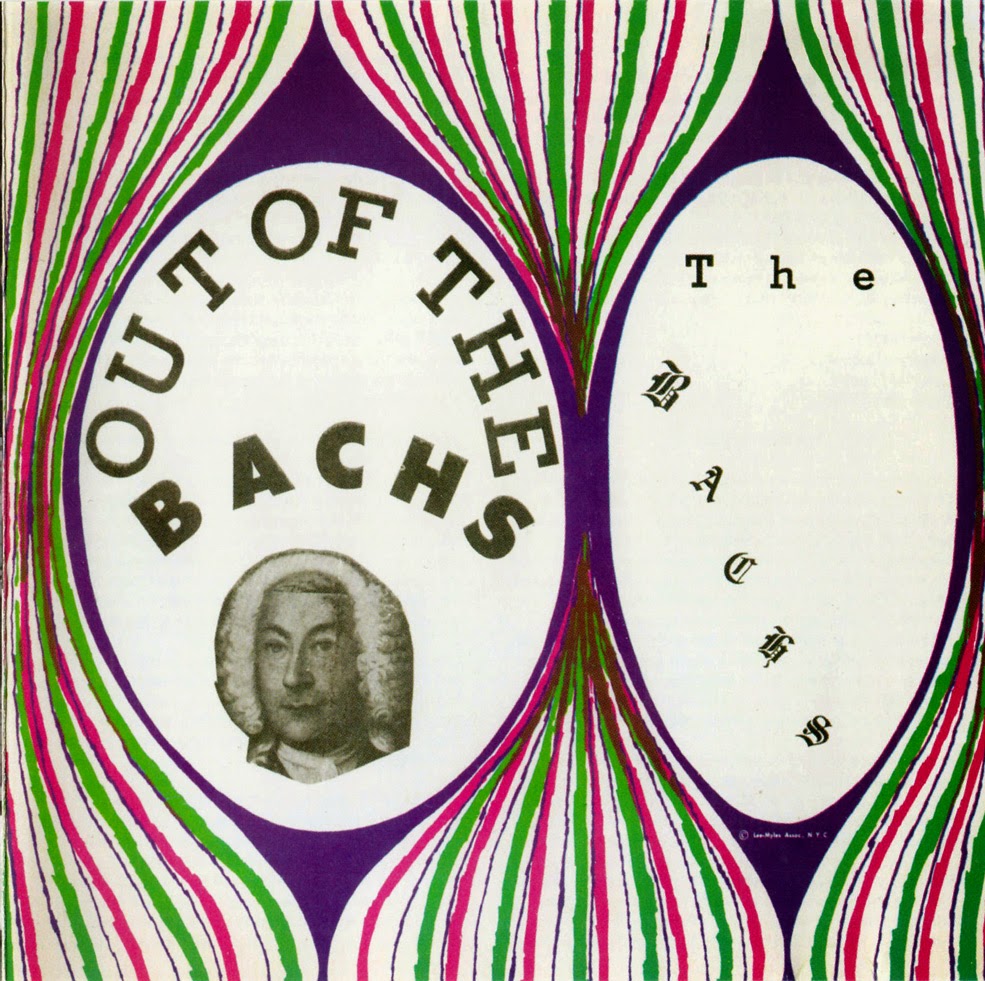

The Bachs interview

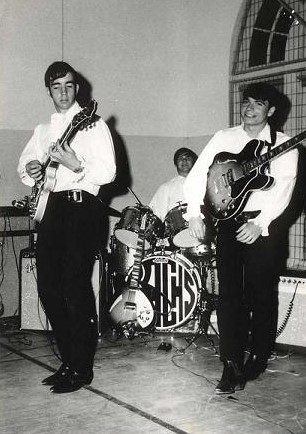

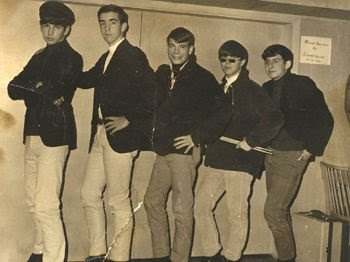

The Bachs recorded one of the rarest and most unique garage rock records of the 1960s. They were: John Peterman – Guitar and Lead Vocals, Blake Allison – Bass Guitar and Lead Vocals, John Babicz – Drums and Percussion, Mike De Have – Rhythm Guitar and Ben Harrison – Lead Guitar.

It’s great to have you.

John Peterman: Thank you for the opportunity to share my memories of this amazing time in my life. Playing with The Bachs was a joy and an honor. We had just as much fun in pre and post rehearsal as we did at our gigs. As with all memoirs, you will find agreements as well as discrepancies in the telling of our story. One thing we could all say for sure, it was a hell of a great ride. Little did we know that Out Of The Bachs would still be discussed 50 years later.

When and where were you born?

John Peterman: April 16, 1950. Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Blake Allison: October 27, 1949 in Middletown, Connecticut.

John Babicz: Born in Lake Forest, Illinois, Feb 3, 1949.

How old were you when you began playing music and what was the first instrument you played?

John Peterman: Although my father was an accomplished pianist and attempted occasional lessons on the piano, I picked up a guitar at 13 in 8th grade. No lessons, just fumbled through a Mel Bay guitar lesson book.

Blake Allison: I was either five or six when I started playing piano. My parents were professional musicians. My father was head of the music program at North Shore Country Day School in Winnetka, Illinois, and he also conducted church choirs and local vocal ensembles. My mother was an accomplished pianist and organist. She had piano students and played Sundays at the local church. She also had a fine singing voice. All four Allison siblings had to learn piano, and then, later, a second instrument early on. At age five or six, I began playing trumpet at age eight.

John Babicz: I started playing drums in 6th grade, I was in a Drum and Bugle Corps called Custers Brigade from Lake County, Illinois.

What inspired you to start playing music? Do you recall the first song you ever learned to play?

John Peterman: What prompted thousands of boys to play the guitar: The Beatles. The easiest songs to play of theirs were “Love Me Do,” “Please Please Me,” and “Twist and Shout.”

Blake Allison: As noted above, we were expected to learn to play. I don’t remember a particular early song. We sang as a family. When on road trips, we sang traditional, American folk songs like “15 Miles on the Erie Canal,” “Sweet Betsy from Pike.” We also sang Christmas carols. When I was six, I began singing in the church youth choir. I sang in choral groups all through my school years to the end of high school. In college, I sang with the Chapel Choir. Post-college, back in Lake Bluff for a year, I sang in the choir of the local, Episcopal church where my father was music director. All that public singing probably is why I was so comfortable singing in the band and being up in front of people.

John Babicz: I would say Elvis Presley and Ricky Nelson were major influences in grade school. Sandy Nelson recorded some great drum music in the 1950’s as well. The first rock song I learned was probably “Louie, Louie” by the Kingsmen, a classic song.

What bands were you a member of as a youth and what types of music did you play?

John Peterman: I was never in a band before The Bachs. Blake and I shared a love for Lennon/McCartney and would get together to strum the chords and harmonize. Michael Dehaven and I also shared a love for music and he played with other guys around the area. I think he and Ben played together and then asked me to join them. I knew that the one guy we need to add to make this band special was Blake. Our drummer at the time wasn’t cutting it and that’s when we discovered Babicz. We loved him first because he had the longest hair in Lake Forest and he was cooler than any one of us. He showed up with his bass and couldn’t play a lick. We asked him what else he could do and he got on the drum kit and played the hell out of the drums. That was it.

Blake Allison: The first band I was in, apart from the school bands, was “The Washington Squares,” named after a song by The Village Stompers that was popular at the time. That was in 1963, the fall of eighth grade. We were a ‘combo’ composed of a trombone, a drummer, a clarinet and me on trumpet. There may have been another instrument but that escapes my memory. Our only public performance was at a school dance. We played three songs: “Washington Square,” an Edie Gorme and Steve Lawrence song called “I Just Want to Stay Home and Love You” and David Rose’s “The Stripper.”

The Washington Squares did not last long. The Beatles hit the airwaves with “Please, Please Me” about the time of our first and only performance. Suddenly, everything changed for me musically. My mother’s father had an acoustic guitar. It had steel strings with very stiff action that was very hard on the fingertips, but it was all I had to play as I set off in my pursuit of Beatles music. My parents did not approve of The Beatles and did not encourage me to go in that direction.

After “The Washington Squares,” I got together with some other, rock musician wannabee classmates, and we formed a group called ‘The Phases.’ We weren’t a rock band. We had more in common with a folk group like “The Kingston Trio;” accept that in addition to the usual acoustic guitars there was a drummer. We played a couple of times in the spring of 1964 at a school-organized, dance gathering called “Teen Town.” The first time out we played three folk songs only two of which I can remember. They were “The Golden Vanity” and “The Seine.” The second time we played a more rock-oriented set of three. That was the debut of my song “That’s the Way It Goes.” We also played a song I wrote called “Oh, Elaine;” a love note to a girl on whom I dated named Elaine Gorman. She was, as you might expect, mortified.

‘The Phases’ also were short-lived; maybe four months. At one point three of us forced out a player to make room for John Peterman of bringing better singing and musicianship to the band, but “The Phases” broke up before that hope could be realized.

That was the beginning of John’s and my musical collaboration. It did not last long, because we had a falling out in the late fall of ’64, probably my fault, and did not speak to each other until the following summer.

“Everyone was looking for the same thing: a lead player who could imitate George, Keith, or Dave Davies of the Kinks.”

The Bachs were also known as The Apollos. Who were some of the artists you shared the stage with?

John Peterman: I was not part of the Apollos and the Apollos never really performed to the best of my knowledge. Everyone was looking for the same thing: a lead player who could imitate George, Keith, or Dave Davies of the Kinks. … and vocal harmonies of The Beatles. At the time, lead guitar breaks were looked upon as the measure of a great band. The guitar break in “Louie Louie” was the standard in terms of difficulty. If you couldn’t play all the Chuck Berry lead parts, you couldn’t perform live. When bands tried to play the Kinks’ “You Really Got Me” and “All Day and All of the Night” (two songs, I might add, that were way ahead of their time and laid the groundwork for Punk), we all stood around and assessed the lead player’s ability to play those chops. Few could. Ours, Ben Harrison, played those part immaculately with a ferocious tone.

Blake Allison: I was never in The Apollos. In the summer of 1964, that band was in a state of personnel transition with Peterman having just joined it. I was asked to join after John Babicz became drummer. Then they needed a bass, and I could do that. They also needed someone to help Peterman with vocals, and that was another of my strengths. At that point the roster of what would become The Bachs was set. There was Peterman on vocals and rhythm guitar. Mike DeHaven played rhythm guitar and sang back-up vocals. John Harrison was on lead guitar and back-up vocals. I sang vocals and played bass. Babicz played drums exclusively at the start but later on would have an occasional foray out front to sing something like “Hey, Little Girl” (the Syndicate of Sound) or “Little Red Riding Hood” (Sam the Sham) on bass and vocals.

Regarding ‘sharing the stage,’ we almost never did unless it was one of the few ‘battle of the bands’ in which we played. We most often played club dances and private venues. We usually were the only band.

John Babicz: I was the replacement drummer for Chuck Moburg in the Apollo days. John Harrison was tasked to fire him. I originally showed up with a bass guitar to join the group. After Chuck left early, I got on his drums and demonstrated my superior skills, the rest is history.

When did you begin writing music? What was the first song you wrote? What inspired it and did you ever perform the song live or record it?

John Peterman: I never considered writing a song until I heard Blake do it. I remember hanging out in his attic room as he spun out these beautiful chords and melodies. It was eye-opening. It seemed to come so effortlessly for him. I gave it a try and found some level of success, but I was more comfortable with writing the lyrics.

Blake Allison: I started trying to write probably when I was twelve. Those few efforts were in the style of pre-Beatle rock. The only one that comes to mind was in a country, ballad mode with a lyric about “I’m a race driver in the pits, and I’m about to call it quits.” There was another ballad with a line “the moon is up above, hold me love.”

“That’s the Way It Goes” I wrote in the spring of 1964. That’s the first one I can recall writing for singing along with a guitar. That song now has been a part of my life for 55 years. We left it off the original vinyl album, because we couldn’t get a good take.

It’s actually Peterman’s arrangement that you hear on subsequent re-issues. He did that in the summer of 1964 before I joined up with what would be “The Bachs.” I remember riding my bike past the house where “The Apollos” were practicing one summer afternoon. The windows were open, and to my surprise, they were playing a different rendering of “That’s the Way It Goes.” I thought, “Hey, that’s my song! The lyrics and melody hadn’t changed, but John had set the instrumentation up for electric guitars. I had written it on acoustic and didn’t have enhancements like reverb and a tremolo bar to modulate the sound the way you hear it now. It would become our signature song, and many of our friends who bought the original vinyl were very disappointed it wasn’t on the album. We just couldn’t get a take that conveyed the song’s energy.

John Babicz: I was not a songwriter, but I possessed a great stage presence.

How did you decided to use the name The Bachs?

John Peterman: Once we knew we were a band and had what it took to play live in the Chicagoland area, we had to come up with a name. Babicz took it upon himself to come up with about 100 names which gave us hours of x-rated amusement. I wish we still had that list somewhere. I’m pretty sure The Box was on that list along with other similar names and we decided to change the spelling to get the double entendre.

Blake Allison: Peterman and I both had classical music in our backgrounds and thought the name honored that while adding some degree of sophistication. It was Babicz who made it into a ‘double entendre.’ His slant on the name probably did the most to influence the album’s “Out of The Bachs” title.

John Babicz: It was a play on words and had multiple implications along with a tribute to a great composer.

“Hendrix changed everything.”

Who were the band’s major influences?

John Peterman: The Beatles and Stones were the primary influences. We like to cover both because we loved their music but it also gave us the opportunity to show we could do the harmonies but also the rough blues stuff. We loved The Kinks and played many of their songs live. We won a Battle of the Bands competition with The Monkees’ “Daydream Believer,” so we could play just about anything. We didn’t have a keyboard player so it made some of The Animals and similar groups material a bit harder. In our last few months we played “Foxy Lady.” But, really, Hendrix changed everything. In much the same way that The Beatles swept out artists like Brenda Lee, Hendrix put an end to many groups like ours. We loved Hendrix, but also realized that the music coming out was beginning to exceed our grasp.

Blake Allison: We played Beatles first and foremost. We also played the Stones. The Kinks were a big presence in our sets. The Byrds, The Animals and Paul Revere and the Raiders were present too. Surprisingly there were several Lovin’ Spoonful and Monkees selections on our play list as well. Of course, we did some of the Chuck Berry classics like “Carol” and “Route 66” as well as staples like “Louie, Louie.”

Some rock influences that found their way into my DNA occurred because I grew up with two older sisters. Through them I became very much aware of pop music of the late 50s and early 60s; Elvis, The Everly Brothers, Dion and the Belmonts, Frankie Avalon, Brenda Lee, Leslie Gore, The Four Seasons, and the list goes on. Add to that some of the R & B artists that influenced the Beatles and Stones. The Bachs never performed music from that era, but those songs definitely were a part of my musical being.

John Babicz: Beatles, Rolling Stones, Kinks, were the main influences. Add some Paul Revere and the Raiders and Byrds, we even did music by the Monkees.

Did The Bachs play many gigs? What were some of the venues you played? Who were some of the artists you appeared with?

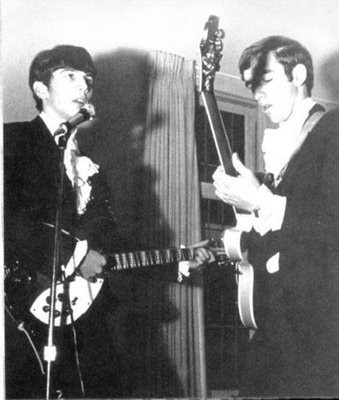

John Peterman: We played every Friday and Saturday night for a couple of years and practiced every Sunday for 3 or 4 hours. We were determined to play a great song live the weekend of the week it came out. I think we played 4 songs from Sgt. Pepper at a gig just days after the album was released. We had a playlist of 100+ songs…maybe more. Our first gig was at the Lake Forest Rec Center renamed The Cellar for the weekend nights. It was so different then. Almost every town had a venue where live bands played on the weekends. Hundreds of these places around Chicago were filled every weekend night with live music. It was the same across the country. There was no shortage of public places to play and we also played at many private parties.

Several amazing nights come to mind. I think the band members would agree that the show at New Trier High School was the high point in terms of crowd frenzy and overall playing. New Trier, at the time, was a school of 5,000 kids and it felt like half of them were in the gym that night. Our first few songs on the playlist most nights were “Kansas City” (McCartney/Beatles version), “The Last Time” (Stones), and “Long Tall Sally” (again McCartney/Beatles version which Blake could nail perfectly). When we finished those 3 the gym was bedlam. Acoustics were not great and shit was bouncing off all the walls but it was electric.

On the other end of the scale, we played at A.C Neilson’s house and I recall him coming up to us every few songs and asking us to turn it down. Whispering “Johnny B. Goode” was not fun. I think we finally said screw it and just blasted our way out the door.

Blake Allison: Yes, we played regularly from the winter of 1965 until we stopped in the spring of 1968. We played mostly teen dance venues and an occasional house party; usually on Friday or Saturday night. We played less in the summer, because there were fewer dances held. In the beginning, we charged $100 for a three-hour performance and ended up at $150 for three hours by the time we stopped. The biggest name with whom we played was Ted Nugent. He had just left “Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels” and was making a first tour with his new band “The Amboy Dukes.” Babicz seems to think it was a ‘battle of the bands’ booking and that we bested Nugent. I don’t remember it that way. I thought we were the opening act for him. I remember him telling me after we played that I had a great voice.

John Babicz: Many private parties in the Chicago and northwest suburbs. Teen clubs were all the rage: Pink Panther in Deerfield, Midnight Hour in Barrington, New Place in Algonquin, Lake Forest had weekend dances, Friday it was The Cellar, Saturday it was The Big Toe. We played almost every Friday and Saturday night.

You were doing a lot of Battle of the Bands and Chess Records approached about a recording contract,…

John Peterman: Indeed. We played two songs at the Battle of the Bands in Algonquin IL. for the opening round to get the opportunity to compete at Navy Pier in Chicago for City bragging rights. We played The Bachs tune “You’re Mine” and “Daydream Believer.” After having won that battle, we were approached by a slimy little fellow with a contract offer to record. I don’t recall it was Chess, but other bandmates might confirm that. The problem was that he (Reimer Gebauer) wanted us to record this very, very lame song he wrote and we just couldn’t make it sound right. He tried 3 of us on lead vocals, including Michael who probably came the closest to what he was looking for. But the label still wanted us and we were excited to pursue it even though we all knew we were soon going off after high school in 5 different directions. Four of our dads got together with us and patiently went over the details of the contract. In retrospect, they were very kind in their approach to let us know we were being screwed. As it turns out, Out Of The Bachs probably never would have happened had we gone ahead with that deal.

Blake Allison: Yes. As you know, Chess records was a big deal for blues R & B and pre-rock black artists. The roster included all the big names; Chuck Berry, Muddy Waters, B. B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, and the list goes on and on. We were approached by a young guy named Reimer Gebauer who had a record he thought we could do called “Silhouetted Summer Dream.” We played it live a couple of times, most notably when it was included in a taped performance of the band at Skokie Valley Junior High School in 1967. Our fathers were justifiably skeptical and wanted to meet Reimer. They scheduled a meeting at Harrison’s house, but Reimer never showed. I actually had phoned Clark Weber, a popular, radio personality on Chicago’s famed WLS Radio, to get his opinion of the project’s potential. He had heard of the song but was non-committal about whether it was the right move for us.

John Babicz: We destroyed Ted Nugent before his Amboy Dukes came out with “Journey to the Center of your Mind.” That was accomplished at the Pink Panther in Deerfield, Illinois. We won a sectional Band Battle at the New Place, won $200 equipment gift certificate, and advanced to the International Battle of the Bands in Chicago’s Navy Pier. We came in 6th out of 86 participants, a pretty good showing. The 45 we were approached about never happened, the record folks wanted us to put up advance money, our parents decided that was not so good a deal. “Silhouetted Summer Dream” is on a private recording I have a copy of it.

You still went to the studio to record your material. Was this out of your own pockets or with money you got from Battle of the Bands?

John Peterman: I think we funded the recording cost through money we made playing gigs. We had planned to pay ourselves back through the sale of the albums.

Blake Allison: We paid for the one-day session with earnings from the band’s savings account. I was the treasurer, and we had a reserve from our performances. This account was how Babicz repaid Harrison’s parents for the money they put up so he could buy a Ludwig drum set.

John Babicz: We paid $750.00 for the studio time and initial pressing of 150 copies, covers included. We all shared equally in the cost, so the money came from our efforts.

Where was the Out of the Bachs LP recorded? How long did the sessions last? Would you share some recollections from the sessions? How pleased were you with the finished product?

John Peterman: So let’s talk about Out Of The Bachs. Band member’s reaction to the finished project ranged from being very disappointed to outrageously pissed. We had in our heads what the music sounded like during playback and then the end result was nothing like what we had expected. For me, it was embarrassing. I understand that part of the charm that fans and collectors of the album have is due to raw echo chamber sound. It contributes to the authenticity of the ‘garage band’ mythology. We certainly didn’t intend for it to sound like that. The guy in the studio had only recorded choral and symphonic music and had never put a guitar or drums through his board. In addition, we did only one instrumental take and one vocal take for each track. The instrumental track was recorded ‘live’ with everyone playing together in the same room. As a result, the drums are barely audible and the mix is nonexistent. We were very naive about the recording process and were just excited to be doing it all.

John Babicz: ROTO Records was on the upper floor of a drugstore in Barrington, Illinois. We were there at least 8 hours. We laid down the instrumentals, seems like one take on each song. Then the vocals were recorded. The only song on the album that was recorded as voice and instrumental at same time is, “Answer to Yesterday.” Blake sang and played guitar, while John Harrison played the Bass. Blake wouldn’t let the rest of us in while he did that song. I named that song incidentally, as well as “My Independence Day.” I do remember that my drums were set a a low level during almost the entire album. I’ll never forgive the guys for that.

Blake Allison: As Babicz noted, the album was recorded at ROTO Records in Barrington, IL. We did the whole thing in one day. The recording technique used was ‘sound on sound.’ We would do the instrumental track and the sing the vocals over that. Peterman’s recollection pretty well sums up what we all felt to one degree or another about the result. No one was happy with the sound quality.

What was the writing and arranging process within the band?

John Peterman: In terms of the songs we covered, everybody had a say. When we got together to practice, someone would bring up a song he wanted us to learn and if we agreed, then we’d give it a try. We had no other way of recreating a song other than to listen to it and then try to reproduce it as best we could. That meant that either Ben, Blake, Mike, or I would flush out the chords, Ben would learn the lead part, Blake the bass, and Babicz the drums. We would go over it until we got it right or decide it wasn’t good enough and discard it.

As far as our own songs, it was mostly Blake who brought a new song to the band. Occasionally, he would play it for me first and we would work on the harmonies. On several songs he asked me to write the lyrics. Sometimes he just came in with the song fully baked with the exception of the lead guitar and drum parts. We would tell Ben where the lead part would go and then by the next time we met, he would have created it. The same was true for John on the drums. Once in a while Blake or I might suggest what kind of sound we were looking for, but the vast majority of guitar and drum parts were the creation of those guys.

It is obvious to me that there would not have been an Out of the Bachs album without Blake. He had an extraordinary gift for melody.

Blake Allison: Most of the chords and melodies originated with me. Peterman wrote a lot of the lyrics. Occasionally I’d have everything done, except the lead and drums. “You’re Mine” is a good example of that. “Free Fall” was Peterman’s both words and lyrics.

I’d come in with the basics, and we would flesh it out from there. Peterman’s summary of how we worked up songs by other groups that we covered is pretty thorough. We’d just sit there with a turntable and play the song over and over until we got the guitars, vocals and words right. Nothing fancy.

John Babicz: As I recall, Blake or John Peterman would come to practice with a song they had written, run through it, gives us instruction to what they were looking for, and the drum and lead parts were developed according to what they called for. We would run through it, polishing it here and there and come up with the best sound we could.

“The four of us knew we were heading our separate ways and we wanted to have a keepsake of our playing days.”

Was there anything else recorded? You never released a single to accompany your LP?

John Peterman: We never recorded anything original other than the album and didn’t release a single. I think Out of the Bachs was more an heirloom project than an attempt to become famous. The four of us knew we were heading our separate ways and we wanted to have a keepsake of our playing days. We didn’t make any attempt, as far as I can recall, to market the album or any of songs on it.

Blake Allison: No, the album was our only formal recording. I mentioned earlier a spring 1967 recording of the band at Skokie Valley Junior High in Winnetka, IL. Two of my friends ‘Chip’ Moses and Skip Wood (now, sadly, deceased) recorded the event on a reel-to-reel tape recorder. I kept the tape for many years, and finally decided everyone in the band should have a copy of the performance. I took it to a sound shop in the Boston suburb of Belmont, I was living in nearby Stoneham at the time, and had it transferred to CD. The tape was aged and brittle. It broke several times, the technician who made the transfer said. We sound good on it given the venue and the equipment. You get a respectable representation of what we sounded like live. Tracks of it are out there floating around on the internet. I’ve seen reviews and once located a few tracks. It has a memorable performance, of the Paul Revere and the Raiders, and subsequent Monkees cover hit, “Stepping Stone.”

John Babicz: There are some very raw, live, private recordings that we possess, but no other releases to the public that I know of.

Is there any unreleased material?

John Peterman: A few years ago, Blake found a recording of us playing live around 1967. It’s actually quite good, but I think the only original on that tape was “That’s The Way It Goes.”

Blake Allison: I have a bunch of songs that I’ve accumulated from my younger days. Nothing recent. I’ve toyed with the idea of working them up into an album. The working title is “Thinking Outside of The Bachs.” Stay tuned.

John Babicz: When we reunited in 2003 some new originals were written and performed in Tucson, Arizona at Club Congress, they can be viewed on YouTube listed as Out of the Bachs, there may be as many as 6 videos available. I uploaded them myself.

How many copies were pressed? Where did you sell them?

John Peterman: I don’t think the number of copies will ever be agreed upon. It’s a convenient mystery. Babicz maintains that we cut 150 and each took home 30. He could be right if we then sold each copy for $5.00 we would have made our money back for the recording. I think the number is either 100 or 125 with each of us taking home 20 or 25 LPs and selling them for $4.00. We sold some to friends and I’m pretty sure my dad strong armed some of his colleagues to make a purchase. Regardless of the overall number, it is extremely rare to find one of the original vinyl in unplayed condition. I still own 5 copies. 4 are unplayed. The other was broken with a small chunk snapped out of the side. My wife, Katherine, framed it, partially exposed out of the original cover. Also in the frame is the page from Jerry Osborne’s “The Official Price Guide to Money Records: 1000 Most Valuable Records.” We are listed at #210 right before The Beatles A Hard Days Night Promo LP. Both were listed at $2500 at the time in 1998. I’ve heard of Out of the Bachs selling for $6,000-$7,000. I think most of the guys have sold their remaining copies and I might have to do that some day as well.

Another note about the album. “That’s The Way It Goes” was by far our biggest hit with fans and most requested song at our gigs. If we had recorded a single, that song would have been on one of the two sides. When we decided to record Out Of The Bachs, we made the decision not to put that song on the album for reasons I can’t remember. I think we were tired of the song and we might have thought it would not stand up to the other tracks. This sounds like one of the self-righteous suggestions I would have made at the time, but it was a mistake. When our friends bought the LP and discovered “That’s The Way It Goes” wasn’t on it, they were like “WTF?? That’s the only reason I bought this record”. And it’s true. We probably played only a couple of the album tracks live just a few times, so our fans didn’t really know any of the songs on the LP.

Blake Allison: As Peterman notes, the number is in dispute. I think the 150 is right, but it could easily have been 100 or 125. I sold mine to family and friends. I have two in their original, unopened plastic covering. I’ve been offered up to $9K for one. Astonishing!

John Babicz: The original Out of the Bachs album had a pressing of 150 total copies. We divided them 5 ways. I gave mine to past girlfriends for obvious reasons. My only original copy is pretty beat up, but playable. Some of the guys sold them in local record store in Lake Forest, I think.

What type of gear did you use?

John Peterman: I bought a 1965 Guild S100 Polara before we started the band. I recall trying to decide between that guitar, the Gibson SG Jr, or a Fender Telecaster. The only popular band playing Fenders at the time were The Beach Boys, so I stayed away from that one. (I wish I had the ’65 Telecaster today!!). I liked the jangly sound of the Guild.

I played out of a Fender Tremolux piggy back tube amp with dual 10′ speakers. The amp had no reverb capacity so I had to buy a reverb pack which sat on top of the amp.

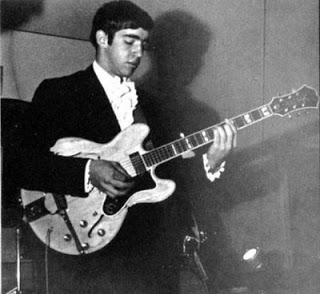

Ben was the guy with the gear. The Rickenbacker 12 String was used extensively when we played live and then on the album as well. I don’t recall which 6 string he used on the album. My guess it was a hollow body Gibson. Ben changed up his 6 string electrics frequently and unveiled them to our surprise every 6 months or so. He once traded in something like a hollow body Gretch for a Mosrite. We were all appalled since the only band we knew who used a Mosrite guitar (to great fame) was The Ventures. We gave Ben so much shit about that guitar that it was gone in a few weeks.

It is important to add here that all we accomplished would not have been possible without the generosity of the Harrison family. Ben’s parents were extraordinarily accommodating and supportive. We practiced in their lower level for untold hours over 3 years. We were loud, rude, and argumentative with each other and they never once complained. I know we were always polite and showed our appreciation to Ben’s parents, but man did they put up with a lot. We snuck in girls and booze, had raucus overnights, and never tempered it once in the basement. Ben’s dad also bought us a van to carry all our equipment around. I think he also loaned Babicz money to buy that sweet drum set, which John diligently paid back. They were very special, sweet people.

Blake Allison: I played an Eko, hollow-bodied, violin-shaped bass; the closest I could get to the Hofner McCartney used. My bass amp was an Epiphone. It was two pieces; a large case for the bottom containing a 15′ speaker. The top had the electronics (tubes, etc.,).

In addition, I had a steel-string Epiphone acoustic with a sun-burst finish similar to one John Lennon had. I used that on “Answer to Yesterday.”

I also owned a solid body, Les Paul Junior Double Cutaway with a cherry finish that I had purchased in 1964. It had a single pickup and no tremolo arm. I think I paid $125 for it. In 1976, I sold it to a graduate school classmate for $200 and thought I got a great deal. I’ve seen them on line recently selling for $4000-to-$6000. I don’t recall ever using it with The Bachs.

When we started, we mostly used Fender amps for the guitars and singing. Peterman played a Guild through a fender Tremolux. Dehaven had a Fender, solid body guitar of some type and Fender amp. Harrison played through a Vox Super Beatle and had a variety of guitars over the course of the band’s existence. When we first formed, he had a Gretsch ‘Country Gentleman’ which to our unconsulted horror, he traded off for a Mosrite solid body with a metallic finish. That didn’t last long. It totally changed our sound, and we made him get rid of it. I think the replacement was a Gibson or Epiphone hollow body in the style of the Gretsch. Babicz had a Ludwig drum kit with Ziljian cymbals. It was financed by Harrison’s father. Babicz repaid every penny from our performance earnings. When we moved up to Vox PA columns, Harrison’s parents again financed it for us until they could be repaid. Elsewhere, Peterman makes note of the tremendous generosity and kindness of Harrison’s parents. I heartily concur.

John Babicz: I had a Ludwig Hollywood drum set in Pink Champagne Sparkle, very nice. Zildian cymbals as well. We had Fender Amps and assorted other amps and guitars. We had very decent equipment for the time. Rickenbacker 12 string, Gretsch Country Gentleman, Assorted Fender and Epihpone and Gibson guitars. There are others I don’t remember the names of.

What can you tell us about artwork used for album cover?

John Peterman: I am going to admit to the crime here for the first time. The overall design with the swirly pink and green lines was presented to us as one of the few standard options for the cover from the studio. It had two open ovals on which we could put lettering or a photo. We printed the album title and our name in different fonts, but needed something else. I thought a picture of JS Bach would continue the play on words and the only place I knew to find one in short order was the Lake Forest Public Library. I found a book there with Bach’s picture and tore out the page, folded it up, put it in my pocket, and walked out. If you look closely at the Bach photo you can see where it was folded. I will now make a donation to the LFPL.

Blake Allison: The design was a stock cover that Roto Records had. Peterman cut the Bach portrait out of a dictionary. We did the lettering from pre-printed, ‘applique’ sheets from which you rubbed letters onto the surface where you wanted the words to appear.

“There is a lot of teenage, male angst about relationships.”

Would you share your insight on the albums’ tracks?

John Peterman: The attributions for songrwritng are as best as I can remember. Blake may have a better recollection.

Blake Allison: Offering an overview at the outset, as Babicz noted, there is a lot of teenage, male angst about relationships. Most of that focuses on interactions, in one state or another, that are failing or have failed. Big surprise. The songs were written by a teenager, me, who was not very good at relationships with the opposite sex.

Continuing with the age observation, remember, these songs were written, arranged, played and recorded by sub-18-year-olds. I’m not making any qualitative comparisons, but keep in mind that The Beatles were heading into their mid-20s when they began to hit their creative stride. That can make a big difference in technical ability, emotional development and experience.

“You’re Mine”

John Peterman: This is Blake’s response to all of McCartney’s and Little Richard’s rockers. It’s a great tune. Blake sang all the songs like this at our gigs: “Long Tall Sally,” “I’m Down,” etc. I love the way the song stops at the top of each verse, although if you didn’t know the tune made it a little hard to dance to. Ben’s lead parts are classic. Babicz’s drumming propels this song and we played it a lot faster live. His rolling toms are superb and Michael plays a great rhythm guitar on this cut. Music and lyrics: Blake Allison.

Blake Allison: This was my salute to McCartney’s “I’m Down,” which was his nod to Little Richard. That’s pretty apparent right from the start, although Harrison’s break has a decidedly country feel, as opposed to, the organ break in “I’m Down.”

John Babicz: Very lively, written about girlfriend dilemmas.

“Pleasure of Your Company”

John Peterman: Two things I love about this song in addition to the sweet melody. The drum fills that Babicz put in here really make the song and I love the haunting harmony in the middle and end. Music and lyrics: Blake Allison.

Blake Allison: The title of the song came before the melody and lyrics. I liked the sound and connotation of the phrase “pleasure of your company.” It bespoke of happy times with a loved one. Of course, the finished song is 180 degrees different; dark, resignation over a finished relationship.

John Babicz: Girlfriend interactions.

“Free Fall”

John Peterman: I like the way this song just drops in your lap with the title and the F major to Em chords. Blake’s splendid McCartneyesque running bass line keeps this baby moving into Ben’s Roger McGuinn Byrds style lead part. This is the one song that benefits from the echo chamber. Harmonies are sweet and the lyrics offer a few options for stoners to contemplate. Music and lyrics: John Peterman.

Blake Allison: This was John’s composition; very flowing, lyrical and upbeat. I helped out with the harmony on the refrain. Harrison is playing his Rickenbacker 12 on the psychedelic-tinged break. My bass line is very much in the McCartney mode ala the moving line underpinning “Nowhere Man.”

John Babicz: Teenage angst.

“I See Her”

John Peterman: A country song? Yeah, well maybe. Clocking in at 1:37 with nice harmonies all the way through and Ben adding the country tinges. Michael again on propulsive rhythm guitar. Of all the songs, this probably got the worst recording job. You can barely hear the drums. And you can actually hear the guy slide the volume up twice in the middle parts. Music: Allison Lyrics: Peterman.

Blake Allison: From start to finish, straight up country. I was trying to capture something lively in the style of “I’ve Just Seen a Face.”

John Babicz: Country-based, believe it or not.

“My Independence Day”

John Peterman: This is one crazy ass song. I think it is one of the first songs that combined two overlaying melodies in different time signatures. I have no idea where Blake come up with the haunting opening bass part which sets the tone for the song, but it is so cool. Music: Allison Lyrics: Allison/Peterman.

Blake Allison: This is one of my songs where the chord progression came to mind first, and then I wrote a melody on top of it. That’s sometimes how I would write. “Tables of Grass Fields” is another example of chord progression first, melody next. “Must have been the 4th of May, my Independence Day” was word play on the 4th of July; the inspiration for all the song’s somewhat defiant lyrics and mood. I’m doing another McCartney driven bass line. This time the influence was his segment of “Day in the Life.” Yes, I think Peterman is correct that it was the first rock song to employ the device of overlaying the song’s two separate, melodic elements.

John Babicz: The masterpiece of the album. I named this song. Freeing oneself from a cheating girlfriend, put not totally convinced it should be over.

“Minister to a Mind Diseased”

John Peterman: From Macbeth:

“Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased, pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow, raze out the written troubles of the brain, and with some sweet oblivious antidote cleanse the stuffed bosom of that perilous stuff which weighs upon her heart. Doctor: Therein the patient must minister to himself.” And that’s how this song got its title. I just changed the verb to a noun and there you have it. It’s a protest song, maybe. Note the ferocious bass part on the refrain and then Ben’s capstone shredding lead part with Blake’s running out the door bass. Also note a 2:35 in the song I mess up the words…one take is all we could afford. Music: Allison/Peterman Lyrics: Peterman.

Blake Allison: John came up with title, as he noted, and the lyrics too. The tone is somewhat defiant and judgmental in quality. “Of course, you eat to live, or is that live to eat.” “I’ll drive my car at 65, and nobody there will catch me alive.” The instrumentation, especially Harrison’s guitar break, references West Coast psychedelia. If you listen closely, you’ll hear me every once and a while playing some chords on the bass.

John Babicz: Great song! Teenage rebellion, living on the edge, more teenage angst.

“Tables of Grass Fields”

John Peterman: My favorite Bachs song and the best recording on the album. The opening is so splendid with Ben’s Rickenbacker chiming, Babicz’s drum rolls, then Blake McCartneyesque bass line entry…just the best. Babicz rolls through the whole song but then plays a quiet cymbal beat for Blake’s vocal: “Why don’t you come down..”…Then Ben’s brilliant backing of Blake’s “To see if there is love”…jumping right back into “Feeling Okay…”

I loved singing this song and when we got to the end…well we just didn’t want it to end. So the coda and the echo. I have no recollection of how the title of this song came to be. Maybe that’s just as well.

Music: Allison Lyrics Peterman.

Blake Allison: I mentioned above that the chord progression came first. John wrote the verse lyrics, and I wrote the refrain. We were trying to capture a more lyrical side of the psychedelic style. Babicz came up with drum roll motif underlying the closing strain.

Note that this song was written in the 1967 range when rock was pushing beyond its traditional boundaries. The musical genres that influenced the early development of The Beatles and Stones among others – R & B, Chuck Berry and Country – were being swept away by psychedelic influences and a general wave of experimentation. We weren’t immune to those influences. Of course, drifting away from the rock’s core canon, had the unintended consequence of producing music that was less danceable. We never played many of the album’s tracks at parties. I think “That’s the Way It Goes,” “You’re Mine” and “Minister to a Mind Diseased” are the only ones we did use. Most of the album was never heard in public until 2006 when we performed several of the songs at a one-off performance at Tucson’s “Club Congress.”

John Babicz: Love and something taken to make you mellow.

“Show Me That You Want To Go Home”

John Peterman: The kick of this song was supposed to be the Fuzz Bass similar to The Beatles “Think for Yourself.” But it got buried in the recording. A bit more sexual innuendo in this song to keep the fans happy. I love Babicz’s machine gun rat-a-tat all the through. Music: Allison Lyrics: Peterman.

Blake Allison: Here’s one where the opening, guitar statement was the catalyst for everything that followed. I’m playing my bass through a fuzz tone. Guitar enhancements were, at that point. still novel. Prior to the fuzz tone, the tremolo arm on a solid-body, six string guitar and reverb were about all there was for modifying a guitar’s sound. By the time of “Revolver,” that was changing. There were guitars that could make different sounds such as the Vox ‘Guitar Organ’ heard on “I’m Only Sleeping.” By 1967, the wah-wah peddle had arrived notably used by Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton. Sound modification was being done in the recording studio too.

John Babicz: Girl problems.

“Sitting”

John Peterman: This is such an sweet song. Love the harmonies and Ben’s Rick. I’m guessing one of Blake’s earliest compositions. Again with the countermelodies. Music and Lyrics: Allison.

Blake Allison: The twelve-string riff opener was the foundation on which the rest of the song was built. Again, I employed the duo, melody lines ‘overlay’ effect in the closing passage.

John Babicz: Sadness over love lost.

“Nevermore”

John Peterman: Babicz is proud to say he named this song which came from Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Raven.” On a few late nights, we would request a reading from Michael. It was chilling. The craziest part of this song is that the sweet melody is completely destroyed by Ben’s solo…”Oh the pain”…explosion!! and then returning to resigned melancholy. Music and Lyrics: Allison.

Blake Allison: The opening of “Strawberry Fields” and Lennon’s melodic line in the verse section were clearly on my mind when this was written. It’s been transcribed for guitar and the chord progression paraphrases Lennon’s melody. Again, there is a strong psychedelic character to Harrison’s guitar break.

John Babicz: More love lost.

“Answer to Yesterday”

John Peterman: It was indeed. Ben on bass, Blake on guitar and the rest of us out of the room when they recorded it. It is quite beautiful. Blake’s aching vocal on this song is truly haunting. Music and Lyrics: Allison.

Blake Allison: The idea for this song came to me when I was riding the train from Lake Bluff to Winnetka where I attended North Shore Country Day School. I wanted a melody to mimic the style of a Bach Chorale; a very straightforward, unembellished line. When it was recorded for the album, Harrison played bass, because I was having trouble concentrating and kept flubbing the lyrics. When I played my acoustic Epiphone, we got the result in one take. We did the song ‘live,’ meaning it was not sound-on-sound. It was the only song on the album done that way. Incidentally, Harrison had never heard the song before had to learn the bass part on the spot.

The title has two meanings. The first being the singer’s lament that he can’t find an answer to what went wrong with the relationship described by the lyrics. The second was my rueful acknowledgement I would never write a song as good as McCartney’s “Yesterday.”

John Babicz: We need to be together again.

“I’m a Little Boy”

John Peterman: So after the “Yesterday” ballad, we get nasty again. A tribute to John Lennon. And yes it is a song bashing gay conversion therapy before we even knew what that was at that time. The song gives a sarcastic treatment …”if you stop me you know I will be glad”. We’ll let the title stand for others the figure out. The song’s high point for me is when Ben plays in a style of Jefferson Airplane’s Jorma Kaukonen on the lead part, especially when he grovels around in those low notes. I recall all of us learning this song and then asking Ben to come up with a lead part and we would get together again to nail it down. A few days later, when Ben played this for the first time, we all just stood there and gaped at him. He said something like “well, is that good enough”? Holy shit. Also another great example of Babicz and Ben just playing off each other in such a great way. Music: Allison/Peterman Lyrics: Peterman.

Blake Allison: This is in some ways the most unusual song on the album. It is the most ‘free style’ in character; definitely showing psychedelic influences in the break. That was all a Harrison improvisation in a San Francisco mode. Even the guitar’s sound was set to evoke that West Coast sensibility. At the same time, it is structurally very controlled. There is only one chord progression throughout the sung parts. There is no refrain and no sung bridge section. It also is the only song on the record on which we used a fade out at the end.

John Babicz: This was supposed to be a more or less homophobic tribute, great lead guitar part, way ahead of 1968.

Would you mind answering question about psychoactive substances? Did in your opinion psychoactive or hallucinogenic drugs play a large role in the songwriting, recording or performance processes?

John Peterman: You would think so after listening to the album. But, no. I can safely say that Blake, Ben, and Babicz did not smoke weed or partake in any drugs other than occasional alcohol. All their gifts came from within. I smoked some pot a few times before we recorded the album that might have given inspiration to some lyrics, but basically we were pretty straight kids. Aside from a few spectacles by Michael, we always played our gigs sober and straight.

Blake Allison: I never used any hallucinogenic drugs. The first time I smoked marijuana was with other band members in the spring of ’68 around the time of high school graduation. I didn’t even drink beer or liquor until late in my senior year. I never, to any extent, was a marijuana smoker. I didn’t like the taste the smoke left in my mouth. Same with cigars and cigarettes. Stimulants played no role in my songwriting, and I never drank before playing.

John Babicz: There were many great bands in the Chicago area. The Cryan Shames, Buckinghams, The Flock(later to become Chicago), there were so many that we played with or battled against, it was a joyous time to be a rock musician.

Did local scene have any role in shaping you as a musician? Any local bands you liked?

John Peterman: Not really. I liked a couple of songs by The Buckinghams, but I would say all my influences came from groups like The Beatles, Stones, Animals, Kinks, etc.

Blake Allison: The local scene had very little impact on me musically. I liked the Shadows of Night version of “Gloria,” more so than the Van Morisson original. We played “Gloria” a lot. The Buckinham’s were, of course, very popular, but I never wrote a song in their genre trying to ride their coattails nor did any of their songs appear in our set lists. British bands had much more of an impact shaping my musical development.

John Babicz: I did not do drugs in my high school years, I did try marijuana during those years, but it wasn’t for me. We were beer and Southern Comfort consumers.

“It’s worth taking a minute to note that one of the reasons the band worked so well was our supportive, respectful interaction with each other and that each person individually had a distinct contribution to the whole.”

To what do you attribute the album continuing to be held in such high esteem among music collectors?

John Peterman: I mean it is a totally unique album in many ways. The songwriting is eclectic and, at times, masterful. The timing of the music falls into a particularly distinctive time period in music…on the cusp of Hendrix and the waning of the British invasion. The butchered recording is a key element for many…either charming or offensive. The fact that there are so few original albums certainly signaled some collectors to search for the album and then many of them found the hidden treasure.

Blake Allison: Its authenticity. Yes, many of the songs bespeak recognizable genres such as the distinctive, Country style instrumentation and melody of “I See Her” and the obvious psychedelic influences I’ve mentioned. But much of what was written was born of a conscious effort to say things in a distinctive and original way whether it was chord progressions or laying one melody over another.

Just the same, I do confess being puzzled by its longevity. The songs have held up well, but I don’t think there are any that warrant being enshrined somewhere, with maybe the exception of “That’s the Way It Goes” or “Tables of Grass Fields.” They both still sound fresh 55 years later; especially “That’s the Way It Goes” with its great tag line “Everybody knows, that’s the way it goes. That’s the way it goes.”

It’s worth taking a minute to note that one of the reasons the band worked so well was our supportive, respectful interaction with each other and that each person individually had a distinct contribution to the whole. Babicz provided the foundation with his solid drumming. Harrison always rose to the occasion providing the very important lead guitar breaks. Peterman’s singing was key. He had a broad range and was very expressive. He could knock out a very credible “Route 66” ala Jagger but also was capable of offering very emotive, understated ballads such as the Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Darling Be Home Soon.”

John Babicz: The songs were unbelievable, written by young teenagers, where did Blake Allison and John Peterman acquire this gift. Their fathers and mothers were very accomplished musicians, but it goes beyond that. I’m very honored to have played with them and been their brother for these 50 years.

Have you been involved in any musical endeavors following the dissolution of the band?

John Peterman: Nothing like those days, that’s for sure.

Blake Allison: Yes, I had good fortune in that regard. In the spring of my senior year in college (1972), four guys who had worked up a band asked if I would join them to sing lead vocals. They had a bassist already, so they asked if I would play rhythm guitar. That part of it was uncharted territory for me. We practiced for a couple of months, mostly late night into the 2:00 a.m. range, and then performed once at one of the fraternities. Our set covered a broad range of genres from early Stones, Beatles and Kinks to more contemporary, for then, groups such as The Dead, The Band and Cream. I sang almost all the leads and managed to do a credible job on rhythm playing the moving parts on “Badge” and “Drive My Car” for example. They all were good musicians, and we were very well received.

The story of that band, called ‘Blackwall Hitch,’ did not end there, however. In the winter of 2017, with our 45th reunion approaching, one of the players, proposed that we reunite and play at the class dinner. The intent was to replicate a CD compilation our class had put together for our 2002 reunion. It was based on a vote by classmates regarding their favorite songs from the era of our tenure at Wesleyan; 1968 – 1972. The list was wide ranging including The Chamber Brothers “Time,” “The Weight,” “Let It Be,” “Pinball Wizard,” and “All Along the Watchtower.” We had a couple of early sessions in March and April, but the big push was three consecutive, six hours a day sessions, just before the reunion. It was recorded, and the whole performance can be seen on the Bandcamp website. As with our 1972 performance, I sang most of the leads, although we had to recruit a talented female rocker to handle the Janis Joplin “Take a Little Piece of My Heart On” and some of the high notes my diminished range no longer could handle. This time I played bass, because we couldn’t locate the fellow who played with us back then. It was a real gift to play with those guys again after 45 years, and never did I think I’d ever get to sing “Layla” in front of an audience.

John Babicz: It would have been a hard act to follow.

“All the times we Bachs were together were special. We had a great chemistry and we really loved each other, most of the time anyway.”

Would you discuss some of your most memorable moments in The Bachs and what made them so?

John Peterman: The band worked very hard to get to where we were when we recorded Out Of The Bachs. Even though we were five very different guys who didn’t hang out much together in high school, we came together 3 or 4 times a week to play music. We respected each other and we never let anyone get too serious about themselves. Aside from playing some great gigs, we also had memorable nights together after the music. The girls came around which was always fun. On several occasions, we locked Ben out of his house where we practiced. He was a good-natured foil.

Blake Allison: I agree with Peterman that playing in front of that New Trier High School throng our senior year was a real highlight. People were dancing and watching. It wasn’t the screaming crowd of young teenage girls ala The Beatles, but it was the closest we ever got to experiencing the dynamics of playing to a large audience.

Frankly, the other truly memorable part of being in The Bachs experience was getting back together in 2003 and re-experiencing the special bond we had formed practicing and playing together all those years ago back in Lake Forest. The chemistry and comradery rejuvenated almost instantly.

The occasion was a 35th Lake Forest High School reunion. We hadn’t seen each other in at least 30 years. In the case of Babicz and Harrison, it was for me even longer; not since graduation from high school. Babicz, Harrison and their wives came out to the Boston area in August, and we practiced five consecutive week nights before playing Saturday night in front of an audience at Brookwood School where Peterman was headmaster. We gave a credible performance. We gathered in Lake Forest for the reunion in early October playing Saturday night after three-hour practice sessions Friday and Saturday afternoon. We played very well to the astonishment and delight of our classmates. There’s an audio-visual recording somewhere that was never put into finished form.

That was not the end of the story, however. We would get together four more times thereafter. The first was at my 2005 wedding in Hanover, NH. Then, in June 2006, we played at Peterman’s wedding in Belgrade Lakes, Maine. That was followed a few months later, in the same year, by a trip to Lake Tahoe to play at the wedding of Peterman’s sister Mary. She was a few years older than us and wanted music from her high school years which meant we had to learn songs by the Everly Brothers, Elvis and Del Shannon among others.

The crowning moment of that heady run, came in March 2006 when we were to play in a legitimate club venue; Club Congress in Tucson. Imagine, nearly 40 years after we stopped playing, getting paid to perform in front of a live audience! Babicz arranged that opportunity. We gathered in Tucson several days in advance of the show to rehearse. Babicz and Harrison lived in Tucson which made the logistics somewhat easier. Also, Babicz had a friend with a studio that we were able to use for practice. We played a two-hour set that included many selections off the album; the only time most of them were ever performed publicly. The club DJ said we gave a very credible performance that evoked the sound and sensibility of mid-60s rock.

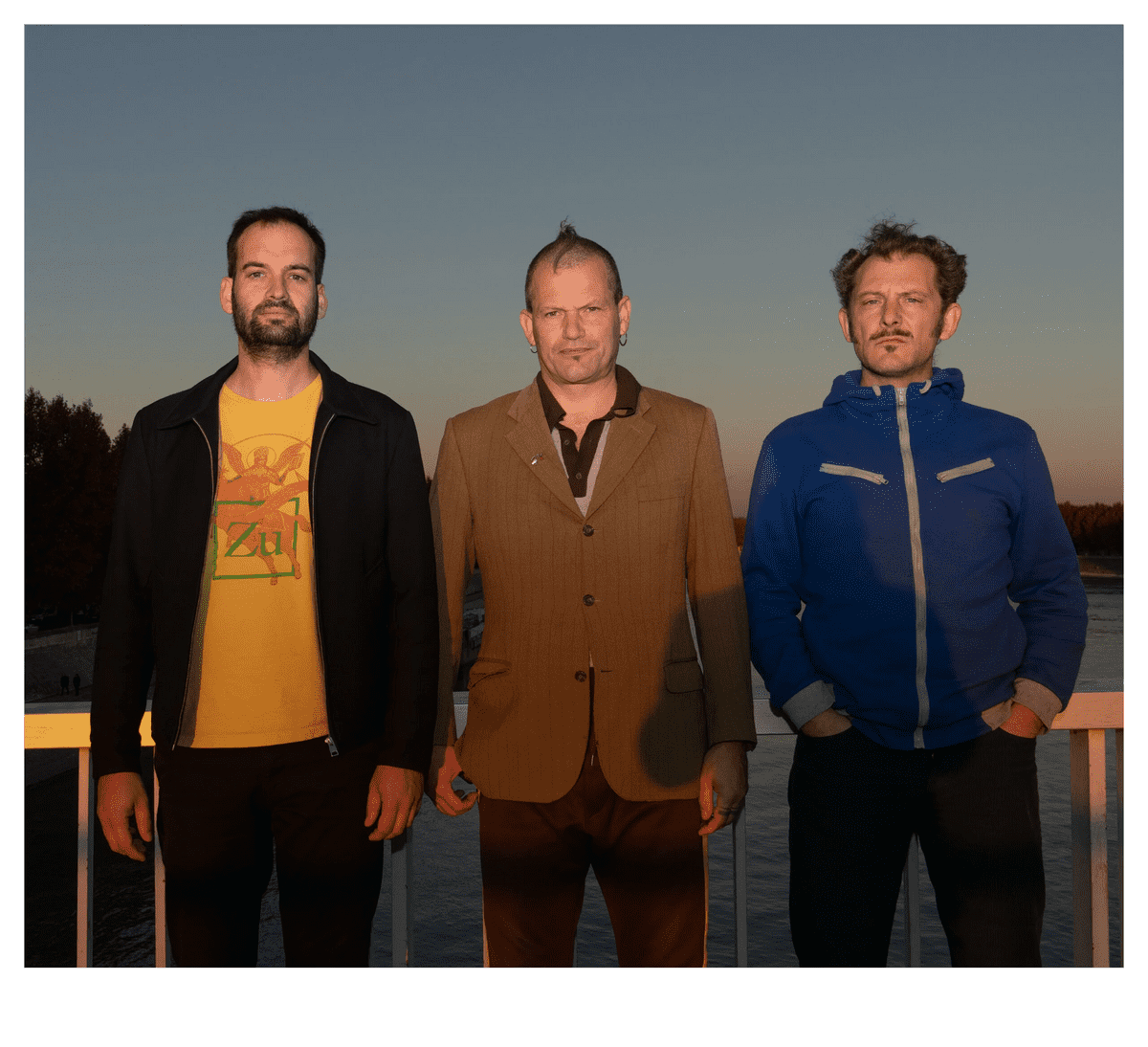

Unfortunately, this fairy tale, magical revival did not have a happy ending. In the fall of 2010, Harrison learned he had lung cancer; a diagnosis made all the more stunning, because he was a non-smoker his whole life. His initial response to treatment was good, but later on it appeared there would be no good outcome. In the summer of 2012, we four gathered in Tucson to share what was likely one last time together. We had an early evening singing session with Peterman and I playing guitars and Babicz on tambourine. Harrison clearly appreciated the music even in his weakened state. We’d been playing about an hour, when to everyone’s amazement, he got up from his chair, said, “So OK, let’s go.” He went and got his guitar and proceeded to play with us for more than a half hour. Harrison, affectionately known as ‘Ben,’ passed away right around Thanksgiving of the same year. The three, remaining Bachs gathered again in Tucson in January 2013 for his memorial service. At the service we shared with the attendees some recollections about Ben and the Bachs. It was capped off by us singing Donovan’s “Try and Catch the Wind” which was Harrison’s signature song. It was a very bitter-sweet moment.

John Babicz: All the times we Bachs were together were special. We had a great chemistry and we really loved each other, most of the time anyway.

Thank you so much for sharing your story with us. Last word is yours.

John Peterman: Important to note that what you hear on the record is not real who we were as a band. With the exception of one or two, we never played those songs live. They were written late in our career, some just for the album. We were a cover band with only one original we played from the start..”That’s the Way it Goes.”

It was also a great thrill to get the band back together around the turn of the century to perform again. Most of us had not seen each other for 35 years. When we started playing again, it all came back…everything. The sound, the jokes, the respect, the bullshitting.

Years after John Lennon died, someone asked George if the Beatles would ever consider getting back together. He replied, “Not as long as John remains dead.” And also true of The Bachs. We all miss Ben and The Bachs now only exist in memory and on that very special record.

“It wasn’t just the music that was changing. The way it was seen and heard was evolving too.”

Blake Allison: I often wonder what The Bachs would have done musically had we stayed together after high school. The rock scene was evolving very fast; fracturing into many different idioms. How would we have remained relevant? Clearly, Hendrix and heavy metal was going to be beyond us. The Motown/Atlantic rhythm and blues was not a likely opportunity either. Groups like The Band, Buffalo Springfield, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, The Eagles and The Stones certainly would have provided plenty of material for us to play. But where? It wasn’t just the music that was changing. The way it was seen and heard was evolving too. Kids didn’t dance as much. Live music was increasingly watched. The vast, local, teen dance club scene of the mid-60s was disappearing. How would we have adjusted, re-invented ourselves, as our traditional role as a dance band faded?

Maybe it was just as well that we stopped when we did. We’d had our moment within the context of a great musical and cultural upheaval. It was an amazingly creative and stimulating time to be an aspiring, rock musician. Out of the Bachs, with its songs touching many of the genres of that remarkable era, in many regards encapsulated that moment and its music.

– Klemen Breznikar

It’s really moving to have these guys sharing their recollections, memories and experiences after all these years, given we talk about a band that made a local privately pressed album. Maybe sometimes how much rare is an album, creates a myth about a band – but the guys had strong music and the myth is justified. There are many people who do appreciate these kind of privately pressed records for their geniune sincerity and authedicity, and for what they were as a immortalisation of their special time.

Thanks a lot for this interview.

Plus this interview put an end to the rumor I had read back in ’94, that this album was recorded in a butcher shop! Haha!