Art Zoyd | Interview | Thierry Zaboitzeff

Art Zoyd—a pioneering group that defies norms and embraces innovation at every turn.

Founded in 1969, their journey has been one of relentless innovation, blending rock, electronic, classical, and avant-garde influences into a sonic tapestry unlike any other. In this interview conducted in December 2023 with Thierry Zaboitzeff, a driving force behind Art Zoyd’s evolution, we delve into the creative process that has defined their groundbreaking work. Zaboitzeff’s expansive creative vision encompasses a wide range of genres, including rock, electronic, classical, and experimental, showcasing his diverse approach to composing music. Over the course of his career, he has consistently challenged conventional norms and ventured into uncharted sonic realms, leaving a profound and enduring mark on the landscape of contemporary music.

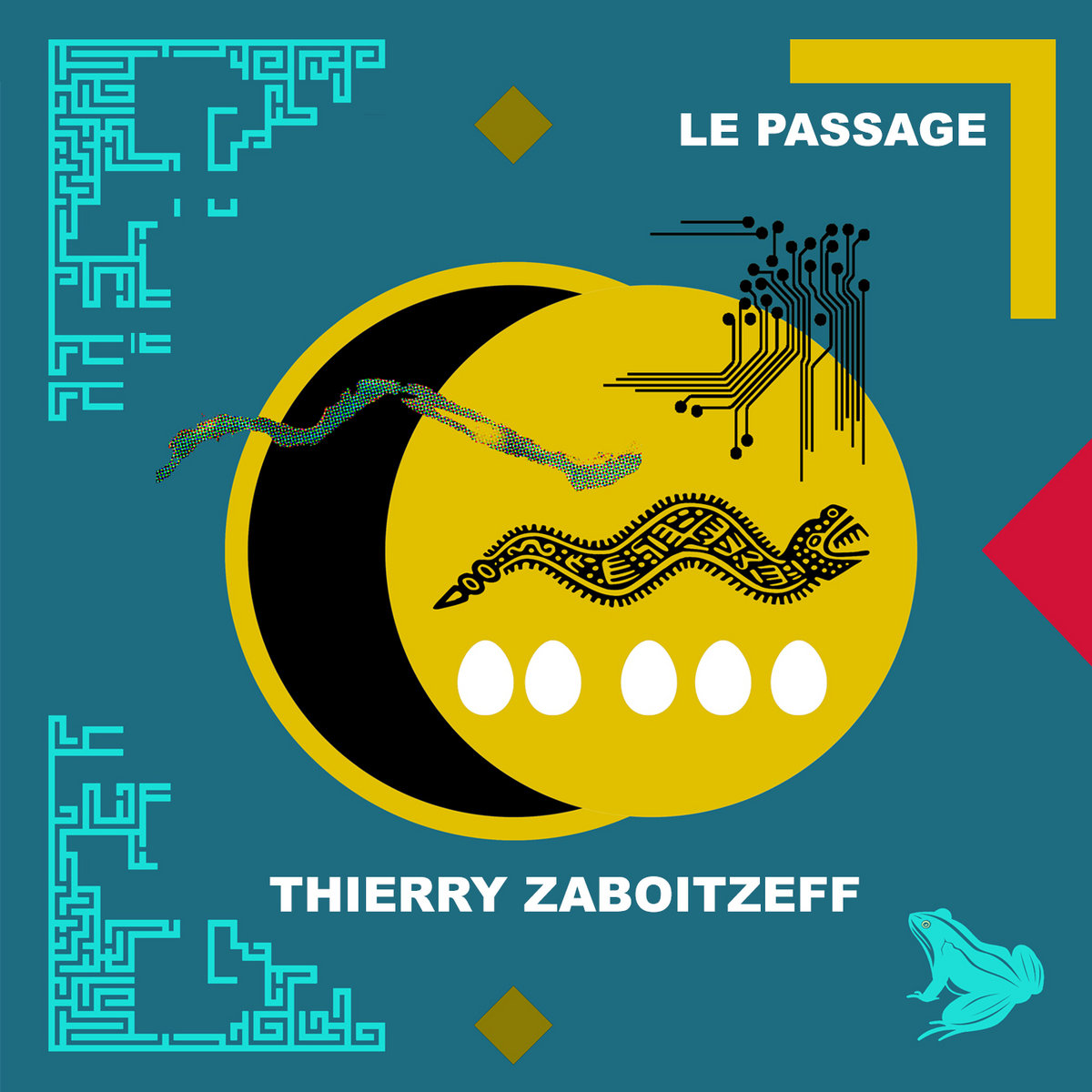

His latest album, ‘Le Passage,’ is an auditory odyssey meticulously composed, epitomizing a pinnacle in the realm of atmospheric soundscapes. Through a masterful orchestration of musical elements, Zaboitzeff beckons the audience into a transcendent domain where ethereal melodies seamlessly intertwine with haunting rhythmic motifs. This immersive sonic experience elicits a profound sense of transcendence and exploration, offering listeners a conduit to traverse the realms of imagination. Within the intricate tapestry of sound, delicate string motifs coalesce with pulsating percussion, creating a captivating mosaic of rich textures and evocative storytelling.

“I was more drawn to composers than instrumentalists”

’44 1/2: Live And Unreleased Works’ is such a stunning compilation, a must for any Art Zoyd fan. How much time and effort went into it, and how involved were you in the process?

Thierry Zaboitzeff: As a historic member (1971-1997), it was obvious that I should be invited to take part in this project, and my real involvement began in 2015 when we organized the Art Zoyd 44 1/2 anniversary concert and discussions began with Steve Feigenbaum of Cuneiform Records on the feasibility of such a box set. Gérard Hourbette had already started compiling all sorts of music that had already been published but in alternative or live versions, and which had not been released before. Then, I also suggested some previously unreleased pieces that I had in my possession for a very long time.

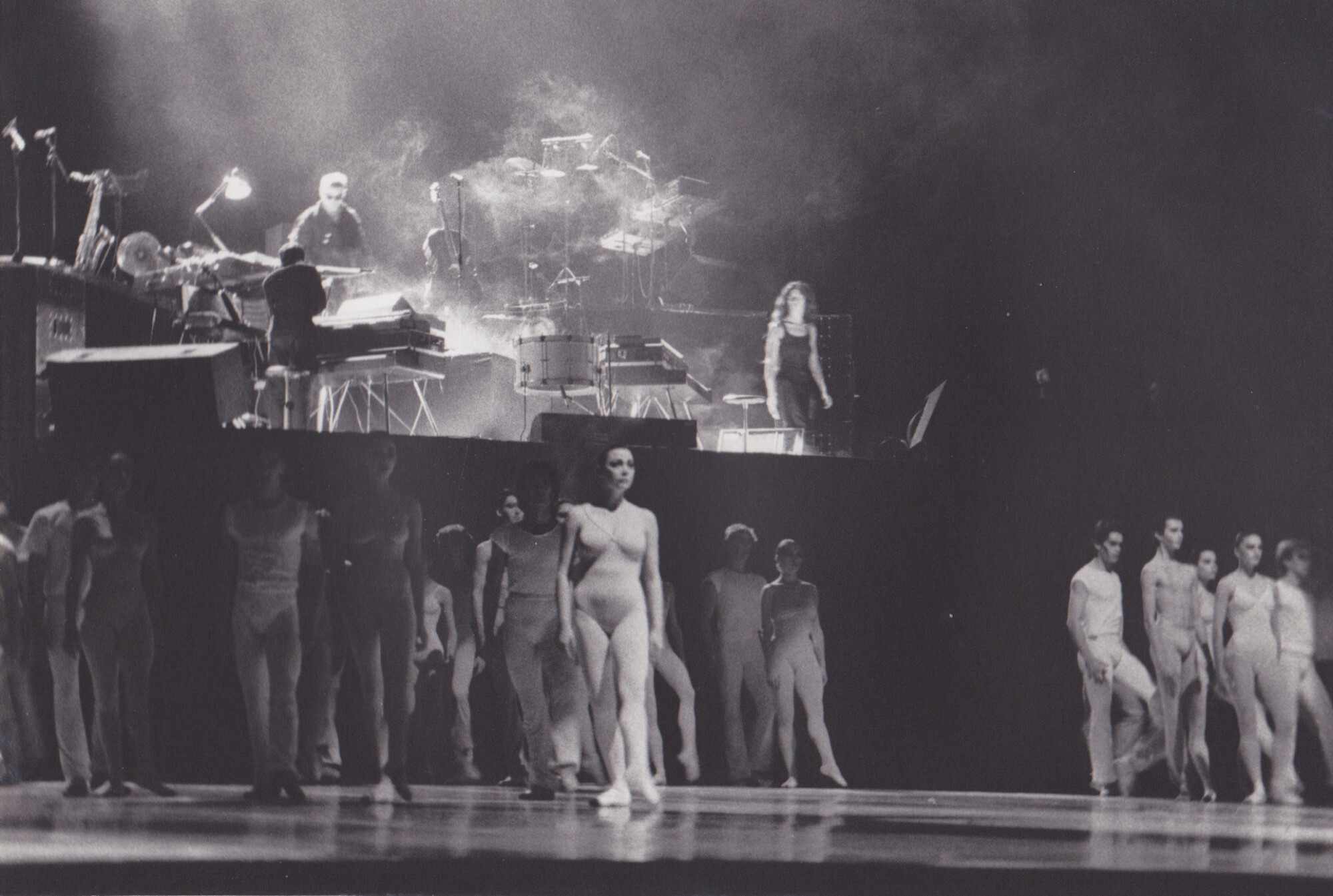

A little later, I took on the task of compiling and editing the videos shot by Robert Guillerault at the 2015 RIO (Carmaux-F), which had to be optimized and resoundtracked with the better quality live sound we had recorded on the mixing console. This live concert from 2015 appears on one of the two DVDs included in the box set. All this work was spread over two years, and the box set was released in 2017.

As a very active musician, what are some of the latest projects you’re involved with?

I compose a lot of music for the theatre and contemporary dance, and I also write for my own projects. Sometimes the two blend together and give birth to hybrid, offbeat works that take on a life of their own at the end of the process, by which I mean that elements composed for the theatre are often a starting point for an original composition that is sometimes far removed from its original form.

I’m currently working on a CD, ‘Le Passage,’ in which I’m reconnecting a little with my Artzoydian past, and I’ve invited trumpeter Jean-Pierre Soarez to play on three of my compositions. It’s due for release in January 2024 on physical CD and digital versions for the platforms.

Before this, I composed the music and soundscore for the editta braun company dance film LUVOS migrations.

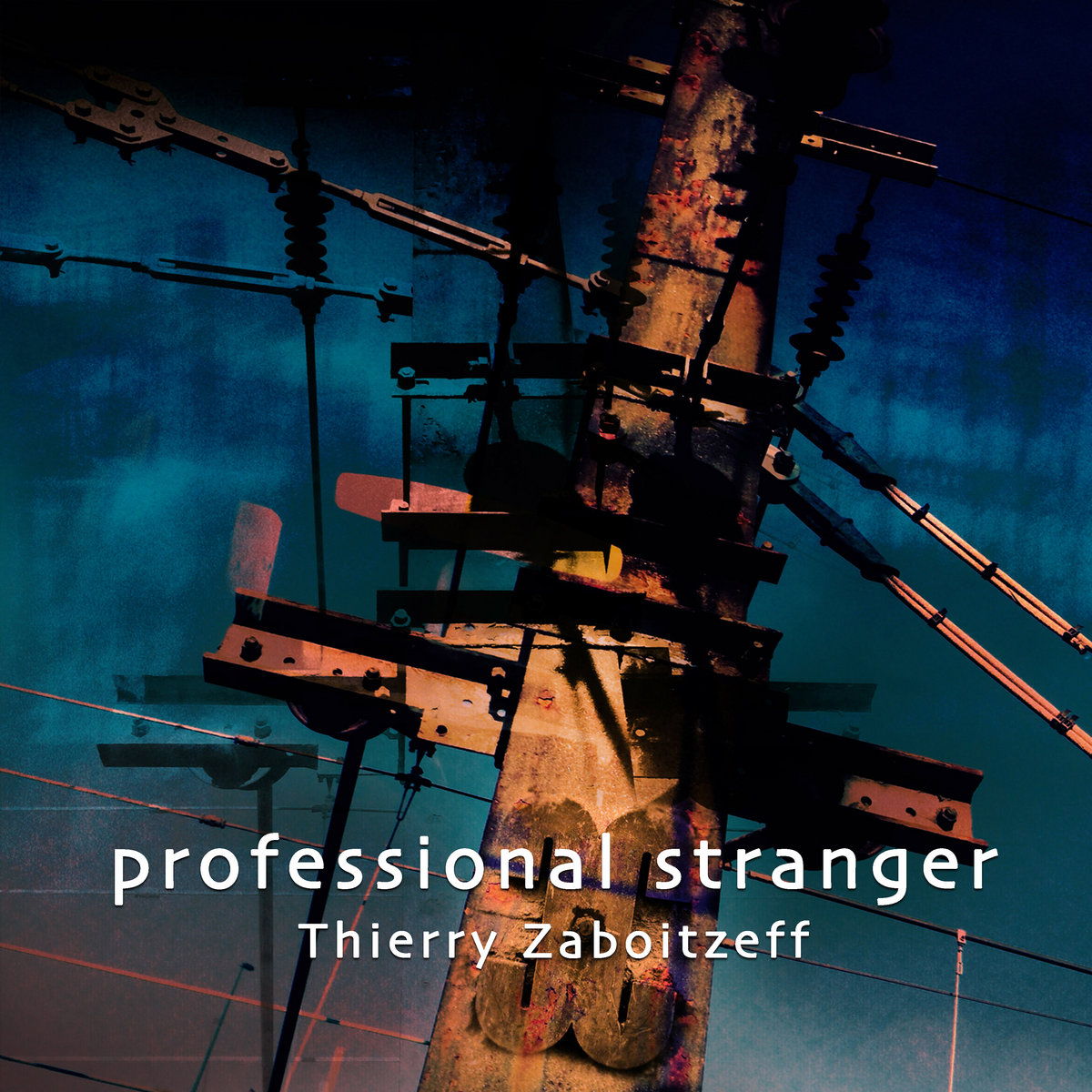

Tell us, what was your overall vision for your latest album ‘Professional Stranger’?

For years now, musically speaking, I’ve been consciously navigating towards genres of sound and music that awaken or inspire me, but never totally, and I end up forgetting them, moving away from them. This situation led me to say, during a conversation on the subject, that I’m a sort of professional stranger. This spontaneous expression made me smile and I ended up choosing it as the title of my album: ‘Professional Stranger’.

Initially, the project was based on music for a choreography, a staging of “long life” by editta braun company (A). A show for which I received a number of specific requests concerning soundscore, such as the omnipresence of an accordion that would act as a bridge between the different stages, but which would also be present in each of the pieces of music, whether electro-acoustic, jazzy or rock. For example, the cover of ‘Venus’. I thought it would be interesting to show these facets of my work, which is usually on the borderline between electronic music, contemporary music, and symphonic rock, and to add a touch of light by distancing myself from the precepts of RIO, Progressive Rock, and contemporary music – I had become the ‘Professional Stranger’ for the occasion.

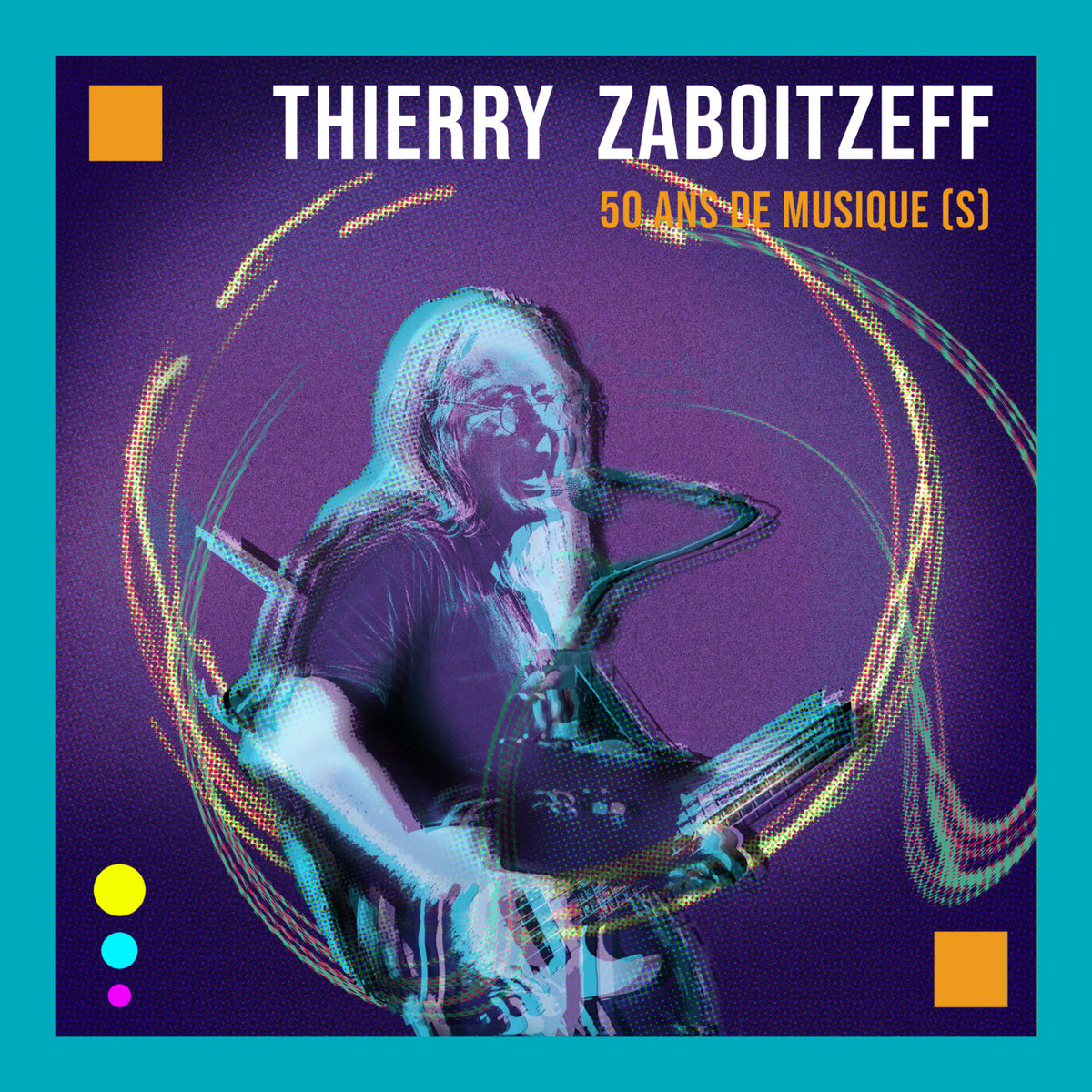

Isn’t it quite astonishing that we can discuss ’50 ans de musique(s)’? Was it difficult for you to decide what to include on this anniversary compilation?

Yes, it’s quite astonishing, I admit, and I’m both surprised and shocked by the time that has passed so quickly.

In fact, I went through a lot of “pain” to build this ideal playlist that I had to fit onto 3 CDs of around 72 minutes each. Obviously, I started by working in chronological order, but the result soon seemed artistically uninteresting, too didactic, and full of redundancies. After a number of equally unsuccessful attempts, I scrapped my playlists, not very happy with these constructions. Then, one day, by chance, I came up with the idea of completely freeing myself from eras and deciding that each CD (Vol) could be like a story told (only to myself, in truth…) in a very simple, very naive way, with tensions, moments of restraint, experimentation, letting go, battles, shifts in very distant geographies, thus forgetting the different eras and formations. In my opinion, the magic of this process worked. I wanted to be surprised, enchanted, assaulted, taken into imaginary theatrical scenes and after a few fine adjustments, I finally found the balance… The work that followed was very technical because in order to assemble tracks from different eras in the right order, I had to think about the overall sound of the boxed set. So, I had to remaster certain tracks, which meant that I could easily mix tracks from 1984 and 2020, for example.

What are some of the most important influences that shaped your own style, and what particular elements of their work resonated with you?

If I were to discuss the formative influences on my style, I would say that I was more drawn to composers than instrumentalists (such as Bartok, Stravinsky, Debussy, Ravel, Satie, Messian, Sibelius, Varèse, Luciano Berio…), to name just a few classical figures. I can’t claim direct influence from them, but I spent a lot of time listening to their work during a period when I was absorbing a great deal.

You see, I was quite young when my musical journey began, and like many teenagers, I initially idolized guitar heroes. However, my perspective shifted when I discovered Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention.

However, the true revelation for me occurred with Magma’s impact in 1970, when an extraordinary group drew upon its European roots to craft music that was completely novel, original, and compelling. I also held great admiration for Miles Davis… Oddly enough, as a bassist, I didn’t aspire to emulate any particular individual; the instrument served as one of many tools for constructing my compositions. Please don’t interpret this as arrogance or indifference, but rather as a reflection of my mindset.

What are some essential rock records you heard early on that influenced you as a musician? Do you think any of these influences transcended into the music of Art Zoyd?

‘Uncle Meat’ by the Mothers of Invention, ‘Third’ by Soft Machine, and ‘Kobaïa’ and ‘1001° Centigrades’ by Magma were all significant albums for me.

But can we still classify these artists strictly as rock?

For a brief period, we found ourselves drawn to Magma’s darker sound and unique arrangements, but gradually, we forged our own path and moved away from that aesthetic.

Maubeuge, the town where you grew up, was a heavy industrial city. Did the landscape influence the incredible atmosphere produced by Art Zoyd’s music?

Undoubtedly, the environment seeped into our sounds, our music, our lyrics; sometimes consciously, other times not.

During that period, the town and its surroundings felt heavy and dark to me, perhaps because I struggled to find my place there, and perhaps also due to the industrial decline of the 1970s, which affected the entire region. It’s challenging for me to analyze this situation and determine whether the industrial context alone contributed to the sense of darkness. I believe there were other factors at play, such as the political climate, the challenges faced by young people, a strong desire to rebel during those years when we sought to defy convention, and the emergence of artistic and musical movements independent of the mainstream entertainment industry.

Tell us, how did you originally meet Rocco Fernandez and Gérard Hourbette? What initiated the formation of Art Zoyd?

If you don’t mind, I’ll recount what I shared on this subject two years ago on my website, which is quite comprehensive and well-documented.

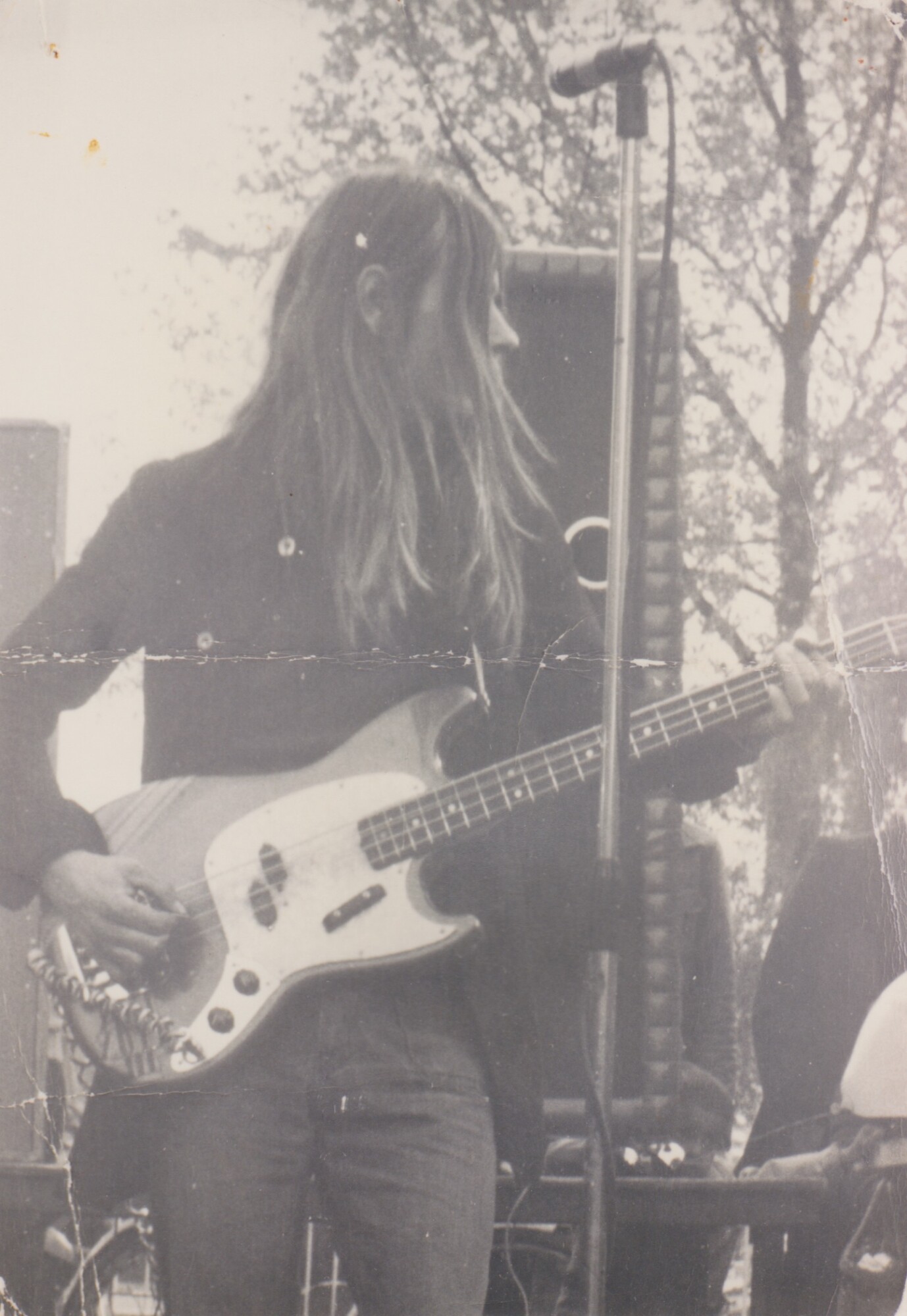

Maubeuge and Valenciennes (France), these two towns in the North of France were where it all began. Gérard Hourbette was studying violin and percussion at the conservatory, while I was on an apprenticeship contract in a printing shop. In my spare time, I desperately strummed the guitar on my own and sometimes in more collective circumstances, although not very interesting at the time. I used to go for lunch nearby in a young workers’ hostel that Gérard also frequented from time to time. I remember, some time before, having put up a poster saying that I was looking to meet a percussionist or other musicians… Our meeting was therefore quite natural, first over a cup of coffee and then with an instrument in hand in the minutes that followed…

That was the trigger, the sudden desire to do something together. We weren’t very fixed at the age of 16-17, but we had common desires and passions.

Gérard listened more to classical and contemporary composers (Bartok, Xenakis, Ligeti…), while I was into experimental and progressive rock, which wasn’t yet called so at the time (the very first Pink Floyd, Soft Machine, The Mothers of Invention, King Crimson, Amon Düül II…).

Very quickly, we launched into crazy electro-acoustic improvisations: electrified violin/twelve-string guitar, all passed through the mill of tape echo chambers and spring reverb. Nothing could stop us anymore, so we had to organize our first concerts (hall rental, ticketing, flyer and poster printing) and get people to come and see our thunderous improvisations. We organized two concerts in Maubeuge, one at the Salle Sthrau, the second at the young workers’ hostel where Gérard and I had first met (Foyer Sangha).

In the weeks that followed our first concert, a friend and bass player (Guy Judas) joined our crazy adventure and joined in the improvisation, this time with a bass – Class!

On an idea of Gérard, our group was baptized Rêve 1 and the title of our future concerts would be: “Voyage towards Kadath,” inspired by a novel of H.P Lovecraft.

In the summer, we decided to take a break and travel to the south of France to stay with friends I had met on an epic trip to Corsica where I lived and slept on the beach. I broke my contract with the printing company and decided on another destiny far from normality. I knew nothing of life, of the difficulties we would encounter later on, but youth and curiosity were our strength. For this short stay in the south, we took our instruments with us, which helped us financially because we played here and there on the terraces and other busy places. Very quickly, we got tired of this hippie life and decided to return to the north and to consider our future in music more seriously. As soon as we returned, we resumed our thunderous improvisations, still in trio.

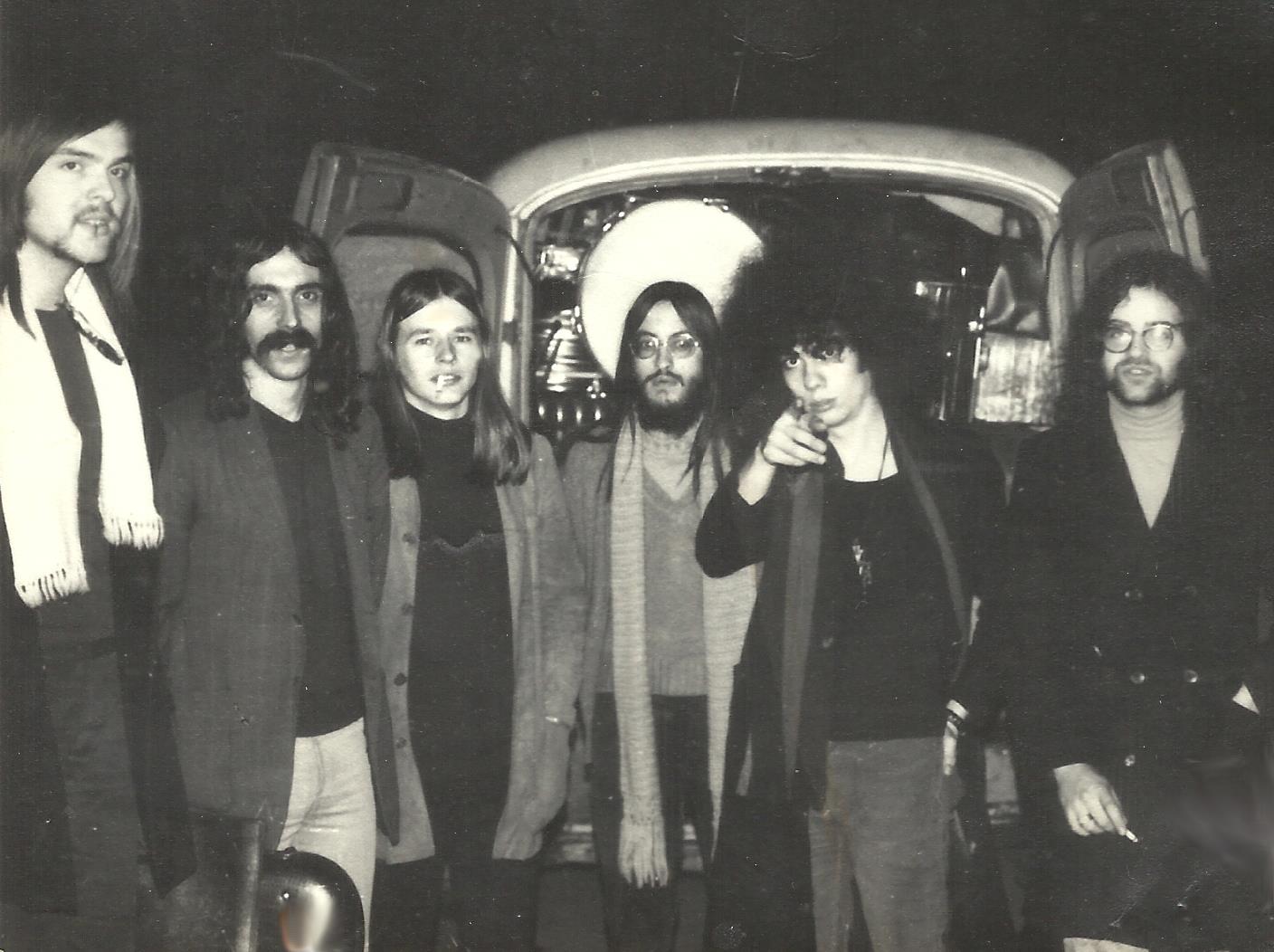

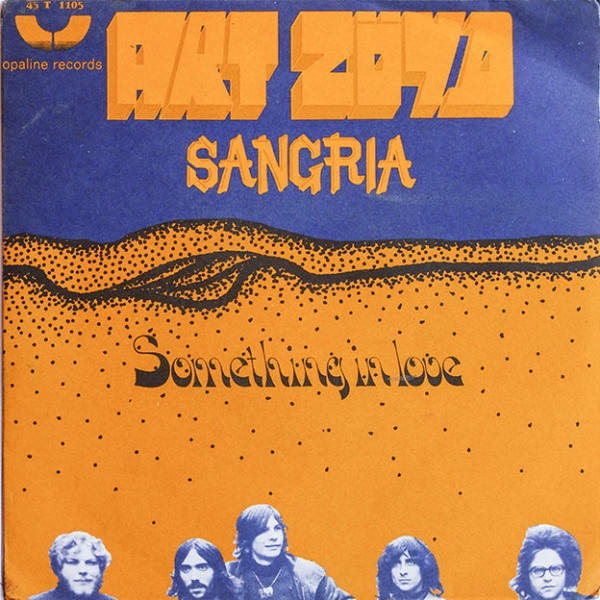

I don’t remember exactly why Gérard had to go to a music shop in Valenciennes (to repair a violin microphone or something else?) As soon as he entered the shop, with his violin under his arm, the conversation started quite quickly with Rocco Fernandez and other Art Zoyd musicians present that day. Exchanges were going on and intentions of collaboration were slowly emerging, so much so that Gérard returned the same evening to Maubeuge in the company of Rocco and another member of the band (Serge Armelin?) in their superb van (Ford Transit) put at their disposal by their record company at the time: “Opaline Records – Chant du Monde” following the recording of their first single: ‘Sangri’ / ‘Something in Love’.

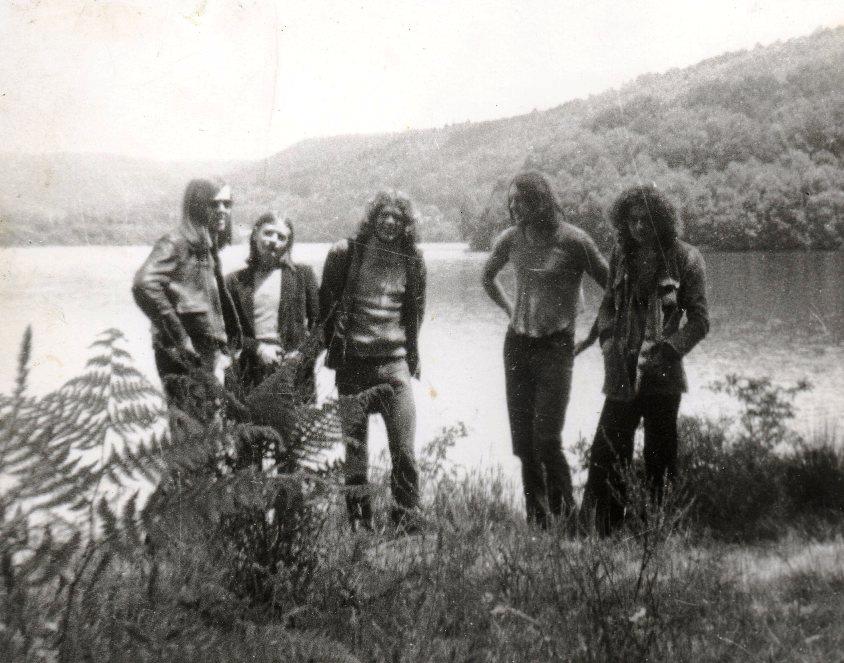

We were quite impressed at the time. Then naturally, after the usual introductions and some buttered toast soaked in coffee (our only dish of the day), we all gathered in Gérard’s parents’ cellar, where we were rehearsing, for a “Boeuf” like we had never experienced before. In my distant memory, there were not enough instruments to really play together, we exchanged, we tested each other and the current passed very well. Rocco Fernandez (a look-alike of Frank Zappa), Serge Armelin (?), Guy Judas, Gérard Hourbette, and myself were present that evening. A few days after this magical evening, we met again (Rêve 1: Gérard Hourbette on violin – Guy Judas on bass – Thierry Zaboitzeff on 12-string guitar) in Valenciennes to join the Art Zoyd group at the invitation of Rocco Fernandez.

We thus became true “ZOYDIANS”.

The group will then become Art Zoyd III.

What kind of music did you play at the very early period of the group, before releasing any album?

The repertoire was very Jazz-Rock à la Zappa, very structured but leaving plenty of room for improvisation and solos (guitar, saxophone, violins, drums…). This gradually changed, and the songs became harder, less jazz-oriented, and more rock-oriented, until Rocco left.

When Rocco Fernandez left the band, a new chapter started. Do you agree?

Yes, I completely agree. As I explained in my answer to the previous question, Art Zoyd’s music underwent some fundamental changes at the end of the Rocco Fernandez era, on his initiative and that of Gérard. It became more structured, tighter, more serious, and also more humorous. Unfortunately, in 1975 Rocco informed us of his intention to leave Art Zoyd. Bored and tired, he wanted to move on to something else. I have to admit that in the weeks that followed this decision, Gérard and I were cautious, not really knowing which direction to take. Jean Pierre Soarez (trumpet) had recently joined the group, as had Franck Cardon (violin), while Jean Jacques Reghem (drums) would stay on for a while longer. Little by little, still following in Rocco’s footsteps, our approach to composition and performance on stage took a very particular and original path as Gérard and I gradually took over the group’s destiny.

The rest will be contained in my answer to the following question.

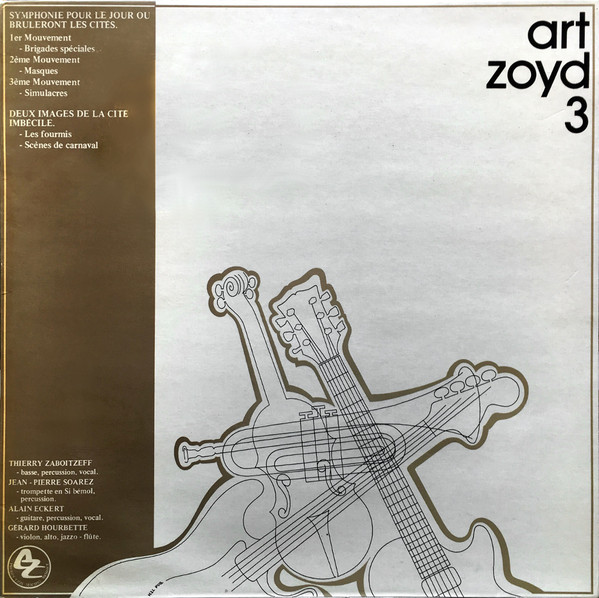

What’s the story behind your debut album, ‘Symphonie pour le jour où brûleront les cités’? Where did you record it? What kind of equipment did you use, and who was the producer? How many hours did you spend in the studio?

Until 1975, Rocco Fernandez was the group’s composer. Gérard and I had a few ideas, but it wasn’t the right time yet, especially for me… Rocco would compose instrument by instrument during our rehearsals, and in that context, everyone could contribute with their own know-how and personality. We kept up this approach for some time after his departure, and our 1976 repertoire and album ‘Symphonie pour le jour où brûleront les cités’ were born partly in this spirit, with the difference that Gérard began to present us with his sketches, which soon became ‘Brigades spéciales’ – ‘Masques’ – ‘Simulacres,’ compositions that were also edited collectively. We also adapted Rocco’s compositions, which became ‘Scènes de carnaval’ and ‘Les fourmis’, in more concentrated, condensed versions.

They were re-orchestrated without drums a few months later. We were often very irritated by having to constantly move musically between the regular and systematic pulsations of the drums and percussion. It was from this reflection and desire that an Art Zoyd without drums was born. As a result, depending on our aesthetic at the time, we could assign very different roles to our instrumentarium (two violins, a trumpet, and an electric bass): sometimes one was percussion, the other harmonic, and so we changed roles according to our desire for arrangements in our compositions. Our sounds gradually moved away from the traditional framework of a jazz-rock band, evoking more theatrical and cinematic atmospheres and flirting with the colors of 20th-century classical music. And so the foundations were laid for our first album, ‘Symphonie pour le jour où brûleront les cités’. At the same time, we met Michel Besset, a concert and tour organizer in southwest France. We struck up a friendship, and he became the producer of our first album (Symphonie…), which we recorded from August 30 to September 9, 1976, at Studio Tangara (François Artige and Jean-Pierre Grasset).

The technical situation was rather peculiar: we couldn’t do any re-recording, or have individual tracks for each instrument. The tracks were divided into the shortest logical sequences possible, and we recorded them all together. If there was the slightest mistake or misinterpretation, we (all) started again until we had the perfect take. The whole thing was put together and glued together. It’s probably this practice that gave this first album its distinctive sound. A huge amount of stress combined with a mix of cigarettes, coffee, beer… Cigarettes, coffee, beer… Cigarettes, coffee, beer… Cigarettes, coffee, beer… Screaming… Laughing fits…

“We wanted to preserve and develop the energy, electricity, and sonic power”

You had some very interesting concepts going on, for instance no drummer. As Gérard Hourbette said in my interview: “The idea was also to do without the song and the singer in the ordinary sense unavoidable in so-called rock music. The second idea was also to banish the “short” formats of rock and invent forms closer to the classical music of the twentieth century as the standard formats of the same rock, which for us bogged down in the “commercial” way. I would love it if you could elaborate on that and your own perspective on it.

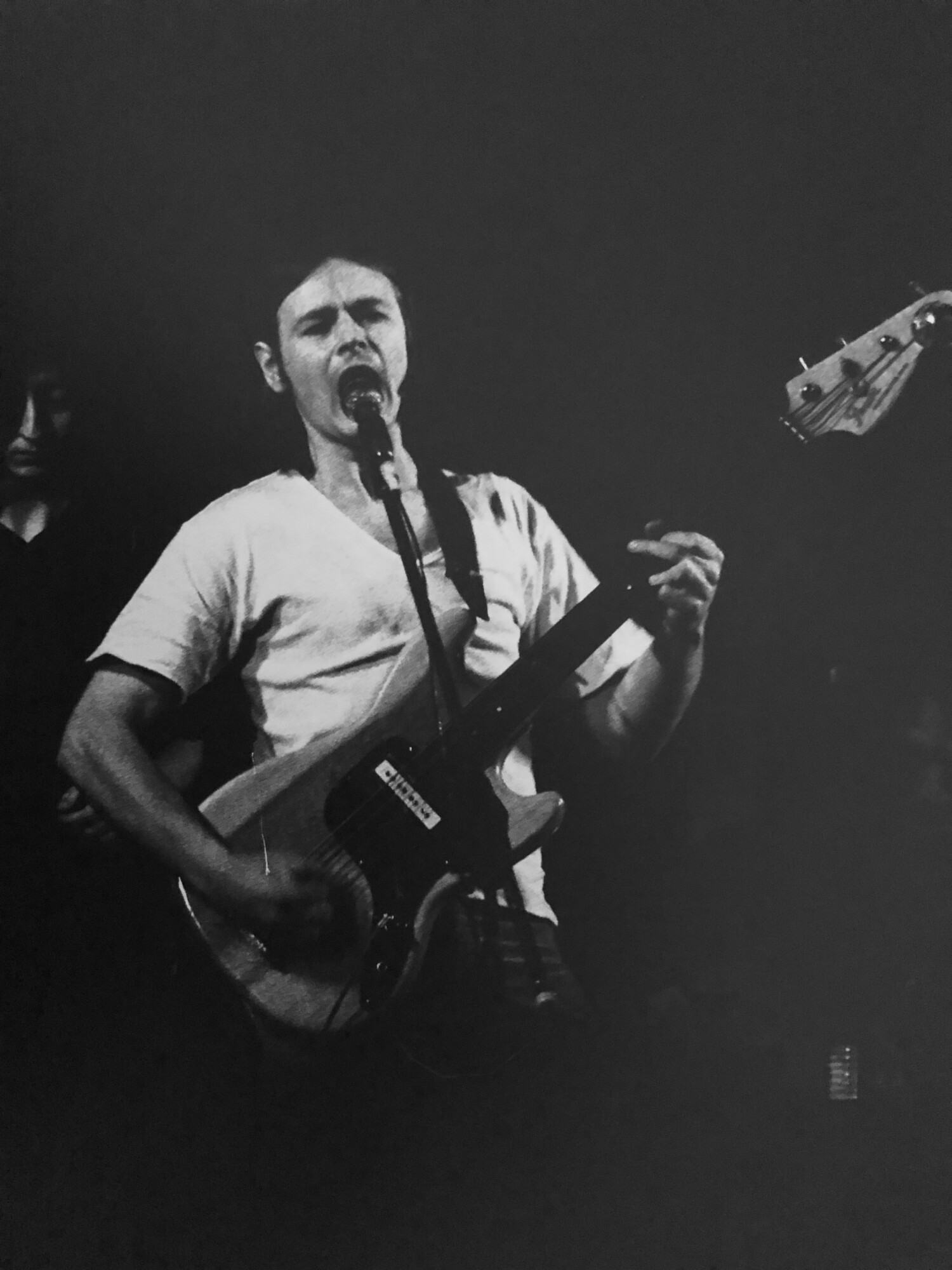

It’s a point of view and a concept that Gérard and I totally shared at the time, as we had implemented the process together. I have nothing more original to add, at the risk of being redundant. However, I could mention that, while we felt closer to the forms of 20th-century classical music, we wanted to preserve and develop the energy, electricity, and sonic power of rock within this unusual formation (an electrified quartet: guitar, violin, trumpet, and bass).

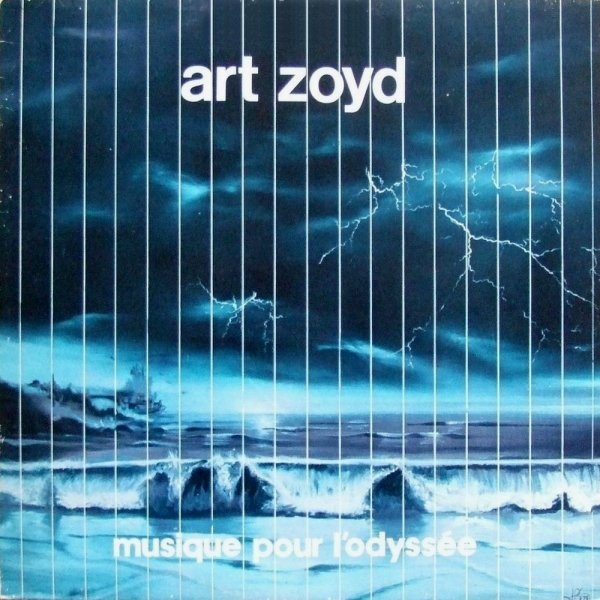

And this brings us to ‘Musique pour l’Odyssée’. When listening today, what memories come to mind?

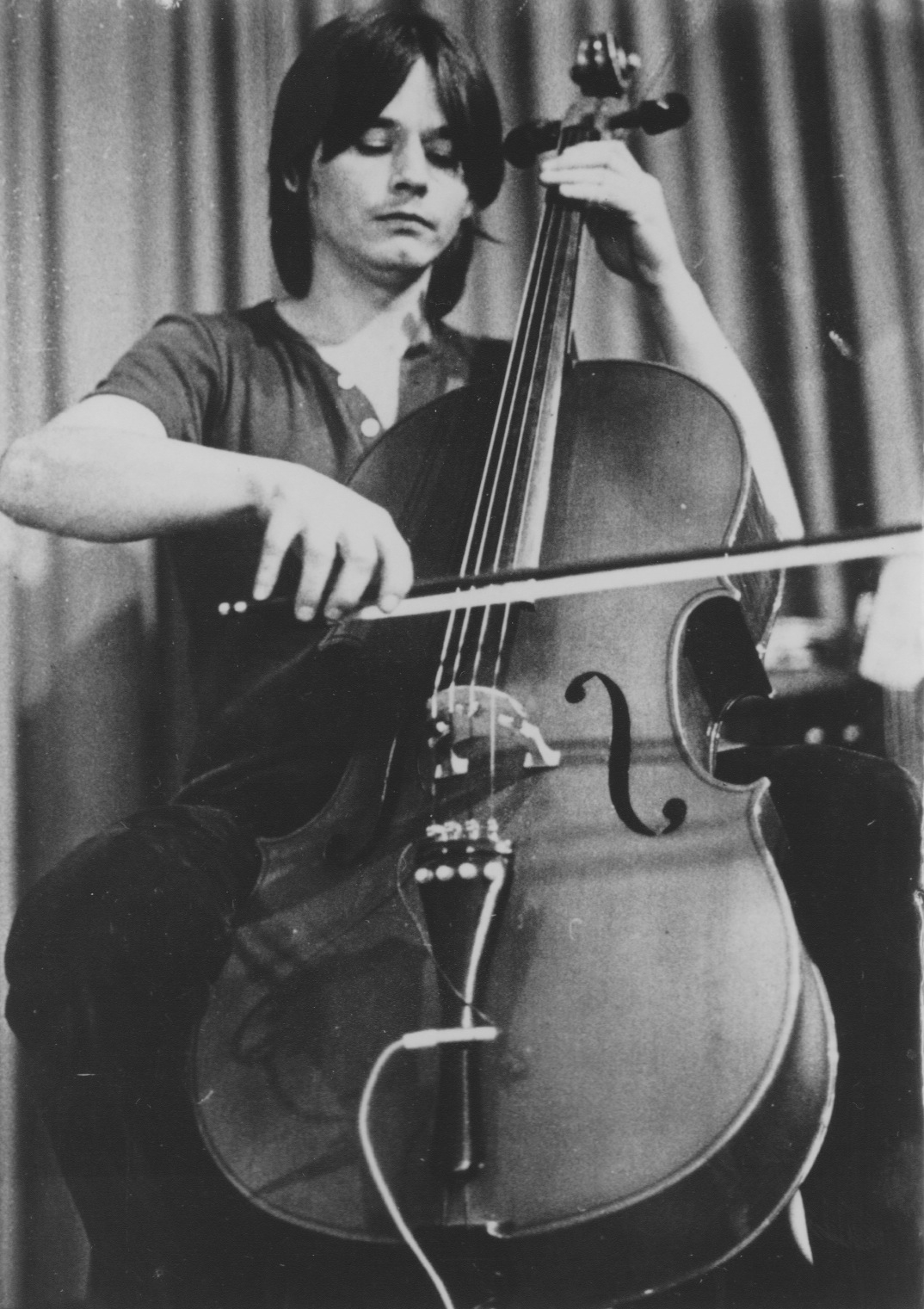

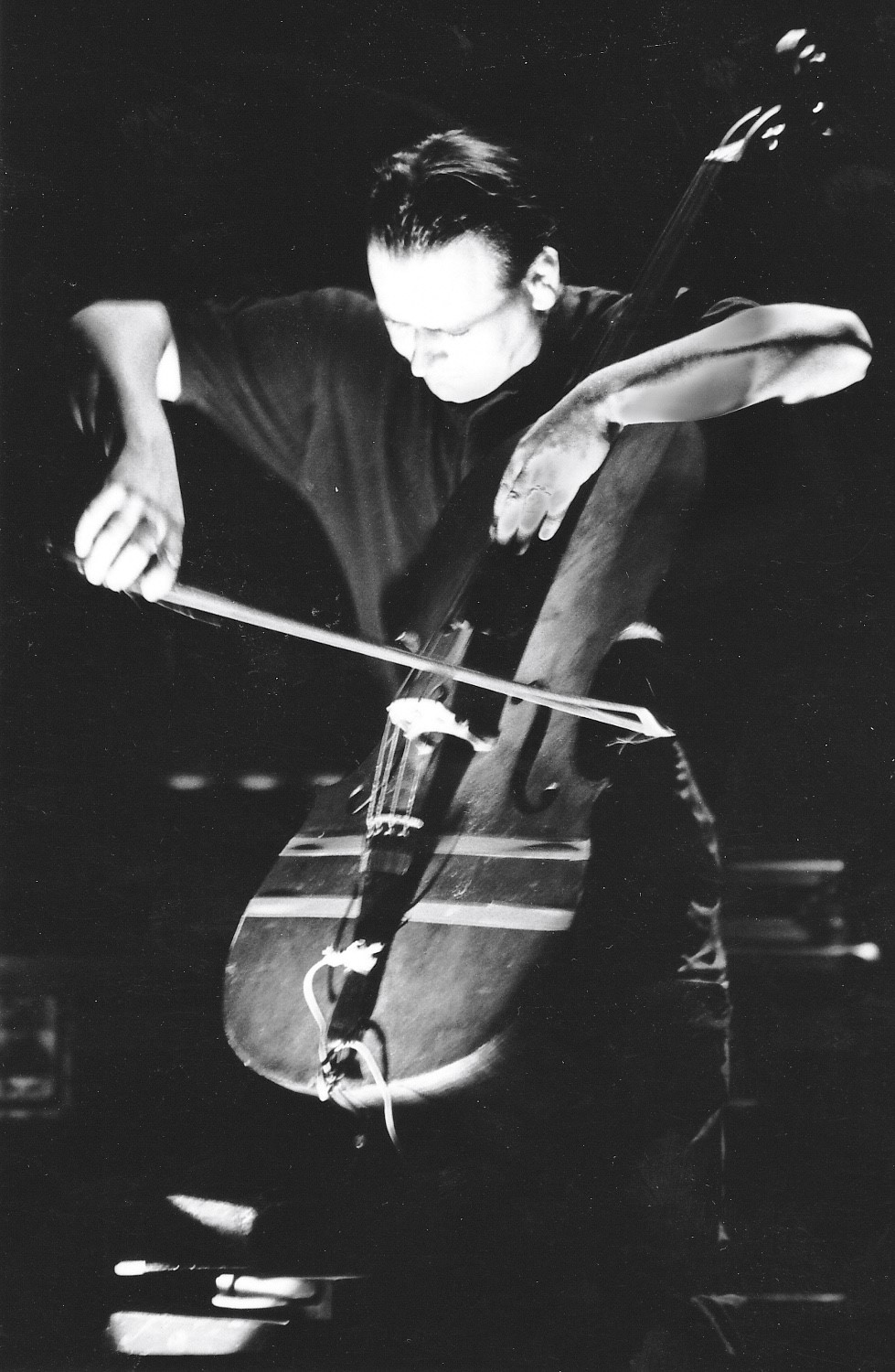

As with each forthcoming album, we were in search of renewal and aimed to gradually move away from the somewhat abrupt “symphony” sequence towards broader sounds. On a personal level, this was a significant moment because ‘Musique Pour l’Odyssée’ gave me the opportunity to present my first composition for Art Zoyd, ‘Bruit, Silence – Bruit, Repos’. But beyond that, in general terms, our sound was evolving, and I realized that my dry electric bass tone alone couldn’t fully contribute to this transformation. So, I decided to learn the cello, starting with the basics, to better integrate with our new orchestrations. This was especially important in tracks like ‘Musique Pour l’Odyssée’ and ‘Trio – Lettre d’Automne’, where the string sounds would sometimes be echoed by echo chambers. This expansion broadened the spectrum further, giving Art Zoyd’s sound and music a new dimension. Additionally, we added bassoon, oboe (Michel Berckmans), saxophones (Michel Thomas), and percussion (Daniel Denis). It was indeed a big moment and a big change for us.

How do you recall the early touring years of the band?

There are numerous memorable stories to share on this topic, and I invite you to visit the linked pages to gain a more personal insight into what life was like on tour with our band.

What would be the craziest gig you ever did?

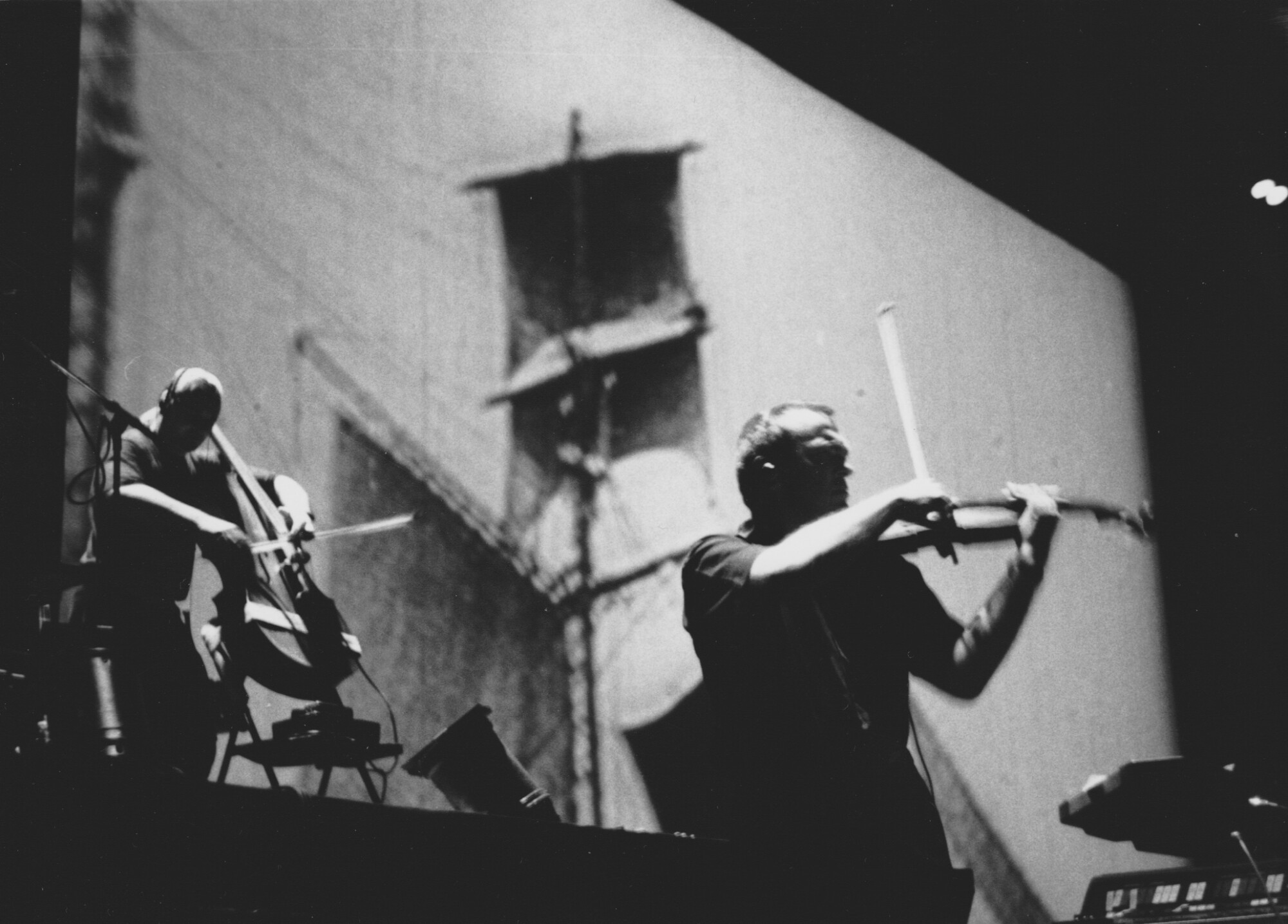

It was with Art Zoyd in Stockholm (S), in 1990. We gave our film-concert Nosferatu on a giant screen installed against the façade of the town hall in front of 30,000 spectators. The band was positioned on the roof of the building just above the screen. I still don’t know what the audience’s reactions were because we were so high up in front of this compact crowd… But I think the magic between this cult film and our music worked because the crowd just kept getting bigger and bigger and staying bigger and bigger – very impressive!

Is there any unreleased material by Art Zoyd or related projects?

As far as I know, and as far as I’m concerned, no! Those that were in my possession were reissued as they were in ‘Art Zoyd 44 1/2,’ or those that were waiting in my boxes were arranged differently and can be found here and there in my solo discography, sometimes in unexpected forms.

What kind of records have you been listening to lately?

I’ve been listening to a lot of Jon Hassell’s albums lately (‘Fourth World, Vol. 1: Possible Musics’ / ‘Listening To Pictures’ / ‘Flash of the Spirit’…), and these music and sounds keep me in a very particular state, quite far removed from what I produce, it seems to me. Strangely enough, at the same time, I’m listening again to quartets by Béla Bartók and Miles Davis from the ‘Bitches Brew’ era. But I work a lot, so time to listen to music is rare and precious. There’s listening for pleasure, and the artists mentioned above are part of that. And then there’s what I’d call documentary listening, which is very rich in diversity (jazz/free music/improvisation/ethnic/contemporary music/progressive rock/electronic music…).

Thank you for taking the time. The final word is yours.

You know, I’m very honored, very proud to still be talking about Art Zoyd today. We created so many things together, Gérard Hourbette and myself, along with all the musicians who supported this project. However, in 1997, I left the group, and since then, we each continued to propose projects and music on our own. Gérard passed away in 2018, and a few months before that, we had regular exchanges. We were both a bit disappointed that the public or the fans still wanted to see us and hear us as in the past, sometimes overshadowing what we were both doing separately in the present. Even separately, we were always pushing our own musical language further or exploring new territories.

I’m not unaware that this phenomenon can be linked to an aging generation with its musical memories of youth, but it remains a little frustrating for active composers that we still are, or at least that I still am since Gérard has left us. I had this feeling in my heart, and your interview is an opportunity to share it. But don’t worry, I’m not bitter, and I’m always aware of what’s going on, with my ears open to anything that might help me bounce back and compose.

See you on February 9, 2024, for the release of ‘LE PASSAGE’.

Thank you for listening.

Klemen Breznikar

Thierry Zaboitzeff Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube

Art Zoyd | Interview | Gérard Hourbette