Lotti Golden’s ‘Motor-Cycle’: The Downtown Epic That Captured the Sixties Underground

Lotti Golden’s 1969 debut, ‘Motor-Cycle,’ stands out as a unique record from the singer-songwriter era. The collaboration between Golden’s music and producer Bob Crewe’s ended in an almost conceptual symbiosis.

While she gained cult status for her groundbreaking 1969 debut on Atlantic Records, the album is a true psych-soul trip and might be called a semi-autobiographical chronicle of New York City’s counterculture scene. As mentioned, Bob Crewe helped to fuse urban poetry with elements of rock, R&B, and jazz, creating a sound that really lived in its own little world. Golden’s candid, confessional lyrics and dynamic vocals, often recorded live in a single take, truly managed to grasp the essence of street life and challenged the norms for female artists at the time.

‘Motor-Cycle’ challenged listeners, especially in an era when pop singles rarely went over three minutes. With its ambitious arrangements, extended instrumental sections, and a vivid cast of characters whose stories unfold across multiple songs, it might be the first rock concept album by a female artist. The album explores the joys and struggles of a group of outsiders, using their journey as a metaphor for rebirth.

This ambitious and original work immerses listeners in Lotti Golden’s experience within New York City’s late-sixties counterculture. The story moves from the East Village to the Lower East Side and beyond. Its characters include philosopher-lovers, gurus, grifters, and groupies. It is one of the truly remarkable albums to come out of that specific and highly influential time. Thanks to High Moon Records, we are able to play this one again and travel back to definitely more creative, if not that, then definitely more exciting times to be alive.

“Motor-Cycle was born in a cultural hurricane.”

Can you take us back to your Brooklyn roots? What specific moments or experiences from growing up in that vibrant neighborhood sparked your passion for music and art, and did it feel inevitable that you would become part of this creative revolution?

Lotti Golden: It’s interesting that you are asking me about growing up in Brooklyn and how it would inform my musical sensibilities because I have recently been working on an autobiographical song that addresses those years. The lyrics capture the feeling of growing up in a developing community far from the bright lights of Manhattan. These are some of the lyrics:

Play it Like a Song

Where I grew up was a small town

In the middle of New York

You cross a bridge to get there

then a 7-mile walk

to my house in summer

a jungle in the heat

Fireflies would light the way

down to old Mill Creek

It was 3 feet deep

Yeah 3 feet deep

My sister’s name was Glory

No I’m not kidding you

yes her name was holy

and her story was that too

She was born a problem

but her eyes were beautiful

Bluer than the ocean

and her heart was good and true

They said she was too smart

for her own good

for her own good yeah

and it played like a song

on the radio

my transistor radio

My daddy was a bar man

he was a sailor too

captain of his own ship

He fought in World War II

My mother was a movie star

people came from miles around

To watch her sway like a willow

Crossing Avenue L

in her flaming red bouffant

She worked in daddy’s restaurant

No waste no want

And when the moon was fat and still we wrote our bikes to the badlands for a race down suicide hill

Play it like a song on the radio

my transistor radio

© 2025 Lotti Golden

These lyrics evoke impressions of my Brooklyn roots. The neighborhood I grew up in in Brooklyn was new. It was a developing neighborhood, built on swamp land, way out in the boondocks. So growing up, the feeling was like living in a small town, rural America, isolated from the big city. I was the classic smalltown girl with big city dreams.

My parents loved the arts. My dad was a jazz buff: Lester Young, Coltrane, Miles. My mom was an amateur singer; she listened to Dinah Washington and Billie Holliday. During my early teens my mom was involved with a charity organization that performed an annual show to fundraise. I was about 11 or 12 when my mom played the part of Louise in their production of Gypsy. She was amazing singing and acting in the show and so incredibly gorgeous she mesmerized the audience. I had a small part where I played guitar and sang. (The show’s director was Carol King’s mom.)

This was around the same time that my parents gifted me a guitar. Funny thing was, traditional musical theater lab show tunes were not my jam (although Gypsy is an exception with a great score). I just wanted to write songs: rock songs, country, pop, blues, R&B, and Motown.

Some of my earliest memories growing up in Brooklyn were my attachment to my transistor radio. I was maybe nine years old when my parents gifted me that radio and my whole world opened up. The transistor radio was like the iPhone of its time. Portable and in my pocket, it went everywhere with me. The AM stations played every genre, including the pop songs of the day by girl groups from the Supremes to the Ronettes and teen throbs like Dion and the Belmonts. I remember my sister so excited, bursting into my room, “Did you hear it?”

“Hear what?”

“The song by the Shangri-Las, ‘Walking in the Sand.'” It was so exciting hearing the girl group sound direct from Queens and homegrown.

My parents were aficionados not only of music but of the arts in general: theater, foreign film, art. They loved all forms, particularly the avant-garde and experimental. When I would wake up on Sunday mornings, I never knew what evidence I would find of my parents’ Saturday night adventures in Manhattan. I was maybe nine or ten when a playbill on the kitchen table caught my attention. It was titled The Jewel Box Review. Wikipedia describes this theater group as the first traveling drag show in America. I learned early on that “the city,” or Manhattan, was the place where art, music, and magic happened.

My fate was likely sealed when my parents gifted me my first guitar at the age of 11. It was the perfect vehicle to fuse my love of writing poetry with music. It is worth mentioning that my parents supported my dreams with music lessons, vocal and drama lessons. I consider myself lucky. They did not caution me to be practical. They gave me permission to go for it.

In those hazy, heady days of the 60s, coffeehouses were melting pots of emerging sounds. Which local artists or impromptu performances left an indelible mark on you, and do you have any unforgettable stories from those spontaneous nights?

Actually, the Greenwich Village coffeehouse scene was in its heyday before I came of age. The classic or peak, I would say, was late 1950s to about 1965, based on Bob Dylan’s arrival in New York City in January 1961, during the coldest winter in New York in a generation. I was only 11 years old that year, busting out homework until midnight but not nightclubbing, but I was blasting the radio, consuming music like Roy Orbison’s ‘Crying,’ ‘Crazy’ by Patsy Cline, and ‘Hit the Road Jack’ by Ray Charles. Some nights, I could not stop listening, and I kept that transistor radio under my pillow as it played the Isley Brothers, Sam Cooke, Mary Wells, Dee Dee Sharp, Hank Williams, Brenda Lee, the Marvelettes, and more. I did not know it then, but there were some great artists influencing my musical style.

Although I was too young to venture out at night, my dad knew how crazy I was about music and particularly about Bob Dylan. He was a jazz boss, but he had no problem embracing new trends and new artists. He was just as crazy about Bob Dylan as I was, so he got tickets to the Forest Hills Stadium for the iconic concert where Joan Baez introduced Bob Dylan to the folk music world. To this day, I do not know how my dad knew that Dylan would be performing that night because he was a surprise, unannounced guest.

As the 60s progressed, I was old enough to sneak into some clubs and coffeehouses. Your heart would beat with anticipation as you made it past the bouncer, gaining entry to the club. One of my favorites around 1966 to 1969 was the Steve Paul scene. It was the cool, trendy spot to be seen in the mid 1960s, a basement club on 46th Street, literally underground. By 1967, the Velvet Underground had played the club, so the Warhol crowd started hanging out there. It was a small club, and the patrons always packed the dance floor. I got to know Steve Paul, the manager of the club, who was only in his early 20s. After Motor-Cycle was released, unfortunately I had no support to tour with a band, which I desperately wanted. Steve was kind enough to allow me to play early evenings when the club first opened, just me and my guitar, no publicity, but very rewarding.

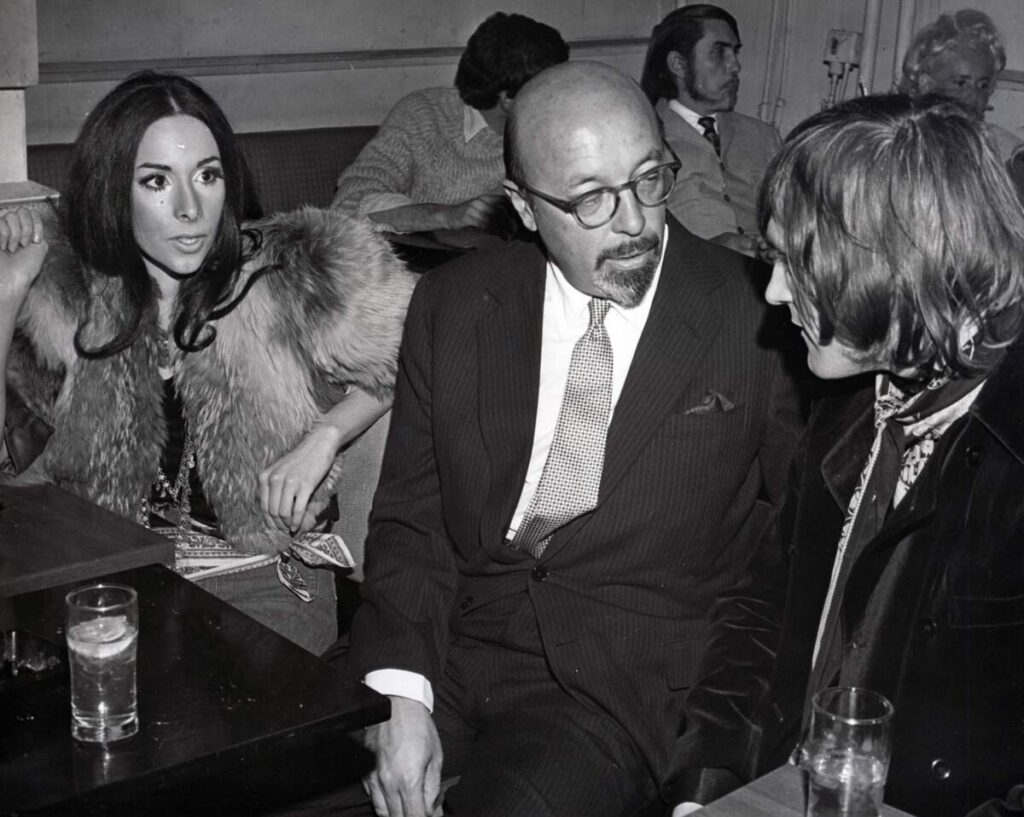

When I was 18 and signed with Atlantic, the co-owner of the label, Ahmet Ertegun, had a passion for nightclubbing with the purpose of discovering new talent. Ahmet and Jann Wenner of Rolling Stone and I would make the club rounds from the sleaziest to the most upscale, looking for the next big thing. I do not recall us discovering any great talent, but quite often great talent would join our quest, which is how I met Brian Auger, who went clubbing with us one summer night. We bonded over our love of music and managed to initiate some deep discussions in spite of the loud music via passing notes in real time.

I guess I always had a thing for guitar players. I met Johnny Winter through Steve Paul. There is a photo in Look magazine that captures me jamming with the McCoys, a band I met through Steve Paul.

In August 1969, the summer ‘Motor-Cycle’ was released, I was staying at the Chelsea Hotel on 23rd Street in Manhattan. The Chelsea was the ultimate 20th-century rock hang. Everyone stayed there. By chance I ran into Michael Bloomfield and Barry Goldberg. That was when they had formed their band, Electric Flag. We got to talking music and all things cool. Sometime during our discussion, Michael scored some hashish for fun. It was delivered to our room and we casually smoked it, resuming our conversation. We were in for a surprise; no one expected that batch to be so potent, and we became so smashed we were practically incapacitated, causing Michael and Barry to miss their flight to London for a festival they were booked to play and causing me to miss my ride to the Woodstock Festival. That crazy chance encounter was the start of a friendship that lasted for many years.

“Music would be forever changed by Monterey Pop Festival.”

You were remarkably young when you immersed yourself in New York’s countercultural energy. The beat poets, the jazzers, the folk troubadours. How did the eclectic spirit of the East Village and Lower East Side shape your artistic identity during those formative years?

I was 14 or 15 when I began taking dance and drama classes at New York City Henry Street Settlement on NYC’s Lower East Side. The storied institution was my window into the New York City counterculture in the 60s. In drama class and playwrighting classes I was befriended by neighborhood locals who turned me on to the happenings in the East Village and Lower East Side. I was invited to galleries, jam sessions, and parties.

‘Motor-Cycle’ was born in a cultural hurricane. No other decade in modern American history, certainly in the 20th Century, has impacted American culture like the 60s. The decade moved quickly through fashion trends beginning with the iconic pillbox hat and bouffant hairstyle worn by Jackie Kennedy, through the Mod trend imported from the UK and made famous by Vidal Sassoon’s geometric haircuts to hippie fashion and flower power courtesy of the San Francisco music scene. Yes, I was very young to be immersed in the counterculture, but the 60s was revolutionary in that it was a youth movement. No aspect of American life was untouched by the 60s, from the civil rights, anti-war, feminist, and gay movements to science and technology culminating in landing a man on the moon. The Sixties impacted every aspect of society, socially, politically, and artistically. It was an incredible time in history to come of age. The East Village and LES was electric. I met artists, poets, guru-philosophers, and ne’er-do-wells.

I was 16 when I met a boy, Michael, who was enrolled in my drama class. That fateful encounter was the catalyst for ‘Motor-Cycle,’ which I began chronicling in poetry around 1966 to 1967. It was not long before I shaped the poetry I was writing into lyrics and the album started taking shape. The world Michael introduced me to included the seedy side of the counterculture, the hangers-on, ersatz artists, druggies, wannabe philosophers, musicians, and artists. What I encountered was often shocking and I felt compelled to document events. Creating ‘Motor-Cycle’ happened over a two to three year period.

The media branded 1967 the Summer of Love. Music would be forever changed by Monterey Pop Festival. But I did not go out to California. I opted instead to apprentice at summer stock theater in North Carolina. That is where I met Silky, one of the main characters in the motorcycle story. Eventually Silky relocated to New York City and participated in the underground scene happening in New York from late 1967 to 1969.

When I auditioned my idea for ‘Motor-Cycle’ for Bob Crewe, playing some of the songs live (accompanied by my guitar) in his office, he was floored, exclaiming, “Who are your friends?” Those words inspired the only song on the album I co-wrote and it was with Bob, titled ‘Who Are Your Friends.’

The electric beat of the streets, the music in the air, the underground clubs, art happenings and installations, Andy Warhol’s Factory, nights at Max’s Kansas City and the Fillmore East all contributed to the backdrop of the Motor-Cycle story. But what makes the album come alive, I think, are the characters, the players that populate the saga. I wish I could say I dreamed them up, Michael, Silky, Annabelle, and the rest. But this was a case of life imitating art. The characters and stories I tell in ‘Motor-Cycle’ are not fiction. These people existed and these events happened, of course told from my perspective in shaping the narrative. Motor-Cycle could be thought of as a kind of musical analog to Joan Didion’s prose, chronicling the California Sixties counterculture, telling non-fiction stories with the dramatic flair of fiction.

You are asking how my immersion in the NYC counterculture shaped my artistic identity in those formative years. Yes, as I described here, ‘Motor-Cycle’ is very much a product of the counterculture. However, regarding my artistic identity, I believe it was formed much earlier. By the time I was hanging out in the East Village I was in my late teens. The way I see it is that my artistic identity was shaped before that, listening to my transistor radio, hearing the great pop artists of the day, reading tons of books, literature that was popular with young people like Catcher in the Rye, delving into Hermann Hesse, George Orwell, Huxley, Ken Kesey, Heinlein, Sylvia Plath, William Burroughs, Iceberg Slim, Ferlinghetti, the Beat Poets, Kerouac and Ginsberg.

Picking up guitar and writing songs as a preteen, studying vocalists like Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles, learning their vocal runs and licks which I practiced, recorded, and perfected using a home reel-to-reel tape recorder, reading and writing poetry, studying drama and playwrights, all were disciplines that formed the basis of my artistic identity so that I had the tools to tackle a project as sweeping and daunting as ‘Motor-Cycle.’ The undertaking required vocal ability, an understanding of poetry, prose, and lyrics combined with songwriting skills and musicianship. I could not have accomplished writing and recording ‘Motor-Cycle’ without the discipline required to build that artistic foundation.

Before Atlantic Records took notice, did you spend countless nights on small stages or in underground clubs? What was that pre-fame scene like, and how did those early live shows forge the sound and confidence that would later define your career?

Before Atlantic took notice, I was not playing in clubs downtown. I was still in high school and too young. It was challenging even getting past the bouncer without fake ID. I did, though. I have stage experience, playing Top 40 type gigs with local bands. By the time I encountered Bob Crewe, I was a high school senior, signed as a staff writer to his publishing company. In addition to writing pop songs with other writers at Saturday Music, I was working on the material for ‘Motor-Cycle.’ By chance, I took the same elevator as Bob Crewe one afternoon, leaving a demo session. I had not seen him in person before but recognized him immediately. He was strikingly handsome with gorgeous blond locks that were privileged to be growing from his scalp. It was my opportunity to pitch him, and I went for it, telling him I was one of his staff writers, working on material for an artist album. He invited me to make an appointment and play my material for him. ‘Motor-Cycle’ was born via that chance encounter.

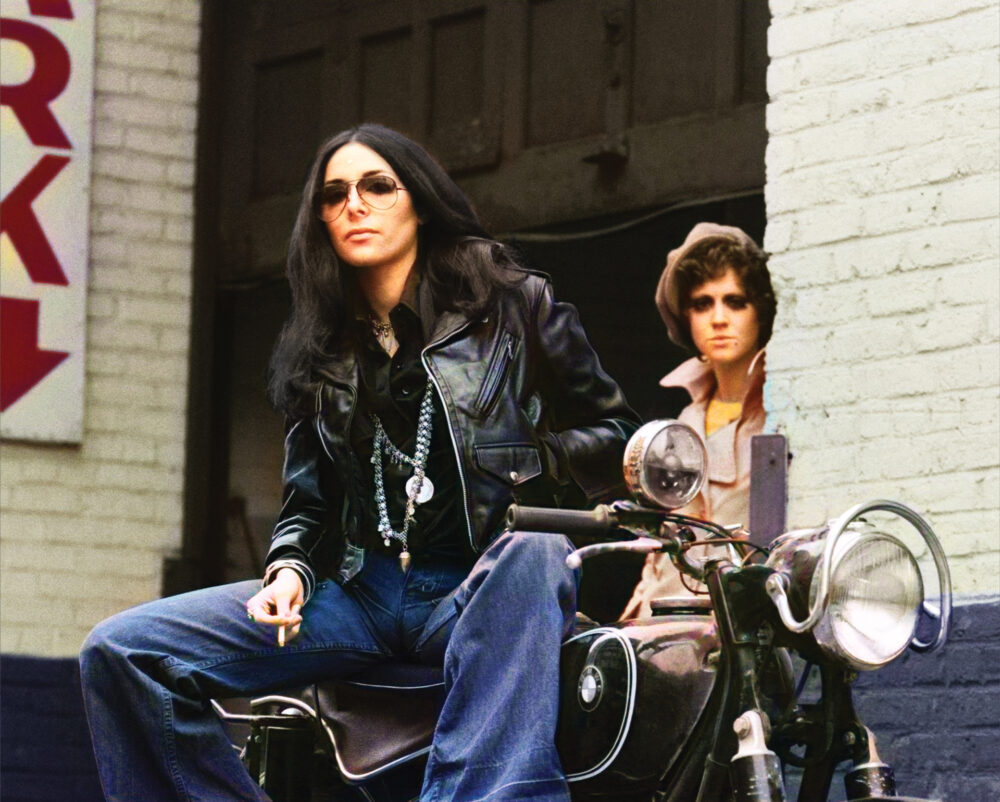

The day of the appointment I walked into Bob’s office wearing oversized aviator sunglasses, my black leather motorcycle jacket, sailor-style jeans from the army-navy store, and lots of vintage silver jewelry including rows of bangle bracelets that made their own music when I spoke, excitedly gesticulating with my hands.

By the time I played my music for Bob, I had done my homework, spending hours writing the music and lyrics. So when I presented the songs, singing and playing the guitar, I was fairly polished and ready to make a record. Preparation and practice, perfecting my craft, were what forged my confidence and desire to pursue my career. Plus, I had something to say, something I felt almost compelled to share with the world about my generation in a unique moment in history.

Before writing ‘Motor-Cycle,’ I wrote songs, pop songs, country songs, rock songs, all kinds of songs. Radio at that time was not divided by genre as it is today. So I was exposed to everything, including folk, spirituals, gospel, and jazz.

As a staff writer at Bob Crewe’s publishing company, Saturday Music, I wrote and produced song demos with my collaborators. In fact, High Moon Records discovered the song demo of ‘Dance to the Rhythm of Love’ in a warehouse, slated for demolition. This was the cover I landed, recorded by Patti LaBelle and the Bluebelles in 1969. It was amazing to hear it after all of these years. It sounded better than I could have imagined, so good in fact that High Moon Records reissued the song. I can be very discerning when it comes to hearing my vocals, but my performance provided insight into my state of mind during the time of ‘Motor-Cycle.’ On ‘Dance to the Rhythm of Love,’ I sound similar to ‘Motor-Cycle,’ but more relaxed, like I am having fun. It is a stark contrast with the urgency and intensity of the vocals on Motor-Cycle, with good reason. Bob Crewe produced the album, projecting his vision, and I co-produced the demo with my vision. As producers, we both got the results we were looking for. I will also add that the track is a seamless blend of R&B, rock, and soul.

“The poetic urban landscape of ‘Motor-Cycle’ reflects my love of poetry and poets I admire like Ferlinghetti and Sexton, Sylvia Plath, and more.”

(Your debut album) ‘Motor-Cycle’ unfolds like a cinematic journey through the gritty yet poetic urban landscape of New York. How did you conceive the idea of an extended song-suite with non-traditional structures that defied the conventional verse/chorus format of the time?

My staff writing gig with Saturday Music was my day job, so to speak. Conceiving ‘Motor-Cycle,’ with its nontraditional structure, was a way to free myself from writing conventional songs. Music at that time was undergoing a major transformation, beginning with the Rolling Stones and the Beatles in the early 60s, progressing through Jimi Hendrix and onto the Doors who played with song structure and lyrics, breaking with the conventional two and a half to three minute radio song. Music was changing, morphing from the traditional rock and roll of Chuck Berry to a more sophisticated rock, embracing literary influences, creative lyrics, and new subjects to sing about. By the mid 60s, the Doors were incorporating poetry and jazz, and The Velvet Underground fused pop sounds with gritty lyrics and images. I had no lack of creative influences informing ‘Motor-Cycle.’ The poetic urban landscape of ‘Motor-Cycle’ reflects my love of poetry and poets I admire like Ferlinghetti and Sexton, Sylvia Plath, and more. I read voraciously the novels that circulated among my generation—books by Hesse, William Golding, Huxley, Kesey, George Orwell, William Burroughs, and the sci-fi writers from Asimov to Heinlein and Philip K. Dick. I read the philosophers Camus, Nietzsche, and Kafka, and of course the Beat Poets.

I have often said in interviews how Bob’s vision of ‘Motor-Cycle’ and mine differed when it came to recording the vocals. The advent of 24-track recording allowed the luxury of overdubbing vocals to correct any mistakes or imperfections. By the time I recorded ‘Motor-Cycle,’ this was commonplace. But Bob objected to any overdubs. He objected to fixing any imperfections. He was convinced that the authenticity of Motor-Cycle would be destroyed using these techniques and the rawness of singing the songs in one cohesive take was what the spirit of the music demanded. This was Bob Crewe’s way of capturing what is almost a meme today: authenticity. I sang live with a band, rhythm section and horns completing the recording in two 12-hour sessions.

Collaborating with a visionary like Bob Crewe, whose “Wall of Sound” approach is legendary, must have been electrifying. Can you describe how that intense studio dynamic and the decision to record your vocals live in one take influenced the raw, immediate energy of ‘Motor-Cycle’?

Singing live for all those hours was a daunting task. Aside from requiring incredible vocal proficiency, the physical demands were the equivalent of being an Olympic athlete or performing a one-woman Broadway show without an intermission. I am not kidding; to sing for eight to twelve hours required physical fitness and stamina. A really great thing that came out of singing live with the band was the many improvised ideas that were created on the spot by myself and the musicians. Those who have a trained ear can even catch when I was going for a certain chord change vocally and the band was somewhere else. But we all caught it and made it work. There are so many surprises listening to the recording. There is always something new to discover.

Initially, I was upset with Bob about not letting me overdub or fix sections where I thought the vocals could have been better executed. But with time, I really do commend Bob Crewe for his vision. It was kind of genius to see that a slick or more perfect vocal performance would cancel out the urgency and the drama unfolding in the narrative. Bob’s wisdom as a producer has kept the album fresh over the years, as if the music and vocals are happening right now for the first time, unfolding as you listen.

The making of the album ‘Motor-Cycle’ was a drama in itself, from the marathon live recording of the record to being signed by Atlantic. Bob Crewe’s idea was to cut a few demos of the songs and shop them to get a major label deal. Bob took the tapes to Atlantic Records and played the demos in Jerry Wexler’s office. Jerry did not even wait for the last song to end when he said he wanted me on Atlantic, in effect signing me on the spot based on one listening. Gearing up for the sessions, Jerry was like a mentor. My voice reminded him of his protégé Aretha Franklin. He believed that I would be a star.

The release of ‘Motor-Cycle’ was fraught with challenges, missteps by Atlantic Records and a shifting industry. How did those early setbacks shape your approach to your art and inform your evolution as a songwriter, producer, and creative force?

If you had to come up with a script about a record label failing an artist with so much potential, my behind-the-scenes story of ‘Motor-Cycle’ on Atlantic Records is the one you would write. Before the album was released, even before we had finished recording, the buzz around the album generated copious press. You could not buy that publicity with the most dedicated PR campaign. It happened organically: a feature story in Look magazine, a cover story in Newsweek touting Joni Mitchell, Laura Nyro, Melanie and me as a new female singer-songwriter phenomenon, and multiple photo shoots in Vogue magazine for starters. At the label, Jerry Wexler and Ahmet Ertegun, the label’s founding fathers, were personally involved. Ahmet and I were kindred spirits, lovers of R&B and jazz. Jerry was a mentor sharing his ideas about vocalists and soul and R&B music. Bob was my producer and bestie. There was no doubt I was going to be Atlantic’s next big star. What could go wrong? Everything.

The album was released in May of 1969. There was a glimmer of FM radio play, then silence. Nothing was happening. I felt as if I were Odysseus, so close to my destination but getting blown back to where I started and enduring the despair of having to start over. The reason why Motor-Cycle did not happen remained a mystery to me. But with time and experience, knowing how the music industry works, I began to understand the obvious missteps. Unfortunately, I was not the first artist or band to experience this—the record company fumbling a release. We will never know how many great artists were lost to ineptitude, blunder, or just plain bad luck.

When I signed with Atlantic in 1968, the label was undergoing major restructuring. Although I was personally signed by Jerry Wexler and Ahmet Ertegun, both a tremendous support system introducing me to the label and during the recording sessions, big changes at Atlantic were afoot. Just a year earlier, in 1967, Atlantic was sold to Warner Brothers, and by 1969, when ‘Motor-Cycle’ was released, changes were being implemented at the label.

Jerry Wexler became disenchanted with the new corporate set up and initiated his relocation to Miami while dedicating his efforts to recording Dusty Springfield’s first Atlantic LP, Dusty in Memphis, which was really Dusty in New York; Jerry completed the project at Atlantic Studios. So Jerry had a lot on his plate, while Ahmet Ertegun, my other champion, began spending time in London signing British rock bands on a tip from Julie Driscoll (some say it was Dusty), but regardless the recommendation panned out big time with Led Zeppelin releasing their debut Atlantic LP in 1969. When I needed them most, they were nowhere to be found.

Always busy, Crewe moved on to his next project. This should not have been a surprise because it took a year from the time I played Bob songs from ‘Motor-Cycle’ in his office to clear his schedule to work on the record. Later in my career as a producer and writer, I would come to know this is how a producer operates, from project to project, but then it felt like betrayal. I was so young, with little understanding of the music industry and no one supporting me. And that is the key to it. All an artist needs is support. All of the great artists at the time had great managers. Albert Goldman managed Bob Dylan and Janis Joplin. Joni Mitchell was managed by Elliot Roberts. These managers were dedicated to their artists.

At a dinner party Bob Crewe arranged to introduce me to the New York music intelligentsia, the guests included Laura Nyro and her manager David Geffen, who followed Laura’s every step, shadowing her every move. That is the kind of commitment and support an artist needs.

1969 was a watershed year for Atlantic releases: Dusty Springfield, Led Zeppelin, Crosby Stills Nash and Young, Aretha Franklin, and the list goes on. The promotion department can only handle a certain amount of product and so this is where the adage, “the squeaky wheel gets the grease” applies. The manager with the loudest, bossiest voice will get his artist’s record moving. I did not have a manager. I had no one pushing for me. I was truly alone and it was devastating.

Another misstep is so obvious it is difficult to understand: there was no single released before the album. It is traditional to release a single before an album. But there was no single forty-five announcing ‘Motor-Cycle.’ Yes, the songs were long, but as recording engineers would say back then, “that is what razor blades are for,” meaning the song could have been edited for radio down to three minutes. So there was no single release, no manager, and everyone involved in the project had moved on. There was no one promoting the record at Atlantic to radio or distributors. So how in the world could this record happen? It could not. I blamed everyone. I blamed myself. It was soul crushing.

Something similar happened to Chappell Roan, an artist who also writes autobiographical songs in the style of confessional poetry. She has a similar story and was also signed to Atlantic. The label was all in, recording her debut LP and priming her as the next mega star. Then she was dropped unceremoniously. She had to leave California and move back to Missouri, deflated and depressed, as she recounts in her hit, ‘California.’ This artist somehow found the strength to pick herself up and get back in the game. Today Roan is the superstar she deserves to be, a once in a generation talent. Yet, when she is accepting an award or being interviewed you can still hear the hurt and bitterness in her voice when she talks about her experience with the record label. It is life shattering.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Photo by Baron Wolman, Lotti Golden on the streets of the West Side of NYC 1969. Silky (Silkman Gage) in the background.

High Moon Records Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / YouTube / Bandcamp

How necessary would a single have been? Remember that for all her acclaim, Laura Nyro didn’t have hits–maybe the problem here is that unlike Nyro’s albums, “Motor-Cycle” didn’t offer itself to cover versions. If anything, in that era of Hair and Tommy, it could have offered itself to a musical adaptation (and still could, for that matter, if anyone has the gumption to try)