The Musical Players – The Chemist, The Preacher And The Musical Players: The British Acid-Folk Album That Almost No One Heard

Originally pressed in 1972 in an edition of around ten copies, ‘The Chemist’ by The Musical Players sits comfortably among the rarest and strangest artefacts of British acid-folk.

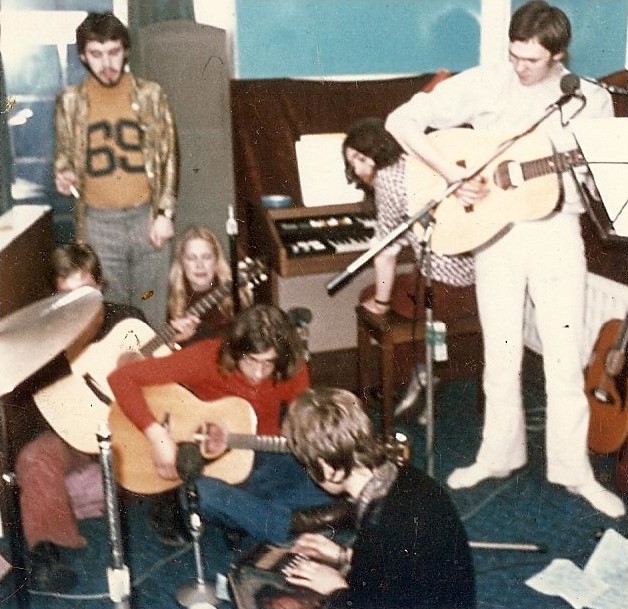

There was no master plan, no scene manoeuvring, just “a group of friends, with varying degrees of musical ability, who came together from time to time to jam and sometimes to record songs.” That looseness is the key to the record’s peculiar power.

The Musical Players were a fluid collective gathered by Keith Ripley and Keith Washington, operating out of West Yorkshire at a time when “beat groups,” soul clubs, arts labs, and countryside LSD sessions overlapped freely. The album’s title makes its allegiances plain, referencing Timothy Leary and Augustus Owsley Stanley III, but this was never a sermon. “I don’t think we were consciously trying to proselytise through our music,” Washington recalls, even as the band drifted through acoustic guitars, sitar, violin, hand percussion, and the occasional electric surge.

Recorded more or less live at Northern Broadcast Recording Studio near Huddersfield, with minimal rehearsal, much of ‘The Chemist’ was “improvised in the studio.” Influences like the Incredible String Band and Tyrannosaurus Rex are audible, but the mood is darker, earthier. Woodland rites, fuzz-stained visions, ley lines and windowpane acid, a rural English counter-culture caught on tape at harvest time.

Would you mind discussing your childhood and formative years? Where exactly did you grow up, and what was that time and place like?

Keith Washington: I grew up in Halifax, a smallish industrial town in West Yorkshire in the north of England. My teenage years coincided almost exactly with the recording career of The Beatles, so they played a major part in developing my musical sensibilities. I got my first real guitar at age 13 and formed my first group with a bunch of school friends not long after. We played covers of Beatles and Stones songs, plus some of the standard sixties material that influenced them, Chuck Berry, early Motown, some blues, and did a few local gigs. There was quite a thriving live music scene, with lots of “beat groups”, as they were called back then, and besides the local groups I got to see some big-name acts like The Everly Brothers, The Kinks, Them (post–Van Morrison unfortunately), The Moody Blues, Dusty Springfield and many more.

In my later teenage years, a group of us, including many of the people who played on ‘The Chemist,’ used to frequent a particular club in Halifax called The Plebians, which had originally been a jazz club but now played mainly soul, blues and Motown, including some live acts. Then, in the months before I went off to university in London at 18, an Arts Lab was set up in Halifax where you could get involved in some avant-garde, experimental stuff, not just music but film, theatre, poetry, dance, etc., so that expanded my artistic horizons somewhat.

By 1972, there were fewer live music venues locally, though there was a club called Clarence’s where reasonably big-name acts sometimes appeared. Living in London, I had access to most of what was going on at the time when funds permitted. Those I remember seeing perform include Pink Floyd, Free, Deep Purple, The Faces, The Who, Third Ear Band, Joe Cocker, Genesis, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Tyrannosaurus Rex, Leonard Cohen, The Incredible String Band, Joni Mitchell, Fleetwood Mac, Led Zeppelin, David Bowie and Roxy Music.

Keith Ripley: I was born in Halifax in 1950, moved to Sheffield in ’56, and then back to Halifax in ’61. My mum and dad were working-class and ran a newsagency on the edge of town – we lived above the shop. There weren’t many children around in that area, so school provided friendships. As my parents couldn’t shut the shop, I spent a lot of holiday time with my paternal grandparents – a very loving relationship

Moving on to the other members of The Musical Players, what can you tell us about them?

Keith Washington: Keith Ripley I would say was the driving force behind this recording. He’s good at organising people and getting them involved, and at that time he was probably more in contact with the others than I was. Also, his parents owned a newsagent’s shop near the centre of town with a basement where we used to rehearse in The Institute, so we would often gather there, especially on Sundays when his parents would go to their caravan in the Yorkshire Dales.

Brian was a great drummer, and later on played with a couple of bands in London, but I don’t think he did much of the drumming on this record, maybe because he wasn’t available much to rehearse the songs (though to be honest I don’t remember there being many rehearsals!), or maybe it was just that Paul Simon was providing the drum kit. Brian was a good singer too, and it’s his voice on my song New Kind of Life, with his cousin John Robertson playing guitar.

Philip McNally played bass on most of the tracks and provided some backing vocals. Both Keith Ripley and I have recorded with him several times subsequently, together and individually. He moved to Devon in later life so we don’t see much of him these days, but I think he still plays.

Paul Simon moved to London a couple of years after this recording and has been involved in various musical ventures over the years. His younger brother Robert (later Robin), who didn’t play on The Chemist but did contribute to two later recordings we did, was the guitarist in the band Ultravox for a while.

Col Innes and Stefan Sotnyk were our contemporaries at school and we still maintain regular contact, though Col has lived in California since 1979. They both contributed some additional instrumentation and, in Col’s case, percussion.

Keith Coleman was another of our school friends. He’s a poet and became quite well-known as a writer of haiku. I think he was there mainly because he wrote the words to ‘Adult Tree Ballad’. A few years later he formed an acid-jazz group with Phil Hartley, who wasn’t on the record but came up with the album title.

Meryl Priestley was Keith Ripley’s girlfriend at the time, and later my wife. One of her close friends was Helen Williams who played the violin, as did her mother Doreen, a music teacher, so Keith enlisted their services as a string section along with Janet Austin, who’d also been at school with us though she was a few years younger. Meryl’s brother Gareth also came along to play guitar on one or two tracks.

Keith Ripley: They were all friends from school.

Were you, or any other members of The Musical Players, involved in any bands prior to its formation?

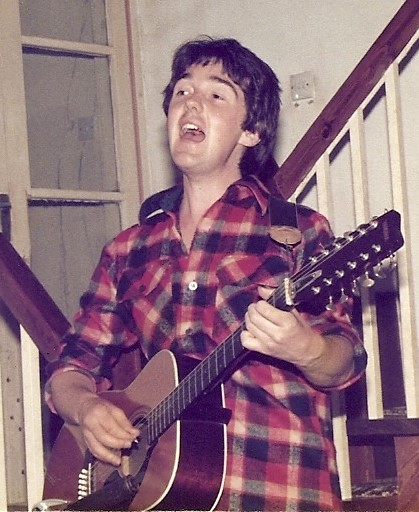

Keith Washington: During our last two years at school, Keith Ripley, Brian Teal and myself were part of a six-piece band called The Institute FUF, doing covers of all kinds of stuff, soul, R&B, Motown, The Byrds, Hendrix, Small Faces, The Who, and played pretty regularly in the local nightspots. Keith was the lead singer, Brian was on drums, and I had an electric 12-string guitar which was pretty unique at the time, but not particularly suitable for a lot of our material.

Philip McNally and Paul Simon were in another band who used to rehearse at the Arts Lab, so we got to know them quite well around that time, and then I think Paul and Keith Ripley were at art school together for a year after that.

At the time of ‘The Chemist’ recording I was living in London, and in a folk-rock band called Tintagel who were gigging regularly around London and South-East England and did a few radio broadcasts for the BBC.

Keith Ripley: I did join a group (and Brian followed soon after) in our mid-teens – The Institute. We were all in the same class at school. We played covers of songs we liked – Tamla Motown, Beach Boys, Byrds, Stax. For about two years we played pubs and clubs around the area, and stopped when we were approaching A-level time

Keith Ripley: There were three main places – Palings, the Jazz Club, and later Clarences. I saw a lot of people at the Jazz Club – Victor Brox, Wynder K. Frog, Root and Jenny Jackson, Long John Baldry. Next to the Jazz Club was The Upper George where we all met for years – it was the centre for what could be called the counterculture in Halifax. Later there was a club called Clarences, where I saw Terry Reid with David Lindley, Roxy Music, Arthur Brown, Ian Dury, Medicine Bow, etc. We also went to Leeds University and saw Traffic, Pink Floyd, and all sorts of people. For a while the Jazz Club became Halifax Arts Lab with characters like Jeff Nuttall hanging about.

What was the local music scene like back then? Were there particular places you enjoyed meeting up, discussing music, or perhaps hearing new material?

Keith Ripley: There were three main places – Palings, the Jazz Club, and later Clarence’s. I saw a lot of people at the Jazz Club – Victor Brox, Wynder K. Frog, Root & Jenny Jackson, and Long John Baldry. Next to the Jazz Club was The Upper George, where we all met for years; it was the centre for what could be called the counterculture in Hx. Later, there was a club called Clarence’s, where I saw Terry Reid with David Lindley, Roxy Music, Arthur Brown, Ian Dury, Medicine Bow, etc. We also went to Leeds University and saw Traffic, Pink Floyd, and all sorts of people. For a while, the Jazz Club became Halifax Arts Lab, with characters like Jeff Nuttall hanging about.

When did The Musical Players originally form? Who was in that first line-up, and what was the catalyst for starting the group? Was there a specific concept or philosophy behind it?

Keith Ripley: After finishing the group, we carried on playing music to each other. Then Washy made a record in 1970, and I thought I’d do one the year after with some of his stuff. Then it became, for a few years, a yearly event.

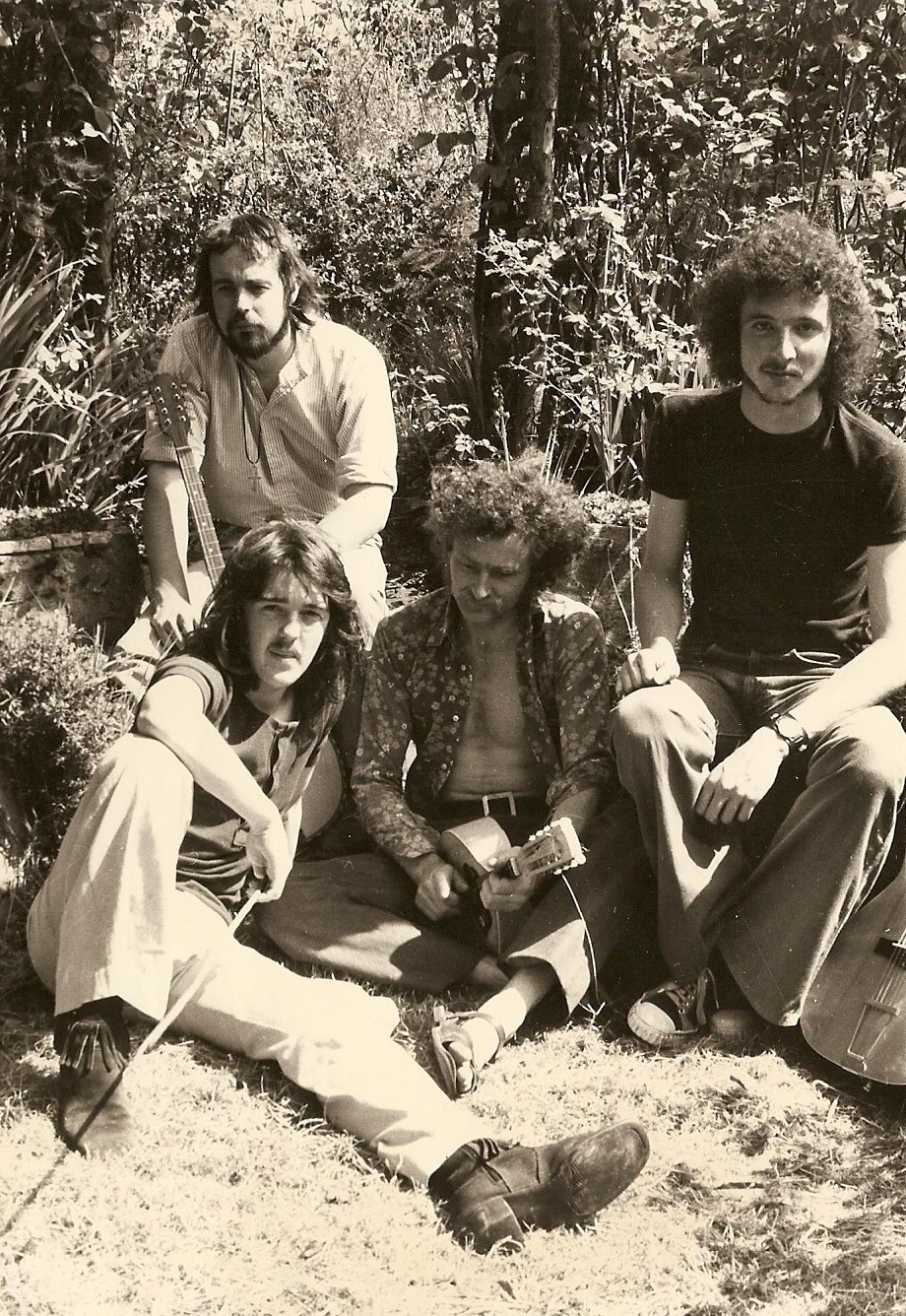

The Musical Players has been described as a “loose collection of musicians” centred around yourselves, Keith Ripley and Keith Washington. What was the central unifying force that held this collective together, if only for the span of this recording? How fluid was the line-up, and how did the inclusion of instruments like the sitar and violin come about—were these core members or itinerant collaborators drawn into the ‘woodland rites’?

Keith Washington: Essentially, The Musical Players were just a group of friends, with varying degrees of musical ability, who came together from time to time to jam and sometimes to record songs that Keith Ripley or myself, and later Brian Teal, had written. The name only really applied to The Chemist project, we didn’t use it for our other recordings, and we never performed as The Musical Players.

The musical nucleus of the band was really Keith Ripley and myself, plus Philip McNally on bass and one of two or three others on drums or percussion. The rest of the line-up was, to some extent, dependent on who was around at the time or, in the case of the string players, specialist ability. Everyone brought along whatever instruments they could muster and contributed what they could. The sitar belonged to Col Innes, and the studio provided the organ.

Keith Ripley: We knew people from school who played violin, so I tried my hand at writing parts. People were influenced by the Incredible String Band, so Col bought a sitar. I don’t think there was a unifying force as such. There was a core group, and then others who were also in bands in Halifax.

Could you tell us how your recordings resurfaced after so many years?

Keith Washington: Someone called Damon Jones bought a copy of ‘Beads of Rain’ last year from a market stall in Huddersfield, investigated the name Keith Ripley and found he lived nearby in Bristol. He knew Jon Groocock who runs Bright Carvings, and Jon contacted Keith and found out about our history. I think he intends to re-release some of the rest of our back catalogue in the future.

Keith Ripley: A man called Darren was in Huddersfield visiting friends—he was in the local market and bought Beads of Rain. He liked it and wondered what happened to the artist named on the cover. He was surprised to find that he lived in the same city, Bristol, so he thought he’d call on me. I was out playing Javanese gamelan and came home to find him in the front room talking to my partner. She asked me if I liked Darren’s record they were listening to, and did I recognize it. I was astonished that it was me—I hadn’t heard the record for 50 years!

The original pressing is a near-mythic artefact, supposedly limited to around ten copies. Could you walk us through the actual logistics of that initial run? Was this a deliberate choice to limit the distribution to a closed circle, and did you send any copies to radio stations?

Keith Washington: I don’t remember the exact details but the number of copies made was probably dictated by our limited budget and having no expectation that the record would be of interest outside our immediate circle.

Keith Ripley: The records we made back then were just for friends. I think Washy made about six copies of ‘Exodus’. As for the ones we made together—’Friendly’ and ‘The Chemist’—we probably produced about two dozen copies. I then made ‘Beads of Rain,’ which was composed entirely of my own songs; I had about 30 pressed and did try to sell those to acquaintances.

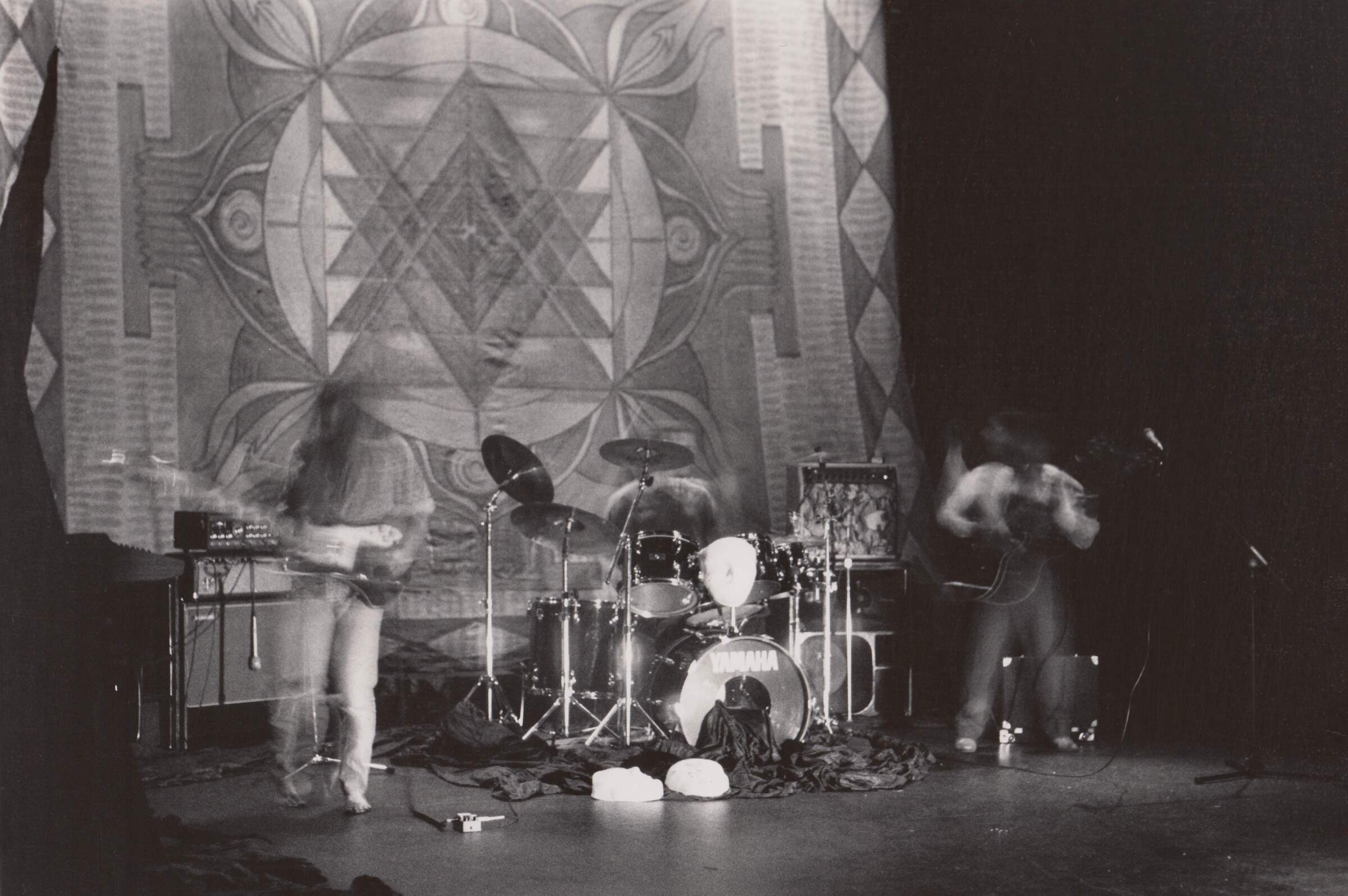

Did the band ever play any live gigs?

Keith Washington: The Musical Players only really existed as an entity for this one recording, though different combinations of the individual members, particularly Keith, Brian, Philip and myself, recorded and played live together at other times.

Keith Ripley: No, but we did get together in the ’90s and played one gig as a five-piece, playing electrically.

“Some of us did go through a period of evangelism about acid”

The album title explicitly references Leary (“The Preacher”) and Owsley Stanley (“The Chemist”). How did you view these figures? Are they simply symbolic signposts of the counter-culture, or was the album itself intended as a form of sermon or alchemical formula passed on to ‘The Musical Players’?

Keith Washington: We were aware of them and most of us at the time were or had recently been students so we were living the lifestyle to some degree. I can only speak for myself, but I don’t think we were consciously trying to proselytise through our music. I suppose something of your personal philosophy is bound to come out in your songwriting though. Phil Hartley came up with the idea for the album title and I think he was more evangelical about the acid culture.

Keith Ripley: It came from a friend of ours – Phil Hartley – I just thought it was a great title. Some of us did go through a period of evangelism about acid, but it only lasted a year or so.

You cite the Incredible String Band and Tyrannosaurus Rex as strong influences. Could you elaborate on how their work impacted yours? (Self-contained question made from the original statement/partial question.)

Keith Washington: This applies more to Keith Ripley than to me. I liked and had records of both of these bands, and I’d seen them play live too, but I don’t think they directly influenced my songwriting, apart from one earlier song I’d written which owed quite a bit to Tyrannosaurus Rex. I’d say Leonard Cohen and Joni Mitchell were probably more of an influence for me at that time, though I’ve always been eclectic in my musical taste.

On ‘The Chemist,’ I think you can hear some echoes of Tyrannosaurus Rex in our use of acoustic guitars and hand percussion, and of the Incredible String Band in the use of varied instrumentation, as well as in some of Keith’s songs and vocal delivery.

Keith Ripley: When I first heard the String Band, I was entranced—they sounded like nothing else I had heard. The subject of their songs, the delivery—it was like nothing else. I went to see them in Leeds and the stage was full of different instruments, which took a long time between songs to mic up. I saw them in Sheffield a couple of years later and they were a very tight group then. Williamson was very imaginative…a very charismatic character and I was heavily influenced by his songwriting.

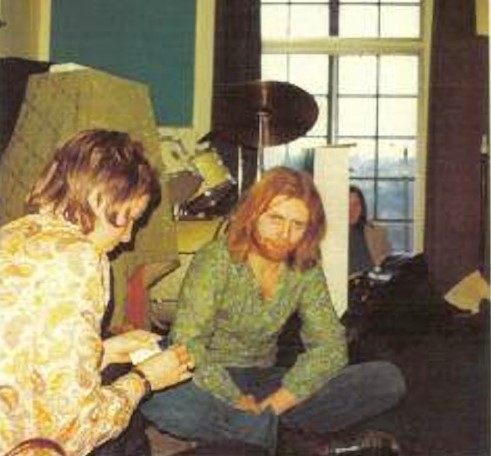

Could you share some further details about the recording and production process? Where exactly did you record the material, and how were the songs written?

Keith Washington: The recording was made at Northern Broadcast Recording Studio near Huddersfield, the next town to Halifax. It was run by a guy called David Whitely who was or had been a BBC sound engineer. We’d used the studio a couple of years before to record our album ‘Friendly’. For ‘Friendly,’ we’d done the whole thing in one session and realised we needed longer, so for this record we booked two sessions, April 1, 1972, 4pm to 11pm, and April 2, 2pm to 6pm. This at least allowed for more than one take of each song, but in effect it was a live recording.

I can’t remember too much about it but it was a fairly basic set-up I think. The main studio was in the upstairs living room and the control room was downstairs somewhere. As far as I know, it was only a two-track recording so they were mixing as they went along. I don’t remember there being much in the way of sound separation. What production there was came from the songwriters, Keith Ripley said what he wanted on his songs and I did the same for mine.

As I mentioned, I’d put music to a poem written by Keith Coleman and Keith Ripley did the same to something Meryl had written, but otherwise Keith and I wrote the songs separately and more or less on our own. We sent each other the words and chords beforehand but I don’t remember too much in the way of rehearsal, certainly not with the whole ensemble, so a lot of what you hear on the record was improvised in the studio.

Keith Ripley: It was recorded in a large house in Golcar, near Huddersfield, belonging to David Whitely, who worked for local television. We played on the ground floor, and in the basement he had the recording desk, etc. We had recorded ‘Friendly’ there the year before.

We would love it if you could add a few more comments or insights about the actual songs on the album.

Keith Washington: Only four of the eleven songs were mine. I’m not sure now why that was, maybe because they were a bit longer than Keith Ripley’s. The most recently written was ‘I Know How You Feel’. At the time I’d separated from my girlfriend, though she was present at the recording so we must have got together again by then, and I was living on my own in a bedsit in London, so I was feeling a degree of alienation but trying to be optimistic at the same time. Musically, I think it was influenced by David Bowie’s ‘Hunky Dory’ album, and specifically the song ‘Changes’.

‘New Kind of Life’ was an older song, about a break-up with a previous girlfriend, and one I used to sing with Tintagel, which is also true of ‘Adult Tree Ballad.’

‘By the Window’ was a song I’d written a couple of years before, expressing existential angst and looking to the healing powers of nature.

Keith Ripley: My songs were heavily influenced by a desire to be in nature—some of the titles came from names of hills—’Sails,’ and one from a flower—’Lady’s Slipper’. My parents had a caravan in the Yorkshire Dales and we used to go for weekends. We’d walk, explore, go down potholes. For a while I wanted to live up there in some village that had been started by the Scandinavians coming over from Ireland over 1,000 years ago—I loved that idea of history.

Could you outline the different line-ups and the years associated with the band’s activity?

Keith Ripley: People started drifting off to university, getting jobs, getting married, so it became harder and harder to do things in the same way.

I started making music again in the late ’90s, setting up a home studio through the influence of a friend of mine called Judy, and so made CDs of songs I had written and never recorded. Again, they were just given to friends. I also became involved in playing Javanese and then Balinese gamelan.

The last CD I recorded was entitled ‘Kolam’—it’s on Bandcamp.

Did you ever anticipate that your work would be re-released on vinyl nearly fifty years later?

Keith Washington: Absolutely not!

Keith Ripley: Not at all. I’m quite bewildered by it!

Were there other sessions, different line-ups, or even other albums that were conceived or partially recorded, only to be lost to the mist of time?

Keith Washington: During my first year living in London I did some folk club gigs and wrote a few songs. Then, in the summer of 1969, I booked a few hours in a studio in Hebden Bridge, Yorkshire, and recorded a five-song EP called ‘Exodus’ with the backing of Col and Brian on percussion. Keith wasn’t able to attend the session but he did the front cover image.

The following summer, we did the first of our joint recordings, the album ‘Friendly,’ which we did at Northern Broadcast in Huddersfield. The personnel was much the same as for ‘The Chemist,’ minus the rhythm section of Paul and Philip and with just Janet playing violin.

After ‘The Chemist,’ we made a couple of albums at another local studio run by John Verity who had his own band and later was the guitarist in Argent. The first of these was ‘Beads of Rain,’ which was an album of Keith Ripley’s songs except for one Dylan cover, but the line-up was very much the same Musical Players core personnel with the addition of Robert Simon, Paul’s brother, on some tracks.

The second, later named ‘After All,’ was a combination of songs from Keith and myself, plus three from Brian Teal, with a similar line-up. Unfortunately, there was a problem with the master tape so ultimately this was not committed to vinyl at the time, though CD copies exist.

After this we went our separate ways for a while, though both Keith and I have done recordings with Brian and Mac at different times. Keith, Brian and I did a few gigs with a couple of other guys as The Holroyd Brothers in the nineties.

Keith Ripley: The year after ‘Beads of Rain,’ Brian, Washy and I did some recordings at John Verity’s studio in Queensbury near Bradford, but they never got on to vinyl.

What currently occupies your life?

Keith Washington: After retiring from a career in education, mainly teaching performing arts, I built up a studio at home and, besides doing some mixing and production work for other songwriting colleagues, I’ve recorded a number of albums of my own songs under my artist name of Albert Promenade. Also, I play regularly with a ukulele band and have done occasional performances with a group of other songwriters locally.

Keith Ripley: Well, last year I had a heart attack, and this year in September I had an operation to remove a cancer in my oesophagus, so I’m concentrating now on recuperation!

I have some songs that I hope to finish in the following months—one of them a song about my grandad who, after the end of the First World War, signed on for a few more years, marched into Jerusalem with Allenby, and ended up in Egypt guarding Turkish prisoners of war!

Klemen Breznikar

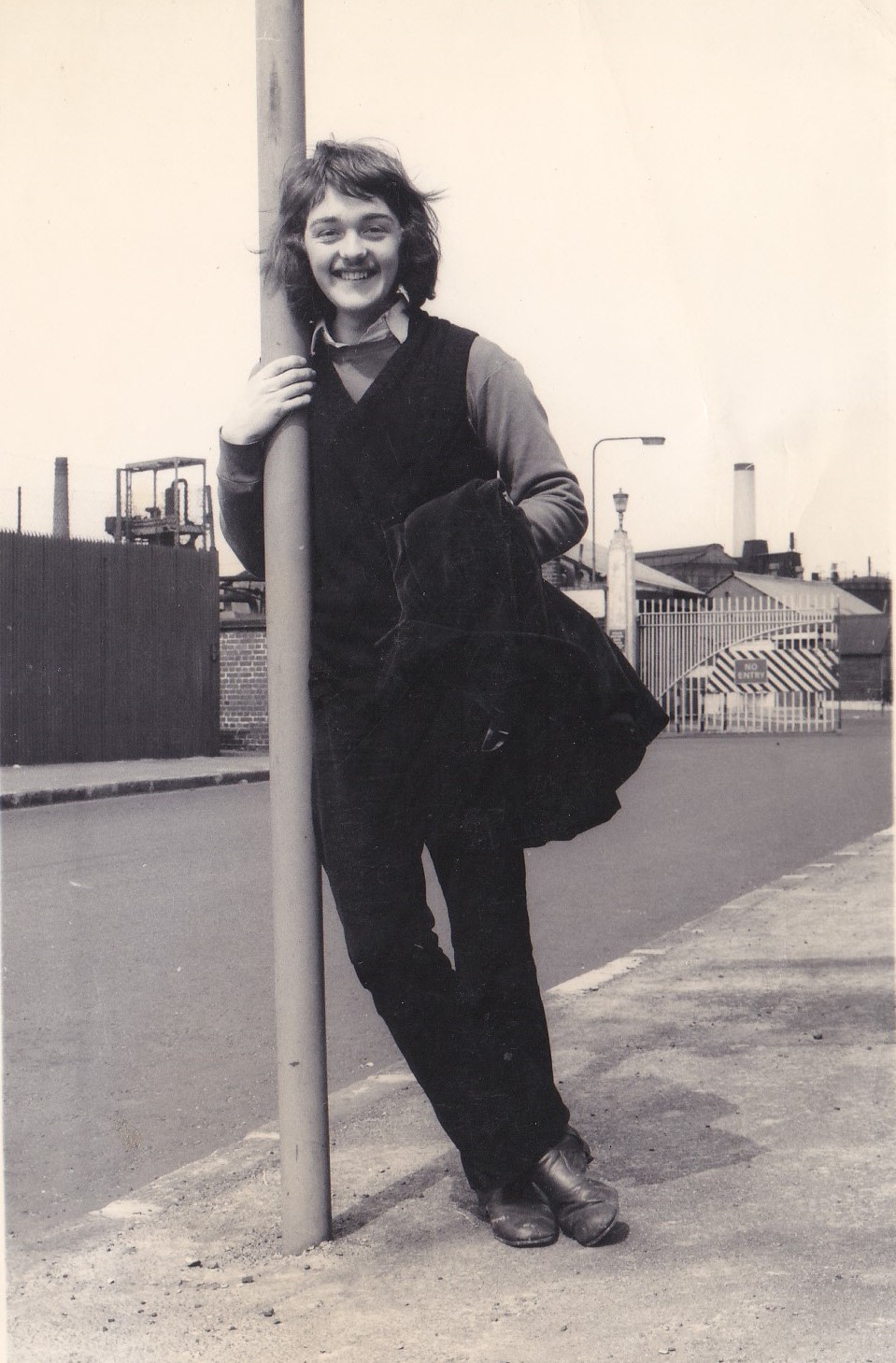

Headline photo: The Musical Players

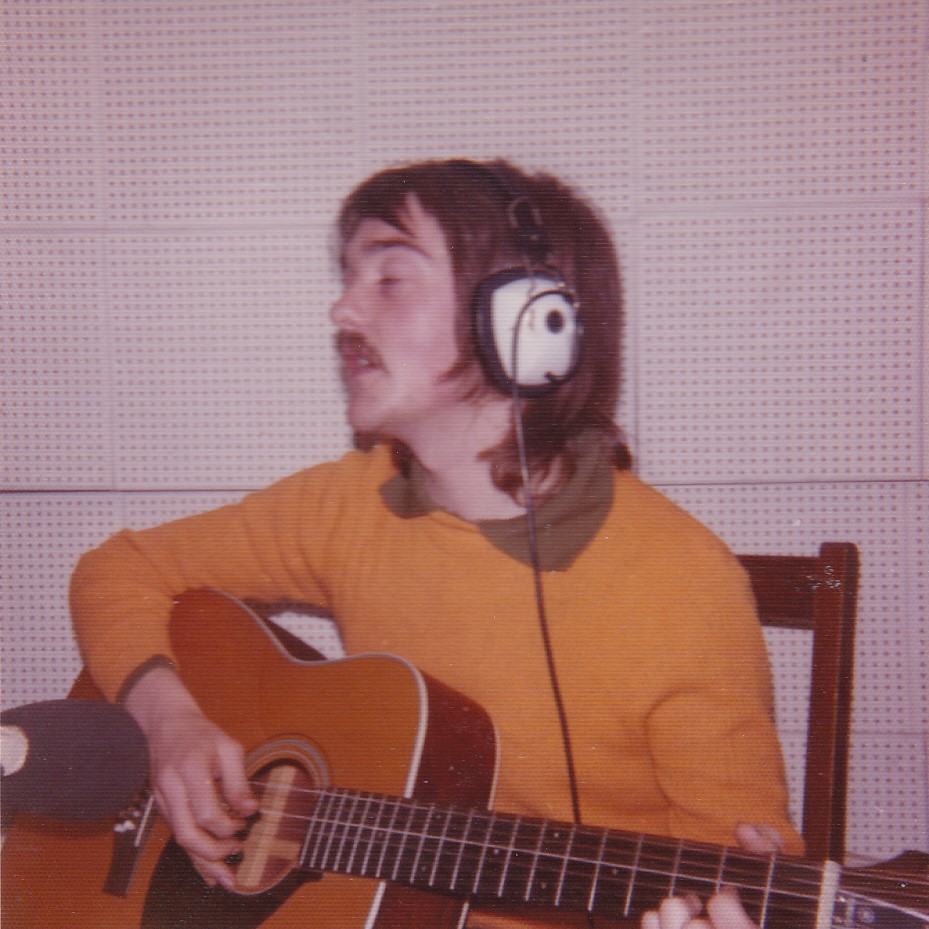

(All photos: Keith Washington and Keith Ripley private collection)

Bright Carvings Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / YouTube