Fred Frith interview about Henry Cow & beyond

Thank you very much for taking your time and effort, Fred! Please tell me where did you grew up? What were some of the main influences?

I grew up in Yorkshire, first in a sleepy market town called Richmond, ad later in the city of York. I spent a lot of time in the countryside, playing games, fishing and bird-watching, walking in the hills. At the time the UK was more London-centric culturally speaking even than now, so I had very little exposure to anything. I was principally influenced by my family, who loved music and had very different tastes, so I could be listening to Delius or Debussy one day, and Django Reinhardt and Humphrey Littleton another, and Johnny Ray and Paul Anka the next. I also had a wonderful music teacher until I was about 12, Rodney Mayes, who gave me warm encouragement in all my endeavors, which at the time were principally playing the violin (rather badly!) When I went to boarding school in Cambridge I was closer to London and it was also a more cosmopolitan university environment, so there was more to see and hear, but I can’t say I really went out much until I became an undergrad in 1967. However, at school I DID meet a Yugoslavian called Bojan Jovanovic, and he introduced me to some traditional Balkan folk music. We were in a blues band together, but we used to throw in some of his tunes. That was an experience that stayed with me afterwards.

In what way did it influence?

Well, I liked the challenge of playing in something other than 4/4, for one thing! I’d only heard that done by Dave Brubeck, who was hugely popular at the time, but this music spoke to me more directly, and it gave me a challenge. Plus Bojan was a character, so there was his slightly out of control, crazy aspect to it as well…

Your first band was “The Chaperones”. At first you were pleased with Beatles and Shadows covers but then you also started playing more bluesy oriented tunes. How do you remember those days?

We started out doing Shadows covers, but we never actually performed any Beatles songs, I think it was beyond our capacity, especially since we had very little and very poor equipment, not having any money! We would sing that stuff for fun but never on stage. My big brother gave me an Alexis Korner record meanwhile, and then there was Bob Dylan and eventually I heard Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf and then we started playing that material instead.

At Cambridge University you got to know Tim Hodgkinson, a fellow student. How do you remember some of the early sessions you had together? Your first gig was with Pink Floyd, back in the 1968, right?

Tim and I met in the local blues club and hit it off. He introduced me to some music I didn’t know, notably Charles Mingus and Ornette Coleman, and not long after we met we were invited to play with a dancer, Francis Bacon, and we kind of discovered free improvisation by the act of doing it. It was pretty intense—a big door opened up. So we started a band with the idea of doing some kind of “altered” blues, but a lot of what was happening was pretty spontaneous – long, drony jams that would have probably sounded quite contemporary if you heard them now, and our own songs interspersed with Coltrane covers and traditional material. We opened for the Pink Floyd a few times back then, since they were also a Cambridge band and liked to play local gigs. After Syd quit the Floyd I also played very briefly in a band with him, with Jack Monck and Twink. Jack was kind of the king of the Cambridge underground music scene, and he was trying to help Syd out, but it didn’t get very far, and I only lasted one gig, though they soldiered on for a bit longer!

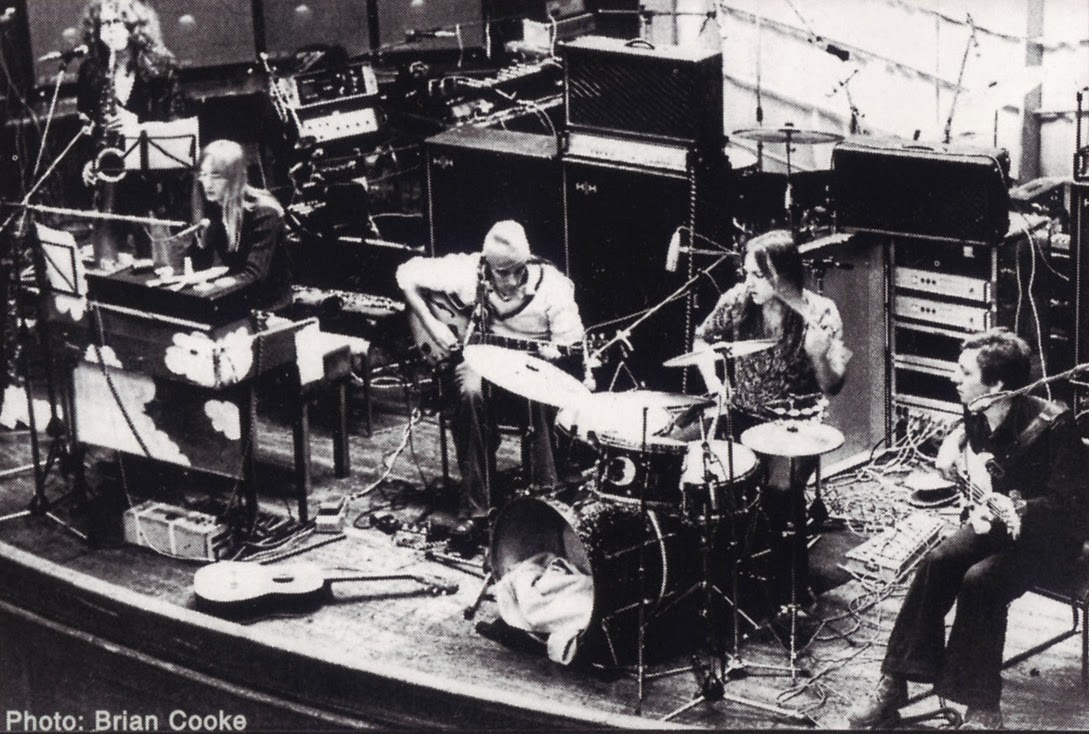

How did you got the name Henry Cow?No idea.You played a lot of shows and line-up changed a few times before you settled down and recorded your first Henry Cow LP. What can you remember from some of the shows you had before recording the LP? How did the audience react to your music?

You’re talking about a period of five years, which is a hell of a long time, so it’s really impossible to encapsulate it simply. We just tried to keep on learning and keep on getting better, like any other young musicians. We developed a small but dedicated following. When Chris joined it all finally started to make sense, though it was never easy, and we worked incredibly hard.

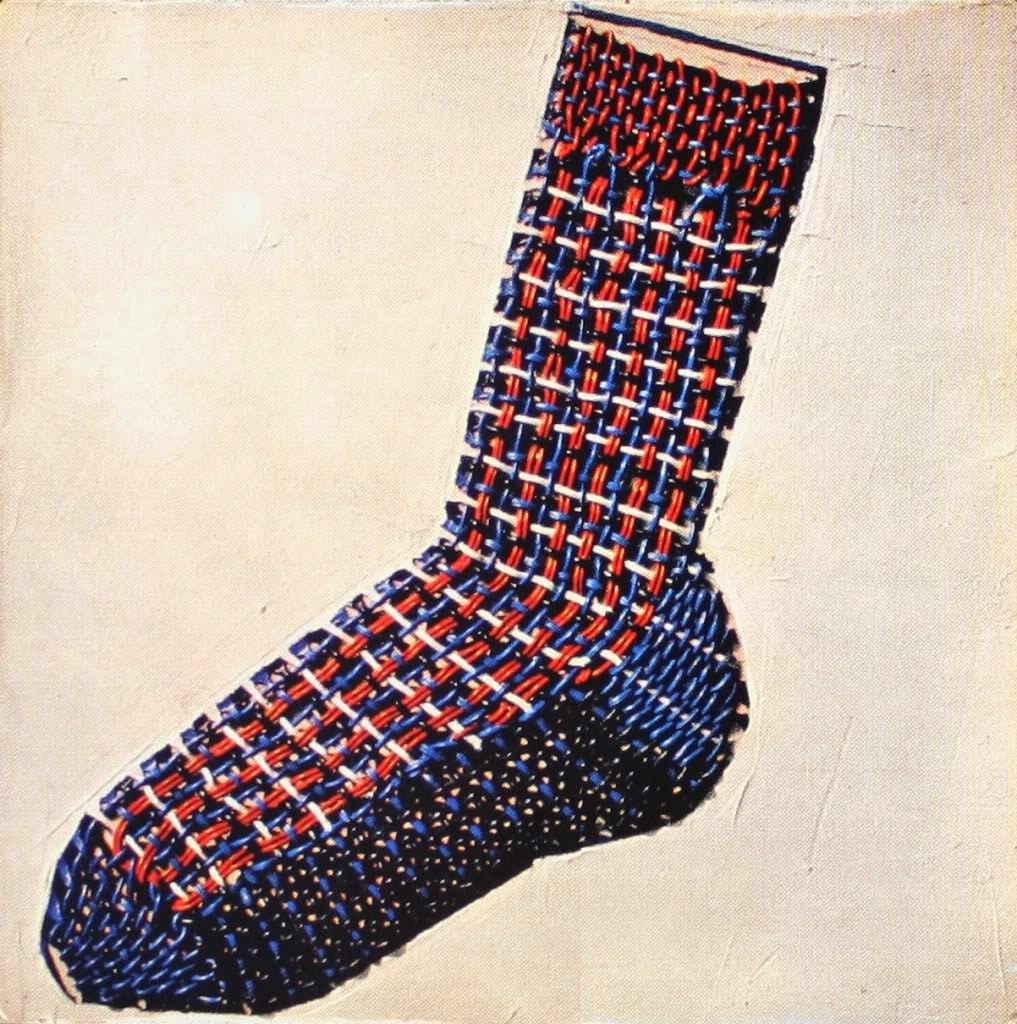

Around 1972 you finally got a contract with Virgin Records and you recorded “Leg End”. What are some of the strongest memories from recording your first LP?

My strongest memory is of falling in love with the recording studio. It was bliss. It’s still where I most like to be! Other than that we were blessed with a wonderful engineer, Tom Newman, who left us to our own devices, showed us how everything worked, and made us laugh (a lot) which was important when under all the pressure to make a great first record with zero experience of recording and a lot of the usual creative tensions. Leg End was really a summing up of everything we’d done up until then, and from that point of view it was almost as if we could finally get rid of a lot of stuff and make a new start.

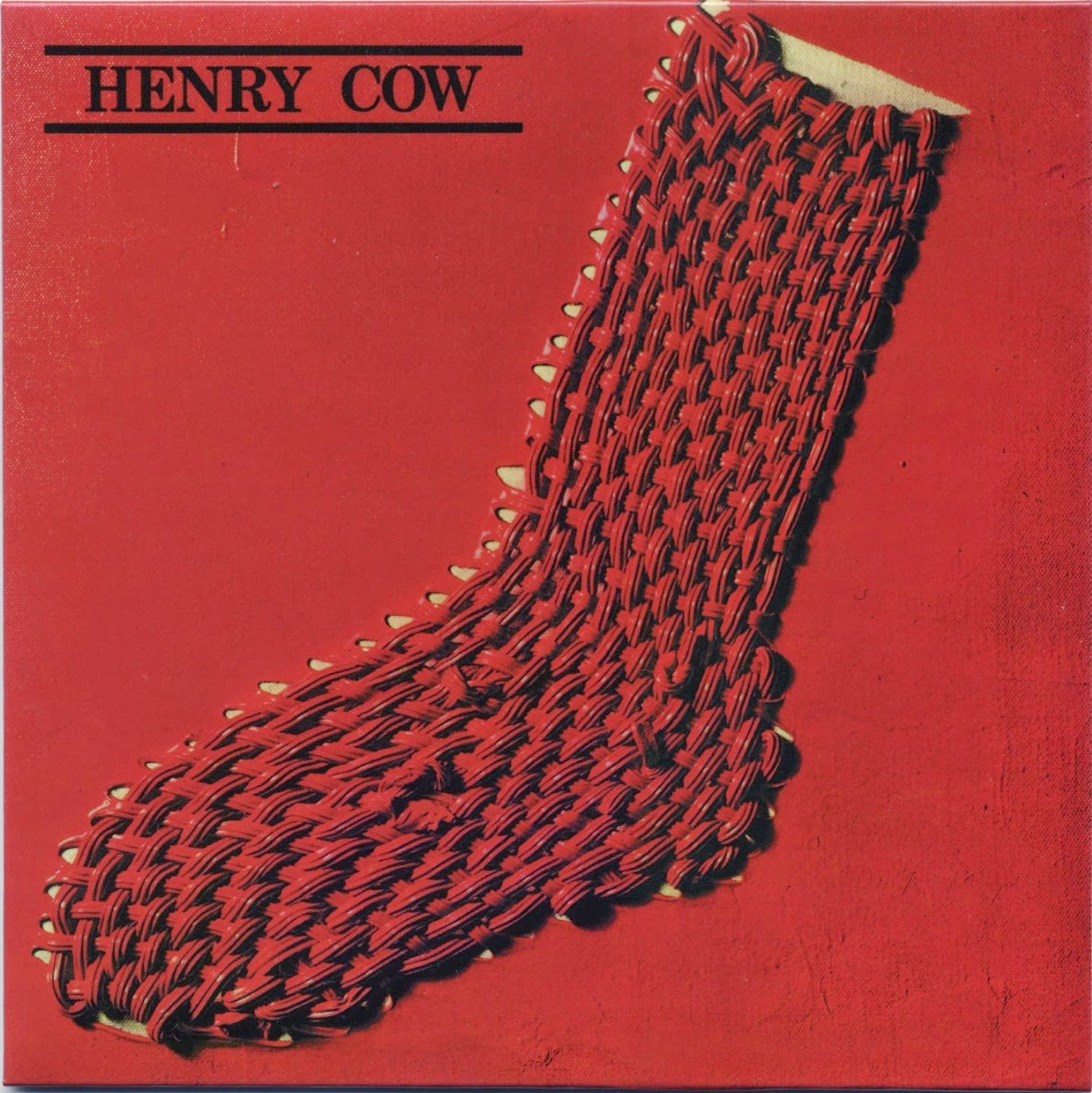

In 1974 you released “Unrest” and a year later “In Praise of Learning”. Would you like to share a few memories from producing and recording these two LP’s?

Making Unrest was a wonderful and radical experience, colored by a lot of personal shit going on that weighed heavily on the whole thing, at least for me. But it set the tone for everything I’ve done in the studio since, giving us a deep understanding of the possibilities of the medium, and producing some extraordinary results like Deluge, which still sounds completely fresh to me. In Praise of Learning was different because we were dealing with a different kind of technology (dbx instead of Dolby noise reduction). I personally hated the sound of it, plus we were working with the newly merged members of Slapp Happy, who were clearly less than enthused by our way of discussing every idea to death. So it was less fun and a lot more cooks in the control room—I mostly remember it as kind of weirdly dysfunctional, but I don’t remember much about it at all, actually, maybe because I don’t want to!

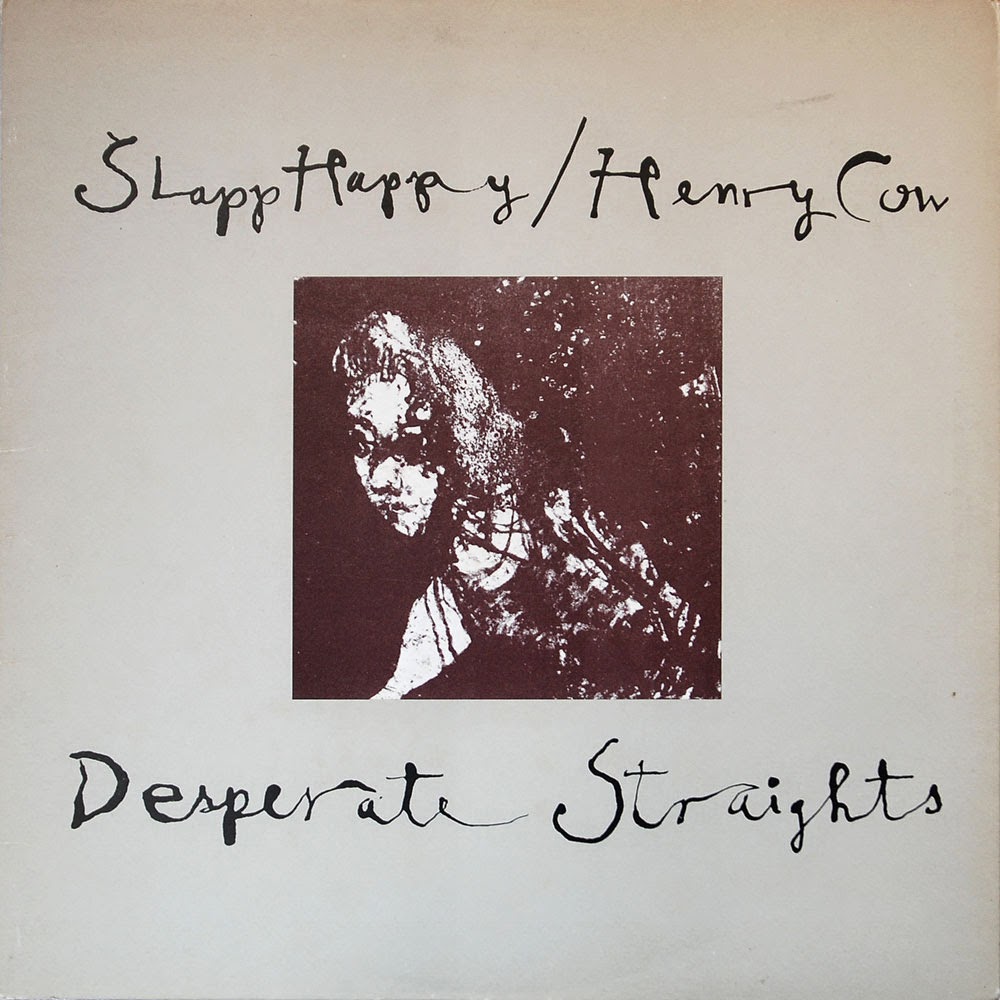

We met them because we were both signed to Virgin, and we loved their first LP. I think we found each other oddly fascinating, given how different we were in every way. Making Desperate Straights was a blast, and allowed Henry Cow to explore ways of dealing with songs, which was close to my heart. And it re-wakened a strong interest in working with lyrics and a singer, which we’d kind of abandoned at that time. Dagmar became our muse, and we wrote for her extraordinary voice and mesmerizing stage presence. It changed us. Slapp Happy must have had mixed feelings about it, to say the least.

You toured with Faust, organized by Virgin Records and a bit later with Captain Beefheart. Did you get along with them backstage?

We got along well with Faust. In fact I even manned the road drill on stage with them a couple of times. And they were eccentric and radical, and serious rock improvisers in a way that impacted me greatly. Beefheart was sadder. He was working without the Magic Band for the first time, and though his musicians were perfectly good, there clearly wasn’t the chemistry, and he was personally pretty unhappy. We hung out a bit on the road, in fact I stayed in touch with him for several years after that tour as it turned out, though not in the latter years I’m sorry to say.

In 1974 you also released your first solo album “Guitar Solos”. What was the concept behind it?

I gave a copy of that record to Beefheart, and years later John French told me that Don had handed it on to him and said: “check this out – he’s ripping me off!” Which was certainly true of the title of No Birds! Anyway, the concept was to try and reinvent the guitar the same way that John Cage had reinvented the piano or Barre Phillips had reinvented the bass – to transform and expand its expressive potential. That’s it really. And of course I was coming from a primarily rock and folk background, so, while it may be experimental, it still stays pretty close to its roots. I wasn’t part of the London improvised music scene at that time, my only connection to it came through Lol Coxhill, who I’d started playing and hanging out with in the early 70s.

In March 1978 Henry Cow invited four European groups, Stormy Six (Italy), Samla Mammas Manna (Sweden), Univers Zero (Belgium) and Etron Fou Leloublan (France) to come to London and perform in a festival Henry Cow had organized called “Rock in Opposition”.

To be honest I had very little to do with it. It was Nick Hobbs and Chris Cutler’s baby, and although I knew these musicians, and some—Lasse Hollmer, Marc Hollander, Ferdinand and Guigou—became good friends, I was not particularly connected with the Rock in Opposition “label” other than as a member of Henry Cow. I never thought it was a very coherent idea, and certainly never considered RIO to be a “genre”. Still don’t. The ties that bound a lot of these groups seemed pretty tenuous to me at the time. I mean, it was fun to hang out and all that but I didn’t really get it. And I didn’t attend any “meeting” of the groups. Sorry. What Rock in Opposition has become now, is something entirely different, and I’m still not at all sure what it signifies, but I can see that people are very passionate about it!

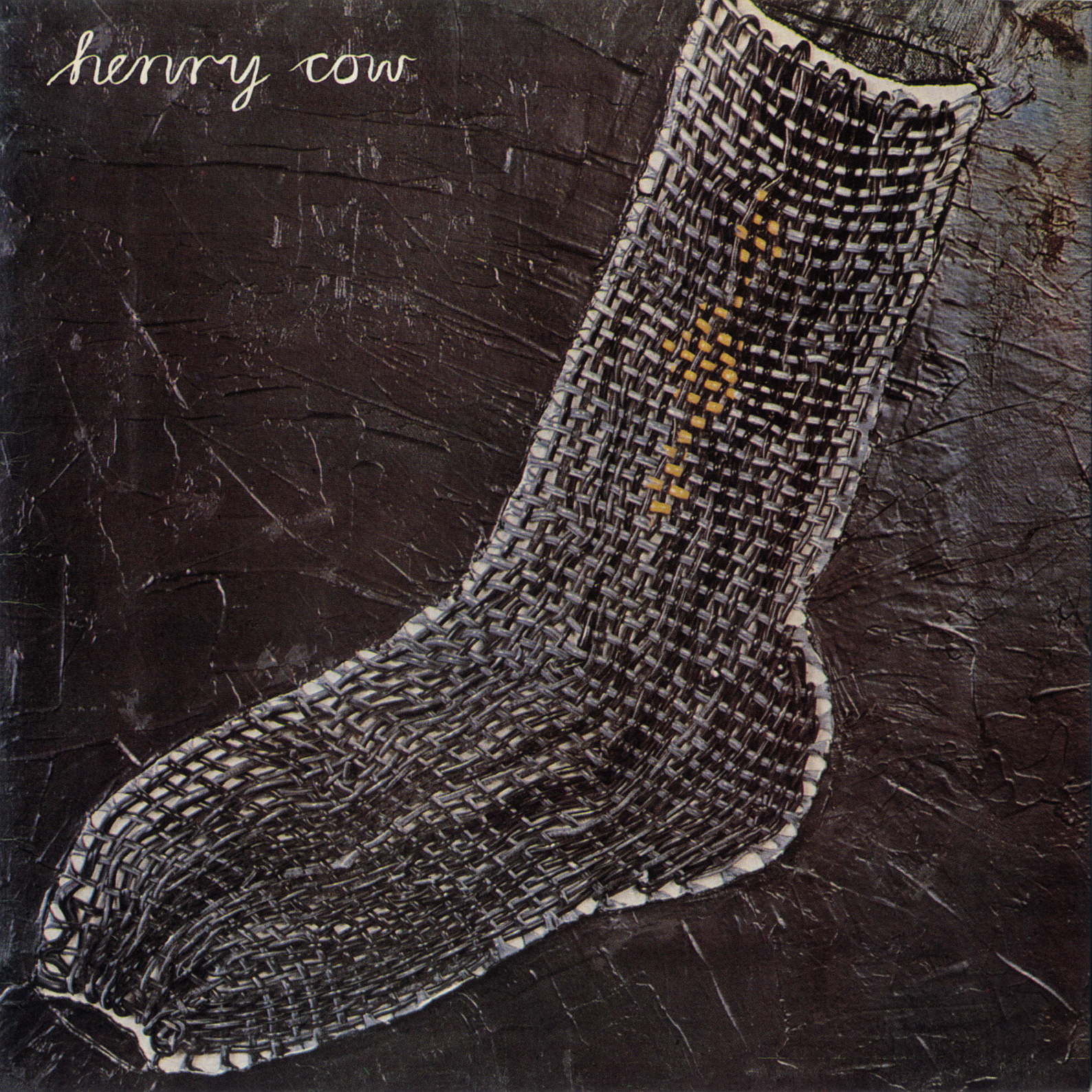

“Western Culture” & Art Bears followed.

We had hired Dagmar, who was no longer a member of Henry Cow, to come and record a major work of Tim’s. While we were preparing the piece there was an intense discussion about lyrics, which led to our deciding to postpone the recording and do it later. But since the studio was booked and Dagmar was coming, we thought it would be productive to make use of the time to record some songs. So Chris and I (primarily) went to work at very short notice to create the material – Chris providing words, and me the music. (Actually Tim wrote the very beautiful Pirate Song, which is my favorite on the album, but that’s another story!) Anyway, we recorded what we’d done, and it was clear that some of the group didn’t feel the material was worthy of a Henry Cow release. So Chris and Dagmar and I proposed that we release it under another name, with some additional material, and that we make another record later with material by Chris and Lindsay, which we did – that was Western Culture.

Around 1979 you moved to New York. How was the scene?

Goodness, where to begin? There are times when you just happen to be in the right place at the right time, and that was me in New York in October 1978. Henry Cow had broken up and I was feeling a bit lost. I had a call from Giorgio Gomelsky inviting me to come to New York (and paying my ticket). I had nothing to lose and was at a moment in my life where I was completely open. When I reached his loft, directly from the airport, I met Bill Laswell and Fred Maher and Michael Beinhorn, who were rehearsing a tune of mine in the basement. It was a great way to arrive! Over the next couple of days, at the Zu Manifestival and elsewhere, I met all kinds of people—The Residents, and The Muffins, whose work I knew and admired, and some whose names were new to me (Glenn Branca, Rhys Chatham). I also fell in love with Tina Curran, and six months later we were married, and I’d hooked up with Zorn, Tom Cora, Kramer, Lesli Dalaba, Bob Ostertag and countless others. It wasn’t that the scene was “bigger for my type of music”. More that there was something else going on that I wanted to be part of, and “my type of music” was forced to develop in new and unexpected ways, which is how it should be, right? I would say that 1977 to 1984 was a key era in New York when walls were loosening, and I feel lucky to have been a part of it.

Later you formed many very interesting projects like Massacre, Skeleton Crew, Keep the Dog etc. You also recorded a few solo albums, starting with “Gravity”. You also began writing music for dance, film and theatre. Your life changed a lot.

Absolutely. To give you a sense of how much creative energy it unleashed, between 1978 and 1984 I was involved in making:

Henry Cow: Western Culture

Art Bears (Hopes and Fears, Winter Songs and The World As It Is Today)

Aksak Maboul: Un Peu de l’Ame des Bandits

Gravity: Speechless and Cheap at Half the Price

Massacre: Killing Time

Material: Memory Serves

Skeleton Crew: Learn to Talk

With Friends Like These and Who Need Enemies (with Henry Kaiser)

Voice of America (with Bob Ostertag and Phil Minton)

French Gigs (with Lol Coxhill)

Rags (Lindsay Cooper)

The English Channel (Eugene Chadbourne)

Commercial Album (The Residents)

The Big Gundown (John Zorn)

The Golden Palominos (w. Anton Fier & Arto Lindsay)

Live in Prague and Washington (with Chris Cutler) That’s more than 20 fucking awesome records in six years, if I say so myself, and the list doesn’t include the ones I guested on or produced, and none of it bears much resemblance to anything I’d done before. I’m not surprised my marriage didn’t last, I was working myself to exhaustion…

Later you joined John Zorn’s Naked City.

Intense. Trying to keep up with these geniuses while playing my second instrument. I learned a huge amount just from watching Frisell night after night. And we didn’t play any gig during our whole existence where we didn’t perform at least one new song, so we never stopped working. Exhilarating I would call it. Exhausting as well, yes.

What can you tell me about the documentary that was released in 1990?

Step Across the Border was another life-changing experience. The act of being filmed was kind of like shedding a skin, it enabled me to reinvent myself afterwards, because that version of me is always available now! It’s a great movie, though I had to get used to that version of me on the screen, and I didn’t much like it at the beginning. Now it’s OK, it’s just some other guy up there! Nico and Werner are poets, and they weren’t making a “documentary”, they were exploring the idea of improvisation, and that’s why the film is so successful – it goes deeply into its subject matter. We spent a wonderful year together and it changed all of us. We will always have that special connection. It’s still being screened, and I’m still invited to talk about it.

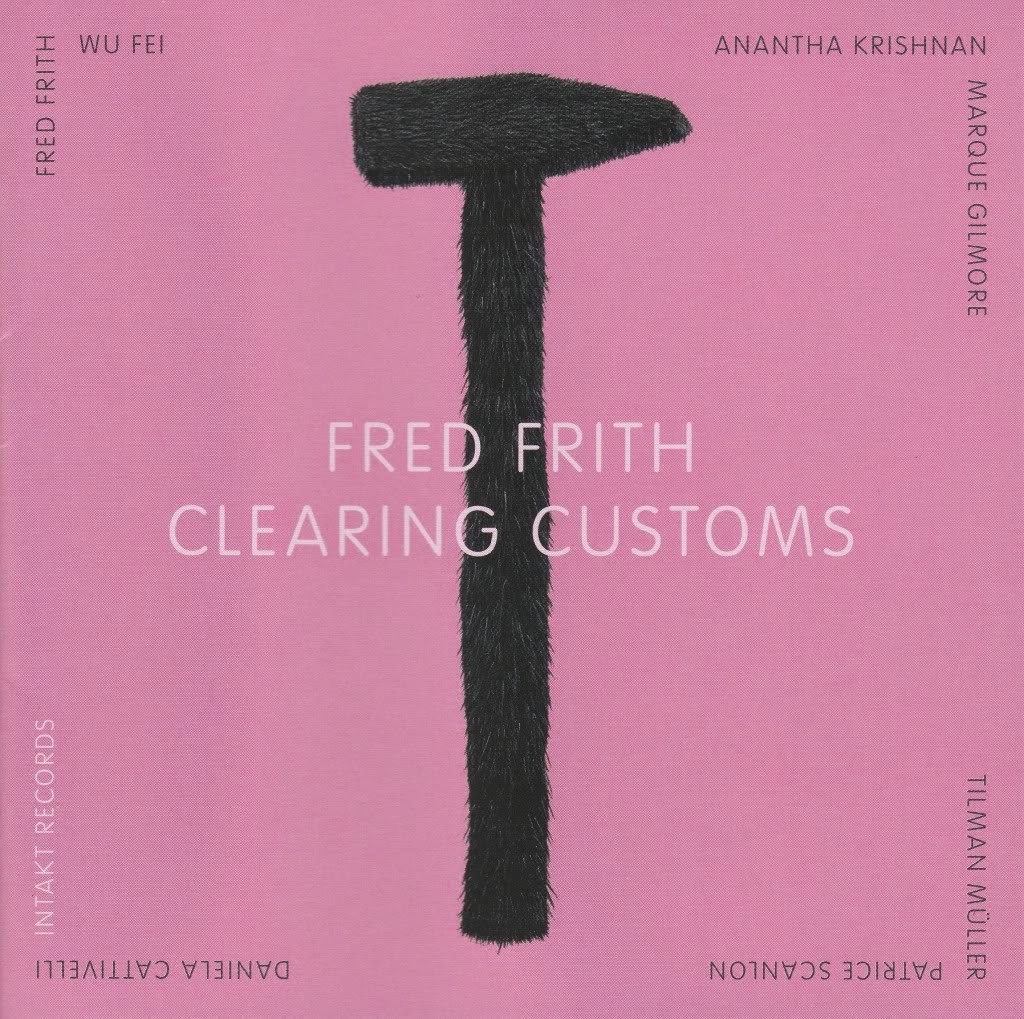

Your recently released “Clearing Customs”. Would you like to present it to our readers?

That’s a big jump, from 1989 to 2010. I did quite a lot in between! But Clearing Customs was a project that I undertook within the framework of something called New Jazz Meeting, which was started in the 60s by SWR (German radio) and proposed a meeting between American and European improvisers, which at that time meant jazz players. Now it’s much broader, and involves electronic musicians as well, but a key aspect is that the players are meeting for the first time. I had the idea to experiment in the way Peter Brook did with actors, and invite players from different cultural backgrounds to meet for the first time and try to forge an understanding. It was a fantastic experience. The expression “clearing customs” had multiple meanings for me – “crossing borders”, of course, but also “getting rid of old habits”, and also ”the things you do when you have space around you”. It was playful and deep at the same time, and those musicians were and are amazing—Marque Gilmore, Anantha Krishnan, Wu Fei, Tilman Müller, Daniella Cattivelli, Patrice Scanlon. That’s a hell of a band!

What else are you involved with at the moment and what are some of the future plans for you, Fred?

I’m very involved in teaching – at Mills College in Oakland, and also at the Musik Akademie in Basel, Switzerland. I’m helping to run Master’s programs in Improvisation at both of those institutions. Other than that I’m composing a lot, for film but also at the moment for the Paul Dresher Ensemble. And I’m about to finish mixing Cosa Brava’s new CD, which is called The Letter. We’ll be touring in Europe in May, and I’m very excited about that.

Thank you very much for this interview! Would you like to send a message to It’s Psychedelic Baby readers?

My pleasure. My message to your readers is “Occupy!”

– Klemen Breznikar

- Front.jpg)

Fucking Excellent.

Just a great piece to read to start the new year.

Thank you for this enjoyable interview. Love Fred's work, nice to hear some details on his perspective.

Good post.🙂