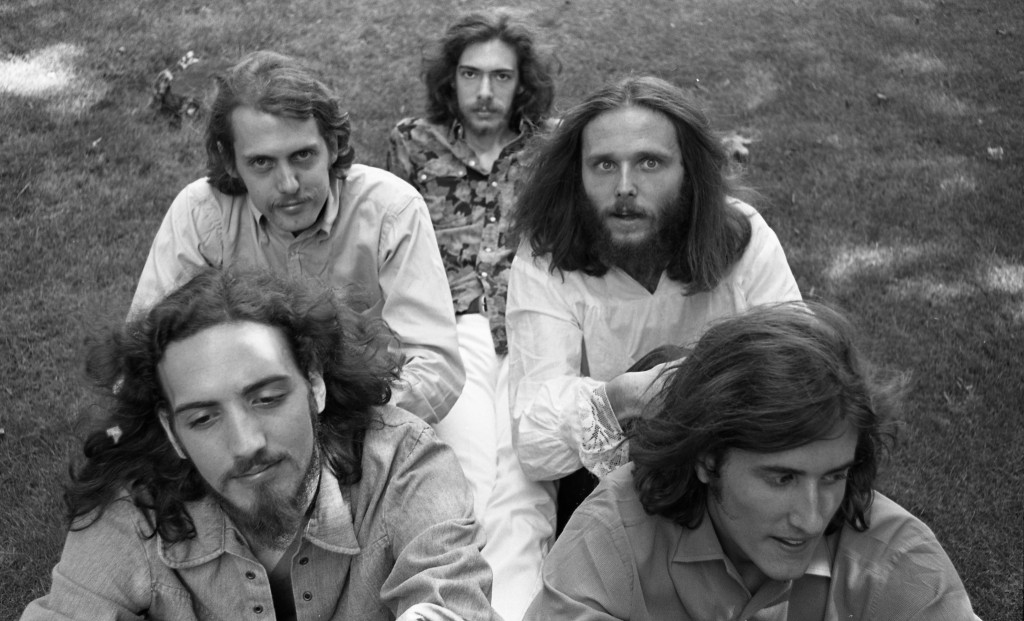

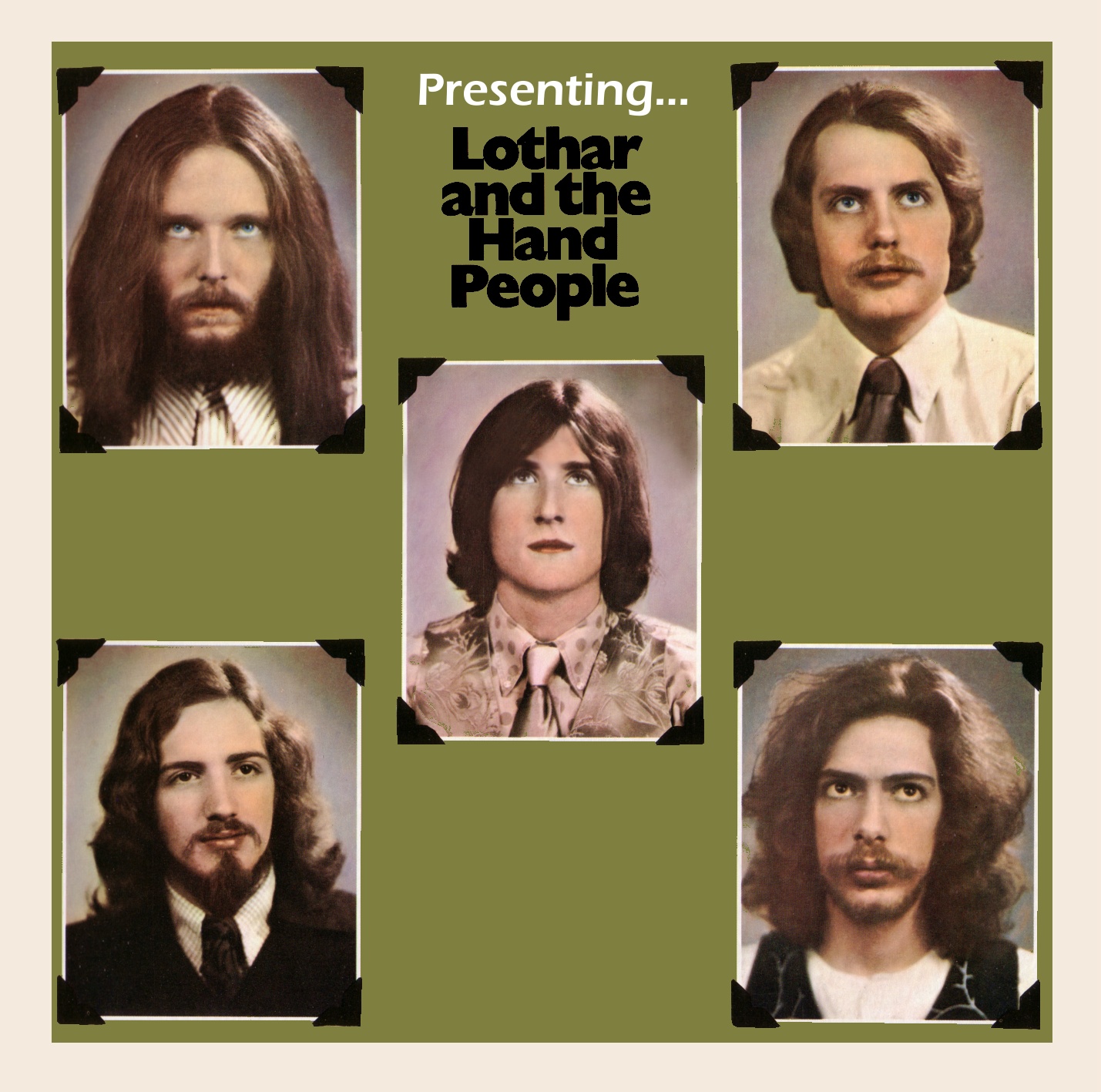

Lothar and the Hand People interview

Lothar and the Hand People was active in the West Village music scene. The band recorded two albums for Capitol Records and toured widely. Lothar and the Hand People was the first band to play live performances on a Moog synthesizer with Kim King and his bandmate Paul Conly as programmers of the first portable analog synthesizer to come out the laboratory.

Later in this year Sundazed Music / Modern Harmonic will be releasing a fantastic live recording of the iconic theremin lead Lothar And The Hand People! Below you can already enjoy a fiery live take on one of Lothar And The Hand People’s most beloved tunes, from their very last show at Amherst College in 1969!

Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life? Did the local music scene influence you or inspire you to play music?

Rusty Ford: I grew up in Connecticut, approximately an hour from New York City. My parents were into Broadway show tunes, satirist-singer-songwriter-pianist and Harvard professor Tom Lehrer and calypso music of the Bahamas where my Dad’s former college room-mate and business partner lived. In the late 50’s/early 60’s there was no local music scene in Connecticut. Starting at approximately 8 years old, it was me and my cousin listening to 45’s for hours, every time we got together.

John Emelin: I grew up in Mamaroneck NY, 20 miles from NYC. Loved all kinds of music from very early on. The Regency TR 1 transistor radio came out when I was ten, and I would listen to Alan Freed with the radio under my pillow. Little Richard and many others opened up worlds to me that I couldn’t have imagined. Mainly the idea that there was a life of Big Fun awaiting me, something the schools weren’t teaching. There was a wonderful record store in Mamaroneck, and the guy who owned it would point me towards things I might not have come across myself: Olatunji, Ornette Coleman, etc. Changed my life.

Paul Conly: Grew up in Colorado and Wyoming. Music was a big part of my family life. My mother was a professional musician and music teacher. My dad loved to sing and they wrote songs together in the 1940’s. The family influences included two of my uncles, both named Bill. One Bill was a DJ and radio personality in Denver. He taught me how to record audio. The other Bill had been a musician in his youth and continued to play piano at home for all his life. He taught me some music theory and also gave me some piano lessons. He sold his bass viol to my parents so that I could have my own instrument when I joined the junior high school orchestra. My mom, dad and the musical Bill were more influential on me than any local scene.

What was your first instrument? Who were your major influences?

Rusty Ford: My earliest influences were Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Fats Domino, Huey “Piano” Smith, Jerry Lee Lewis and The Everly Brothers. Bass wasn’t on my radar until my sophomore year in high school. My first bass was a used Danelectro Longhorn 4-string bass for which I paid $90, including the case. I wish I still had it.

John Emelin: Played ukelele (and its cousin, the Tiple) and guitar, and autoharp. Folk was all the rage, and a friend and I formed The Muscatel Marauders, a folk/comedy act, which performed mostly at school. We also added a third friend and did some improv, which was just being born. Saw Bob Dylan at a hootenanny at Town Hall, for a dollar. Such power. Of course the Beatles changed everything. As a freshman at DU, a friend and I drove to Chicago and saw the Stones at the old Arie Crown theater. We were blown away. Went back to Denver and started Lothar. Many influences: Jimmy Reed, John Hammond, Jim Kweskin, Paul Butterfield, Lieber and Stoller, Chuck Berry etc.

Paul Conly: When very little I sang and started on the piano. When I was 7, I switched to the ukulele because I was too small for a guitar. In 2nd grade I took up the bass viol in my school’s string orchestra and took lessons on guitar. My bass and piano studies were in Western European classical music. My father loved mainstream jazz and I was influenced by all the master jazz musicians.

What can you tell us about your life prior forming the band?

Rusty Ford and Kim King: Tom, Paul, and Rusty were all in bands in high school. Kim came to Lothar through the folk scene.

“We were the very first band to perform live with a Moog synthesizer.”

You were one of the very first bands to experiment with Moog, Ampex tape decks and Theremin.

Rusty Ford and Kim King: We were the very first band to perform live with a Moog synthesizer. We had a pre-existing relationship with Bob Moog because we’d been performing with a Moog theremin (which we named Lothar) since our earliest gigs in the Fall of 1965. We met our original lead guitarist, WC Wright, at the Denver Folklore Center in October ’65. WC bought in Kim King — also through our friendship with the Folklore Center.

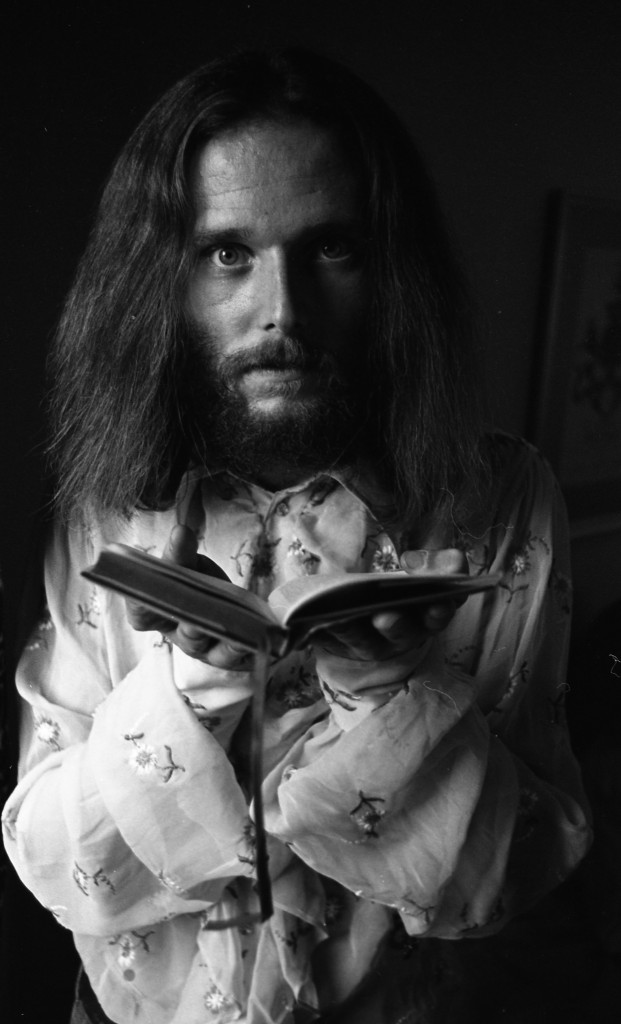

John Emelin: I was fascinated with strange sounds as a kid, and never got over it. I had heard the theremin in movie soundtracks like Spellbound and electronic sounds in Forbidden Planet. I think it was during college that I ordered one from Bob Moog, so I had it when the band was formed. Paul Conly will have more detail about how our journey with the Moog began. Remember, the longest journey starts with a single oscillator…

Paul Conly: Through my uncle Bill’s experience in radio broadcasting, I learned the basics of recording and tape manipulation, earning an FCC license. My first awareness of the theremin was probably from seeing a Jerry Lewis movie, “The Delicate Delinquent” (1957). In the film Jerry has a neighbor who is an eccentric scientist. This man has a theremin and he lets Jerry play around with it. A year earlier, 1956, I had seen the film, “Forbidden Planet” which had an all electronic music score. This film had a great impact on me, giving me the realization that music could be made with pure electronics.

Where from did you know each other?

Rusty Ford and Kim King: We met our original lead guitarist, WC Wright, at the Denver Folklore Center in October ’65. WC bought in Kim King — also through our friendship with the Folklore Center. In the spring of 1966, WC decided to change direction and study tabla with Ali Akbar Khan in California. Enter Paul Conly.

Can you elaborate the formation of Lothar and the Hand People?

Paul Conly: John Emelin was in a fraternity at the University of Denver. He was also a folk musician. He and a frat brother attended a Rolling Stones concert right before they returned to school in the Fall of 1965. En route back to Denver they decided to form their own rock band, forsaking folk music for R&B. Back at DU they recruited Tom Flye and Rusty Ford on drums and bass, respectively. From the Denver Folkore Center they encountered Kim King. The original guitarists, Richard Willis and W.C. Wright, were soon replaced by Paul Conly, rhythm, and Kim King, on lead.

John Emelin: My friend and roommate Richard Willis and I played some. He knew the New Lost City Ramblers stuff, and other old-timey folk things. Went to Chicago to see the Stones, and immediately came back to Denver and started looking for band members. You better ask Rusty what he remembers. All a blur to me..

Were you in any other bands before?

Rusty Ford and Kim King: We were just out of high school when we formed L&HP. As noted earlier, 3 of us played in high school bands of no great significance — except to us and a few classmates.

John Emelin: A Jug band in Denver…

Paul Conly: I played in local jazz ensembles in Denver and Boulder. None recorded professionally.

“Lothar , the theremin.”

What was the scene in Denver?

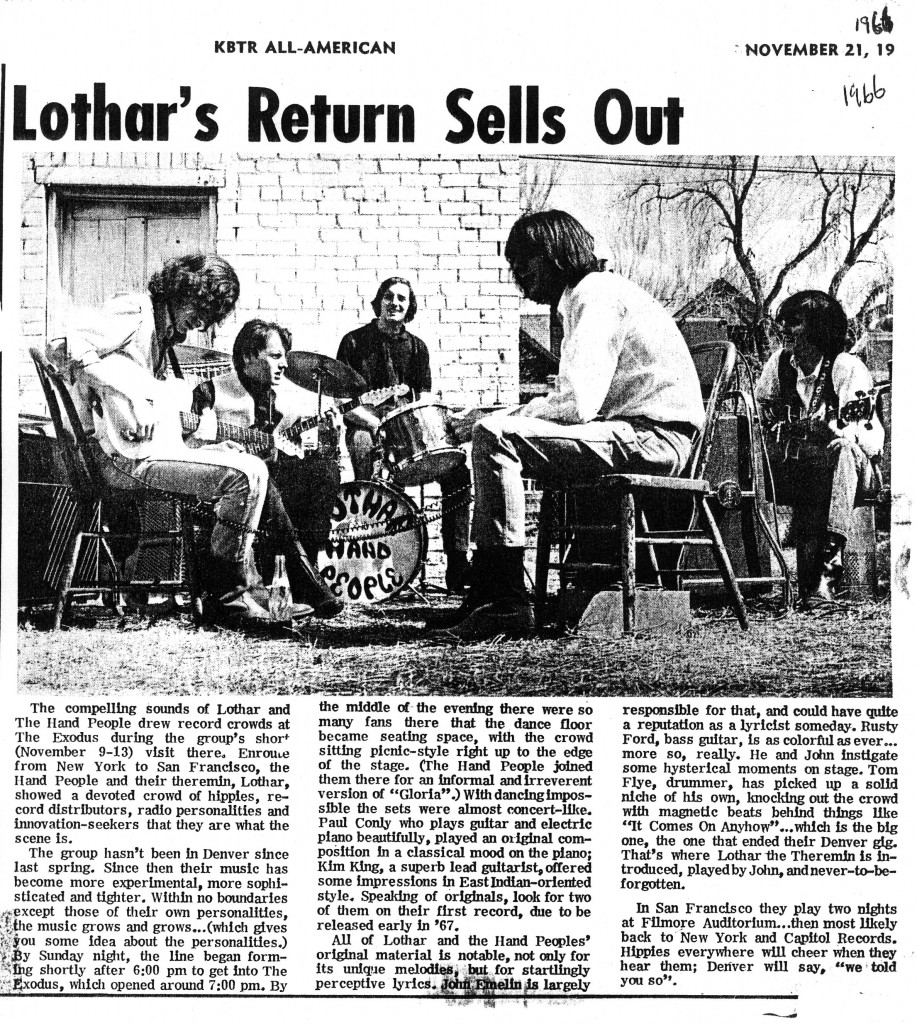

Rusty Ford and Kim King: Wide open. Back in 1965/early 66, most of the bands in Denver were cover bands. For the first few months we were basically a blues band. But we were listening to many different kinds of music, including, in no particular order, composers like Edgar Varése, Charles Ives, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luciano Berio, Steve Reich, John Cage, Hamza El Din, Ali Akbar Khan, Ravi Shankar…I know I’m forgetting other important names … And of course we were listening to Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Mississippi John Hurt, JB Lenoir, the Beatles, Stones, Kinks, Woody Guthrie, Jim Kweskin Jug Band and so many others… We were all over the place with our record collections. And we had a theremin right from the start of the band — though, at the time, we didn’t know how best to fit it in to the blues material which we were playing in those very early months. Those influences had no choice but to creep into the material which we wrote. Our first gig of any consequence was a 2 -week booking in Aspen, Colorado. The bartender kept requesting songs like “Louie Louie” and “Gloria”. We had already started incorporating original material into our set. Playing “Louie Louie” and “Gloria” ad infinitum to please the bartender was getting old, so rather than letting Kim and WC play extended guitar solos, we’d break into an improvised freak-out bridge — adding Lothar , the theremin.

“In 1965, we were some of the only young men in Denver with long hair, which brought much hostility our way.”

John Emelin: There were established local bands. The Moonrakers, the Galaxies and many more. Lots of clubs for the 18-21 crowd. The Denver Folklore Center gave rise to a more contemporary sound after the Beatles. In 1965, we were some of the only young men in Denver with long hair, which brought much hostility our way.

Paul Conly: Denver had a stable jazz scene from the days of Neal Cassidy and Jack Kerouac. Many national names stopped off in Denver to play while traveling from one coast to the other. There was not much of a blues scene here, apart from in the Five Points section, which really featured more jazz players. There was always a country music scene The younger white audience was well into the folk music scene of the 50’s. When the Beatles broke out on national radio, it started a big change in the types of bands formed here. Before, there was a surf music following, and even a local band, The Astronauts, who did well with the surf music you would hear out of California. All of these genres were very imitative of the music out of either Nashville, Los Angeles or New York City.

Soon you decided to move to New York City, where you got signed to major label (Capitol). How did they got in touch with you?

Rusty Ford and Kim King: Most of the clubs back then were located in Greenwich Village. To name a few: The Gaslight where Dylan “started”; The Playhouse, home to the Fugs; the Cafe a GoGo, home to the Blues Project; the Cafe Wha (Jimmy James aka Jimi Hendrix); The Night Owl, home to The Flying Machine (James Taylor/Danny Kortchmar), The Lovin’ Spoonful and many other groups; and The Bitter End — though it was mostly a folk club. Because these clubs were all within easy walking distance of one another, record company execs could troll the neighborhood, looking for new artists. We were initially courted by Columbia Records. We did a demo session for them but we passed on them. The demo sounded like a studio band — and we were never a studio band. In the end Capitol found us at The Night Owl Café.

John Emelin: At the time, the big record companies had east and west coast offices. In 66, even the big labels on the east coast were lacking longhair acts. Scouts came to the clubs looking for us.

Paul Conly: We were hired at a club in Greenwich Village that was one of the “showcase” for bands seeking the attention of agents, managers and record companies. We did well there, attracting a lot of attention and earning publicity in the NY papers and the Village Voice. The President of Capitol Records came in person to audition us in the Village. His approval secured us the recording contract with Capitol.

You released three 7″ before your debut.

Rusty Ford: They were recorded at Capitol Records studio in New York. Dick Weissman was the producer. My personal favorites from those sessions are “Comic Strip” and the original, very raw version of “Today Is Only Yesterday’s Tomorrow.”

John Emelin: Remember the singles, but not much interesting about them. Paul likely has stories…

Paul Conly: These were produced by Dick Weissman, our first producer at Capitol, which had its own studio in New York. As it turned out, we were disappointed with the engineering out of that studio and the producer’s hesitation about our experimentation. For example, the engineer was adamant that we would not use a fuzz foot pedal on Kim’s guitar because it distorted the sound. Mr. Weissman did the best job he could under the circumstances. He is a great musician in his own right, but didn’t feel that our experimentation would be commercially successful. Well, he was right about that.

“Once we locked Bob out of his studio so we could record ourselves out of his supervision.”

Capitol Records offered you to record your debut. Robert Margouleff was your producer. What are some of the strongest memories from recording it?

Rusty Ford: Robert Margouleff owned his studio, so the clock was never running. We had the luxury of time if not equipment. He only had a 4-track. But from my point of view, it was a valuable training ground.

John Emelin: Learning how to use the Moog.

Paul Conly: Bob is a brilliant man and had a classical music background. We were brought to him by Walter Sear, our first sponsor from the Moog Synthesizer company. Bob was producing a feature film in his studio and it was momentous for me to see what went on in the editing suite and behind the camera. We were young and a bit pretentious. Once we locked Bob out of his studio so we could record ourselves out of his supervision. However, through our arrangement with him and Walter Sear. Bob was able to go forward as a record producer and even as a synth guy, working with Devo and Stevie Wonder and others, quite successfully.

How did the idea to use theremin came along?

Paul Conly: John Emelin had bought the theremin from Dr Robert Moog in 1965, or perhaps earlier. When we were playing in Denver in clubs, we were asked to play the hits of the day, such as, “Gloria” and “Louie, Louie.” We would stretch these danceable songs out for length by having long instrumental sections featuring the lead guitar. I asked John to add the theremin to a “Louie, Louie” break one night. It was such a shock and mesmerizing experience for the crowd that we knew we had to add theremin to our show every night. Soon, it seemed obvious to name the theremin Lothar, because the name of the band was Lothar and the Hand People, and yet, nobody among us humans were named Lothar. So the Moog theremin was the best one to get the name of Lothar.

“Experimental electro-rock.”

How would you describe your sound?

Rusty Ford: I’m very excited about the restoration of the live recordings because, in my opinion, it captures what the studio recordings failed to capture: that we were a really good garage band. And as our music evolved — again in my opinion — we were a better band live than we were on record. At least, that’s what I hear in the best moments of the restored live recording of our last gig in December 1969.

John Emelin: I’ll let you do that…

Paul Conly: Experimental electro-rock.

“The experiments were the most important aspects of our studio work.”

You got some positive media responses after the LP was out and “Space Hymn” received quite a lot of FM play.

Rusty Ford: We did get good reaction from both media and our audiences, but we never broke the sound barrier of the next level.

Paul Conly: Space Hymn sold somewhat better than Presenting…Lothar and the Hand People. The song and composition of the track, “Space Hymn”, was played at first on radio stations although some of them were told that people were being hypnotized by it while driving. There were some good reviews from contemporary critics, like Lenny Kaye for Rolling Stone, but overall my feeling was that very few people really understood what we were trying to do. We were barely within the bounds of pop music and not really believers in becoming recording stars. The experiments were the most important aspects of our studio work. Our concert reviews were not always good during the last months. Some critics thought that we were too weak as songwriters to make a decent album. My own thought was, “Gee, I am so sorry that I didn’t write “Hang On Sloopy!”

Was there any concept to your albums?

Rusty Ford: Not that I recall.

John Emelin: Not that I remember.

Paul Conly: I am afraid not. Each song was to carve out its own swath. My over-riding ideal was to demonstrate that the world of music could benefit from the colors and dynamics of electronic sounds. That emotions could be expressed through any machine. My actual instrument was the loudspeaker. It mattered not that much how the signals were originated, whether from vibrating strings over wood, or pulsing voltages generated by digital manipulation.

Space Hymn was different than your debut. What’s the story behind it?

Rusty Ford: Certainly, we had evolved and that was reflected in the choice of material, and the difference in sound was due to the big difference in studios, Record Plant compared to Centaur, and producers, Venet compared to Margouleff.

Paul Conly: Obviously, an ode to the astronauts as first humans on the moon. Exploring the profundities of this amazing event. Also, confounding the journey into outer space with the journeys made into the inner space of the human mind and spirit. We considered the mixture of “organic” musical instruments with electronic instruments as representative of the dual journeys.

Like the first LP, it was a selection of individual songs which covered a range of musical styles. The LP pointed to the future, what was to come after 1969. Musically, many were wanting to return to the organic, folk forms, which meant the creation of Country Rock. Others were nostalgic for the doo-wop days and street corner singers. Lothar wanted to become more than a Theremin. Ultimately, Lothar was to be a semi-autonomous robotic musician capable of creating wave forms, spring-activated percussion beats, and mapping a stage so that Lothar could travel to the human musicians and interact with them. In 1971 I figured that in 50 years we could communicate in both directions with Lothar, and in English. My reckoning was a not too far off. It’s been nearly 50 years now and Alexa and Siri and I speak regularly. But Alexa is not Lothar. Lothar by now could converse, but would be an inspiring and provocative improviser of music as well as a fellow jammer.

You shared stages with many bands.

Paul Conly: Perhaps there are too many stories. And the honor of meeting with many talented players. Among my favorites was Jimi Hendrix with his beautiful soul and his humility, despite his awesome talent. In New York, I was delighted to discover the Fugs playing at another bar around the corner. They were reciting poems and lyrics that spoke of that present moment, that would rock people’s attitudes with a raucous sense of humor and a desire to make the world a better place. Their musical core was the Holy Modal Rounders with whom I spent many happy musical hours. I also felt honored to spend some time with Buddy Guy and Junior Wells, kind gentlemen who were the epitome of bluesmen.

Almost every musician I met was willing to encourage me in my work and was interested in the results of the audio experiments. Having a drink with Keith Richards was an exciting time. Allowing others to play the theremin was always enjoyable. It’s really fun to try it. Notable players of Lothar were comedian Richard Pryor, actor Orson Bean and Captain Beefheart.

What happened next?

Paul Conly: By the Fall of 1969, we were coming to a crossroads. Record sales had tapered off and college bookings were getting sparse. One road led to cajoling a third album from Capitol. Another direction lay the career path to engineering and producing records. Yet a third trail was heading back to Colorado to ‘get back to the land’ for a simpler lifestyle with a wife and children. My own road away from the band was in the direction of becoming a composer of music for theater, film and dance. John stayed with him family and took them out west where he built a log house in the mountains. Kim went to work for Jimi Hendrix as 2nd Engineer and protoge of Eddie Kramer. Tom Flye signed up with Record Plant and went from an apprentice engineering position to becoming a full chief engineer. He soon was mixing the Woodstock Album, and his first gold record was for Don McLean with “American Pie.” Rusty Ford and I had a new version of the Hand People, with Rusty on bass, myself on guitar and the new ARP Modular Synthesizer, and the playwright, Sam Shepard, on drums . We were part of the show of his off-Broadway premieres of two one-act plays. By early 1971 I was able to play some results of my computer-music work realized with a colleague, Allen Razdow. There were presentations in Cambridge, Boston, at Carnegie Hall, and at the watershed “Software” show held at the Jewish Museum in New York City.

Are you excited about the latest Sundazed release?

John Emelin: Very excited. I have not heard a lot of these specific tracks in 50 years!

Paul Conly: We are all excited about the Sundazed release. These tapes were neglected for more than 50 years and have been resurrected by Bob Irwin at Sundazed. They show the original energy of the group playing in front of college-aged teens. The members shared a love of Delta Blues, folk dances and rhythm and blues master songwriters. Right in line with the bands of the British Invasion that flooded American popular music. The band quickly gathered an official fan club and filled up clubs in Colorado consistently.

The charisma of the band and the driving music soon led to recording offers and the group decided to travel to New York City to explore recording contract offers. This dream did come true, and in a remarkably short time period because the new original material played in New York plus the wild psychedelic improvisations with electric instruments was radically different from what other groups were doing.

What currently occupies your life?

Rusty Ford: In 1980 I transitioned from music and music production to film production. I worked in TV advertising production until retiring in December 2019. Throughout those years and right up to the present day, when not traveling with my wife, I continue to play bass for various charity events. And in the growing season, I supply my friends and neighbors with veggies from my organic garden.

John Emelin: Retired, living in Southern Mexico. Interested in scuba diving, archaeology, birds, and of course, music.

Paul Conly: I am still composing music using multiple instruments. More than 200 films and tv projects have my scores and these films and videos have won numerous awards, including Emmys, Student Oscars and the DuPont Award. Now I have my own project studio with lots of computers and three different operating systems. My new dream is that perhaps Sundazed will agree to release some of my music on their label.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

John Emelin: Thank you! Thanks so much for your interest!

– Klemen Breznikar

Lothar and the Hand People Official Website

In Memoriam: Kim King

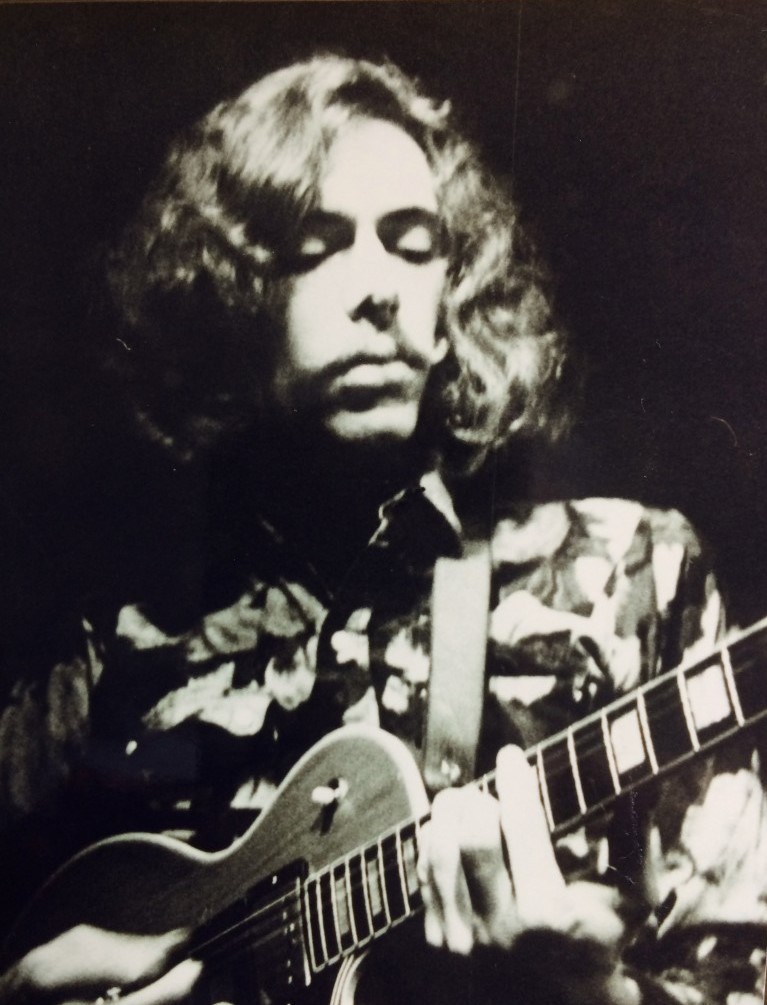

Kim King, whose musical life included being lead guitarist and synthesizer player for Lothar and the Hand People, died following a long illness in San Rafael, California on August 30, 2016. He was surrounded by family and loved ones.

In the early 1990s, a dusty old record store loomed like a dark beacon on West University Avenue in Champaign, Illinois. In its dirty front window, a sun-faded hand-written sign had been taped. For years, the sign remained, corners curling more with every passing season. It read, WANTED: RECORDS by LOTHAR and the HAND PEOPLE.