elliot Galvin Website / Facebook / Instagram / YouTube

Gearbox Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube