Phantom | Interview | Keyboardist Russ Klatt of Phantom’s Divine Comedy

There was a time when Detroit, Michigan’s Earl Theodore Pearson was one of the Motor City’s—if not the world’s—greatest rock ‘n’ roll mysteries.

Known alternately as Ted Pearson and, later, legally as Arthur Pendragon, his life was a real life Eddie and the Cruisers; a mystery akin to the “ghost group” marketing of the Masked Marauders, Lord Sitar, the Guess Who, the faux-Beatles known as Klaatu, and the ersatz-Elvis that is Orion, as well as Detroit’s earliest mystery-gimmicks in ? and the Mysterians and Sixto “Sugar Man” Rodriquez. Then there is the similar hype-marketing of Capitol’s Phantom in the grooves of Elektra Records’ forgotten glam-rocker Jobriath and “supergroup” jam-rockers Rhinoceros.

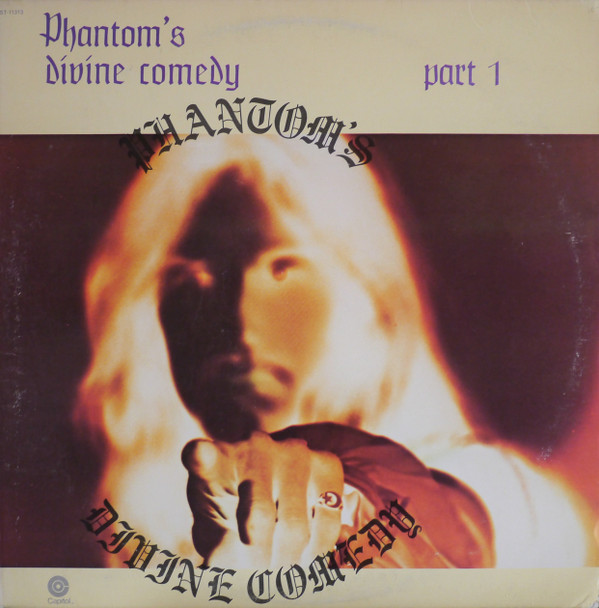

While the legend of the Phantom birthed in the pre-internet years of 1974, the myth of the musicians behind ‘The Divine Comedy’ that we know today is a byproduct of the post-1990s internet. When the Phantom’s analog endeavors saw a legitimate compact disc release—to commemorate Jim Morrison’s 50th birthday—in 1993 on Capitol Records’ reissues arm: CEMA Special Products, the tales of the wizard proliferated as the internet expanded its reach through its blogs and message boards, its media sharing, social networking and vanity websites. The music aficionados and connoisseurs behind those sites—mostly overseas European digital coffers—exhumed the tales of the wizard for a new century of music lovers of all things ’60 and ’70s proto-metal and progressive rock.

The tale of Jim Morrison’s doppelganger was a yarn that oft-embraced internet-based innuendos, themselves based in pre-digital record store and collector swap meet discussions throughout the ’70s and ’80s.

“Who is he?” we wondered at the time?

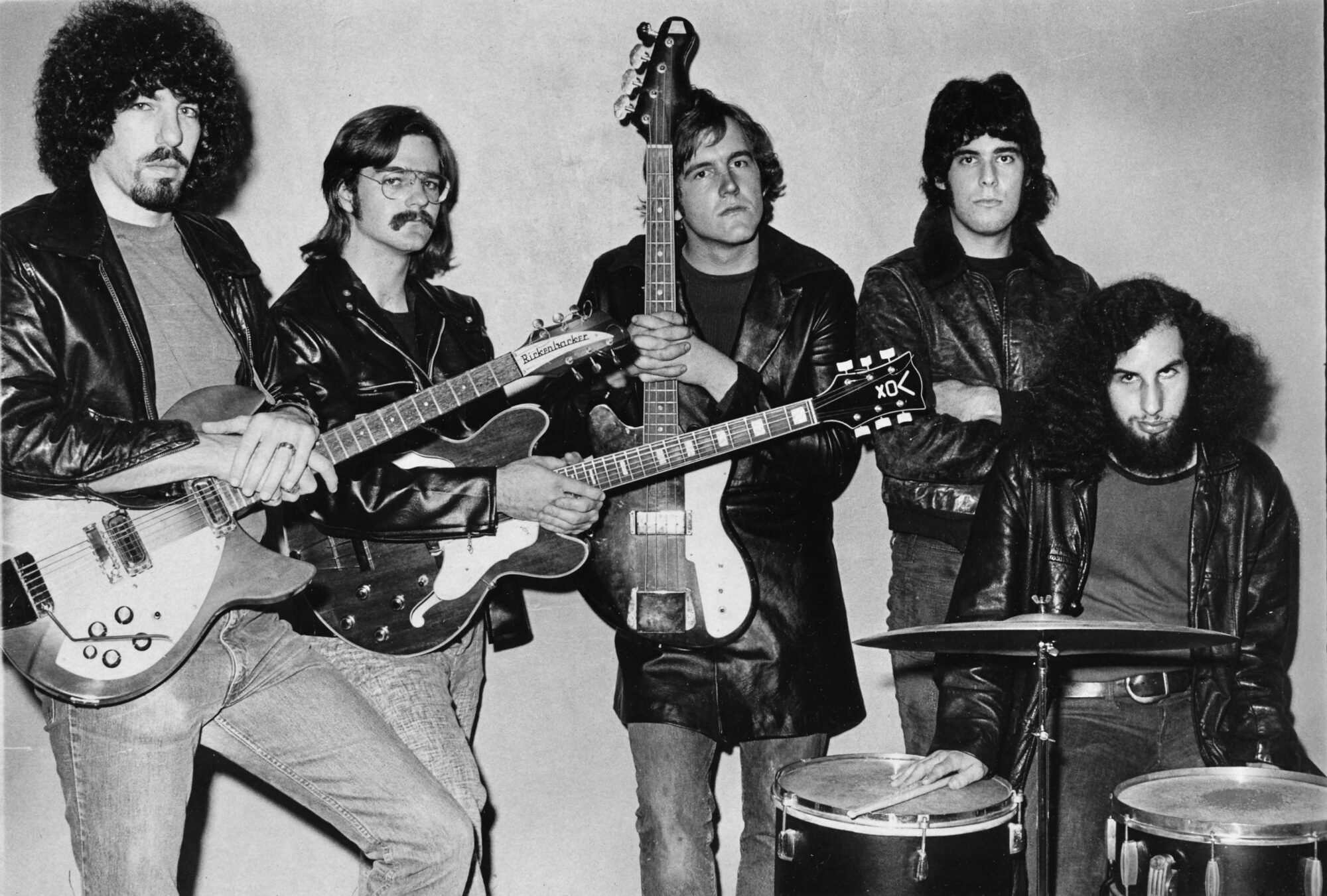

These days, we know that “The Phantom” wasn’t a scheme cooked up by Bob Seger. We know it wasn’t Iggy Pop with a band patched together with Detroit castaways by Alice Cooper’s manager, Shep Gordon. We know Ray Manzarek and Dick Wagner aren’t on it. We know it wasn’t a fourth, failed album by Detroit’s SRC—with a new lead singer. We know the band behind ‘Phantom’s Divine Comedy: Part 1’ was an obscure Detroit band known as Walpurgis. And we know the boiling musical mischief wasn’t as nefarious or mysterious as we once believed: the brew in the wizard’s cauldron was actually a pretty simple recipe of marketing hype.

Now it is time for an account on the career of Earl Theodore Pearson—based in the real, honest and unfiltered truth—from the recollections of Phantom’s keyboardist and Hammond B3 grinder of the Leslies, Russ Klatt.

“Phantom’s Divine Comedy: Part 1′ was an obscure Detroit band known as Walpurgis”

R.D Francis: So, after Phantom broke up, you transitioned into the art world?

Russ Klatt: I opened my gallery in October of 1974, which is when the whole Phantom project was breaking up. So I sold my Hammond B3 and the Leslies [a combined amp and speaker with a rotating “baffle chamber” usually paired with Hammonds] and took the money and opened a custom picture framing business; creating frames was something I had been doing part-time while in high school. So I opened up this little business and that, over the years, turned into three locations and then I scaled it all back to the one store in Birmingham. Then I expanded that store: I busted out a wall and put a gallery in and ended up in the gallery business for the next twenty years of my existence. Then I got out of that business in 2010. I had a lot of events at the gallery. The last show was in 1994 with WCSX [94.7 FM], our rock station here in Detroit, with Tom Weschler.

You were involved professionally with Tom Weschler during your years as a musician?

Yes, Tom and I go way back. Tom was our road manager for Phantom. He was Bob Seger’s road manager, as well; he actually quit Seger and came with us. [Another member of the Hideout management team that also worked with Bob Seger: Joe Aramini. He was the road manager for the Walpurgis precursor, Madrigal, as well as Tea; the latter featured Jerry Zubal, a future Ted Pearson associate in the band, Pendragon. This is, according to Jerry Zubal and Madrigal’s keyboardist, Paul Cervenek.]

Tom Weschler was primarily known as a visual artist. His first project as a photographer was Bob Seger’s ‘Mongrel’?

Yes. He also did Seger’s [March 1974 album] ‘Seven’.

Who else was part of Phantom’s management team?

Greg Miller was the assistant engineer at Pampa Recording [in Warren, Michigan]; he recorded the album. Gary Gawinek was there, engineering, as well. He was our manager, or something. What I had learned from Tom is that Gary took the tapes [Ted’s home demos] of Phantom [actually Walpurgis] to “sell it” to Punch; he couldn’t tell Punch it was Ted because Punch disliked Ted so much. I don’t know why or what happened that caused it.

For some reason, Ted totally disliked Bob Seger and always made fun of him. He felt Punch was spending too much time with Seger, saying, “Nobody knows who Seger is” and “He’s an old folk rock guy”. Ted called him “Pete Seeger” [a popular U.S. folk singer during the ’40s and ’50s] all the time. Ted just really had a problem with Seger. So I’d tell Ted, “Ted, nobody knows who in the hell you are! Let’s get out there and get some exposure”. Then he’d berate me on how cynical I was.

How was your relationship with Ted?

We were such an intense band; it was just incredible for four guys. But when we were doing the album, [Ted] was one hard ass son of a bitch to get along with. Then there was Mike Bailey.

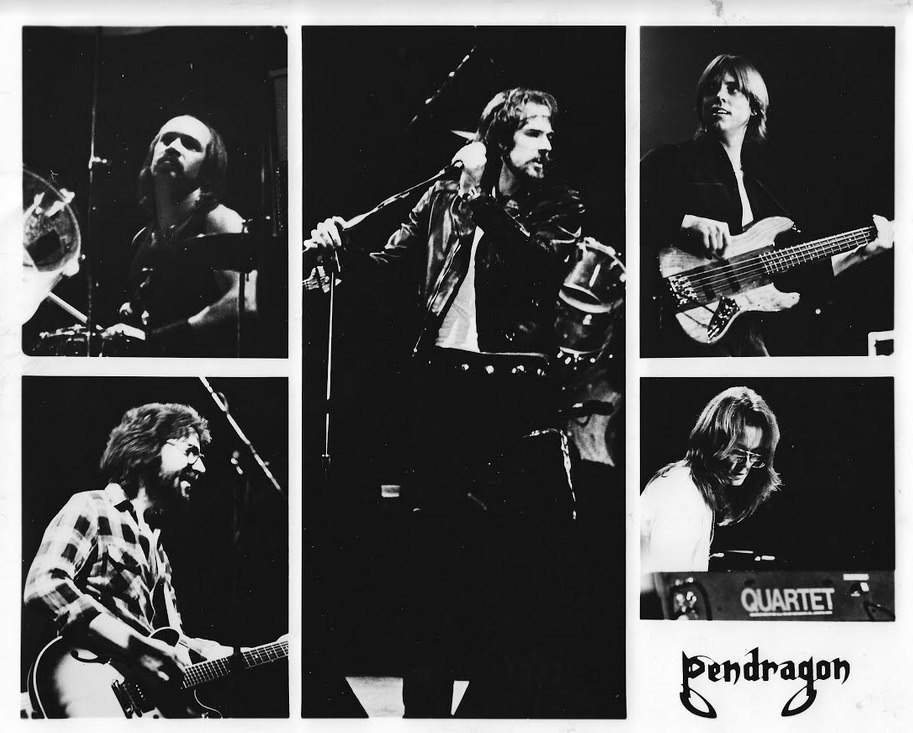

His name is associated with Ted’s next project, the late ’70s AOR-driven Pendragon.

Well, when Ted decided that Punch “wasn’t doing enough” for Phantom, he brought in Mike Bailey to be our manager. You can imagine how that went over with Punch. We come to find out that Mike was one of the bigger coke dealers in Oakland County. And Mike didn’t like me because I didn’t do coke. He’d put lines on album covers and pass it around during rehearsals and I’d say, “No, I’ve got a beer going here, I’m fine”. So we never hit it off. And that’s when everything changed: we went from Phantom, the band, to Ted being “The Phantom”—with us as “the backup band” to Ted. It was Mike Bailey who took Ted out to L.A., with Ray Manzarek and Robby Krieger, and that’s when it really, really changed. So that’s why Harold, Jimmy and I split, we go, “This is not how it used to be”. We saw the writing on the wall. The worst part was seeing Ted … it was terrible how bad those two got: they thought that they could do no wrong, that they were better than everybody else.

I tell you, the one single-most factor in the demise of Phantom was Mike Bailey. He ruined it. I think Tom Weschler and Gary Gawinek could have straightened Ted’s head out about Punch “spending too much time on Seger” and being so jealous of him. But when Mike Bailey came along and started throwing all the coke at Ted, he became invincible; you couldn’t even talk to Ted. Once Mike got in there, we only rehearsed a few times before Mike took Ted out to L.A. to the Whisky to hook up with Manzarek. Jimmy, Harold, and I said to Mike, “What are you trying to do to us? He’s not going to start singing Morrison songs with those guys. They’re not going to lower themselves to that”. Now, someone told me, and I can’t recall who, but I guess Ted did get up on stage with Manzarek and Krieger to do ‘Break on Through’ or something like that [the infamous “Jim Morrison Disappearance Third Anniversary Party” held on July 3, 1974] but the audience threw beer bottles at him. But I don’t know how true that is.

Here’s a perfect example of my experience with Ted. I had a Hammond B3 and two Leslie speakers. I had them up in the old house where we’d rehearse and record. This was when things were starting to not be so great; the feeling wasn’t like it when we were cookin’. Ted was playing through a Fender Twin and he blew his speakers; Ted was going to get it repaired, and so on. Well, we went to rehearse the next time—and my equipment sounded like shit. I couldn’t get any volume out of it, I couldn’t believe it. Wow, it was bad. Now, I kept my Leslies up: I took them to the guy that worked on Ted Nugent’s equipment; he worked on my amps and got more power out of them, and put these two, cool Electro-Voice speakers in. Boy, my two Leslie speakers could shatter your windows. Not long after that, the band broke up. I got all my equipment together and rented a U-Haul [trailer] and took it back to my parents’ house because, well, it was the only place I could store it. So, I started cleaning it all up because, as I mentioned earlier: I was going to sell it to open my frame shop. I opened the back of my Leslies and I discovered why my amps sounded like shit: Ted had taken my really expensive Electro-Voice SRO speakers and replaced them with his two blown speakers [from his Fender Twin].

You know, Ted has some nice equipment. He had his Fender Twin and a nice [Gibson] SG Standard. But it was intolerable, just intolerable. I just couldn’t believe somebody in a band could do that to a bandmate. So I took his two blown speakers back to the house one day, and [his future wife] let me in. Ted was out in L.A., or somewhere. Sure as hell: the back of the Twin is open, I look in the back, and I can see my two EVs in there. I took my two speakers out, tossed his blown, two speakers in the corner, and I left. So I got my speakers back. Jimmy and Harold couldn’t believe Ted did that, they go, “Wow, what a son of a bitch would do that”. But that, right there, told me everything I needed to know about Ted Pearson.

What bands were you in prior to working with Ted?

When I was really young, I was in a band, Downtown Clergy. We played all the sock hops at the Catholic Churches; that seemed to be who had all of the sock hops. We were together for six years as junior and high school kids, so it was pretty amazing we were together that long. Wilson Mower Pursuit’s drummer [Bob Franco]—who was ten years older than us—was a friend of our manager. [Bob] would come over and give us tips, telling us how to properly end a song, to “do this and do that”, just the nicest guy.

Did you know Paul Cervenek, who worked alongside your Phantom bandmates Harold Breedless and Jim Roland in the band’s precursors Madrigal and Walpurgis?

Paul and I have not seen each other since I was in 8th grade, back in the mid-‘60s. But Paul was a character and he was in some really good bands around Detroit that played the Grande [Ballroom] and stuff like that [Edges of a Broken Mirror and Good Tuesday].

Paul was the older brother of a kid I went to high school with. I had just gotten into this goofy little band in junior high. “You can be in the band, if you play keyboards”, they tell me. Well, I was a saxophone player; I don’t know how to play keyboards. But I went home and talked to my old man who was very supportive about music. So we got a little Farfisa Organ and an amp and he tells me, “take lessons”. Who in the hell is going to teach me ‘Light My Fire’ and stuff like that? So I talked to Cervenek’s little brother and he told me Paul can teach me all that. So he would come over and sit at the console organ my dad had in the living room and he’d teach me two or three songs that the band was going to work on that week. Low and behold, Paul got me to the point that I could play the keys, pretty good. Well, you know I was playing keys with Ted after Paul, so I stepped up to the plate. I always liked Paul. He was just a character and the nicest guy. But he taught me how to play ‘Light My Fire’ and ‘Good Lovin” and all those things back in the ’60s. So I got that gig in that stupid band, because of Paul.

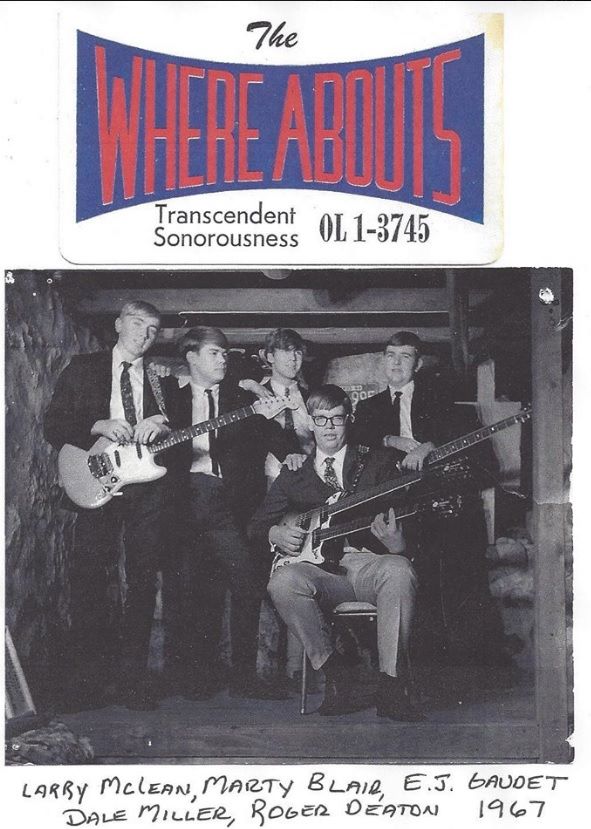

Now, I had the pleasure to play with a guy named Marty Blair. Marty was one of the best drummers I ever heard and self taught. He was the local Coca-Cola delivery guy, you know, the ones with the big trucks, and he was built like a wrestler because he slung cases of coke all the time. Now, Marty was a little out there; I think Agent Orange must have hit him, or something. Every once in a while, he’d get really strange, but he was the nicest fellow. I can’t recall how we hooked up; nonetheless, we played together for quite a while and he was, before I got in [Phantom]: a Hammond player. I said, “Marty, as good as a drummer you are, what do you mean you’re a Hammond player?”. He tells me, “Yeah, well, I didn’t like doing it, so I switched to drums”.

So Marty Blair is a missing Phantom member?

Yeah, Marty Blair, he lives in Clarkston, Michigan. So, we ended up playing together for a while. But he ended up having to drop out; we’d take a break from practicing and he’d fall asleep. The guy is just busting his ass working all day and he decided he just couldn’t do it anymore. So he started playing drums at one of those non-denominational churches that had the “big band” and everything; he did that because he could play in the morning, instead of the night.

Is there truth to the rumor that Phantom was to appear on U.S television on NBC-TV’s The Midnight Special?

Now, I heard, and I don’t know how right this is: When Ted started with the nonsense and brought Mike Bailey into the band, Punch sued Ted for breach of contract. None of the guys in the band, me, Harold and Jimmy, were ever contractually signed to the band.

I got in, and the first thing the band did, well, we learned all the tunes, but the song I played Hammond on [‘Tales from a Wizard’]: we just went right into the studio [Pampa] and cut that right way, to finish the album. I also cut the background vocals on ‘Black Magic/White Magic’, that’s it. There was such a panic to do everything, as Punch wanted to get us out on the road.

I was told we were booked, in March 1974, on The Midnight Special and that was going to be the band’s debut [the ‘Calm Before the Storm’ b/w ‘Black Magic/White Magic’ single would be performed]. But everything just got so crazy with Punch suing Ted, Ted was suing Punch, and Punch got some sort of injunction where Ted couldn’t play out, professionally, for the next five years [so until 1979]. Now, again, this didn’t affect Jimmy, Harold or I because we weren’t contractually signed to the band.

And the band was to serve as Bob Seger’s opening act?

The way it was going to work, as Ted explained it to the band: We were going on the road for 48-weeks to open for Bob. When we weren’t opening for Seger, we were opening for Bachman-Turner Overdrive. So, Ted charts it out on a map, one day: “We’re starting up here, in Winnipeg … we’re going to come down this coast, and up here … and we’re going to play in Florida, and then we’ll end up in L.A.”, and so on.

I think one of Ted’s issues was opening for Bob. Ted thought he was a “bigger deal” than Bob [again, because of Punch’s promotional initiative for the Phantom project]. We say to Ted: “Ted, nobody knows you!”. Bob was big in isolated areas. He did well in L.A., he did well in Denver, southern California he was big in, but he wasn’t a “clean sweep” like he is now, all over the world.

I only met Bob a few times, in the studio, as I used to hang around Pampa all the time. The only thing I could say about Bob is that he never seemed really sharp. He could write songs like you couldn’t believe, obviously. He’s a great rock ‘n’ roll singer. But when it came to the business stuff, he should thank Punch Andrews, everyday, for holding his hand through everything because I don’t think Bob could have pulled it off without Punch. Punch was his mentor, his savior, his guiding light.

How did you become involved with Phantom?

Well, I had the opportunity, and never took it, to audition and play keys for Seger, thirty some years ago, before Phantom. I knew Punch; I’d stick my head in the door of his shitty little office in downtown Birmingham, which he’s still got, just an old, little house. But I’d stick my head in and ask Punch if anyone was looking for a Hammond player, so my name was in front of him a little bit. Anyway, I heard that Seger was looking for a keyboard player. So I talked to Jim Bruzzese, you know, the owner of Pampa Studios, who recorded all of Bob’s early albums. I tell him excitedly, “Jim, I got this chance to audition for Bob”. Jim tells me “don’t take it, don’t even think about it”. I told him, “Are you crazy? It’s the best opportunity I’ve ever had”. Jim tells me, “You’ll practice six days a week. Seger’s going to pay you $150 a week — and that’s it”.

Seger hadn’t been able to really have a nationwide hit and Jim just started, really downing Bob. There was a lot of that going on during the early parts of Seger; he just couldn’t break out, nationally. I just wanted to do the audition, so I could say, “Yeah, I’ve auditioned for Bob”. I never did it. Later on, I found out that Punch paid the band a salary every week—and he invested their money for them. I think that was the best thing a manager, especially back in the day when everyone was getting screwed, could do. I thought it was the coolest thing anybody could do.

Punch Andrews also got into club management.

Right. He owned a couple of clubs around town and made sure he’d feature all the good guys around here, like Bob, and Third Power and Ted Nugent and everybody around town. Punch was a good guy and he knew that these musicians could screw up so fast, so he started investments for them. I had so much respect in the world for Punch because of that, his looking out for musicians. Instead of these other guys ripping everybody off, Punch was trying to substantiate their personal wealth. That’s so commendable to me.

Phantom, when the band was known as Walpurgis—and with different members backing Ted—did a show at the Grande Ballroom on October 30, 1971, a Halloween Eve show, opening for Joe Cocker with Frost as the undercard. Through that show, they came to meet Billy Davis, formerly of Detroit’s Hank Ballard and the Moonlighters, who was working A&R for Astral Studios in New York. It is said Walpurgis recorded an album there. Is there any truth to that: that there’s an unfinished or unreleased album, prior to ‘The Divine Comedy’?

No. This is the first I am hearing this. There’s no other album to my knowledge. The only album I heard of is ‘The Lost Album’ [the demo tapes of Ted’s next band, Pendragon, recorded in 1978 at Detroit’s Fiddlers Music—later marketed by the pirating industry as by “Phantom”].

So what you worked on with Phantom, those were all-new recordings, not a retooling of, or trying to fix or salvage those Astral sessions?

No, not at all: it was all new recordings. Everything on ‘The Divine Comedy’ was recorded at Pampa Recording Studios: all of it. Somewhere, I’ve got photo slides of Ted sitting in the studio doing the “Merlin” poem, to set up that song. So, yeah, everything was done at Pampa for the album. It’s all just too bad, you know. That album could have been so good and so powerful. These people that I’ve talked with over the years that said to me, “Man, we just love this music and what was it like …”. Here I am talking to these guys, these fans, some forty years later and I tell them, “It was a good, good band”. No question about it.

Even more so as a four piece, which you previously mentioned.

Yes. Jimmy’s a solid drummer. I think a better bass player would have driven it better. All of the piano work was done by Ted, by the way. I only played on the last track of the sessions to lay down the Hammond, which was ‘Tales from a Wizard’, that’s the only song that has Hammond on it. As far as I know, the second bassist on the album is Ted. The Wells brothers [Howard and Russ] that you mentioned weren’t there when I was involved.

So you were not a member of Walpurgis? You didn’t join the band until they hit the studio and the album was almost completed and its promotion—with the L.A. radio-leaked single, already released in late 1973. At that point, Punch changed the name to Phantom, as a quick way to market the group. You came in on the tail end of all that to lay down some Hammond B3, become part of the touring band, and that’s how you started.

You got it right on the head. That’s exactly how it happened. I was 19 years old and my head was spinning, it all happened so fast. Here’s a story: I got the gig without playing a note. How does that happen? Well, I was called up to the house in Rochester that we practiced at [on South Boulevard, east of Rochester Road]. I met with Gary Gawinek and Ted. They quizzed me on all sorts of stuff. The biggest thing was: “Are you going to college?”. I told them, “I just went my first semester and college and me, we don’t get along”. The next thing was: “Do you have a girlfriend?”. “No”, I told them. “Okay, you’ll do”, they tell me. “Wait, guys, don’t you want to hear me play?”. They say, “We’ll show you what we want you to play”. It was the easiest gig I ever got! I guess because my name got around Punch’s offices.

Sadly, we lost Arthur Pendragon to suicide in March 1999. Do you know if Jim Roland is still alive?

As far as I know, he is, and still is, in Michigan. Remember that drummer that was a keyboardist I mentioned: Marty Blair, one time with Phantom? He stood up with Jimmy at his wedding. But I don’t know if Jimmy died recently, or anything. You know, Jimmy Roland was a store manager of a K-Mart store [the chain is gone now; it was a major U.S. retail chain from the ’60s into the ’90s]. Jim quit K-Mart because Ted convinced him we were going on the road. He quit that job: a secure store manager’s gig. I still think the whole thing is just a big shame because of what could have been.

You know, here’s a good example: I played a golf outing and took my son to play in it with me; this is going way back. My son was all excited because Bob Seger and the Silver Bullet Band were supposed to be playing at this golf outing, too. So, we’re getting our clubs out of the trunk and putting our shoes on and there’s Punch, a few cars down, putting his shoes on. I say to my son, John, “Come on, you’re going to meet one of the most important guys in the music business”. So I took him down and we greeted and started talking about our golf game and I said, “I want my son to meet the legendary Punch Andrews”. And Punch was kind and very cordial to my son. So, Punch goes [with his hands], “Do you know your dad came this far from being a rock star?”. And I thought, “You know, Punch, you’re probably right. This thing could have been out of control”. If we could have done that Midnight Special gig, I think that just would have blown people away for the type of music we were doing, the intensity of it all. I think it could have been great. It really is too bad.

R.D Francis

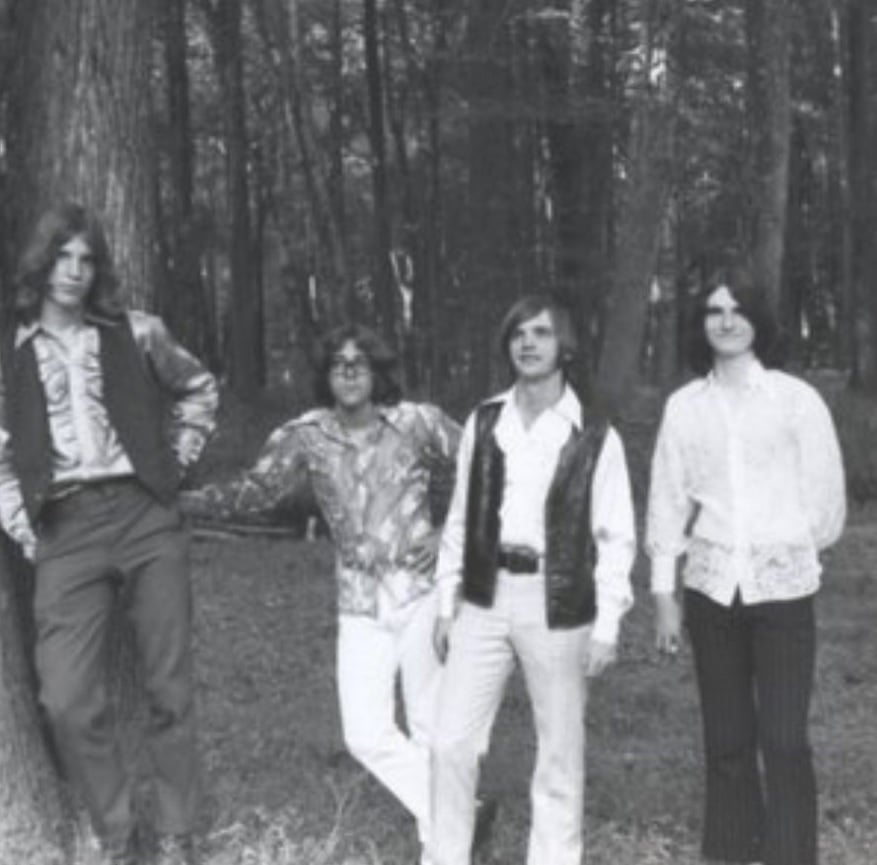

Headline photo: Walpurgis promotional photo taken by Tom Weschler at the gates of Detroit’s Cranbrook Manor in 1973 | Left to Right: Ray Campbell (guitars and keyboards), Harold Beardsley (bass), Jim Roland (drums), and Ted Pearson.

Tom Weschler Facebook

I’ve had the Phantom for decades, of course.

So it wasn’t a new discovery for me, anyway thank you very much for the interesting interview.

Yes. But you didn’t know the true, real story. All you knew was rumors, most of which was 100 percent wrong. This writer did his research, found old members and got the story straight — and you pay back the hard work with insult. I applaud the writer’s efforts and he gets my respect. I love knowing what really went no with the Phantom’s album.

I knew of the album, but never knew the story behind it, beyond people thought it was Jim Morrison. What a crazy tale! It’s the first I heard of it. That’s wild you found a surviving member. Great investigation!

I was ale to see my cousin Ted play one time and the band was great but the bikers didnt like them

Ted Pearson is my first cousin. He grew up in Oxford Michigan. His Mom and my Dad were siblings.

Great atmospheric record. Sad what might-have-been story.