Resonant Dissent: Excavating Slovenia’s Rock in Opposition

RIO: Rock v opoziciji is the first monograph to comprehensively document the Slovenian chapter of the Rock in Opposition (RIO) movement—an audacious, cross-disciplinary network that emerged in the interstices of Yugoslavia’s late-socialist cultural terrain.

This vital yet historically overlooked current unfolded on the peripheries of institutional recognition, where sonic experimentation met political disobedience and aesthetic refusal.

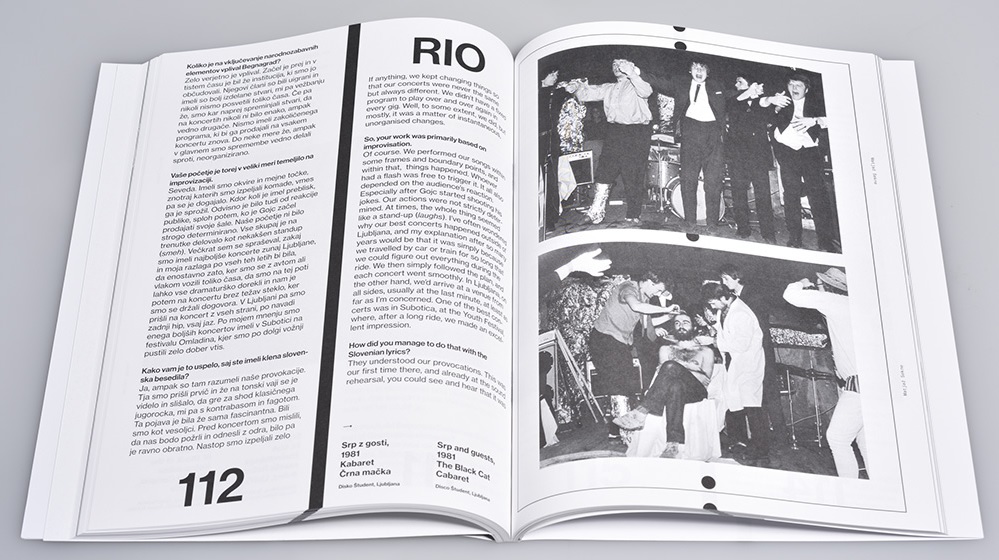

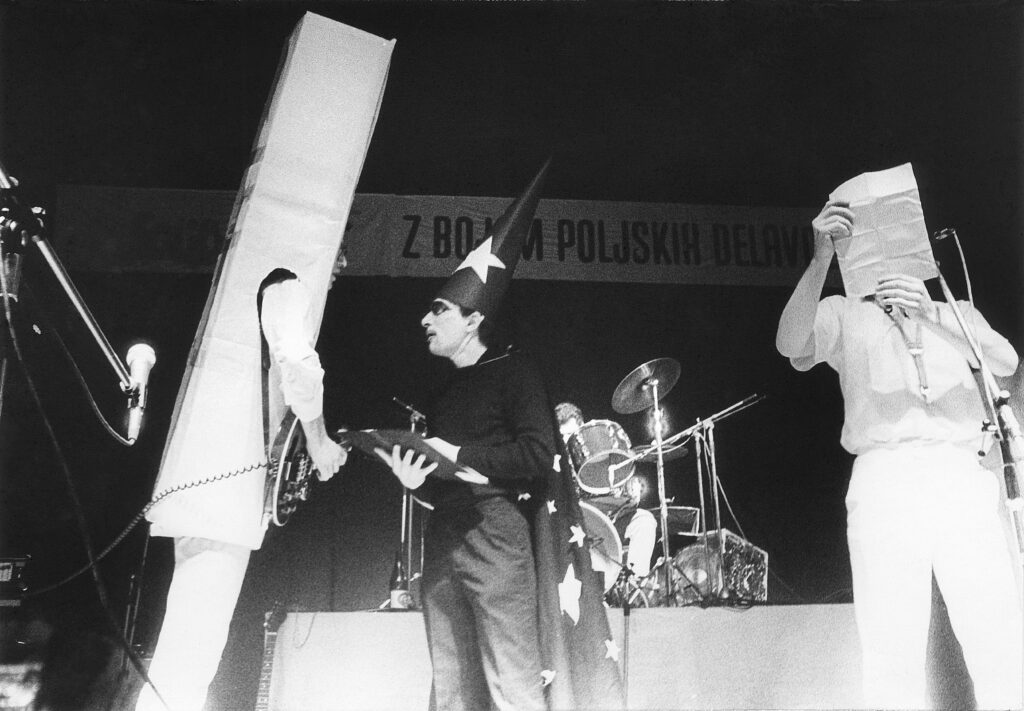

Co-edited by artist and curator Tadej Pogačar and music writer Igor Bašin (Bigor), the volume frames the radical visions of groups such as Begnagrad, Srp, and D’Pravda within a broader discourse of nonconformity, underground production, and post-1968 avant-garde strategy. These bands dismantled genre conventions, integrating improvisation, musique concrète, visual art, satire, and theatricality into dense, transmedial performance practices. Operating in a cultural climate often hostile to deviation, they forged new idioms of expression through scarcity, inventiveness, and sheer conviction.

Among the most pivotal figures of this scene is Aleks Lenard, whose radio program Untergrunt Molekula (Underground Molecule), broadcast via Radio Študent from 1974 onward, became a rare portal into the global underground. Lenard’s curatorial vision—also reflected in his wide-ranging writings for journals such as Mladina, Tribuna, and Džuboks—positioned RIO not merely as a genre, but as a methodology of belonging, improvisation, and resistance. His work, like that of visual artist Zorko Škvor and other key collaborators, established a fragile yet forceful infrastructure for oppositional culture in Slovenia.

Through interviews, archival reproductions, and reflective essays presented bilingually in Slovenian and English, RIO: Rock v opoziciji assumes the dual role of historiography and curatorial excavation. It draws from a fragmented oral and visual archive—handwritten notes, flyers, posters, personal testimonies—to construct a counter-canon that has long deserved its place in European experimental music history.

Part of the ongoing SEVENTIES series from P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Institute, the book does more than remember; it reactivates. By articulating the lived realities of artists working against the currents of commercialism and political orthodoxy, it insists on the urgency of listening anew. In doing so, it reframes the RIO movement in Slovenia not as a regional footnote to a Western avant-garde narrative, but as a fully autonomous field of sonic and ideological production—one where music became both a site of refuge and a weapon of resistance.

What emerges is less a document of the past than a challenge to the present. RIO: Rock v opoziciji reclaims a forgotten chapter in the cultural history of the Balkans and European undergrounds alike, and asks: what else have we ignored?

“The local critics failed to notice the emergence of counterculture”

What was your primary motivation for creating the first in-depth study on the Rock in Opposition phenomenon in Slovenia, and why did you feel now was the right time to explore this topic in such a comprehensive way?

Tadej Pogačar: This is the first study of Rock in Opposition, so in that sense, it has always been the right time. Now, some forty years later, as the artists grow older and memories fade, it is truly high time.

Since the book is part of the SEVENTIES series, which focuses on often-overlooked countercultural heritage from the 1970s, how does RIO: Rock in Opposition fit into this broader series?

With the 2022 exhibition Prijatelji bodo prijatelji (Friends Will Be Friends) at the P74 Gallery in Ljubljana, we began a new program series dedicated to the overlooked cultural production from the 1970s. This was an exceptionally fruitful decade in Slovenia in terms of experimental art, multimedia, the fusion of sound and theatre, performativity, social experimentation, and alternative culture. The latter is, of course, not an original phenomenon of the 1980s but of the 1960s and 1970s. The local critics failed to notice the emergence of counterculture, and so it was simply ignored. Rock in Opposition is a significant segment of counterculture creativity and has organically merged with other artistic productions.

The book includes a series of interviews with key figures from Slovenia’s RIO scene. How did you choose who to interview, and what did you hope to achieve by including their voices in the book?

When writing about historical artistic phenomena, I often encountered the questions of what to point out, what to choose, and how to make a selection. This process is, of course, subjective. The initial decision to let the musicians have the main say was crucial in the RIO book. Only then did conversations with the organisers and promoters follow. The interviews were not pre-planned or structured, making them very different from each other. Some delve into memory; others rely on diary entries or selected documents. The book offers an image of the cultural landscape, connections, relationships, political activities, and organisation in the second half of the 1970s. Not many such publications also offer personal stories, especially since we are speaking about a specific field of culture.

In the introduction, you mention that the voices of musicians and creators are often overlooked. How do the interviews in the book help correct that historical oversight and give us a better understanding of their work?

They are indeed most often unheard or overlooked. This decision may have been influenced by an event at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ljubljana, where I had studied painting. None of the classes satisfied me. Ultimately, I found the greatest joy in the small publications Likovne sveske, published by the University of Arts in Belgrade since 1971. Each volume brought conversations with famous visual artists, their own words, and original thoughts. There was no intermediary there, and that was liberating.

The interviews in the RIO publication are important because they help us understand the time and context of that independent production. Each written thought is worth its weight in gold, representing a fragment in a mosaic. Those were the times when a considerable amount of organisational inventiveness and ability was required. Aleks Lenard and Zorko Škvor have done a great job, and besides, the punk era was already at full speed.

The book focuses on three main bands: Begnagrad, Srp, and D’Pravda. What key elements connected these groups within the Slovenian RIO movement, and how does the book highlight that?

Begnagrad, Srp, and D’Pravda are distinct groups. They differ in working methods, dynamics, and the selection and merging of various cultural traditions, etc. In addition, they worked in different time frames. Begnagrad had two ensembles, with a gap in activity from 1975 to 1983. Srp was active between 1979 and 1984, and D’Pravda only for a year or so.

Each band has its own story and, to some extent, its social context. As for Srp, we moved from combining classical and repetition to freely improvised music, strongly influenced by American jazz (Art Ensemble of Chicago, Anthony Braxton, Roscoe Mitchell). We changed the usual stage performance, dramaturgy, and performativity and included small instruments. Then, we got involved in cooperation with theatres.

I’d love to hear your perspective as a musician and artist. How did you experience that time? After all, you were also a member of the band Srp.

In 1975, at the age of fifteen, I got a camera, and that’s when I took my first shots through my apartment window. Completely spontaneously. After 46 years, I realised that I was following the logic of sequential photography (everyday life, periphery, repetition, tonal reduction). At the same time, our first band was formed. I hadn’t owned an instrument yet but bought a second-hand bass guitar that year. Music was so important. That year, Buldožer released their first album, ‘Pljuni istini u oči,’ which shook up everything that had been made in the field of popular music up to that point. Ivan Volarič Feo’s legendary literary debut, Desperado Tonic Water, was released. Those were exciting times. We played our first concert in 1977.

The 2021 exhibition at the P74 Gallery, ŽIVALI HIŠE LJUDJE. Zgodnja dela (Animals, Houses, People. Early Works), highlighted my artworks from 1975 to 1980, which were unknown until then. The curator described them as delayed audience works (“zamujenega občinstva”). These pieces existed but had never before been exhibited. This is especially true for performances in public spaces, which I called actions without an event (akcije brez dogodka).

The book doesn’t just look at musical experimentation, but it also touches on the multimedia and visual creativity of these bands. Could you talk a bit more about the connection between RIO music and other art forms?

Bogo Pečnikar, Iztok Osojnik, Gojmir Lešnjak, and I were active in visual art, photography, experimental film, painting (scenography, graphic design), where we developed our visual language. Several members of the groups (Andrej Rozman Roza, Iztok Saksida Jakac, Gojmir Lešnjak) were also internationally active in other areas of art, including literature, theatre, and alternative street theatre.

In the book, you place special emphasis on Aleks Lenard. What led you to dedicate so much attention to him, and how does his contribution help illuminate the bigger picture of RIO in Slovenia?

Aleks Lenard was the leading promoter and key link between us. I met him sometime later. Let me emphasise that preparing the RIO book was a learning experience for me. I gained a significant insight into the histories of the movement and local groups. We musicians came from different generations and backgrounds and were musically connected to entirely different traditions. This brought about extraordinary diversity and variety.

So, Aleks Lenard was a key figure in developing Rock in Opposition in Slovenia. How did his interview influence the structure and overall direction of the book?

Aleks’s interview did not significantly influence the structure of the book. However, his text presents an important introduction, outlining the cultural context and the developments of independent music. Aleks used to travel, meet people, and connect with bands. He also regularly published articles in popular magazines that were not initially intended for experimental music. They published his texts regularly, which was quite surprising.

Lenard’s radio show, Untergrunt Molekula (Underground Molecule), was a pioneering project. How did his insights about the show’s impact and reception, which he shared in the interview, help shape your understanding of the context in which the Slovenian RIO scene was emerging?

I first read Aleks’s interview only while editing the book, so it did not impact my understanding of the context and movement.

Lenard played a crucial role in organising the first RIO festivals in Ljubljana. What specific details or anecdotes from the interview shed light on the challenges and significance of those events for the local RIO scene – and how did you incorporate that into the book?

From today’s perspective, it’s fantastic how the guys managed to organise public concert events so well with so few resources. The philosophy of belonging and solidarity, which is very difficult to find today, is also incredible.

One core driving force behind the RIO movement was resistance to the dominant music industry. What key motivations around this theme stood out to you, and how are they reflected in the narrative of your book?

Like elsewhere, the local music market in Slovenia has its own specifics and laws. The attitude towards experimental production in Slovenia was very conservative. There were no suitable concert venues in the city for such music, which required exceptional skill and ability to improvise. Finding an inn with an extraordinary garden in the centre of Ljubljana, which is also called Rio, was more than a success. There was virtually no access to recording studios, let alone to record an album. In fact, all this can be understood as a sophisticated form of censorship.

What challenges did you encounter while gathering material and information for the book, especially since this happened before the digital era and the Slovenian RIO scene has not been as well documented as other movements?

It wasn’t easy. At times, it was even funny because some of the notes were handwritten, in addition to photocopied articles and lots and lots of oral tradition. Everything had to be verified.

You and Igor Bašin Bigor conducted the interviews. What was the collaboration process like, and how did you split the work?

Igor and I got along very well. He belongs to a younger generation of popular and rock music connoisseurs. Our collaboration has been smooth and natural.

The book is bilingual, featuring both Slovenian and English. What led you to make that decision, and how important is the English translation for bringing more international attention to the Slovenian RIO scene?

That is our standard strategy. All of our publications are bilingual, whether they are more theoretical editions or monographs.

Following SOG (Design and Graphic Section), RIO: Rock in Opposition is the second publication in the SEVENTIES series. Can you share anything about upcoming titles or themes in the series yet?

In official art history, little is known about the Ljubljana Forum Association, which has operated on the Student Campus since the mid-1970s. The Forum was the most important organisation for promoting and presenting independent culture in visual art, alternative theatre, and music. SOG (Design and Graphic Section) was their workshop for young people, which successfully operated for twenty-one years. Still, no book has been published about it, and no exhibition has been dedicated to it.

This year, we are preparing a new publication that will present three excellent artists of the 1970s: Matjaž Hanžek, Dalibor Zupančič, and Slobodan Valentinčič. These exceptional creative personalities cover the underrepresented areas of visual poetry, performance, and experimental film.

As the book’s editor, what surprised or excited you most during the RIO: Rock in Opposition project? And is there a specific part of the book you’d highlight as a special key to understanding this important chapter in Slovenian music and cultural history?

I am very pleased with the cross-genre breadth, openness, and creativity of Rock in Opposition. It possesses an extraordinary creative energy. Additionally, I would like to mention that in April 2024, a study and archive featuring 55 recordings of experimental music from 1976 to 1988 was published on the SIGIC (Slovenian Music Information Centre) website, which also covers works from RIO artists. We owe a special thanks to the OM Production Museum and Bratko Bibič for this remarkable archive of mostly unreleased music.

What else currently occupies your life?

I like to play badminton.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Begnagrad (1981) | Bogo Pečnikar, Nino de Gleria, Aleš Rendla, Bratko Bibič, Tine Žitko (sound engineer), Boris Romih | Photo by Andrej Klančar

P74 Gallery Official Website / Facebook / Instagram

Tadej Pogačar Official Website

Aleks Lenard | The Man Who Brought Rock In Opposition To Slovenia