The Talented Ms. Highsmith

Two old photos of the young Patricia Highsmith taken during the summer of 1942 depict her—aged twenty-one, just after graduating Barnard College—as a kind of a sphinx. In one photo, the wild-haired, extremely handsome, tomboyish young woman sports an expression like that of the proverbial cat who has just swallowed the canary; in the other—a nude portrait—the sylphish Highsmith looks like a hot-house flower come to life from the page of an Egon Schiele erotic watercolor sketch.

Though nominally bi-sexual, Patricia Highsmith was essentially lesbian. In reality, her sexuality was quite complex— an epic womanizer (of women both gay and straight) whom some have claimed harbored misogynistic tendencies (except in bed where she has been described as a formidable lover) towards her mentors and muses. It is quite possible that she ultimately came to see herself as a man trapped in a woman’s body.

“Patricia Highsmith clearly felt like an eternal outsider.”

One thing is certain—Patricia Highsmith clearly felt like an eternal outsider. After a life full of tempestuous love-trysts as a feted itinerant American novelist abroad in Europe, Patricia Highsmith left this world in 1995; a misanthropic genius and alcoholic. But the shadowed beauty that resides in her body of work renders her immortal. Graham Greene called Highsmith “the poet of apprehension,” while Gore Vidal referred to her as “one of our greatest modernist writers.”

Born in Texas in 1921, Patricia Highsmith evolved into a personality of dark intelligence and savage humor which she used exceedingly well to evoke a sense of menace in her macabre suspense fiction—most notably in Strangers On A Train (which was adapted for the screen by no less a master than Alfred Hitchcock), and The Talented Mr. Ripley (twice adapted, René Clément’s Plein Soleil, featuring the superb Alain Delon as Ripley is by far the best version).

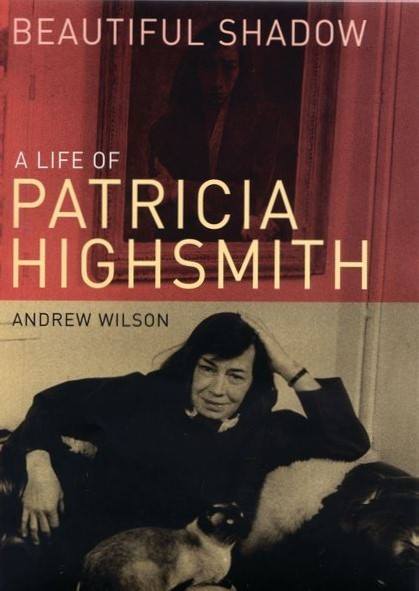

The philosophical themes and arguments at the center of Highsmith’s world of fiction are existential in nature—influenced by the case histories in Dr. Karl Menninger’s The Human Mind, as well as by the works of Dostoyevsky, Nietzsche, Kafka, Kierkegaard, Camus, and Sartre—while also grotesquely gothic and noir in the vein of early 20th Century pulp fiction novels and magazines. As biographer Andrew Wilson notes, “…she celebrated irrationality, chaos, and emotional anarchy, and regarded the criminal as the perfect example of the twentieth-century existential hero, a man she believed was ‘active, free in spirit’.”

Highsmith herself was to state: “People quest for the acquisition of the material and in doing so lose whatever spiritual life they once had. Man is at once a killer and yet possesses a moral nature; a contradiction that can only be resolved by insanity.” Highsmith’s innovative stories touched on the duality of man and a blurring of identity, while seducing the reader into identifying with her deranged protagonists. Of all her characters the amoral aesthete Tom Ripley stands apart as both her most beloved creation—he was to star, and triumph, in five novels—and her own alter-ego: the man she would have been had she been a man.

Since Highsmith’s passing, a renewed interest in her work has led to the posthumous re-publication of most of the author’s oeuvre; and numerous film, TV, theater, and radio adaptations of her stories. Several Ripley film adaptations have occurred since 1999—Anthony Minghella’s disappointing version of The Talented Mr. Ripley, Liliana Cavani’s nicely done Ripley’s Game, (which was previously adapted by Wim Wenders as The American Friend), and Roger Spottiswoode’s Ripley Underground. Even in death, Patricia Highsmith’s beautiful shadow continues to loom large.

– Sean Mageean

Beautiful Shadow—A Life Of Patricia Highsmith, by Andrew Wilson