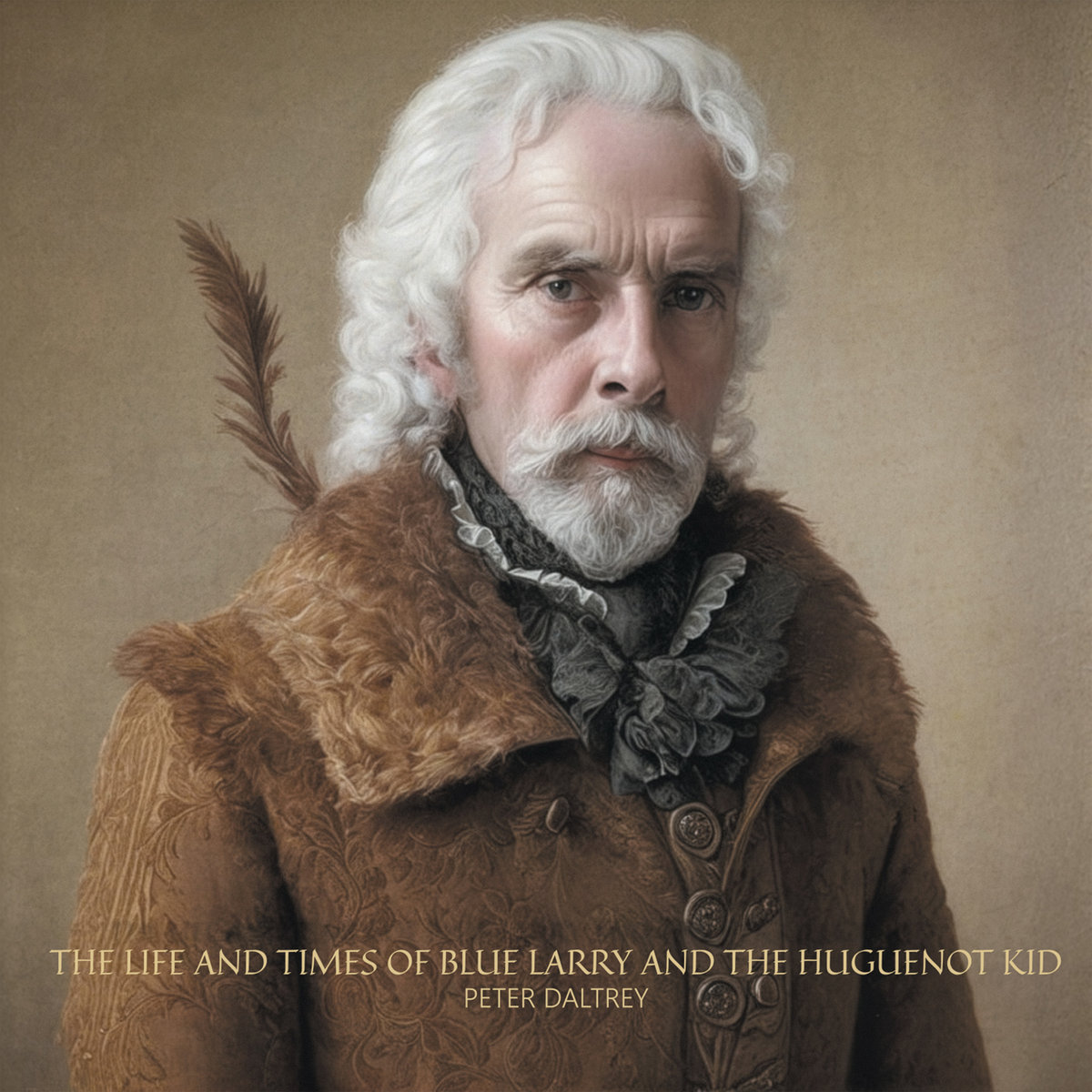

Peter Daltrey on ‘The Life and Times of Blue Larry and the Huguenot Kid’: From Kaleidoscope to Fairfield Parlour

For anyone who has spent time digging into the deeper seams of British psychedelia, Peter Daltrey needs little introduction. As the singer, lyricist, and conceptual centre of Kaleidoscope, he helped create some of the most distinctive and quietly disturbing records of the late 1960s.

Albums like ‘Tangerine Dream’ and ‘Faintly Blowing’ stood apart from the era’s more flamboyant psych gestures, replacing technicolour excess with narrative songs full of shadow, domestic unease, and half-glimpsed myth. Kaleidoscope’s brief lifespan and small catalogue only sharpened their reputation, later cemented when the band re-emerged as Fairfield Parlour and carried those ideas into more pastoral, progressive territory.

What often gets lost in that story is that Peter Daltrey never stopped moving forward. Across decades of solo work, he has continued writing character-driven songs that blur memory, history, and invention, largely outside the glare of attention. His latest release, ‘The Life and Times of Blue Larry and the Huguenot Kid,’ issued by Think Like A Key Music, is very much the latest chapter in a long, uninterrupted line of thought.

The album is framed as a song cycle connecting two unlikely figures: an 18th-century Huguenot craftsman fleeing religious persecution, and Blue Larry, a grotesque, contemporary Los Angeles hustler orbiting money, vice, and an overbearing maternal bond. Daltrey resists easy parallels. Instead, the record allows the two lives to exist side by side, connected by mood, voice, and an underlying fascination with displacement and inheritance.

Musically, the album favours restraint and clarity. The arrangements are warm and intimate, closer to chamber psych-folk… All in all ‘The Life and Times of Blue Larry and the Huguenot Kid’ confirms Daltrey as what he has always been: a songwriter committed to story, atmosphere, and the slow accumulation of meaning.

You can order your copy of ‘The Life And Times Of Blue Larry And The Huguenot Kid’ by Peter Daltrey directly from TLAK’s website.

“I used shadows to emphasise the light.”

Okay, Peter, let’s talk about the collision at the heart of the new record. You’ve got Blue Larry, the corpulent hustler, pure L.A. sprawl and mother issues, versus the Huguenot Kid, an 18th-century French craftsman running from the fire. This ain’t your usual “concept album” structure, it’s more like a psychic cross-stitch across time. When you finished the last track, what was the definitive, non-negotiable truth these two found in their entanglement? Was it a modern parable about the futility of running, or did the past guy actually have a lesson for the poor, ill-gotten soul in the now? Is this album your way of telling us that the same old human dirt just changes its clothes every few hundred years?

Peter Daltrey: I guess if you look closely enough you might find threads, wires and twists of unrelated DNA that link our two orphan peas in a historical pod. I’m a songwriter and if you slice me in half like a stick of Coney Island rock you might find the word “storyteller” printed in every cell and old bone. There is no great plan here, no scientific formula that goes from logarithm to logic and out pops an answer that can be ticked conveniently.

Whilst it would be easy to smear the dirt on Blue Larry with his penchant for college girls, easy money, magic dust, fat Havana cigars and dancing with his mum, it might be hard to dirty the name of my Huguenot ancestor, and Catherine, his missus. And if you did you’d find me on your doorstep with a neatly typed lawsuit before you could say, “I love Jimmy Daltrey…!”

I do doubt that Larry would offer our Huguenot hero a toke on his bowl, but he might also ask after the health of his mother, left behind in hostile France, grieving for her best boy. Much like James might console big Blue Larry upon hearing that his frail mother can no longer jive or twist or jitterbug or whatever uncivilised dance she used to do. Perhaps they are just two lost boys, James traversing the troubled waters of the turbulent English Channel in search of new roots, and Larry rooted in the underbelly of L.A., but footloose and fancy-free and soon to be tragically uprooted by the timely death of his skin-and-bone matriarch. Poor Larry.

Your career, even solo, is often viewed through the Kaleidoscope lens. Yet ‘The Life and Times’ feels incredibly warm, earthy, and character-driven. It’s more Robert Wyatt’s melancholic chamber-pop than British psych fantasia. This is your 28th solo album. Was making a record that relies this heavily on wit and intimate arrangement a deliberate move to push back against that enduring ’60s tag, or is this simply the sound the story of Larry and the Kid demanded?

It is heart-warming and frustrating in equal measure to be remembered for a band that was active for so few years but who managed to make a mere handful of albums that are so well respected, but then to know that those valued fans of that fleeting genre know virtually nothing of my later flowering. I’m the same guy who co-wrote all that stuff. If there was any magic in that, and you’d be wise to consider the fact that Ed, Dan and Steve were also equal partners in the outcome of that electric enterprise, then I hope it has not faded, but lurks deep in the pulsing neurons of my ageing frontal and parietal lobes inside my old noggin.

I was for years joined to Ed at the musical hip but when the band broke up I was all at sea. Well, not quite. I was a landlubber, thatching a derelict cottage in the wilds of Wiltshire. But the muse followed me from Acton. I was soon writing again and by necessity was also composing. Flash forward a few decades and here I am with a back catalogue that will be a mystery to many. Ah, stop thy complaining, I hear a heckler cry. Far from it. I am working hard to get that word out. And with each album I inch forward, bringing Kaleidoscope and Fairfield Parlour fans with me on the final stages of this journey called “life, love and mystery and much staring at the stars in wonder…”

So no push-back against my fairytale-filled past. Far from it. So many of my own songs would sit very happily sharing a fag with Lewis Tollani or consoling Annie down the pub. Indeed, the Huguenot ditty and ‘English Roses’ would love to rub shoulders with that drummer boy from Shiloh.

Your lyrics have always found turning everyday streets and moments into mythical, for example ‘Chelsea,’ the subject of a previous album. Larry and the Kid exist at two extremes. What specific, almost throwaway details did you seize on to ground those vastly different epochs and geographies? And more importantly, is there a single London-centric ghost, a figure or a place, that secretly haunts the tracks of this L.A./French fable?

Can we draw a line from the St Bartholomew Day massacre of Protestants in France in 1572 to the slaughter of the innocents at 10050 Cielo Drive in Beverly Hills at the fag end of the Sixties? I think not. The word refugee comes from the 1700s and was first used to describe the escaping Huguenots. Was Blue Larry escaping anything? I think not. James and Catherine were bound by love. Was Larry bound by a love of his doting mother? Certainly, but it was a claustrophobic love, a maternal connection that eventually turned obsessive and destructive.

Unless you are particularly perceptive you will struggle to find a “hands across the oceans of time” link between these two men, other than their creation by a man who has Huguenot blood coursing through his old cardiovascular system and who once recorded an album in a studio overlooked by the iconic Hollywood sign.

For a London haunting look no further than Spitalfields, the heart of Huguenot London and just two miles from where I was born. The Huguenot houses survived. Mine was made of asbestos sheeting, thrown together on a WWII bomb site and eventually torn down, put in the back of a lorry and driven away. Larry first lived in 4th Street in Downtown L.A., but through hard graft moved up the social ladder, never reaching a respectable rung, but wealthy enough to buy a used Cadillac with a leaky sump.

Larry and James were go-getter city dwellers. Larry, with a cheap movie camera and a skill for manipulation. James, a craftsman, a highly skilled fan maker who passed on his talent through many generations, all leading lights in the Worshipful Order of Fanmakers. In fact my grandfather and his father were still bone workers at the turn of the 19th century. Bone and ivory were used to make the arms of fans. These are threads of identity that should never be broken. I don’t think Larry even knew who his father was. Poor Larry.

The CD is the “Complete Chronicles”, all 13 tracks. The vinyl, however, is a distilled six-track selection, “Fragments & Fables”. What is the fundamental difference in the listening experience between the complete 13-track journey and the more compressed, vivid six-track vinyl version?

Audio quality for vinyl demands a running time of no more than twenty minutes per side. Vinyl lovers understand this and accept it readily, hungry for that listening experience that compels you to sit and listen as the needle traverses the hills and valleys of silky grooves. The CD experience is different, but can be just as rewarding. Do people still put a CD in a drive then sit and listen end to end? I should damn well hope so.

Creating an album track list is a task of joy. I try to create a mood that changes, swells and falls, flows and ebbs as each track ends and the next begins. Back in the day we bought albums and always did the sit-and-listen routine. No one in my house would put an album on, place the needle down and then start reading the local rag or popping in the kitchen to make a cuppa and grab a digestive.

‘Flight from Ashiya’ is a flawless piece of psych pop. But the thing about Kaleidoscope isn’t just the specific sounds or the whimsy. It’s the fact that songs like ‘The Murder of Lewis Tollani’ and ‘(Further Reflections) In the Room of Percussion’ hint at things dangerous, dark and utterly claustrophobic. Was the whimsy, the beautiful, dreamlike sound actually a necessary psychological counterweight for the band, a way to package and make palatable the deeper, more unsettling things you and Ed Pumer were observing and feeling in those late Sixties London streets?

Who knows where these stories came from or why many embraced a darker area as the day dimmed and we stuck our youthful heads through third floor windows to listen in awe at midnight’s broken toll? I wrote them and don’t know myself the attraction of tragedy. But all good stories can’t be all good news. I used shadows to emphasise the light. You can’t have a fairy tale that is peopled solely by fairies. Where’s the fun in that? I don’t like to spell out the sinister or weigh in with heavy drama. I prefer the hint, the suggestion, painting with shadows.

The band were happy with all this and it must have had an effect on the musical arrangements, the heart-beat thump of a bass drum, the plaintive cry of a flute, the agony of a guitar pushed to extremes of discordant, ear-damaging white noise. And anyway, what was psychedelia? Can it be defined musically? Is ‘Please Excuse My Face’ psychedelic? Certainly not, sir. And ‘Black Fjord,’ that tale of Viking pillage? Is psychedelia in the lyrics or the music or the melding of both? I guess so. We were fortunate to be plying our trade during that very short-lived vivid period. That is why you are asking me these questions almost sixty years later.

You guys changed your name to Fairfield Parlour, giving up what was probably one of the most perfect psych band names ever, and critics have always said that was a mistake. But the music you made after that, like ‘From Home to Home,’ had this more melancholic, progressive folk-rock feel. At a time when a lot of bands were still doing the sitar thing, you moved on. Do you remember the moment you felt that shift, when you looked at the name Kaleidoscope and thought, “No, that doesn’t fit anymore”? Was it a sense of creative freedom, or did it feel more like a weight professionally?

I blame our lack of commercial success as Kaleidoscope squarely on the corporate shoulders of Fontana. The lousy distribution, the lack of quality, well-planned promotion, but also the fact that Dick Leahy, our producer, and his publisher comrade Dave Carey at Flamingo Music, led us like sheep into the lion’s den of big label manipulations.

Both should have advised us from day one, literally, that we must engage a manager to represent us in all dealings with the label. Like so many bands before and after, we got screwed because we couldn’t be arsed to read the small print on the piece of paper we signed, effectively giving the label ownership of our recordings in perpetuity. Now that’s forever, kids. Once the bullying began, as the expected hit singles failed to appear and we were told we had to record songs by hack Tin Pan Alley writers, we knew our relationship with Fontana was over.

Our saviour came in the form of a big, avuncular, enthusiastic BBC disc jockey who was unfulfilled in his daily record spinning. He advised us to leave Fontana, change our name and start again. It was our lifeline. We embraced David Symonds’ ideas with creative relish, incorporating new instruments in our line-up which led to new, more ambitious arrangements for new songs.

We spent a summer at Dave’s gaff, just a five-minute knight-on-horseback ride from Hampton Court. Days mucking around like kids in the stream at the end of the garden, balmy evenings with the Moody Blues and Tymon, now monikered as Tymon Dogg, exchanging ideas and playing songs.

When we were armed with new songs we went to the studio. We recalled some songs from the Kaleidoscope years like ‘In My Box’ and ‘I Remember Sunnyside Circus’ and decided to include them on the first Fairfield Parlour album. Creative freedom it certainly was.

You’ve said you used to write the lyrics first, before Eddy Pumer even touched the music. That’s a fundamentally different approach from the jamming-to-find-a-hook method of many bands. When you presented Eddy with something as lyrically dense and vivid as, say, ‘A Dream for Julie,’ was there ever a push-and-pull struggle where the music fought to simplify or de-tangle your words, or did the clarity of your lyrical vision always force the musical structure into its perfect shape? Put simply, did your poetry dictate the music, or was it a gentle suggestion?

Ed used his musical intuition when it came to creating melodies for my scrawled lyrics, half of which were probably not much more than juvenile ramblings of a purple hue. I don’t recall ever disliking anything Ed played me in his high bedroom when both of us swayed on the boat of drunkenness after downing a bottle of the cheapest red wine we could find.

The system worked perfectly as we never went in the studio with unfinished songs or no songs at all. Time was of the essence. Although Dick Leahy almost had an open door to the vast Fontana studio, even he had to account for his time. We would already have sat in his office and played him these songs prior to the studio being booked. It was a fool-proof system until the record was released and the Fontana staff failed to fulfil their side of the bargain. What were they thinking after Dick had roamed from Chelsea to Camden telling anyone who would listen that he had just signed the new Beatles? Fact.

I should point out that the lyrics for our new dear friend, ‘Blue Larry,’ were written back in the early Seventies. The song flew under Ed’s radar and as far as I know he never worked on it. But a few months ago I came across it while daring to search boxes in our once rat-infested loft. I was struck by the storyline and decided to work on the song myself.

It was an epic task as the track clocked in at over thirteen minutes long, but I felt this was justified to give Larry his fair share of vinyl and CD airtime. He was a big guy with big dreams, big dramas and big cigars. He almost barged his way into the project. I have a life-sized mural of the band on my studio wall and Ed was watchful and critical throughout the long hours of arranging and recording. I’d like to think that Ed and Larry are pleased with the result.

Another thread that always leads me back. Do songs possess DNA? I have no idea how far I can look into the future. Not far, methinks. But going back, there is a whole country back there with friends and happenings both good and bad that forever draw me back to explore those blue, distant, singing hills.

When you finished recording ‘Tangerine Dream’ in 1967, and put the needle down on the final mix, did you and the band have even a shred of an inkling that you had just created a record that would become a perennial benchmark for psych rock? Did it feel like a masterpiece of the moment, or just another set of fully formed songs that somehow failed to catch the fickle chart-eye? Was the true reward the sound of that first playback, before the public misjudgement had a chance to weigh in?

Certainly the first play-through of any album is a visceral experience. You are suddenly made aware of the result of all those hours of work, from the first scratchings of a biro to the strumming of Ed’s guitar, from the first time I heard the song to the first time we played it to Dan and Steve, from the hours in the studio to the waking night of anticipation. It all adds up to that album.

There was one occasion when a first play-through left me close to tears. As well as managing us, David Symonds also produced our Fairfield Parlour material. When he had finished mixing ‘From Home to Home’ he told us to meet him at Olympic Studios in Barnes for a first listen. We assembled and sat in the comfy chairs facing the state-of-the-art speakers. Dave would never play music at less than eleven, ear-shredding and wonderful.

The album was breath-taking in its scope, musical depth and true to its pastoral roots. But one track literally left me speechless. ‘Emily Brought Confetti’ was ambitious, from its lush arrangement to its bank of choral movements. We were driven back into our seats by its magnificence and its wide-screen stereo field. The four of us stumbled from the studio into the falling night. We all looked at each other and were naively convinced we had just made a great record that was going to break us, with the success we craved just weeks away. No. It didn’t happen.

I love that album and if I ever listen to it again I will wreck my ears once more by playing ‘Emily’ at eleven and closing my eyes before emerging spellbound into a rural night, hoping for glimpses of the necklace of lights that turn Hammersmith Bridge into Barnes’ very own Milky Way.

The odd thing is once I’ve listened to a new album I very rarely listen to it again. There is always more work to do. It would seem self-indulgent to listen to my own records. I also have to be careful not to add further damage to my hearing. Without that I won’t be able to work. Come to think of it, I never listen to music, even my favourite songs of Dylan or Cohen or whoever. I must keep working. Keep on carving.

“I am still, after sixty years, in awe of the process.”

When you were making ‘The Life and Times,’ which is such an ambitious and complex record, did you feel like you were consciously refining your songwriting? Does the satisfaction now come less from that sense of discovery and more from nailing a well-formed vision, kind of the opposite of the spontaneous energy of the Kaleidoscope days?

It’s not from a sense of discovery or at finishing a song. It is the initial wonder, the magic that is needed to compose a song in the first place. I am still, after sixty years, in awe of the process. I can wake up with nothing in my head and an average day ahead when, without warning, a line will come to me from nowhere, or after reading a headline or a sentence in a book, and there is a mental spark.

Within just a few minutes or an hour I will have written a lyric and if I have access to my keyboard I will have worked out a chord sequence. Then the dreaming begins, listening to the song in my head, arranging the silent instruments, hearing it all. After that it is a matter of hard work, bringing all those thoughts into focus, experimenting with instruments, constructing the format of the song, what goes where. Once all that is done I lay down many vocal takes, lead and harmony, until I have enough to put together a rough mix. I’m in charge. I like that. I only have to answer to myself. There is always a quiet but insistent voice I hear that adds advice and constructive criticism. I think it must be Ed.

Do you view this project as a critique of how American mythology, particularly the pursuit of illicit gains and self-reinvention, represents a perversion or ultimate fulfilment of the older European impulse for freedom and sanctuary?

Nope. It’s a collection of the best songs I can write. No politics reared their ugly, destructive heads in the making of this record.

In contemporary culture, the anti-hero is a dominant archetype. Larry, the “corpulent hustler with mother issues”, certainly fits a modern dramatic template. The Huguenot Kid, fleeing persecution, embodies an older, more classical strain of suffering. Does the entwining of their tales propose a new kind of moral compass for the 21st century?

A moral compass? Wow. That’s high and mighty stuff. Larry and James bracket this collection of songs. Their life stories exist in different spheres of human endeavours. Cheese and chalk perhaps, but stories of life nonetheless.

I’d like to think that at some time, working hard in his house in Spitalfields, James Daltrey might have looked up for a moment, gazed from his window at the London skyline and had a daydream about me, about the future. What might his ancestors think of him? Would his brief time resonate with another who bore his name, my own middle name? Would the family tree still flourish in a hundred or three hundred years’ time? And then after that oaken moment he would continue carving his piece of bone.

As for Blue Larry, I don’t think he thought further than the next deal, the next hit, or if his mother had taken her midday medicine with a slug of Bourbon.

I don’t live by a compass, moral or otherwise. I think I am driven by DNA. Perhaps I am a bone worker after all. My songs are my bones.

Klemen Breznikar

Think Like A Key Music Official Website / Facebook / X / Instagram / Bandcamp / YouTube

Kaleidoscope & Fairfield Parlour interview with Peter Daltrey

Peter Daltrey & The Know Escape | Interview | New Album, ‘Running Through Chelsea’