Älgarnas Trädgård | Interview | Dan Söderqvist

Älgarnas Trädgård emerged from the Swedish underground counterculture scene of the late 1960s, pioneering a unique blend of psychedelic and experimental music.

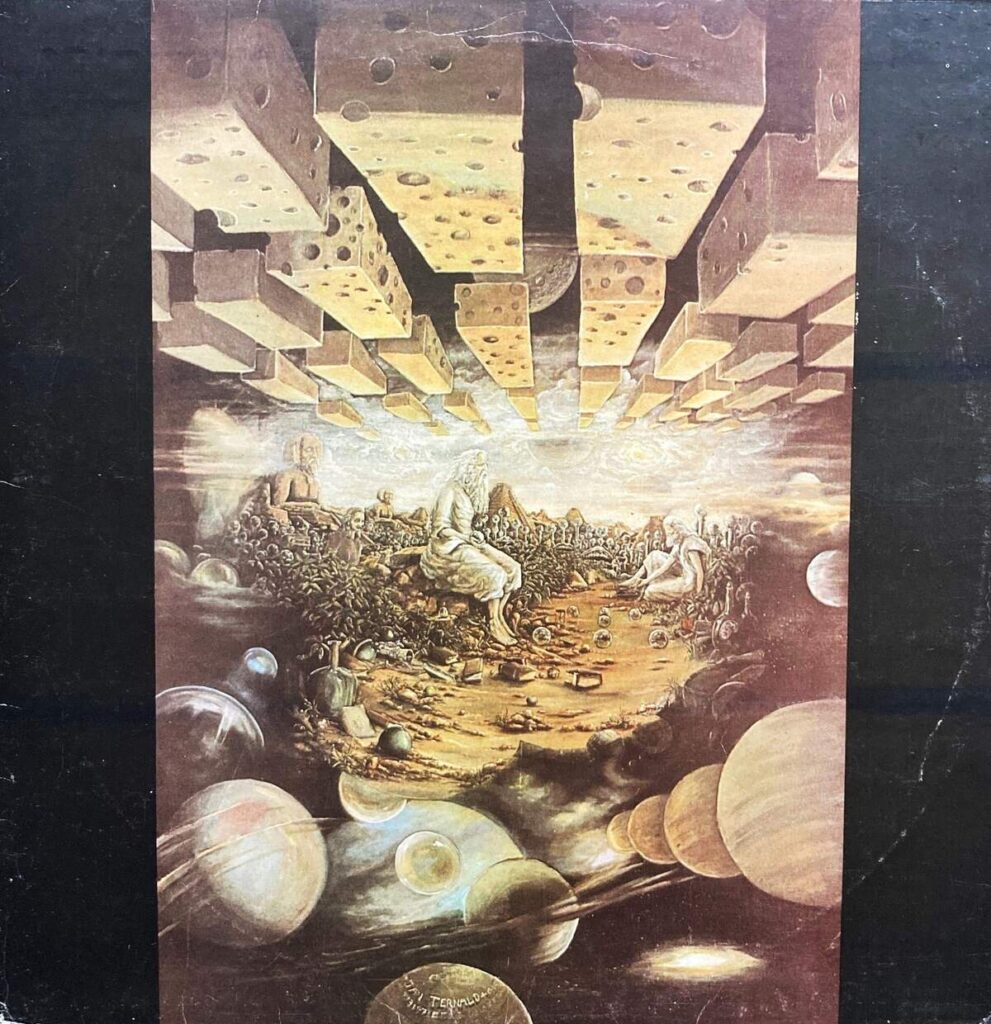

Formed in Gothenburg in 1969, their music defied conventions with intricate improvisations and a rich tapestry of sounds that included guitars, sitars, tablas, and homemade instruments. Their debut album, ‘Framtiden Är Ett Svävande Skepp, Förankrat I Forntiden’ (The Future is a Hovering Ship Anchored in the Past), recorded in 1970, remains a cult classic of the era. Known for their mystical and atmospheric live performances, Älgarnas Trädgård’s influence on the Swedish underground music scene of the early 1970s continues to resonate, establishing them as pioneers unafraid to experiment. In a recent interview with Dan Söderqvist, a member of the band, he reflected on their legacy and more.

“Engaging in long improvisations while drinking tea”

Would you like to share about your upbringing? Where did you all grow up? Tell us about daily life back in your teenage years.

Dan Söderqvist: I was born in Gothenburg in 1953. I was brought up in a newly built ’50s suburb that had almost a countryside feeling to it. It was close to nature and a few kilometers from the sea. Gothenburg was, at the time, a working-class city with large shipyards, the largest harbor in Scandinavia, and the car factory Volvo. I was the youngest child, growing up with three sisters. We lived in a small apartment, and I shared a room with two of my sisters. My sisters listened to Elvis Presley, so I heard a lot of music when I was a child. The big music experience, at the age of 10, was a live concert on Swedish television by The Beatles in October 1963. I was knocked out, and after that, I especially followed the English pop music scene. Bands followed each other: The Rolling Stones, The Who, The Small Faces… Three years later, I heard ‘Freak Out!’ by The Mothers of Invention, and once again, my young teenage mind was blown away. Gothenburg was a great music city at the time, and I had the opportunity to see bands like The Who, The Cream, Jimi Hendrix, and The Mothers of Invention as early as 1967. At the same time, I listened to the new psychedelic bands like Pink Floyd, The Doors, and Jefferson Airplane. My life was music, and through Frank Zappa, I also learned about classical music. I fell in love with Stravinsky, Webern, Shostakovich, and others.

Was Älgarnas Trädgård your very first band?

When I was 12 years old, I had a band called The Ox, named after a song by The Who. The band was a trio with me on guitar and vocals, along with a drummer and a bassist. We played a few gigs, mostly at family parties and similar events.

Can you elaborate on the formation of Älgarnas Trädgård and what the main idea behind it was?

Jan Ternald (or RF as he was known to me) and I have known each other since 1968, when we met in our home neighborhood of Västra Frölunda, Gothenburg. We listened to everything: Pérotin’s heavenly choirs from the 13th century, Messiaen’s heavy orchestral works, Captain Beefheart’s ‘Safe as Milk’ with its surreal lyrics, King Crimson’s endless string of chords, the beautiful acoustic Third Ear Band, Terry Riley’s minimalism, and above all, the psychedelic music of early Pink Floyd.

Sometimes we played our “dägga-däng-music,” crazy rhythmic sessions with acoustic guitars and hysterical giggles. ‘Trout Mask Replica’ was on repeat. Other times, we just sat and listened to the sounds slowly disappearing into space.

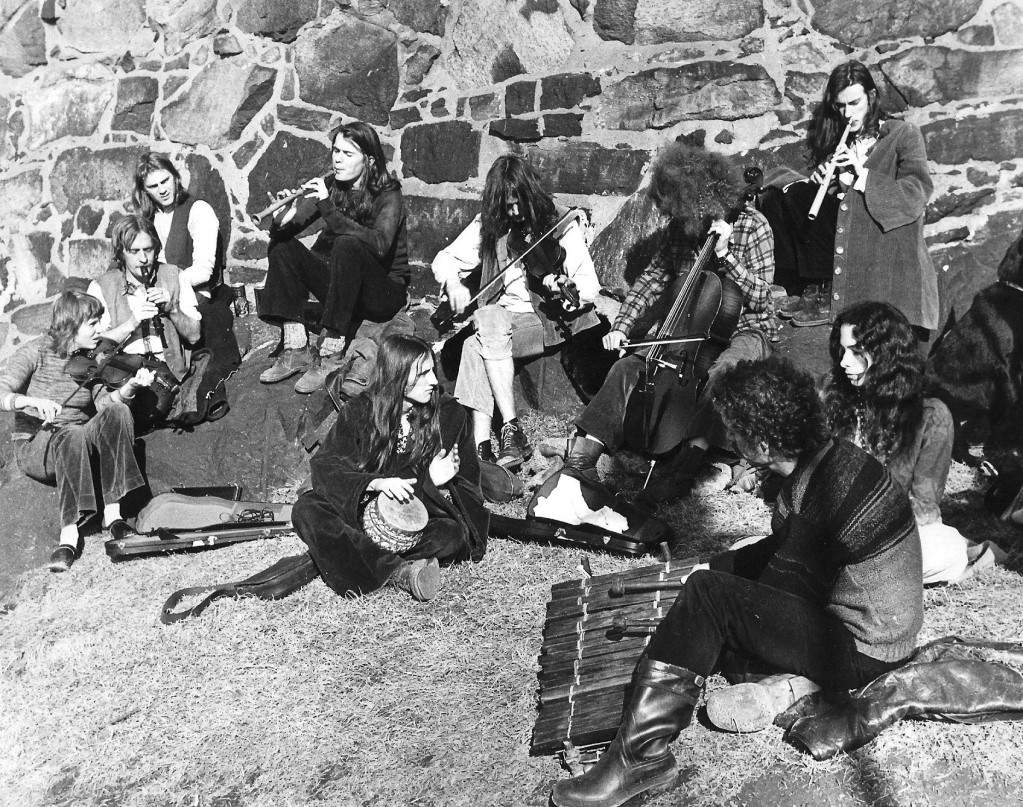

We often went into town to visit the Cue Club or Avenue 18. On the fourth floor, we had created a club that became a hangout for all the serious scatterbrains in town. It was there that we met Andreas and Dennis. At Burgårdens High School, RF met Mikael, who played with Sebastian. Eventually, we all started playing together. We used to sit in RF’s flat in Masthugget with guitars, violins, sitars, and tablas, engaging in long improvisations while drinking tea.

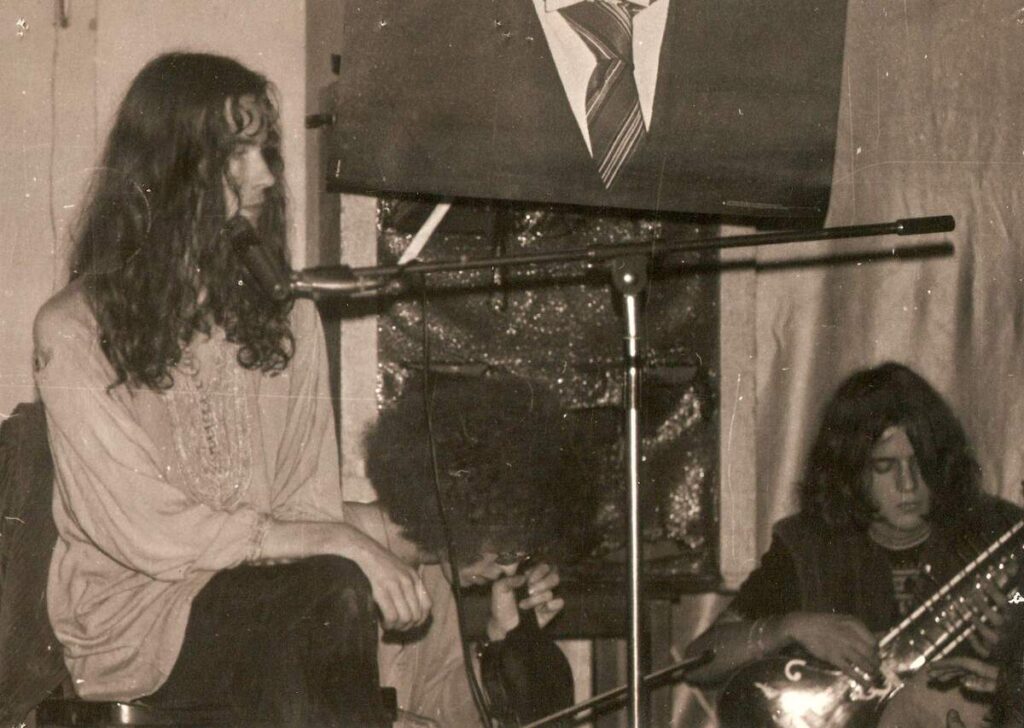

Our first public concert was around Christmas 1969 at Hagahuset in Gothenburg. At that time, we called ourselves “Innerst Inne” (Inside Within). Mikael’s then 9-year-old sister read from “The Artificial Paradise” by Baudelaire. In the spring of 1970, we secured a rehearsal room in Haga, where we would sit for hours, playing simple, repetitive melodies. “Two hours over two blue mountains with a coo-coo on each side, of the hours, that is.” It was a collective, creating in a way that I think was unique. We listened to each other and played with tones. We did not call ourselves musicians; we created music out of feelings. We experimented with getting strange sounds out of our instruments, started using amplifiers, and played with echoes. We went so far as to even drink tea with echo effects.

RF had built a couple of tone generators, painted in a psychedelic way. We constantly expanded our possibilities for new sounds, incorporating organs, mouth harps, and pedals. At that time, Dennis played drums with the band “All These Blues” and, in our opinion, was the best at it. He wanted to join Älgarnas Trädgård, and the band finally took shape. From the fall of 1970 to the second Gärdetfesten in Stockholm in 1971, we did several concerts in the basement of Hagahuset, which was decorated with mural paintings by RF. These concerts were musical installations, drawing inspiration from paintings by Hieronymus Bosch. We were ridiculously interested in early Renaissance pictures—the more madonnas, the better. Sebastian and I went down to Bruges and played monks. I wrote long poems about The Middle Age Galaxy.

What led to the contract with the Silence label? What’s the story behind your debut album, ‘Framtiden Är Ett Svävande Skepp, Förankrat I Forntiden’?

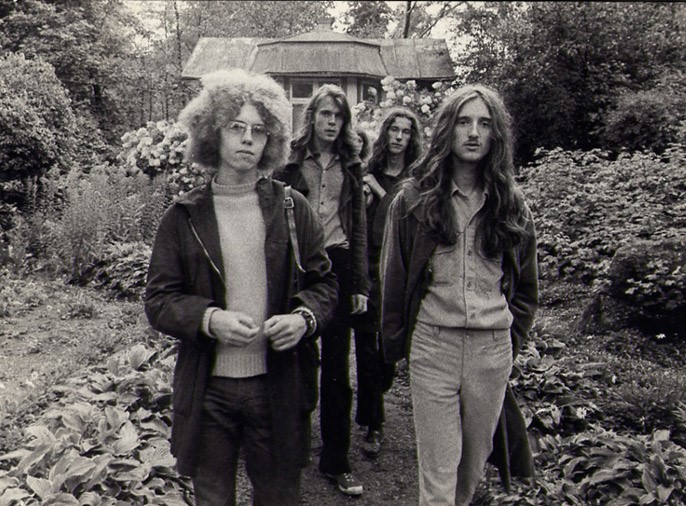

We were invited to play at the second Gärdetfesten in Stockholm in 1971. Dressed in medieval clothes with unbelievably long hair and our heads turned towards new worlds, we discovered that there were many other bands in Stockholm trying to explore and develop new kinds of music. We found ourselves part of a movement alongside Swedish progressive bands such as Träd, Gräs och Stenar, Kebnekajse, Fläsket Brinner, and more. While we felt alone in Gothenburg, in Stockholm we found our comrades.

The independent record label Silence recorded the festival, and Anders Lind from the label wanted to release an album with us! This was really cool! Imagine a bunch of experimental 16- to 20-year-olds about to make an album in a real studio. The album was recorded and mixed at Decibel Studios in Stockholm. It was recorded by Torbjörn Falk on an 8-track recorder and produced by the band. One can clearly hear that we wanted to try everything. We got our hands on the first Moog modular system that had just arrived in Sweden. We mixed medieval instruments such as zinks and rebecs, sound effects, church bells, fragments of both Bach and The Beatles, and improvised our way through the first album.

It can be added to the story that we lived and slept in the studio, and Torbjörn, who was engineering, worked around the clock. I think the process took a week to record and mix the album. “The Future is a Hovering Ship Anchored in the Past,” (originally: ‘Framtiden Är Ett Svävande Skepp, Förankrat I Forntiden’) as the record was named, was nominated for a Grammy award. One pity, though, was that we did not sound like that at all when playing live. A little consolation is that on the CD reissue released in 1995, there are two bonus tracks from live performances.

Did you like to experiment with psychedelics? Do you feel that that had any impact on who you became as musicians?

Psychedelics were definitely part of the equation, but I’m not sure if the impact was that significant after all. Experiencing music (or other things) on psychedelics can deepen your understanding of the universe, and I believe it’s beneficial to have had that experience when making and composing music. However, playing live while on drugs was always forbidden for me. I became a father at the age of 19, and after that, I stopped using psychedelics.

“Our live performances truly resembled a circus”

What venues did you play? Which bands did you share stages with?

We played alongside other bands in the same genre, such as Träd Gräs och Stenar, Samla Mammas Manna, Kebnekajse, and others. As far as I remember, we only played in Sweden. Over the next two years, we toured many festivals and also conducted two school tours funded by the government’s cultural department. Our performances took place in various venues, from dark dungeons to museums and castles. The band had grown, now incorporating a light show managed by The Spotlight Kids, and we even had our own bus. Our live performances truly resembled a circus.

Of course, we also honed our skills on our instruments. By the time we were ready to record our second album, the music had evolved to be more structured, heavier, and electric. However, the political climate was toughening, and polarization between us and certain political factions resulted in us being mistreated by some organizations and clubs that were supposed to support progressive and non-commercial music. They felt that our goal of “broadening the audience’s experience” wasn’t sufficient for admission to their venues. We faced a lot of criticism in town.

We began searching for a house in the countryside where we could establish a large artists’ community. We dreamed of creating a circus.

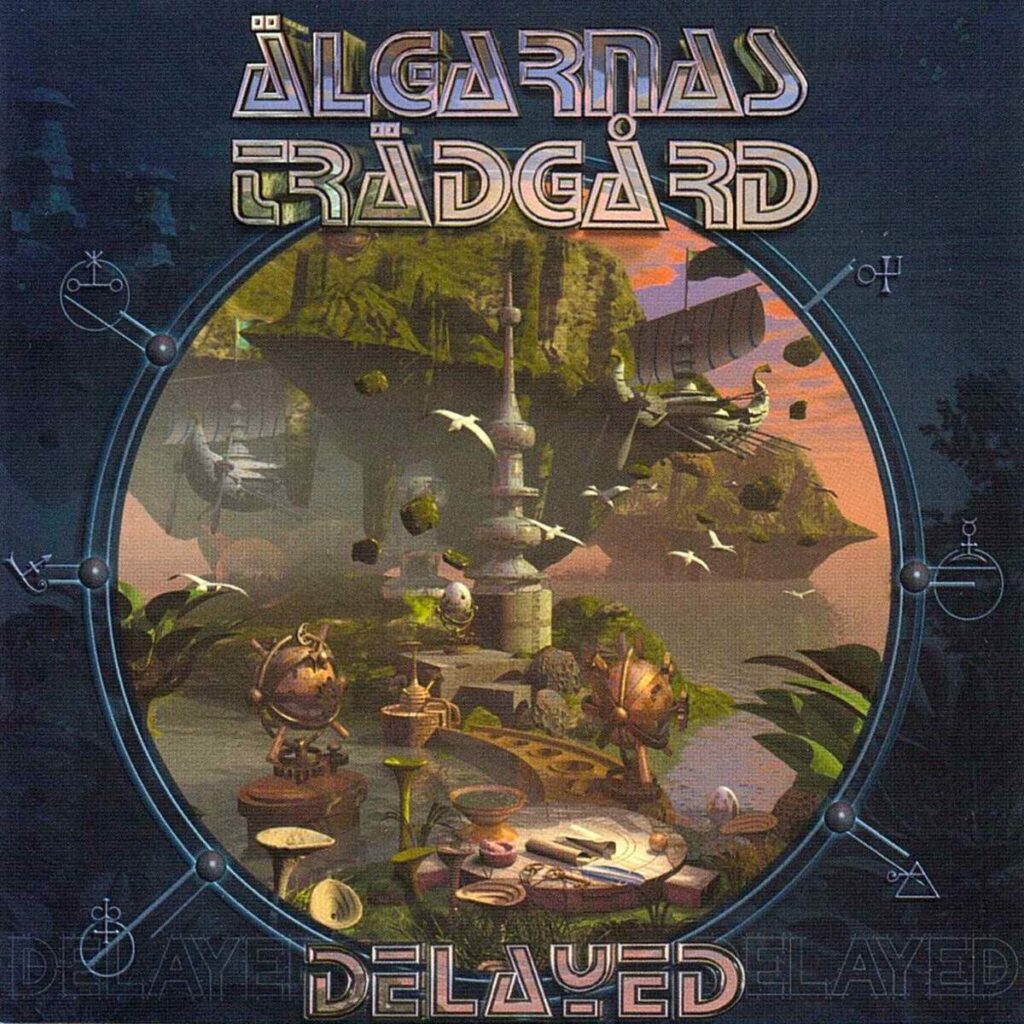

In 1974, you recorded another album which was released many years later as ‘Delayed.’ What were the circumstances surrounding it?

During the recordings of the second album, the band started to fall apart, both musically and socially. I became a father in 1973 and wanted to stay at home with my family. Dennis developed an interest in Indian religion and meditation, while Andreas wanted to explore the acoustic side of the music further. Naturally, there was a collision; one faction wanted to tour and play rock, while the other wanted to delve deeper into minimalistic musical borders. “I think we can take the tape loop from the end of ‘Min barndoms träd’ and put it on one whole side of the album,” was my opinion at the time.

When we mixed the record, we decided to disband, resulting in the album never being released. RF and Sebastian moved to Stockholm and started playing with Fläsket Brinner (The Flesh is Burning). Dennis joined the jazz group Mwendo Dawa. Andreas, Mikael, and I performed some concerts in 1975-76 under the name Älgarnas Trädgård. Later, I moved to the island Öland, and the elks were history.

What was the craziest gig you ever did?

I don’t remember; there were several.

Tell us about the amps, instruments, pedals, etc., you used.

For my guitar, which was an acoustic Levin with a pickup microphone, I used a 1960s Vox Fuzz box and a Dynacord echo unit. These were plugged into a homebuilt amp with a 12” loudspeaker, housed in a case I built myself. The sound was quite unique.

By the end of the 1970s, times were changing, and so was your sound. When did you stop Älgarnas Trädgård, and what led to the formation of Cosmic Overdose? How did Karl Gasleben (Ingemar Ljungström) and you get the idea to work on this project?

Karl Ingemar Gasleben and I had known each other since high school (Gymnasium). We had collaborated a few times in a small studio at school, but I was in Älgarnas Trädgård while he played in Anna Själv Tredje. Ingemar visited us on Öland a couple of times, and we started making music together, initially in the band UR, which was somewhat of a continuation of Älgarnas Trädgård.

During a Christmas holiday together, listening to new music like the punk band Wire and Bowie/Eno’s ‘Low,’ we felt inspired to create something new. Initially, it was just Ingemar and me with a rhythm machine. Little did we know that others around the globe had similar ideas. Over two years, we experimented with sound and the band’s format. At one point, there were five members exploring post-punk styles, sometimes purely electronic.

By the end of 1979, the band consisted of Ingemar, myself, and Kjell “Regnmakaren” Karlgren. We approached Silence Records and released our first album, ‘Dada Koko.’ Kjell left, and Tomas “Cyklon” Andersson joined, leading to the second Cosmic Overdose album, ‘4668.’ The band toured extensively and received offers to perform abroad, including in England. We supported New Order in Scandinavia and played two concerts in England in December. During this time, we translated the lyrics into English and changed the band’s name to Twice a Man. Our agent in England felt “Cosmic Overdose” sounded too hippieish and suggested several names, including Twice a Man.

You also joined Ragnarök in the 80s?

Actually, it was in 1979 that I joined Ragnarök for a tour and a theatre play. I also participated in their second album, ‘Fjärilar I Magen,’ both as a composer and musician. The plan was never to continue with Ragnarök as I focused on Cosmic Overdose.

What about the Butterfly Effect? Tell us about that.

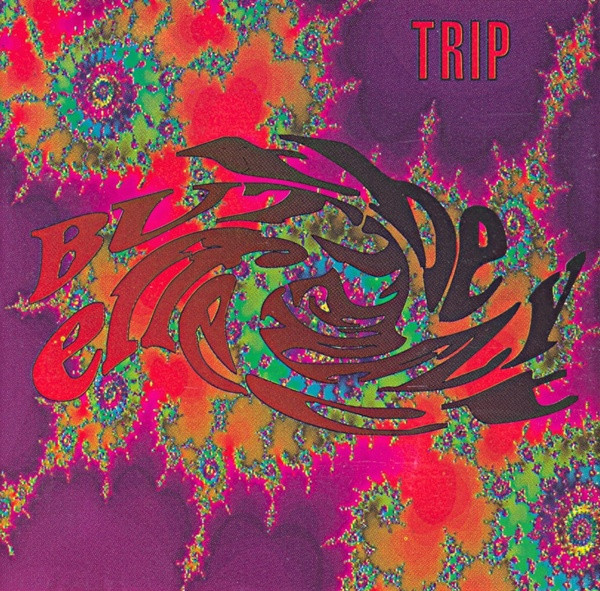

The Butterfly Effect was also a one-off project, featuring myself, Ingemar, Peter Davidson, and Zac O’Yeah (who was TAM’s light designer). The band existed between 1990 and 1992. We released one album, ‘Trip.’ It was intended to be a psychedelic pop band, mostly for fun, influenced by the Madchester wave and bands like Shamen, KLF, etc. I still love that band.

How do you see the Swedish counterculture, of which you were part, from today’s perspective?

I can clearly see the importance of the music from the early 70s and how it still influences musicians today. The movement was divided into two parts: one was political, where left-wing lyrics were paramount, accompanied by very traditional and sometimes dull music. The other part was instrumental and experimental, not just in music but also in lifestyle—embracing feminism, environmentalism, and a green way of living. It was political but not dogmatic. These two branches often clashed, which is regrettable because they could have been much stronger together.

Sweden in the 70s was a Social Democratic experiment that significantly improved people’s lives: holidays, equality, parental leave… The working class benefited greatly, and there was a belief in a brighter future. However, like many other countries, new liberal ideas took hold in the 80s, ending the era of successful social experiments.

Let’s conclude this interview with some of your favorite albums. Have you discovered anything new lately that you would like to recommend to our readers?

Three psychedelic-leaning Twice a Man albums I recommend:

Twice a Man – ‘Fungus & Sponge’ (1993)

Twice a Man – ‘Agricultural Beauty’ (2002)

Twice a Man – ‘Cocoon’ (2019)

I also recommend the collaborative album ‘Dan Söderqvist / Dark Flowers Awake‘ (2015)

Some old favorites that have had a profound impact on me and continue to inspire:

Pink Floyd – ‘Piper At The Gates Of Dawn’

Terry Riley – ‘A Rainbow In Curved Air’

The United States Of America (the band) – ‘The United States Of America’

White Noise – ‘An Electric Storm’

David Bowie – ‘Low’

Wire – ‘Pink Flag’

Joy Division – ‘Unknown Pleasures’

Massive Attack – ‘Mezzanine’

Newer music recommendations:

Chelsea Wolfe – ‘She Reaches Out To She Reaches Out To She’

Darkher – ‘Realm’

Zanias – ‘Ecdysis’

Dorothy Moscowitz – ‘Rising To Eternity’

The Smile – ‘Wall Of Eyes’

Rosa Anschütz – ‘Interior’

Thank you for taking the time. The final word is yours.

Make Love, Not War

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Älgarnas Trädgård | Photo by Marc Izikovitz

Twice A Man Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp

Cosmic Garden Project Facebook / Bandcamp

Kommun2 Official Website

Sound Effect Records Official Website / Facebook

Cosmic Garden Project | Interview | New Album, ‘The Green Reverb’