DOM interview with Gabor Baksay

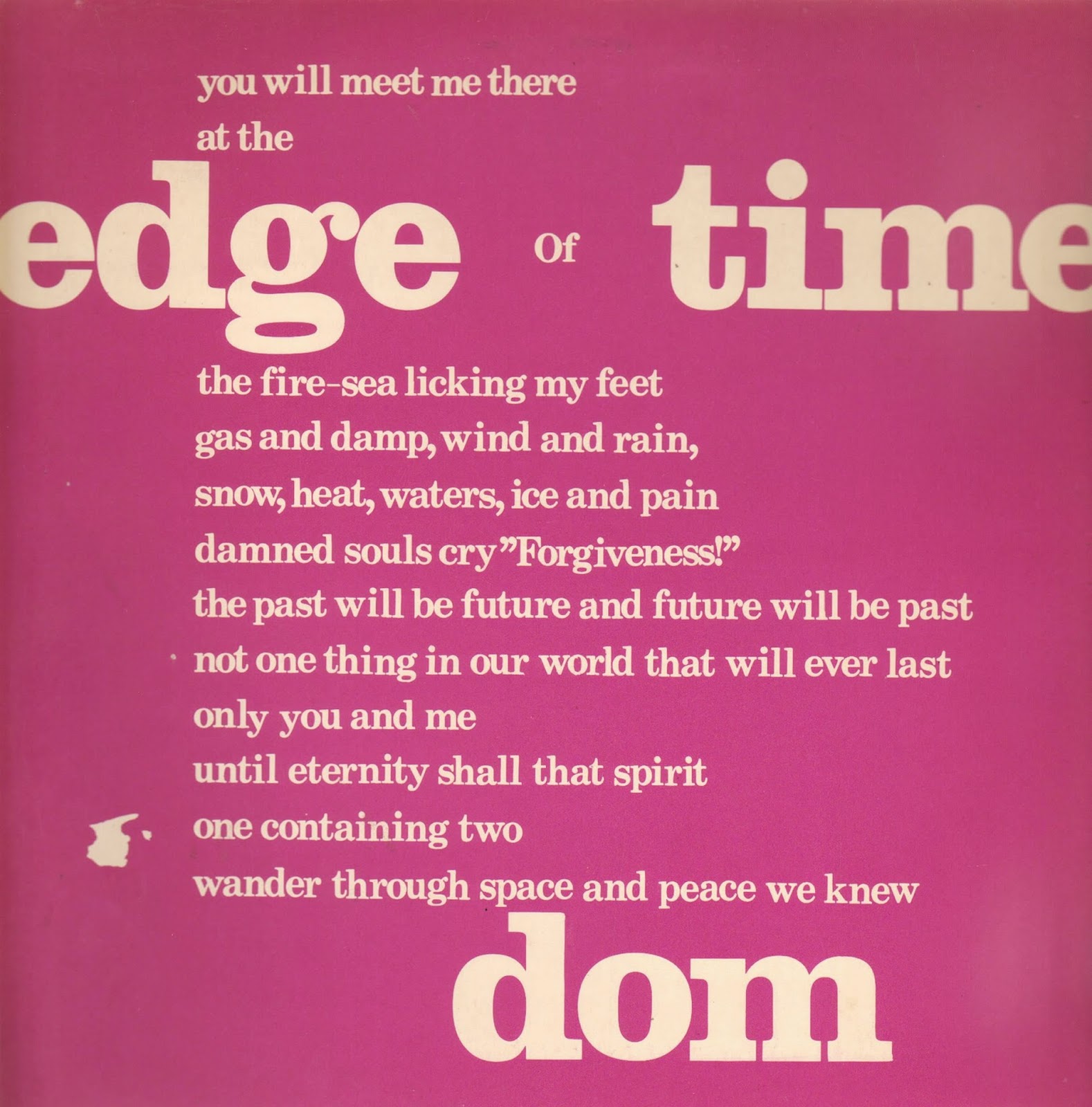

DOM recorded one of the most psychedelic albums of all time. They were from Düsseldorf and recorded Edge of Time in the early 1970s.

What was the inspiration to become a musician?

I spent my first four years in Budapest, Hungary until my mother could escape together with me to Austria during the chaotic days of the people’s revolt in 1956 against the Russian occupiers. For some days the borders were not guarded very well and some farmers told my mother the night before we left, that she should give me some wine to keep me calm and quiet. Well, the effect was the exact opposite. I wasn’t calm, in fact (that’s what I was told). I insisted on getting more wine, molesting a farmer’s wife, behaving like a hooligan and singing really vulgar songs… for a four year old. This corruption of traditional Hungarian songs in the spirit of Pre-Punk was my first, semi-official musical performance.

Later, during the time with DOM, there happened to be a short romantically influenced interlude in my generally more Dadaistic, Fluxus and Punk attitude towards music, to which I returned later and continued to evolve up to today.

The main problem of my early musical socialization during the early sixties was the fact, that a record by Elvis Presley cost 5 Deutsche Mark in the record store in my neighborhood, but a record by Peter Kraus (very embarrassing German pseudo-Elvis) only 3 DM.

My answer to the fateful question in those days: BEATLES OR STONES? – was clearly THE BEATLES.

The 3 most earthshaking experiences were (in this order):

1967, Hendrix, also 1967 Freak Out by The Mothers and in 1968 the true mother of invention: The movie 2001 with it’s groundbreaking score.

Between 1969 and 1973 ( I got off at Dark Side Of The Moon) there was only Pink Floyd.

We were travelling through Germany, following them from concert to concert.

Around 1973 (with a little delay) I discovered Beefheart and the Velvet Underground.

I was not interested in Punk in those days, in contradistinction to the Post-Punk that came up around 1978. Die Tödliche Doris, Mania D, Der Plan… And also a bit of Kraftwerk, mainly Radio-Aktivität.

Die ersten vier Jahre lebte ich in Budapest, Ungarn. In den chaotischen Tagen des Volksaufstands 1956 gegen die russische Besatzung waren die Grenzen ein paar Tage lang nicht richtig überwacht und meine Mutter konnte mit mir nach Österreich fliehen. In der Nacht davor empfahlen die Bauern, die unsere Flucht organisierten, mich mit Wein ruhig zu stellen. Der Effekt war aber genau gegenteilig. Ich war nicht ruhig, sondern begann – wie man mir erzählte – die Bäuerin in Hooligan-Lautstärke um mehr Wein anzupöbeln und für einen Vierjährigen ziemlich derbe Lieder zu singen. Diese Verballhornung ungarischer Volkslieder im Geiste des Prä-Punk war meine erste semiöffentliche Musikdarbietung. In der Zeit mit DOM kam es zu einem romantisch inspirierten Zwischenspiel meiner ansonsten mehr dadaistischen, fluxus – und punknahen Musikauffassung, die ich aber später wieder aufgegriffen habe und bis heute weiterverfolge.

Das Hauptproblem meiner frühen musikalischen Sozialisation in den frühen 60ern war, dass in dem Plattenladen in unserem Viertel, eine Elvis-Platte 5 Deutsche Mark gekostet hat, eine von Peter Kraus (peinlicher deutscher Möchtegern-Elvis) nur 3 DM. In der bald darauf folgenden Schicksalsfrage: Beatles oder Stones, war ich ganz klar für die Beatles.

Die drei erdbebenartigsten Schlüsselerlebnisse waren (in dieser Reihenfolge):

’67, Hendrix, ebenfalls ’67 Freak Out von den Mothers und 1968 the true mother of invention: der Film 2001 mit seinem bahnbrechenden Score. Zwischen 69 und 73 (bei Dark Side of the Moon stieg ich aus) gab es nur Pink Floyd. Wir sind denen zu jedem Konzert in Deutschland hinterher gereist. Gegen 73 dann mit Verspätung Beefheart und the Velvet Underground. Punk fand ich uninteressant, den gegen 78 aufkommenden Postpunk dagegen sehr. Die Tödliche Doris, Mania D, Der Plan usw. und auch ein bisschen Kraftwerk,hauptsächlich Radioaktivität.

Were you in any other bands before forming DOM? Did you record anything?

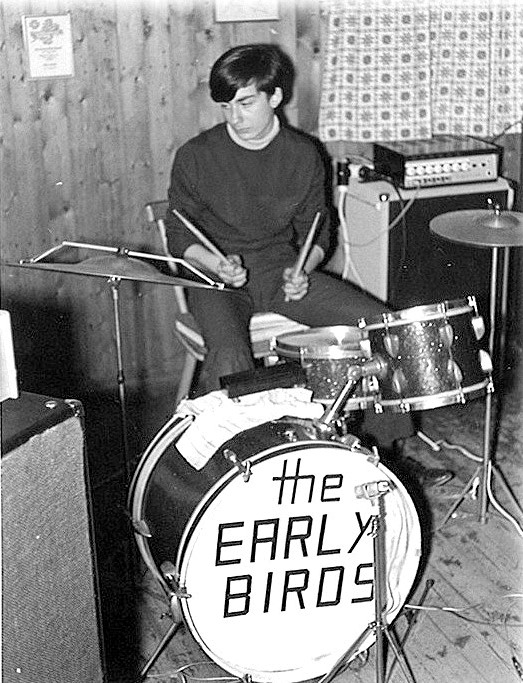

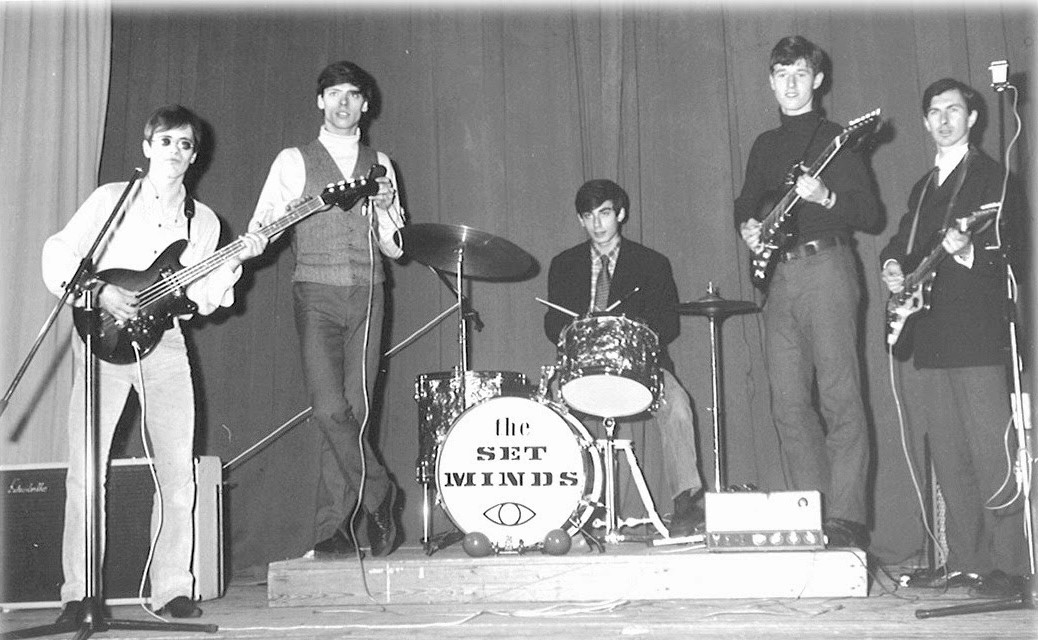

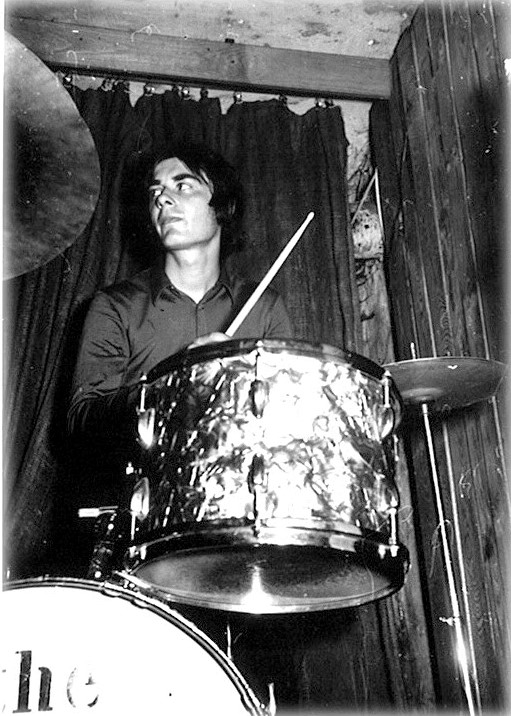

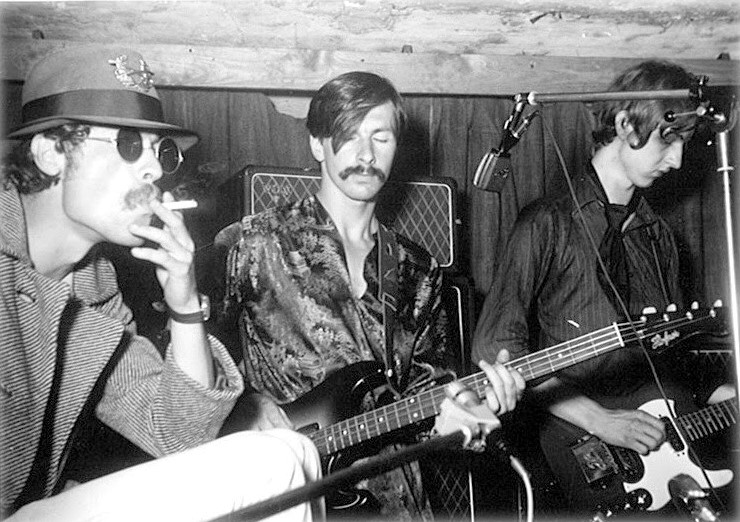

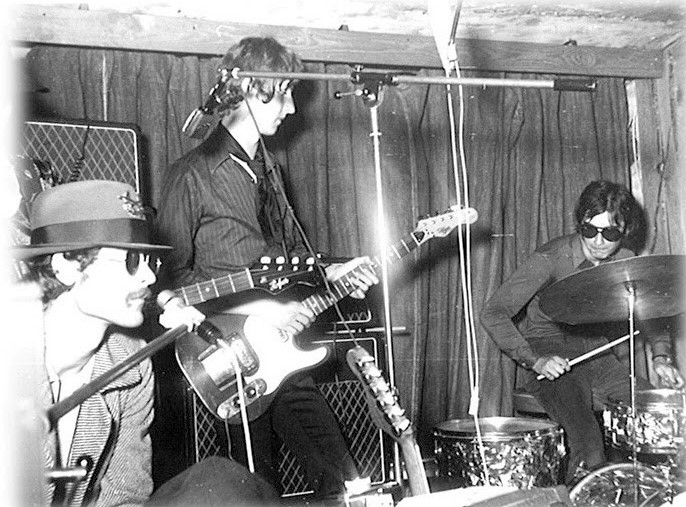

My older brother Laszlo integrated me as drummer in his Teenie-Coverband The Early Birds when I was 14. I had spent all my pocket money for my first, horrible looking drum set, which I thought looked really sexy with red frippery on the bowls. We played in sports clubs and school halls, mostly covering The Beatles. The next band was The Set Minds, which was a bit more ambitious. I was 15 and we still mainly played covers, not exclusively Beatles anymore, but also Hendrix and The Doors. My brother played rhythm guitar like he did with The Early Birds. The look of my drum set had improved a lot, the sound only a little, because of the ‘Pearls’ set I bought, which had the look of Ringo’s ‘Ludwig’ set, but sounded not much better than my first no-name-shitty-kit. Pearl was a cheap brand in those days and far away from the premium stuff they produce nowadays. Our new lead singer Klaus Lunkenheimer really managed to sound a bit like Hendrix on the Hendrix-covers we played, beside his ‘Lennon-Lookalike-Voice’.

“Around 1966/67 we were in a sort of sporty competition with Michael Rother’s Pre-‘NEU’- formation called Spirits of Sound which also included Kraftwerk drummer Wolfgang Flür.”

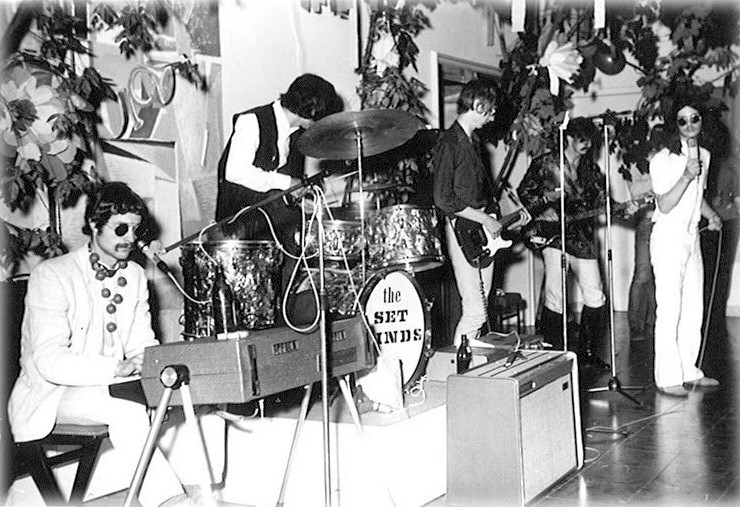

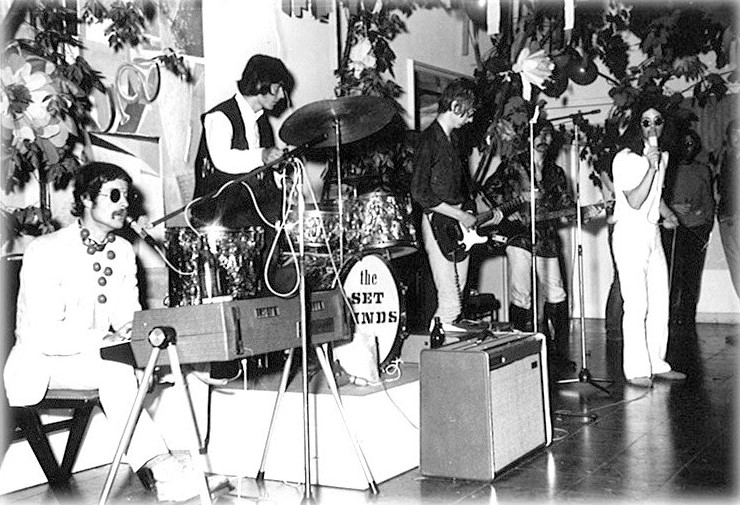

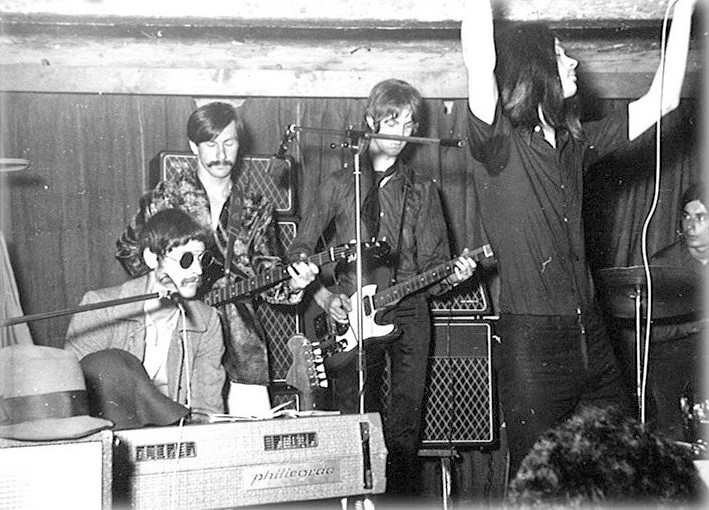

Around 1966/67 we were in a sort of sporty competition with Michael Rother’s Pre-‘NEU’- formation called Spirits of Sound which also included Kraftwerk drummer Wolfgang Flür. Both bands met each other more than once in school halls in the Düsseldorf area, performing heavy battles for the girls’ favour. The Spirits stayed ahead most of the time, because they were that small bit cooler, had longer hair, and Wolfgang Riechmann was a very charismatic lead singer. Klaus wasn’t really able to compete, because he had to go to the Bundeswehr, that has forced him to close-crop his hair. His attempts to compensate this with a sort of ‘Winnetou’- style long headdress were not really successful. The Set Minds’ ranking got higher when Hans-Georg-Stoppka und Rainer Puzalowski (later DOM) joined in 1968. Their first official act was to delete the ‘The’ and the second ‘S’ from The Set Minds. So now we were Set Mind (it was mandatory to have a name without ‘The’ or a plural ‘S’ at that time in the newly born and rising ‘Prog-Rock’ scene). Cover versions made room more and more for own material and songs, which were very heavily influenced by Pink Floyd in the beginning. Our epic 20-minute-bombastic-bouncing hymn a la “Atom Heart Mother” was called “The Planet”, which basically was an imperceptible, slow increase in the style of Ravel’s “Bolero” or “Careful with That Axe, Eugene”. My brother added some very dark, apocalyptic lyrics about a fire planet at the end of time – very close to what he later did with the lyrics of “Edge of Time”. We did have a few own songs during the The Set Minds time, but really very few and they were so obviously influenced by The Beatles. Our flagship was “There’s no Time”. The chorus was a cheeky Rip-Off from “We Can Work It Out” from The Beatles, but nobody seemed to notice that or take care, especially the composers not.

But – as mentioned before – our own songs became more and more, better and more complex because of Rainer’s and Hans-Georg’s input, so during the last period of Set Mind, around 1970, we only performed our songs.

Mein älterer Bruder Laszlo brachte mich als Schlagzeuger in seine Teenie-Coverband ‘The Early Birds’ rein. Ich war vierzehn und hatte mein gesamtes Taschengeld für mein erstes, grauenerregend schlechtes Schlagzeug ausgegeben, das aber, wie ich fand, mit rotem Flitter auf den Kesseln sexy aussah. Wir spielten in Sportvereinen, Schulaulen und coverten hauptsächlich Beatles. Die Folgeband (da war ich 15) nannte sich ‘The Set Minds’ und war schon etwas ambitionierter. Wir coverten zwar immer noch, aber immerhin nicht mehr nur Beatles, sondern auch Hendrix und die Doors. Mein Bruder war wieder dabei und spielte, wie bei den ‘Early Birds’ Rhythmusgitarre. Mein Schlagzeugset hatte sich optisch sehr aber klanglich nur ein bisschen verbessert, durch Anschaffung eines ‘Pearl’-Sets, das zwar Ringos’ ‘Ludwig’-Set bei den Beatles täuschend ähnlich sah aber nur unwesentlich besser klang als mein erstes No-Name-Schrott-Kit. Pearl war damals eine Billigmarke und weit von den Premium-Kisten entfernt, die sie heute herstellen. Wir hatten einen neuen Sänger, Klaus Lunkenheimer, der es fertig brachte, neben seiner Lennon-Lookalike-Stimme bei den Hendrix-Covern tatsächlich ein bisschen wie Hendrix zu klingen.

Wir befanden uns um 66 bis 67 herum in sportlicher Rivalität mit Michael Rothers Prä-‘Neu’-Formation ‘Spirits of Sound’, in der auch der Kraftwerk-Schlagzeuger Wolfgang Flür mitspielte. Beide Bands begegneten sich mehrfach in den Schulaulas von Düsseldorf und Umgebung zu heftigen Battles, in denen wir um die Gunst der Mädchen buhlten. Meistens lagen die ‘Spirits’ um eine Nasenlänge vorn. Die waren einfach einen Tick cooler, hatten längere Haare und mit Wolfgang Riechmann einen ziemlich charismatischen Sänger. Klaus kam da aufgrund einer tragischen Einschränkung nicht ganz mit: Er musste zu der Zeit zur Bundeswehr, die ihm das damals wichtigste sekundäre Geschlechtsmerkmal, die lange Matte, geschoren hatten, was er mehr schlecht als recht versuchte durch Anschaffung einer Langhaarperücke Marke Winnetou auszugleichen – mit, sagen wir mal, durchwachsenem Erfolg. Das ‘Set Minds’ -Ranking verbesserte sich merklich, als 1968 Hans-Georg-Stoppka und Rainer Puzalowski (später DOM) hinzu kamen. Deren erste Amtshandlung war, das ‘The’ und das zweite ‘S’ von ‘The Set Minds’ zu streichen. Wir hießen also ‘Set Mind’.(einen Namen ohne ‘The’ und ohne Plural-‘S’ zu führen war ein absolutes Muss im damals neu aufkommenden Prog-Rock!). Die Coverversionen machten immer mehr eigenem Material Platz, das zu Anfang deutlich unter dem Einfluss der frühen Pink Floyd stand. Unsere große 20-minütige Rausschmeißer-Bombast-Hymne a la “Atom Heart Mother” nannte sich bei uns “The Planet” und bestand aus einer unmerklich langsamen Steigerung im Stil von Ravels “Bolero” bzw. “Careful with That Axe, Eugene”. Mein Bruder machte dazu düstere Apokalypse-Lyrics über einen Feuerplaneten am Ende der Zeiten – ganz ähnlich wie später bei seinem Text von “Edge of Time”. Wir hatten zwar schon zu ‘The Set Minds’-Zeiten eine Handvoll eigener Stücke, aber eben nur einige, die außerdem unübersehbar unter Beatles-Einfluss standen. Unser Vorzeigestück war “There’s no Time”, dessen Refrain ein aus heutiger Sicht unglaublich dreister Rip Off von “We can work it out” von den Beatles war. Das hatte aber anscheinend niemand bemerkt, die ‘Komponisten’ am allerwenigsten. Aber, wie gesagt, durch Rainers und Hans-Georgs Einfluss wurden die eigenen Stücke mehr und auch deutlich besser oder zumindest komplexer. In der letzten Phase von ‘Set Mind’, Ab 1970, spielten wir nur noch eigene Stücke.

“Far away from space and time we did spent hours surfing on the loops…”

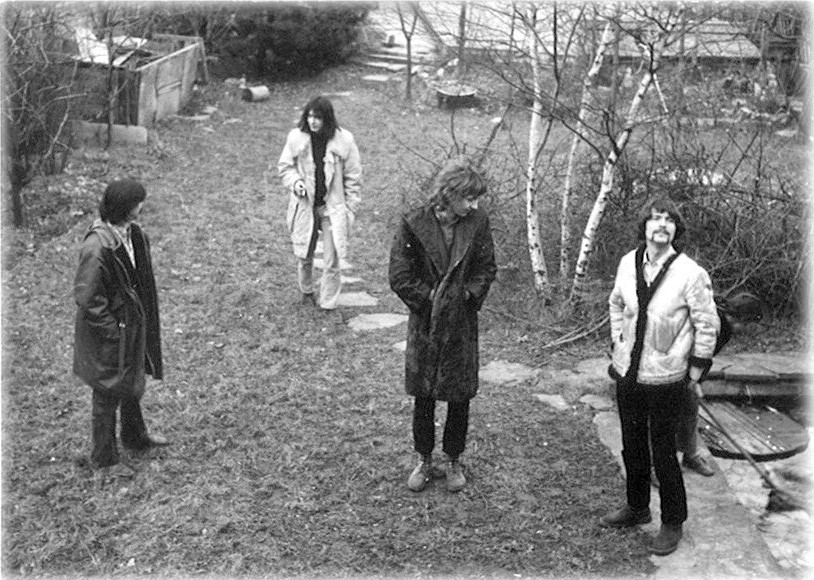

Members were from Hungary, Poland and Germany. You formed in 1969 in Düsseldorf.

There was nobody from Poland. Rainer did maybe have some Polish ancestors. My brother Laszlo and me came from Hungary, but at the time when we recorded the album, we had already been living in Düsseldorf for 10 years. DOM was born in 1970 when Set Mind did split.

Rainer and Hans-Georg left to concentrate on their own project ‘Orbit Free’ which was much more progressive. Despite the budding Psychedelic they felt that Set Mind still had some sort of ‘Pop-Group’ image. The ‘Free’ at the end was a must-have for a serious progressive Band, just like the dropped ‘S’ in ‘Set Minds’ was. I‘m sure they would have called themselves ‘Free Orbit’, if they had started one or two years earlier. Orbit Free did perform one single gig, but I haven’t been there and have no idea about other involved musicians. Laszlo completely turned his back to music and went to the CERN to do his doctorate in physics.

I had a short interlude with a Hippie-Band that played in the Spirit of the Dutch ‘Provo’- movement, looked pretty much like The Pretty Things and sounded even a bit more sharp and hard. Those guys were – compared with my more well-of ex-colleagues from Set Mind – really rude (and looked really dark on band pictures) and introduced me to hash on a concert in 1968. We scored second in a band contest and during the complete performance of the winning band I was hanging on the lips of their singer, frozen and fascinated, because the THC in my blood made it absolutely clear to me, that this suburban Hippie from Düsseldorf can only be Orpheus himself.

Rainer and Hans-Georg asked me after the gig, if I wanted to join them again.

They had split from the other Orbit Free members and continued as a duo for a short time.

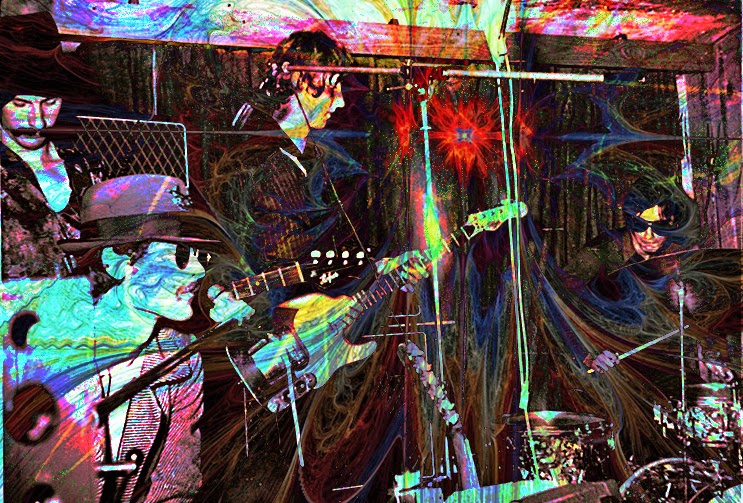

Far away from space and time we did spent hours surfing on the loops of their new Echo-Machine, benefiting from the beneficial achievements of Albert Hoffmann for the company Sandoz.

Aus Polen war niemand. Möglicherweise hatte Rainer polnische Vorfahren. Mein Bruder Laszlo und ich stammen aus Ungarn, waren zum Zeitpunkt der Plattenaufnahme aber schon seit über zehn Jahren in Düsseldorf.

DOM ist 1970 aus dem Split von ‘Set Mind’ entstanden. Rainer und Hans-Georg hatten keine Lust mehr auf das, trotz aller aufkeimenden Psychedelic, immer noch latent spürbare Image einer Pop-Gruppe und verließen die Band, um mit ihrem eigenen Projekt, ‘Orbit Free’, dem Progress in der Rock-Musik zum Durchbruch zu verhelfen. Das nach hinten gestellte ‘free’ gehörte 1970 ebenso, wie das gedroppte ‘s’ bei ‘Set Minds’ zu den absoluten must- haves einer Progressive-Band, die es ernst mit sich meinte. Ein oder zwei Jahre früher hätten sie sich zweifellos ‘Free Orbit’ genannt. ‘Orbit Free’ hatten gerade mal einen Auftritt, den ich aber nicht gesehen habe und auch nicht weiß, was für andere Musiker beteiligt waren. Laszlo ließ die Musik sein und ging zum CERN, um dort seinen Physik-Doktor zu machen.

Ich hatte ein Zwischenspiel mit einer im Geiste der niederländischen ‘Provo’-Bewegung aufspielenden Hippie-Band, die gefährlich nach den Pretty Things aussahen und auch so, wenn nicht sogar schärfer klangen. Das waren, im Gegensatz zu meinen ex-Kollegen aus gutem Hause von Set Mind, recht derbe Jungs, (weshalb sie auf Fotos so schön finster aussahen) und die mich 1968 auf einem Konzert mit Haschisch bekanntmachten. Das war so ein Bandwettbewerb, auf dem wir auf den zweiten Platz kamen. Beim Auftritt der Siegerband, hing ich deren Sänger bedingungslos fasziniert an den Lippen, weil mir das THC im Blut klar machte, dass es sich bei diesem Düsseldorfer Vorstadt-Hippie zweifellos um niemand geringeren als Orpheus persönlich handeln konnte.

Nach dem Gig fragten mich Rainer und Hans-Georg, die sich von ihren Orbit-Free-Kollegen getrennt hatten und eine Zeit lang zu zweit weiter machten, ob ich wieder bei ihnen einsteigen will. Wir hatten dann ein paar mal – jenseits von Zeit und Raum – stunden lang auf den Loops ihrer neu angeschafften Echo-Geräte gesurft und dabei ganz eindeutig von den segensreichen Errungenschaften Albert Hofmanns für die Firma Sandoz profitiert.

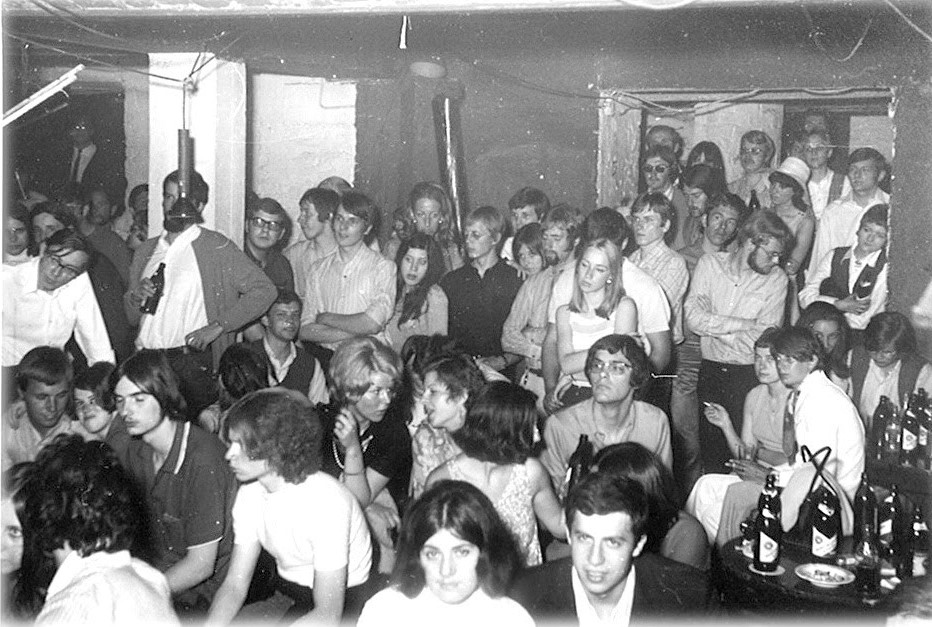

How was the scene in Düsseldorf?

Above all, the Creamcheese was the scene. A club for artists with live bands and performance, which was established by what were then Avantgarde musicians. Mainly Günter Uecker and Ferdinand Kriwet. It was a long tube that had a battery of TVs in the entry area, displaying art videos, white noise or the football world championships. The bar was designed by Heinz Mack and the barmaid was the most profligate and sophisticated in the Düsseldorf Underground. Oriental-styled, sort of Mata Hari on opium, she really was redoubtable at the time when I was 16 and my Creamcheese-era began.

“The academy of art was the hatchery for the importance of Düsseldorf as the anarchistic-avantgarde laboratory for the musical streams and evolution in the 60’s and 70’s.”

Her name was Mona I think, and she opened her own classy club later in Düsseldorf’s highly esteemed avenue (Königsallee). Really great live bands played the Creamcheese. Early Kraftwerk, still with analogue flute and a drummer that was still beating real HARDWARE, and Can were the most impressive for me. Malcolm Moroneys’s mantra recitation of ‘You Do Right’ struck me and pushed my innocent teenager mind in the right direction for ritual and holy madness forever. Playing the Creamcheese with DOM in 1971 was like winning a small Nobel Prize for us. Almost as important as the Creamcheese was the Domino, a tiny little bar only a few streets away, where you could get the best hash and have the best discussions about all kinds of art. The queen of the barmaids at the Domino also drove me totally mad, when she let off her free-speech performances in her queen-of-the-jungle outfit with her leopard-stetson. Like most of the really interesting people from the scene, she studied at the Düsseldorfer art academy, her name was Katharina Sieverding and she should later obtain world wide fame as Germany’s most important photographic artist.

The academy of art was the hatchery for the importance of Düsseldorf as the anarchistic-avantgarde laboratory for the musical streams and evolution in the 60’s and 70’s. Sure, no one from Kraftwerk, Der Plan or Neu studied there, but they all knew students or professors, and the parties at the academy were legendary. Supplementally there was the Einhorn and the Uel, places where you could chill, hang around and get something to eat if you had money. The Ratinger Hof became important at the beginning of the seventies, first as some sort of hippie-billiard-saloon, later as Germany’s most important Punk – and Postpunk club. For me, the essence of the Düsseldorf scene was the intelligent and humoristic propensity for anarchism, which was rooted primarily in 3 things:

1- the time of the French occupation of the Rheinland, which brought the rebellious esprit of the Enlightenment to the generally provincial Düsseldorf very early

2- the presence of the art academy, that was radiating deep into the scene and still today remains one of the most radical, most elitist and best in Germany

3- the ghost of Heinrich Heine, the Düsseldorf Grand Master of the ironically broken Romantic, floating above the waters of the Rhein since 1856.

It seems to me as if I could find his sensibility, mixed with his very angry sense of humour and caustic death wish in all works of bands from the Düsseldorfer school as Kraftwerk, Neu, Der Plan… and yes, maybe also DOM.

Die Szene war zuallererst das Creamcheese. Eine Künstlerkneipe mit Livebands ,von damaligen Avantgarde-Musikern gegründet: Hauptsächlich Günter Uecker und Ferdinand Kriwet. Es war ein langer Schlauch, am Eingangsbereich mit einer Batterie Fernseher ausgestattet, die weißes Rauschen, Kunstvideos oder die Fußbalweltmeisterschaft zeigten. Die Theke war vom Künstler Heinz Mack. Die Barfrau war so ziemlich das verrucht-mondänste, was der Düsseldorfer Underground zu bieten hatte. Irgendwie auf orientalisch aufgemacht, wie Mata Hari auf Opium, hatte ich mit 16, als meine Creamcheese-Ära begann, einen heiden Respekt vor ihr. Sie hieß, glaube ich, Mona und macht später so einen eigenen Edelschuppen auf der Düsseldorfer Prachtstraße (Königsallee) auf. Im Creamcheese spielten großartige Live-Bands, von denen die frühen Kraftwerk (noch mit analoger Querflöte und auf echter Hardware klopfendem Schlagzeuger) und Can bei mir den größten Eindruck gemacht haben. Malcolm Moroneys Mantra-Rezitation von “You do right” gab meinem ahnungslosen Teenager-Kopf für immer den richtigen Effet zu Ritual und heiligem Wahnsinn. Als wir 1971 mit DOM im Creamcheese spielten war das für mich, als hätten wir einen kleinen Nobelpreis gewonnen. Fast genauso wichtig war das Domino, eine winzig kleine Kneipe, ein paar Straßen weiter, in der es das beste Haschisch und den besten Kunstdiskurs der Stadt gab. Auch die Starkellnerin dort, hatte mich in höchste Verwirrung gestürzt, indem sie in ihrem verboten sexy Queen-of-the-Jungle-Zweiteiler mit Leoparden-Stetson und einem unglaublich frechen Mundwerk ein brillantes Free-Speech-Feuerwerk abfeuerte. Sie studierte, wie die meisten der wirklich interessanten Szene-Größen, an der Düsseldorfer Kunstakademie, hieß Katharina Sieverding und erlangte später als wichtigste deutsche Fotokünstlerin Weltruhm. Die Kunstakademie war ohne Zweifel die Brutstätte dessen, was die Bedeutung Düsseldorfs als anarcho-avantgardistisches Musiklabor der 60er und 70er ausmachte. Zwar war niemand von Kraftwerk, Neu oder Der Plan Student auf der Akademie aber alle kannten Studenten oder Professoren der Akademie, und die Akademiefeten waren legendär.

Ansonsten gab es das Einhorn und die Uel, Plätze wo man chillte und was aß, falls man Geld hatte. Später, Anfang der 70er wurde der Ratinger Hof wichtig. Zuerst als Hippie-Billard-Salon, später als wichtigster deutscher Punk- und Postpunkclub.

Was für mich das Wesen der Düsseldorfer Szene ausmachte, war ein intelligenter, humoriger Hang zu Anarchie. Das lag, meiner Meinung nach, hauptsächlich an folgenden Dingen:

1. an der Zeit der Französischen Besetzung des Rheinlands, die den aufmüpfigen Esprit der Aufklärung schon früh ins ansonsten eher provinzielle Düsseldorf brachte.

2. an der Anwesenheit der tief in die Szene ausstrahlenden Kunstakademie, die bis heute zu den international radikalsten, elitärsten und besten gehört und

3. auf den seit 1856 über den Wassern des Rheins schwebenden Geist des Düsseldorfer Großmeisters der ironisch gebrochenen Romantik, Heinrich Heine. Dessen Empfindsamkeit, gemischt mit bitterbösem Humor bis zu sarkastischer Todessehnsucht , meine ich in allen Werken der Düsseldorfer Schule von ‘Kraftwerk’, ‘Neu’, ‘Der Plan’ und wenn man will, auch bei ‘DOM’ wieder zu finden.

Where was the first band meeting?

My brother Laszlo took me to the lower class suburb Eller, where Rainer and Hans-Georg had a rehearsal room in his parent’s house. I was the youngest by far and I was somehow admiring Rainer Puzalowski and especially Hans-Georg Stopka. My brother took me there because The Set Minds were falling apart and we were looking for new musicians.

Ich war mit Abstand der jüngste und blickte damals ein bisschen bewundernd zu Rainer Puzalowski und besonders Hans-Georg Stopka auf, als mein Bruder Laszlo mich in den Düsseldorfer Arbeitervorort Eller mitnahm. Dort hatten die beiden im Haus von Hans-Georgs Eltern einen Proberaum. Besonders Hans-Georg mit seinem ironischen bis zynischen Humor und seiner Hipster-Attitüde flößte mir Respekt ein. Mein Bruder Laszlo hatte mich dorthin mitgenommen, weil die ‚Set Minds’ auseinander fielen und wir neue Musiker suchten.

What influenced you?

I had just become 18 when we started with DOM, and like everyone else at my age with Hippie ambitions during these times I had read Hermann Hesse and listened to the early Pink Floyd. The ‘Mothers of Invention’ were very important, even more (a bit later) ‘Captain Beefheart’, whose destruction of the groove by a rhythmically uncontrolled polyphony, remains one of the most important influences for me. In 1970 King Crimson were arriving like a bombshell on us all, especially their second album In the Wake of Poseidon. Because of the movie ‘2001-Odyssey im Weltall’ and the ‘WDR-3-HörSpielStudio’ of Klaus Schöning I was listening to a lot of contemporary music, which (because of those 2 factors of influence) appeared very intuitionally comprehensible, and not difficult or overly intellectual. It was also around 1970 that unplugged-Bands like ‘The Third Ear Band’ became more an more important for us and marked the passage from electronically generated psychedelic to analogue created forms of Romantic consciousness. I always understood the Romantic in the ambivalent form of Heinrich Heine, an I always tried to avoid sentimentalism and goo. The musical prototype for this direction was Claude Debussy, who Hans-Georg (as the only member of the band with a classical musical education) also appreciated very much.

Ferdinand Kriwet, a revolutionary artist from the art- academy-milieu in Düsseldorf was also a major influence. I want to entrust his acoustic works of art and sound collages to everyone who doesn’t know them. Kriwet was a visual artist, sound artist and author, who e.g. manufactured typographical objects and created the furnishing of the Creamcheese. He called his radio plays listening texts, and they were based upon a refined cut-up- technique with extremely rhythmic, polyphonic precision. They were not (as postulated by Burroughs) controlled by chance, they were composed. His most famous listening texts are: “One Two Two”, “Apollo America” and “Radioball”. I got to know Kriwet and his work fort the first time in 1969 while listening to Klaus Schöning’s above mentioned “HörspielStudio” on WDR 3. Schöning was very important for the acoustic art scene all around the world and brought the ‘Creme de la Crème’ of the American Avantgarde to WDR 3. His program was a must go for me and for sure beside Kriwet the major influence for my persuasion, that the differentiation between music and sound was antiquated and useless. I didn’t know John Cage in those days….. but I did in 1987, when Schöning played Cage music and interviews for 24 hours non-stop on his 75th Birthday. It was very stressful to record everything without a gap on tape, but it also was the most intensive experience I had with radio in my whole life.

Along the lines of Kriwet I started doing my own sound collages from sound pieces and snippets in 1970. I did of course not reach the virtuosity of my paragon, but I was creating acceptable material to push my friends into trance during the nights. There wasn’t much talking during these meetings. It looked more like lying on the floor, listening to my loops for hours, passing around burning medicinal herbs and KEEP OUR MOUTHS SHUT.

One of those tape recordings was planned to be used as an interlude in ‘Silence’, but this was cancelled because of my naïve attempt to include some snippets from Kriwet, for example the beginning of “One, two, two”, in which the German football reporter Herbert Zimmermann was screaming his ecstatic “Aus! Aus! Das Spiel ist aus!” during the final of the 1954 World Cup.

I had used this one plus two or three other parts without any compunction as a collage from the collage.But our producer Neubauer was going ballistic because Kriwet had recorded “One, two, two”, about a year ago with him, and he noticed the parts immediately.

“No way! We cannot use that !”

A heavy discussion followed, because I refused to accept that I have to cut those Kriwet parts out, but at the end I improvised something with shortwave-background noises, that made it’s way on the record together with Paul’s flute accompaniment.

Ich war gerade mal 18, als wir mit DOM anfingen und habe (wie damals alle in meinem Alter mit Hippie-Ambitionen) Hermann Hesse gelesen und die frühen Pink Floyd gehört. Die “Mothers of Invention” waren wichtig, noch wichtiger bald “Captain Beefheart”, dessen Zerstörung des Grooves durch eine rhythmisch unkontrollierte Polyphonie, mir bis heute zu den wichtigsten Einflussfaktoren gehört. 1970 schlug “King Crimson” bei uns allen ein wie eine Bombe, speziell noch mal deren zweite Platte “In the Wake of Poseidon”.

Dank dem Film “2001-Odyssee im Weltall” und dem “WDR-3-HörSpielStudio” von Klaus Schöning hörte ich viel zeitgenössische Musik, die mir aufgrund der beiden Einflussfaktoren gar nicht schwierig oder kopflastig erschien, sondern intuitiv verständlich. Um 1970 herum wurden für mich und die anderen unplugged-Bands wie “The Third Ear Band” wichtig und markierten den Übergang von elektronisch erzeugter Psychedelik zu analog erzeugten Formen romantischen Bewusstseins. Romantik verstand ich immer in der ambivalenten Form Heinrich Heines und wollte immer Schwulst und Gefühlssoße vermeiden. Musikalisches Vorbild in der Richtung war Claude Debussy, den auch Hans-Georg, als einzig klassisch ausgebildeter Musiker der Band, sehr schätzte.

Dann gab es in Düsseldorf einen bahnbrechenden Künstler aus dem Kunstakademie-Umfeld, namens Ferdinand Kriwett. Dessen akkustische Kunstwerke und Soundcollagen möchte ich jedem eindringlich ans Herz legen, der ihn noch nicht kennt.

Kriwet war bildender Künstler ,Tonkünstler und Autor, der u.a. typographische Objekte hergestellte und das Creamcheese eingerichtet hat. Seine Hörspiele nannte er Hörtexte, die auf verfeinerter Cut-Up-Technik mit einer unglaublich rhythmisierten, polyphonen Präzision beruhten. Sie waren nicht, wie von Borroughs gefordert, zufallsgesteuert sondern komponiert. Am bekanntesten sind seine Hörtexte: “One Two Two”, “Apollo America” und “Radioball”. Kriwet hörte ich das erste mal 1969 auf WDR 3 im oben genannten “HörspielStudio” von Klaus Schöning. Schöning war für die akustische Kunst weltweit enorm wichtig und hat die Creme de la Creme der amerikanischen Avantgarde zum WDR 3 geholt. Für mich war seine Sendung ein Pflichttermin und ganz bestimmt, neben Kriwet der wichtigste Einfluss, der mir eine Unterscheidung von Geräusch und Musik immer altmodischer und sinnloser erscheinen ließ. John Cage kannte ich damals noch nicht. 1987 aber schon, als Schöning zum 75. Geburtstag von John Cage 24 Stunden lang non-stop Cage-Musik und Interviews sendete. Es war ganz schön stressig, alles lückenlos auf Kassette mitzuschneiden aber gleichzeitig war es mein lebenslang stärkstes Radioerlebnis.

1970 begann ich nach dem Vorbild Kriwets, mittels Tonbandschnippseln Soundcollagen herzustellen. Natürlich erreichte ich nicht die Virtuosität meines Vorbilds, produzierte aber sehr akzeptables Material, mit dem ich meine Freunde in nächtliche Trancezustände versetzte. Es wurde nicht viel geredet bei diesen Zusammenkünften. Vielmehr sah es so aus, dass wir auf dem Boden liegend, meinen stundenlangen Tondandloops lauschend, uns brennende Heilkräuter weiterreichten und ansonsten die Klappe hielten.

Eigentlich sollte als Zwischenspiel bei “Silence” eines dieser Tonbandwerke enthalten sein. Das scheiterte aber, weil ich naiver Weise ein paar Soundschnippsel von Kriwet mit reingeschnitten habe, z.B. den Anfang von “One, two, two” in dem der deutsche Fußballreporter Herbert Zimmermann im Endspiel der Fußballweltmeisterschaft 1954 ekstatisch ins Mikro schrie: “Aus! Aus! Das Spiel ist aus!” Ich habe das und zwei, drei andere Stellen, als Collage der Collage ohne irgendwelche Gewissensbisse verwendet.

Das sah unser Produzent Neubauer aber anders. Zufällig hatte Kriwet “One, two, two” nämlich ein Jahr vorher bei ihm aufgenommen. Neubauer rastete völlig aus, weil er die Stellen sofort erkannte und meinte: “Das können wir nicht nehmen.” Es gab eine heftige Diskussion, in der ich nicht einsehen wollte, dass ich die Kriwet-Stellen rausschneiden soll und habe dann schnell etwas mit Kurzwellen-Hintergrundgeräuschen improvisiert, was auch mit Rainers Flötenbegleitung auf der Platte gelandet ist.

What’s the concept behind the Edge of Time?

Well, the concept was more perceived than conceived. I cannot agree to this theory, that the concept of the record was an evocation of a ‘Bad Trip’. The four pieces came into being absolutely independent from each other and were chosen very shortly before the recording. I don’t think that Rainer and Hans-Georg were following a specific CONCEPT, for sure not a narrative one. But I do agree that now – retrospectively – those four tracks seem to be made from one piece, what not necessarily means that they were contrived. It would be a very narrow-minded and absolutely NOT psychedelic understanding of music, trying to ascribe everything to a conscious intention of the musician.

Das Konzept war eher gefühlt als durchdacht. Was ich öfters lese, das Konzept der Platte sei die Beschwörung eines “Bad Trips”, kann ich nicht bestätigen. Die vier Stücke entstanden unabhängig voneinander ,und wurden erst kurz vor der Aufnahme ausgewählt. Ich glaube nicht, dass Rainer und Hans-Georg ein explizites Konzept dabei verfolgten und ganz bestimmt kein narratives. Ich gebe dir aber recht, dass im Nachhinein betrachtet, die vier Tracks wie aus einem Guss erscheinen, was aber eben nicht zwangsläufig heißt, dass sie “ausgedacht” gewesen sein müssen. Es wäre ja ein sehr engherziges Verständnis von Musik, und ganz bestimmt kein psychedelisches, alles auf bewusste Absichten des Musikers zurückführen zu wollen.

What was the songwriting process like?

Every time Rainer and Hans-Georg came over with the material that they prepared individually or together. ‘Silence’ and ‘Dream’ were more or less Rainer’s creation, ‘Edge Of Time’ a joint venture of both and ‘Introitus’ most likely the work of us all.

We were always crediting the whole band as composers, but the most style-forming stimuli came from Hans-Georg and Rainer.

Es war jedes Mal so, daß Rainer und Hans-Georg mit dem Material kamen, das sie entweder einzeln oder gemeinsam vorbereitet hatten. “Silence” war mehr Rainers Ding. “Edge of Time” ihr gemeinsames. “Dream” war klar von Rainer und “Introitus” am ehesten das Werk von uns allen. Wir haben immer die gesamte Band als Komponisten angegeben, aber die stilbildenden Impulse kamen meistens von Hans-Georg und Rainer.

How did you get signed by Melocord Records? The same company released Anima Sound, The Germs, and Rainbows.

We recorded at Studio Neubauer. He had launched an advert that he was looking for Avantgarde bands for his newly founded label. I don’t remember who he was working with, but I recall Florian Schneider tinkering on a shelving system for his setup there. I don’t know for sure what Neubauer was doing with Kraftwerk, but I remember that Michael Rother and Ferdinand Kriwet did record there. I later assumed that the Kling-Klang-Studio of Kraftwerk was the reconstructed Neubauer-Studio, because they were both located next to the main station of Düsseldorf, but I am not really sure.

Wir haben im Studio Neubauer aufgenommen. Dieser hatte eine Anzeige aufgegeben, dass er Avantgarde-Bands für sein neu gegründetes Label suchte. Mit wem er sonst noch arbeitete, weiß ich nicht mehr, erinnere mich aber, dass Florian Schneider dort an einem Regalsystem für sein Setup herumschraubte. Was genau Neubauer mit Kraftwerk machte, weiß ich nicht. Sicher weiß ich nur, dass Michael Rother und Ferdinand Kriwet dort Aufnahmen gemacht haben. Da das Neubauer-Studio am Düsseldorfer Hauptbahnhof gelegen war, habe ich später vermutet, dass Kraftwerks Kling-Klang-Studio, das ja auch in Bahnhofsnähe war, das umgebaute Neubauer-Studio gewesen sein könnte. Sicher bin ich aber nicht.

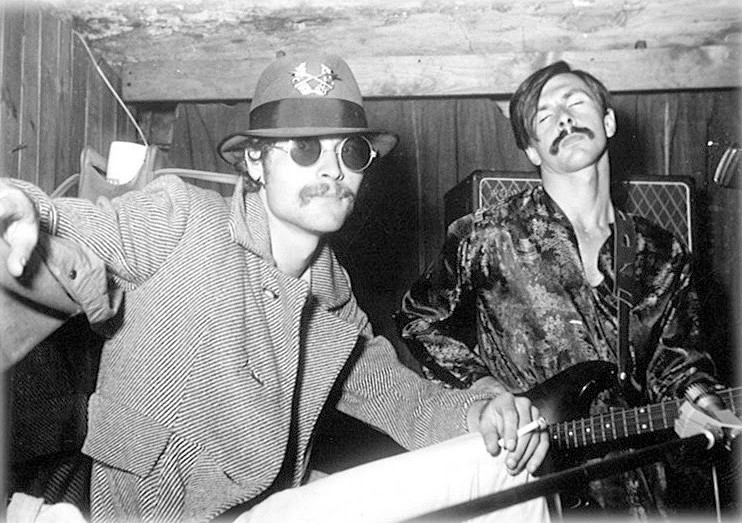

Where did you record the material and what are some of the strongest memories from producing and recording it?

Recorded all material at Neubauer-Studio and my heaviest impression was for sure this big piece of Black Afghan which a fairy godmother had left for us. (I think it was Mister Neubauer himself).

The studio was excellently equipped, comfortable and wide. There was this superb piano Hans-Georg was literally crawling into (‘Edge Of Time’) and this deluxe version of a XXL-vibraphone which I operate on in ‘Dream’. One of the historical feats of Neubauer was to exorcise the last Pink-Floyd-influences by telling us that he doesn’t have an echo console in his Top-Gear-Studio. This was of course a lie, but Neubauer was obviously bugged because we always wanted to have an echo everywhere and in everything.

At that time (just like most of the other ‘Psychedelics’ from Düsseldorf) DOM actually consisted of 99% echo-loops. The most distinctive feature of the Pink-Floydianism was taken away by the ban of Neubauer, so DOM was able to create their unique and inventive sound in the studio. My vocals on ‘Silence’ are the only part were Neubauer accepted echo.

We were forced to drive through half of the city to Eller to get our own one, because he pretended not to have one. How we sounded back then with echo can be heard on the bonus tracks of the CD ‘Flötenmenschen 1-4’.

Wir haben alles Material im Neubauer-Studio aufgenommen. Mein stärkster Eindruck war zweifellos das fette Piece schwarzer Afghane, das uns eine gute Fee (ich glaube, Herr Neubauer himself) da hingelegt hatte. Das Studio war aber auch sonst vorzüglich ausgestattet und kam mir damals ziemlich gewaltig vor. Es war ausladend und gemütlich. Es gab einen hervorragenden Flügel, in den Hans-Georg buchstäblich hineinkroch (“Edge of Time”) und das De-Luxe-Modell eines XXL-Vibraphons, auf dem ich mich bei “Dream” versuchte.

Es gehört zu den historischen Großtaten des Herrn Neubauer uns die letzten offensichtlichen Pink-Floyd-Einflüsse ausgetrieben zu haben, indem er behauptete, in seinem Top-Gear-Studio kein Echo-Gerät zu haben. Das war natürlich eine Lüge, aber eine weise. Neubauer war sichtlich genervt, weil wir immer und überall Echo drin haben wollten. Eigentlich bestand DOM zu der Zeit , ebenso wie die meisten anderen bewusstseinserweiterten Psychedeliker aus Düsseldorf, zu 99% aus Echoschleifen. Durch Neubauers Echo-Verbot war das Haupterkennungsmerkmal des Pink Floydianismus entfernt, und DOM konnte im Studio seinen unverwechselbaren Sound entwickeln.

Die einzige Stelle, in der Neubauer Echo akzeptierte, war bei meinem Gesang bei ‚Silence’. Weil er ja angeblich keines besaß, mussten wir also mitten im teuren Produktionsprozess durch die halbe Stadt nach Eller und uns unser eigenes Gerät holen. Wie wir damals mit Echo klangen, hört man auf den Bonusstücken der CD “Flötenmenschen 1-4”.

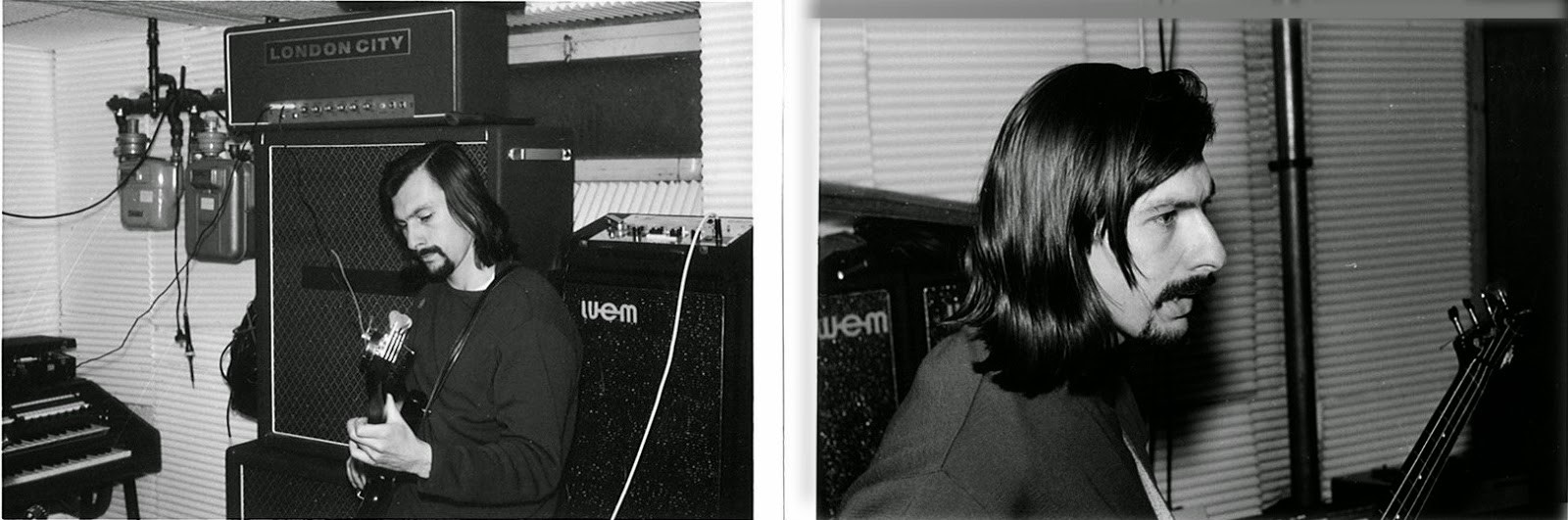

What gear did you use?

We had a WEM (obvious prototype: Pink Floyd) with PA boxes for which Rainer and Hans-Georg had worked during the complete summer on a construction area. I played a Sonor drum set which was replaced by various drums shortly before the recording of ‘Edge Of Time’. Partially an outcome from the influence of the ‘Third Ear Band’.

I also thought it was very sophisticated and comfortable not to have to carry around so much bits and pieces anymore. I was on the peak of my Hippie-Romantic-Period and wanted – young and naïve – to reduce everything artificial and all tools as much as possible.

Paragon was the ‘Third Ear Band’ and The Glass Bead Game by Hermann Hesse, in which the hero (the mighty Glass-Bead-Game-Master) reduced all his technical apparatus to a small flute for children. Synthesizers were new and unaffordable, so the choice for keyboards was mainly

Hammond or Philicorda. We found Hammond too much jazzy, so Hans-Georg played Philicorda with ‘Set Mind’. An instrument with a cheesy plastic-sound, that allowed a reasonable Doors or Soft Machine Keyboard sound. It was a revelation when the Dr. Böhm-Orgel was released as a do-it-yourself-kit. It had a fantastic sound, especially in the sacral register and was affordable.

The rub lies in doing-it-by-yourself.

It took weeks to combine and solder those thousand pieces AND to calibrate it meaningfully.

The result can be heard in all it’s glory in the organ solo of ‘Introitus’.

The absolute killer in Neubauer’s equipment was a Echolette ring modulator with a tonal range which facilitated us to create aggressive, nasty and toxic sounds somewhere between an amputation without anaesthesia and a tilted angle grinder.

Exactly what Hans-Georg – as a fan of Baudelaires “Flowers of Evil” – had dreamed of.

He chops up those lovely flute and guitar landscapes with Neubauer’s infernal machine on the first track of the Lp ‘Introitus’ with appreciative cruelty.

Those 45 seconds of radical electronics are the most painful experience for the highly sensitive listener since their first endodontic treatment. It was very important for us that the Romantic which we just discovered was not drifting into sentimentality or becoming corny.

The roots of the Romantic in the German idealism have been anything but corny and soppy.

Turning away from the civil self was painful, ambivalent and paradoxical.

Represented very clear in the poems of Heine.

Wir hatten eine WEM-Anlage (klares Vorbild: Pink Floyd) mit PA-Boxen, für die Rainer und Hans-Georg den ganzen Sommer auf einer Baustelle gearbeitet hatten. Ich spielte ein Sonor Schlagzeug, das wir aber kurz vor der Aufnahme von “Edge of Time” abgeschafft haben und durch diverse Trommeln ersetzten. Das geht zum Teil bestimmt auf den Einfluss der ‚Third Ear Band’ zurück. Außerdem fand ich es elegant und angenehm, nicht mehr eine Schießbude durch die Gegend schleppen zu müssen. Ich befand mich, damals jung und naiv, gerade auf dem Höhepunkt meiner Hippie-Romantik-Phase und wollte alles künstliche und alle Hilfsmittel so weit wie möglich reduzieren. Vorbild war die “Third Ear Band” und Hermann Hesses “Glasperlenspiel”, wo der Held des Buches, der mächtige Glasperlenspiel-Meister seine ganzen technischen Apparat auf eine kleine Kinderflöte reduzierte.

Synthesizer waren noch neu und unerschwinglich, deshalb beschränkte sich die Auswahl an Keyboards im wesentlichen auf Hammond oder Philicorda. Hammond war uns zu jazzig, deshalb spielte Hans-Georg bei “Set Mind” Philicorda, ein Gerät mit einem käsigen Plastiksound, mit dem man aber immerhin einen ganz passablen Doors- oder Soft Machine Keyboardsound hinbekam.

Als dann die Dr. Böhm-Orgel im Selbstbau-Set erschien, glich das einer Offenbarung. Die hatte einen phantastischen Sound, besonders in den sakralen Registern und war bezahlbar. Der Haken war nur das selber bauen müssen. Es hat Wochen gedauert, die ca. 1000 Teile zusammen zu löten und das Ganze dann noch sinnvoll zu kalibrieren. In seiner ganzen Pracht hört man das Ergebnis beim Orgelsolo auf “Introitus”.

Das brutale Killerteil in Neubauers Gerätepark war ein Echolette Ringmodulator, mit dem man im Klangspektrum einer Beinamputation ohne Betäubung und einer verkanteten Flexmaschine die giftigsten und aggressivsten Sounds hervorbringen konnte. Genau so ein Gerät hatte Hans-Georg als Fan von Baudelaires “Blumen des Bösen” immer schon vorgeschwebt. Auf dem ersten Stück der LP “Introitus” zerhackt er die lieblichen Flöten- und Gitarrenlandschaften in genüsslicher Grausamkeit mit Neubauers Höllenmaschine. Für zart besaitete Hörer zählen diese knapp 45 Sekunden Radikalelektronik zu den schmerzhaftesten Erlebnissen seit ihrer ersten Zahnwurzelbehandlung. Für uns war wichtig, dass die von uns gerade erst neu entdeckte Romantik nicht ins Sentimentale oder Kitschige abdriftete. Die Wurzeln der Romantik im deutschen Idealismus sind ja alles andere als süßlich oder sentimental, sondern als Abschied vom bürgerlichen Ich auch schmerzhaft und ambivalent bis paradox, was man in Heines Gedichten sehr schön sieht.

What can you say about the cover artwork and the related text?

My brother wrote the text, who was the only one in the band that never took acid or smoked weed. He was (and still is) proud of his always-clear physic’s head.

The cover is from his then-girlfriend Jutta Keimer, who (also abstinent) used some physical experiment in which my brother took part as image motif. My brother is particle physicist, so I suppose it shows a bubble chamber. Acid played an important role for the rest of the band.

For Rainer and me in a relatively uninterrupted ‘Hippie-Nature-Romantic’ way….the beauty of silence, speaking sparsely and as truthful as possible. Getting behind the distorted and indoctrinated pictures of society, discard them and focus on the substance.

Hans-Georg was more sort of the clever, urban Hunter-S-Thompson-guy, who swallowed not only Acid but also much heavier stuff, mainly to have fun and to laugh about himself and others.

Der Text ist von meinem Bruder, der der einzige aus der Band war, der kein Acid genommen hatte und auch nie gekifft hat. Er war (und ist) halt stolz auf seinen immer-klaren Physikerkopf. Das Cover war von seiner damaligen (ebenfalls abstinenten) Freundin Jutta Keimer, die als Bildmotiv irgendein physikalisches Experiment, an dem mein Bruder teilnahm, benutzte. Er ist Teilchenphysiker, deshalb nehme ich an, das Bild zeigt eine Blasenkammer.

Für den Rest der Band spielte Acid eine wichtige Rolle und zwar in folgender Rollenverteilung:

Für mich und Rainer in einer relativ ungebrochenen Hippie-Naturromantik. Also Schönheit der Stille, wenig und möglichst wahrhaftig reden. Die gesellschaftlich indoktrinierten Gaukelbilder durchschauen und ablegen und sich auf das wesentliche reduzieren. Hans-Georg war mehr der clevere, urbane Hunter-S.-Thompson-Typ, der alles mögliche, nicht nur Acid, sondern auch weit härtere Sachen, eingeworfen hatte, um Spaß zu haben und sich und andere Leute auszulachen.

Would you share your insight on the albums’ tracks?

“Introitus”

The first song from DOM ever, in which all current and already partially overcome influences interact and work together. Rainer plays the flute and the organ solo of Hans-Georg is a double reverence to the engineering qualities of Dr. Böhm and the keyboard art of Rick Wright. Rainer brought a tape recorder together with a pre-release recording of the LP up to the 4th floor for me to listen to. At that time I was in a private Acid conference together with a friend of mine, floating above a clear Chinese mountain lake. When we reached the ring-modulator interlude I really suffered torturous bodily pain. Full of panic I pushed the stop button and Rainer looked at me, staggered and sad ….. like I had just committed a peerless act of brutality and sawn off the head of our common baby. I did calm down very fast, we listened to the tape until the end and Rainer was cheerful again.

“Silence”

“Silence” is pure Rainer. He sings, plays the flute and has conceived the complete track alone. It contains (at most hinted for the listener, for me clearly evident ) elements of a collective LSD Trip in the “Aaper Wald” in Düsseldorf.

“Edge of Time”

The only track on which I allowed myself to play drums. Too bad. The flute is also mine. Not to mention, how much I hate flutes because of the above mentioned reason. One of my most favourite announcement from my highly adored John Peel goes like this: “I NEVER listen to records that include a flute. Don’t ask me why… but this record from xx (I forgot the name) I really listened to until the end!” The text on Edge of Time is spoken by Hans-Georg and for quite some time it felt like the only real overblown and pathetic element of the record to me. For this reason I often played the record on 45 instead of 33 rpm when I played it for friends in the 1970s. I really suggest everyone who owns the record should try this. It creates a discrete, but (from my point of view) also reasonable second piece.

“Dream”

My favourite track on this record for a long time. Like ‘Silence’ it is strongly shaped by Rainer. The synergy of the guitar and Hans-Georg on the organ is soothing, but without any trace of sentimentality. The ‘Ligeti’ – passages take the subject into a contemporary context in a very unaffected way.

“Introitus”

Das erste Stück von DOM überhaupt, in dem alle damals aktuellen und zum Teil schon überwundene Einflüsse noch einmal nebeneinander stehen. Die Flöte spielt Rainer und Hans-Georgs Orgelsolo ist eine doppelte Reverenz an die Ingeniersqualitäten des Dr. Böhm und die Keyboardkunst von Rick Wright. Rainer schleppte ein Tonbandgerät mit einer Vorabaufnahme der LP zu mir auf die 4 Etage, um sie mir vorzuspielen. Ich befand mich gerade mit einem Freund auf einer privaten Acid-Konferenz und schwebte wie auf Knopfdruck über einem klaren, chinesischen Bergsee. Als dann das Ringmodulator-Zwischenspiel kam, versetzte mich das in körperlich derart qualvolle Schmerzzustände, dass ich panikartig den Aus-Knopf betätigte. Rainer sah mich erstaunt und traurig an, als hätte ich in einem Akt beispielloser Brutalität, unserem gemeinsamen Baby den Kopf abgesägt. Ich beruhigte mich aber schnell wieder, wir hörten das Band zu Ende und Rainer konnte wieder fröhlich blicken.

“Silence”

“Silence” ist purer Rainer. Er singt und spielt Flöte und hat das ganze Stück im Alleingang konzipiert. Es enthält für den Hörer höchstens angedeutete, für mich klar ersichtliche Versatzstücke eines gemeinsamen LSD-Trips im Düsseldorfer “Aaper Wald”.

“Edge of Time”

Das einzige Stück, in dem ich mir gestattete Schlagzeug zu spielen. Schade eigentlich. Die Flöte ist auch von mir. Kaum zu sagen, wie ich Flöten (aus oben genanntem Grund) seitdem hasse. Eine meiner Lieblingsansagen des von mir hoch verehrten John Peel lautete: “Ich pflege NIE Platten zu hören, wo Flöten drauf sind (Fragt mich nicht, warum) aber diese Platte von XY [habe vergessen, wie die Band hieß] habe ich zu Ende gehört.” Den Text von Edge of Time spricht Hans-Georg. Ich habe das eine Zeit lang als das einzig deutlich zu schwülstig, pathetische Element der Platte angesehen. Deshalb habe ich die Platte in den 70ern, wenn ich sie Freunden vorspielte oft auf 45 statt auf 33 rpm abgespielt. Ich empfehle Plattenspielerbesitzern das auch einmal zu probieren. Es entsteht so, wie ich finde, ein eigenständig, durchaus plausibles, zweites Werk.

“Dream”

Seit längerem mein Lieblingsstück auf der Platte. Es ist , wie “Silence” stark von Rainer geprägt. Das Zusammenspiel seiner Gitarre mit Hans-Georgs Orgel empfinde ich als höchst besänftigend, ohne jede Spur von Sentimentalität. Die “Ligeti”-Passagen klammern das Thema auf ungekünstelte Weise in einen zeitgenössischen Kontext ein.

“One whole day on great LSD should be enough for life, or?”

What’s the story behind your band name?

My original idea in the summer of 1970 was “D-OM” which should have signified a (more or less trashy) conjunction between western and eastern mysticism. The omission of the hyphens was an aesthetic decision and should not – like some still believe – be a reference to the super drug DOM, which was circulating in those days. DOM was a very strong LSD that took you on a trip for days, but neither of us tried it. As far as I know not even Hans-Georg.

I mean…one whole day on great LSD should be enough for life, or?

Meine ursprüngliche Idee im Sommer 1970 war “D-OM”, was eine, wie ich heute finde, etwas kitschige Verbindung von westlicher mit östlicher Mystik andeuten sollte. Das Weglassen des Bindestrichs war eine ästhetische Entscheidung und sollte nicht, wie manche glauben, auf die damals kursierende Superdroge DOM anspielen. DOM war ein sehr starkes LSD, das einen tagelang auf Trip brachte, das aber keiner von uns probiert hatte, nicht mal Hans-Georg, soweit ich weiß. Ich meine, ein ganzer Tag auf gutem LSD reicht doch wohl fürs Leben!?

Who were some of the artists you shared the stage with?

We mostly played in Düsseldorf and Aachen. The highlights in Düsseldorf have been the Kunsthalle, the Creamcheese and the Big Ape, a sophisticated hippie club in the Königsallee.

From Aachen, where my brother studied physics, I recall the Neue Galerie, the Audimax and the Malteserkeller. We played as support for the Spencer Davis Group at the Audimax (strange mixture), at the Creamcheese I once called my friend Frank Köllges on stage to join us on the percussion without having ever rehearsed at all together. But that wasn’t necessary with Frank, who started some very innovative stuff later on together with Padlt Noidlt and others.

Wir spielten hauptsächlich in Düsseldorf und Aachen. Highlights waren in Düsseldorf die Kunsthalle, das Creamcheese und das Big Ape, ein mondäner Hippieclub in der Königsallee. In Aachen (mein Bruder studierte da Physik) erinnere ich mich an die Neue Galerie, das Audimax und den Malteserkeller.

Im Audimax waren wir der Support der Spencer Davis Group (eine merkwürdige Mischung), im Creamcheese holte ich meinen damaligen Freund Frank Köllges als Percussionisten auf die Bühne, ohne jemals vorher zusammen geprobt zu haben. Das war bei Frank aber auch nicht nötig, der ja später mit Padlt Noidlt u.a. höchst innovatives auf die Beine gestellt hat.

How did critics receive the album? Did it break in any markets?

I really can’t remember. The lion’s share was private distribution, but that was mainly organized by my brother and Hans-Georg. I’m sure there were some local critics, but I can’t remember when or where they were published.

Ich weiß es nicht mehr wirklich. Der Hauptanteil war Eigenvertrieb, mit dem ich aber nichts zu tun hatte, weil mein Bruder und Hans-Georg das organisiert hatten. Kritiken gab es einige regionale, ich erinnere mich aber nicht mehr wann und wo.

What happened after the album was released?

Well, we disbanded shortly after the LP was released.

My brother had to stay in Genf at the CERN more often and much longer, Hans-Georg wanted to get further with his medical study in Frankfurt and I desperately wanted to go to India to get rid of my EGO.

Wir haben uns sehr zeitnah zur Veröffentlichung der LP aufgelöst. Mein Bruder musste / blieb immer länger in Genf beim CERN, Hans-Georg musste mit seinem Medizinstudium in Frankfurt weiterkommen und ich wollte unbedingt nach Indien, um mein Ego loszuwerden.

What did you do after 1972?

Well, I didn’t reach India because I couldn’t get a visa with my Hungarian refugee passport.

So I decided to pretend a ‘civil existence’ to get a German passport by starting a cross flute studies in Aachen. Musically a big mistake, because my Romantic episode had already begun to recede and to evolve in the Dadaistic Pre-Punk direction. If I had studied drums at that time, which I did not hate that much and could play much better than the cross flute, I would probably play music as main job nowadays. After the cross flute I did German studies and Art studies, invented a small print product directly after finishing, which I continue to conduct as a culture-and-satire magazine up to today. From the early 1980’s to 2007 I had this wild-improvised-Post-Punk band called “Die Malangrés” in Aachen, where I still live today. It was part of the concept of unrepeatability, that we did not release any recordings and pushed all energy into the live gigs.

Hans-Georg and Rainer continued as a duo for a short time, but more or less faltering, without big ambitions. Both died very early at the beginning of the 1990’s.

My brother Laszlo is a nuclear physicist and works as a professor in the USA since the 1980s.

First in Boston, than Dallas, now Florida.

Bei mir hat Indien nicht geklappt, weil ich mit meinem ungarischen Flüchtlingspass kein Visum bekam. Um einen deutschen Pass zu bekommen, entschloss ich mich, eine bürgerliche Existenz vorzutäuschen, in dem ich in Aachen begann Querflöte zu studieren. Musikalisch ein Fehler, weil da meine Romantikphase bereits anfing abzuebben und sich in die dadaistische Prä-Punk-Richtung weiterzuentwickeln. Hätte ich damals Schlagzeug studiert, was ich viel besser konnte und das ich nicht so gehasst habe, wie sehr bald die Querflöte, würde ich wahrscheinlich heute noch hauptberuflich Musik machen.

Ich habe dann Germanistik und Kunst studiert und direkt nach dem Studium ein kleines Printprodukt entwickelt, das ich als Kultur- und Satiremagazin bis heute betreibe.

Anfang der 80er hatte ich in Aachen, wo ich seitdem lebe, eine wild improvisierende Post-Punk-Band namens, “Die Malangrés” mit der wir bis 2007 krachig improvisierte Musik im Aachener Raum gemacht haben. Es gehörte zum Konzept der Unwiederholbarkeit, keine Tonträger zu veröffentlichen, sondern alle Energie ins Live-Spielen zu legen.

Hans-Georg und Rainer haben noch eine Zeit lang zu zweit weitergemacht aber ich glaube, relativ halbherzig, ohne großen Einsatz.

Beide sind sehr früh, Anfang der 90er Jahre gestorben.

Mein Bruder Laszló ist Kernphysiker und arbeitet seit den 80er Jahren als Professor in den USA. Erst in Boston, dann in Dallas, jetzt in Florida.

What currently occupies your life?

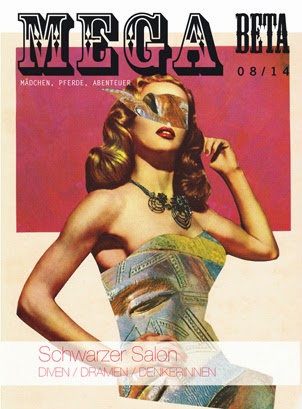

I continue to work on the zine “Moviebeta”, that I maintain on the internet together with various film projects, for which I also recorded the music. At the moment we are preparing a new website, which is conceptualized as a satiric – Dadaistic, zine-supporting master plan.

Ich mache meine Zeitung “Moviebeta” weiter, die ich mit diversen Filmprojekten, zu denen ich auch die Musik mache, im Internet begleite. Wir arbeiten gerade an einer neuen Website, die Anfang Januar fertig sein soll, und als magazinbegleitendes satirisch-, dadaistisches Gesamtkonzept konzipiert ist.

Any chance you’ll get back together?

At the utmost once: “In the Night Of The Living Dead”.

Höchsten einmal noch: “In the Night of the living Dead”.

Would you like to send message to It’s Psychedelic Baby readers and your fans worldwide?

“Two dimensions are one too many.”

“Zwei Dimensionen sind eine Dimension zu viel.”

– Klemen Breznikar

(Translation to German by Patrick Helfrich)

Just came across this, and what a great read it was! "Edge of Time" is one of my all-time favourite albums and I never thought I'd see an interview with one of the original band members. Even though I know the album musically inside out, it has always been shrouded in mystery. This is probably a good thing as it adds to the mystique, but I've always wanted to know more. Now I got the chance. 😀

Thanks a million for this interview!

nice post

Incredible read. This album is one of the most unique and mystic one's of the period. Been trying to find the original LP for a long time, and was sold a counterfeit for 300 Euros. Watch out for that.. The original only has a single matrix nr. and the vinyl is supposed to be a bit thicker too. Thanks for uploading this and doing this amazing interview. Reine Fiske

"Edge of Time" is a MASTERPIECE. My favorite psychedelic record of all time.

Thank you IPB Magazine for a fantastic interview. Not at all the typical ex-rock-casualty stuff:

Gabor seems super-intelligent and very insightful. Gabor you are BEAUTIFUL, thank you for the

beautiful music !!!